Islam has given me a moral foundation, a way of trying to balance your own personal ambitions, what you want and need in the world, with some type of morality... There are so many problems in the Islamic world. I think those have to do with politics and the Islamic world's reaction to colonialism.

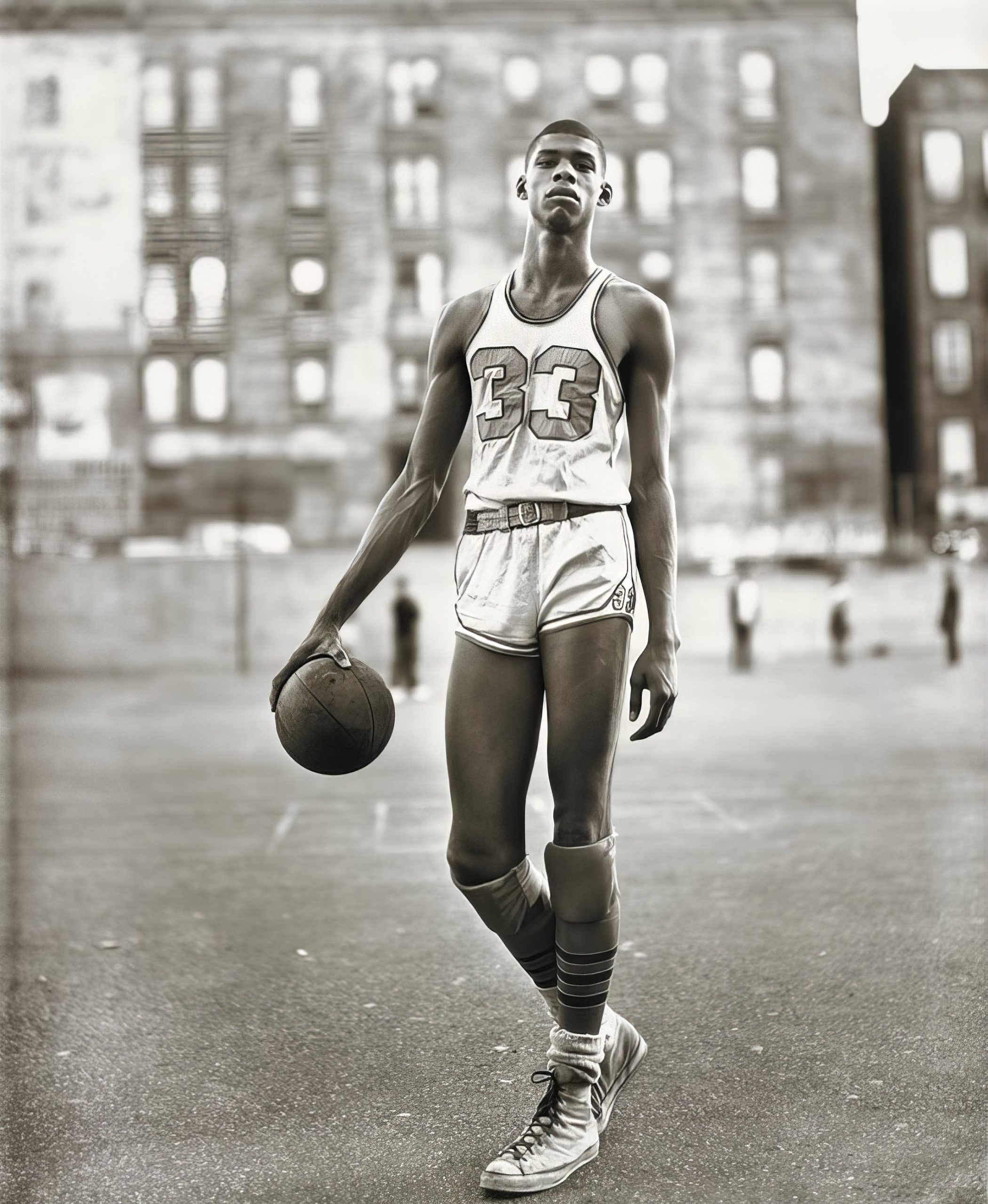

The legendary athlete known today as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was born Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor, Jr. in New York City, the only child of Cora and Ferdinand Alcindor. The young Lew Alcindor, as he was called, was an enthusiastic athlete. He grew quickly, and throughout his school years was the tallest child in the school system.

It was natural that his teachers and coaches would steer him towards basketball. He did not take to the game immediately, but with patient application, he mastered the essentials, and as early as the fifth grade was developing the soaring “sky hook” that would become his signature shot on the basketball court. His parents were adamant that he pay attention to his studies as well. He was their only child, and they were determined that he prepare himself for college. His prowess on the basketball court won him a scholarship to Power Memorial, a private Catholic high school.

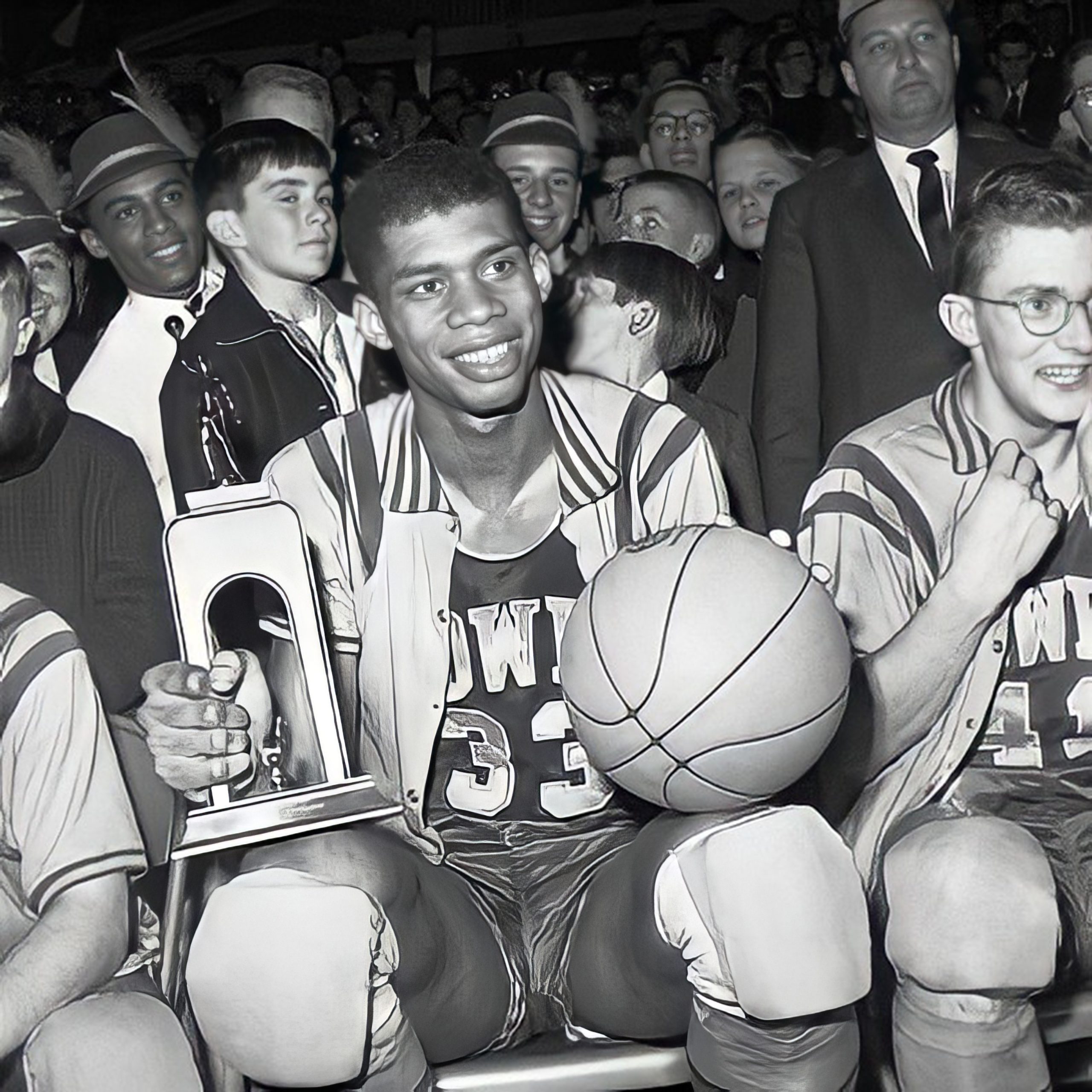

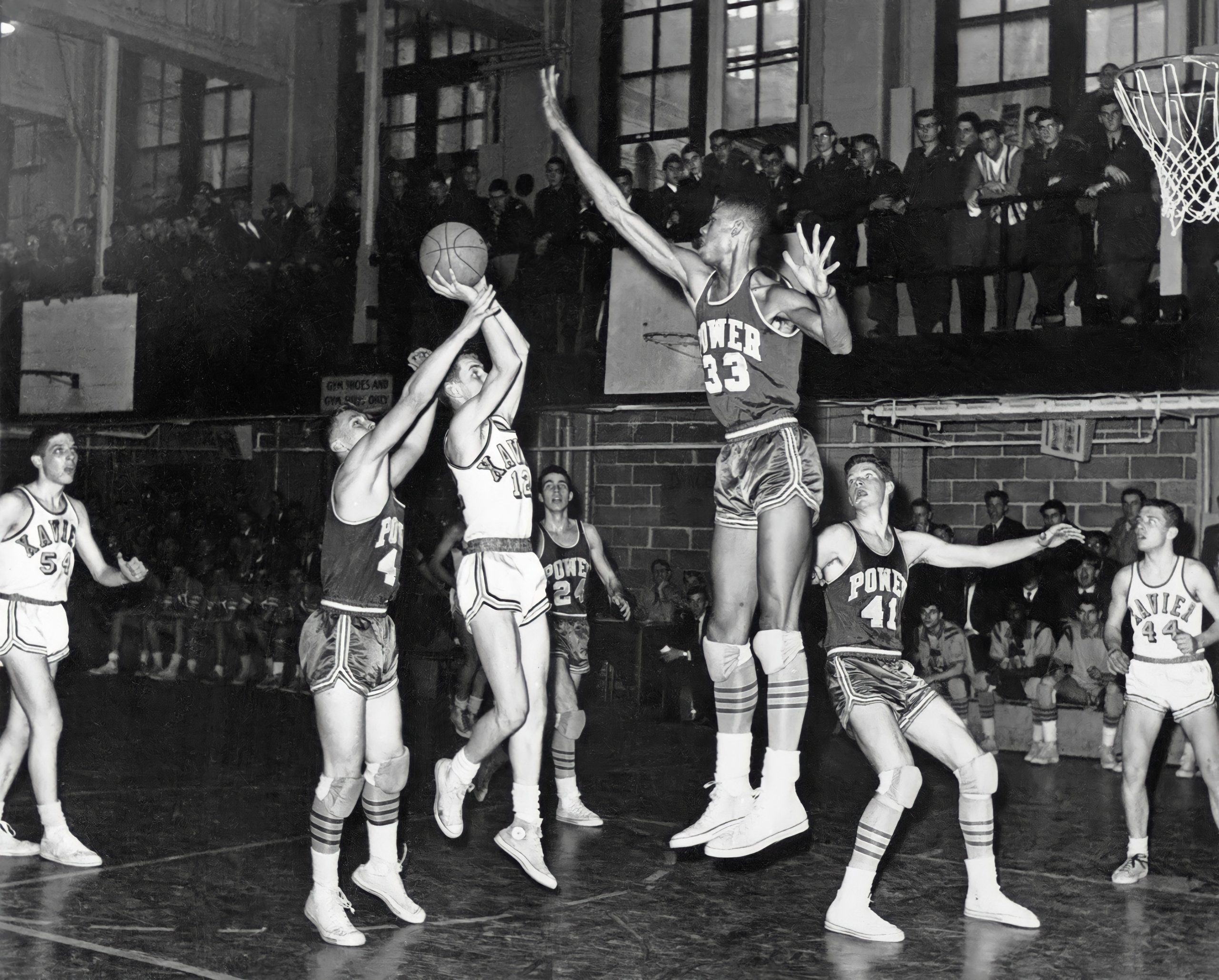

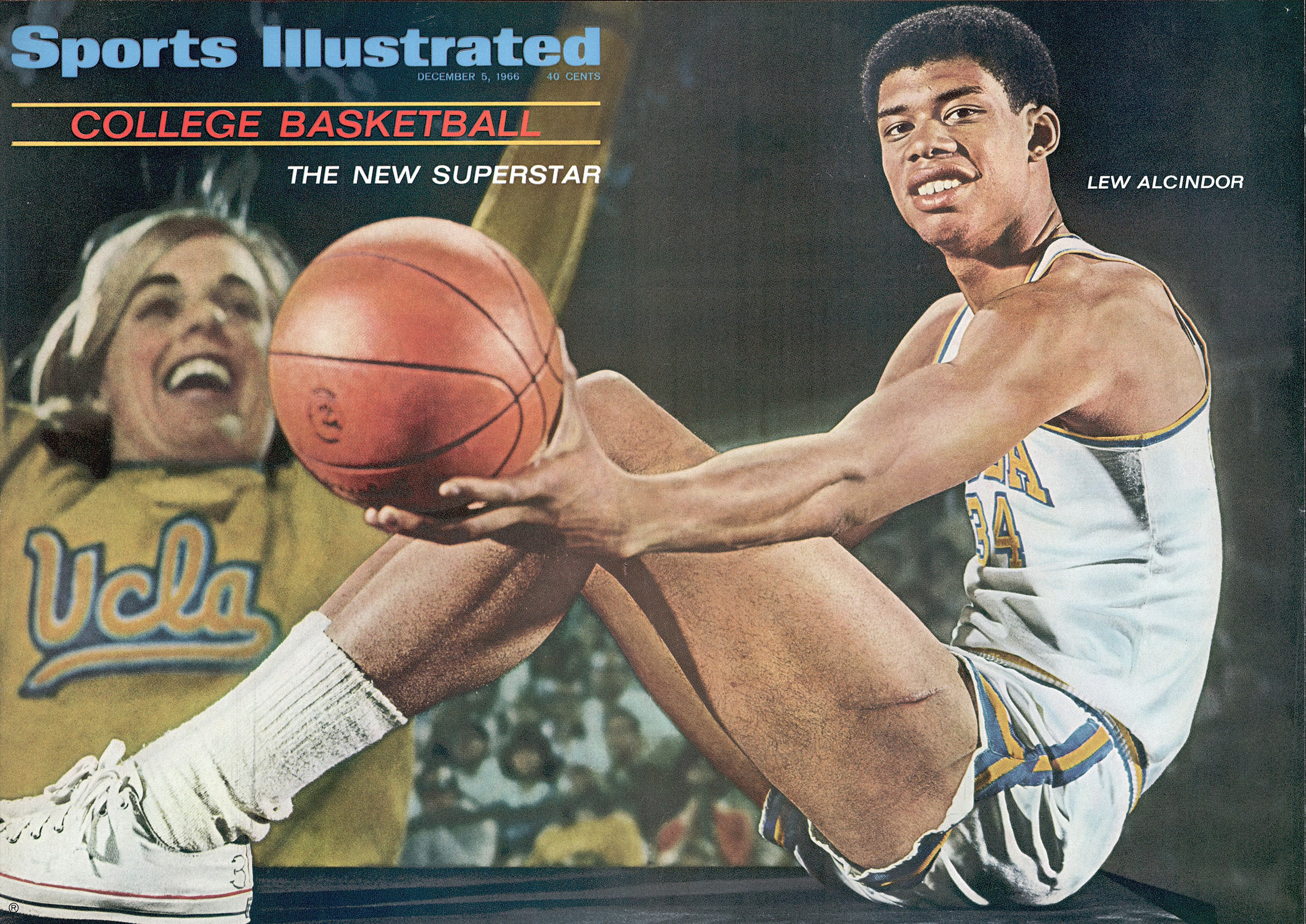

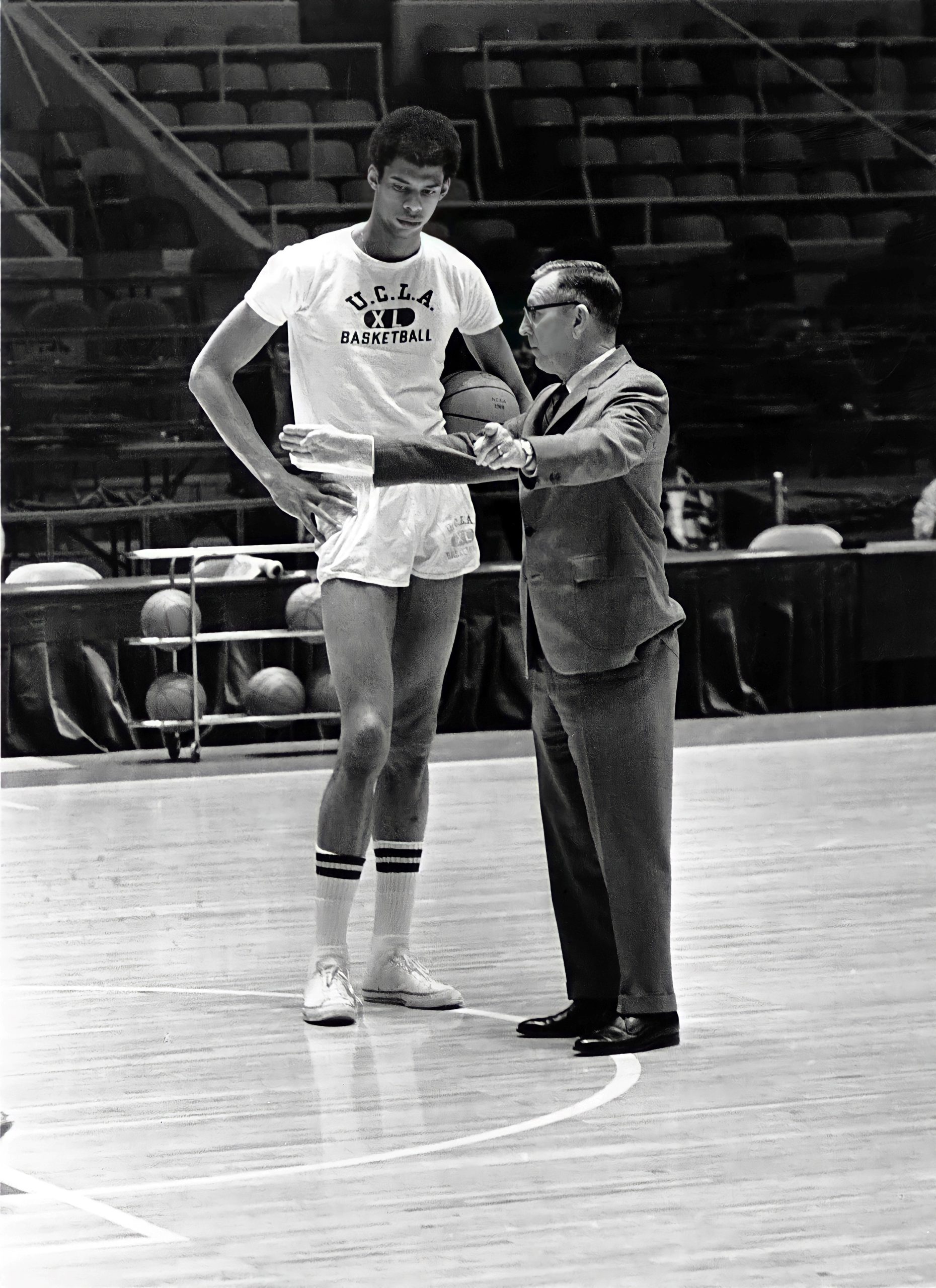

The national sports press first took note of Lew Alcindor when he was only 15, playing for Power Memorial. He led his school team to 95 victories in 101 games and three consecutive championships in New York City’s Catholic school league. In all three years, he was named a High School All-American. The top college basketball teams were all eager to recruit the young phenomenon, but he soon chose the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), where he could work with fabled coach John Wooden. Coach Wooden had led his team to two previous championships, but with the young Lew Alcindor as center, the UCLA Bruins were about to embark on an unprecedented winning streak.

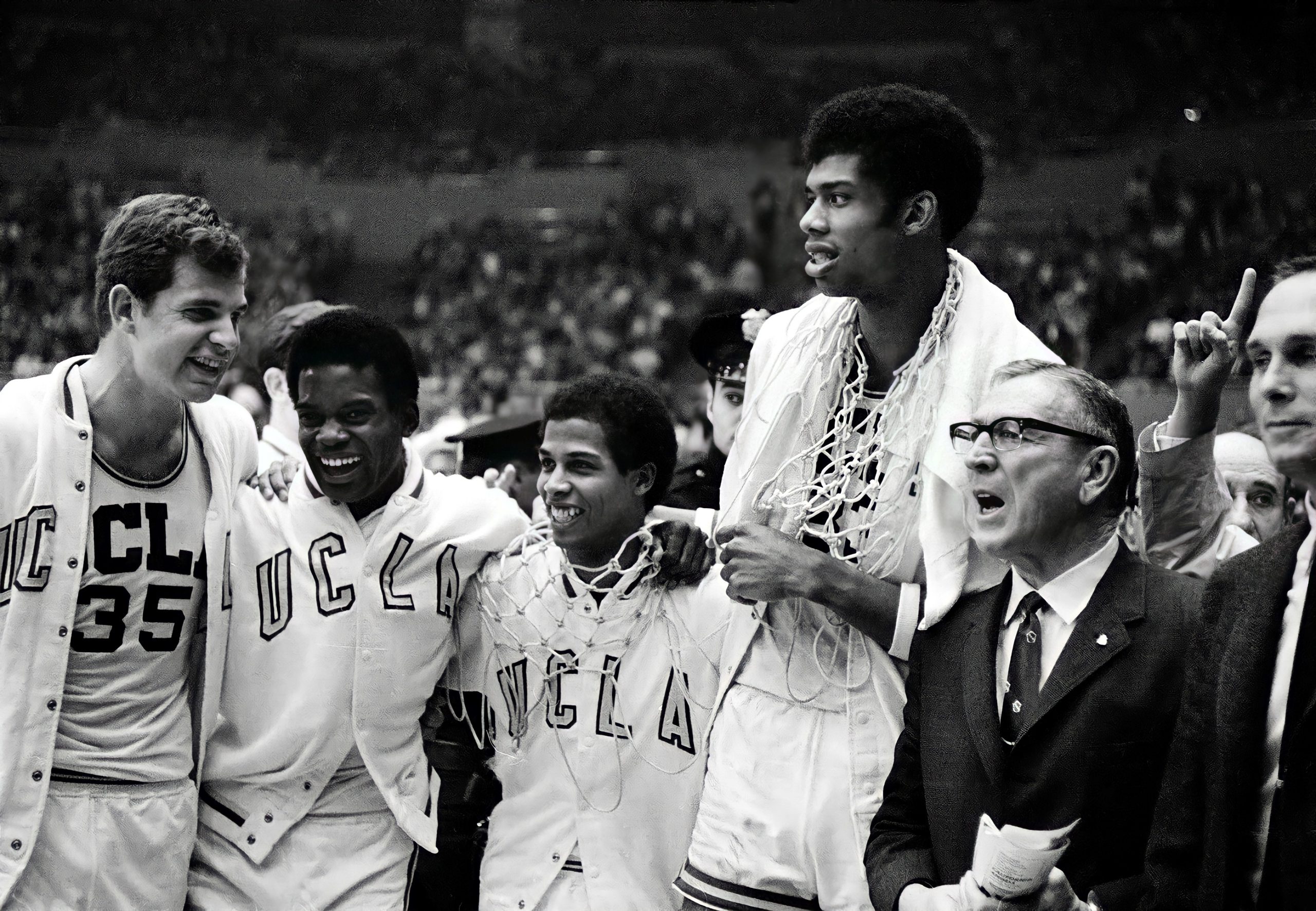

At the time, National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) rules prohibited freshmen from participating in varsity collegiate play, but when Alcindor became eligible in his sophomore year, he immediately dominated the college game. The Bruins were national champions all three years (1967-69), losing only two games out of 90. To date, he is the only athlete to be named the NCAA Tournament’s Most Outstanding Player three times. The sports press and wire services acclaimed him as College Player of the Year in both 1967 and 1969.

Although he enjoyed enormous popularity as a college sports star, Alcindor was also an independent thinker, threading his way through the complex moral and political issues of the 1960s. A reading of The Autobiography of Malcolm X led him to the study of Islam, a faith he eventually embraced, converting from the Catholicism of his family. Alcindor was urged to play on the United States Olympic team in 1968, but he declined, in part due to his distaste for the leadership of the International Olympic Committee, whose President, Avery Brundage, had expressed admiration for the government of Nazi Germany before the Second World War.

Alcindor graduated from UCLA with a B.A. in history in 1969. The last-place Milwaukee Bucks of the National Basketball Association won a coin toss with the Phoenix Suns and drafted the college star. In his first season in the pros, Alcindor’s impact was immediate. He led his team to second place in the Eastern Division, and personally finished second in the league for scoring. He was named Rookie of the Year. The Bucks improved their line-up by shrewd trading during the off-season, and in the 1970-71 season the team had 68 wins, including a record-setting 20 in a row. Alcindor was accumulating the first of the many records he was to accumulate in his long career. At the end of the regular season, he was named Most Valuable Player. The Bucks swept the finals that year, and Alcindor was named Most Valuable Player in the finals as well. He was also the league’s top scorer for the first — but not the last — time.

Immediately following this first championship season, Lew Alcindor adopted the Arabic name, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, meaning “noble servant of the powerful One.” In the 1971-72 season, Abdul-Jabbar was again the NBA’s scoring champion. He was voted the Most Valuable Player in that season and again the following year. In his first seasons as a pro, he had established himself as a dominant figure in professional basketball, but he was notably unlike the star centers who had previously ruled the sport. At 7 feet, 2 inches tall, he cast a long shadow, but he weighed a lean 225 pounds, far less than other players his height. The position of center had traditionally been occupied by large players, who could dominate by sheer strength, but Abdul-Jabbar brought an unprecedented agility to the position. His nimble performance on the court was the product of an intensely disciplined training regimen, far beyond what other basketball players at the time were willing to submit themselves to. He combined his speed and grace on the court with the devastating sky-hook, a shot he could perform with either hand, from the top of his impressive jump. The shot was almost impossible to block, and sportswriters dubbed it “the ultimate weapon.”

In 1974, Abdul-Jabbar suffered a scratch on the cornea of his eye during a mid-game collision. A broken hand suffered in the same incident kept him off the court for 16 games. After that, he wore protective goggles on the court, to prevent further damage to his eye. The goggles became a trademark, and made him the most easily recognized player in the game. The aging of some of Abdul-Jabbar’s Milwaukee teammates led to a decline in the Bucks’ fortunes in the mid-’70s. After making it to the finals in 1974, the Bucks dropped to last place the following year.

Despite Abdul-Jabbar’s stellar performance in Milwaukee, he felt out of place in a northern Midwestern city with no substantial Muslim community. He requested to be transferred, either to New York, where he grew up, or to Los Angeles, where he had enjoyed such acclaim as a college athlete. In 1975, he was traded to the Los Angeles Lakers, where his arrival revitalized a faltering team. Abdul-Jabbar was voted Most Valuable Player in his first year with the Lakers. In his second season, the team finished in first place and Abdul-Jabbar was named Most Valuable Player for the fifth time in eight seasons, tying the existing record for MVP honors.

Despite his fame, Abdul-Jabbar remained a deeply private person, and was visibly uncomfortable with the attention of the sports press. The next two seasons were unhappy ones for the Lakers, and Abdul-Jabbar missed 20 games in the 1977-78 season after breaking his hand in a scuffle with a player from his former team, the Milwaukee Bucks. The resultant bad publicity, compounded by his natural reticence, made this period a low point in Abdul-Jabbar’s career, but better times were just around the corner.

In 1976, Alcindor took up the practice of yoga to improve his flexibility. He also studied with martial arts master Bruce Lee and made his motion picture debut alongside Lee in the 1978 film Game of Death. He would also make a memorable appearance in the classic film comedy Airplane (1980).

The Lakers’ acquisition of the rookie Earvin “Magic” Johnson gave Abdul-Jabbar the support he needed to win five more championships for the team. In 1980 the Lakers won the NBA championship, and Abdul-Jabbar won his sixth Most Valuable Player award, setting a record that is likely to stand for many years to come. By their mid-30s, most basketball players have retired, but Abdul-Jabbar kept playing, staying in faultless condition through an ever more demanding fitness program. He augmented his practice of yoga and martial arts with meditation to relieve pre-game stress. On April 5, 1984, he scored his 31,420th point, to become the NBA’s all-time scoring champion, a record he still holds as of this writing and for the foreseeable future.

In the middle of the 1980s, some fans and writers began to wonder if Abdul-Jabbar was finally running out of steam. The Lakers lost the 1984 finals to the Boston Celtics, their principal rival throughout the decade. In the 1985 finals, the Lakers faced the Celtics again. In the first game of the series, Abdul-Jabbar performed below expectations and the Lakers lost the game. His comeback in the second game was a sensation; he scored 30 points and led the team to victory in the game and in the series. Abdul-Jabbar was once again named Most Valuable Player in the final series. Abdul-Jabbar and the Lakers beat the Celtics in the 1987 finals as well. Now 40, he signed a new two-year contract with the Lakers. Abdul-Jabbar led the Lakers to one more championship in the 1987-88 season. Over the course of the decade, Abdul-Jabbar and his teammates had made it to the finals eight times, winning five championship titles.

The 1988-89 season was Abdul-Jabbar’s last playing in the NBA. His final game was the occasion of a massive outpouring of sentiment from his teammates, fans and the general public. The onetime maverick of the league had become the beloved elder statesman. After 20 seasons, he retired with nine NBA records, many of which still hold. His scoring record of 38,387 career points (24.6 per game) will probably never be equaled. In 1995, he was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Since retiring from active play, much of his time has been devoted to writing. His first book, an autobiography published in 1987, was titled Giant Steps, after a tune by one of Abdul-Jabbar’s heroes, jazz saxophonist John Coltrane. A second memoir, Kareem (1980), is a diaristic account of his last season, interspersed with memories of childhood and reflections on his life in basketball.

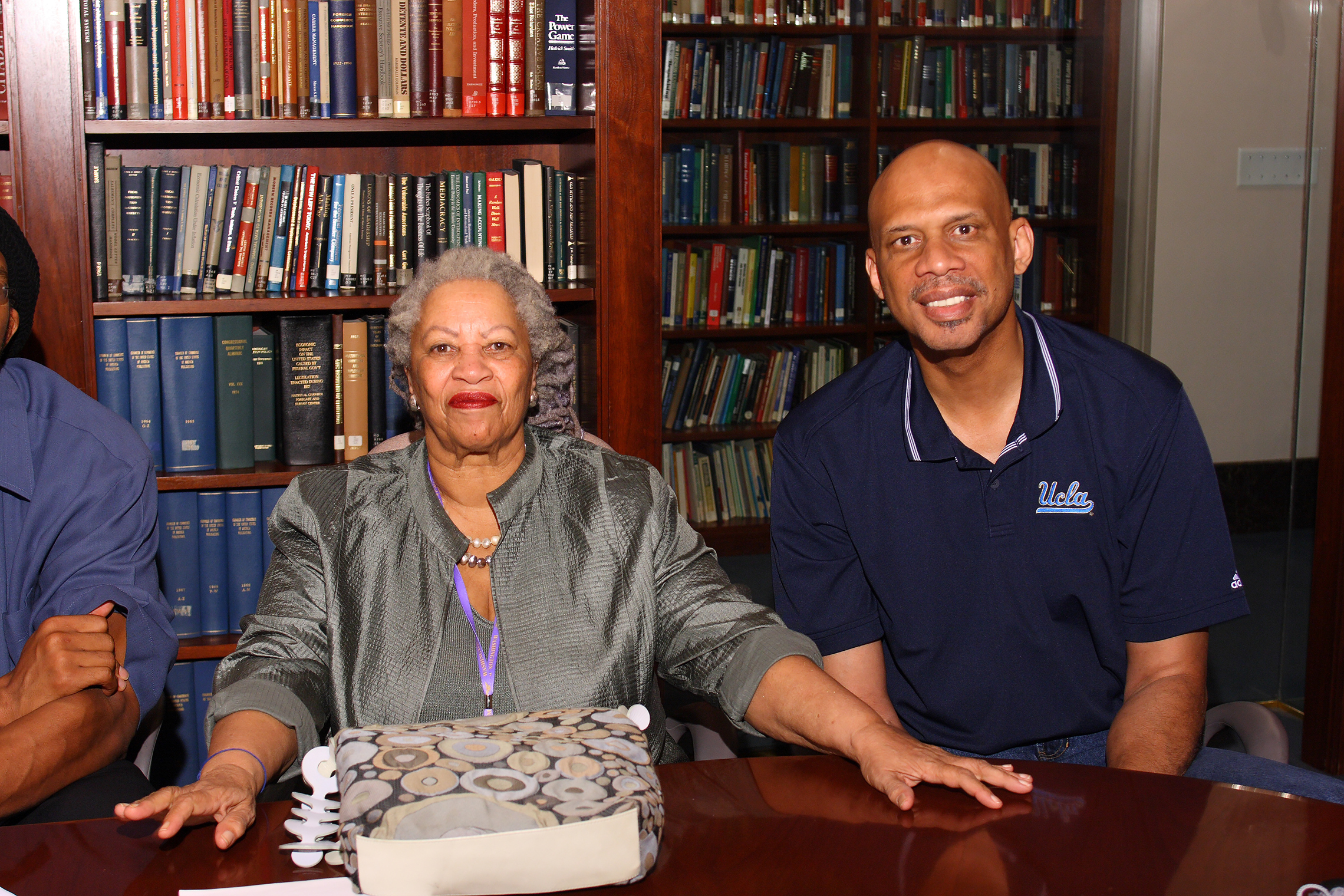

Although he has worked as an assistant coach for the Los Angeles Clippers and the Seattle Supersonics, and as Head Coach for the Oklahoma Storm of the United States Basketball League, his most interesting coaching experience was as a volunteer at Alchesay High School on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation in Whiteriver, Arizona, an experience he recounts in A Season on the Reservation. Subsequent books include Black Profiles in Courage: A Legacy of African American Achievement, and Brothers in Arms, the story of the all-black 761st Tank Battalion in World War II. His latest is On the Shoulders of Giants, an examination of the poets, artist, musicians, athletes and activists of the Harlem Renaissance, informed by his own experience growing up in Harlem, a neighborhood historically poor in material resources, but rich in African American history and culture.

Since 2005, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar has also worked as an assistant coach with his old team, the Los Angles Lakers, sharing with a new generation of players the hard-won wisdom of his own inspiring career. In 2009, he founded the Skyhook Foundation, which fields an elite all-star traveling basketball team of middle school and high school youth in partnership with the Boys & Girls Clubs’ College Bound program. The Skyhook Foundation emphasizes the values of discipline, leadership, teamwork and conflict resolution that make for excellence on the basketball court and in the classroom. At-risk students participating in the program are given continuous attentive support to facilitate their progress towards higher education.

In November 2009, Abdul-Jabbar announced that he had been diagnosed with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia. This rare form of the blood and bone marrow cancer is manageable with medication. Abdul-Jabbar made this announcement almost a year after first receiving the diagnosis. Since he responded well to medication, he has shared his experience with the public to promote greater understanding of leukemia and its treatment.

In the years since, Abdul-Jabbar has continued to pursue an impressive variety of philanthropic and cultural endeavors. He co-wrote and served as executive producer of a 2011 documentary film based on his book On the Shoulders of Giants. The film focused on a historic match played by the first all-black professional basketball team, the Harlem Rens, and featured interviews with Maya Angelou, Bill Russell and John Wooden, as well as music by Wynton Marsalis. In April 2015, the 68-year-old Abdul-Jabbar received a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease. Shortly after receiving his diagnosis, he underwent quadruple bypass surgery and has made a complete recovery.

In 2016, President Barack Obama recognized Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s contributions to American society with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. The President noted that Kareem Abdul-Jabbar had dominated professional basketball, along with fellow recipient, Michael Jordan. Citing the NCAA’s banning of dunking during Abdul-Jabbar’s time in college, Obama said, “when a sport changes its rules to make it harder just for you, you are really good.”

The NBA paid tribute to Abdul-Jabbar’s lifetime of social activism by creating the Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Social Justice Champion Award. The NBA will donate $100,000 to the organization of the honoree’s choice. The award will be presented in 2021 and every year thereafter to the player who best embodies Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s striving for social justice and racial equality.

In February 2023, LeBron James became the association’s all-time leading scorer in the Los Angeles Lakers’ game against the Oklahoma City Thunder, surpassing the record that six-time NBA MVP Kareem Abdul-Jabbar had held for 39 years.

It would be difficult to name another athlete who dominated his sport as long or as completely as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. The greatest all-around player in the history of professional basketball, he ruled the sport through speed, agility and a devastating ambidextrous “sky hook” shot that sportswriters dubbed “the ultimate weapon.”

In the three seasons he played for the UCLA Bruins, he led the team to three NCAA championships and was named Most Outstanding Player in all three years, the only player in the history of the college game to hold this distinction. As a professional, his career was even more remarkable. In his 20 seasons in the NBA, he played in 19 All-Star Games, won six championship titles and six Most Valuable Player awards. Over the course of his career, he blocked more than 3,100 shots, made 17,400 rebounds and scored 38,837 points, making him the highest-scoring player in NBA history, a record that may never be broken.

Adored by his fans and revered by his teammates, he retired to the most heartfelt tributes in sports history. Since retirement, he has chosen to pursue a second career as an author, enjoying success with books on African American history, World War II, the Harlem Renaissance and his own experiences coaching basketball on an Apache Indian reservation. One of the most durable athletes in the history of any sport, he has gone on to earn the world’s enduring respect for his accomplishments as a human being.

What was it like playing for Coach John Wooden at UCLA in the 1960s? Were your teammates serious students?

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: When I was at UCLA, all of my teammates were serious students — well, not all of them, but most of them — and that was because Coach Wooden expected that. He wanted us to graduate. He let us know in the recruiting process that he wanted us to go to class and do well. He was just like a parent, a strict parent. He wanted us to do well. He was not someone that was just there to exploit us as athletes, and I have a lot of respect and undying love for Coach Wooden for that reason. He was not just some cynical opportunist. He really tried to show the love and caring that he had for the people that played sports for him, that was very important.

Are there any particular lessons that you take away from your relationship with Coach Wooden?

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: Gee, there are so many things that I learned from Coach Wooden that had nothing to do with sports. Coach Wooden really made us think about things beyond just playing basketball, and that was a very wonderful thing to have coming from the head coach. I started out as an English major and Coach Wooden, I could talk to him about the fine points of the English language — whether to use a colon or semicolon, when to use parentheses, what was appropriate, “like” or “as” — those types of things that an English major can tell you are confusing and can be kind of daunting at times. And it had nothing to do with sports. So for that reason alone, I really thought that I was in the right place and dealing with the right situation.

Those years you were at UCLA were turbulent years in America. How did that affect you?

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: I think the turbulence of the ’60s affected everybody, no matter where they were — the Vietnam War, and the divide that happened to people lining up on either side of that. Also, the mid and late ’60s really were the culmination of the Civil Rights Movement, and all those things affected me on the campus at UCLA, but I thought I was in a very positive environment there. The people in and around UCLA seemed to have the right ideas on those matters, and I didn’t ever feel that I had made a bad choice.

In 1968, you could have gone to the Olympics and played on the American basketball team, but you declined the invitation. Why was that?

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: I declined the invitation to go to the Olympics because I didn’t feel that the Olympic situation was reality. Here we have this whole appearance of racial harmony on the American Olympic team when things weren’t that harmonious here. In addition to that, I had a very good summer job that paid me a pretty good salary, and I needed that to tide me over for the school year, and I couldn’t do both things. So I figured I had better go with what was going to benefit my life, as opposed to benefiting the Olympic movement, which I saw as very hypocritical.

The gentleman that was in charge of the U.S. Olympic team, Avery Brundage, to me, was a very controversial figure. I believe in the 1930s he had supported the Nazi Party at one point. It was not somebody I wanted to work for. I didn’t want to deal with him or the Olympics, so it was pretty easy for me to make my choice.

You must have taken some heat for that.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: I took a lot of heat for that, but I had good reasons not to go. I thought it would be better if I didn’t go, as opposed to going and being a problem for everybody, and being a disruptive element there. I let them do their thing, and I was going to do my thing.

A lot of big men have played basketball without ever becoming the kind of player you were. How do you account for your achievements on the basketball court?

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: I think my achievements on the basketball court came from a whole lot of things coming together in one place and one person. I was able to learn the game from some of the best teachers, and I had particular skills that translated well to playing the game. So the knowledge that I had and the physical gifts that I had gave me the opportunity to be a very good player, and I was able to take advantage of that.

By the same token, there have been teams with very talented players that never won an NCAA or NBA championship. What does it take to win a championship at any level?

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: In order to win a championship, you have to have a lot of parts that fit together, and you have to have the opportunity to win. So in order to win, you really have to have a lot of things happen the right way. You have to have good leadership, coaching, and you have to have a talented team that can come together as a unit. And I think the reason that UCLA’s teams did so well was that Coach Wooden’s ideas on unity and team play really were cutting edge and the best. He taught those elements of the game the best of any coach in the country. You combine that with talented athletes and you’re going to have a winning program.

There is a story that is always told about Coach Wooden, that he would teach his teams how to put their socks on. Do you remember that? How did that help you become better teams?

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: The first day that you go to play for Coach Wooden, he tells you about how to put your socks on. And the reason he does that is because his system requires that you do everything on the run. You don’t jog through things, you have to run full speed. The wear and tear on your feet is immediate and intense, and if your socks aren’t on right, if you have like a ridge that you’re running over in your sock, you’re going to get a blister and then you won’t be able to practice, and if you don’t practice for Coach Wooden, you don’t play. So he was telling everybody how to survive his system and get through it without coming up with blisters on their feet.