I understood firsthand the problems of being a refugee. Second, it occurred to me that nobody needed to experience that kind of thing. Three, I thought that whatever I would be doing, whatever my responsibilities were, I would always try and find a way of addressing that problem.

Paul Kagame was born in southern Rwanda, to a politically prominent family of the Tutsi ethnic group. The European colonial powers, Germany and then Belgium, had exploited ethnic divisions among the country’s population, favoring the country’s Tutsis over their neighbors, the Hutu ethnic group. As the country prepared for independence from Belgium in 1959, a Hutu rebel movement fomented violence against the Tutsis, and Kagame’s family fled their home, eventually seeking refuge in the neighboring British colony of Uganda. Paul Kagame was only two years old when his family went into exile, and he began school while living in a refugee camp. It is there that he met his friend and future comrade Fred Rwigyema.

The Kagame family arrived in Uganda not long after the country gained its independence from Britain, but in 1971, the country fell under the rule of the notorious dictator Idi Amin. Paul Kagame completed his education in Uganda’s capital, Kampala, while in the countryside, rebel armies waged guerrilla warfare against Amin’s regime from bases in Tanzania. On graduating, Kagame traveled to and from Rwanda surreptitiously to visit family members and reacquaint himself with his native land, while his friend Rwigyema joined the rebels in Tanzania.

In 1979, the Ugandan rebels, with the assistance of Tanzanian forces, ousted Amin, but the rule of his successor, Milton Obote, threatened persecution against Kagame’s fellow Rwandan refugees, and Kagame and Rwigyema joined a new armed movement against Obote’s rule, the National Resistance Army, led by Yoweri Museveni. With the resistance victory in 1986, Kagame became a senior officer in the new Ugandan army.

With his success in Uganda, Kagame’s eyes turned to his native country, and along Rwigyema and fellow Rwandan Tutsi exiles, he founded the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) and planned a war of liberation against the regime in Rwanda. In that country, leaders of the regime had turned on one another, and the RPF’s Tutsi founders were joined by moderate members of Rwanda’s Hutu ethnic group, disillusioned with the country’s Hutu-led regime.

The Ugandan army selected Kagame for advanced study at the United States Army Command and General Staff College in Leavenworth, Kansas. Kagame was in Kansas in 1990 when the RPF staged its first attack on government forces in Rwanda. Fred Rwigyema was killed in battle and Kagame returned to Africa to become the movement’s military commander. By 1993, Kagame’s RPF had made significant territorial gains in Rwanda, and the Rwandan government agreed to a ceasefire.

The combatants were negotiating a peace settlement when an airplane carrying Rwanda’s President Juvénal Habyarimana was shot down approaching the capital city of Kigali. Habyarimana died in the incident, and extremist Hutu leaders called for the murder and expulsion of the country’s Tutsi population. Radio broadcasters and even members of the clergy fanned the flames of ethnic hatred, and a wave of senseless killing swept the country as neighbor murdered neighbor with any tools that came to hand. In 100 days, the Rwandan genocide claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children, mostly ethnic Tutsis, along with members of the Hutu population who opposed the slaughter. Estimates of the dead range from 800,000 to a million.

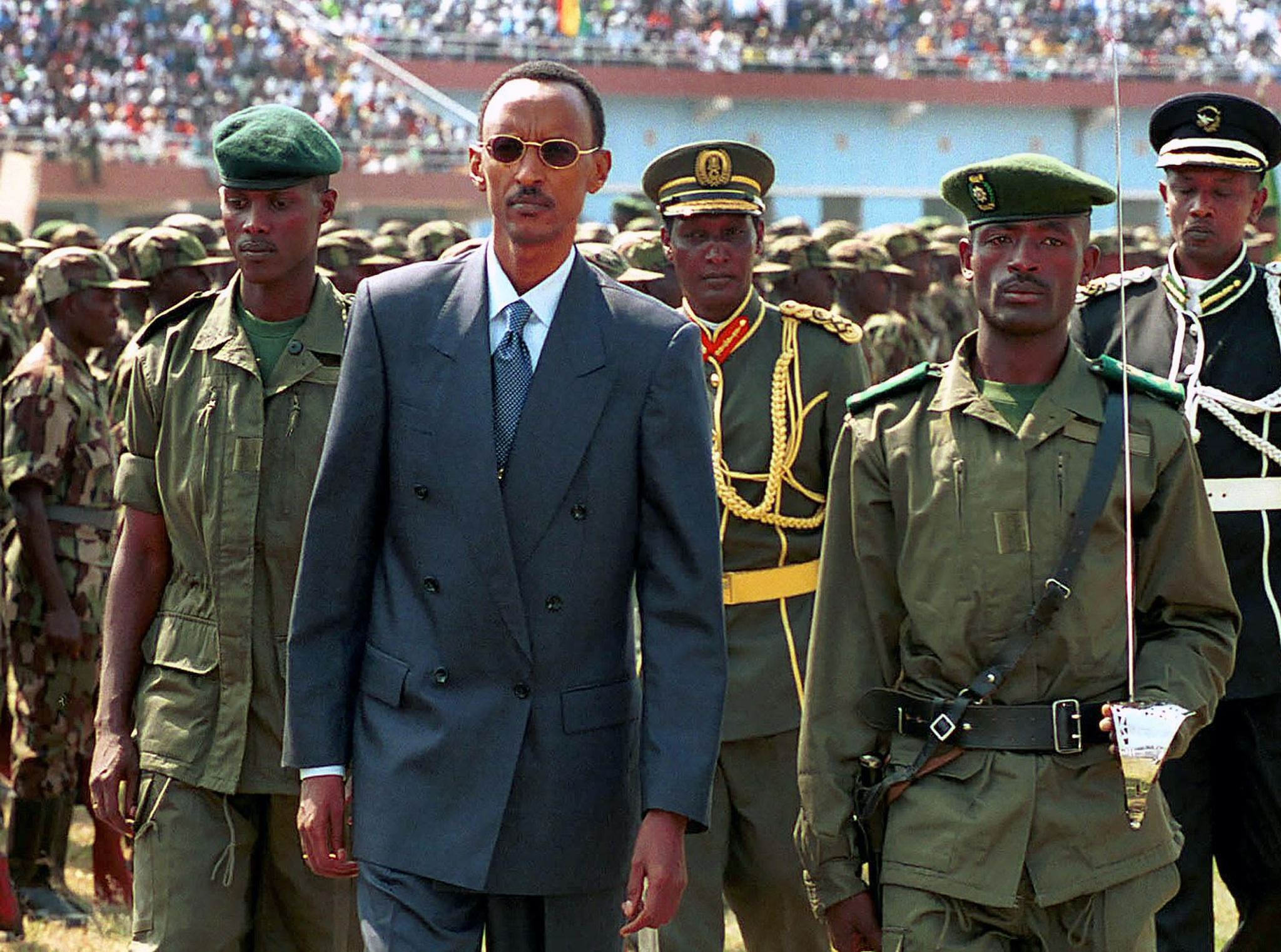

Kagame and the RPF resumed their war on the Rwandan regime, and by 1994, Kagame’s insurgency succeeded in deposing the Hutu-led government and put an end to the mass killing of their countrymen. Pasteur Bizimungu, an ethnic Hutu spokesman of the RPF, became the new president, and Paul Kagame was named vice president and minister of defense. Kagame moved quickly to restore law and order and prosecuted a number of his own RPF soldiers who had participated in reprisal killings.

Instigators and perpetrators of the genocide, known as genocidaires, regrouped and carried out raids from refugee camps in neighboring Zaire. Kagame’s army pursued the genocidaires into Zaire, and Rwanda became embroiled in the country’s civil war. A rebellion had erupted against Zaire’s dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, and Rwandan forces intervened in support of the rebels. In a conflict known as the First Congo War, the rebels, with support from Rwanda, Burundi, and Uganda, deposed Mobutu, and Laurent-Désiré Kabila became president of the country, renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Tensions appeared quickly between the new Congo government and its neighbors, and Rwanda and Uganda intervened for the second time. The conflict escalated into a regional war, known as the Second Congo War or the Great War of Africa, involving nine countries and as many as twenty separate armed factions.

The war impeded Rwanda’s troubled process of reconciliation, and in 2000, President Bizimungu resigned and Paul Kagame succeeded him as president of Rwanda. In 2003, Rwanda adopted a new constitution and Kagame was elected to his first full term as president. That year, Kagame agreed to an international peace settlement and the Congo’s long war came to an end. Rwandan forces were withdrawn from the Congo and the DRC agreed to disarm and repatriate the Rwandan Hutu insurgents on its territory.

Kagame was now free to pursue the process of reconciliation and economic development. He announced a program he called Vision 2020, with the goals of achieving middle-income status for his country by the year 2020. From 2004 to 2010, the country averaged eight percent annual economic growth and continues to meet milestones in education, income and other measures of development.

President Kagame has attempted to promote a sense of national unity, transcending historic ethnic differences, although old rivalries continue to threaten Rwanda’s hard-won peace. Former President Bizimungu was imprisoned in 2004 for attempting to form an armed militia, but President Kagame pardoned him in 2007. Genocide denial is a crime in Rwanda, but foreign observers and Hutu dissidents claim the law has been used to suppress freedom of the press and opposition parties. Kagame and his supporters believe the dangers of denial, including the possibility of resumed ethnic violence, justify legal limitations on the discussion of Rwanda’s tragic recent past.

In 2009, a French court accused Kagame of orchestrating the death of President Habyarimana, but Rwandan investigators have concluded that the presidential plane was shot down by Hutu extremists seeking to derail the peace process. Diplomatic relations with France were suspended over the accusation. Elected to a second term in 2010, Kagame has pursued close relations with the United States and the East African Community and sought an improved relationship with France. He was elected to a third seven-year term in 2017. A controversial revision of the country’s constitution permits President Kagame to run for two further terms of five years each.

As leader of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) in the 1990s, Paul Kagame headed a successful insurgency against the Hutu regime that had murdered over a million of Kagame’s fellow ethnic Tutsis and many of their Hutu countrymen.

When Kagame assumed the presidency in 2000, his country was embroiled in a seven-nation conflict that threatened to engulf the continent. President Kagame joined a regional ceasefire in 2003, and since then has dedicated his country’s energies to economic development. Rwanda is now experiencing rapid economic growth and has made dramatic progress in health care and education.

With President Kagame’s leadership, Rwanda is overcoming the lingering trauma of civil war and genocide. The president enjoys a high level of popularity, although he is an ethnic Tutsi presiding over a majority Hutu nation. He has outlawed hate speech, abolished the death penalty, and joined the UN declaration of LGBT rights. Today, Rwanda enjoys the world’s highest representation of women in its national parliament. In 2017, Paul Kagame was elected to his third full term as president.

Mr. President, your country endured an almost unimaginable calamity in 1994, the attempt by the government to annihilate the Tutsi population, minorities and dissidents. What was it like to run to a country in which nearly every tenth person had been murdered?

What happened in 1994, of course, was on the scale that no one imagined, but we had had a history of killings in Rwanda since 1959. In fact, during that period we became refugees. There were many killings between 1959 and 1961. So many killings had been taking place, and that’s how people ran to different parts of the region. They were running away from these political killings. But throughout the years, up to the time we started the armed struggle in 1990, there had been oppression. There had been killings of people, targeted people. All along, a section of our population was the target from the ‘60s up to that moment, but the scale of this one was more than anyone could imagine. But during the fighting — during 1990 to ‘94 — what was happening — in ‘91, ‘92, ‘93, there were always indications that something like what happened in many years before could easily happen. Because the government was so much whipping up sentiments — ethnic sentiments — and saying, “These people are returning. They are the same people who survived the killings of the ‘60s…” and so on. “After all, these are foreigners. They shouldn’t be around to go back to home, you know. They should stay where they are. The country’s very small. It’s only for another section of the oppression of Rwanda, not for these ones who are foreigners,” and you could see they were building up these — and, in fact, they started arresting people. They started killing them in different parts of the country, those who had stayed in the country who were never refugees but who were identified as this group that they should exterminate.

When you look back at the genocide, is there anything you can imagine could have been done differently to avert this? Some mistake we can identify and never repeat?

Paul Kagame: It was ‘61, then ‘66, many killings. Then ‘73, so many killings. In fact, they had — some of my sisters had stayed. I have four sisters, and I had a brother who died in the struggle in Uganda. But two of my sisters had stayed in the country with relatives. They didn’t flee with us. They stayed with those who stayed. But in 1973, they actually ran away this time, and they became refugees because they almost killed them. So you can see, there were killings in ‘61, there were killings in ‘73, and then there were killings at this time. And as I mentioned to you — so unless one could really say, “If the war had not started, if we hadn’t waged an armed struggle, probably that would not have happened.” But that would only be leaving it to saying, “No, they could kill like they killed in ‘61. They could kill as they killed in ‘73. So let those killings of a certain low number — a small number — continue, and so continue with the people having no right to their country. Maybe this is the best way to manage it.” So if we hadn’t waged an armed struggle, maybe these things wouldn’t have happened.

We know you’ve done a lot to achieve reconciliation in Rwanda, but how do you now deal with the fact that other countries didn’t intervene while this was happening?

Paul Kagame: I have come to settle to the idea and understanding that problems of any country, or later on — I mean if we start with mine, my country, and my country’s problems, they will never be settled by people from outside. Never. I haven’t known of any country where problems of this kind are resolved from outside, rather than people themselves from inside. I don’t know of an example, so the outside having not helped, well, we can spend a lot of time blaming people or others, but we are not expected to do it anyway from experience. That’s what I know. That won’t be solved.

But don’t you blame others for what happened?

Paul Kagame: I’ve found some logic that helps me to not spend so much time blaming people —other people — for the genocide, much as even the origin of it was contributed from outside. It has a history. You can trace it from outside, but it wouldn’t work unless conditions inside of the country allowed it to take the shape it did. So in other words, we are to blame, too, we Rwandans. And in the end, whoever — when it came from outside, maybe people from outside were very clever to start something and let us be the ones to carry it out. And it would be outside, as innocent people who would come to rescue us, when they’re the ones who actually started it. You see my point? So if we hadn’t really taken on this kind of politics that divides our society that later on ended in a genocide, we ourselves, if we hadn’t — meaning the Rwandans who were in power from independence up to the time this happened — for us, the blame — if one may call it so, meaning from outside, we, the refugees — is that we fought a war to better our country, to better ourselves. Maybe somebody comes along and says, “You shouldn’t have done that.” But my question would be, “What did you want me to do?” Well, if somebody goes, “Oh no, you should have stayed as Ugandan and become Ugandan.” Yeah, but there’s somebody somewhere else.

So you’re not sorry you made war against the government?

Paul Kagame: I was more than happy to get involved from the beginning. And by the way, we agreed, risking my own life — like many other people risked and even lost their lives — this was something much bigger than just feeling comfortable in Uganda, where I was, or somebody else, wherever they were, and saying, “No, no, no. This has gone on for too long. We are stateless. We are refugees.” We couldn’t just allow ourselves to live at the mercy of people, where we were refugees, or where somebody could decide what happens to us and what should not happen to us. No, this was something that any of us was happy to have stood up and fought against.

Now, as you work to rebuild and unite your country, what achievement are you most proud of?

Paul Kagame: Very happy, very proud, apart from the loss of many lives, which can never be corrected, or we can’t do much about it. It’s probably the most expensive part of the struggle. But to have won the war and won the peace for ourselves, because if you look at those years of the war, of the genocide, and they are brought to an end, and then we started building and rebuilding and a sense of reconciliation, a sense of allowing Rwandans to live together as a nation. And now a proud people of Rwanda, and socially made progress politically, significant progress, economically the same. I think we could not have asked for more.

Looking back, what was the key to winning the peace? Was there a single decision that you think has made peace possible?

Paul Kagame: It will never be one single thing. It’s normally going to be a combination of things, but it builds around a determination, a single-mindedness of all of us coming together and saying we need to change the course of history and politics in our country, and we are one nation. We are different. We will be different, but we can use this difference to build rather than destroy what belongs to all of us. So that organization, that coming together, that vision, and deciding that this is what we deserve is really — so for that, you need to have vision, leadership, and organization, organization which brings in people to be part of that vision and to feel they own it.

What do you say to people who are angry? If their neighbors killed their family, they must want revenge.

Paul Kagame: It’s painful. It’s very hard even to explain. In fact, I remember, on one occasion we were commemorating the genocide. Every year we do it. Every 7th of April of every year we do that. We remember our people. And I remember there was a story. Indeed, the survivors and others were agitated, and rightly so, and were saying, you know, it’s like the story of the cost of reconciliation is only carried by them. Meaning they are the ones who lost people, and they are the ones who suffered, but they are always asked to do something so that the reconciliation process succeeds. And they had to engage them at various levels, and had a discussion with them and had even to make a public speech on that day, telling people that, first of all, we hear them. We are part of them. This is not that we are dealing with a foreign situation or a foreign idea or anything. It’s us. They and us are the same. There’s no distinction. And that the reason, the fear — or anybody would see that they are the ones carrying the burden — is to be explained only by one, and I put it to them, I said, “Yes, I can come to you and look you in the eyes and ask you to forgive and not forget, and I am with you on that. But it’s only you that I can ask that, and it’s only you that can be asked to do something about this story of Rwanda.” Because I can’t go to the perpetrators and ask them anything. There is nothing to ask from them. I can’t go to these ones who killed, who are in prison or who are wherever they are, and say, “Please forgive us, and next time don’t behave like this.” No. I said, “There’s nothing to ask from these people. They are condemned. They killed, carried out a genocide of other people. We just have to decide what to do about that.” We don’t even have to ask their consent because they have condemned themselves to being in a situation where forgiveness — they should be forgiven or they should be tried. “So there’s nothing to ask of these people, but there’s a lot to ask from you.” And this conversation helped people to understand and say, “Oh, this is why we carry the burden.” And I said, “You — we — lost people. Your people, our people. I lost many relatives in the genocide. So when I’m saying this, I’m with you. I’m one of you. But we need to live beyond this tragic story. We don’t need any more, and the only way is to ask you — is to ask ourselves — to forgive but not forget.” Yes.

Your country, Rwanda, now has a female majority in Parliament. That’s very unusual. How did that come about? Is that something you specifically tried to achieve?

Paul Kagame: We pushed that from the beginning, to have women be in their rightful place, and that — from the beginning, even in our conversations with different people, leaders of our country at different levels, I have always emphasized that this is not doing them a favor. We are not doing women any favors. It’s their right. We are only allowing them to have their rights. In fact, even in a joke, I say, “If these women were like me, growing up and having to take up arms to fight for my right, maybe these women should take up arms and really fight those who are denying them their rights.” But the situation is such that we can handle it differently. There’s no need for there to be fights. Generally, women are 52 percent of our population. Right? And from what I said, that being their right, I think if you give 52 percent of our population their right, that’s sort of the big thing. That’s huge, but now in Parliament — 64 percent — so I’m just saying, even if things just remain the same — that these are just rights being realized — you’re already gaining. But now, 52 percent of the population empowered and being part of whatever is happening in the country, you gain socially, you gain economically, you gain in all ways. Now when we have them in Parliament, 64 percent, and Parliament making laws and so on, they are already helping this transformation.

Is there a woman you’d like to see succeed you as president?

Paul Kagame: I don’t want to think about that from such an early stage because it might even create problems for her. I know there’s no need because I may mention somebody and then after that, I realize that so many other women probably deserve it or are more qualified. So I wouldn’t want to do that. That should happen at the right time. Every time you are scanning and looking around, wanting to see the evolution of things, and then people as they call out different — there are so many women at leadership level, and they are doing amazing things, you know. They are part of this success story of Rwanda, and you don’t want to zero on one woman so early when there are so many wonderful women who can. Whereas there are men — there are many — when you are talking about women and so on, we are not really saying that men aren’t there or useful or considered, but I think we men have dominated this for a long time.