What more powerful form of study of mankind could there be than to read our own instruction book?

Francis Collins grew up on a small farm in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. His father, in addition to raising cows and sheep, taught at a nearby women’s college. His mother, a playwright, educated him at home until the sixth grade. When Collins graduated from high school at age 16, he was determined to become a chemist. At the time, he had no interest in biology, which he considered chaotic and unpredictable. At the University of Virginia, he continued to avoid biology, preferring to concentrate on chemistry and physics. After graduating with honors from the University of Virginia, he began working toward a doctorate in physical chemistry at Yale University. At Yale, he took a course in biochemistry, and first encountered DNA and RNA, the molecules that carry the code of life.

Fascinated by the emerging revolution in genetic science, Collins began to reconsider his career choice, and search for a way to apply his scientific education for the immediate benefit of his fellow human beings. While still completing his doctoral dissertation in physical chemistry, Collins enrolled in medical school at the University of North Carolina, and was introduced to the field of medical genetics. At last he had found the field that would allow him to combine his passion for research with his humanitarian convictions.

After completing his residency in internal medicine in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, he returned to Yale for a fellowship in human genetics. He later joined the faculty of the University of Michigan and swiftly moved through the academic ranks. At Yale and Michigan, he developed methods to cross large strands of DNA to identify abnormal genes. This approach, which he called “positional cloning,” allows the identification of the genes responsible for many disorders.

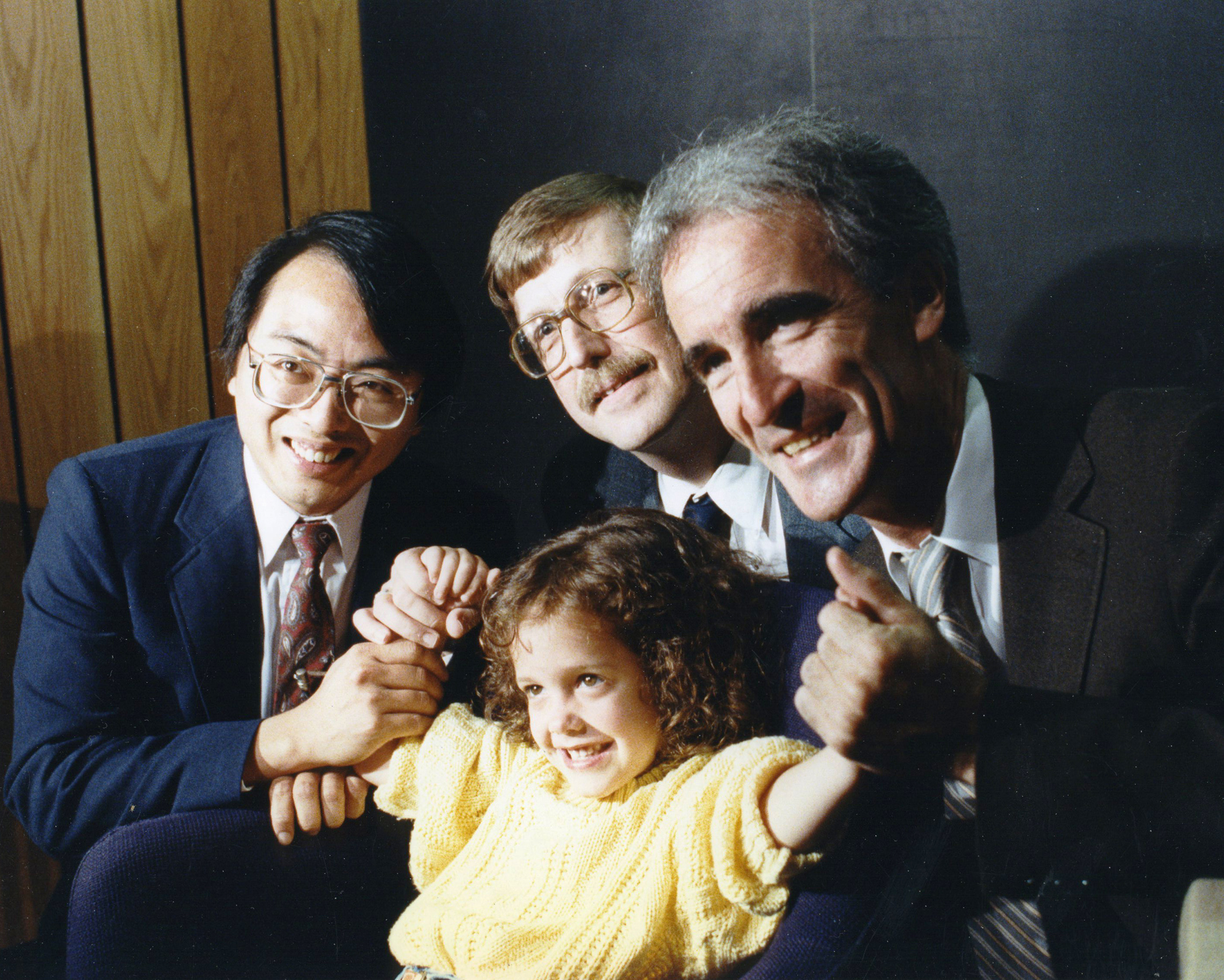

Together with Lap-Chee Tsui and Jack Riordan of the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada, his research team identified the gene for cystic fibrosis in 1989. That was followed by his group’s identification of the neurofibromatosis gene in 1990, and in 1993, “after the longest and most frustrating search in the annals of molecular biology,” Dr. Collins and his fellow genetic researchers located the defective gene that causes Huntington’s disease. Huntington’s disease is an incurable hereditary brain disorder that results in the death of brain cells.

Francis Collins has received numerous national and international awards for his research, and is a member of the Institute of Medicine and the National Academy of Sciences. His own laboratory remains active, studying the molecular genetics of diseases including adult-onset diabetes and the premature aging disorder known as progeria.

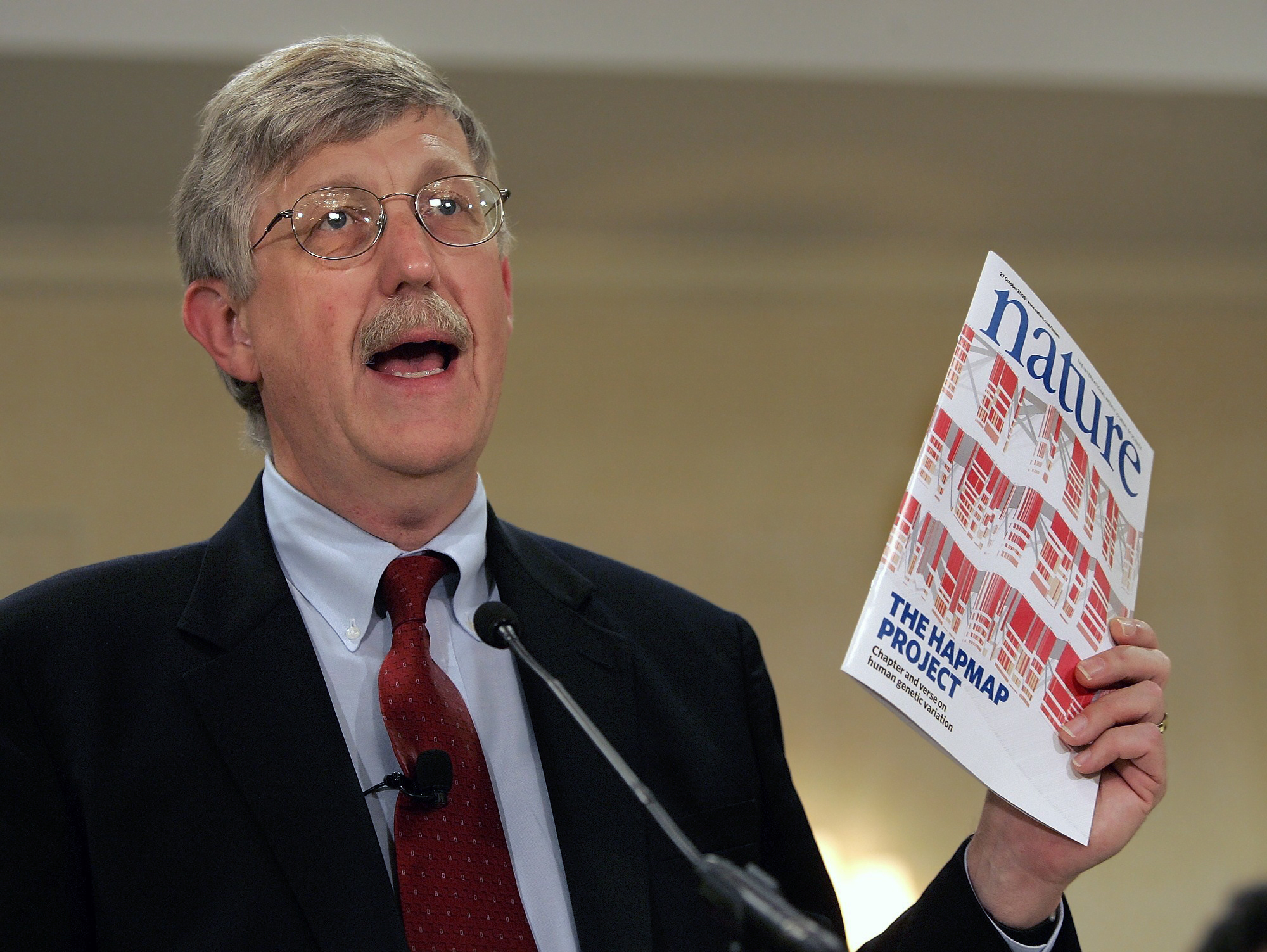

Dr. Collins accepted an invitation in 1993 to succeed James Watson as director of the National Center for Human Genome Research at the National Institutes of Health. In this role, Collins oversaw a 15-year multibillion-dollar effort to locate and map every gene in human DNA by the year 2005. Many consider this the most important undertaking in the history of science. Collins kept the project ahead of schedule and under budget. In June 2000, the Center had achieved a first rough draft of the human genome. By April 2003, Dr. Collins could announce the completion of the entire human genome sequence. As we learn the precise function of every gene, new discoveries yield incalculable benefits in the fight against birth defects and hereditary disease.

Francis Collins has written a number of books on science, medicine and religion, including the New York Times bestseller The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief. In the book, Dr. Collins advocates theistic evolution. He raises arguments for the idea of God from biology, astrophysics, psychology and other disciplines. Dr. Collins cites many famous thinkers, most particularly, C.S. Lewis, as well as Saint Augustine, Stephen Hawking and Charles Darwin. In The Language of God, Dr. Collins recounts how he accepted Christ as his Savior in 1978 and has been a devout Christian ever since. “The God of the Bible is also the God of the genome,” Dr. Collins writes. “He can be worshipped in the cathedral and in the laboratory.” Francis Collins is also the founder of the BioLogos Foundation, a group that fosters discussions about the intersection of Christianity and science.

In 2007, Dr. Collins was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. The award citation read, in part, “This monumental advance in scientific knowledge has begun to unlock some of the great mysteries of human life and has created the potential to develop treatments and cures for some of the most serious diseases. The United States honors Francis Collins for his efforts to decode human DNA and improve human health.” In August 2008, Dr. Collins stepped down, after 15 years as Director of the National Center for Human Genome Research. A little less than a year later, President Barack Obama chose him to serve as director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). A part of the Department of Health and Human Services, NIH is the primary federal agency for conducting and supporting medical research. As director of NIH, Francis Collins is responsible for 27 separate institutes and research centers, providing leadership and financial support to researchers in every state and throughout the world.

The National Institutes of Health, based in Bethesda, Maryland, has an annual budget of more than $30 billion for medical research. The NIH supports a wide range of scientists, including 300,000 researchers at more than 2,500 universities across the globe. The NIH is the largest public funder of clinical trials in the United States, annually providing $3 billion. Clinical trials are the component of biomedical research most directly connected to changes in medical practice, ranging from the potential human application of innovative laboratory findings to the treatments and preventive interventions in clinical care. The NIH has launched a multifaceted effort to improve the quality and efficiency of clinical trials. In 2015 — under the leadership of Dr. Francis Collins — the NIH initiated a plan to study the DNA and medical histories of one million American volunteers. Dr. Collins said the Precision Medicine Initiative Cohort Program, now named All Of Us, “has the potential to truly transform the practice of medicine” and predicted that understanding individual differences will allow doctors to better prevent and treat illness. This landmark initiative will help pinpoint links between environmental exposure, lifestyle, genetic variation and disease so that doctors can use all of this information, including individual genome sequences, to prescribe custom treatments for cancer, diabetes and heart disease.

In 2020, Dr. Collins was awarded the Templeton Prize, presented annually to an individual whose achievements advance the philanthropic vision of Sir John Templeton: “harnessing the power of the sciences to explore the deepest questions of the universe and humankind’s place and purpose within it.” In making the award, valued at £1.1 million (roughly $1,353,000), the John Templeton Foundation noted that Dr. Collins, “…throughout his career has advocated for the integration of faith and reason.” Citing his book, The Language of God, it said, “Collins has demonstrated how religious faith can motivate and inspire rigorous scientific research.”

Francis Collins continued to serve as NIH Director through the administration of President Donald Trump, steering the institutes through the COVID-19 pandemic that struck the world in 2020. The following year, incoming President Joseph Biden announced that Dr. Collins would continue to serve as NIH Director in the new administration.

On October 5, 2021, Dr. Collins announced he would step down as Director of the National Institutes of Health at the end of the year. However, he will continue to lead his research laboratory at the National Human Genome Research Institute. On February 16, 2022, President Joe Biden announced that Dr. Collins will perform the duties of Science Advisor to the President and Co-Chair of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology until permanent leadership is nominated and confirmed.

July 8, 2016: Dr. Francis Collins sings a duet with Mary Chapin Carpenter — Grammy Award-winning singer, songwriter and musician — at an American Academy of Achievement dinner and performance at the Jefferson Hotel in Washington, D.C.

“I concluded at the age of 15 or 16 that I had no interest in biology, or medicine, or any of those aspects of science that dealt with this messy thing called life. It just wasn’t organized, and I wanted to stick with the nice pristine sciences of chemistry and physics, where everything made sense.”

A few years later, this farm boy from Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley discovered the emerging field of DNA research and changed his whole direction in life. Already a graduate student with a wife and child, Francis Collins followed his graduate studies in chemistry and enrolled in medical school, determined to learn if the new discoveries in molecular biology could uncover the causes of hereditary illnesses.

Dr. Collins developed techniques to map and identify genes that cause human diseases including cystic fibrosis and Huntington’s disease. As Director of the National Center for Human Genome Research, he led one of the largest undertakings in the history of science. By 2003, this effort had decoded the entire human genome, the first essential step to unlocking the mysteries of human heredity. In July 2009, President Obama selected Dr. Collins to serve as Director of the National Institutes of Health, the federal government’s primary agency for conducting and supporting medical research. He has continued to serve in this position through the administration of President Trump and will continue to serve in the administration of President Biden.

(Dr. Francis Collins was interviewed twice by the Academy of Achievement — on May 23, 1998 at the Summit in Jackson Hole, Wyoming and on July 8, 2016 at the Academy headquarters in Washington, D.C. The following transcript draws on both interviews.)

When you were working on the Human Genome Project, you said that you hoped it would be even more significant than landing on the moon or splitting the atom. How has it stacked up?

Francis Collins: I think that prediction was correct. It is turning out to be the most significant organized scientific enterprise that humankind has mounted, at least up until now, to read our own instruction book. Sure, going to the moon was a huge deal. I’m a big fan of space science. Splitting the atom, all kinds of consequences, some of them a little worrisome but still very important for understanding really fundamentals about how matter is put together. But the Human Genome Project was about us. It was about all of us. It was understanding how it is that our DNA instruction book is capable of taking a single cell, which we all once were, and producing this incredibly complex, amazing, mysterious organism called a human being and how that can go really well, or how sometimes things go wrong and illness occurs. Now we are not done with that adventure, but the Human Genome Project basically said we’re seriously crossing this bridge. We’re into a territory where we know that fundamental information about our own instruction book. We’re never going back, and we did it, and life has changed for science immeasurably and for medicine bit by bit. We are seeing increasing consequences of that knowledge, and it’s only going to grow more profound with every passing year.

Will decoding the human genome have an impact in changing the lives of individual human beings?

Francis Collins: Knowing the human genome has already been changing individual lives, maybe particularly in the case of cancer. Cancer is a disease of the genome. It happens because of misspellings in that instruction book, some of them inherited, many of them acquired in a particular cell during life, maybe because of some toxic exposure, like a cigarette smoker. Maybe just because it’s really hard to copy your DNA and get it right every time. But if you want to understand cancer in the individual, you wanna know what happened. What were the particular glitches that occurred in that instruction book, and how could you use that to design a treatment for that individual that would not be the one-size-fits-all chemotherapy, which has saved many lives but is also very toxic and has failed in far too many circumstances, and change that into a truly rational approach that’s based upon that individual’s specific situation. That’s where we are headed, and I can tell you lots of amazing stories of people for whom that has been life-saving and who are not just living with cancer. They’re cured.

What kind of cancer?

Francis Collins: Lung cancer. Most people think of, “Oh, boy. If you had to have a cancer, don’t have that one,” and many people assume that’s mostly because of cigarettes, and a lot of it is, but there are lots of people who get lung cancer who have never smoked. Turns out, now that we have all of these genome sequences and genome tools, we’ve discovered that some fraction of them actually have a rearrangement of their DNA that brings together two genes that used to be a long way away and puts them together in a diabolical mix that produces a protein that makes cells grow when they should stop growing, and they keep on growing, and they spread, and that’s what cancer’s about. Knowing that led to the development of a targeted drug therapy with relatively few side effects, because you and I don’t have that abnormal protein. Only people with cancer do. The drug goes to that target, and it knocks it out, and there are people walking around today taking care of their grandkids or back at work who, a few years ago, you would have said, “There is no chance that person is gonna live more than a year.”

You went from the Human Genome Project to being Director of NIH. This is a huge organization — 5,000 doctors, 23,000 staff. How do you go about coordinating the efforts of so many people?

Francis Collins: One of the things I learned early on when I first came to NIH, asked to lead the Human Genome Project, was that you need to both have some kind of structure, so people aren’t just spinning off randomly in a direction that doesn’t add up to what you need to do, but other than that basic structure, you need to empower people.

You need to give them the opportunity to utilize their skills and talents, and you need to be comfortable surrounding yourself at every opportunity by people who are smarter than you are. And you also need to be comfortable surrounding yourself by people who are comfortable telling you, “Hey, you’re on the wrong tact here. You’re about to make a dumb mistake. I don’t agree with the decision you’ve just made.” The worst thing you could do in this situation is to have people around you who are afraid to confront you about a mistake you’re gonna make.

So I have lots of people around me who are not afraid at all, and it’s wonderful that way. So it’s a very open, honest interchange where people feel empowered to express their perspective, and when we get a team going, it lives on that basis, but everybody has to decide upfront that there’s a shared goal, and we will all fail unless all of us succeed, so we have to agree that we’re moving towards a common goal. And we can disagree, but ultimately we have to commit to that goal.

You work with thousands of scientists at NIH. Is there something they have in common?

Francis Collins: I think most scientists got into science partly out of curiosity and because it’s such fun to actually spend your time trying to solve mysteries, and sometimes you can’t even believe you get paid to do this, but underneath that there’s an altruism. There’s a desire to help people. Even if you’re working in a very obscure basic arena, I have yet to meet a scientist who does not have somewhere down in there a whole set of motivations, a desire to make the world a better place, to add knowledge to the universe, and ultimately to have that knowledge translated into something that will make life just a little better for somebody. So that’s a wonderful shared motivation, and when you get to a circumstance where maybe people are disagreeing a little bit about exactly what needs to be done, you can call upon them to remember what this is all about. This is not about making money, because most people in the academic arena or in the NIH arena are not there for the cash. It’s about trying to make the world a better place. We can all agree to that.

A lot of the public thinks of the scientist as a guy in a white coat doing tedious lab work. How do you improve that image in the public mind?

Francis Collins: Well, it is a lot of tedious lab work!

Francis Collins: Solving mysteries doesn’t just happen because you want to or because you designed this clever little experiment and it works the first time. I continue to run a research lab at NIH. I have ten people who work with me on diabetes and on aging, and as I could say has been true for my entire research career, about 95% of the experiments we do are total failures, and that’s because we’re out there on the leading edge of what’s possible, and most of the time it isn’t quite possible.

And you have to kind of get used to that and even take it, after you’ve developed a little maturity about it, as a badge of reality-check that you really are asking a hard problem. If your experiments are working all the time, must not be a very interesting problem. So a lot of science is very hard work, and yes, there’s a lot of disappointment, and that was tough for me when I first moved into experimental science, and I sort of attached my own sense of personal worth to whether the experiment had worked or not, and since most of the time it didn’t, I was beginning to wonder, “What’s wrong with me?”

And then I began to realize, “No, wait a minute. That’s just a sign that you’re doing something really hard and really important, and stick to it, and ultimately you might learn something.” And so when you have those moments — and they don’t come along all the time, where something does work and you get an insight into how life works or how disease happens that nobody else knew before, that is not a moment that you can possibly step away from without being affected, and that keeps you going, and that says, “Okay, I’m in it. I’m ready for the next one.”

Could you describe one of those moments in your own career?

Francis Collins: Well, as an assistant professor back then, at the University of Michigan, trying to apply what we would now consider pretty rudimentary tools, but they were very high-tech at the time, to discover causes of human diseases, a big part of my passion was to find the cause of cystic fibrosis. I had met that disease as a doctor, but as a researcher, I wanted to understand it because, as a doctor, there wasn’t much to say other than, “People get this terrible problem in their lungs and their digestive system, and they die young, and we don’t know why, other than it seems to be genetic.”

So we chased after that cause. I spent five years with a lab that was incredibly flat-out devoted to this, and yet we went down so many blind alleys. We had so many frustrating experiences where our technology just wasn’t up to the task. There was no genome project, so most of what we needed to know, we had to invent from scratch, and it was tedious, and it was full of errors all the time, and disappointments rained down upon us for five years.

And then the time came where on that fateful, rainy day in May 1989, we knew we had the answer, and it was almost hard to accept because when you’ve been burned a few times, you’re afraid to accept the answer as being correct, because maybe it will be wrong again by tomorrow, but this one was really compelling.

What actually happened on that day?

Francis Collins: So my lab at Michigan had worked on this disease for three years and made a little progress, but we were really struggling, and there was another lab in Toronto who had worked on it for five years, and they made some progress, but they were struggling. And we decided to pool our labs together.

Lap-Chee Tsui, who was the director of the Toronto lab, and I met and said, “You know, we don’t…” — it’s an example of what we’re talking about. “It’s not that this is about some grand personal triumph. It’s trying to make the world a better place. We gotta figure out the answer to this. Let’s just put our labs together. Maybe we can go faster.” And we did, and for that flat-out two years we worked intensively with a team in both places, and it was May, and we were both at a meeting, in one of those scientific meetings that one needs to go to. It wasn’t particularly about cystic fibrosis, but our labs were working night and day because we thought we were onto something.

We were staying in the dorms at Yale, because that’s where the meeting was, and my colleague had put a fax machine in his dorm room so that we could see the lab data from that day. Of course there was no e-mail, so it was all about fax. And after a very intense day at the meeting, we went back to his room, and here was all these fax sheets lying on the floor, and we picked them up, and there was a lot of data. And it wasn’t immediately clear what was there, but by the time you got to page seven or eight it was pretty clear that this one had to be right.

I knew then that we had identified the gene, which when misspelled caused this disease, and it was a gene nobody could have predicted, and it was a gene that looked like it might be susceptible to some kind of therapeutic intervention, maybe gene therapy, maybe drug therapy, but we’d been in the dark, and now the light had turned on, and that had to be the most significant step forward that cystic fibrosis research had ever seen, and had to, ultimately, lead to cures for this disease.

And here we are now, 27 years later, and those cures have happened for some of the people with the disease, not yet all of them, but — a long path from gene discovery to treatment, but we’re getting there.

What about cancer? There’s speculation that we’re on the brink of a cure.

We are, but let’s be clear. Cancer is hundreds of diseases, and the cures will come at a different pace for different individuals, depending on what their cancer has going on. Cancer is a remarkably individualized disorder. As soon as you start looking closely at the cancer cell you realize that almost every cancer is different from every other. So if you want to say, “Are we close to a cure?” — you have to say, “Okay, for which cancers, and for which people?”

We’ve already seen dramatic cures of some people who had cancers that you would have thought were almost certainly gonna be fatal and in the near future. People even talk about Lazarus situations where people who are really at death’s door encounter an opportunity to be part of a clinical trial and have that remarkable response. But unfortunately that’s still not true for some cancers — it’s particularly difficult.

Brain tumors, pancreatic cancer. We still don’t do very well in those situations, but we have ideas. Some of them are to identify what’s going on in that cancer and develop a drug that approaches that problem in a very specific lock-and-key way, and we have great successes there, particularly with some kinds of leukemia and lung cancer, but some of it is getting the immune system to get activated to do what the immune system is designed to do, to recognize something that’s not right, what’s a foreign cell — and a cancer is a foreign cell, and do something about that.

Ten years from now, how will we be treating cancer differently?

Francis Collins: Ten years from now, anybody who develops cancer will have that cancer very intensively examined, complete DNA sequence, analysis of what genes are on or off, what proteins are being produced, and then a decision will be made of the increasingly long menu of targeted therapies that are both specific and not very toxic, what’s the right choice for that person to have the best possible outcome, and it will probably not be a single drug, because we know single drugs for other things, like HIV, can give you a response, but you want a cure.

It’ll probably be a combination, and the success rate might also depend upon an immune therapy being part of that mix, and it should be very high. But more than that, ten years from now our screening for cancer will have changed dramatically. We will find cancers at a much earlier stage when they’re better treated, and many of us think that will happen again because of DNA studies.

Turns out cancer cells are kind of clunky, and they actually spill their DNA into the blood circulation at a low level, and so all of the things we do now to survey for cancer using imaging and various protein markers may very well go by the boards, and it will be a DNA test that maybe we’ll each have once a year that looks for little hints of cancer cell DNA floating around that would be a sign you’d better find out what’s here, and then we’ll have it early enough to have a much better chance of treating that kind of — early detection is going to be transformed in the next ten years.

Does that mean that fewer people will be suffering and dying of cancer?

Francis Collins: My absolute confidence is that we will reduce the mortality from cancer in the part of the world that has resources. My fervent hope and personal commitment is to be sure that that is not limited just to the countries that have those resources. So a big part of my own concern is that we figure out a way to make these kinds of interventions accessible, exportable, affordable, because I believe that every life matters, and if we celebrate accomplishments in the U.S. and a few other countries and see no advances in other parts of the world then we haven’t really done our job.

What can you tell us about CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats), the genome editing technique?

Francis Collins: CRISPR has transformed the whole field of biology in a breathtakingly short period of time because of the potential it offers, which is being realized every day, of being able to edit genes, being able to make changes in the genomes of lots of organisms, including humans, and a precision that none of us would have imagined possible even five years ago.

It’s this wonderful story about how studying the most obscure area of basic science, like why these particular microorganisms seem to have weird DNA sequences in their genomes and how that helps them fight off viruses that otherwise would attack them, I mean, who could possibly get interested in that? Well, people did, and in the process discovered this remarkable system of enzymes and RNAs that allow you, like a most precise kind of microsurgery, to go and find any place in a genome and cut it and repair it.

And that is breathtaking. My lab, like other labs, is using CRISPR-Cas to do all kinds of experiments that might have taken us years, and now we can do them in weeks. Of course the big concern is will we take this too far, and I think we should be talking about that, but for the most part, CRISPR is just an amazing experimental advance to allow us to understand how life works.

Your work affects millions of people, and involves matters of life and death. Has this influenced your own thinking about the meaning of life?

Francis Collins: Hm. Life has so many different levels that one could talk about in terms of meaning. As a scientist, I can reduce it down to this whole set of molecules and genes and proteins and how you go from being one cell to being you and me. At a much different level, sitting at the bedside of a patient who’s struggling with a terrible disease, life is so precious. Life is something we all want to hang on to, if we possibly can, and medicine is supposed to achieve that and yet sometimes falls short.

For me, as a person who also is a person of faith, life has other significance of a spiritual sort, but who we are as humans and what makes us able to interact with each other, to understand concepts like love that you can’t write an equation about, and even to have this hunger for a relationship with God, all of those things are part of what I think about it in a question like what is the meaning of life.

But I’m saying it rather badly compared to what other great sages have said down through the centuries, and we need to pay attention to them and read their words as well. Science should never imagine that we’re the ones who are going to answer all the questions. We can answer some really important questions about how things work, about nature. We’re not so good at why. We’re pretty good at how. I think the why questions are pretty important too. Why am I here?

Something that C.S. Lewis writes beautifully about — C.S. Lewis had a big influence on me in this spiritual realm — this sort of sense of longing. A longing for a knowledge that is just outside of our reach, a knowledge for a spiritual connection that you know must be really important because you feel the need for it but you’re not quite sure what it is you’re longing for. A longing to know the answer to is there a God, and what is that God like, and does God care about me, and should I be spending more time thinking about that? I think longing is, in many ways, the thing that drives all of us in whatever we do, a longing for a scientist to make a discovery, to know something that wasn’t known before, just to get your experiment to work, and when that is satisfied, even temporarily — because it’s always temporary, yeah, that longing has led you somewhere that feels pretty good. But there’s a certain part of human longing that we all know will never be fully satisfied while we’re walking around on this planet, a longing for something more eternal, more out of reach, more numinous, as some would say. A sense that it’s there, that it’s just a little bit out of our grasp, is not something that we can get past.