Have you ever looked back and wondered what that was about? The anorexia and these other difficulties?

Louise Glück: Oh, sure. Of course. Very complicated and probably not a subject for this inquiry. But obviously a sort of repudiation of my mother, whose will was overpowering, and whose sense of ownership of her young was very intense. I needed a way of pushing her away. And I also found unnerving the idea of beginning to have a body that was differentiated from other bodies. I wanted to be a pure soul, and I thought, “This is the most amazing strategy. I will become a pure soul. I will liberate myself from the constrictions and earthliness of flesh.” It was a great plan. The problem was that you die of it. And when I realized that, there was nothing in me self-destructive. I was trying to create a self. I just chose badly and I was awfully lucky that I had an analyst gifted enough to talk me down off the tree branch.

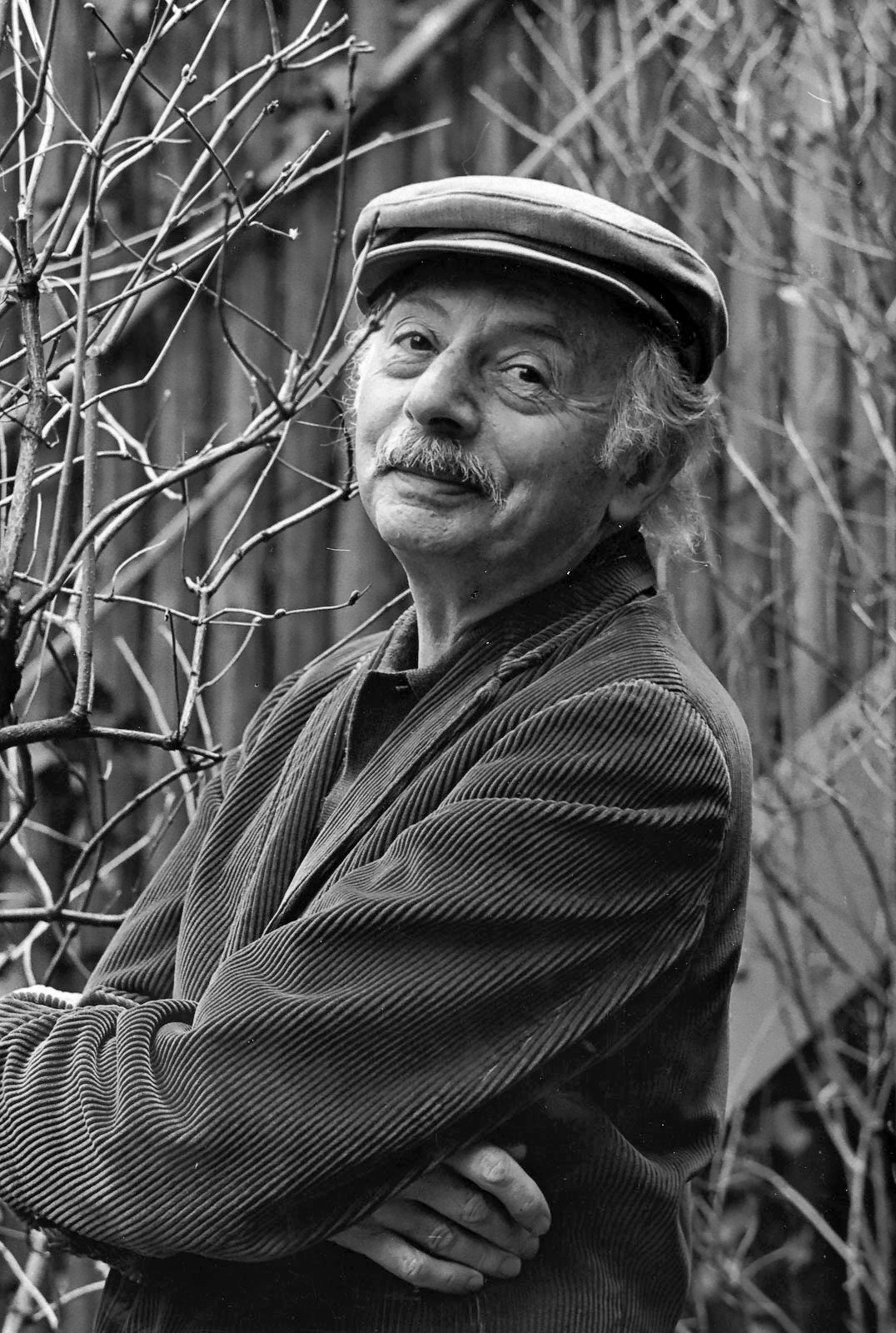

I started taking poetry workshops at that time, in night school at the School of General Studies, which was thrilling. So I had a world of people interested in what I was interested in. And I worked very hard. I had amazing teachers — very, very good at drawing out of quite disparate talents what was native to them. First, Léonie Adams, who used to smoke about eight cigarettes at a time. One would be burning its way toward her fingers and we’d all watch mesmerized to see if the ash would fall. Then she’d put it down and start another and there were these cigarettes burning all over the room. She was not a poet whose work I particularly revered — in fact, I didn’t know it until she became my teacher — but she was a very great teacher. She had about her an air of high seriousness and devotion that was attractive to me.

Stanley Kunitz the same. There was a sense of — you subordinated your ego to the needs of the poem. It was very attractive. And he didn’t teach it, but he manifested it, and we copied the idea of a kind of profound patience, and the capacity to be dissatisfied with something that one was doing for a very long time and still re-approach it. And also he taught — he somehow made clear — that we were going to need, besides patience, a very tough hide, because there are so many forms of humiliation. There’s neglect, which is the obvious one. There’s praise for characteristics that you think are not yours and that you deplore. To be praised for things that you deplore is quite punishing. There’s neglect, the kind that pats you on the head and moves onto the more interesting things. And all of it just cycles through. You ascend for a certain period. You can feel the pins moving on the board, and then all of a sudden there you are: target practice for people. And you have to just live through all of it, and not be destroyed.

Do you teach that to your students too?

Louise Glück: I try. I let them know that if they’re projecting onto me a kind of serenity of acknowledged accomplishment, that they’re quite mistaken, that that is not the experience of being in the world, and that it’s all struggle. The whole life is struggle and euphoria. And that’s why there’s daily life, which is an enormous consolation. You know, just the tasks of daily life: cooking dinner, gardening, going out with friends.

It sounds like poetry can be a somewhat tormenting pursuit.

Louise Glück: It’s often a torment, a place of suffering, harrowing. Things aren’t going well, things aren’t going well, and then things are great. And then struggle again. There’s a period of kind of tranquility after some large thing has been completed. It’s that wonderful point — many people talk about this — the moment of having written. And you don’t have to do it for a while. It’s very lovely. But then there’s a sense of the strangest anxiety, but anxiety builds. The sense that an account must be invented. I still don’t completely understand that. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about all these issues and talking about them.

You mean, why you need to keep writing?

Louise Glück: Yeah. Why? But I feel alive when I’m doing it and much less alive when I’m not doing it.

Joan Didion told us that she writes to understand who she is.

Louise Glück: I don’t know that I would put those words to it. I write to discover meaning. I want experience to mean something. It’s less a matter of who I am than that idea that nothing should be wasted. Something must come of it. Writing is a kind of revenge against circumstance too: bad luck, loss, pain. If you make something out of it, then you’ve no longer been bested by these events.

You said you sort of stumbled into teaching when you were having some tough periods of writing.

Louise Glück: Yeah. It was a miracle. It was one of the greatest gifts of my life. I had long thought that to be an artist involved — and I think there’s writers who make this case — the repudiation of the world. You channel all of these vital energies into only this one thing. You’re not distracted by pleasure or ordinariness. You don’t do any job that would use those same pieces of your mind. And that was, to me, temperamentally congenial. Repudiation was something I was very good at. So I lived in my 20s mainly fending off — not experience, because it was a time of great love affairs and so on — but professional work of a kind that would, I thought, draw on my vital juices. I was a secretary, which did not do that. But my writing life at that point was spent sitting in front of a piece of white paper at a typewriter completely paralyzed. And I would think, “I’ve got to write something,” and I would write “the” and then push really hard and “tree” would come out. But everything was dead. I had exhausted a mode of writing in my first book. I had no new sound to make. You had to hear first a message from the ear, a kind of sound, a phrase. I had nothing to go on. And I kept doing less and less, because I thought I wasn’t sacrificing enough, I wasn’t renouncing enough. Finally it occurred to me that I wasn’t going to be an artist, that this dearest wish of my heart would not be answered, and I thought I’d better think of something to do.

I had had offers of teaching jobs, one-semester, year-long things, based on my book. I’d turn them down because, “Poets shouldn’t teach.” I don’t know how I knew that. I don’t know where that came from, but it was a conviction. It was basically a sentence. A nervous sentence that began “Poets shouldn’t…” and then you could fill in any blank that was serviceable at the time.

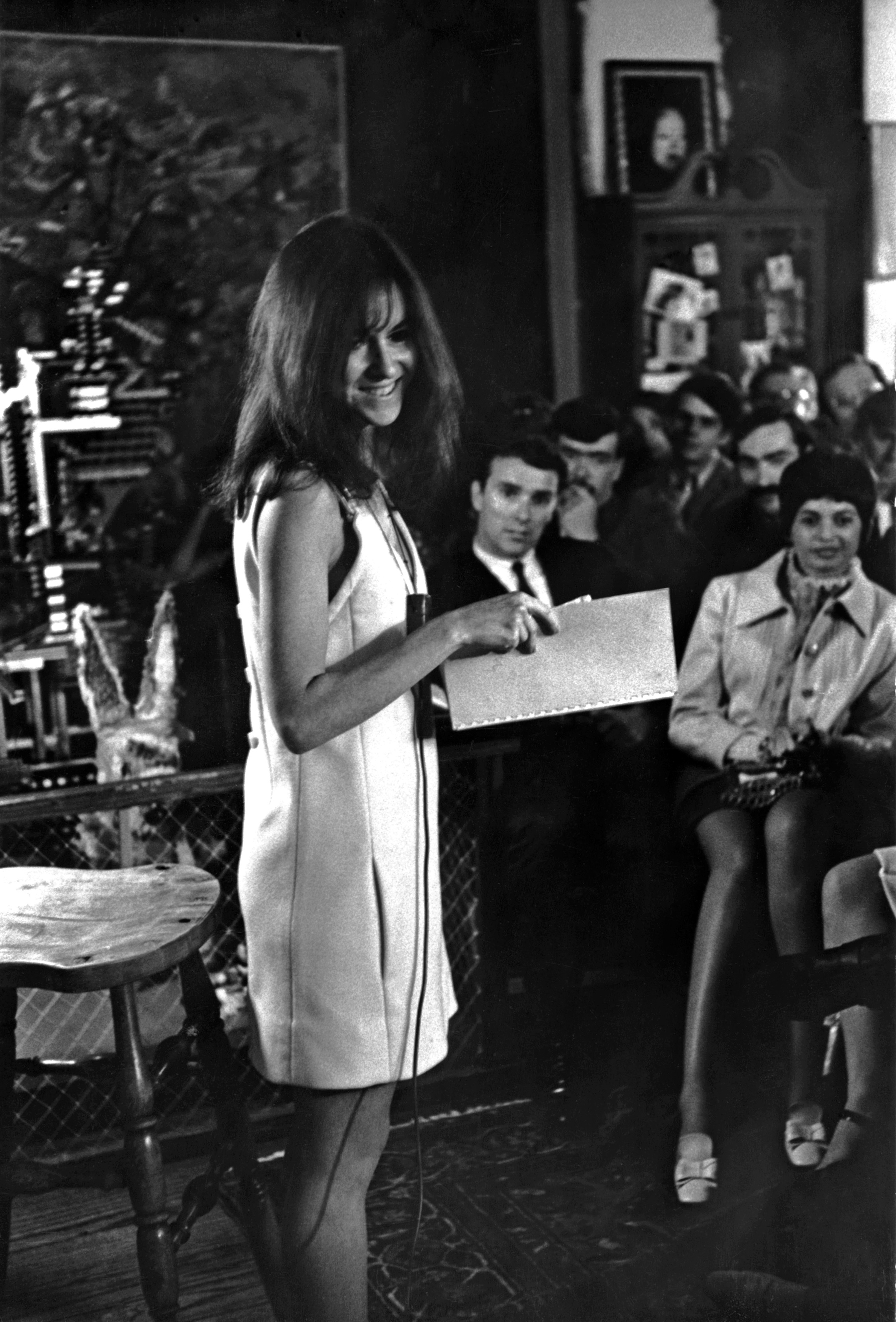

I was invited to go to Vermont to take part in a colloquium, and John Berryman was among those invited, and he was a hero. I wanted to meet him. And the minute I got to Vermont, I felt, “I’m supposed to live here.” And I had never had that feeling. Home to me wasn’t where I grew up, Long Island. It certainly wasn’t New York City where I then lived. And then it emphatically wasn’t Provincetown, where I lived for two years and was living at the time. But I got to Vermont, and I thought, “This is where I’m supposed to be.” And the people who were my hosts taught at Goddard College, a hippie institution back then. They kept saying at the parties during the colloquium, “You should come here and teach.” And finally I had an epiphany, and I said, “Yes.” I was so naive in this regard, I didn’t think that these English — I didn’t realize they weren’t empowered to offer me a job — they were just being pleasant. We were all liking each other. But I became then quite committed to the idea. And four days before the semester started, a job was found. One-semester deal. I moved to Vermont. I moved into a rooming house with a bathroom down the hall on what passed in Vermont for a highway, just maybe three-quarters of a mile from the school. And the minute I started teaching I became happy. I was happy in Vermont. My intuition was right. I think I know why, but teaching released me. It was one of the most dramatic transformative experiences of my life and entirely positive. I mean, having a baby was something like that, but it initially was terrifying and horrible. But this was simply — I loved what I was doing. I found my students fascinating, gifted. I was not much older than they were. I started writing. I started writing with a fluency I had never experienced.

What year was this?

Louise Glück: Gosh, late ’60s, early ’70s. It was before The House on Marshland. I started writing the poems that were in that second book, which are, I think, the first real poems I wrote, that weren’t just formal practices. That feeling about teaching has been constant. I still love teaching and I still love my students. Some of my students have gone on to very great careers of different kinds, which especially pleases me when we’re talking about undergraduates. There’s a poet named Claudia Rankin — brilliant, brilliant poet — who was in the first class I taught at Williams. I’ve known Claudia since she was 20 years old.

So there’s not a sense of rivalry or competition? You feed each other in a way?

Louise Glück: They’ll make me a better writer. They will. If they’re making discoveries, they’re hearing sounds I can’t hear — and reading their work I begin to hear — because there’s still lots that I can do for them. But I get excited by the freshness of their minds. There are a number of people my own age who have done or are doing extraordinary remarkable work. But I feed more on the young because of the sense of — the sounds they’re making are different — new — new to my ear.

Didn’t you once apologize to a former student because you thought you had learned too much, or taken something from him?

Louise Glück: Oh, no. It wasn’t a former student. One of the things I did later was I started editing a “first book” series, which was a discovery akin to teaching for me. I would get these cartons with a hundred and something books — finalists. And some of the judges for these competitions would ask to read ten books. I wanted to see everything that had, in the idea of the readers — screeners — some merit. And I copied a design Michael Collier had put in place for the Bakeless Prize — which I judged one year — of having the judge choose younger poets who would screen. And it’s terrific, because you have people then reading these books and making judgments about what to pass on, who are people whose sensibilities you trust. So when I started doing this for the Yale Younger Poets Prize, before I was a teacher at Yale, I had young poets screening for me. And I discovered in these boxes great artists. I mean, phenomenal artists. One of them was Peter Streckfus, whose rhythms and constructions were deeply in my mind. And I realized that I felt I was ripping him off. I went back and reread the book — this was some years afterward — and none of his language was — I mean, it wasn’t, but I knew where I had gotten what. I knew that I had gotten where I was because of him. And I called him, and I said, “I feel I must apologize. I hope that you don’t feel that these poems that I am writing are your poems.” And I said, “I checked,” and I said, “there’s no duplication of phrasing or even meter. I mean, they’re different, but I know.” And he said, “Oh, this is wonderful, Louise. This is what should be between poet, that there’s a kind of active cross-pollination.” I don’t know that I would be so generous. I’m very custodial. If I see a phrase of mine in someone else’s poem, I’m not happy. I want to write a letter to the editor — “I wrote that!” — but I don’t.

In one of your interviews you said that you don’t particularly have a sense of acclaim. That’s amazing when you look at the recognition you’ve received, the Pulitzer Prize and all of the major awards that you’ve won as a poet. Do they not sink in or is it just a temporary thing?

Louise Glück: I’m proud of them. And grateful. Very grateful. It’s helped me a lot. It makes my salary higher. The Bollingen (Prize) means something. That meant a lot, and I felt proud. But the problem is, if you get a prize and you’re not writing anything, or you’re writing stuff that seems so bizarre that you don’t know what to make of it, then your feelings about yourself as an artist are completely driven by, “Are you still an artist?” — that query, and the fact that you have been, or once were, or, “That book was good, but what have you got to show for yourself now?” The discrepancy is sometimes very painful. And a lot of prizes — the judges are just human beings and they have agendas and they have feuds and they have loyalties. If you know something about the world, it’s very — I’m sure this is true in other fields — you can see that so-and-so is getting this because the judge is actually ferociously jealous of someone else who properly should have gotten it. Nasty businesses like that. So worldly honor makes existence in the world easier. It puts you in a position to have a good job. It means that you can — or you could in a different economy — charge large fees to get on an airplane and perform. And for all that I’m very grateful. But as an emblem of what I want? What I want is not capable of being had in my lifetime. I want to live after I die in that ancient way. And there’s no knowing whether that will happen, and there will be no knowing, no matter how many blue ribbons I have plastered to my corpse.

What about the concept of a muse? Do you have any relationship with that word at all?

Louise Glück: Well, I hate the word, but it’s true that something sometimes visits and other times doesn’t. I wish I felt otherwise, but I feel as though there has to be some catalyst, some inspiration. All of a sudden there’s a phrase in your head. Where does that thing come from? I don’t know, and because I don’t know, I don’t know how to have more of them.

What do you hear in such a phrase? Is there a power to it?

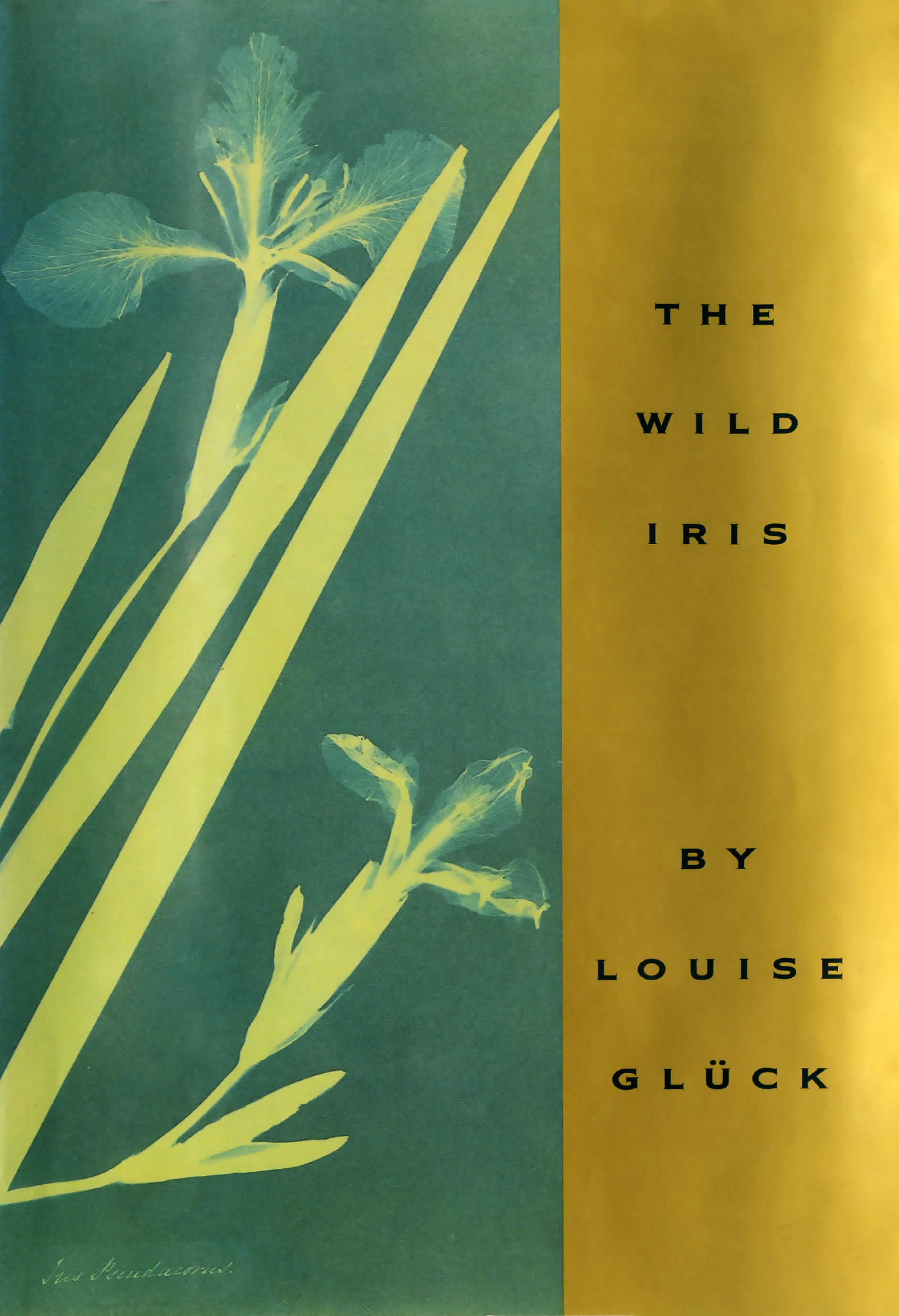

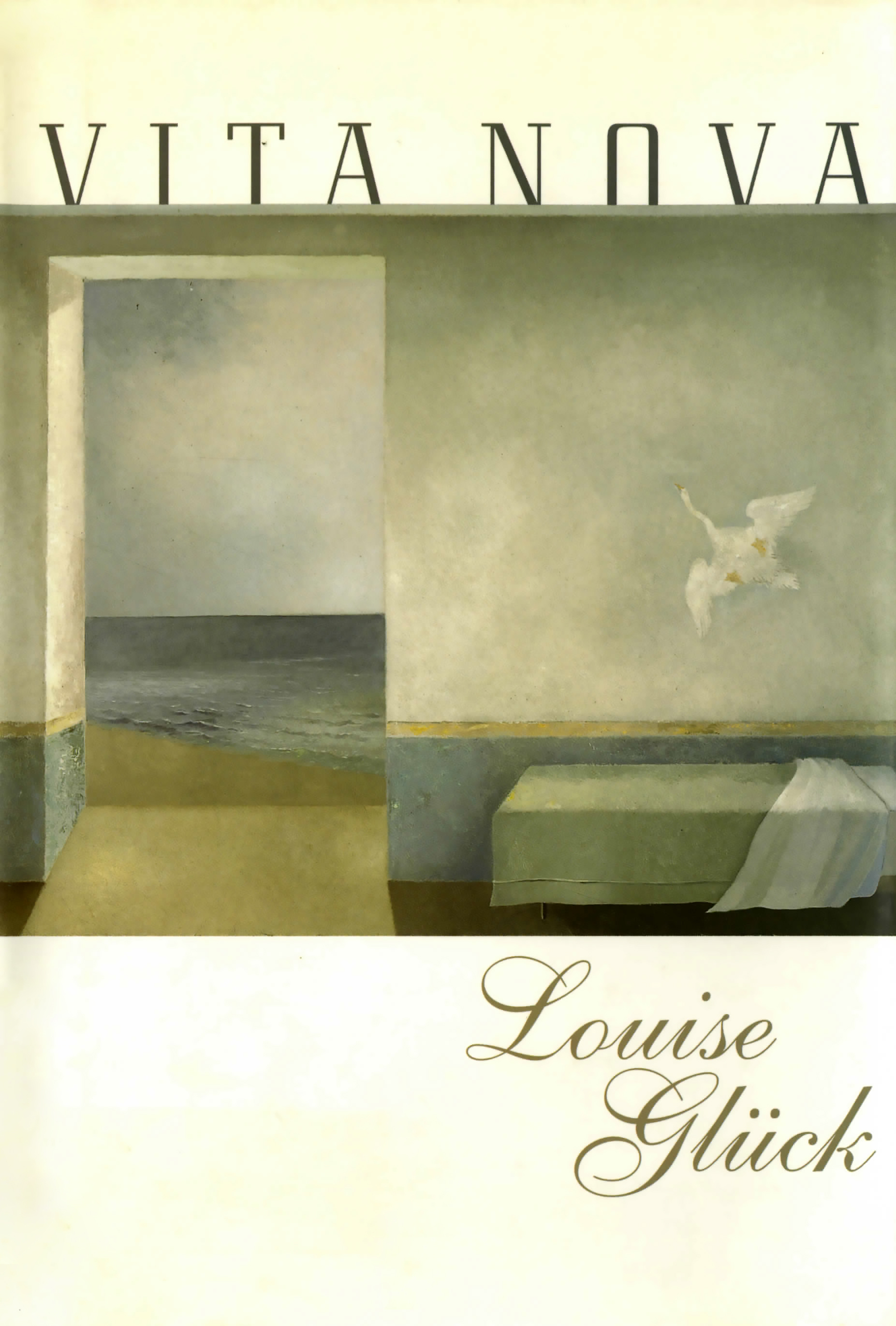

Louise Glück: Sometimes there’ll be lines in my head for two years before I know how to use them. I don’t know in what context what I hear can be liberated. So initially, they seem a great gift, because you have these two beautiful lines. And then they become a torment, because you have these two beautiful lines that aren’t in themselves a poem, and you have no idea what kind of house to build for them, around them. There have been periods in my life when my first thought in the morning has been that piece of language, my last thought at night the piece of language. But it’s like a whip. It’s a punishment, because I can’t do it. And then in each of those cases, ultimately I could write a poem that made a world. And every so often — after I was 50 I started writing books very rapidly. This happened in maybe four or five books. The Wild Iris was written — except for about five poems — it was written in six weeks, eight weeks. Vita Nova the same. The Seven Ages was written in something like six weeks. Just like four or five poems a day. And then the day before you start you’re a complete blank, and then all of a sudden six weeks later you have a book. And then you’re very tired and you get sick. And then some of the other — Village Life was different. Averno was written in two halves, the first kind of slow, dogged, hopeless. Then a hiatus of about two years, and then two years later the second half. Very fast. And then Village Life was sort of ideal. It was a steady writing for about a year, and a sense of great curiosity and contentment and richness, without any of the tempestuousness of that very rapid, “you give up sleep” thing. I know — I know it sounds like something that should be medicated, but it doesn’t feel like mania to me. It’s very specific to this one event. Anyway, it’s certainly not going on now.

What is not going on now?

Louise Glück: Writing at that kind of volcanic speed.

You must need to put a lot of trust in your muse, or your inspiration, whatever you call it.

Louise Glück: I think what I feel is trust in my editorial capabilities. I know that if I get something on the page, I can do something with it. I’ll know what to do. But yeah, I do. My bedtime story when I was very, very little, my father used to tell my sister and me the story of St. Joan, without the burning. And you know, she heard voices and I was very accustomed to the idea that one heard voices. I hear language. It’s not like an angel speaking to me, but language comes, and I don’t know how to control it, but I’m very grateful when it happens. I’ve never felt that I’ve been wrong about one of those little gifts. But then, a lot of what I do is not — it doesn’t come about that way. It’s a sort of “one poem leads to the next” in unexpected ways. But when some switch has been flipped and you’re in the “on” mode, and then you’re off. And every time it’s off, you feel as though this is the true silence. This is the end of all speech. It’s a horrible feeling, and it still dogs me. I’ve been talking a long time right now, for example.

You’ve said that music can play a role in writing your books. How does that happen?

Louise Glück: I start listening to something obsessively, and I do that even when I’m not writing. I tend to have something that I need to hear.

Is it a certain kind of music?

Louise Glück: It varies a lot, but mainly classical, mainly opera or song. This is my favorite of these stories, when I was first writing “Averno.” It was a poem I was working on, a sort of September 11th poem in multi-parts. I knew how I wanted the poem to feel because I’d been reading a murder mystery by Reginald Hill called On Beulah Heights. I read a lot of murders. The heroine of the book, you encounter her first as a child, and then she becomes a singer. She wants to do her own translation of Kindertotenlieder. The translation starts to weave through the text and it’s hypnotic. And that sound, Hill’s libretto that his heroine contrives, drilled itself into my head. It was in my head when I was working on these poems. I showed one of them to my friend Frank Bidart, who’s a very good reader, and he said, “You’ve been listening to Das Lied von der Erde.” And I said, “No, but I’ve been reading Reginald Hill on Kindertotenlieder. And he said, “You sound like Mahler.” And I said I didn’t have the music. I would never listen to Kindertotenlieder because it has such bad karma.

Songs of dead children.

Louise Glück: Well, everybody who had anything to do with it lost a child. I couldn’t afford that. But Das Lied von der Erde, Frank said, “We have to get you the record.” And we got a beautiful recording. I started listening to it and —

Which recording? With Kathleen Ferrier?

Louise Glück: Yeah. I have some others too, but that’s the one that I mainly listen to. I felt that that music was showing me how to write this book. Even the poems that don’t sound anything like it. And so I listened to Das Lied von der Erde all the time when I was home, every day, nothing else. And then I finished my book and now I can’t listen to it because I’ve over-listened. Years will have to elapse. There was a kind of correspondence that a good reader could pick up on.

With The Wild Iris I spent two years listening to Don Giovanni. Truly nonstop, which may have been hard on my family, because I was living with a kid and a husband at the time. And my only reading was flower catalogues. I was getting really passionate about the garden and I was writing nothing. And I thought — two years, two and a half years — I thought, “No wonder you can’t write anything. All you do is listen to Mozart and read about begonias.” What do you expect? And finally I thought — I didn’t know what to do, and I was walking in the garden and doing a little desultory reading, and I thought, “Well, I’ll try to write a poem spoken by a flower.” And immediately I thought — well, within two days, when I wrote another — I thought, “This — — I know what I’m doing.” And it was still Don Giovanni and the flower catalogues, but all of a sudden they’d fused into this form. But there was no sense building up to it of anything but a tragic falling off of original potential.

It seems like music provides an unconscious route to accessing your creativity.

Louise Glück: Yeah, but it has to connect to some preexisting neural code. Because not every piece of music does it. And then there’s music that I listen to obsessively that doesn’t do it. I spent a lot of time listening to Sam Cooke’s Song Book and that was all I could listen to, but it didn’t turn into poems and books, or it hasn’t yet.

A lot of scientists we’ve interviewed say there has to be failure in the laboratory in order for there to be success. Is that true in creative work as well? In poetry?

Louise Glück: I would say that not writing for two years is a very deep experience of failure. But I don’t know that it’s essential. I just know it’s my experience. It’s hard to say what’s essential. You tend to make a sort of case study of yourself, and the things that have been true of your life you generalize. But I can’t say that that kind of impossibility — that sense of stagnation and silence — I can’t say that they’re crucial. They seem to be what happens to me. I think, if failure and success are having to do with what the world says, that’s a whole other thing. There have been books I have been very — that I think of as among my best — that have been reviewed scornfully and deplored.

For example?

Louise Glück: Ararat. Now people fetishize it. You know, if they like my work, they’ll say, “Ah, Ararat. High point.” But at the time, where were they then? Not writing poetry reviews, that’s for sure.

You’ve written some essays about poetry. Have you thought about writing more prose, or even fiction?

Louise Glück: Never fiction. Fiction, for me, is like cooking. It’s pure pleasure. I don’t want to sully it by involving myself. And I don’t think I’m a storyteller. I like writing essays. It seems I have to be angry at something to write an essay. Though I’ve now written ten extended forewords, introductions to books by young writers. And I have about five or six other essays unpublished. I feel as though the balance is wrong. I don’t see a book in that. But I would like to write another prose book.

Whenever I’m working on an essay, I’m usually in a fairly good mood, the way you’re in a good mood when work is regular, and you’re thinking, and you have a desk and it has paper in it, and there’s words on the paper, and you go back to the paragraph before, and you take up the thread. That’s just lovely. But I don’t have any ideas for an essay now, and maybe I won’t write any more of them. The forewords kind of knocked me out. It was the only part of the judging that was really hard because I wanted to do — I wanted to do right by these poets. I wanted to say what was, about them, so distinctive and unique and important. And to do that year after year after year is very hard to even isolate. It’s easier to do it when you don’t like something, because all the reasons for your not liking something are immediately available to you. But when you like something, the vocabulary becomes very reductive. Things like “Wow!” “Lord!” “God!” Exclamatory and brief remarks don’t make a foreword. And that’s why a lot of these forewords that people write just say things like “Another important voice in American poetry.” Really? What kind? What sets it apart?

Do you read poetry for solace, or are there poets you keep going back to for different reasons?

Louise Glück: Reading poetry for me is so complicated now. I mean, if I love something, it makes me want to jump off a roof. If I don’t, I get enraged, not fruitfully. I tend to read fiction for solace. There are poets I never tire of. George Oppen, for example. Some of my early favorites. William Blake. I like austere language. But there’s some poets I love and can’t read anymore. Emily Dickinson is like chalk on a blackboard, or fingernails on a blackboard, whatever that figure of speech is.

Isn’t she also kind of terrifying?

Louise Glück: That doesn’t bother me. I like to be terrified. No, it’s not that it’s too harrowing or too scary. It’s the sort of insane maiden lady sound — kittenish. But she was one of my great heroes early on.

What about Yeats?

Louise Glück: He’s a very great poet, but do I read him regularly? No. When I read the poems, I think they have that feeling of having always been in the language. They’re gorgeous. I don’t like stadium poetry. I like, “Come closer, let me whisper in your ear.” Eliot or some perfect, strange thing like Robinson Jeffers’s short poems — “Vulture” — just great. But I read poems a lot of the time just because of how I live. I see a lot of them. I read a lot of poem books, some of which I think are brilliant. And I read a lot of work by young poets because it keeps me alive.

One would think that it would be very hard to teach or work with a young poet who’s saying, “Here’s how to do it better,” or “Here’s how to do it right.” I guess that also gets to the question of what poetry is.

Louise Glück: Well, you’re not doing anything like that. You’re trying to get the feeling of, “What is this?” What is the originality you feel on the page, if there is any. If someone’s really a beginner, then you simply try to isolate the moments when the poem seems alive, as opposed to inert. You know, if you can see from the first line where it’s going, and then it goes there, it’s a dead thing. It takes you nowhere you don’t know already. And if it does so in elegant metaphors, so what? This poem has already been written 3,000 times. But when you see something that is unprecedented, and if you can show the person that. So that’s one level of teaching, but then once people become really artists — young artists, but artists — it’s not doing it better according to some formula. It’s, “Where does the poem wilt a little?” Where is it the most conventional or generic, and can that moment be addressed and reinvented, so that that taint of the generic will be forever obliterated? It’s that that you try to do. It’s a fascinating problem, and different for every poem. To try to feel out what separates this from a memorable work of art, and how could it become that memorable work of art? It’s what you do on your own work too, but it’s the same thing with theirs, only they’re making a different kind of poem, a different kind of sound. It looks different on the page. Their concerns are different. So imaginatively, you enter the universe of that poem. And, in a way, you do that when you read great work. But there’s something wonderful about having that kind of immersion when the thing is still malleable. It’s thrilling, and poems can be transformed. And the students, of course, or young writers, get very excited when that happens. But every one of those books that I chose — and then sometimes worked on with the people — had different strengths, different problems. They were each utterly unique. Jay Hopler is nothing like Peter Streckfus, and neither of them is anything like Richard Silken. All those books had different problems.

Is creativity something that we all have and that can be fostered? In a certain sense, could we all be poets? Not Pulitzer Prize-winning poets, but is there poetry in everyone, do you think?

Louise Glück: I have no idea. I teach the people who come to me, and they come to me because they want to write poems. I think probably every 21-year-old has ten poems to write. What makes a poet is not just talent. It’s hunger, and it’s a hunger so profound and unkillable that it keeps you going for 50 and 60 years. You can’t know of a young writer if that hunger exists, and will it survive being mutilated, pissed on. There’s a mixed figure for you! You don’t know that. But you try to give them the skills that would be of use were that to happen.

What advice would you give to a young person who wants to write poetry?

Louise Glück: The same that anyone would say: Read poetry. Read. Keep yourself open to alternatives. But I think the problem with the question is that really it depends on the person. So your answer will be, to some extent, based on your perception of that person’s capacity. And hunger. And psychology. Some people are already reading so much that to tell them to read more, their voices will be drowned. They already are going to read more. They’re going to read every waking hour. So you remind them to live in the world. Actually that is something that I do say, because…

Sometimes people have in mind the kinds of renunciations I practiced myself, and instinctively am drawn to. Women who say they’re not going to have children, they’re not going to have professions, they’re not going to go to law school, they’re not going to go because they want to just write poems. And I think your poems — the ones that are yours and not skillful clones of existing poems — will come about through your having lived the life that most closely enacts your own passions. And if you spurn them, you’ll never write. I mean, you may write, but you won’t make anything. So I push them toward “yeses,” maybe more than I should.

That was very interesting. Thank you. It’s been great talking to you.