The exciting thing is to see somebody who is doomed to die, live and be happy.

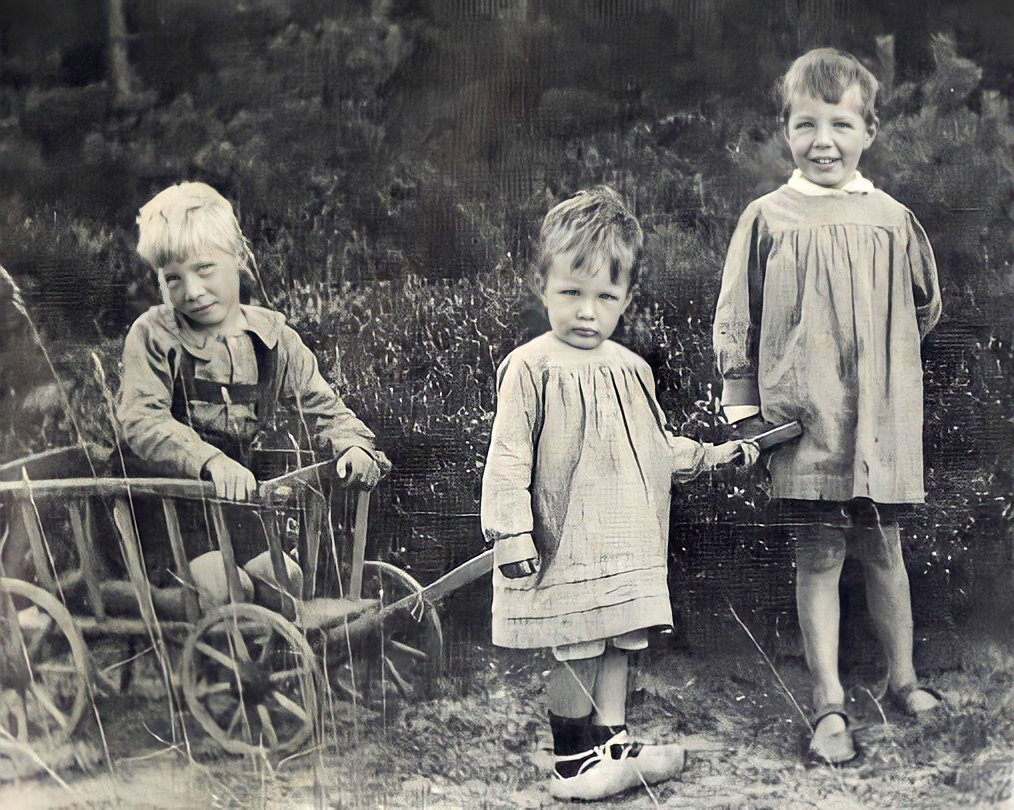

Willem Kolff was born in Leiden in the Netherlands. Kolff’s father was a physician, and young Willem decided at an early age to follow in his footsteps. He began his medical studies at the University of Leiden (one of the oldest in Europe) in 1930. From 1934 to 1936, he worked as an assistant in the pathological anatomy department of the university. After receiving his M.D. in 1938, Kolff began postgraduate studies at the University of Groningen, and served as an assistant in the university’s medical department. It was here that Kolff first became interested in the possibility of artificially simulating the function of the kidney, to remove toxins from the blood of patients with uremia, or kidney failure. He found a sympathetic mentor in Professor Polak Daniels, chief of the medical department at Groningen.

When Germany attacked the Netherlands in 1940, Kolff founded the first blood bank on the continent of Europe. When the Dutch defenses collapsed, Professor Daniels and his wife committed suicide. Unwilling to serve under the Nazi appointed by the Germans to replace his mentor, Kolff moved to the small town of Kampen, to work in the town’s municipal hospital. It was here, in 1943, that Kolff developed the first crude artificial kidney.

Working with wooden drums, cellophane tubing, and laundry tubs, Kolff constructed an apparatus that drew the patient’s blood, cleansed it of impurities, and pumped it back into the patient. The first 15 patients lived no more than a few days on Kolff’s machines. Kolff was not discouraged, however, because he was able to give a few more days of consciousness to comatose men and women on the point of death. Having crossed this barrier, he knew he would eventually be able to prolong a patient’s life even longer.

Kolff got his chance in 1945 when a woman in Kampen, a hated Nazi collaborator, was brought to him for treatment. Many people in the town urged him to let the woman die, but Kolff did not consider it his place as a doctor to determine who should live or die. His hemodialysis treatment saved the woman’s life, and he continued his development of dialysis machines.

In the years immediately following the war, he shipped free dialysis machines to researchers in England, Canada and the United States, completed his post-graduate work at Groningen — receiving his Ph.D. in internal medicine — continued his duties in Kampen, and lectured at the University of Leiden.

In 1950, he was invited to join the research staff of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation and emigrated to the United States. He became a U.S. citizen in 1956. At the Cleveland Clinic, Kolff turned to the study of cardiovascular problems and built one of the first heart/lung apparatuses. This device made open-heart surgery possible for the first time.

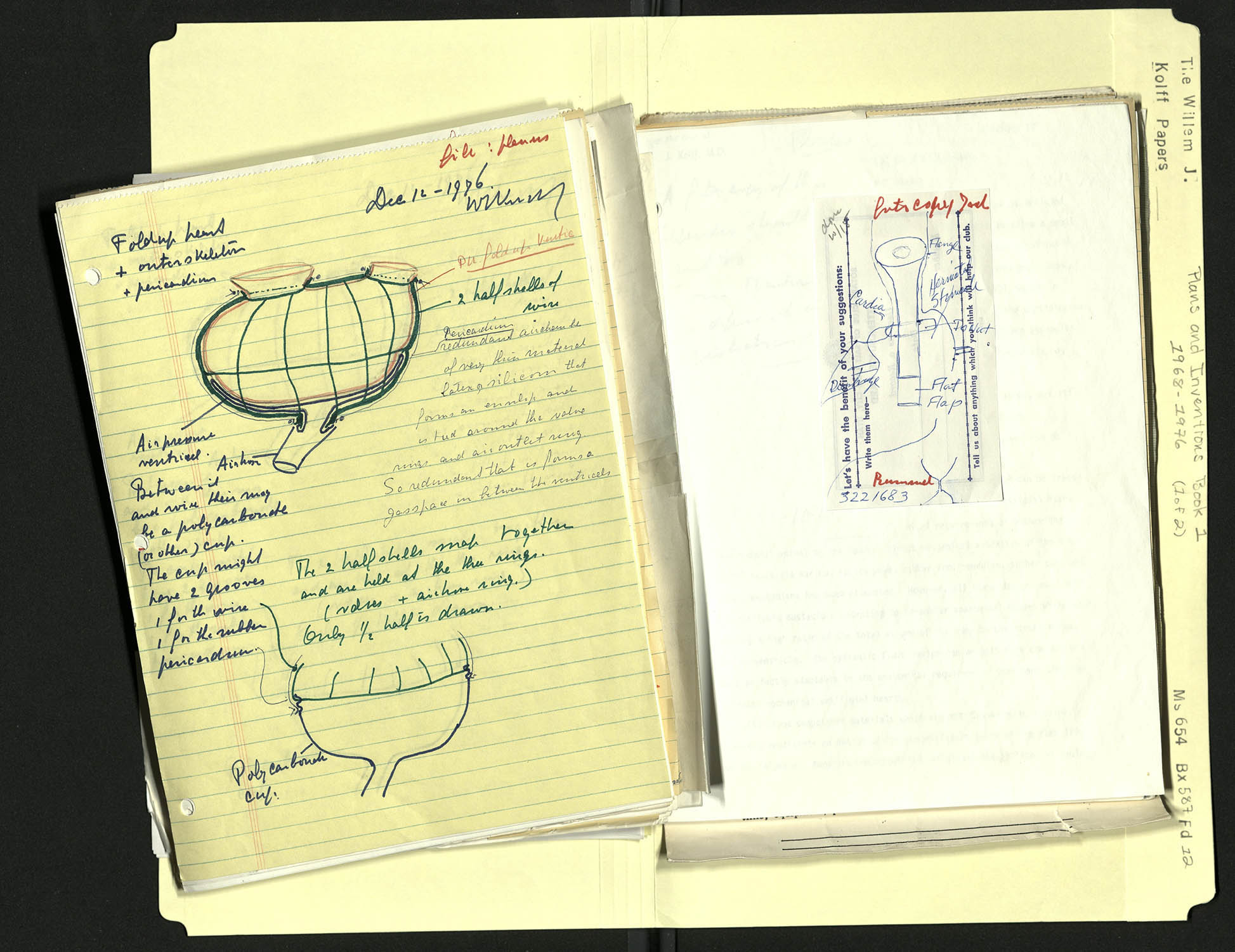

In 1955, he attended the first convention of the American Society for Artificial Organs. He now turned his attention to the development of an implantable artificial heart. In 1957, he implanted an artificial heart into a dog, which survived for 90 minutes. Kolff believed he was on the right track, although serious medical journals and societies would not accept articles on the subject of implantable artificial organs. By 1961 he had designed an intra-aortic balloon pump for cases of acute myocardial distress. Within a few years, this device was in widespread use.

In 1967, Kolff moved to the University of Utah as professor of surgery in the medical school, as research professor in the engineering school and as director of the Institute for Biomedical Engineering. Over the opposition of many physicians, Dr. Kolff wanted to give the patient more control of the process, so patients could perform their dialysis at home, without a doctor’s supervision. In 1975, he introduced the Wearable Artificial Kidney, an eight-pound chest pack with an 18-pound auxiliary tank.

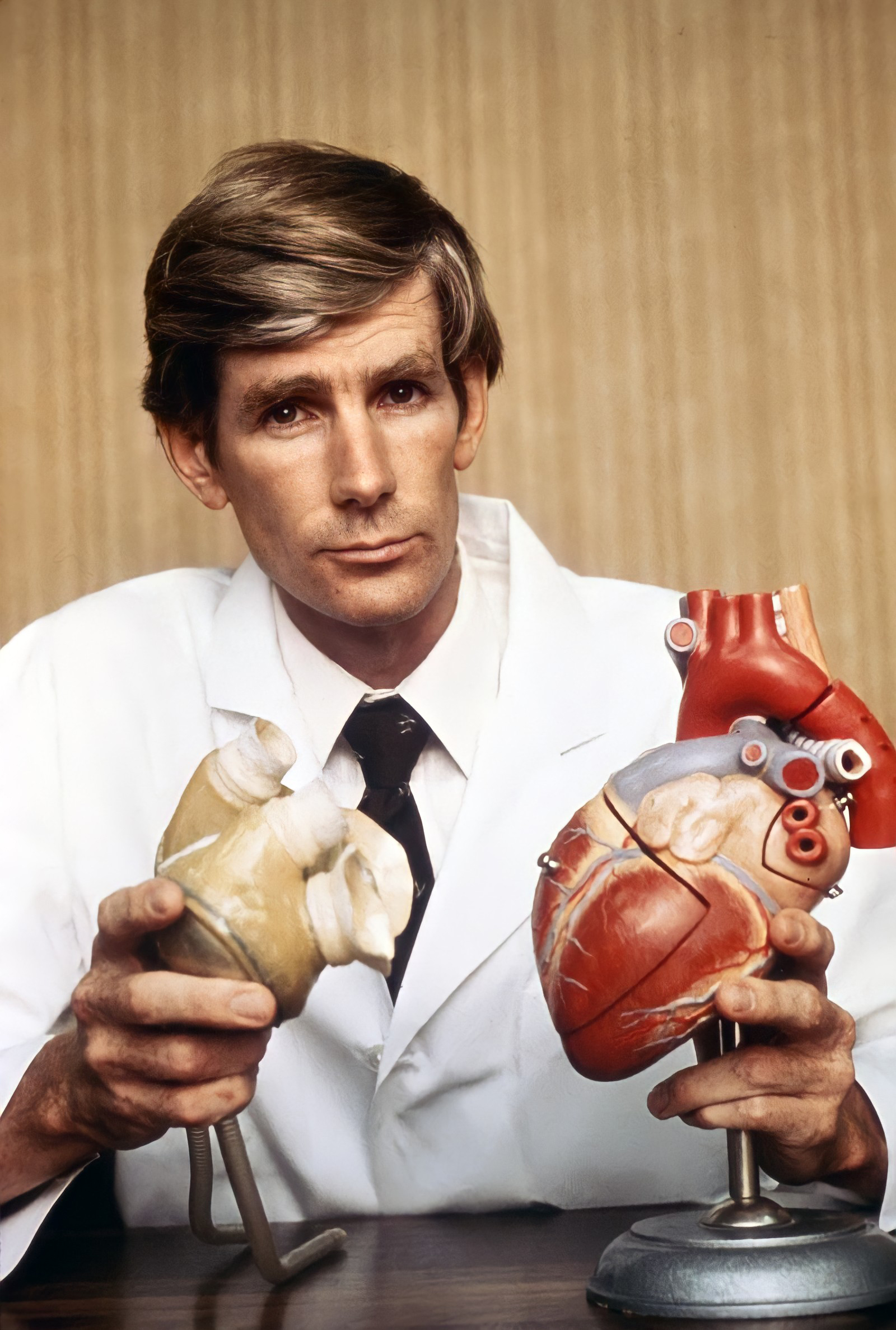

At the same time, Dr. Kolff continued his work on the artificial heart. With one of his students, Dr. Robert Jarvik, and a veterinary surgeon, Dr. Don Olsen, Kolff developed a series of progressively more efficient mechanical hearts. One of these, the Jarvik-5 mechanical heart, was implanted in a calf, which survived for 268 days with the device. In 1981, Kolff applied to the Food and Drug Administration for permission to attempt implantation in a human subject.

On December 2, 1982, a team of surgeons at the university, led by Dr. William DeVries, implanted the Jarvik-7 artificial heart into Barney Clark, a 61-year-old retired dentist. Clark required three subsequent operations to adjust the device and replace a defective valve but, when he died, almost four months later, it was due to the failure of his other organs. The Jarvik-7 was still functioning acceptably when Dr. Clark died. The publicity surrounding the operation and Dr. Clark’s subsequent progress made him a celebrity and focused international interest on Dr. Kolff’s research.

Although the increased success rate of human heart transplants has reduced interest in artificial hearts for the time being, Dr. Kolff’s accomplishment remains unparalleled. Over his long career, he published more than 600 papers and articles, and numerous books, including Artificial Organs. He was inducted into the Inventors Hall of Fame in 1985, and in 1990 was named by Life magazine in its list of the 100 Most Important Americans of the 20th Century.

Willem Kolff retired in 1997, after 30 years at the University of Utah. In September 2002, Dr. Kolff received the Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research, the highest honor in American medicine. The award committee cited Dr. Kolff for “the development of renal hemodialysis, which changed kidney failure from a fatal to a treatable disease, prolonging the useful lives of millions of patients.” He died at his home in Newtown Square, Pennsylvania, a few days before his 98th birthday.

“I wanted to make an artificial kidney that would save people. I was convinced that I could do it, and I clung to it until it was done.”

When Willem Johan Kolff began work on the artificial kidney, few medical professionals believed such a thing was possible. To draw a patient’s blood, cleanse it of toxins, and return it to the patient, seemed beyond the expertise of the most sophisticated medical centers. Dr. Kolff had no great resources to draw on. He was the sole internist in a small-town hospital in the middle of an occupied country during wartime. All materials were in short supply and local manufacturers were forbidden to do business with anyone but the occupying army. The first 15 patients to receive the treatment failed to recover, but Dr. Kolff persevered. The dialysis treatment he pioneered has saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of men, women and children, all over the world.

Dr. Kolff went on to design the heart/lung machine that made open-heart surgery possible. He has pioneered artificial eyes, ears and arms, and for 25 years led the effort to develop the artificial heart. In 1982, a heart designed under his supervision was successfully implanted in Barney Clark, an event that captured the imagination of the world.

Dr. Kolff, the process of renal dialysis — the artificial kidney — was one of your first major accomplishments. When did you begin work on this?

Willem Kolff: It was not the first thing, but it was the first really important thing.

When I was this young assistant at the University of Groningen my responsibility was for four beds, or rather the patients in four beds. That was all I had to do. And, one of these patients was a young man, 22 years old, who slowly and miserably died from renal failure. He became blind, he vomited, and it was a miserable death. And I, as a very, very young physician, had to tell his mother, in a black dress and a little white cap like the farmers have, that her only son was going to die. I couldn’t do a damn thing about it. So, I began to think, “If I could just every day remove as much urea as this boy creates, which is about 20 grams, then the boy could live.” Well, he died, but I began to work on that.

When I was at Groningen, I got interested in blood transfusions. I was the first in the Netherlands — and probably on the continent of Europe — to apply blood by continuous drip. It was not my invention; it was done first in England.

When I came to the University of Groningen, you had the donor lying there, and the recipient next to him, and you pumped blood from one to the other. But I introduced these drips, in the Netherlands. And then it became apparent that you needed to store blood. That led me to read about the blood bank in Chicago.

When the war broke out I happened to be in the city of The Hague, for the funeral of my wife’s grandfather. That morning of the funeral the German planes came overhead and they threw out leaflets that the Dutch should surrender, and they bombed the barracks, and so on and so on. And, instead of going to the funeral, I went to the main hospital, where I had been before, and I said, “Do you have a blood bank?” And they said, “No.” And I said, “Do you want me to set one up?” They said, “Yes.” And they gave me an automobile with a soldier in front because there were snipers, and they gave me purchase orders so that I could go to every store in the city and buy whatever I had to. And, in four days time I had a blood bank ready. That was my first major thing with blood. That blood bank is still in existence.

Some of these circumstances changed the whole direction of your work and your life.

Willem Kolff: Yes. Having handled blood outside the body made dialysis less difficult for me.

How did you come to leave the University of Groningen for a small city like Kampen?

Willem Kolff: I didn’t want to stay at Groningen because the Germans put a National Socialist (Nazi) at the head of the department. I stayed just long enough to get my certificate as an internist, a specialist in internal medicine. The night before this National Socialist appointed by the Germans came in, I left. I never saw him alive.

Then I had to look for a place, and I found one in Kampen. It was a very small hospital. They were very nice to me. They wanted to have an internist, and I was the first. I made the royal sum of 10,000 guilders per year in the first year. Divide that by two and a half, and you have the number of dollars that I made. I said, “Now I can afford to make an artificial kidney.”

Professor Brinkman at Groningen was the man who first told me about cellophane and dialysis. Brinkman was a wonderful man, and he knew cellophane. Cellophane tubing looks like ribbon, but it’s hollow. It’s artificial sausage skin, and it’s an excellent dialyzer. Dialysis means that if you have blood inside here, small molecules will go through the pores of the membrane to the outside where you have the dialyzing fluid. So urea and other products that the kidneys normally excrete will go out.

And another thing happens. Sodium chloride and other electrolytes will also go out. So, you add them to the dialyzing fluid on the outside, and they go out and in, and you get an equilibration through this membrane. If the sodium is too low, it goes higher; if it’s too high, it goes lower. This normalizes the electrolytes in the blood plasma. The treatment with the artificial kidney is relatively simple.

You didn’t succeed the first time you tried to figure out a solution to this, did you?

Willem Kolff: No, but I knew exactly what I wanted to do. I wanted to use dialysis to remove urea and other products that are excreted by the kidney. I filled a small piece of cellophane tubing, about 40 centimeters long, with blood. I added urea to it, I shook it up and down in a bath with saline, and from this I could calculate that I needed ten meters of this stuff, and that the blood had to be continuously in motion, and the dialyzing fluid also in motion. I also had Heparin to prevent clotting. All I had to do was to make a machine with sufficient surface area to make it worthwhile, and that’s what I did.

I went to see the director of the enamel factory. I got him interested, and he helped me. That was the first rotating drum artificial kidney. When it came time to pay the enamel factory, it turned out that the Germans did not allow any Dutch company to work for anybody else but the German Wehrmacht — that’s the army — so they never could give me a bill, and I never paid for it.

I had one patient with chronic renal failure that was in 1943, during the war. And, I dialyzed one-half liter of blood, and had it run through that artificial kidney and gave it back to her. And then waited two days to see if anything terrible would happen. Nothing happened. So I then took a little more blood, and so on. By that way, at that time, if either an institutional review committee for research on human patients — or the FDA — had been breathing down my neck, the artificial kidney would never have been made. Never.

You mean you worked in circumstances that allowed you to do this.

Willem Kolff: Yes, before the FDA was in existence and before IRBs (Institutional Review Boards). My conscience was my only brake. Otherwise, I could do what I wanted. But I had to explain to the patient what I was going to do, and I always did.

Dr. Kolff, can you tell us about the first patients you treated with dialysis?

Willem Kolff: Of the first 15 patients I treated with dialysis in Kampen, only one survived. And that one might have survived if I had used another sequence of treatment, without the artificial kidney.

Sophia Schafstad was the first patient where you can honestly say she would have died had she not been treated with dialysis. And she was in a prison right after the war, for collaborating with the Germans and many of my fellow countrymen would have liked to wring her neck. And, she was brought to us in renal failure. My duty is not to wring her neck, but to treat her. And we treated her. She was comatose when she came in. And after so many hours of treatment I bent over her and said, “Mrs. Schafstad, can you hear me?” And she slowly opened her eyes and said, “I’m going to divorce my husband,” and she did.

This woman was a National Socialist, and when I talked about her a few months later in London, I said, “It’s now been proven that the artificial kidney can save a life, but it’s not been proven that it’s of any real use to society.” The moral is that we have to treat patients when they need help, even if we don’t like them.

I’ve been mortally opposed to the so-called life-and-death committees that were instituted. When there were many more patients that needed to be dialyzed, and not enough artificial kidneys available, you had the institution of the life-and-death committees. You had a medical committee, and the first question they asked is, “Is this patient an emotionally mature adult?” If he was not, he didn’t qualify. And the next question was to the lay committee, in which sat two cleaning women, a minister, a banker, a union leader, and a lawyer. This lay committee had such questions as, “Does he go to church? Does he give to the community chest? Is he employed? Does he have children? Is he divorced?” Depending on the answer to these questions, he could be dialyzed. Otherwise, he could go to hell. I’ve been mortally opposed to that. When I set up a dialysis center here with a grant from some government agency, I was forced to put in a life-and-death committee, but it never met.

How was the artificial kidney received? Was there criticism? How did you handle it?

Willem Kolff: When the artificial kidney had become in my eyes a reality that did not mean that the medical profession was going to say, “Hurrah! Now we have something!” And, there were some that were receptive, there were many more that thought that the idea to have blood outside somebody’s body was a horrible idea, and they did whatever they could to prevent using the artificial kidney, and some of them wrote articles that said the artificial kidney was not needed. I’ve done one very good thing. I have never responded to any of those articles, for the simple reason that I had seen the improvement in patients so clearly that if I could just keep going, and have a few other people do it too, I would win.

If I had responded to unreasonable criticism, I would have made a lot of enemies. I would have become a paranoiac probably. Fortunately, I did not. On the other hand, when somebody tries to prevent me from doing something I want to do, I will do whatever I can to do it anyway.

Maybe I should show you now how much urea I have at one time removed from one patient. There was a patient who was comatose, absolutely comatose. He was a big man. And, this white powder is urea, and all this urea was removed in one dialysis, which is incredible, isn’t it? It goes very fast. And, in the beginning there were always people that said, “Well, urea is not toxic.” I would say, “Eat it, and see how you feel.”

How did you begin development of the blood oxygenator for the heart/lung machine?

Willem Kolff: We had seen in the artificial kidney that blood that was blue when it came in became red. So it was an oxygenator. It took up oxygen from the air. I began to make oxygenators. Blood oxygenators are used in heart/lung machines. That hospital (in Kampen) was too small for open-heart surgery. So I went to the United States, and one of the reasons why I left was that I had to be in a hospital large enough to have a cardiac surgical department. When I came here it was marvelous, three excellent heart/lung machines, but nobody in the United States was interested. I had to wait five years before the heart surgeon began to realize that he could not do all the surgery blindly.

How do you sustain yourself during that time when you’re far ahead and you’re all alone?

Willem Kolff: The first years in Cleveland were very, very difficult. Fortunately, I have many interests, so if I cannot make progress with the heart/lung machine, I can improve the artificial kidney. And I can also then begin this kidney transplantation, and that’s what we did. At that time when we entered the field of kidney transplantation, people did not use cadaver kidneys anymore. And, we proved that if we would take a cadaver kidney, put it in a patient without kidneys and dialyze them with one of these machines, that we could keep them alive long enough so that the cadaver kidney would recover from the rigors it had gone through when its previous owner died. That was very important, and also very fascinating and very beneficial.

Dr. Kolff, your work on the artificial heart attracted so much attention and discussion. Is it because of the old idea that a person’s heart is where their soul is?

Willem Kolff: Yes. The heart, as you know, is the symbol of love, the habitat of the soul, and the source of life. To replace that by a simple pump goes against everybody’s feeling. People are also afraid that if they have an artificial heart maybe they can’t love anymore. We had Barney Clark to prove the opposite. We knew that the artificial heart could sustain the circulation, because we’d seen it in animals many times. But Barney Clark proved that the artificial heart did not cause any pain, did not cause any disagreeable sensation. The click-click noise of the pump did not bother him. He still loved his family, he still had a very considerable sense of humor, and he still wanted to serve his fellow man. So all the essential things of the human mind were preserved. That’s Barney Clark.

Dr. Kolff, what are your memories of the Barney Clark surgery?

Willem Kolff: When that heart was put in Barney Clark, when it worked, I remember that I cried for a moment because I had started to work on the artificial heart in 1957, and this was 1982. So, you have to have some staying power if you do this kind of stuff. And then the publicity around it was incredible. They had to cordon off one-half of the hospital cafeteria, and there were seven television teams, if I’m correct and about a hundred reporters who camped there day and night. And, some of them tried to bribe personnel to give them information. When that became apparent, the vice president of medicine of the university gave a press release twice a day. Even then, reporters tried to get information from a resident, or a nurse, or a cleaning woman, or a janitor. So, don’t ever underestimate the enormous pressure that was on the people who put the heart in Barney Clark. Dr. DeVries, particularly, the surgeon, and others, including myself. Whatever happened during those days, I will forgive anybody, because the pressure was almost unbearable. When Barney Clark finally died after 112 days and we went to his funeral, there were helicopters overhead to film it.

Dr. Kolff, how would you describe what’s so exciting about the work you do, to someone who doesn’t really know anything about your field of work?

Willem Kolff: The exciting thing, of course, is not so much what people say about it, but to see somebody who is doomed to die, live and be happy. I got a letter three days ago from a woman who I’ve never seen. And she wrote me, “Dr. Kolff, I’ve been on dialysis for 18 years. You see here a picture of myself with my first grandchild. I’ve had a very rich life, a very full life, and thank you very much.” That is the reward, that of course makes you [feel] very good. And, that also sustains you to not pay too much attention to the detractors of what you’re doing.