When God calls you to a great task, He provides you with the strength to accomplish what He has called you to do. Faith and prayer, family and friends were always available when I needed them…I learned that when you are willing to make sacrifices for a great cause, you will never be alone.

Coretta Scott was born in Heiberger, Alabama and raised on the farm of her parents, Bernice and Obadiah Scott, in Perry County, Alabama. She was exposed at an early age to the injustices of life in a segregated society. She walked five miles a day to attend the one-room Crossroad School in Marion, Alabama, while the white students rode buses to an all-white school closer by. Young Coretta excelled at her studies, particularly music, and was valedictorian of her graduating class at Lincoln High School. She graduated in 1945 and received a scholarship to Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio.

As an undergraduate, Coretta Scott took an active interest in the nascent Civil Rights Movement; she joined the Antioch chapter of the NAACP, and the college’s Race Relations and Civil Liberties Committees. She graduated from Antioch with a B.A. in music and education and won a scholarship to study concert singing at New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts.

In Boston she met a young theology student, Martin Luther King, Jr., and her life was changed forever. They were married on June 18, 1953, in a ceremony conducted by the groom’s father, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Sr. Coretta Scott King completed her degree in voice and violin at the New England Conservatory, and the young couple moved in September 1954 to Montgomery, Alabama, where Martin Luther King, Jr. had accepted an appointment as pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.

They were soon caught up in the dramatic events that triggered the modern Civil Rights Movement. When Rosa Parks refused to yield her seat on a Montgomery city bus to a white passenger, she was arrested for violating the city’s ordinances giving white passengers preferential treatment in public conveyances. The black citizens of Montgomery organized immediately in defense of Mrs. Parks, and under Martin Luther King’s leadership organized a boycott of the city’s buses. The Montgomery bus boycott drew the attention of the world to the continued injustice of segregation in the United States, and led to court decisions striking down all local ordinances separating the races in public transit.

Dr. King’s eloquent advocacy of nonviolent civil disobedience soon made him the most recognizable face of the Civil Rights Movement, and he was called on to lead marches in city after city, with Mrs. King at his side, inspiring the citizens, black and white, to defy the segregation laws. The visibility of Dr. King’s leadership attracted fierce opposition from the supporters of institutionalized racism. In 1956, white supremacists bombed the King family home in Montgomery. Mrs. King and the couple’s first child narrowly escaped injury.

The Kings had four children in all: Yolanda Denise; Martin Luther, III; Dexter Scott; and Bernice Albertine. Although the demands of raising a family had caused Mrs. King to retire from singing, she found another way to put her musical background to the service of the cause. She conceived and performed a series of critically acclaimed Freedom Concerts, combining poetry, narration and music to tell the story of the Civil Rights Movement. Over the next few years, Mrs. King staged Freedom Concerts in some of America’s most distinguished concert venues, as fundraisers for the organization her husband had founded, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Dr. King’s fame spread beyond the United States, and he was increasingly seen not only as a leader of the American Civil Rights Movement, but as the symbol of an international struggle for human liberation from racism, colonialism and all forms of oppression and discrimination. In 1957, Dr. King and Mrs. King journeyed to Africa to celebrate the independence of Ghana.

In 1959, they made a pilgrimage to India to honor the memory of Mahatma Gandhi, whose philosophy of nonviolence had inspired them. Dr. King’s leadership of the movement for human rights was recognized on the international stage when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace. In 1964, Mrs. King accompanied her husband when he traveled to Oslo, Norway to accept the Prize.

In the 1960s, Dr. King broadened his message and his activism to embrace causes of international peace and economic justice. Mrs. King found herself in increasing demand as a public speaker. She became the first woman to deliver the Class Day address at Harvard, and the first woman to preach at a statutory service at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. She served as a Women’s Strike for Peace delegate to the 17-nation Disarmament Conference in Geneva, Switzerland in 1962. Mrs. King became a liaison to international peace and justice organizations even before Dr. King took a public stand in 1967 against U.S. intervention in the Vietnam War.

On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. Channeling her grief, Mrs. King concentrated her energies on fulfilling her husband’s work by building The Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change as a living memorial to her husband’s life and dream. Years of planning, fundraising and lobbying lay ahead, but Mrs. King would not be deterred, nor did she neglect direct involvement in the causes her husband had championed. In 1969, Coretta Scott King published the first volume of her autobiography, My Life with Martin Luther King, Jr. In the 1970s, Mrs. King maintained her husband’s commitment to the cause of economic justice. In 1974, she formed the Full Employment Action Council, a broad coalition of over 100 religious, labor, business, civil and women’s rights organizations dedicated to a national policy of full employment and equal economic opportunity; Mrs. King served as Co-Chair of the Council.

In 1981, The King Center, the first institution built in memory of an African American leader, opened to the public. The Center is housed in the Freedom Hall complex encircling Dr. King’s tomb in Atlanta, Georgia. It is part of a 23-acre national historic site that also includes Dr. King’s birthplace and the Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he and his father both preached. The King Center Library and Archives houses the largest collection of documents from the Civil Rights era. The Center receives over one million visitors a year, and has trained tens of thousands of students, teachers, community leaders and administrators in Dr. King’s philosophy and strategy of nonviolence through seminars, workshops and training programs.

Mrs. King continued to serve the cause of justice and human rights; her travels took her throughout the world on goodwill missions to Africa, Latin America, Europe and Asia. In 1983, she marked the 20th anniversary of the historic March on Washington by leading a gathering of more than 800 human rights organizations, the Coalition of Conscience, in the largest demonstration the capital city had seen up to that time.

Coretta Scott King led the successful campaign to establish Dr. King’s birthday, January 15, as a national holiday in the United States. By an Act of Congress, the first national observance of the holiday took place in 1986. Dr. King’s birthday is now marked by annual celebrations in over 100 countries. Mrs. King was invited by President Clinton to witness the historic handshake between Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Chairman Yassir Arafat at the signing of the Middle East Peace Accords in 1993. In 1985, Mrs. King and three of her children were arrested at the South African Embassy in Washington, D.C. for protesting against that country’s apartheid system of racial segregation and disenfranchisement. Ten years later, she stood with Nelson Mandela in Johannesburg when he was sworn in as President of South Africa.

After 27 years at the helm of The King Center, Mrs. King turned over leadership of the Center to her son, Dexter Scott King, in 1995. She remained active in the causes of racial and economic justice, and in her remaining years devoted much of her energy to AIDS education and curbing gun violence. Although she died in 2006 at the age of 78, she remains an inspirational figure to men and women around the world.

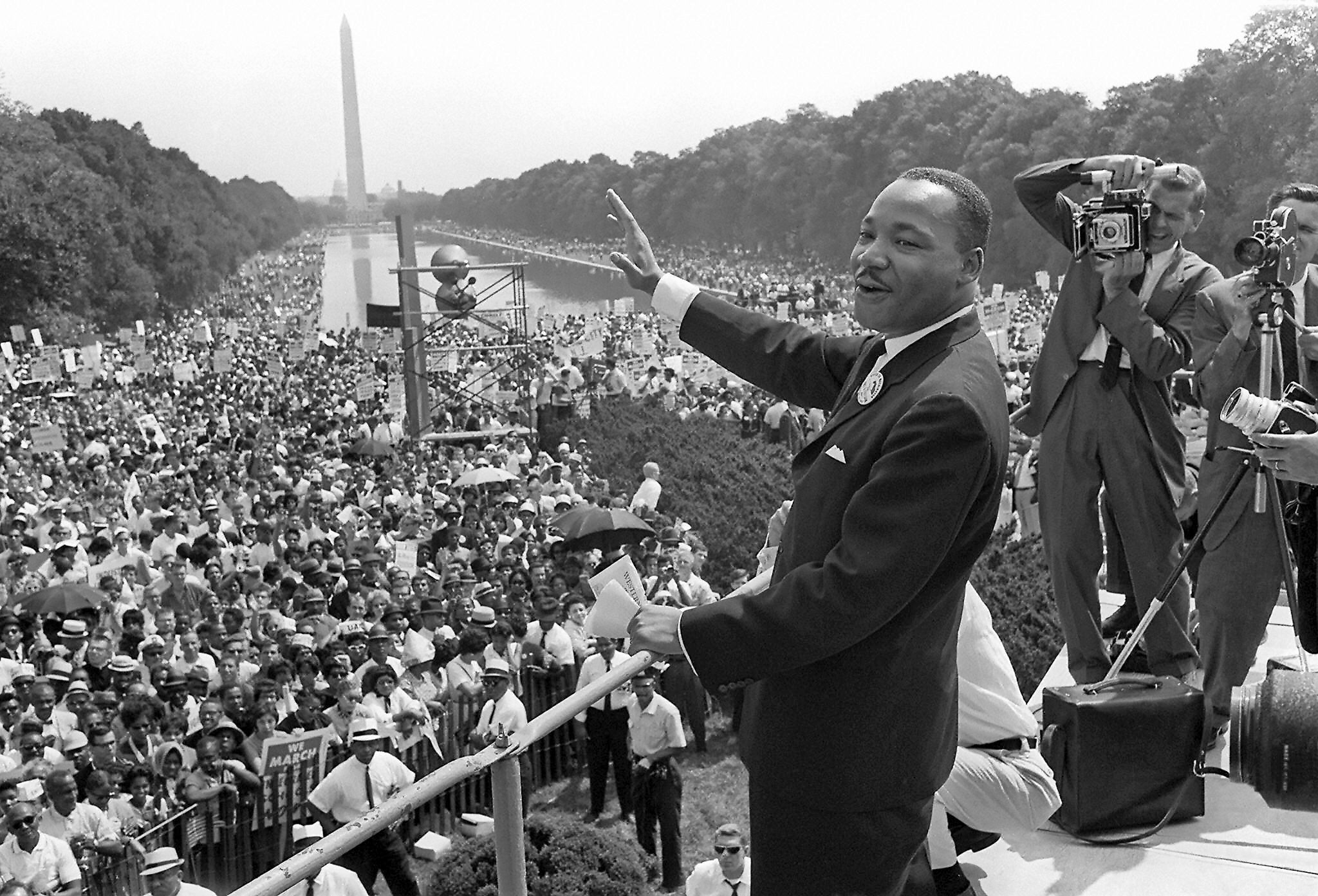

View and listen to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s historic “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered on the steps of Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., August 28, 1963.

Member of the American Academy of Achievement, poet and best-selling author, Maya Angelou shares her interpretation of Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

“When I went to the movies with other black children, we had to sit in the balcony while the white kids got to sit in the better seats below. We had to walk to school while the white children rode in school buses paid for by our parents’ taxes. Such messages, saying we were inferior, were a daily part of our lives.”

Young Coretta Scott’s gift for music and enthusiasm for education led her far beyond the segregated world of her childhood, but when she met the young Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the two resolved to return to the Deep South together and pursue the cause of justice in her own home state of Alabama. The Montgomery bus boycott thrust the young couple to the forefront of a revitalized civil rights movement, even as it exposed their growing family to the retaliation of those who opposed any change in the old system.

Braving death threats and surviving the bombing of their home by white supremacists, Coretta Scott King stood by the cause and her husband, from the Birmingham jail to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, from the March on Washington, to a stage in Oslo, Norway, where he accepted the Nobel Prize for Peace. After his assassination, she inspired the world with her courage, dignity and tireless devotion to preserving Dr. King’s legacy.

As founding President, Chair, and Chief Executive Officer of The Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, she saw that tens of thousands of activists from all over the world were trained in the philosophy and practice of nonviolence. She served as an advisor to freedom and democracy movements all over the world, and as a consultant to world leaders including President Corazon Aquino of the Philippines, President Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia, and President Nelson Mandela of South Africa. One of the world’s most admired women, she remained an outspoken champion of justice and human dignity to the end of her days.

(On June 18, 1999, Coretta Scott King addressed the American Academy of Achievement at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. Excerpts from her remarks on that occasion are interspersed throughout two video interviews — one from 1999 and the other from 2004.)

You were a music student in Boston when you met Martin Luther King, Jr. for the first time. Did you ever imagine that the two of you would play such an important part in the Civil Rights Movement?

Coretta Scott King: No, I didn’t.

I don’t think that my husband, although he said he was going to go back south and fight to change the system — and he was thinking about not just in Alabama or in Georgia, but he was talking about making our society more inclusive, changing the system so that everybody could participate — although he talked about that at that time, we never dreamed that we would have an opportunity, that we would be projected into the forefront of the struggle as we were. We were just going to work from, as he said, a black Baptist Church pulpit. That was the freest place in the society at that time, but we had no idea what God had in store for us. And I do believe it was divine intervention that we were thrust into the forefront of the struggle.

After we married, we moved to Montgomery, Alabama, where my husband had accepted an invitation to be the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. Before long, we found ourselves in the middle of the Montgomery bus boycott, and Martin was elected leader of the protest movement. As the boycott continued, I had a growing sense that I was involved in something so much greater than myself, something of profound historic importance. I came to the realization that we had been thrust into the forefront of a movement to liberate oppressed people, not only in Montgomery but also throughout our country, and this movement had worldwide implications. I felt blessed to have been called to be a part of such a noble and historic cause.

When Dr. King was asked to lead the Montgomery bus boycott, you had just had your first child. What are your memories of those days? What stands out for you?

Well, first of all, I was extremely excited about what was going on because this was something that had never happened before, and I knew this was history-making, and I also knew that it was not only happening in Montgomery but it was — the impact of this was maybe much further — much more extensive than Montgomery because during the Montgomery boycott we heard that there was a boycott in Johannesburg, South Africa of buses, and also there was one in Mobile and in Tallahassee, so it was like it was spreading but we also knew that the struggle was much bigger than a boycott. It was about the injustices in our society. It was about changing the society in such a way and changing the laws of the government locally, and certainly nationally we had to create new laws to protect us and protect the rights once they were won.

On a personal level, you had an extraordinary realization during the time of the Montgomery, Alabama bus desegregation court hearings. Can you take us back to that time in your life and express your personal concerns, but also the results of your soul searching?

We even experienced what was like modern day miracles when things happened. Like when the Supreme Court had ruled on bus desegregation, we were in court that day because the City of Montgomery was having a hearing and was trying to outlaw our transportation system and, if it had, maybe the people would have gotten tired and gone back to the buses. And my husband was very worried, and I said to him, “You know what? I think that by the time we go to court, and by the time the judge rules, that the Supreme Court will have ruled.” And we felt that if the Supreme Court ruled it would be in our favor and that was my consolation. Sure enough, while we were in court Associated Press — an Associated Press reporter handed a note to my husband and it said, “The Supreme Court of the United States has ruled today that bus segregation in Montgomery is unconstitutional.” So that ended the court session. So it was that kind of thing and intervention again that helped us to realize that we were doing the right thing, and we continued to do that, and more importantly that we had been called. I had been called personally to be in Montgomery at that time because I had always sought my purpose. As a teenager I began to think about what my life was going to be like and going to college. That was one level. Going beyond there was the next level. Going to prepare for a music career, but when I got to Boston there was, I realized, another reason for me being there. And then I wondered why Martin Luther King, Jr., a minister, that I didn’t think I would ever marry a minister, and then he was going back south, I wanted to go back south, but I wasn’t prepared to go at that time, because I had to finish my work, and finally in Montgomery — and then things began to happen and the house was bombed. So I did a lot of soul searching after that and tried to remember, you know, try to think back of how I got there, and I realized that all my life I had been being prepared for this role, and that we were supposed to be there in Montgomery. And it was a great feeling of satisfaction because I realized that I had found my purpose.

There were threats on your husband’s life, your life and your family. When did you realize that you would be dedicating your life to this movement?

I realized when Montgomery started that this was probably the reason we were called to Montgomery. After my house was bombed, and of course, all the threats on my husband’s life, on my life too. I realized I could have been killed as well — because I was in the house when the bomb hit the front porch — with my young baby. And the callers had been calling, and they said that they were going to bomb our house, told my husband they were going to bomb his house and kill his family if he didn’t leave town in three days. And of course he didn’t leave town in three days, and they did bomb the house. So knowing that they meant what they said, because they actually did bomb the house — the bomb was not strong enough to destroy the house, but if it had been, then that would have been very, very sad for all of us, certainly for me and my baby and my husband. But the fact is that I had to deal with the fact that if I continued in the struggle, I too could be killed, and that’s when I started praying very seriously about my commitment and whether or not I would be able to stick with my husband to continue in the struggle. And of course it wasn’t that difficult. It was a struggle, but I knew that we were doing the right thing. I always felt that what was happening in Montgomery was part of God’s will and purpose, and we were put there to be in the forefront of that struggle, and it wasn’t just a struggle relegated to Montgomery, Alabama or the South, but that it had worldwide implications. And I felt, really, a sense of fulfillment that I hadn’t felt before, that this was really what I was supposed to be doing, and it was a great blessing to have discovered this, and to be doing what was God’s will for your life.

After we were successful in desegregating the buses in Montgomery, the nonviolent revolution we launched in Montgomery spread like a prairie fire across the southern states. My husband led nonviolent protest campaigns against racism and segregation in cities across the South as well as in Chicago, Cleveland, and other cities in the North. During this time, I had three more children and participated in movement activities as much as possible. People asked me how was I able to do this and raise four children at the same time. I can only reply that when God calls you to a great task, he provides you with the strength to accomplish what he has called you to do. Faith and prayer, family and friends were always available when I needed them, and of course Martin and I always were there for each other. I learned that when you are willing to make sacrifices for a great cause, you will never be alone, because you will have divine companionship and the support of good people. This same faith and cosmic companionship sustained me after my husband was assassinated, and gave me the strength to make my contribution to carrying forward his unfinished work.

What inspired you? What kept you going?

Well, it was the belief that we were doing the right thing. Because it had never happened before, it was like, you know, the Supreme Court decision had been rendered in 1954, and this was in 1955, and we were all motivated by that and knowing that this meant the beginning of breaking down the system of segregation. We recognized that if the schools could desegregate, this means that other things can desegregate as well, so with Montgomery happening, it was like an intervention there that God had planted Rosa Parks and also Martin Luther King, Jr. And so you had the sense that something very, very significant was happening and that it had — it would have impact beyond — around the world that we were not only struggling to free the people of the South but oppressed people around the world. And we had no idea where it was leading but we had a sense that it was leading to something much more significant than what we were involved in at the time. And each time there was things — for instance, the stabbing incident when Martin was stabbed in Harlem. I mean, it’s like it made no sense except that God was preparing us for something even bigger. And then when the Nobel Peace Prize came along, which we were rewarded in a sense for our struggles, it was like, but this is still not it, because we have not achieved the peace that he was awarded — the award represented, but we still have a long way to go. So it was always not knowing what the future held, but we knew that we were on the right path, and you had a sense of, as Martin used to say, “cosmic companionship,” and that kept you going.

Someone else in your position might have felt that she had given enough, or sacrificed too much, and that someone else could carry the burden for a while. Why didn’t you feel that way?

When I say I was married to the cause, I was married to my husband whom I loved — I learned to love, it wasn’t love at first sight — but I also became married to the cause. It was my cause, and that’s the way I felt about it. So when my husband was no longer there, then I could continue in that cause, and I prayed that God would give me the direction for my life, to give me the strength to do what it was, and the ability to do what it was that he had called me to do. And I was trying to seek, “What is it that I’m supposed to do, now that Martin is no longer here?” And I finally determined that it was to develop an institution. I was already involved in building the institution, but I wasn’t sure that that was it. I thought maybe it might have been with women, but then, of course, I didn’t get that feeling in particular, but always, because I felt there was a need to have more women involved, in organizing them as a support group to my husband, and I encouraged him to do that. And he didn’t do that in particular, and I thought, well maybe then, that might be what I’m supposed to do. But then I finally determined that it was the King Center, because Martin’s message and his meaning were so powerful, and his spirit I felt needed to be continued. I know that people’s spirits live on, but I think in a very positive, meaningful way, that young people would know that that influence was being continued. So I felt that my role, then, was to develop an institution, to institutionalize his philosophy, his principles of nonviolence and his methodology of social change, and that’s what I have spent my years doing. For 27 years, I was the president, founder, CEO — I’m still a founder; you’re always the founder — but I retired from that position in 1995, and my son Dexter is now in that position, but I still continue to do all the work that I can, to reach as many people as I can with the message.