Even if you meet Prince Charming, be able to fend for yourself.

Ruth Joan Bader was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. Her mother Celia was born in the United States to immigrant parents newly arrived from Austria; her father Nathan immigrated to the United States from Russia at age 13. The Baders’ first daughter died when Ruth was only two.

Although Nathan Bader never attended high school, he achieved some success as a fur manufacturer, while Celia worked in the home and helped with the family business. While Mrs. Bader never pursued a career of her own, she encouraged Ruth’s scholarly and professional ambitions, taking her to the library every week to keep her supplied with books. Celia Bader suffered from poor health throughout Ruth’s teen years, dying of cancer the day before Ruth graduated from James Madison High School.

At Cornell University, Ruth Bader earned a bachelor’s degree with high honors in government and distinction in all subjects. It was also at Cornell that she met her future husband, Martin Ginsburg, on a blind date. They were married shortly after Ruth Bader’s graduation, and lived in Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where Ginsburg completed his military service. Following his discharge, he started legal studies at Harvard, and 14 months after the birth of their daughter, Jane, Ruth too entered Harvard Law School.

One of only nine women in a class of more than 500, Ruth encountered resistance from some of the older faculty. The law dean asked all the women students to justify taking places at the school that could be occupied by men. While attending Harvard, Martin Ginsburg was diagnosed with testicular cancer. During his illness, Ruth attended his classes, as well as her own, and typed all his papers. Even with the added responsibility of caring for her ailing husband and their child, she won a coveted seat on the Harvard Law Review. Martin Ginsburg made a complete recovery, and after completing his studies at Harvard, joined a law firm in New York City. In the next few years, he became a highly regarded expert on tax law.

To keep her young family together, Ruth Ginsburg transferred to Columbia University in Manhattan for her last year of law school. At Columbia too, she won a seat on the law review. Serving on both the Harvard and Columbia law reviews was an unprecedented achievement for any law student, male or female. Ginsburg graduated from Columbia tied for first place in her class.

Despite this stellar academic record, she found her sex a barrier to career advancement. A firm that had employed her between terms at Harvard failed to provide a permanent position. Of the 12 firms with which she interviewed, not one offered her a job. Although Professor Albert Sachs of Harvard personally recommended her to Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, the Justice declined to offer her the post of law clerk, apparently too uncomfortable with the thought of a woman in his chambers.

Ginsburg was eventually offered a clerkship with Judge Edmund G. Palmieri of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, where she served from 1959 to 1961. Following this experience, she finally received several offers from major law firms, but instead returned to Columbia, to work on the law school’s Project on International Procedure. She became associate director of the project, taught herself Swedish and traveled to the University of Lund to study the Swedish legal system. In 1963, she became a professor of law at Rutgers, the state university of New Jersey. While there, she completed a textbook, Civil Procedure in Sweden (1965), published the same year her son, James, was born. In 1970, Ginsburg co-founded The Women’s Rights Law Reporter, the first law journal in the United States devoted to gender equality issues. Two years later, she moved from Rutgers to Columbia University Law School, and became the first woman to receive tenure there. In 1973, she argued her first case before the United States Supreme Court. After the American Civil Liberties Union referred a number of sex discrimination complaints to her, she founded the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project. She became the project’s general counsel, as well as serving on the national board of the ACLU. At the time, she was writing the first textbook on sex discrimination law, Text, Cases, and Materials on Sex-Based Discrimination, published in 1974.

In these years, she also began to speak as a visiting lecturer at law schools and other institutions in the United States and Europe, including the law schools of Harvard and New York University, the Universities of Amsterdam and Strasbourg, the Salzburg Seminar in American Studies, and Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences.

Ginsburg continued to appear frequently before the Supreme Court, arguing cases of sex discrimination. One of the most important of these was Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld (1975). Stephen Wiesenfeld was a widower who had been denied the Social Security child support benefits that a woman would have received in the same situation. Her victory in this case was followed three years later by another in Duren v. Missouri. State law in Missouri had made jury duty compulsory for men but optional for women. Ginsburg argued that this devalued women’s contribution as citizens, and once again Ginsburg’s position prevailed. By this time, she had earned a national reputation as a leading advocate for the equal citizenship status of men and women.

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter appointed Ruth Bader Ginsburg to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Martin Ginsburg followed her to Washington, where he continued to practice tax law as well as becoming a Professor at Georgetown University Law Center. Their daughter, Jane Ginsburg, followed her parents into the legal profession, and became a law professor at Columbia. Their son, James, shared his mother’s love of classical music. He became a record producer and founded his own label, Cedille Records, based in Chicago.

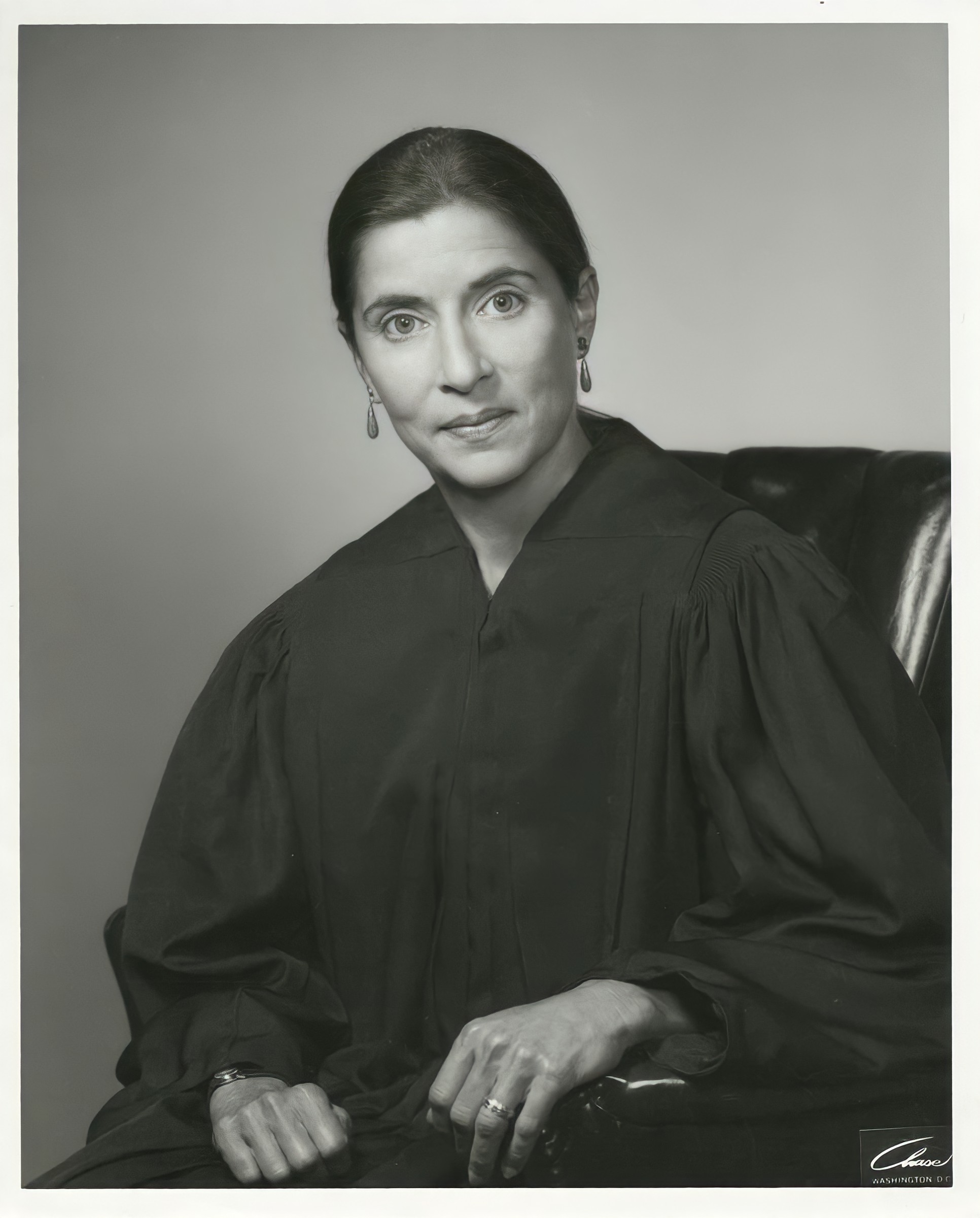

After Ruth Bader Ginsburg had served 13 years on the Court of Appeals, President Bill Clinton appointed her to the Supreme Court of the United States. She would fill the vacancy left by retiring Justice Byron White, who had served since the Kennedy administration. Ginsburg was only the second woman to be named to the Supreme Court, following Sandra Day O’Connor, and was the first Jewish woman to serve.

In her Senate confirmation hearings, Ginsburg declined to answer questions concerning her personal views on a number of controversial issues, or to discuss how she might rule in hypothetical cases. She insisted this reticence was essential to maintaining her open-mindedness and integrity as a jurist. Subsequent nominees to the Court have, for the most part, followed her example. The Senate confirmed her appointment by a vote of 96 to three.

On the high court, Justice Ginsburg was often called on to rule in cases regarding the rights of women and issues of gender equality. In 1996, she joined the majority in United States v. Virginia, ruling that the state could not continue to operate an all-male educational institution (the Virginia Military Institute) with taxpayer dollars. She also joined in the majority opinion in Stenberg v. Carhart (2000), striking down a Nebraska law banning so-called “partial birth” abortions. She dissented vehemently in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire (2007), in which an Alabama woman sued unsuccessfully for back pay to compensate for the years in which she had been paid substantially less than junior male colleagues performing the same job. The U.S. Congress would later address the issue of pay equity through legislation known as the Lily Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009.

Vice President Albert Gore, Jr. requested that his oath of office be administered to him by Justice Ginsburg when he was sworn in for his second term as Vice President. Ginsburg dissented in Bush v. Gore (2000), the case that ended the Florida recount and effectively decided the 2000 presidential election. Although she was usually identified as a member of the Court’s liberal wing, Ginsburg enjoyed good relationships with more conservative members of the Court, including her only female predecessor, Sandra Day O’Connor, and her longtime friend and fellow opera lover, Antonin Scalia.

During her years of service, Justice Ginsburg was faced with daunting personal challenges. In 1999, she was diagnosed with colon cancer. She underwent surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy, all without missing a day of service on the bench. Ten years later, she was diagnosed with early-stage pancreatic cancer, and was back in court within 12 days of her successful operation. Ruth Bader Ginsburg recovered from these episodes, but in 2010, her husband Martin succumbed to cancer four days after their 56th wedding anniversary.

Following Justice O’Connor’s retirement, and subsequent replacement by Samuel Alito, Justice Ginsburg became for a time the only female member of the Supreme Court. In later years she has been pleased to welcome not one but two new female members of the Court, Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

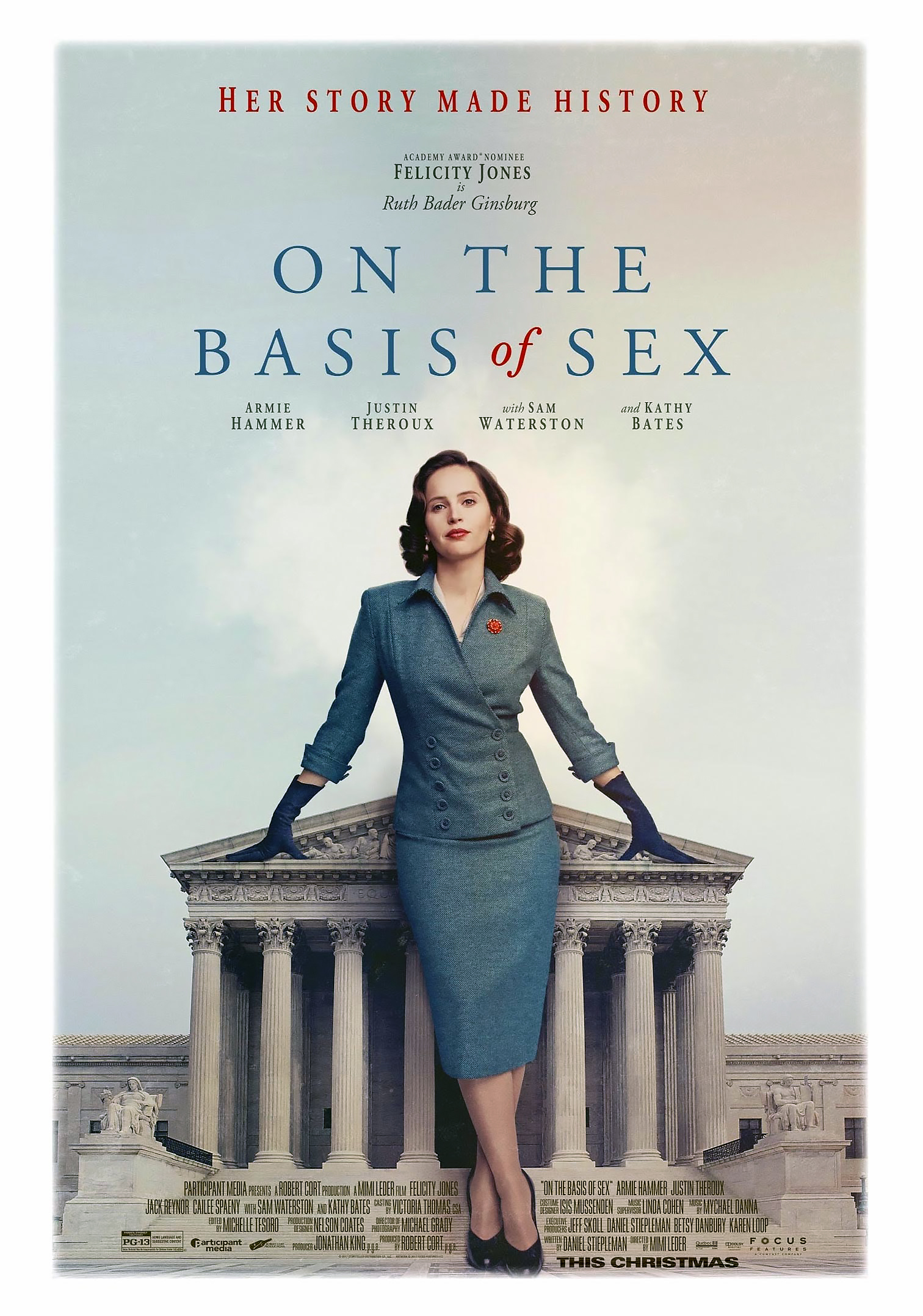

Over the years Justice Ginsburg was embraced by many Americans as a feminist icon and an exemplar of moral courage in the pursuit of social justice. Her life and work were celebrated in books such as the playful 2015 biography The Notorious RBG, and in the 2018 feature film, On the Basis of Sex, which portrays her early career and the landmark sex discrimination case of Moritz v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue.

Justice Ginsburg persevered in serving on the court through recurrences of her cancer, promising to remain on the bench as long as she was able to serve. She died at her home in Washington, D.C. at the age of 87.

The announcement of her passing called forth an outpouring of public sentiment. That evening, a crowd of admirers gathered on the steps of the Supreme Court to pay tribute to a champion of equal justice under law.

When Ruth Bader Ginsburg began her career as an attorney, America’s courtrooms and law firms were virtually all-male preserves. Female attorneys were a rarity, female judges were almost unheard of, and in many states women were routinely dismissed from jury duty.

As one of the few women studying at Harvard Law School in the 1950s, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was asked to justify taking a place in the class that could be filled by a man. Despite her outstanding academic record, law firms refused to hire her, and a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court would not employ her as his clerk solely because of her sex.

Despite these obstacles, she became one of the nation’s foremost legal scholars and a highly effective advocate for the equality of the sexes. She argued a series of historic cases before the Supreme Court, establishing the equal citizenship rights of men and women. In 1993, she herself was appointed to the nation’s highest court, where she served for 27 years, ruling on the issues of constitutional law that define the rights of all Americans.

(Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was interviewed twice by the American Academy of Achievement at the United States Supreme Court in Washington, D.C. — on August 17, 2010 and July 14, 2016. The following transcript draws on both video interviews.)

Justice Ginsburg, when did you decide to become a lawyer?

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: Oh, it was sometime I guess around the end of my second year — maybe the beginning of my third year — at Cornell.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: I had a great professor for constitutional law, Professor Robert E. Cushman. The ’50s were not a great time for the United States. There was an enormous Red Scare in the country stirred up by Senator Joe McCarthy, who saw a communist in every corner. Professor Cushman wanted me to understand that the United States was straying from its most basic values, that is the right to think, speak and write freely without big brother government telling you what’s the right way to think or the right way to speak or write. So I was working as Professor Cushman’s research assistant, and he had me follow the news to see who were the latest people in the entertainment industry who were blacklisted, and then to read transcripts of hearings before the House on American Activities Committee or the Senate Internal Security Committee. And from those transcripts I saw that there were lawyers standing up for these people, reminding our Congress that we have a First Amendment, guaranteeing free speech, and we have a Fifth Amendment guarantee against self-incrimination. So I thought that that was a pretty good thing to do, that a lawyer could have a professional career, could have a paid job, and volunteer services in bad times to help make things a little better. That’s when I had the idea that I would like to be a lawyer.

In the early ’70s, you and your husband, Martin Ginsburg, handled your first big sex discrimination case. And it was a case that he actually brought to you.

It was a tax case. Marty came into the bedroom where I worked and said, “Ruth, I think you should read this decision.” And my response was, “Marty, you know that I don’t read tax cases.” He said, “Read this one.” I did. It was the story of a man who was never married. He took care of his then-93-year-old mother. And he took what the Internal Revenue Code allowed as a babysitter’s deduction, which you could take for the care of an elderly infirm relative of any age. So he took this $600 deduction, and he was audited by the IRS, and they said you can’t take that deduction. He said, “Oh, I’ve been told that there’s an elder care just like there’s a baby care.” The people who qualified for the deduction were any woman or a widowed or divorced man. Charles E. Moritz was a never-married man. He took his case to the tax court pro se. He represented himself and he filed a brief, which was a model. No lawyer would have done such a thing, but it was just right. He said, “If I had been a dutiful daughter, I would get this deduction. I’m a dutiful son. This makes no sense.” And the tax court judge in his opinion said, “I glean that the taxpayer is making a Constitutional argument,” but the next words were to the effect, “Everyone knows that the Internal Revenue Code is immune from Constitutional attack.” So as soon as I read that decision, I said, “Marty, let’s take it.” And that’s how Charles E. Moritz became our client.

Your husband once said that this case became the mother brief for you. There were thousands of laws then — in state and federal law — that had preferences for men or women. The government said it would ruin every kind of law imaginable if you won. What were you thinking?

I call the Moritz brief the grandparent brief. First, I understood the likely reception to my argument that it’s gender-based discrimination, what was then called sex-based discrimination: “What are you talking about? Women have the best of all possible worlds. Think of jury duty. Yes, we don’t put them on the jury rolls, but if they want to serve, they can go to the clerk’s office and sign up and we will add them. So they don’t have to serve. Women are on a pedestal. They are sheltered. They are protected. And men have to go out into the large cold world and earn a living.” The laws, the statutes, both state and federal, reflected that difference. A good name for it is the separate spheres mentality.

This sphere of earning bread, supporting the family, that was the man’s world. And the women’s world, women were to take care of the house and raise the children, that dichotomy. And the laws were shaped to fit that. That’s why any woman could get the deduction in Charles E. Moritz’s case, because women, it was well known, could take care of incapacitated relatives no matter what the age. But men — in fact that was one of the arguments the government made in Moritz, that he hadn’t proved that he was capable of taking care of his mother so that the babysitter was a substitute for himself. Women would not have to prove that because everybody knows that women could take care of elderly parents. So, what we needed to show was that the image of women being on a pedestal, there was something wrong with that picture and that in fact, as Justice Brennan put it years later, the pedestal all too often turned out to be a cage. The woman couldn’t get out. She was locked in. So it was to try to promote the understanding that these so-called protective laws more often than not ended up restricting what women could do, sparing men’s jobs from women’s competition. So, how to say that in a polite way to get across the picture, that was a challenge.

After a long struggle you became a distinguished attorney and legal scholar. When did you decide you wanted to be a judge?

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: The question is often asked to me by the school groups that visit the Court, “Did you always want to be a Supreme Court Justice?” Or more modestly, “Did you always want to be a judge?” And I laugh because in the days that I went to law school, only one woman in the history of the United States had ever been a federal appeals court judge. She was Florence Allen, Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. She stepped down in 1959, the year I graduated from law school, and then there were none again. So if you were a realist as a woman, you knew that chances for a federal judgeship were slim to none. I never thought about becoming a judge until Jimmy Carter became president. And Jimmy Carter did something wonderful. He looked around at the federal judiciary and he observed, “They all look like me.” They were all white men of a certain age. But he added, “That’s not the way the great United States looks. I want my judges to reflect the greatness of the people of the United States in all their diversity. So I will appoint members of minority groups and women — not as one-at-a-time curiosities like Florence Allen — but in numbers. So then for the first time I thought, “Yes, I would like to be a judge.” Now, I had spent ten years litigating gender discrimination cases. I had been a teacher, law teacher, for 17 years. I thought it might be kind of nice to be part of the decision-making process. Before 1977 no woman who was a realist ever aspired to a federal judgeship. And then what Carter did, he appointed I think over 25 women to federal trial courts, to the federal district court bench, and then 11 of us to the courts of appeals, and I was one of the lucky 11.

Do you remember getting the call telling you that President Clinton wanted to interview you for a Supreme Court vacancy? There was a fashion issue...

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: Oh, because I had just come in from — I was in Vermont for a wedding. And the White House Counsel, Bernie Nussbaum, said, “Come meet the President. Don’t worry if you’re in your travel clothes. He will be coming in off the golf course.” So when I came to the White House, and the president walked in, he was not in his golf clothes, he was in his Sunday best. He had just come back from church. So I was kind of embarrassed by the way I looked.

It didn’t seem to harm anything.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: But it worked out just fine. Yes.

After Sandra Day O’Connor retired from the Court, you were the only woman for several years. You dissented more frequently. Finally there was the day that the Court heard the case of Savanna Redding. In your very understated way, you blew a gasket. What was it about that case that made you so mad?

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: Savanna Redding was a 13-year-old girl. She was in the eighth grade, and she was suspected of having given pills to a classmate. The pills turned out to be Advil, but Savanna was taken to the girl’s bathroom and strip-searched. And then when the strip search was over and they found no pills, she was made to sit in a chair outside the principal’s office for two hours until they called her mother and said, “Pick her up.” Her mother was infuriated. And she sued the school district for humiliating her daughter that way. And the question was, “Had the school district violated her civil rights?” The Court answered yes to that question. But the next question is, “Should there be damages, because the principal should have known that this behavior was unlawful?” and the Court said no damages. The principal is cloaked with immunity because we have never had a case like this before so he didn’t know. He didn’t know that what was done was unlawful. And that’s when I said, “Anyone who reads the Fourth Amendment protecting us against unreasonable searches and seizures, humiliating that 13-year-old girl in that way was the most unreasonable search.” There were jokes about the boys in the locker room, and the boys unclothed in front of each other, and nobody thought anything of it. And I think I said from the bench that 13 is a vulnerable age for a girl, and a 13-year-old girl is not like a 13-year-old boy. This is overwhelming humiliation for her. And I think when I said something to that effect, then the jokes stopped. There were no more jokes about the boys in the locker room. I suppose my colleagues thought of their daughters, thought of their wives, and realized then that the point I was making was well-taken.

I want to talk to you for a moment about your husband, Marty. How long were you married?

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: We were married for 56 years when he died. Yes.

He was a master chef, a master tax lawyer and law professor, and your biggest booster. You’ve said that, from the very beginning, he was not just in your corner — it was something more than that.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: Marty was always my biggest booster. He was a remarkable man. He was so sure of his own ability that he never regarded me as any kind of threat. On the contrary, I suppose he thought, “Well, if I decided I want to spend my life with her, she must be pretty good!” So he was at every stage of my life my strongest supporter.

The day after he died in 2010, you were on the bench. It was close to the end of the term and you were announcing an important decision that you’d written. You didn’t have to be there. Somebody could have announced the decision for you.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: The Chief Justice could have announced the decision. But I remembered — my pancreatic cancer surgery — I was home and recuperating for about two weeks while the Court was not sitting, and then the Court went back to sit. I told Marty, “I can’t do this. I won’t be able to sit still for two hours listening to arguments.” And he said, “Yes, you will.” And it was because of the strength that he gave me that I showed up in court that morning, and I think miraculously I was able to sit still. So I thought, “What would Marty want me to do?” and that’s why I came to the Court and read the summary of my decision from the bench.

Marty wrote you a note a few days — maybe a week — before he died. He was terribly ill. It’s a wonderful letter from a husband. We thought you might read it for us.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: I found this letter in the drawer of the stand next to Marty’s bed in the hospital, when we knew it was the end, and I was taking him home so that he could die at home rather than in the hospital. I was just checking to see that we had everything he brought with him. And on a yellow pad there was a letter to me. And it reads: “My dearest Ruth, you are the only person I have loved in my life — setting aside a bit, parents and kids and their kids — and I have admired and loved you almost since the day we first met at Cornell some 56 years ago.” He was wrong about 56. It was nearly 60 years. We were married for 56 years. “What a treat it has been to watch you progress to the very top of the legal world. I will be in Johns Hopkins Medical Center until Friday, June 25, I believe, and between then and now, I shall think hard on my remaining health and life and consider, on balance, the time has come for me to tough it out or to take leave of life, because the loss of quality now simply overwhelms. I hope you will support where I come out, but I understand you may not. I will not love you any less.” And just signed “Marty.”