I think first of all you have to be there for the right reason. You have to be there not for fame and glory and recognition and being a page in a history book, but you have to be there because you believe your talent and ability can be applied effectively.

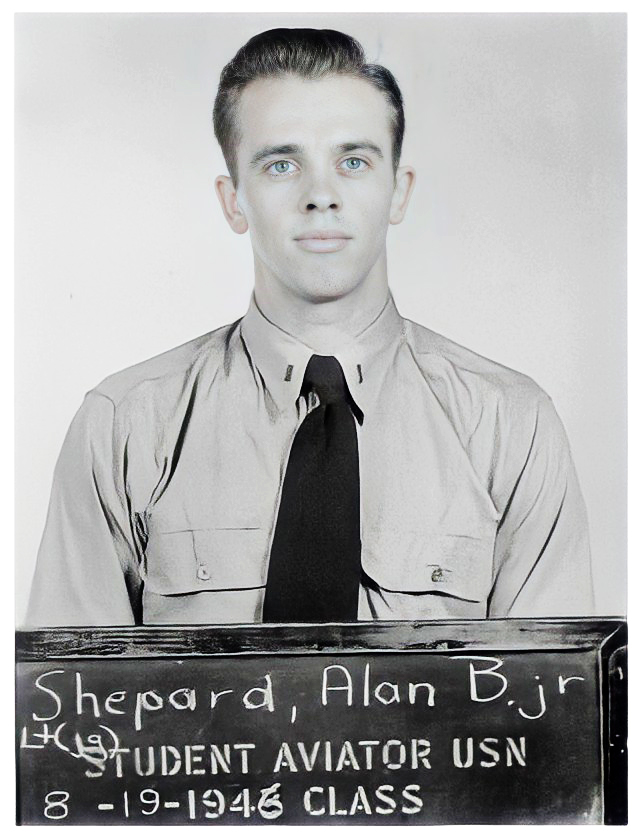

Alan B. Shepard, Jr. was born and raised in East Derry, New Hampshire. His father was a retired Army officer. Alan grew up on the family farm and attended East Derry’s one-room schoolhouse. As a boy he did odd jobs at the local airfield to learn about airplanes. An excellent student, Shepard won an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis. After graduation, Ensign Shepard served on the destroyer Cogswell during the closing months of World War II. At war’s end, he married Louise Brewer, whom he had met while attending the Naval Academy. Shepard was so eager to receive his wings and pilot’s license that he studied at a civilian flying school in his spare time while attending naval flight training at Corpus Christi, Texas and Pensacola, Florida. After receiving his wings, he served with the 42nd Fighter Squadron for several tours of duty aboard aircraft carriers in the Mediterranean.

In 1950, Shepard entered the U.S. Navy Test Pilot School in Patuxent, Maryland. After qualifying as a test pilot, he tested high-altitude aircraft and in-flight fueling systems, and made some of the first landings on angled carrier decks. He served as operations officer of the 193rd Fighter Squadron on two tours of the Western Pacific, and as an instructor at the Navy Test Pilot School. After graduation from the Naval War College at Newport, Rhode Island in 1958, Alan Shepard became aircraft readiness officer on the staff of the Commander in Chief of the Atlantic Fleet.

In 1959, the newly created National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) invited 110 top test pilots to volunteer for the manned space flight program. Of the original 110, Shepard was among the seven chosen for Project Mercury and presented to the public at a press conference on April 8, 1959. The other six were Malcolm (Scott) Carpenter, Leroy Cooper, John Glenn, Virgil (Gus) Grissom, Walter (Wally) Schirra and Donald (Deke) Slayton.

These seven were subjected to an unprecedented and grueling training in the sciences and in physical endurance. Every conceivable situation the men would encounter in space travel was studied and, when possible, simulated with training devices. Of the seven Mercury astronauts, Shepard was chosen for the first American manned mission into space. On April 15, 1961, only a few weeks before Shepard’s flight, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to reach outer space. Gagarin’s flight took him into orbit around the earth.

Shepard’s flight, on May 5, was still a history-making event. Whereas Gagarin had been only a passenger in his vehicle, Shepard was able to maneuver the Freedom 7 space capsule himself. While the Soviet mission was veiled in secrecy, Shepard’s flight, return from space, splashdown at sea, and recovery by helicopter to a waiting aircraft carrier were seen on live television by millions around the world. On his return, Shepard was honored with parades in Washington, New York and Los Angeles.

In the subsequent Mercury missions of Virgil Grissom and John Glenn, the U.S. space program would quickly meet and then surpass the achievements of the Soviet one. Shepard himself moved on to the next stage of the space program: Project Gemini.

Shepard was scheduled to command the first Gemini mission when he was diagnosed with an inner ear disturbance affecting his equilibrium. This disturbance kept him out of space for the next six years. He remained with NASA as chief of the astronaut office, but could only sit and watch as younger astronauts of Project Apollo prepared for travel to the moon. Tragedy struck the space program when a launch pad fire destroyed Apollo I, taking the lives of three astronauts, including Shepard’s Project Mercury comrade, Gus Grissom.

By 1968, an operation had restored Shepard’s equilibrium and he volunteered for a lunar mission, but Shepard remained earthbound, while Apollo XI and XII successfully landed men on the moon. Apollo XIII, which Shepard had hoped to lead himself, was forced to turn back in mid-course. In 1971, 47-year-old Alan Shepard, the oldest astronaut in the program, was finally tapped to lead the Apollo XIV mission to the moon.

Millions watched the live color broadcast of the mission, and few who saw it will ever forget the sight of Shepard and Edgar Mitchell bouncing around in the low-gravity environment, or of Shepard batting golf balls into the lunar distance before boarding the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM) to return to the craft orbiting above. Once again, Shepard returned from space to a hero’s welcome. He was promoted to Admiral before finally retiring from the Navy and from NASA.

Until 1961, space travel was only the fantasy of science fiction writers. In that year, fantasy became reality as the United States and the Soviet Union both launched men into space. On May 5 of that year, a Redstone rocket launched America’s first astronaut, Alan Shepard, beyond the earth’s atmosphere, into space.

Shepard’s mission made him a national hero and put to rest any fears that the United States would be left behind in the space race. Shepard, a former Navy test pilot, returned to space ten years later as commander of Apollo XIV, which he led successfully to the moon and back.

When America’s space program began in a blaze of publicity, the names of the first seven astronauts were known to almost every American. Today, many Americans take the missions of the Space Shuttle for granted, and few of our astronauts become household names. But of all the brave men and women who have led our country into the Space Age, one name still stands alone: that of Alan Shepard, the first American in space.

Admiral Shepard, the expression “The Right Stuff” has become part of our vocabulary. Maybe you and the others in the program have come to hate it, but what is the right stuff? What does it take to be an astronaut, to do what you’ve done?

Alan Shepard: I think first of all you have to be there for the right reason. You have to be there not for the fame and glory and recognition and being a page in a history book, but you have to be there because you believe your talent and ability can be applied effectively to operation of the spacecraft. Whether you are an astronomer or a life scientist, geophysicist, or a pilot, you’ve got to be there because you believe you are good in your field, and you can contribute, not because you are going to get a lot of fame or whatever when you get back. So that motive has to be there to start with.

And you have to be a fairly dedicated, objective individual, recognize that it is going to be dangerous, and you are going to spend your time practicing what to do if things go wrong.

You take that initial attitude of believing you can do it, and you build a lot of confidence, because — particularly in the simulators — if you respond to two or three horrible emergencies during the course of a morning, and do that day in and day out for weeks and months, it’s a tremendous confidence-builder. Some people could probably say it’s brainwashing in its best form. But there is a total confidence at the time of launch, because of the initial attitude, and because of the training philosophies — coping with contingencies.

NASA had a few mishaps with their first test firings, didn’t they? You couldn’t have been 100 percent sure that this Mercury spacecraft was going to work when you stepped into it that day.

Alan Shepard: That’s very true.

I think all of us certainly believed the statistics, which said that probably 88 percent chance of mission success and maybe 96 percent chance of survival. And we were willing to take those odds. But we wanted to be sure that if there were any failures in the machine that the man was going to be there to take over. And to correct it. And I think that still is true of this business — which is basically research and development — that you probably spend more time in planning and training and designing for things to go wrong, and how you cope with them, than you do for things to go right.

Admiral Shepard, on the morning you got into Freedom 7, took off, and became the first American in space, what were you experiencing, what were you feeling?

Alan Shepard: I think I ran the whole gamut of emotions. I woke up an hour before I was supposed to, and started going over the mental checklist: where do I go from here, what do I do? I don’t remember eating anything at all, just going through the physical, getting into the suit. We practiced that so much, it was all rote. We practiced that so much that I was ready for that.

The excitement really didn’t start to build until the trailer — which was carrying me, with a space suit with ventilation and all that sort of stuff — pulled up to the launch pad. I walked out, and looked at that huge rocket, the Redstone rocket, for the first time. Of course it’s not huge by today’s standards, but it seemed pretty big then. And I thought, well now, there is that little rascal, and I’m going to get up on top and fly that thing. And you know, pilots always go out to the airplanes and kick the tires before they fly. Nobody would let me get near the rocket to kick the fins, but I kind of walked around and thought, well, I’ll take a good look at it, because I’ll never see that part of the machine again. And then the excitement started building, I think, at that point.

After I was strapped in and ready to go, we had to hold, because we had to change a generator in the Redstone rocket.

I had a chance to sit back and relax a little bit, and again go through the process of “what do I do” for the first few minutes and first few seconds of the flight. And so I was really pretty relaxed by the time that lift-off finally occurred. I guess my pulse really wasn’t much over about 110 or so. I’ve forgotten exactly what it was, but everybody thought I was a pretty cool customer. At that point, you are basically thinking about, “What do I do if this goes wrong? What do I do if that goes wrong?” You know what critical things have to happen in sequence. The fact that you are accelerating with the thrust of the rocket is good, it’s very positive. You know that the rocket is doing its job and it’s doing it correctly. You’re just going over a checklist of one thing after the other. You’ve done it in the simulator so many times, you don’t have a real sense of being excited when the flight is going on. You’re excited before, but as soon as the liftoff occurs, you are busy doing what you have to do.

What were you thinking when they finally got you back to the carrier, and the world was waiting for you?

Alan Shepard: Of course I was delighted the flight was over, but I still had to worry about cleaning up inside the cabin, I had to worry about the hatch, how to get in the sling, and so on.

I remember just reaching the apex of the trajectory, when I was going to be in the middle of the weightlessness, and I was looking at the periscope, and all of a sudden I said, “You know, somebody is going to ask me how it feels to be weightless, so you better pay attention to how it feels to be weightless.” So I was going through the motions of flying, but at the same time trying to assess physiologically how I felt. Was I dizzy, or confused? And so on. And then I thought, “Well, somebody is going to ask me how the earth looks.” And so I looked down through the periscope — which was all that we had at that point — and made a few remarks, I think, on the tape, or perhaps on the radio. Then I had to get ready for reentry, so enough of that subjective thinking and back to the objectivity required to get this baby oriented to come back in. So you see, you could really go through a whole gamut of feelings, of nervousness and elation. Obviously at that point I was delighted. The rocket had worked perfectly, and all I had to do was survive the reentry forces. You do it all, in a flight like that, in a rather short period of time, just 16 minutes as a matter of fact.

Clearly one wasn’t enough. Did you know then that you wanted to do it again?

Alan Shepard: Oh, absolutely. I was delighted when I was assigned command of the first Gemini flight with Tom Stafford as my co-pilot, but it was shortly after that I developed a disorientation problem in my ear, and NASA grounded me. I was grounded for almost six years.

How did you feel about that?

Alan Shepard: I didn’t like it at all. This problem is called Meniere’s syndrome. It causes dizziness, nausea, lack of balance and so on. The prediction was that in some cases it was correctable. I said, “In my case it is going to be correctable.” A NASA guy said, “We like you, Shepard, you can be in charge of all the astronauts. You can’t fly, obviously, but you can fly with somebody else.” Whenever I flew, I always had to have somebody in the back seat of the airplane. So I was in administrative charge of the astronaut group, their training and so on. I could set them down, pat them on the head, and watch them fly. That was a little tough.

Then it was your turn, Admiral Shepard. Ten years after your first space flight, you find yourself on the moon.

Alan Shepard: I finally found a gent who corrected my ear problem surgically, and after NASA looked at me for perhaps a year, they decided that I was well enough to fly again. At that point I had some influence in crew selection, so I was able to work out a deal where I could fly on the lunar mission.

In the helicopter, flying back to the carrier, and seeing thousands of sailors on the deck of the carrier, being a Navy pilot, having made hundreds of carrier landings already, it was sort of like coming home. Except that there they were cheering for me. And that was probably the first moment of the flight when I felt the emotion of success — perhaps pride — in what I had done. And that was probably the first emotional moment in that whole flight.

What was it like to be up on the moon? You were 47 years old. Did anybody say you were too old to go to the moon?

Alan Shepard: Oh, yeah. We got all kinds of flak from the guys. In the first place, I hadn’t flown anything since 1961, and here it was ten years later, and the two guys with me had not flown before at all, so they called us the three rookies. We had to put up with that. And then the fact that everybody said, “That old man shouldn’t be up there on the moon.” As if it wasn’t enough of a challenge as it was, but that was part of the make-up of all those guys. They are still a pretty competitive group. So again, the gamut of emotions, the gamut of feelings, but instead of being 16 minutes in Freedom VII, it was stretched out to ten days in Apollo XIV. During the trans-lunar and the trans-earth phases there were almost three days when you really could relax. There were tasks of navigation and unstowing and getting ready and so on, but there was also some chance to look around, and see what the earth looked like, and really get used to zero gravity. Very pleasant moments.

You mean you never just looked around and said, “Here I am! I am on the moon!”

Alan Shepard: I did, but I really didn’t do that until we had landed and I was on the surface, and walked around a little bit, and then stopped and looked up.

The deal I tried to cut with NASA was to give me command of Apollo XIII. And they said, “Oh no. We can’t do that, you are too much of a political problem.” I said, “Well now, I’ve been training along with all these other guys, and I’m ready to go.” And they said, “Well, we know that, but the public doesn’t know that. So we will make a deal with you. We will let you command Apollo XIV if you will give us another crew for Apollo XIII.” So Slayton and I gave them another crew. And of course XIII was the one that had all the problems on the way up. A big explosion. You remember, the cliffhanger coming back. So apparently, I was getting some help from outside sources.

I was going about the little chores when I came to a rest period and looked up at the earth. The first time really seeing it in the black sky, the blue planet all by itself up there. That was an emotional moment. Some of the emotion was a result of having successfully arrived, a little sense of relief, but I think all of us, in our own ways, have expressed the same kind of feeling.

We had a couple of cliffhangers on Apollo XIV. In the first place, we tried to dock with the lunar module, and that didn’t work, so it could have been the end of the deal, but we finally got that organized. And then, the actual landing on the surface. We were supposed to get an update from the radar, we couldn’t go below 13,000 feet, and that came in only at the last minute. So there were a lot of little nervous things that kept you awake all the way down until you landed. But then you are there, and you say, “Well, we’re not going to take off for a couple of days, so let’s relax and enjoy it.”

I think all of us have expressed that. Maybe if people had a chance to see this, they wouldn’t be so parochial, they wouldn’t be so interested in their own particular territories. That will come in time, I think. Perhaps we could put the Security Council on the space station, and let them try to see where their little bailiwick is. To me and, I think, to all of us, it was a realization that our world is finite, it is small, it is fragile, and we need to start thinking about how to take care of it.

Seeing the earth, even though it is four times as large as the moon, but still it looks fragile. Still, it looks small. You think it’s pretty big when you’re back there among your friends and it’s 25,000 miles around, and so on. But from that distance you realize it is, in fact, fragile. It is, in fact, a small part only of our solar system, much less the rest of the universe.