My first six years in the business were hopeless. A lot of times I'd say, 'Why am I doing this?'

George Lucas was born in Modesto, California. The son of a stationery store owner, he was raised on a walnut ranch, and attended Modesto Junior College before enrolling in the University of Southern California film school. As a student at USC, Lucas made several short films, including Electronic Labyrinth: THX-1138: 4EB, which took first prize at the 1967-68 National Student Film Festival.

In 1967, Warner Brothers awarded him a scholarship to observe the filming of Finian’s Rainbow, directed by UCLA grad Francis Ford Coppola. The following year, Lucas worked as Coppola’s assistant on The Rain People and made a short film entitled Film Maker about the directing of the movie.

Lucas and Coppola shared a common vision of starting an independent film production company where a community of writers, producers, and directors could share ideas. In 1969, the two filmmakers moved to Northern California, where they founded American Zoetrope. The company’s first project was Lucas’s full-length version of THX:1138. In 1971, Coppola went into production for The Godfather, and Lucas formed his own company, Lucasfilm Ltd.

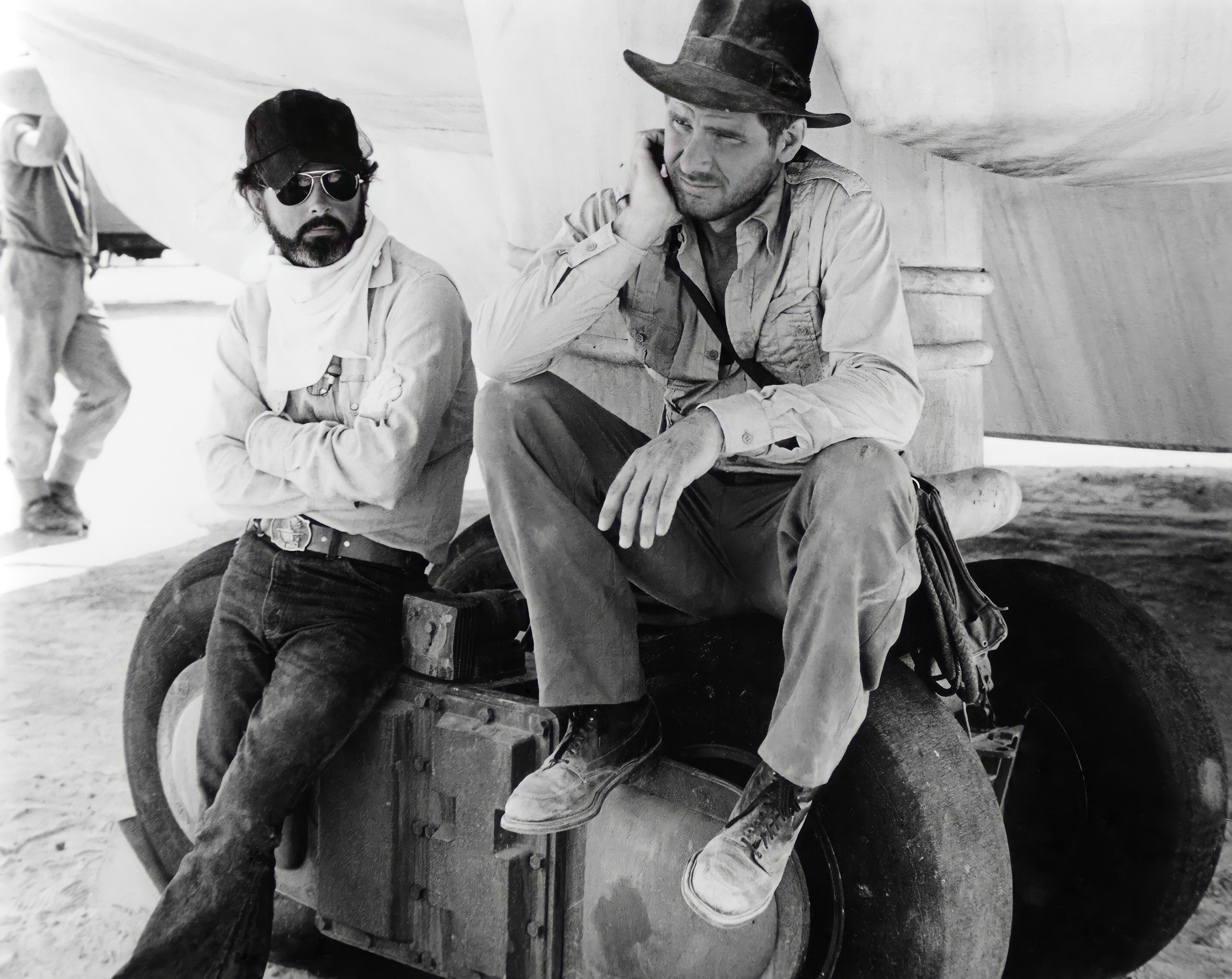

In 1973, Lucas co-wrote and directed American Graffiti. The film won the Golden Globe, the New York Film Critics’ and National Society of Film Critics’ awards, and garnered five Academy Award nominations. Four years later, Lucas wrote and directed Star Wars — a film which broke all box office records and earned seven Academy Awards. This intergalactic tale of good versus evil combined cutting-edge technology with good old-fashioned storytelling, and movies haven’t been the same since. Lucas went on to write the stories for The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, which he also executive-produced. In 1980, he was the executive producer of Raiders of the Lost Ark, directed by Steven Spielberg, which won five Academy Awards. He was also the co-executive producer and creator of the story for Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

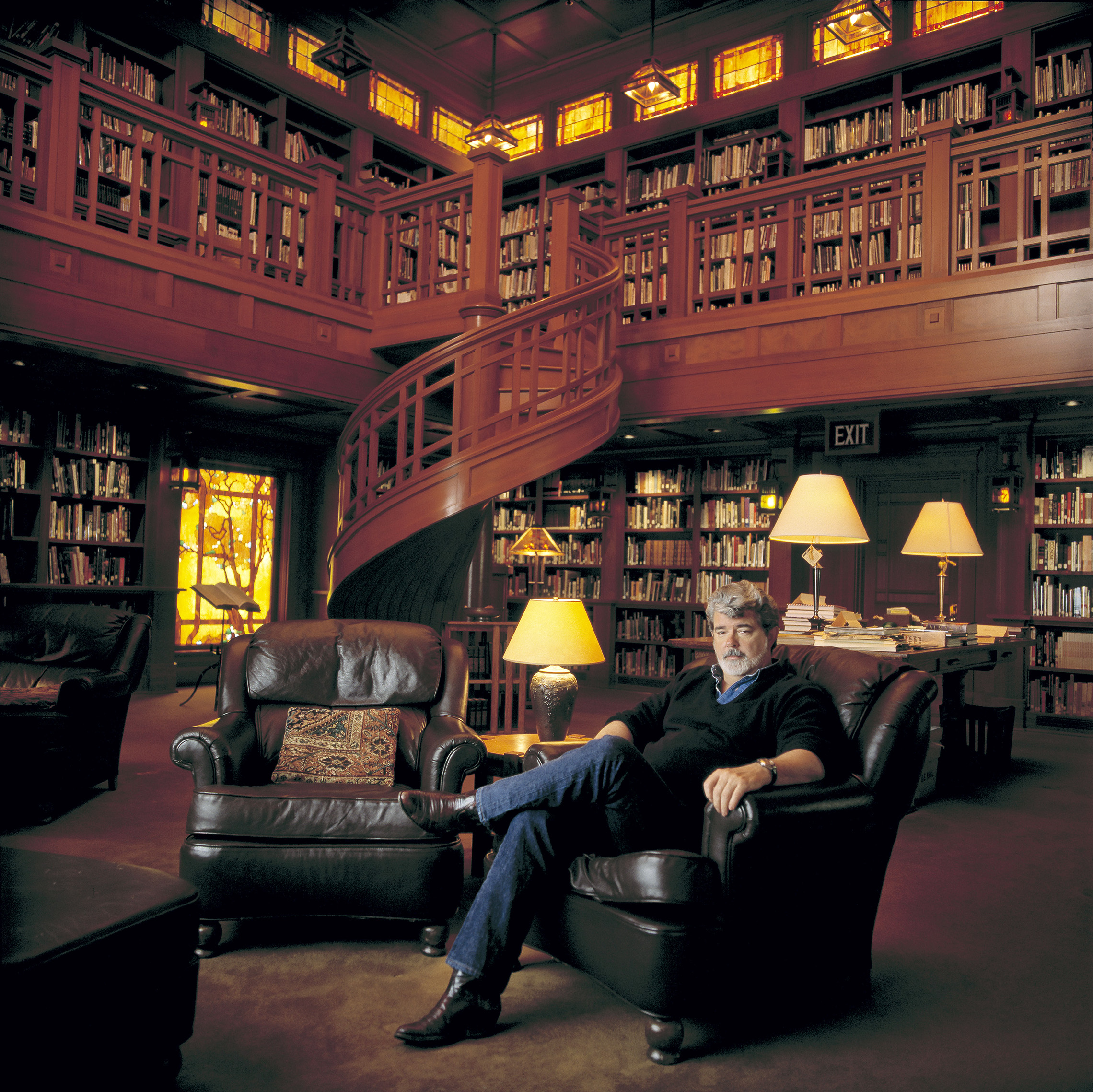

In the mid-1980s, Lucas concentrated on constructing Skywalker Ranch, a facility custom-designed by Lucas to accommodate the creative, technical, and administrative needs of his companies. Assembled, parcel by parcel, since 1978, the 4,700-acre Skywalker Ranch, located on the secluded Lucas Valley Road near Nicasio, California, cost George Lucas $100 million. Skywalker Ranch includes a 150,000-square-foot post-production and music recording facility as well as offices used for the research and development of new technologies in editing, audio, and multimedia. The Ranch, named after the Star Wars character Luke Skywalker, was completed in 1985.

In 1986, Lucas executive-produced Disneyland’s 3-D musical space adventure Captain Eo, which was directed by Francis Coppola and starred Michael Jackson. Captain Eo was shown in a theater uniquely designed by Lucas, Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), and Disney for the 17-minute spectacular. He was also the creator of Star Tours, combining the technology of a flight simulator with ILM special effects — making it the most popular attraction at Disneyland.

His next project was the adventure-fantasy film Willow. Based on an original story by Lucas, the film was directed by Ron Howard and executive-produced by Lucas. Willow was released in 1988. Also in 1988, Lucas executive-produced Tucker: The Man and His Dream, directed by Francis Coppola. The following year, Lucas served as executive producer for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

The company established by George Lucas in 1971 has today evolved into three entities. Lucas Digital Ltd. encompasses Industrial Light & Magic and Skywalker Sound, the award-winning visual effects, television commercial production, and audio post-production businesses. ILM has played a key role in over half of the top 15 box office hits of all time, and was honored in 1994 with an Academy Award for its achievements in Forrest Gump, which marked a technological breakthrough for the film industry.

LucasArts Entertainment Company is a leading international developer and publisher of entertainment software, having won critical acclaim with more than 100 industry awards for excellence, consistently charting in top ten lists of bestselling software. Lucasfilm Ltd. includes all of Lucas’s feature film and television production, and the business activities of Licensing and the THX Group. The THX division was created to define and maintain the highest quality standards in motion picture theaters and home theater systems.

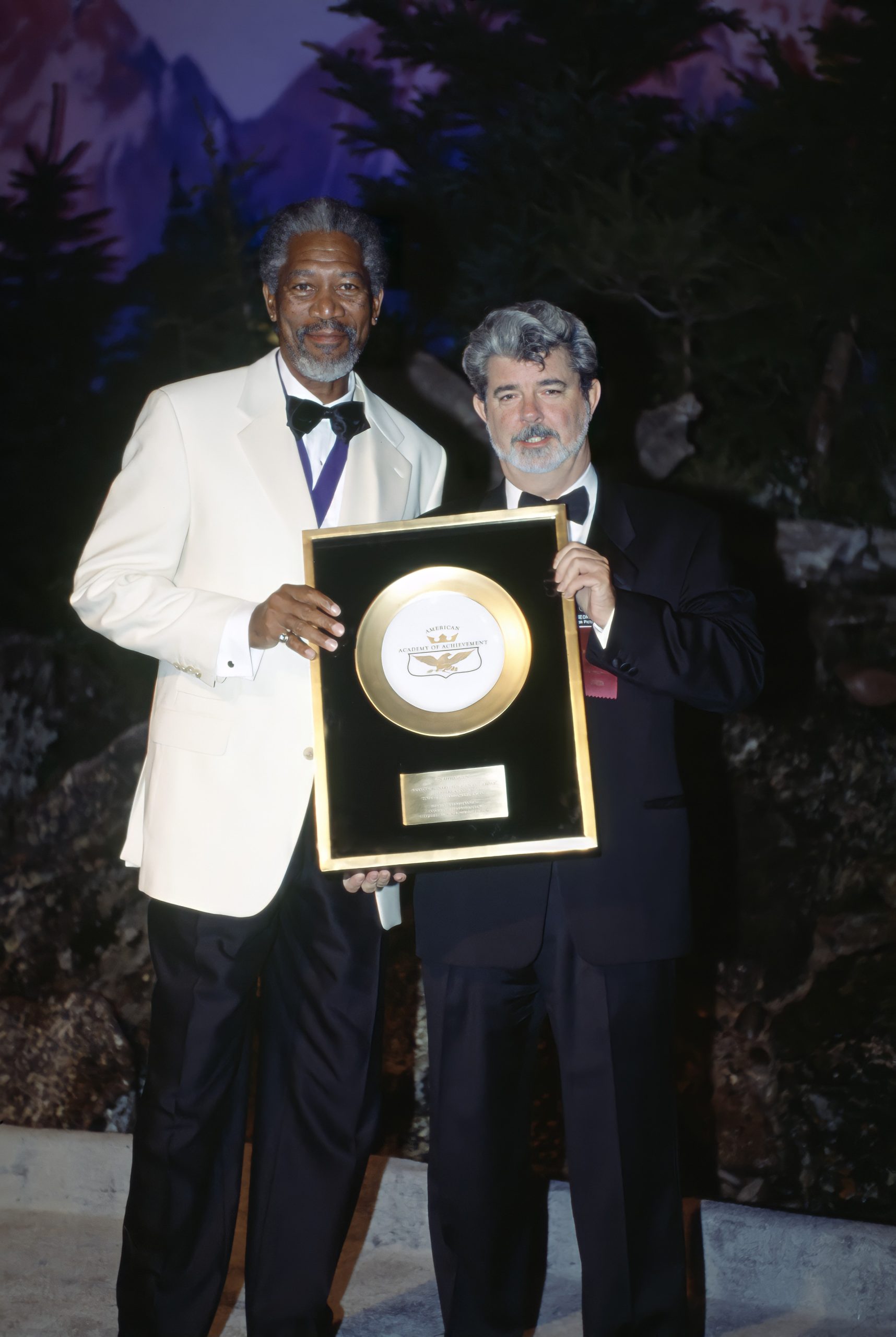

Additionally, George Lucas serves as Chairman of the Board of The George Lucas Educational Foundation, a tax-exempt charitable organization devoted to realizing the vision of a technology-enriched educational system of the future. In 1992, after numerous awards, George Lucas was honored with the Irving G. Thalberg Award by the Board of Governors of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

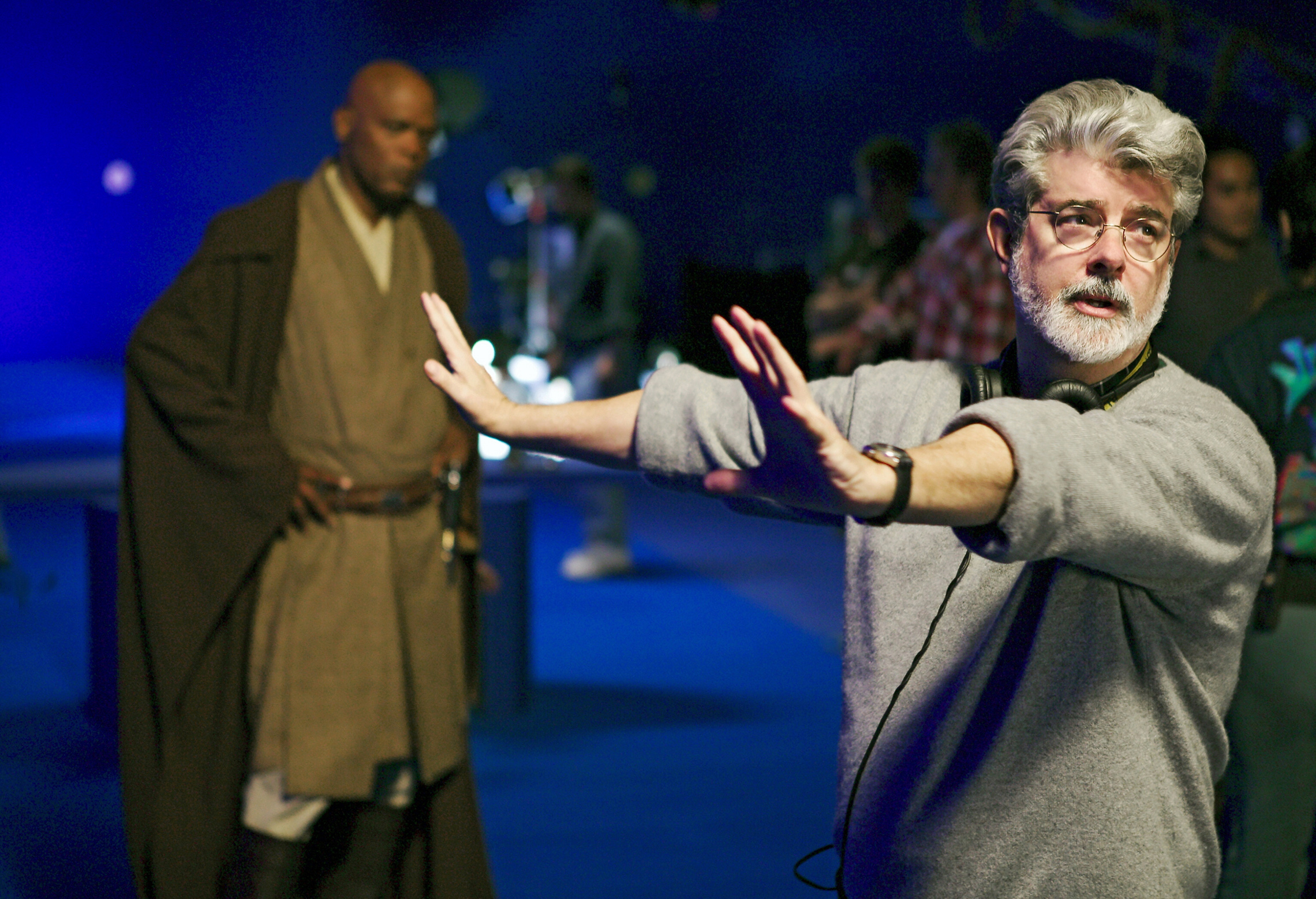

After a series of premiere screenings that raised $5.6 million for charity, the long-awaited first chapter in the Star Wars saga, The Phantom Menace opened in 1999, to record-breaking business across North America. It demolished the opening weekend box office records in 28 countries and ended the year with worldwide ticket sales of $922 million, making it the second-highest grossing film ever released. Subsequent chapters in the Star Wars saga, Attack of the Clones, and Revenge of the Sith, premiered in 2002 and 2005. Revenge of the Sith surpassed all previous box office records for a single day, for opening day, and for first weekend, taking in an estimated $303.2 million worldwide in its first four days.

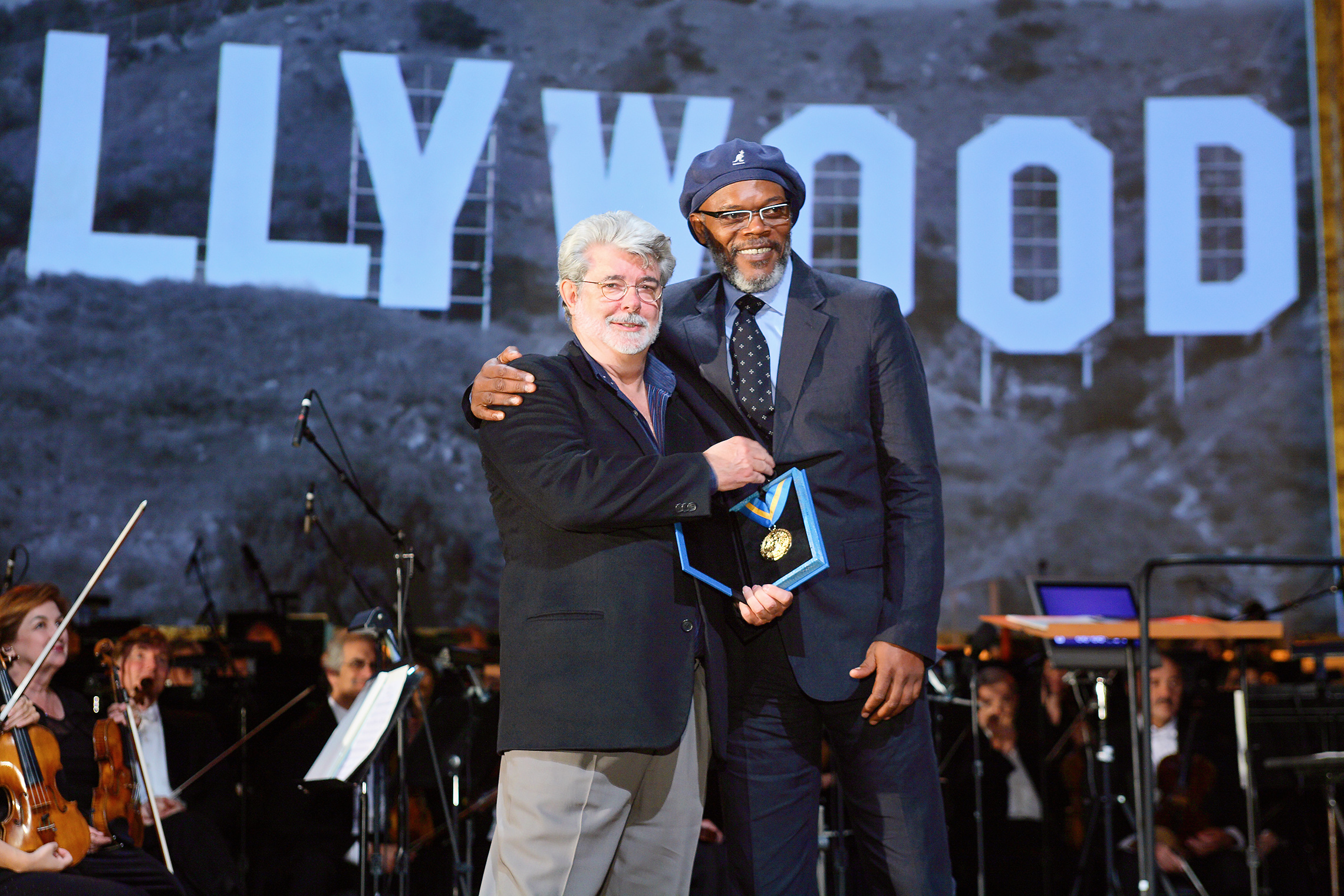

Since the 1980s, Lucasfilm has supported an array of innovative educational initiatives. In 2006, the Lucasfilm Foundation announced a $75 million donation to his alma mater, the University of Southern California, to construct state-of-the-art education buildings for the School of Cinematic Arts. In addition, Lucasfilm has recently given the film school an additional $100 million to establish an endowment. It is the largest single donation in USC history.

The following year, he founded the nonprofit Edutopia to drive innovation in education. In 2012, he sold Lucasfilm, Ltd. to the Walt Disney Company for a reported price of $4.05 billion. He has subscribed to The Giving Pledge, alongside Warren Buffet and Bill Gates, promising to give half his fortune to charity.

In June 2013, George Lucas married Mellody Hobson, President of Ariel Investments, in a ceremony at Skywalker Ranch. A second marriage for Lucas, the wedding was attended by his three adult children, and by many old friends, including Bill Moyers (who officiated), former Senator Bill Bradley, Francis Ford Coppola, Ron Howard, Quincy Jones, Steven Spielberg and Oprah Winfrey.

More recently, George Lucas is in the planning stages to develop the George Lucas Museum of Narrative Art at Exposition Park in Los Angeles. The Lucas Museum — designed by Ma Yansong, a Chinese architect known for free-flowing sculptural drama — will enable Lucas to share his extensive collection of art and film memorabilia with the public, including materials related to the production of his own films.

“If somebody gave me a hundred feet of film, I made a movie out of it.”

When George Lucas was attending USC Film School he didn’t even need a hundred feet. While still a student, he turned 32 feet of 16 millimeter film into a one-minute animated short that not only won awards at festivals nationwide, but set a new standard for animated films. He’s been making motion picture history ever since, creating many of the most popular films in motion picture history, including the phenomenally successful Star Wars and Indiana Jones films.

For over 40 years, George Lucas has served as Chairman of the Board of Lucasfilm Ltd., parent company of LucasArts Entertainment Company and Lucas Digital Ltd. Lucasfilm’s THX division has changed the way we hear films in movie theaters and at home. LucasArts Entertainment Company is a leading international developer of entertainment software. Lucas Digital Ltd., which includes Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) and Skywalker Sound, is the leading visual effects and post-production company in the industry. In 2012, he sold the company to The Walt Disney Company for a reported price of $4.05 billion.

No man comes as close to representing the art, technology, and business of the movie industry as George Lucas. His clarity of vision as storyteller and mythmaker, his zeal for innovation, and his leadership in forging a new relationship between entertainment and technology, has revolutionized the art of motion pictures.

You had a bad auto accident as a teenager. Do you think that changed the course of your life?

George Lucas: I’m not sure. I think about that sometimes.

I was a terrible student in high school, and the thing that the auto accident did — and it happened just as I graduated, so I was at this sort of crossroads — but it made me apply myself more, because I realized more than anything else what a thin thread we hang on in life, and I really wanted to make something out of my life. And I was in an accident that, in theory, no one could survive. So it was like, “Well, I’m here, and every day now is an extra day. I’ve been given an extra day, so I’ve got to make the most of it.” And then the next day I began with two extra days. And I’ve sort of — you can’t help in that situation but get into a mindset like that, which is you’ve been given this gift and every single day is a gift, and I wanted to make the most of it. Before, when I was in high school, I just sort of wandered around. I wanted to be a car mechanic, and I wanted to race cars, and the idea of trying to make something out of my life wasn’t really a priority. But the accident allowed me to apply myself at school. I got great grades. Eventually I got very excited about anthropology and about social sciences and psychology, and I was able to push my photography even further and eventually discovered film and film schools.

I decided to go to film school because I loved the idea of making films. I loved photography and everybody said it was a crazy thing to do because in those days nobody made it into the film business. I mean, unless you were related to somebody there was no way in. So everybody was thinking I was silly. “You’re never going to get a job.” But I wasn’t moved by that. I set the goal of getting through film school, and just then focused on getting to that level because I didn’t — you know, I didn’t know where I was going to go after that. I wanted to make documentary films, and eventually I got into the goal of — once I got to school — of making a film. One of the most telling things about film school is you’ve got a lot of students, in those days especially, it’s not quite so much today, but — wandering around saying, “Oh, I wish I could make a movie. I wish I could make a movie.” You know, “I can’t get in this class. I can’t get any this or that.” The first class I had was an animation class. It wasn’t a production class. I had a history class and an animation class. And, in the animation class they gave us one minute of film to put onto the animation camera to operate it, to see how you could move left, move right, make it go up and down. It was a test. You had certain requirements that you had to do. You had to make it go up and had to make it go down, and then the teacher would look at it and say, “Oh yes, you maneuvered this machine to do these things.” I took that one minute of film and made it into a movie, and it was a movie that won like, you know, 20 or 25 awards in every film festival in the world and kind of changed the whole animation department. Meanwhile all the other guys were going around saying, “Oh, I wish I could make a movie. I wish I was in a production class.” So then I got into another class, and it wasn’t really a production class, but I managed to get some film and I made a movie. And, I made lots of movies while in school while everybody else was running around saying, “Oh, I wish I could make a movie. I wish they’d give me some film.”

(George Lucas directed his first film while a 21-year-old student at USC film school in 1965. Look at Life, shot on 16-mm film, won awards for its innovative photo montage.)

You could actually go to school and learn how to make movies. Suddenly everything came together in one place. All my likes, everything I actually seemed to have talent for was right there. I said, “Hey, this is it. I can do this really well. I really love to do it.” And from then on I, you know, just took off, but before that I was kind of wandering, as I think a lot of students do.

Was the original Star Wars a tough sell? It seems obvious now, but what was it like to get that off the ground back in the 1970s?

George Lucas: I had a very, very difficult time with my first two pictures. And when I started working on Star Wars, my second film, American Graffiti had not come out yet. So, in the beginning it wasn’t something anybody was interested in, and I had taken it to a couple of studios, and they had turned it down. And then one studio executive saw American Graffiti and loved it, and I took him the proposal. He said, “You know, I don’t understand this, but I think you’re a great filmmaker, and I’m going to invest in you. I’m not going to invest in this project.” And that’s really how it got made.

Star Wars is so far removed from a film like American Graffiti.

George Lucas: Yeah, it was. All of my films have been very hard to understand at the script stage because they’re very different. At the time I did them they were not conventional. The executives could only think in terms of what they’d already seen. It’s hard for them to think in terms of what has never been done before.

Would you say your career has been marked by going against the conventional wisdom?

George Lucas: Yeah, and it’s made it considerably more difficult. It’s funny when you look back now, because everybody’s sort of copied those films. They’re so ingrained in the culture now, it’s almost impossible to think there was a point where those things were completely odd and unique.

The funny thing is, the two movies I directed that were my conventional movies were slight twists on very, very conventional movies, the kind that I loved when I was younger. One genre was the teenage hot rod movies made by American International Pictures, which were sort of the lowest rung of the movie ladder. The other was Republic Serials, Saturday morning serials from the ’30s, which were an ancient lowest rung on the ladder.

So I was taking the lowest genre that was available and then twisting it and making it into something completely different, something that was more mainstream in terms of the quality and acceptability of the modern movie-going audience. I think the prejudice against those films was really that they were cheap B movies; not that they were so out there.

Was there anything about you or your ideas that made it so difficult to get your first films made?

George Lucas: It was just my thinking. Those were the movies that I loved when I was younger.

I came from a very avant-garde documentary kind of filmmaking world. I like cinema verité, documentaries. I liked non-story, non-character tone poems that were being done in San Francisco at that time. And that’s the filmmaking that I was interested in. Francis Coppola, who was my mentor, sort of — he’s a writer and works with actors — stage director — and he said, “You’ve gotta learn how to do this.” And so I took him up on the challenge and wrote my own screenplays, learned to write and work with actors.

American Graffiti was really my first attempt at doing something mainstream, so to speak, and even it was so — one, it was in a genre that was looked down upon but I loved when I was a kid. It was about my life as I grew up, so I cared about it a lot. And then on top of it, it was in a style that was different from what everybody was used to. It was intercutting four stories that didn’t relate to each other, which nobody had really done before. Now it’s sort of the standard fare for television. And it had music all the way through it; not just the score but actual songs from the period, and that is something that nobody had done before. And they just sort of described it as a musical montage with no characters and no story, and so it was very, very hard to get that off the ground, and on top of that it was a B movie. I almost got it set up at American International Pictures, where they liked doing those kinds of movies but it was too strange for them in terms of the style. And Star Wars was kind of the same situation where it was a genre they weren’t that interested in. Science fiction was not something that did well at the box office. It dealt with robots and Wookies and things that — generally most people — they couldn’t read it and say, “I understand what this is all about.” They just were completely confused by it. And really on top of that, it was aimed at being a film for young people, and most of the studios said, “Look, that’s Disney’s. Disney does that. The rest of us can’t do that, so we don’t want to get into that area.” So I had so many strikes against me when I did that. I was lucky that I found a studio executive that just believed in me as a filmmaker and just disregarded the material itself.

In these groundbreaking circumstances, were you afflicted with any self-doubts, fear of failure?

George Lucas: Whenever you’re making a movie, especially when you’re writing, you always have self-doubts. I did the first location shooting in Tunisia. I didn’t get everything shot, but I had to get out of there in ten days regardless. What I had shot was the very beginning of the movie, and I was very worried about the creative quality of it. I just didn’t know.

I was working with an editor I hadn’t worked with before — I started out as an editor — I was working with a British editor and the scenes would come back, and I’d go on the weekends and look at the scenes with the editor, and they just weren’t working. And I was very down about the whole situation. So I went in myself on Sundays and started re-cutting the movie. The editing wasn’t obviously bad but it just wasn’t working. I couldn’t quite figure out what was going on. I mean it was either I was doing a terrible job directing this thing, or something else. As I started to cut the film together, I realized that I was making cuts that were, you know, a foot away from where the editor had been making them. And I had been using the same takes that I’d given him, but I was just slightly moving it ever so slightly in one direction, and it suddenly clicked and it started working, which was a great relief to me because up to that point I was feeling very desperate about the whole situation.

When the going gets rough, how do you deal with feelings of desperation?

George Lucas: I’ve had this quite a bit in my career actually. You simply have to put one foot in front of the other and keep going. Put blinders on and plow right ahead.

When I was doing American Graffiti I was still struggling with my “I don’t want to be a writer” syndrome. I had some good friends of mine that I wanted to write the screenplay, but it took me like two years just to get the money to do a screenplay. And I got a little tiny amount of money and — which I had to go actually to the Cannes Film Festival to get on my own. So finally I got this money. I called back and I said, you know, “I got the money. We can start working on the screenplay.” And they said, “Oh, we don’t want to do that now. We’ve got our own low-budget picture off the ground and we can’t write it.” I said, “Oh no.” I said, “What am I going to do? I am in Europe and I’m not going to be back for like three months and I want to get this thing off the ground.” So they recommended another student from school that I knew pretty well. I had a story treatment that laid out the entire story scene by scene, so I called him over the phone from London and I said, “Do you want to do this?” And he said, “Okay.” The person I was working with at that time as a producer made a deal with him for the whole money because there wasn’t very much. It was so tiny that he could only get him to do it for the whole amount of money. When I came back from England, the screenplay was a completely different screenplay from the story treatment. It was more like Hot Rods to Hell. It was very fantasy-like, with playing chicken and things that kids didn’t really do. I wanted something that was more like the way I grew up. So I took that and I said, “Okay. Now here I am. I’ve got a deal to turn in a screenplay. I’ve got a screenplay that is just not the kind of screenplay I want at all and I have no money.” And, I spent the very last money I had saved up to go to Europe to make the deal, so I had nothing. That was a very dark period for me so I sat down myself and wrote the screenplay.

And the most difficult part was that during the writing of the screenplay…

I kept getting phone calls from producers saying, “I hear you’re great.” I had made a film called THX, which had no story and no character really. It was kind of an avant-garde film. And so I had all these producers calling me saying, “I hear you’re really good at material that doesn’t have a story. I’ve got a record album I want you to make into a movie.” Things like that. And they were offering me a lot of money and — but they were terrible projects. And so I had to constantly turn down vast sums of money while I was starving, writing a screenplay for free that I didn’t like to write because I hated writing. But, I did finish it. I did write the screenplay and eventually I got a deal to make the movie. And then after I finally got that, then my friends came back in and did a rewrite on it, but it was a very dark period, and I could have very easily just taken the money and gone off and done one of these really terrible movies. I don’t know what that would have done for my career, but you know, when the times are hard like that you simply have to say, “This is what I want to do. I want to make my movie. I don’t want to take the money.” And you just walk forward, step by step and get through it somehow. And I got through. It actually only took me about three weeks to write that script. I just every day would sit down at eight o’clock in the morning and I’d write until about eight o’clock at night. And I just said, “I’m going to finish this, as painful as it is, and I’m going to ignore these phone calls of lure of riches and get through this.” And somehow I did it.