Around six years after you broke the sound barrier, you broke another big record in 1953. Tell us about the exploits with the X-1A.

Chuck Yeager: To go back a little bit, the Air Force, or military pilots, had never been allowed to do research flying. Research flying was always done by civilian pilots who worked as test pilots for the company that built the airplane. And the X-1 was the same way.

When the X-1 was finished in 1946, Bell Company test pilots, who were civilian, did the initial twenty-some flights on the airplane, for tremendous amounts of bonus money. And that’s the way the Air Force got its hands on the X-1 and put a military pilot such as myself in the cockpit. The civilian pilot wanted an exorbitant amount of money to take the airplane supersonic, or to try to take it supersonic. And when Bell Aircraft Company had a contract with him, he had a contract for bonus money, but he wanted it paid over a five-year period. Now see, all this money comes out of the Air Force’s pocket to support the test program. They paid for everything. So when he started delaying the program, in the spring of 1947, because he wasn’t getting the kind of money that he wanted out of Bell Aircraft Company, well the Air Force saw a marvelous opportunity. In fact, Colonel Boyd saw a marvelous opportunity. He said, “I’ll get my hands on the airplane, and we’ll let an Air Force pilot, who is much better qualified, because the Air Force test pilots fly every airplane that every company builds.” A civilian test pilot only flies that airplane which his company built. We were all combat veterans, not all of us, but most of the guys that came back, especially myself, were combat veterans. We could fly airplanes, obviously. And so that was the reason that we finally got an Air Force pilot in the X-1.

Now, 1953. Here Bell was right back into the same old routine. They had a civilian test pilot hired to fly the X-1A. The X-1A differed from the X-1. It was an airplane about seven feet longer, carried almost twice as much fuel, it had the same wing, same tail and the same engine and it was predicted that the airplane would go more than twice the speed of sound. Whereas the X-1, the fastest we could ever get it to go was about 1.5 mach number and you run out of fuel. So this Bell test pilot, he flew the X-1A some six flights. He never did get it even above the speed of sound because he had no experience in that kind of flying. I used to chase him in an F-86D, on his wing. You could see the shock waves on the airplane and the buffeting, which was normal, because we had gone through that sequence with the X-1. But the guy, because of a lack of experience and knowledge, never took the airplane above the speed of sound. And finally, he killed himself in an X-2, back at Bell Aircraft Company. They had it under a B-50 mother ship, and they were running some liquid oxygen top-off tests on the airplane. It exploded, blew the airplane and him out of the aircraft and killed him. So there sat the X-1A with Bell Aircraft Company with no pilot. And so they came to the Air Force. They said, “Okay, here is your airplane, it’s yours.” So they put me in the airplane to fly it.

Since I had been chasing him, I intimately knew the airplane, the systems, and it was basically the same as the old X-1, except we didn’t use high pressure nitrogen gas to do the work. We used hydrogen peroxide generators, turbine pumps and things like that. So on the first flight that I flew the X-1A, we were coming up on the fiftieth anniversary of the Wright Brothers’ flight, December 17, 1953. This was in October or November when the X-1A became my program. Jack Ridley and I sat down. Since we wanted to get the airplane out beyond mach two by December 17, we worked out a profile on how we can get the airplane as fast as it possibly would go. We worked out this profile of dropping out of the B-50 at 30,000 feet, firing off three of the four chambers on your rocket motor, accelerate out to .8 mach, then climb up to 45,000 feet, level out, fire off the fourth chamber so you got full power, take it out to about 1.1 through the speed of sound, then climb at supersonic speeds in about a 45-degree climb angle and at 60,000 feet you start leveling out. You become level at about 72,000 feet, and you hold it there at 72,000 feet, and accelerate like mad until you run out of fuel. And we looked at our figures, Jack and I, working up this profile. We knew we could get quite a bit above mach two, but we didn’t think that we would get out to two and one-half times the speed of sound. In fact, the Bell engineers said, “You better be careful above about 2.2 mach number because we really don’t know what we are getting into out here and no one else does either. We haven’t got any wind tunnel data, nothing has ever been out there before.”

And so, the first flight that I flew on the airplane, I was just practicing this profile, and also wanted to take it out to supersonic speeds. So I just cranked three chambers, ran it up, leveled out, and let it run out to about 1.3 mach number. And it flew just like the X-1 did. We lost the elevator effectiveness; I had to use the stabilizer to fly through mach 1. So then, I jettisoned the rest of the fuel; I came on down and landed. Then the second flight, three of four days later, I took the airplane on up to about 50,000 feet, kept it level and I got 1.5 mach, which was the fastest we’d ever had the old X-1, number one airplane. And then the third flight, a few days later, I took it on up to 1.9 mach, just under mach 2, at about 65,000 feet. And hey, it was really flying nice. I had a pressure suit on, in case you lose your canopy or if you lose your cockpit pressurization, you can stay alive with a pressure suit above 50,000 feet.

And on the fourth flight, I think it was on December 12, everything went beautiful. The drop was right on speed, and the chambers ignited when you flick the switch. The profile was beautiful. The only thing that happened, on the climb out, on all four chambers running and you’re really accelerating – you fly off of a little eight ball flight indicator for attitude reference. And, you have a pressure suite; you’ve got filament wires in the visor of your suite. You have to keep those hot to keep your visor from fogging up. I let the airplane get up a little bit steep. I was busy regulating the pressures in the chamber to get maximum thrust out of the engine, and I got the airplane just a little bit steep, probably pushing 65 degrees angle of attack rather than 45. As I went through 60,000 feet, it began to push the airplane over. There are a lot of things that happen to an airplane mechanically up there. You have liquid oxygen in a tank and, if go to zero G, flying the parabolic curve, at zero G that oxygen cavitates because there is nothing to hold it down in the bottom of the tank. And so you have to hold about a tenth of a G on the way over. I floated right on through 70,000 feet up to 80,000 feet, which was about 10,000 feet higher. I hung on, and I’m sitting there looking as the mach meter went up to about three. And as I went through something like 2.3 mach number, man, we were really smoking. We were picking up about 31 miles per hour, per second. And I watched this thing, and as we went through about 2.3 mach number, the airplane began to yaw. I said, man, something’s not right. I pushed on rudder to try to get the nose back, and nothing happened, the airplane just kept yawing. Then, the outside wing, because of dihedral effect, begins coming up. Next I’m cranking on full aileron and full rudder, and nothing happens. The airplane rolled, inverted, pitched up, and when that happened, the canopy busted on it. And when that happened, the suit inflated. Then the airplane really got wound up in some snap rolls, and the data shows that we had a rotational rate of about 580 degrees per second, which is twice per second going around. And you get exposed to a lot of high Gs. Like we were getting 9 Gs positive, 2 Gs side load, 3 negative, 2 side load, 9 positive. You go through two cycles of each per second. And you really don’t know what’s going on other than, I figured that either the tail had come off the airplane or something had happened. So, I just pretty well rode it. You know, you see sky and ground flashing. You get rattled, but you never become unconscious. I just hung on to the airplane pretty well. The first thing that I recognized was that I came out with a tremendous inverted, negative G flat spin. Well, we spin airplanes all the time. So you recognize a characteristic airplane flat spinning, inverted. You can get it out by putting the aileron with the spin direction, and using the rudder to stop it, and make it fall through. And it did. And then the airplane flipped into a normal spin, which is an upright spin. I say normal because that’s the way normally an airplane spins, upright. It flipped into a normal spin, and I just popped the nose out with the elevator and opposite rudder to stop it and recover it. And when this happened, I was down; I was about fifty miles from Rogers Dry Lake, at 25,000 feet. I was sitting there looking and the pressurization was gone out of the cockpit. Part of the canopy was gone, my suit was inflated, it had kept me alive. I looked around; I finally spotted the lakebed and turned toward it. And from the time the airplane yawed and ran out of fuel up there at 2.5 mach number, till I popped it out of the spin at 25,000 feet, was only 51 seconds. But 51 seconds, if you will look at your watch, is a long time. And so I just glided on back to the base, and landed. And that’s the last flight I made in the airplane. And we never did take it above about mach two anymore.

Isn’t there a tape of what you went through on that?

Chuck Yeager: Yes. We didn’t say anything, obviously, because you are wasting your time if you talk. The object is to try to survive, and basically I think the tape started, it covers the whole flight until I get all four chambers on and then smoke out. Then we didn’t say anything until the end of the tumble when I called Jack Ridley and told him that I had a problem and didn’t know if I could get the airplane back to base. It was a big job for them to find me because I was way high and they were chasing me in F-86s. But, I just brought the airplane down and landed it on the lakebed, they changed the canopy, and the airplane was ready to fly again.

But we never did take it out to that speed because the airplane had a very small tail on it, horizontal stabilizer and vertical stabilizer, rudder and elevator. When we went through about 2.2 mach number, the conical shock wave that forms on the nose of the airplane comes down as you go faster. It’s not flat, it’s conical in shape and when we got out to about 2.3 or 2.4 mach number, this shock wave is down to where it’s almost at the tip of the horizontal and vertical stabilizer. And when that thing coned in like that, we lost stability on all three axes of the airplane. It just flew apart. Fortunately the airplane was stressed for 18 Gs positive or negative, so we didn’t break it up. Just through pure instinct, you sort of recover from the inverted spin into a normal spin, and bring it back and land it.

At the end of that flight, weren’t you kind of joking about it?

Chuck Yeager: Well, you always do. Basically, some smart-assed remark or something about a structural demonstration. But you are relieved that the thing didn’t kill you. That’s about what it turns out to be.

And the funny thing about it was that was a full day for me. I got up about four o’clock. I was hunting ducks in the early morning, came over and was briefed on the flight, looked over the airplane and then flew it.

I think I got home about 4:30, and Glennis was all dressed up because I had to give a talk to the Navy League in Los Angeles that night. I drove all the way down there — took about two-and-a-half hours — and gave a talk. We got home about 2:30 the next morning.

You earned your pay that day.

Chuck Yeager: Yup. All 30 dollars of it.

Weren’t you kind of beaten up, to go give a talk?

Chuck Yeager: Oh, your eyes are bloodshot from negative Gs, and you take a beating, but you either do or you don’t. That’s the way you look at it.

You’ve said that when you are in trouble, the last thing you do is talk. But I’ve always been struck by the kind of terseness of pilots like yourself, that ability to remain calm, or at least to sound calm.

Chuck Yeager: Well, yes. Obviously you don’t say anything. Some movies show the guy flying an airplane that’s on fire, trying to miss a school or… that’s a bunch of crud, boy. There is only one thought: self-survival. You don’t talk because that’s not part of your survival. And that’s the reason. There is a lot of misconceptions about emergencies in airplanes, but basically that’s the way it happens, and you either survive or you don’t. It’s just duty.

There is a fairly exciting chapter in your life that we haven’t covered, back in 1963, your Lockheed Starfighter experience. Can you describe, first, the plane’s capabilities?

Chuck Yeager: When I was commandant of the astronaut school, we had to train the guys in a simulated space environment. We took three F-104As, which was a mach two airplane, and we put a hydrogen peroxide rocket engine in the tail, above the normal jet engine [which] gave us an additional 6000 pounds of thrust. And with this aircraft, we also added 24 inches to the wingtip and two hydrogen peroxide thrusters, one out the top of each wing tip and one out the bottom. That’s for roll control above the atmosphere. We extended the nose of the airplane out and put thrusters in the top and bottom and each side for pitch control and yaw control of the airplane.

A typical mission that we flew with that airplane — and I flew it 40 some times, working out a profile for the students to fly as a test pilot on the airplane — we would take off with the afterburner on the engine, getting airborne. Clean the gear up on the airplane and the flaps, then accelerate out to climb speed, four to five hundred miles an hour, climb up to about 36,000 feet, then go into afterburner which accelerates the airplane out to about twice the speed of sound. Ease it up to about 45,000 feet, fire off the hydrogen peroxide rocket and accelerate it out to about 2.4 mach number. Then pull 4 Gs, or pull the airplane up into about a 70-degree climb angle. The characteristics of the J-79 engine, which is in the 104, as you go through about 55,000 feet, the afterburner blows out because of lack of oxygen. When this happens you gotta come out of afterburner position with the throttle in mil power and make the eyelids close to get more thrust out of the turbine engine. You gotta keep one eyeball on the tail pipe temperature, because that engine is going to over-temp at about 70,000 feet; it is not designed to run any higher. And when it does, you have to shut it down.

We shut it down and the hydrogen peroxide rocket takes you on over the top. We got the airplane up to roughly 118,000 max altitude. But then you are above 90 percent of the atmosphere, so you have to use these hydrogen peroxide rockets to change the altitude of the airplane to follow its flight path. When the airplane leaves, say, 100,000 feet going up like this, if you don’t do anything, it’s going to come back in that way. So you have to rotate it to make it come back in nose first.

We knew the 104 had a pitch-up problem, meaning when the airplane stalled, it pitched up. I was the first military pilot to fly the 104, on August 3, 1954. I was the test pilot on that airplane, so I knew it intimately. I spun the airplane a lot, and stalled it. I knew we had this problem.

What we were trying to establish was: When this airplane comes back into the atmosphere at a little higher angle of attack than we want, at what altitude will this aerodynamic force which causes the nose to pitch up on the airplane be more than the thrust of the hydrogen peroxide thruster in the nose which is pushing the nose down? We ran a series of flights; I was the pilot on it. Start at 118,000 feet, 116, 114, 112, coming into the atmosphere at about a 50-degree angle of attack, open up the thrusters at the top, push the nose down and then measure the rate. You can plot, at each altitude, at what rate the airplane recovers. We noticed it was starting to run into resistance at about 108,000 feet; 106,000 feet was a little slower. If you take the curve and extrapolate, it looks like we are going to run out of thrust in this hydrogen peroxide rocket where the aerodynamic pitch up will be more than the thruster, at about 92,000 feet. So we thought we were in pretty good shape.

We thought we would run one more. I flew a flight in the morning, with a pressure suit on, I think at 108,000 feet, and we measured the rotation. Then I landed and wanted to make another flight after lunch. I didn’t get out of my pressure suit because if you get out of it, it’s wet and you can’t get back in. I made another flight at about 1:30 in the afternoon, at 104,000 feet. For some reason, we had dual thrusters on the bottom of the nose and dual thrusters on the top. We don’t know, we may have had one thruster fail, but at 104,000 feet, when I came into the atmosphere at 50 degrees angle of attack, I couldn’t get the nose down on the airplane. You’ve already shut your engine down, and it gradually is slowing down. But the engine is still turning over, giving you hydraulic pressure, which runs the horizontal stabilizer for pitch control, the ailerons and the rudder.

What happened on previous flights, when you re-enter and force the nose down with the hydrogen peroxide thrusters, the altitude controllers, then you come back into the atmosphere nose first. Then you start getting air through the intake ducts of your airplane, that keeps your engine wind milling, you bring the airplane on down to about 40,000 feet, level out, hit the igniter and then come out of idle, out of stop cock with your throttle into idle. That gives you fuel and you start your engine up again. But if it doesn’t work, you go on down, dead stick into Rogers Dry Lake, which I did three or four times.

What happened on this flight was that when the airplane came into the atmosphere, at about a 50-degree angle of attack, I couldn’t get the nose down. The airplane pitched up and went into a flat spin. Now the airplane is in a flat spin, and because there is no air going through the intake ducts, the engine stops. When that stops, then you no longer have hydraulic pressure to run the horizontal stabilizer, the aileron or the rudder. So you are in a no-win situation. That’s exactly what it is. You sit there. But you have one other alternative, that’s eject. I also had a drag chute on the airplane that we use for landing. The airplane was in a very flat, slow spin. I had my pressure suit on and it was inflated. I sat there and watched. I was talking to Bud Anderson who was chasing me in a T-33. He was down, way down though, looking at me coming. I was talking to the space position branch, where the guys were recording data. I said, “I got a real problem. There is just no way of getting this thing out of a spin.”

So, as I went through 30,000 feet, I deployed the drag chute, which you normally deploy. When I did, the drag chute comes out and it popped the nose down on the airplane, but there is a link that the drag chute is hooked to the airplane with, that is designed to shear at 180 miles an hour. That’s in case the drag chute comes out accidentally while you’re flying, it won’t stop the airplane. It just so happened the nose went down as I went through 180 miles an hour, the drag chute sheared, the parachute released and the airplane pitched back flat because 180 miles an hour going through the intake duct is not going to give you engine rpm, it takes about three hundred miles an hour. So when this happened, it flipped back flat. I don’t think it turned, it just fell at one hundred miles an hour.

Now, you’ve got the egress systems, you know them intimately and it pays off, because a lot of times you have to use them in a semi-conscious state. I knew my rocket seat that I was riding in, I knew its capabilities. So, I rode it down to about 6,000 feet, which is not low, and ejected. The rocket seat blows you out of the airplane and gives you about one hundred mile an hour velocity away from the airplane. It just so happened that the airplane was falling at about 100 miles an hour, so when I used the seat, the airplane just fell away from the seat. The seat sat there, and then two seconds after you leave the airplane, the lap belt blows open on the seat, which is what holds you on the seat. You’ve got leg restrainers, cables that hold your heels into the seat for flailing when you come out at high speed.

I sat and watched the seat go through a sequencing, knowing when it was going to happen. Finally the lap belt popped open, and there is a butt kicker that kicks you out of the seat. I felt that go and also my cable cutters cut my leg restrainer cable from me [and] I fell through. When this happened, the F-5 release on your parachute is armed and as you fall through 1400 feet, the chute opens. Well, I was below 1400 feet, so the chute opened the minute that the F-5 release said to open, and it did. The problem was I didn’t have enough velocity through the air; I was just starting to fall again, to pull that quarter bag which is on the canopy of your parachute. The reason that bag is on the canopy is that when you eject at high speeds, four or five hundred miles an hour, it keeps your canopy on the parachute from popping immediately. The little pilot chute on that quarter bag needs about sixty miles an hour to pull it off the quarter bag. I didn’t know anything like this was going on. All I know is that I am free falling, my chute has released, but I haven’t got a canopy slowing me down because I can feel it flopping in the breeze. At about this time, the seat, which kicked me out up here, is also falling and it became entangled in the shroud lines of the parachute. I didn’t know this either, but this is the way it happened. Finally I picked up enough speed, 60 or 70 miles an hour, with the canopy up there following, that quarter bag came off, the canopy popped and when it popped, the damn seat that is entangled in the shroud lines flopped me up like this. The seat hit me in the face piece of my pressure suit. And what hit me was the butt end of the rocket on the seat, which still had glowing propellant burning. When this happened, it popped glowing propellant onto the rubber seals of my pressure suit. You are in 100 percent oxygen, and when it did, it ignited. And you’re feeding 100 percent oxygen and it’s like a blowtorch. Fortunately, when this happened, the visor on my pressure suit was busted and frayed, it cut my eye down and my eye socket filled with blood, so it didn’t hurt my eyeball. I got burned pretty bad on my neck and shoulder and it was very difficult to breathe. The only thing I knew, I was stunned from the blow. I knew I had to get the visor up on my pressure suit helmet. There is a button on the right, you push it and then you raise your visor. It’s the way you get your visor up on most pressure suits. I knew I had to get it off, get that visor up to shut the oxygen flow from my kit that was in the back of my pressure suit to get all this fire out. So I did that. Then I swung a couple times and hit the ground. I couldn’t see too much and I was having trouble breathing because there was a lot of smoke and fire. But as it worked out, I didn’t get killed in the flat.

I stood up and Andy buzzed me. Since I had been talking to them on the way down, four minutes from the first spin to impact, they had a helicopter off with a flight surgeon aboard, a doctor at Edwards. He got out there, probably within five minutes of the time I landed, picked me up, gave me a shot of morphine and took me back to the hospital. They worked on me, cut my pressure suit off and that was about it.

Normally, somebody else gets you out of the pressure suit, right? But you had to think fast.

Chuck Yeager: No, I just knew it. See, I wore pressure suits half my life.

It sounds like you had a tough time after that, dealing with your burns.

Chuck Yeager: Well, they can do a lot of scraping and ultrasonic work on your skin, a little skin grafting and stuff like that. That was part of the deal.

You look amazingly well, considering.

Chuck Yeager: Your body is a very forgiving thing.

Did you get the feeling that day that some big aviator in the sky was smiling down on you?

Chuck Yeager: Nope. You waste your time if you’re thinking about anything except surviving.

I bet at some point during that fall, you weren’t sure that you were going to survive.

Chuck Yeager: Well, you are too busy. You don’t think about anything like that. You are too busy trying to survive. Obviously, had I not known intimately my egress systems, meaning my pressure suit and ejection seat and parachute, I probably wouldn’t have survived. But I just make it a point to know it and it pays off a lot.

The extraordinary thing, hearing about this, is your ability to think under pressure instead of panicking.

Chuck Yeager: Well, you don’t talk anything about it. Obviously you can’t. You are too busy working the systems through. Knowing your egress systems is the answer. And also a little bit of luck was involved.

You also flew some amazing missions as a fighter pilot in World War II. Did that success come very quickly?

Chuck Yeager: Well yes. I learned quickly. We trained in the United States, before we went to England, in P-39s, old Bell Air Cobras. And it was all dog-fighting, air-to-ground gunnery, dive bombing, skip bombing, buzzing, really learning to fly a fighter. We were training to go overseas. Being the maintenance officer, I also had a lot of fun, just running test-offs on the airplanes when they came out of the maintenance. Yes, I was no better than the rest of the fighter pilots. I had very good eyes, as a lot of guys did, and also could dogfight, just a matter of experience. When we went to England in November of ’43, and we got the first P-51s in the Eighth Air Force, as I recall, we picked up a P-51 — I had never been in one before — and flew it from this assembly base down to our base in Leiston, and the next day, we are sitting over the middle of Germany fighting in them. You have to learn real quick, and that’s the way our pilots were. As I recall, on my seventh mission, I shot down a 109. It was my first airplane that I shot down. We were on a raid over Berlin, the first daylight-bombing raid over Berlin. I saw a 109, and I nailed him and, to me, it was a lot easier than I thought it would be, because we were a little bit apprehensive about dog-fighting the Germans in their fighters. They had a lot of experience dog fighting, and we didn’t. So I nailed the guy, but the next day I got shot down.

Let’s go back to March 5, 1944. Describe exactly what happened.

Chuck Yeager: I was in a dog-fight with three 190s, and I got hit head-on with a 20 mm cannon, and the prop came off the airplane, part of the wing, the canopy, and it caught on fire. So me and the airplane parted company. That’s the way it happens. You bail out, you free fall in your parachute, and then when you get down to within three or four thousand feet of the ground, you pull the ripcord, the parachute pops and you land. That’s about the way it happens. I picked up a few wounds. I had a couple slugs in one of my legs. I had some 20 mm fragments in my hands and a couple cuts on my head, but they were minor. So it didn’t make much difference. When I landed in my parachute, we were in occupied France, and there were quite a few Germans around. Obviously, you’ve got to hide or they will pick you up. And, I did. I dug into the woods as deep as I could, and hid. And they never caught me. I laid out there for a day, until things quieted down, and then contacted a French farmer or a woodcutter. I couldn’t speak French, but he could see I was an American flyer, because I had my flying gear on, leather jacket and flying suit. And he knew that I needed some kind of help. Fortunately, he went to the right people, instead of turning me in, got me with the resistance forces, the Maquis, who in turn took me under their wing for the next month. I worked my way down through France, finally went through the Pyrenees and into Spain, a neutral country.

Was it a little bit scary to trust this farmer? You couldn’t be sure what side he was on.

Chuck Yeager: No. You don’t have any choice. You either do or you don’t. That’s the way to look at it.

You had a 50/50 chance, I guess.

Chuck Yeager: Yes.

What happened when you got to Spain?

Chuck Yeager: Well, I was interned in the town of Lerida, and the American consul came up and talked to us, made sure we were American, then put us up in a hotel, gave us some money and we just bummed around there for about a month. Finally, in May 1944, we were beginning to help Spain who was running out of gasoline because they didn’t have any petroleum products, and we began trading gasoline for American pilots that were in Spain. There were something like 2600 airmen interned in Spain who either had made it through the Pyrenees or took their airplanes down and jumped out of them. And the way we got out was that the Spanish took us down to Gibraltar, and turned us over to the British on the island of Gibraltar. The British were flying airplanes from Gibraltar, over the tip of Spain and Portugal up to England, and I bummed a ride up on one of the airplanes, and then went back to my squadron.

According to military rules at that time, you were supposed to have been sent home after having any contact with French resistance.

Chuck Yeager: Well, basically, they didn’t want you to compromise the French underground system. And fortunately, I didn’t go straight back to my squadron when I got to Spain. I was held in sort of a secure house, where you couldn’t get out, until they interrogated you to make sure you were an American flyer. You know, they wanted your whole story. Where you got shot down, the outfit that you were with, and then they brought a pilot down from my squadron to identify me, and to make sure that I was who I said I was. Then they started publishing orders on me to go back to the United States. That’s when I sort of backed off and said, “I don’t want to go home, I want to go back to my squadron and fight.” And they said, “You can’t because the rules prohibit it.” Fortunately, the invasion was just coming along, and when the invasion occurred, the resistance forces surfaced, and General Eisenhower, whom I had worked my way all the way up to see, said, “Okay, go back.”

You really had a near miss there, being shot down. Why did you push so hard to fly again after that?

Chuck Yeager: Well, I knew if I came home as a flight officer, I’d stay a flight officer the rest of my life. That was my rank. I only had eight missions, so I had no reason to come home. The rest of the guys were still with the squadron flying.

The word fear didn’t enter your mind?

Chuck Yeager: Well no, that’s not part of my career.

How did you come to shoot down five German planes in one day?

Chuck Yeager: When we went over there in November of ’43 with the first Mustangs, we flew very long-range missions. The Mustang’s range, you could fly for eight hours and stay with a bomber all the way in and out. On this particular mission, I shot down three airplanes, and I was leading the whole fighter group, which means three squadrons. Our fighter group only had two boxes of bombers to escort. So I stuck the other two squadrons, one on each box of bombers, and took my squadron and ranged about 80 miles out in front of the bomber stream. I spotted 22 enemy 109s in a formation climbing up, out in front of the bombers, 80 to 100 miles. I stayed up-sun where they couldn’t see. I spotted them, they were just little specks. I had excellent eyes. I could watch things without them seeing me. I kept up-sun from them with my squadron of sixteen P-51s. Finally, when they leveled out and headed over towards the bombers, I just moved in behind them, down-sun. I got within two hundred yards behind them. They kind of spread out. We still had our drop tanks on because we wanted to keep as much fuel as we could. I shot down the first two without even dropping my tanks. Of course, with the explosions when the airplanes blew up, they all broke and at that point we punched our tanks off and the whole squadron broke up into elements, wingman and his leader to support each other. We got in a big old hairy dogfight, and I shot down another guy. I hammered him, and his wingman cut the power and dropped behind me. This one blew up and that broke into him. Pulled out at about 50 feet before I hit him. And then another guy, I followed him to the deck, got him down low and then it was all over with.

You left the fight following the guy down, then come back and look around. My wingman was still with me and I picked up a couple more guys flying out. You try to orient yourself, kind of fly around, pick up the bombers again and stay with them. That’s the way combat is. A lot of shooting, a lot of high Gs, a lot of turns and you gotta watch what you’re doing. It’s exciting.

Quite a day’s work there.

Chuck Yeager: Yes, and remember I only fired 151 rounds of 50-caliber ammunition. That’s 31 slugs per airplane. When you are working in real close, 100 feet, 200 feet, you are very effective.

How did you originally come to join the Army Air Corps?

Chuck Yeager: Probably the recruiter was better than the Navy or anyone else and also, I think, one of the guys who went through pilot training about the year that I graduated from high school. He came home. He was a pretty neat guy; he said it was a fun job. But flying, I never associated myself with it.

When I enlisted in the Army, it was just to be a mechanic. There was no intention to be a pilot, or anything like that. When I got in September of 1941, I was trained as a mechanic which was easy [because] I had already had so much experience in mechanical things, like engines and things that Dad exposed us to all the time that I trained and began working on airplanes as a crew chief. I serviced them, overhauled the engines, and things like that. Finally, I recall sometime around the latter part of November 1941, I remember reading a notice on the bulletin board that if you were a high school graduate, 18 years of age and could pass a physical, then you could apply for pilot training under the flying sergeants program. You wouldn’t be a cadet, or make lieutenant, or be an officer when you graduated from flight school, you’d be a sergeant pilot. And that looked like a pretty neat deal. I just did it just to be doing something. So I put in my application. I recall taking my physical on December 4, 1941, passing it and then just sweating it out for six months, and finally they called me up for pilot training. But that, you know, it’s just a matter of being in the right place at the right time.

It sounds like your first experience as a pilot was not all that much fun. Can you describe it?

Chuck Yeager: My first ride in an airplane wasn’t any fun. As I recall, it was the spring of ’42. I was a crew chief on an AT-11, which was a twin-engine bombardier-training airplane. I had overhauled one of the engines and the engineering officer had to take the airplane up and check it out, and he asked me if I wanted to go along. I had never been in an airplane before and I said, “Yeah, I’d like to.” So I got in and sat down in the seat and fastened the safety belt. He took off, and he went over to one of the dry lakes down there very near Edwards, between Edwards and Victorville, and started shooting touch and go landings, and it was rough and turbulent. Pretty soon I got sick, and threw up on the airplane. To me, it was a very uncomfortable situation. I didn’t particularly care for it, but I had already applied for pilot training. I think that’s the only time I went up in an airplane, and that was it, until they called me up for pilot training.

Did you get sick again?

Chuck Yeager: Oh, the first time or two going up. As long as someone else is flying, you get a little woozy. But then, when I started flying the airplane myself, all that went away.

Is that the difference between being a passenger and a pilot?

Chuck Yeager: Yeah, and getting used to it is primarily the thing. You can make anybody sick in an airplane, from motion.

How do you overcome that? Is it psychological?

Chuck Yeager: Basically it is, and physiologically becoming used to it.

We’d like to hear about your early years. What about your birthplace in West Virginia? What was that town like?

Chuck Yeager: I was born in Myra, West Virginia, which was actually just a post office on Mud River, very near Hamlin, West Virginia. My first recollection was when we moved to Hamlin when I was about four or five years old. And that’s where I spent my life until I was 18 years old. To me, it was a rural town, population of about six hundred. It’s in the middle of the hills. Primarily was agricultural, timber, coalmines, and some natural gas. My father was a natural gas driller.

I attended grade school and I did very well in the first grade, skipped second grade and went to the third grade. By the time I got to the fifth grade, I spent two years there. It got kind of tough. Grade school was just nine months out of the year. I enjoyed running the hills or fishing, and things like that.

In high school, things got a little more serious as far as my education was concerned. And also there were sports — football and basketball, which I played both. And I also played a trombone in the high school band and chased gals, so I was a pretty busy kid. The subjects that I liked very much in school were mathematics, algebra and typing. I could type 60 words a minute easy. Anything that took hand-eye coordination I had a good time at it. History, my teachers had trouble passing me.

Do you recall any books you read that had a big influence on you?

Chuck Yeager: That’s a long time ago. I was interested in books about wildlife, like some of Jack London’s books, as I recall. And then also another one, by an unknown author, called Crooked Bill, about a little bird that had a crooked bill. The reason I remember it is I had to give a book report on it. It was the hardest thing I had ever done in my life.

Really? Speaking in front of the class?

Chuck Yeager: Well, I was only in the fourth or fifth grade, and it was tough.

Were there any people that you were really influenced by as a kid, or impressed by?

Chuck Yeager: I, probably more so than the other kids, took up with elderly people, because they were interesting people. And there was one in particular who had been a state senator and he was a lawyer, old Jake D. Smith, and I hung around him a lot after I got to be a teenager because he was interesting to get a lot of tales from. He was a pretty nice guy. My dad was gone all week. Normally he would leave on Sunday afternoon, and he’d come home Friday night. He wasn’t around at that time, so I took up with older people, just for company.

What about this fellow impressed you?

Chuck Yeager: He was just an interesting guy. He was a very mature guy, so it was interesting to talk to him. Usually, the only other mature people you talked to were schoolteachers, and your relationship with them was entirely different.

Were there any teachers that you were particularly motivated by?

Chuck Yeager: No. I remember Mrs. Miller taught me typing, and I enjoyed her. And some of the math and algebra teachers I enjoyed. If you liked them, they taught you well. And if you didn’t like them, they were the people that couldn’t communicate with you, or teach you anything.

You mentioned that your dad was a gas driller. Maybe you could describe what that is.

Chuck Yeager: He had a string of cable tools. He’d drill holes in the ground for natural gas. He would go down some 3,000 feet into the ground. It was an interesting piece of machinery. I was exposed to machinery at a very young age. I liked it. I got to overhaul engines, and run big gasoline pumps and water pumps, and watch him dress bits, meaning heating them until they were red-hot and then re-sharpening the bits that cut the whole in the ground. It was interesting to me as a kid. I wasn’t as big as my big brother, who turned out to be about six-four and weighed about 240. He could handle a 16-pound sledgehammer and carry pipes. I couldn’t do that. I was just an average-sized kid.

Throughout your career you have shown an incredible drive to keep besting yourself and besting the world’s records. I wonder if that sense of ambition was there when you were a kid. Were you aware of it?

It was taught mainly through family discipline. My father taught me to finish anything I started. And I think that carries throughout your adult life. Most people’s personalities and moralities are formed when they are rather young, and that characteristic will carry out throughout their lifetime. We were disciplined as kids, quite severely, if you didn’t finish your jobs, and I think that’s what brought about a desire to finish what I start and do the best job you could. And that’s probably the reason that characteristic has carried throughout my life.

It’s one thing to finish a job, and have a sense of a job well done, but it’s another thing to do it better than anyone else. Was that part of your thinking?

Chuck Yeager: There is no kind of ultimate goal to do something twice as good as anyone else can. It’s just to do the job as best you can. If it turns out good, fine. If it doesn’t, that’s the way it goes.

But there is no such thing as a sort of half-assed attempt?

Chuck Yeager: No. Never has been.

We’ve heard your father was a stubborn fellow, a Republican among Democrats.

Chuck Yeager: He was a very honest guy. And his word was law. He was a Republican, and he believed in it, and he didn’t particularly care for Democrats although the Democrats in West Virginia were in the majority. But he was that way. He was sort of a Dutch-German guy, and he worked very hard, and he was serious about everything he did. He didn’t have to sign a piece of paper; his word was his bond.

I gather that many years later, he even refused to shake the hand of the President.

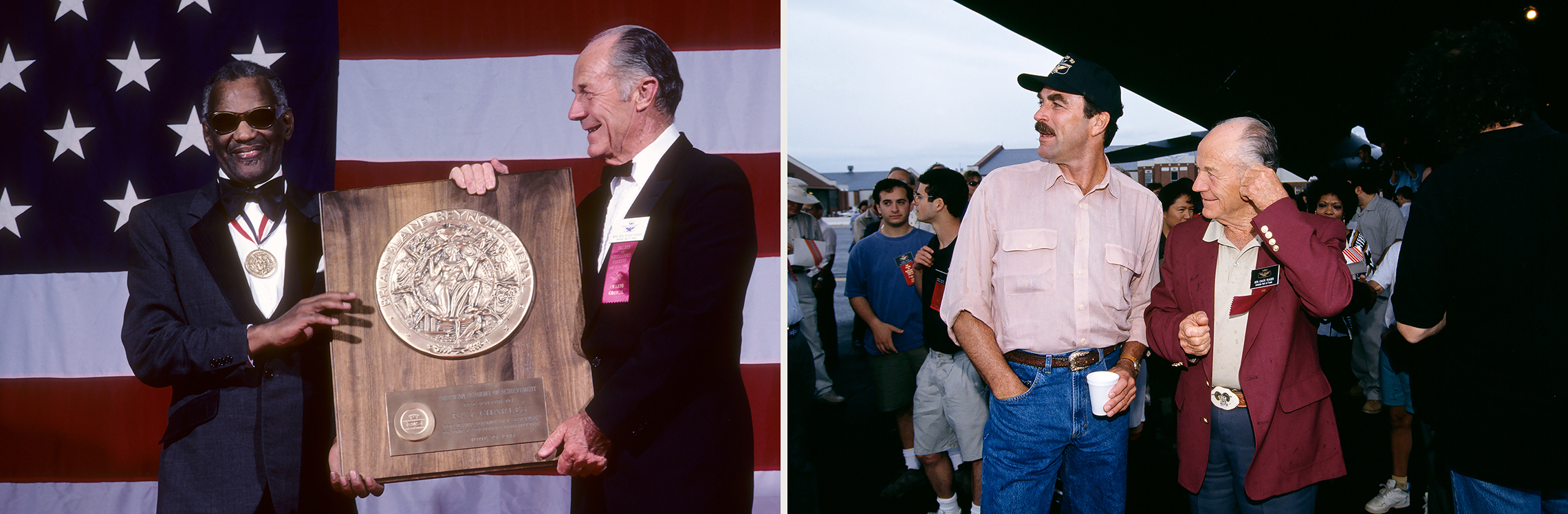

Chuck Yeager: That was many years later, around 1948. After I had broken the sound barrier, I went up to the White House to get the Collier Trophy from President Truman, and I remember my dad wouldn’t shake hands with him.

Do you suppose Truman was insulted?

Chuck Yeager: I don’t know. He probably didn’t pay any attention to it.

Were you a close-knit family growing up?

Chuck Yeager: Probably so. I have a big brother and a younger sister about three of four years younger than I am, and then a little brother ten years younger. We are a pretty close-knit family; we went to Sunday school and church and also played together and ran around together.

What sports interested you as a kid? I gather you were quite athletic.

Chuck Yeager: I played football and basketball in high school.

Did you intend to follow your dad into his profession?

Chuck Yeager: That’s speculation. The war broke out in Europe in ’39 and ’40. My senior year in high school was 1941, and we were mobilizing our forces here in America. It just seemed a natural thing for most all the kids in high school — especially the boys — to enter the service. I think we all did.

Did you have a vision of what you wanted to accomplish back then?

Chuck Yeager: No. Actually, when people tell you that, “I had my mind made up when I was two years old to do this,” I think you should take that with a grain of salt. Because it’s very difficult for a kid who is going through an educational process and being exposed to the world, to decide what he wants to do. Because he really hadn’t been exposed to that kind of a life yet. And I had no idea what I wanted to do, except exist and that was about it. I had no interest in airplanes; we didn’t even know what an airplane was. We didn’t even see them except flying in the air. So obviously, there was no interest in them at all.

Do you remember your first encounter with an airplane? How old were you?

Chuck Yeager: Fifteen or 16. As I recall, somebody said there was a Cub or something that had made an emergency landing in a cornfield, about a mile from the house. So I rode my bicycle up there to look at it. I wasn’t impressed, because I didn’t know what it was. So you just look at it, turn around and leave.

It wasn’t love at first sight.

Chuck Yeager: No. In fact, not knowing anything about airplanes, I didn’t have any intentions to be associated with them.

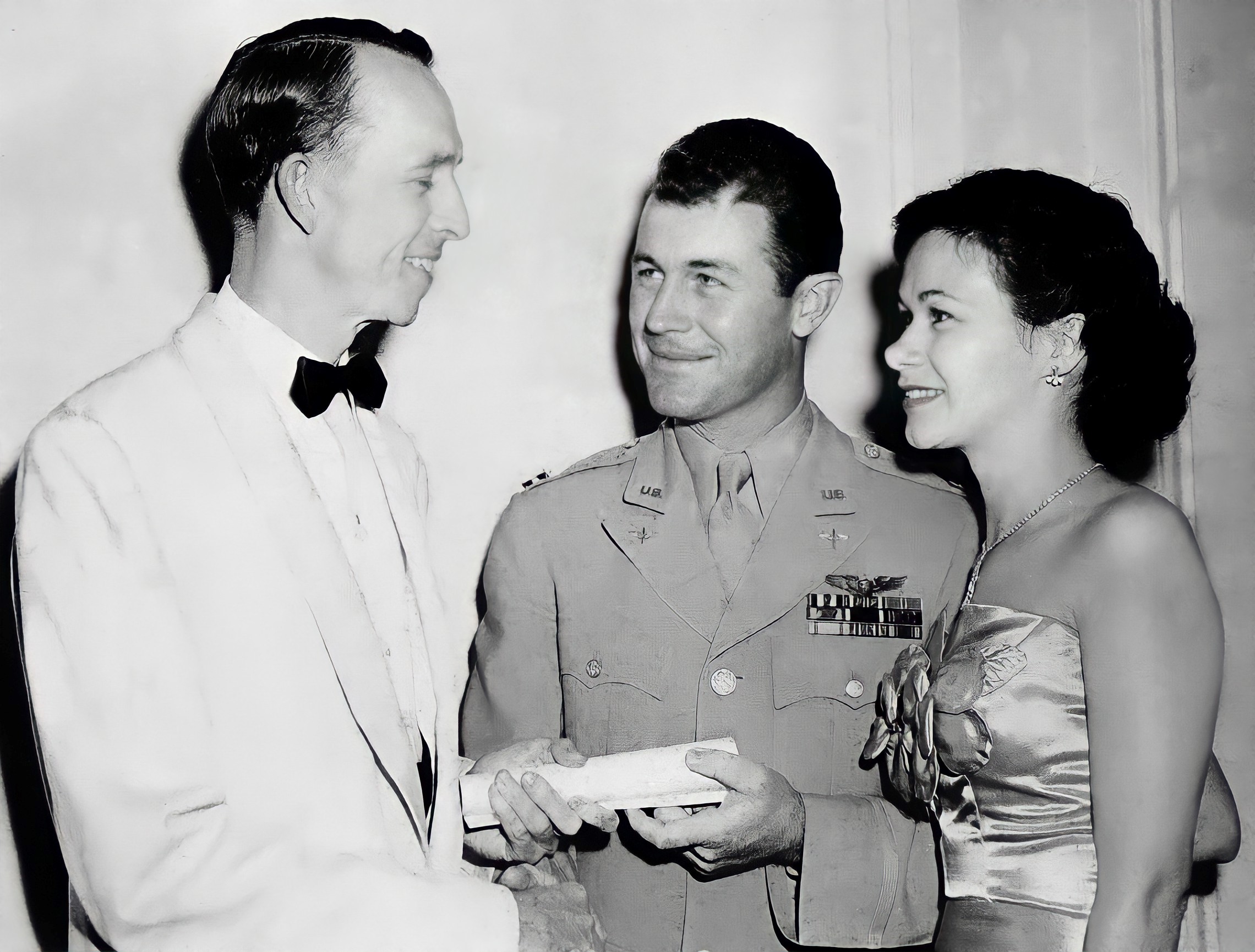

You got married right after the war, didn’t you?

Chuck Yeager: Well, I came home in February and got married February 26. I got home about the first of February, then went down to Texas to be a basic instructor and that’s when I got out of there into Wright Field in July of 1945 and got into maintenance.

I know that your wife was a very important support system for you, your whole life. And one of the things that amazes me in reading about your life is how brave she was to let you keep going up there.

Chuck Yeager: Well, I was flying when I met her. But the point is, being an Air Force wife is not an easy life. It was tough because you travel around a lot, and there is a high risk factor, obviously, especially in research flying. And she bowed her back and did it. And it worked out pretty good.

What was Colonel Albert G. Boyd’s influence on your early career?

Chuck Yeager: Well, that was after the war. When I came home, I didn’t go to Wright Field in 1945 to be a test pilot. I went overseas in November ’43, I fought in the war, got shot down, came home, and that one little thing — that I had gotten shot down in March 1944, evaded capture and went through the Pyrenees into Spain and was interned — when I returned to the United States, they made me a basic instructor in Texas. Then the war ended in Europe, and they freed all of the prisoners of war. Well, the Air Corps came out with a policy that those airmen, pilots, navigators, bombardiers and gunners who had gotten shot down could select any base in the United States that they wanted. Well that policy covered me, because I had been shot down and evaded, and was known as an “evadee.” Evadees and prisoners of war could select any base they wanted. So, I looked at the map, and Wright Field was the closest air base to my hometown in West Virginia, and I picked Wright Field.

When I reported to Wright Field in the summer of 1945, the personnel looked at my records and saw that I was a fighter pilot, but the one thing that caught their eye was that I was a maintenance officer, meaning that I had been trained as a crew chief in aviation maintenance, and then when I served in my fighter squadron in combat, I served as the maintenance officer. You know, running the crew chiefs and the maintenance guys. When I got back, they saw this, and there was a vacancy in a fighter test section there in the flight test division that needed a maintenance officer. And they assigned me there. I had hangars full of every kind of airplane that we were flying. It was interesting to me, because I got to fly every airplane. After they were worked on, then the maintenance officer had to take them up and check all the systems out, and sign them off, and then you turn them over to the test pilots to do their test work in them. And that’s how I got to Wright Field.

Now, over the next year, or six months, I put on many air shows in jets all over the United States. Colonel Boyd, who was chief of the flight test division, watched a few of those air shows and he was impressed. He noticed also that me being a maintenance officer, I never had any trouble with my airplanes. If something happened to them, I could fix them, and I always brought them home. So, that’s when he approached me in December 1945. He said, “Would you like to go to the test pilot school?” I said, “Well, I only have a high school education and it might be kind of tough for me, the academic requirements.” He said, “No, you can make out.” And so I went into the test pilot school, and that’s what got me started in the test program. And then later, when the X-1 came along, in 1947, he selected me for the test program. And the reason he did was that I understood machinery, and obviously could fly an airplane.

What do you think he saw in you, in your personality?

Chuck Yeager: I don’t know. Personality to him didn’t mean a heck of a lot. It’s just your ability to perform in an airplane. And that caught his eye. Also he knew that the X-1 was a very dangerous program, and that I could take care of myself.

We’d like to hear about the beginnings of the space program, and your involvement with that. Were you disappointed not to be chosen as one of the Mercury Seven?

Chuck Yeager: Naw. Number one, when the space program started in 1959, I left Edwards in ’54, after nine years there as a test pilot, and went to Europe to become a squadron commander in an F-86 squadron, and get back into running a fighter outfit.

When I came home to George Air Force Base, I had an F-100 squadron and I was back in tactical flying. Test work is a very demanding type of flying. You fly a dozen different airplanes every week and you really don’t feel comfortable in them, but you know the systems. But also, it’s a lot of competition in test work. When you get into tactical flying, back in the fighter squadron, you fly only one airplane, stay combat ready and know your guys. It’s a pretty nice way of life. So I came back and I was at George when the space program started in ’59. The requirement to get into the space program was to have a degree, preferably engineering, math or one of the sciences. I only had a high school education. I didn’t give it a thought. I couldn’t care less about it because to me it wasn’t flying, it was riding in capsules.

I didn’t pay a lot of attention to the whole space program until 1960 when I went through the War College and was promoted to full colonel. And when I had gotten out of the War College, they assigned me back to Edwards Air Force Base and put me in charge of the test pilot school. When I moved into the test pilot school, there were a couple of programs coming within the Air Force: the X-20 Dyna-Soar Program and the MOL Program, Manned Orbital Laboratory. Both of those were space weapons systems. The Air Force was very much involved in space. In fact, it was responsible for space. The NACA, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, was basically aeronautics.

When I took over the school, we started a space course in the test pilot school, changed the name of the school to the Aerospace Research Pilots School and we started training guys for potential astronaut duties. Those astronauts were selected for the Manned Orbital Laboratory and the X-20 Dyna-Soar. The X-20 Dyna-Soar was very similar to the space shuttle, except it was only probably one-third as large. It was strapped on a Titan 3C liquid rocket with two strap-on solid boosters, just like the shuttle, and it would go into orbit, then re-enter and land the same way the shuttle does. Instead of wheels, it had skids to land on, like the X-2 had. We bought a whole space mission simulator for something like six million bucks, and we had it set up in the school. We could have simulations on a whole space mission, including rendezvous and docking in space. We had the astronauts training in the MOL program, and the X-20 program was going along.

And finally, in late ’65 or ’66, the administration made a decision that space would be for peaceful purposes. They canceled the X-20 and the Manned Orbital Laboratory, and formed NASA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. And when this happened, the Soviet military moved right into the void in developing space weapons systems. We’d already been through the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs. We did away with our whole space mission simulator and went right back to test pilot training at the school. I left and went to Vietnam. I was really, really disappointed with what our government, the White House or the administration, had done, because we had a tremendous capability in the Air Force for space. We would have been 15 years ahead of where we are today with NASA running the space program. And that’s the story of my six years at Edwards in astronaut training.

It was amusing. We ran a class through of roughly 11 pilots per year; 38 of the guys that graduated from the school while I was commandant went to NASA as astronauts: Dick Truly, who is now a colonel, was one of my students; Bob Crippen, Frank Borman, Tom Stafford, the whole bunch. They’re a good bunch of guys and we had an excellent facility there, but it was wiped out.

Aside from your opinion that we’d be 15 years ahead of where we are now, do you still think that it was a poor decision?

Chuck Yeager: Definitely, a very poor decision. Because we have gone ahead and developed space weapons. We had to because of the Cold War with the Soviet Union. The situation developed a need for space weapon systems, the Strategic Defense Initiative — SDI or “Star Wars” defensive concept. Incidentally, a lot of that technology that was developed to support the SDI program — or Star Wars — is the reason that the Patriot missile is so successful today against Scud missiles. That’s technology that’s associated with space weapons.

Back in the early days of the Mercury program, I gather that the idea of shooting off in a space capsule was not an attractive proposition to you.

Chuck Yeager: Like I said, it wasn’t flying, it was just riding in something that you had no control over. Number one, I wasn’t eligible. Number two, I could care less. It’s interesting. I’m sure that the view was pretty, but that’s about the only thing you could say for it.

You’ve expressed concern over several decades that astronauts, as they have been called, were not given as much of a leadership role as perhaps they should have.

Chuck Yeager: I think one of the big problems that the astronauts are faced with is that they were not exposed to their hardware enough. They were being used, running around the country on PR jobs instead of getting involved in the design and manufacture of the hardware that they were going to be riding in and having more to say about some of the characteristics of it. I think that was obvious during the shuttle accident. The guys really didn’t know a damn thing about what the hell was going on around them. They’d leave it up to some bunch of engineers, both civilians and NASA, and that’s what bit them. They should have been involved more with it.

Do you think NASA is moving more in that direction now?

Chuck Yeager: Yes. After the accident and the long period of time, there were a lot of recommendations from the accident board, which I was a member of, that the astronauts get more involved in the hardware so that they understood the systems and had more of a say about whether they flew it or not. Yes, that’s taken care of. There have been a lot of changes in NASA. A lot of changes still need to be made, but there have been a lot made.

This would imply that you need different characteristics to become an astronaut. More technical.

Chuck Yeager: No, that’s not true. The guys who are selected for astronauts have good technical background, they have capabilities to absorb technology, and they do. But they are crowded a little bit with PR work.

What other problems do you see with NASA as it stands?

Chuck Yeager: Basically, the bureaucracy. It’s a civil service organization. It’s difficult to get dead wood out of it, it has a tendency not to let loose of operational programs and keep on doing research and development. The shuttle is a good example. We could probably run the shuttle program for about one-tenth of what it is costing today with a good civilian organization that’s in it to make a profit.

You’ve been outspoken about these things for many years, and I imagine that alienates some of the administrators at NASA.

Chuck Yeager: I don’t lose any sleep over it.

You had a little encounter with Neil Armstrong, back in test pilot days. Could you tell us about that?

Chuck Yeager: The X-15 which Neil was flying, about six other pilots were flying at the same time like Pete Knight, Bob White, Bob Rushworth and Joe Engle, it flies just like the old X-1. The X-15 is launched from a mother aircraft, within gliding distance of a dry lakebed. Since the X-15 was getting up to speeds of four and five times the speed of sound, you obviously couldn’t launch it over Rogers Dry Lake. It had to be backed up and launched over a dry lakebed, like Mud Lake in Nevada or Smith’s Ranch Lake, up east of Fallon, Nevada, or some of the Panament Lakes in Nevada, and then make its run and recover at Rogers Dry Lake. If the dry lakes are wet, you can’t land safely an airplane that comes in at a couple hundred miles an hour. You can tear off the gear or skid, and end up tumbling.

I was running the Aerospace Research Pilots School at that time, some time around ’65, when NASA — or Paul Bickel, who was the administrator of NASA there at Edwards — called me and said, “What do you think about Smith’s Ranch Lake?” I said I was just up there yesterday in a B-57 looking at it, and it’s wet. He said, “My guys say it isn’t wet.” So I said, “Be my guest.” That’s exactly what I said. He said, “Would you go up there and land on it?” I said, “No, I won’t. It’s wet.” And he said, “Would you ride with Neil in one of our airplanes?” I said, “Yeah, as long as I’m not responsible for anything that happens.”

So I went over to NASA, and they had a T-33 and Neil was flying it. I took my chute and helmet over, and we just wore light flying suits and gloves. I got in the back seat and sat there. Neil taxied out and took off on the dry lake bed, we fly up to Smith’s Ranch Lake, he backs off, comes in and he’s going to touch down. I said, “Neil, the lake is wet.” He said, “No I think it looks dry enough for me to just touch down, let it roll, and I’ll add power and come back off.” I said, “You get on that lake surface in a T-33, and it starts sinking in, you’re never going to overcome the drag with the power, if you are at about 5000 feet elevation where the lake bed is.” And that’s exactly what happened. He came in, touched down, the airplane starts slowing down, he puts full power on it, it keeps slowing down and, finally, it just stops and sinks in the mud. We are sitting there, shut it off, now what? We are thirty miles from a road, it’s about 3:30 in the afternoon, it’s cold and you’ve got 30 miles to walk with a thin flying suit on. Fortunately, Paul Bickel sent a Gooney Bird, a C-47 that NASA had down there, to follow us because he suspected something might happen. Good insurance. We sat there for about half an hour, sitting on the wing of the airplane. You could walk on the lakebed and it would leave footprints, but pretty soon the old Gooney Bird homed into sight. I got back in the airplane, put the battery switch on and turned the radio on. I said, “We only got one choice. If you land over next to the edge of the lake and keep the airplane rolling, you probably won’t sink, and then we can get back off the ground. Give us time to walk over to the edge of the lake. Don’t slow the airplane down. Keep the door open and we’ll jump aboard.” And he did. He landed and slowed it down. He was leaving a pretty good rut in the lake, but he kept the power on and as he came by we ran along and jumped in the back end of the airplane. When we got back to Edwards, it was after dark. The T-33 sat up there; the Navy went out and recovered it a week later. It was just an experience. You know things because you live on those lakebeds, like I had since 1945. And the guys, they don’t use their head. That’s a good example.

It’s not the most flattering picture of the man that walked on the moon.

Chuck Yeager: Well, Neil was a pretty good engineer. He wasn’t too good an airplane driver.

What do you think of the direction NASA is going in today? What do you think the big priority should be?

Chuck Yeager: I think that basically we are stuck with the shuttle. It’s that simple, because of narrow-mindedness and not looking at what’s available in the world. NASA doesn’t have any choice; it’s pretty well hamstrung as to what its goals are in the future and what they can accomplish. Since it’s the only kid we’ve got, we’ve got to support it. If we look at the laboratories that we are building, space vehicles out in permanent orbit and also the moon as a possible launching site for deep space exploration — manned and unmanned — they should be supported about the same amount as far as I’m concerned. The year that I spent on the President’s space commission, developing a master plan for what the United States should do in space for the next fifty years, was very interesting in that you went through all of these things. That was the year prior to the shuttle accident, and we went to our industry to get answers. What do you think we can do in space? We went to the academic world and NASA, who is supposed to be our experts in space. The one thing that we noticed when we started going to the different NASA centers, like JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratory), Marshall and others, is that these people don’t even talk to each other! They don’t even know what each division is doing. The different levels of supervision at NASA don’t even communicate. For a whole year we sat and looked at this, and then bang, the shuttle accident happens, because of those characteristics. It was unfortunate.

Today, NASA has cleaned up its act quite a bit. They are being a little overcautious, which is costing them in payload with the shuttle. Also, they are over-budgeted. They don’t get more money than they need; they are just spending a heck of a lot more than they need to. It’s unfortunate, but that’s the only space program that we have. Except the Air Force has been quietly developing space weapons systems the last 15 years, just for its own defense. That has paid off now in things like the Patriot missiles.

If you had been in charge that morning, would you have taken the fire call concerns more seriously?

Chuck Yeager: Definitely. You see, that’s the problem. There were no lines of communication between the different levels of supervision in NASA, so these guys don’t know that there is a problem. I think there are a lot of things that entered into the shuttle accident, and one was the PR pressure of getting that launch off on schedule. The press is there. And that, plus a lack of communication and not paying attention to red flags. A lot of this is Monday morning quarterbacking, but it did happen and it shouldn’t have happened.

I have some sense that the shuttle was sort of flown by committee.

Chuck Yeager: It was built by Rockwell to specifications and simulators, and the guys flew it. A lot of people raised their eyebrows when the Soviets flew a similar space vehicle from launch to touch down, without a crew aboard. The shuttle can do that. It just so happens the guys take over on base leg, and touch down on Rogers Dry Lake. They don’t have to.

In 1968 you were promoted to the rank of brigadier general. You once referred to that as your “miracle star,” didn’t you? Why?

Chuck Yeager: I don’t know. That’s probably a misconception. A miracle star. I figured I was pretty lucky to make general. I only had a high school education. I came in as a GI — an enlisted man — and worked up. I ran a pretty good outfit. And always had good wings and the guys liked me.

That’s putting it mildly. Talk if you will about some of the other historic aircraft you flew. The X-5, for instance.

Chuck Yeager: Well, the X-5 was the first variable swept wing airplane that we built. It was just one of the family of “X” airplanes, meaning research. Like the X-1 was supersonic, X-2 was hydrosonic, the X-3 was supersonic intake ducts, the X-4 was a semi-tailless airplane and the X-5 was a variable swept wing airplane. It was designed to sweep its wings from 20 degrees back to 60 to see what mach drag did on variable swept wings. We built two of them. A guy named Ray Popson got killed in one, in a spin, and we finished the other one up and it’s back in the Air Force Museum in Wright Field now, just like a lot of them. We built two X-4s and I flew all of them. One is at the Air Force Academy and one is in the museum. The X-3, there is one still, I think, back in the Air Force Museum. The X-2, we lost them.

They can’t all be gems, I guess. How did you feel about the F-104 after that?

Chuck Yeager: Oh, I flew it a lot, sure. I flew it a lot after that.

So in general you feel it’s a good plane?

Chuck Yeager: Yeah. You see, we used it in the school for space training. It gave you a minute and a half of zero G, gravity-free flight, above 75,000 feet with a pressure suit and a hydrogen peroxide control, same as a space capsule, and you can do it pretty cheaply. But then in 1966, the Air Force was out of the space business, so we canceled everything.

Looking back on all those planes that you flew over the years, and that you still fly, did you have any favorites?

Chuck Yeager: You don’t. You like the P-51 because you flew it in combat. It was a good airplane. But today, the newer the airplane, the better it is. It’s just like a car. You get a 1991 Cadillac, you got high tech, a lot of computer technology in it, versus a 1980 Cadillac. It’s just better and more fun to drive.

There are a lot more complex controls and use of the computer in planes today.

Chuck Yeager: We ran into a problem back in ’50s, when we were able to fly airplanes at supersonic speeds. All the fighter aircraft that we have designed, even from World War I to World War II, has to be very maneuverable. It also has to have a little bit of stability so that the pilot can handle it. The fighters that we designed in World War I and World War II, and even in Korea, those fighters had a limited stability capability and were made very maneuverable. Now, when we were able to smoke these airplanes out beyond the speed of sound and get a supersonic flow over the whole airplane, they became very stable. We found ourselves in a position in the ’50s and early ’60s, that when these airplanes were flying at supersonic speeds, although they were very maneuverable under the speed of sound, when you got them above the speed of sound, they were too stable to maneuver.

So we had to back off and make fighters very unstable down at slow speeds so that they would be maneuverable above the speed of sound. And what this meant was that when we designed airplanes like the 104, 105 and the F-4 Phantom 2, they were so unstable at low speeds, you had to put stability augmentation systems in like pitch dampeners, yaw dampeners, and roll dampeners that sort of stabilized these airplanes so the pilots wouldn’t have too much trouble flying them. Consequently, that’s where we found ourselves in the ’60s time period with airplanes, and it was a problem.

These airplanes, like an F-4 Phantom 2, when you turn the airplane, if you exceed the maximum angle of attack, it will spin out. And if it gets into a spin, it’s so unstable, you can’t get it out of the spin. So in the spring of 1970, a new technology came along, computer technology, and that made it possible for the Air Force then to design a flight control system that the computer used. We could then program the computer that was flying the airplane to never let that airplane exceed the maximum angle of attack, or yaw angle, regardless of what the pilot called for. Because when you are dog fighting, you don’t pay a lot of attention, you are in a high G-load, attacking things like that. Well, this really paid off. Then the F-16 came along some 18 years ago, in the ’70s, with a computer flight control system in it that was programmed never to exceed the maximum angle of attack, and that gave us a very maneuverable airplane at supersonic speeds, and it was a fall-out from this computer.

What was happening also, all of our fighters, like F-4 Phantom 2s, were carrying 28 different kinds of weapons. To manage each of those weapons requires a checklist. It looks like Sears and Roebuck’s catalogue. And what happened, because of the computer capacity in these computer flight control systems, we could then program all of the data necessary to manage all these weapons that you could carry, and that brought about a requirement for the cathode ray tube in the cockpit, just like a table-top computer. The first F-16s didn’t have them. The F-18, which used digital computer flight control systems, had cathode ray tubes so that we could program all the data into that computer to manage these weapon systems, and the cathode ray tube was put in there so that the computer could communicate with the pilot and give him the data necessary to manage the weapons. That’s where we are today, everything is computer enhanced.

We have gone to infrared, like the films you see with the laser spot guided bombs, or optically guided bombs. That’s all infrared that you are looking at; the pilot can work at night as well as he can in the daytime. And that’s the way things are progressing. A lot of new technology is coming about now, especially stealth. Stealth is the secret to survival today because every country in the world has radar in air defense systems, and if we can neutralize that 50 years of research in radar with stealth technology, that neutralizes all the air defenses that you are exposed to. Like the F-117, which was built some ten years ago, is not a good flying airplane, it’s not even supersonic, but it does have stealth technology. It can go in and drop laser-guided bombs very accurately.

Today, with airplanes like the new advanced technical fighter family, the F-22 and Y-23, these are a new advanced family of stealth fighters which fly at mach two, and they supercruise, which means you don’t use afterburner in them. They supercruise out at very fast speed and they have stealth technology so you can evade any radar. So that’s what’s happening today.

Is it difficult for a pilot today to be aware of the computer, and fly the plane at the same time?

Chuck Yeager: No, it’s your job. It’s just like driving a car and talking over a cellular phone while you are driving. It’s real easy because you are raised with it. In fact, computer technology is something that makes you a lot more effective in your airplane. A pilot today flying something like an F-18 or an F-20, F-22 or 23, is probably ten times more effective in that fighter than he was just three or four years ago. The new technology that’s going into smart bombs and missiles is really making a fighter very effective. The one thing you have to also realize, is that the defensive missiles, air-to-air missiles that some guy is shooting at you, is also going up that technology line, and they are becoming very lethal.

How would you account for the rather swift assertion of air superiority the U.S. took over Iraq (in 1991)?

Chuck Yeager: Basically technology: the laser-guided bombs, optically guided bombs, the initial stealth capability with the 117s going in and neutralizing a lot of the command and control network and radar network. It puts them in a very bad place. Also, AWACS, the airborne warning radar. Airplanes are sitting up there looking at everything that’s going on over the whole country of Iraq, on the ground as well as in the air and are also tied into the communications systems of Iraq. That’s the reason the guys that are going in know exactly what they are faced with. Also, the AWACS airplane uses electronic counter measure systems against radar, and other weapons detection systems. The airplanes are carrying electronic counter measure pods on them and they are very effective.

A pretty different scene than back in World War II.

Chuck Yeager: Yeah, but that’s evolution. Like Teflon skillets and microwave ovens. That’s the way it goes.

Do you think the same skills are nevertheless necessary for a great pilot today?

Chuck Yeager: Yes, sure. He’s very much in the loop. In fact, he is very good at what he does, and he has to be in the loop. The airplane won’t do it without him. And all this computer enhancement just makes him better at what he does.

But you still have got to have the same guts too.

Chuck Yeager: There are a lot of duty-oriented pilots out there today. In fact, they all are. They are very dedicated, as we were in World War II, Vietnam or Korea. And it shows up today too.

What about the remote control aspect of airplanes?

Chuck Yeager: Remote control, you will see maybe in the future, six or eight years down the road. Ten percent of your fighter force will probably be remote control stuff. You control from AWACS airplanes, small, miniature fighters with no crew, launched from C-130s or ground launched with air-to-air missiles and sensors. You can sit there and look out of a video camera out of the nose, in your AWACS airplane, in a nice soft chair, drinking coffee and shoot the guys down. It’s pretty neat, a pretty neat setup.

Do you think technology has removed a lot of the stress of being a pilot?

Chuck Yeager: No. You are still exposed to high G loads, and also you are in a hostile environment. Anytime you’re smoking along at mach two in an airplane, depending on a piece of mechanical equipment to keep you alive, the stress is still there, especially the high G loads. Airplanes we flew, like in World War II or Vietnam, were stressed for 7.33 Gs. The airplanes today — F-16, 18, 20, 22, 23 — are stressed for nine Gs.

What are you flying these days?

Chuck Yeager: I stay current in F-15, F-16s. I’ve been working on the F-23 for about four-and-one-half years, from its inception. I still fly F-4s and T-38s. Since I retired in ’75 I’ve had a job at Edwards as a consultant test pilot, a civil service job. The only reason I got it was so they wouldn’t lose my expertise or long experience. It’s interesting, because if you lay off a year, you will never catch up. Things are happening very fast. I’ve been lucky. I still have the same eyes I had as a kid, and stay in pretty good shape.

That’s true, a lot of pilots have retired at your age. In your career, what do you think was the role of being in the right place at the right time?

Chuck Yeager: That has a lot to do with it, beginning in the right place at the right time. Being able to take advantage of the situation, because of experience. A lot of luck is involved.

You’ve said that it wouldn’t have done you a lot of good to be born the year the Concorde first flew.

Chuck Yeager: I had the fun of flying prop airplanes, the early jets, rockets and watching the space program. And also being able today to participate in a lot of the research that is going on at Edwards Air Force Base. It’s interesting. I flew the F-15E, which is the premier airplane, air to ground with auto terrain following and infrared laser capability. It was an interesting program and the airplane is doing a very good job.

Looking back at your career, there were several points where many people would have retired and sort of rested on their laurels — 1947, ’53 — but I don’t think you ever considered that.

Chuck Yeager: No. It would be boring sitting around drinking beer, watching TV. It’s a lot more fun to be interested in something and be involved in it. I don’t spend all my life in airplanes. I have a lot of fun hunting and fishing, working on my car, doing woodwork or things like that.

What advice would you have for a young person who wants to be a pilot today?

Chuck Yeager: Don’t be too narrow in your goals. That’s the one thing. You say, “I’m going to be an astronaut when I grow up.” He sits there and doesn’t see all kinds of good opportunities go by him, that he could latch on to.

Do something that you like. Forget about the pay for Christ’s sakes. Regulate your style of living, your lifestyle, to fit your income. Just have fun in your job, that’s the main thing. Too many people think, “Well I’ve gotta make so much money, I’ve gotta get this kind of a paying job.” And it’s a strain to make ends meet. Everybody that I’ve ever seen that enjoyed their job were very good at it. That included flying airplanes too.

You’ve talked about the word “duty” a lot. But it seems that fun also played a big role in your work.

Chuck Yeager: To enjoy your job, fun enters into it. There are a lot of long hauls, and hard knocks, but in the end, you look back, it was fun.

There is a well-known quote from Thomas Edison about genius being “one percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration.” You obviously had a great talent in your field, but you really worked at it as well, didn’t you?

Chuck Yeager: Yes. Because in the end, experience is what counts. The more experience you have, the better you are. And that’s true of anything you do in airplanes, dogfighting in combat, or anything like that. Your chances of coming out on top depend on your experience level. The more experience you can get, the better chance you have of surviving in a war, or in any situation where you are faced with an emergency.

You’ve talked about advice for a young pilot, what about for a young person going into any field? What are the qualities you think are necessary for success?

Chuck Yeager: Knowledge of your job. That’s obvious. And also to enjoy it. There is not an easy answer to every question. I mentioned a while ago, there are too many kids that are too narrow in their scope when they start looking at their goals, and they let a lot of marvelous opportunities pass them by. That’s the thing that happens a lot.

We’ve read that you weren’t completely thrilled with the depiction of your exploits in the film version of The Right Stuff.

Chuck Yeager: No, the point was, The Right Stuff was not a documentary. It was entertainment. The Air Force came out smelling like a rose, but a lot of the things that were depicted in that movie were pretty fictional, you might say.

Like what?

Chuck Yeager: The physicals the guys went through and some of the special effects. Going mach one, the blue sky turning red. You don’t even look out the window.

That suddenly brought you even more fame, and the attention of a younger generation.