You’ve seen a lot of changes in your lifetime. What was it like when you were growing up in Indiana in the 1920s?

John Wooden: In looking back, you would say it was difficult, but you didn’t think it was difficult at the time. I grew up on a farm. We lost the farm in the depression the year I was a freshman in high school. Then, we moved into this little town, Martinsville. But, while we were on the farm, we had no running water and no electricity and practically everything we ate, we grew. It must have been extremely difficult for my mother, with four sons and her husband, farmers, getting dirty all the time, my poor mother having to do all the laundry, hand washing everything and then cooking for all of those. But, we didn’t think it was tough at the time. When you look back on it, it looks very difficult, but we loved it.

Are there things you learned growing up that stay with you in your life?

John Wooden: Undoubtedly. We read more. There wasn’t television. There wasn’t radio, to speak of. We didn’t have it. Dad would read to us in the evenings. He read the Bible every day and insisted that we did, and he’d read poetry to us. I can still remember him reading “Hiawatha.”

“By the shores of Gitche Gumee

By the shining Big-Sea-Water

Stood the wigwam of Nokomis…

”

That encouraged my love for poetry. There were no athletic scholarships in those days, and mother and dad didn’t have financial means to help, but all four sons got through college. They worked their way through, and either majored or minored in English, every one of them. Every one became an administrator, all but me. I never became a principal or administrator, but I have a lifetime principal and superintendent’s license in the state of Indiana as well as a teacher’s license of English.

Tell us about your father, how he influenced your life and career.

John Wooden: Like Mark Twain, when I was young, I probably didn’t appreciate my father at all. But thinking back, some of the things he did became so meaningful. I didn’t realize at the time. For example, he tried to get across to us never try to be better than someone else. Learn from others and never cease trying to be the best you can be at whatever you’re doing. It doesn’t make a difference what it is. Just try to be the best you can possibly be. Maybe that won’t be better than someone else, but that’s no problem. It will be better than somebody else, probably, but somebody else is going to be better than that. Don’t worry about that. If you get yourself too engrossed in things over which you have no control, it’s going to adversely effect the things over which you have control. I can remember his trying to get that idea across, and I remember two sets of threes that he gave us. One was “Never lie, never cheat and never steal.” I’ve heard that since in different ways. The first time I heard it was from my Dad. The other one I never heard from anyone else was “Don’t whine, don’t complain and don’t alibi.” He tried to get those ideas across, maybe not in so many words, but by action. He walked it, let me put it that way. He was a gentle man, but physically strong, I think, but was gentle. As Mr. Lincoln said, “There’s nothing stronger than gentleness.” I think perhaps my dad emanated that.

When I graduated from the small country grade school, in the eighth grade, he gave me this little card, and all he said was, “Son, try to live up to this.” On one side was a verse that said,

”Four things a man must learn to do

If he would make his life more true:

To think without confusion clearly,

To love his fellow man sincerely,

To act from honest motives purely,

To trust in God and heaven securely.”

And, on the other side, was a seven point creed that I say I’ve tried to live up to. I haven’t, but I’m weak at times. One was “Be true to yourself, help others, make friendship a fine art, drink deeply from good books, make each day your masterpiece, build a shelter against a rainy day by the life you live, and give thanks for your blessings and pray for guidance every day.” I kept it with me until it had completely worn out. I still carry it around on a card, and always have it with me. Not the original that Dad gave me, because it just wore out, but one just like it. My father was a good person. I don’t believe there’s ever been a better person than my dad.

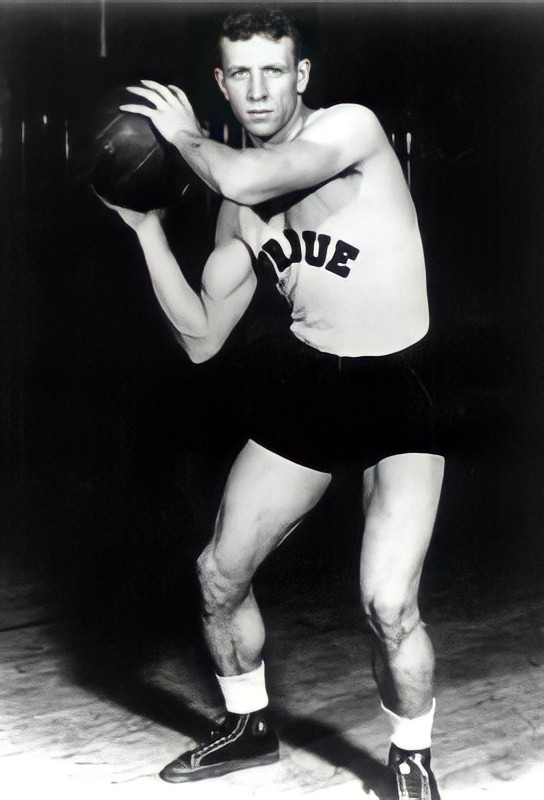

When did you start playing basketball?

John Wooden: In grade school. We had a little country grade school with an outdoor court, no indoor. We had to shovel snow off the court and play with no uniforms. We’d have a little thing we put over the bib of our overalls and maybe a different type of shoes, but not basketball shoes in the sense that we have now. But we had a grade school team and we played some other grade schools from around the area. Indiana’s crazy over basketball, in some ways too crazy. Then I went to Martinsville, which had a fine reputation, and we had great teams while I was there. As a matter of fact, we went to the state championship game in all three of my years in the high school. We lost it twice and won it once. Everybody there is crazy over basketball. This little town at that time had 4,800 people, and yet they had built a gymnasium the year before I entered high school that seated 5,200 and it was always full. People don’t believe me when I tell them about that here in California. Californians just don’t believe that, but it’s true.

You’ve coached and you’ve played a lot of sports. What is it about basketball that made it your game?

John Wooden: Baseball was always my first love. That’s my favorite sport. But, basketball, to me, is a greater spectator sport for a number of reasons. It’s played with the largest object. The basketball is larger. The spectators are closer to the action. They can follow the ball. You can’t always follow the baseball or the puck or the football, but you can follow the basketball. It’s a fast game. It’s a game of action. It has all the ingredients, I think, to make it a tremendous spectator sport. I think it is the best of all the spectator sports. It’s a team game.

I’m concerned about the basketball today, somewhat. I think it’s becoming too much showmanship and I don’t like that. If I want showmanship, I’ll go see the Globetrotters. In the pros today, the player that I’d rather see than anybody else is John Stockton from Utah, the all-time leader in assists. It’s not just because he’s the all-time leader in assists. It’s his demeanor. He’s a spirited player but never gets mad. He’s quick., he’s intelligent, he’s unselfish and he can do all things well.

I’ve had many fans while I was coaching, say to me now, “Of course, I don’t know anything about basketball, but…” And then, they’d start telling you what you’re doing wrong, or why aren’t you doing this, or why aren’t you doing that. And, the fact that they’re interested, that should never upset a coach. He should be pleased that they are interested. That shows that they are.

When did you realize that you had a talent for that game? What made you such an outstanding player, even as a youngster?

John Wooden: I don’t know. Just in playing with others, I seemed to do well. When I was in grade school, I seemed to do well. I would be one of the better ones, and in high school was one of the better ones, and in college one of the better ones. The Lord gave me some natural things. Perhaps in my coaching experience, I found out from my own personal playing experience that I didn’t have as much size as many, but I was quicker than most all, and that was my strength. So, in my recruiting, in all the years when I became a college coach, I’m recruiting for quickness. Now, you want a certain amount of size, but more coaches will give up some quickness to get more size. I would not. I would give up some size to get more quickness.

I hoped my forwards would be quicker than opposing forwards. I hoped that my guards would be quicker than opposing guards. I hoped my postmen would be quicker than opposing postmen. And, that’s what I’m looking for, and then I’m trying to incorporate that in making it into a team game.

It is such a team game. It’s a beautiful game when it’s played as a team. To me, it’s not beautiful when it’s individual one working one on one and going out and making a fancy dunk. That isn’t pretty to me. That may be what most of the fans seem to love, but I don’t.

Could you coach now in the same way that you did earlier in your career?

John Wooden: I see no reason why not, if you show those under your supervision that you really care for them. And that you’re interested in the group as a whole, but also in them individually. One of my favorite coaches, Amos Alonzo Stagg, once said he never had a player he did not love. He had many he didn’t like and didn’t respect, but he loved them just the same. I hope my players know that I love them all. There are times I didn’t like them. There were times I didn’t like my own children, but it never had anything to do with my love for them. If people want to be basketball players, if they know you care for them, if you’re not a dictator and if you make them feel that they’re working with you, not for you, I don’t know why I couldn’t today.

We’ve talked about the importance of your father. Who, besides your father, was an important influence in your life?

John Wooden: My wife, Nellie, my high school sweetheart. She helped me in so many ways. I suppose people today might say it’s hard to believe, but I was an extremely shy person. Maybe being raised in the country had something to do with it. She got me to go to take public speaking classes, which I probably wouldn’t have done. I know that was of great help to me. And then, in so many other ways. She was a year behind me in high school. I’ve got a picture of us when she was 15 and I was 16. I don’t know why but, when we met, it was just love at first sight. She is the only girl I ever went with. I was a year ahead of her and I went away to college. Then, she graduated from high school and worked, and we didn’t get to see each other that much because times were hard. Even though it’s only 70 or 80 miles from Lafayette to Burnsville, the bus might have been 10 or 15 cents. I didn’t have it and she didn’t either. We didn’t get together much but we knew as soon as I graduated and got a job, we would get married and we did. She was a tremendous influence in so many ways.

I’d say that my college coach, Piggie Lambert, is one of the most principled persons I’ve ever known. He had a lot of effect on my life. The head of the English Department at Purdue University, Dr. Creek, took a liking to me and tried to get me to forget sports completely and just concentrate on becoming a college English professor. There was some sort of a scholarship that he could get me for graduate school, but, I wanted to get married and get a job. So, I’d say that my father and mother, I don’t want to neglect my mother, and my wife and Piggie Lambert, my college coach at Purdue, probably had more influence on what I became as a teacher. That’s all I was: a teacher. That’s all I was as a basketball coach, just a teacher.

Are there any classroom teachers that you recall who influenced you in some important way?

John Wooden: Oh, yes. I remember my math teacher in high school, Dr. Roudebush. I remember him very, very well. And Katherine Burton, my Latin teacher, and, Herman Stalker, my science teacher. Various English teachers, Mrs. Phillips and Miss French and many of them I remember very well. Those were high school. They all, I think, affected me in different ways. I remember so many of them, far more than I do my college professors. My favorite teacher was in grade school. He was also the principal, Earl Warriner.

What about books? What books were important to you?

John Wooden: Poetry, the early English poets. I enjoyed the early American poets too, but the Victorian era poets I enjoyed very much, all of them. I enjoyed Dickens and I loved all of Shakespeare. I always loved his plays. In college one year, I had a whole semester of Macbeth and another whole semester of Hamlet. In high school I taught Hamlet and Macbeth and I only had two weeks. Just for pleasure reading, I have all of Zane Grey’s western books. I like them. Today, I try to get all of Leo Buscaglia’s books. One of my favorite books of all time is Lloyd Douglas’s, The Robe. I enjoy reading and I like pretty much all kinds.

I was looking through your bookshelves before you came in and I was struck by the fact that I didn’t find one book about basketball.

John Wooden: I’ve got a lot of books of basketball in the other room, and I’ve got a lot of biographies. I have biographies of coaches who were in the limelight, but also many of my favorite people. I’ve liked to study Mahatma Gandhi, and my favorite person in the world today is Mother Teresa. I’ve got a whole group of Lincoln books. He’s my favorite American. And books on Churchill and a lot of different people who have had a certain impact on civilization as a whole.

Where would you rank education in athletics?

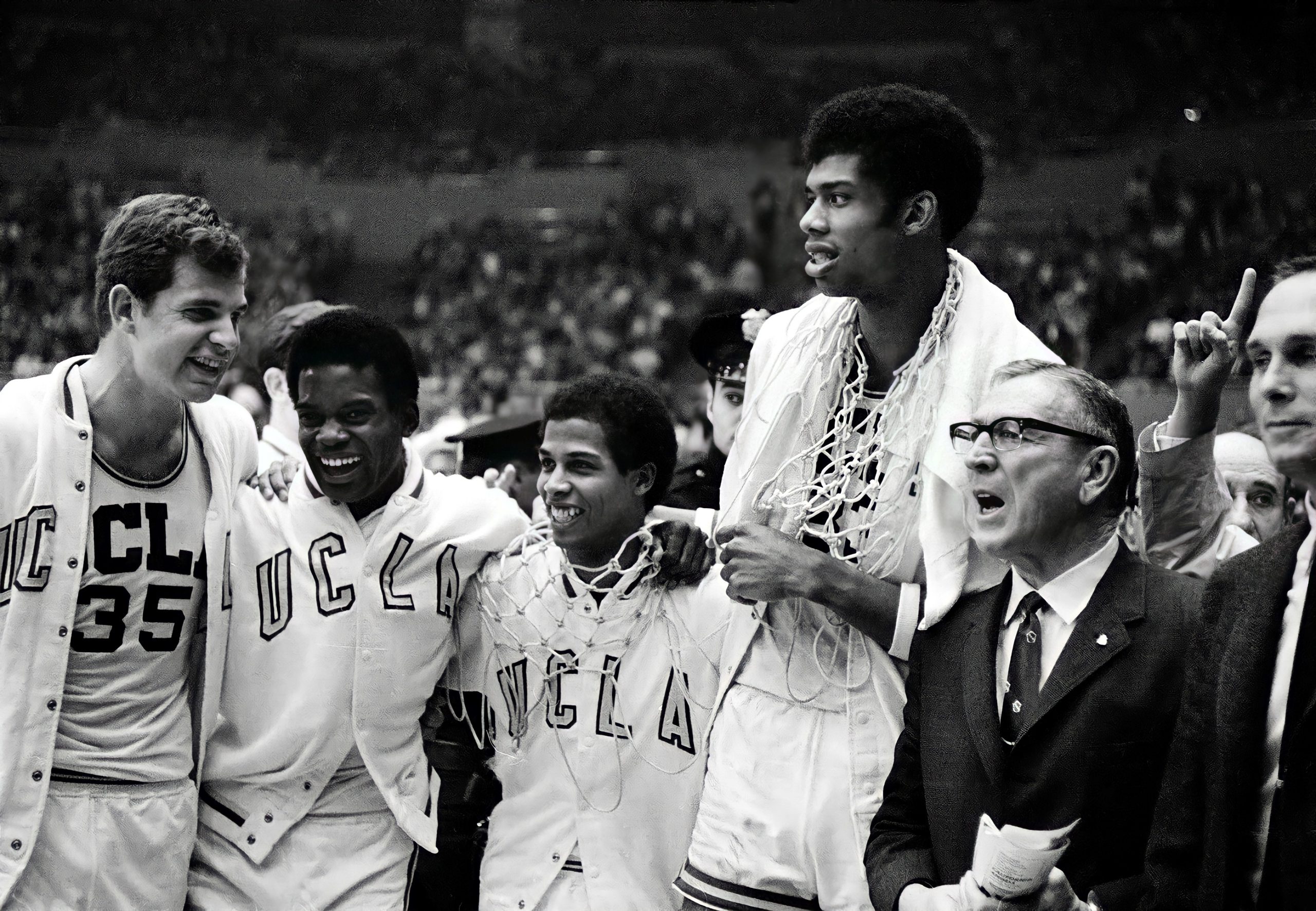

John Wooden: There’s too much leaning toward the athlete student, in my opinion, rather than the student athlete. One of the things I’m most proud of, in my years at UCLA, is that practically all my players graduated. Most of them did it in four years, when students today are taking five. Most of my players have done well in whatever profession they’ve chosen. Some 30 of my players became attorneys, some dentists, lawyers, eight ministers, teachers, just in all professions. It doesn’t make any difference what the profession has been. Practically all of them have been reasonably successful, and I don’t necessarily mean materially, but they’ve been successful in whatever profession they’ve chosen. That makes me very proud.

You have written about a high school teacher, Lawrence Schidler, who helped you think about the meaning of success. Can you tell us about that and how you define success?

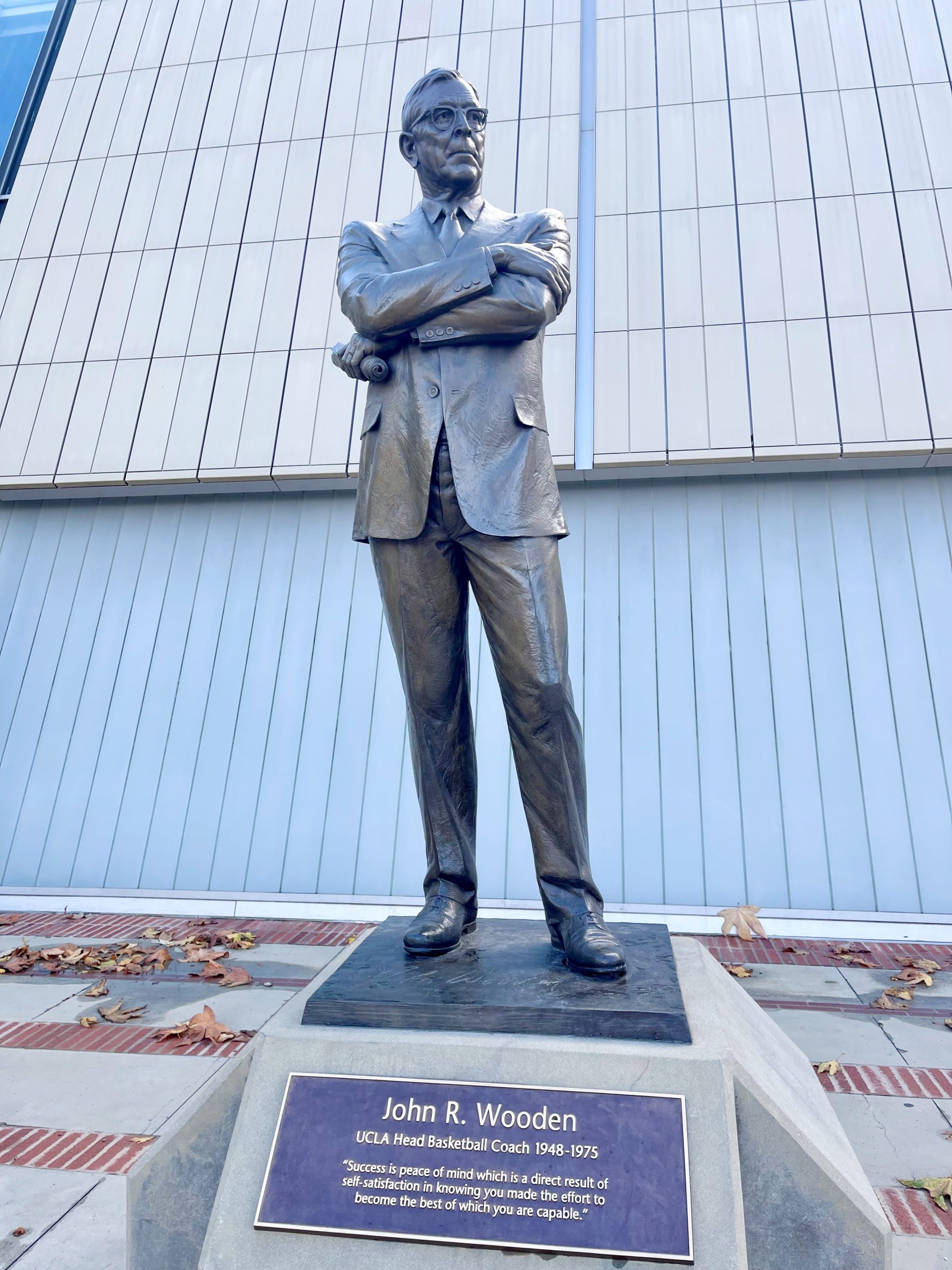

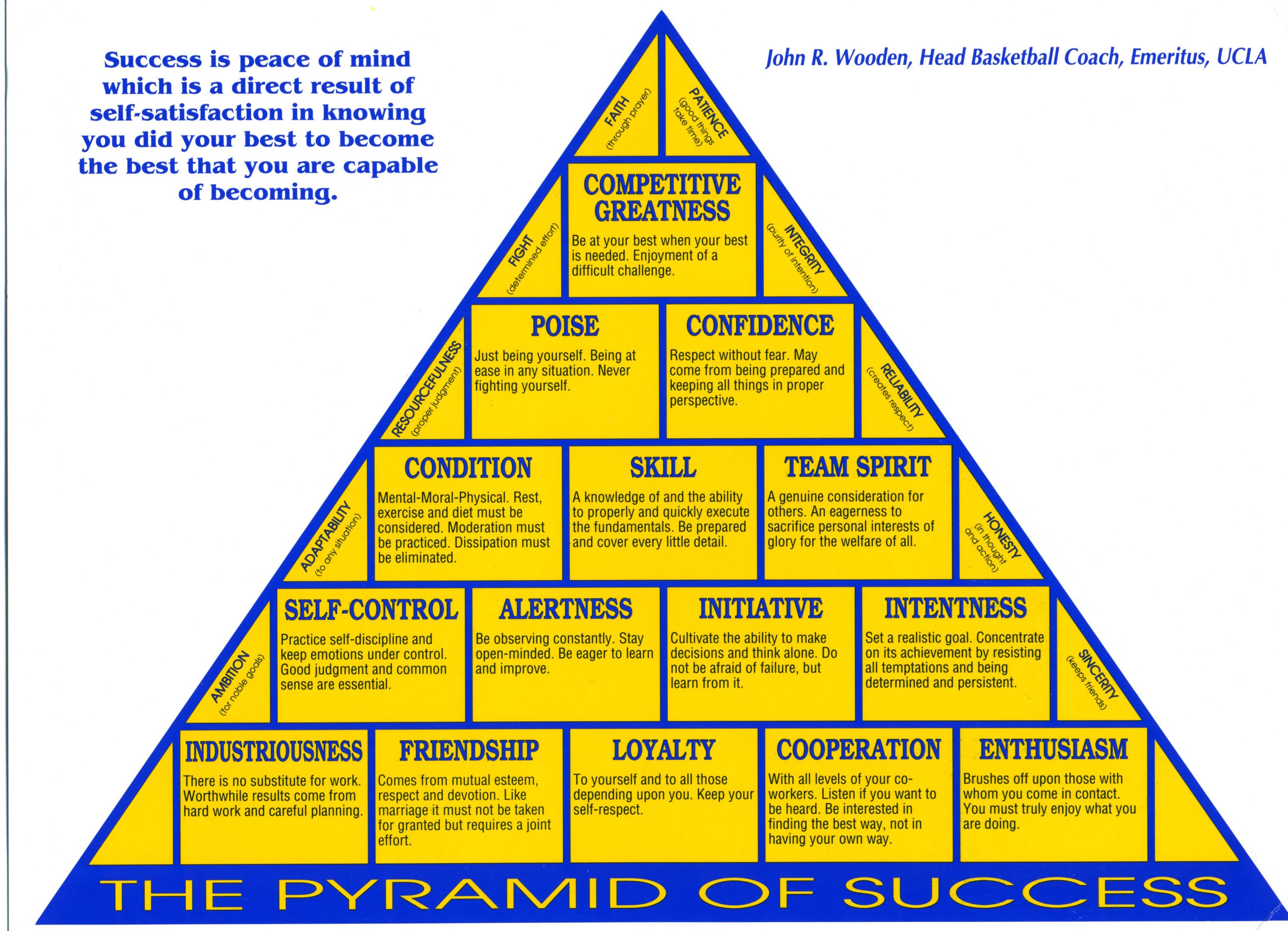

John Wooden: Lawrence Schidler was my math teacher, and he was very strict, but he made us concentrate. One time, he had us define success in class. I never forgot about that, the different definitions that various students have. After I had graduated Purdue and entered the teaching profession, I became a little bit disillusioned with what parents seemed to expect from their youngsters. If they didn’t get an A or a B, in one way or another, maybe subtly, they would make the youngster or the teacher feel that they had failed. They seemed to be very happy if the neighbor’s children got Cs, of course, they were average. But for their own! I didn’t understand that. I was very young. As I got older and had children of my own, I understand it a little better. But I didn’t like that way of judging any more than I like the way they judge athletic coaches and teams.

John Wooden: They use the winning percentage, and that’s not an accurate way of judging success. I wanted to come up with something of my own, and I think there were three things embedded into it. One was the discussion in Mr. Schidler’s class. Then, my dad’s words: “Never trying to better than someone else, learn from others, and never cease trying to be the best you could be.” And, always being interested in verse that makes a point, about that time I ran across a little simple one that said:

At God’s footstool, to confess,

A poor soul knelt and bowed his head.

”I failed,” he cried. The master said,

”Thou didst thy best. That is success.”

I think those things, more than anything else, accounted for my own definition. The definition I coined for success is: Peace of mind attained only through self satisfaction in knowing you made the effort to become the best of which you’re capable. Now, we’re all equal there. We’re not all equal as far as intelligence is concerned. We’re not equal as far as size. We’re not all equal as far as appearance. We do not all have the same opportunities. We’re not born in the same environments, but we’re all absolutely equal in having the opportunity to make the most of what we have and not comparing or worrying about what others have. I coined that in 1934. Later, I started working on my pyramid. I worked on that for the next 14 years, placing success according to my definition at the apex.

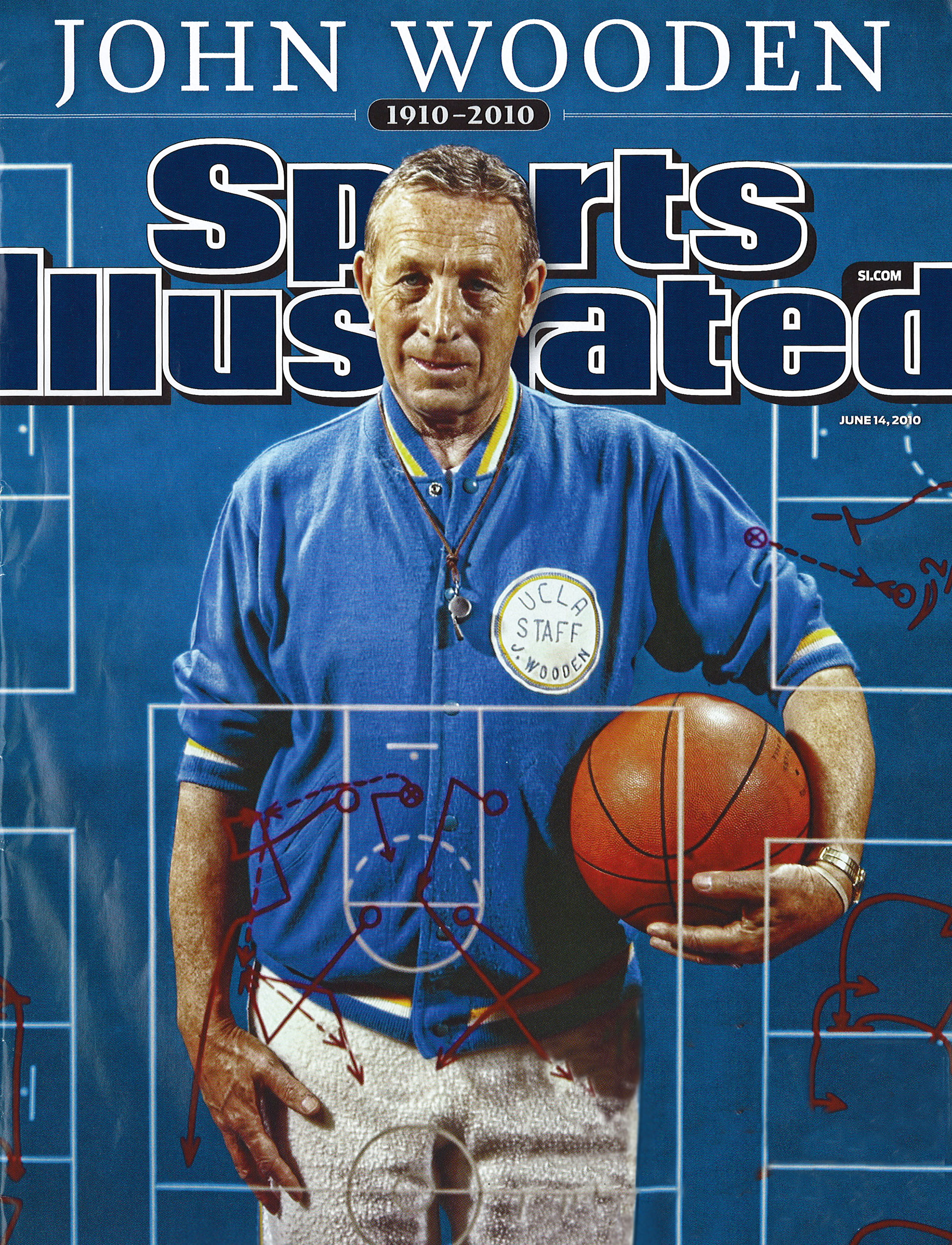

Most of us watched UCLA’s basketball teams and thought about you as a coach, as a high-powered molder of teams, but you saw yourself as a teacher.

John Wooden: I was just teaching basketball rather than English. It’s different in sports. In my English classes, it’s mental and, to some degree, emotional. In basketball or sports, it’s mental, emotional and physical. In some ways you get closer to them. When I was in the service in World War II, I had a lot of letters from athletes that had played on my basketball or baseball or tennis teams in high school, all optimistic. Some of them never came back, but they were very optimistic, no complaining. I didn’t have very many letters from my English students, and I had had a lot more English students than I had athletes. I didn’t have that many athletes, but you get closer to them. I love to teach English, but you get closer to those under your supervision in sports, I believe, than you do in just the classroom.

What about all the hours of preparation and practice? That’s something a lot of young people today might not be thinking about.

John Wooden: In anything, failure to prepare is preparing to fail. Like one of the points in the seven point creed that my dad gave me was “Make each day your masterpiece.” Now you’re not going to make great improvement in one day. But if you miss out one day, you’ve lost a little bit. You’ve got to build up a little each day. It’s little things that eventually become big things and make big things happen. It’s building up on the little things, and youngsters must understand that. I believe a little different than many coaches, as a matter of fact. I wanted my players — and tried to get this across to them — when you come on the basketball floor each afternoon, for the next approximately two hours, you are a basketball player. That’s all. I am looking at you and thinking of you as a basketball player. That is all. As soon as practice is over, you are not a basketball player. You are a student at UCLA. Now you better keep that in mind. You’re a student. That’s the reason you’re here. Basketball may be, in most of your cases, given you a scholarship and it’s paying your way, but if you start putting basketball ahead of your academics, you’re not going to have either very long. Or you must have, everyone must have, a certain amount of social activity. But if you put social activities ahead of your academics or your basketball, you’re not going to have any of them at all before very long. At least you won’t have here. So I think that that must be stressed, because it should be the student athlete, not the athlete student.

What is it about coaching that’s meant so much to you over the years?

John Wooden: The rapport that you have with so many youngsters. Hardly a day goes by that I don’t get a call or a letter from someone who was under my supervision in the past, going back to my very first years at UCLA, and going back to when I was at Indiana State, some even going back when I taught in high school. That’s the relationships that you have because of the way you’re working with them, more than just from the mental aspect, you get closer to them. They become almost like your children. Next to your own flesh and blood, you get very close to them. Their joys are your joys, their sorrows are your sorrows and that goes on forever. It doesn’t end when they leave your supervision. That’s with you forever. I can name almost all of the basketball players who played for me, even going back in high school, but I can’t begin to name all of the English students I had.

It’s clear that you see coaching as a responsibility. What is the main responsibility of a coach?

John Wooden: You must set an example. Your players must know that you care for them more than just as athletes. Certainly, they understand that they are there because of their athletic ability, speaking of college. That’s why they’re there. That’s paying their way. But when you have them under your supervision, it’s up to you to make sure that they understand that you care for them as individuals. As I mentioned — his name was Alonzo Stagg — said, he never had one he didn’t love. A lot of them he didn’t like, couldn’t respect. But he loved them just the same. He also said that you couldn’t tell whether you had a successful season until 20 years or so after they’ve graduated. There’s a lot to that, too. If your players come to the belief — which they won’t know when they first come to you, it will be your actions that determine this — that’ll be what will determine this. It won’t be from the things you say. That will have some influence, yes, but are you walking it or just talking it? You can’t fool these kids. It should be your responsibility to lead them in a way that’s going to be beneficial to them all their lives, not just through their athletic days. I really think most coaches do that. I think most do, not all, no. But not all doctors are as ethical as they should be, not all attorneys are as ethical as they should be, not all businessmen are as ethical as they should be, but I believe the vast majority are.

In your first year at Indiana State as coach, you and your team were invited to the National Tournament and you didn’t go. Tell us about that.

John Wooden: I had an African American boy on my team. He wasn’t a starter. He was probably the twelfth man on a 12-man team. He didn’t get to play very much, but he was a member of our team and dressed for every game, was with us for every game. They did not permit black players to play in the National NAIA Tournament at that particular time, so I refused the invitation because of that. Now the next year, since that first year I was at Indiana State, I had 11 freshmen and one sophomore on that team, so I had them all back the next year. No one beat anybody else out. I still had the same 12 players the next year and we were invited, again. We had a better year. We’d had a good year the year before, but that next year we had a really better year. We were invited again and I refused. But through this youngster’s parents, and through the NAACP, they felt it would be a good thing, that it might open the doors in a sense. I was persuaded to do that, to take him. He couldn’t stay in the hotel with us. He could eat in the hotel if we ate in a private room. He couldn’t eat in the dining room. So we had our meals in a private room and he stayed with a black minister and his wife in Kansas City. He would sit with us in the game and we had no problems. He was accepted. There were no problems at all. But he was the only one; he was the first one. But I know in driving from Terre Haute to St. Louis, we stopped some places in Illinois maybe to eat, they won’t let him in. So I would leave. “You take us all or you don’t take any.” Then we’d go someplace else and get some things and take out. It’s good that times have changed. I’m proud of the fact that, I think in some ways maybe I helped bring about some changes. There’s way too much prejudice in this world, not just in race, religion and other ways. Anything anyone can do to help it, even if it’s just a little, that’s good. Because there are a lot of us, and if everyone would help just a little, that could be a whole lot. It’s like we are many, but are we much? We’re not much until we all contribute to some degree.

Indiana, when you were growing up, was the home of the Ku Klux Klan.

John Wooden: That’s correct.

How do you explain that decision that you made?

John Wooden: I think that’s one of the things my dad tried to teach us: You’re as good as anybody, but you’re no better than anybody. Don’t expect privileges at all, in any way. I think, maybe from that, we saw no color. As an athlete in college, there were hardly any black athletes that I played against. The same thing in high school. My first years of teaching in high school, I had no black athletes, but later on a lot of them. It was just my upbringing that you never looked down on anyone for any reason at all, and certainly not race or religion.

In general, how have you dealt with difficult decisions, whether they had to do with athletes on your teams or your personal life?

John Wooden: It’s my own conscience that would guide me on things. I make many mistakes of judgment that I have done, but I hope I don’t make mistakes of the heart. I always felt in teaching, one of the most difficult things I had to do was cutting the squad. You have a lot of players come out, they all want to play and you can only take so many, you can’t take them all. That’s hard. Sometimes maybe you have 15 players you keep to work with, but when you travel you can only take 12. You have to leave three at home. That’s hard, particularly the first when you decide who the 12 of the 15 are going to be. Those were difficult things. At the end of the year, when you give awards, some don’t qualify. That’s hard. Those are the things I tried to do that I think was right. I’ve always said that when coaches were complaining about pressure, I don’t buy that at all. I don’t buy that at all. Do you think a salesman doesn’t have pressure? Do you think a barber doesn’t have pressure? He doesn’t cut all the hair in town. The butcher doesn’t sell all the meat in town. A salesman, if you don’t do a good job, they’ll put somebody else in your spot. How about a surgeon performing delicate surgery? Oh my goodness, there’s far more pressure than the coach is going to have. And the only pressure that amounts to a hill of beans is the pressure one puts on one’s self, and you better put pressure on yourself. If you’re not putting pressure on yourself, you’re cheating. You’re cheating yourself, you’re cheating those under whose supervision you are, you’re cheating others. But if you are affected by outside pressures, that’s a weakness. As a coach, if you let the media affect you, if you let the alumni affect you, if you let the parents affect you, they’re going to keep you from doing what you think is proper and right and correct. You should know better than they. This is your profession. You’re working at it every day. You see these players every day. You see them together. You should know more about it. If you let the fact that others don’t think you do bother you, you can’t go and cut meat like the butcher can. You can’t cut hair like the barber can and so on down the line. So don’t worry what others think about. Somehow I was brought up to not let those things bother me, outside pressures. I never worried about a job. I think I can get a job and I think I can get the job I want, but I’ll get a job. I’ll feed the family. That’s the important thing, to take care of my family. I think you can do that. So I never worried about a job and I think that probably because I didn’t let outside pressures unduly affect me. I’m not saying you don’t feel them. You don’t like to be criticized. No one likes to be criticized. I didn’t like to be criticized, but at the same time, you’ve got to accept it and do what you think is right and not let outside criticism sway you. At the same time, don’t be stubborn. You can be wrong, you know. We’re all imperfect.

When you came to UCLA, you wanted to quit after two years. What persuaded you to stay?

John Wooden: I didn’t want to quit. I wanted to leave. Let me put it that way. I had been led to believe by those under whose supervision I was — shown plans for a new building, a place on campus — when my three years was up, that we’d have a nice place to play on campus. Well at the end of two years, nothing had been done and I could see that it’s not forthcoming. The conditions in which we had our practices and played our games in comparison of what I’d had, they didn’t compare with what we had in high school back in Indiana. We were practicing on the third floor of an old gymnasium with gymnasts practicing on one side and Briggs Hunt and his wrestlers down below. I loved the coaches, both of them. We became very close, I think, because we shared adversity and that brings you closer. Sometimes trampolines on the other side of the floor, and sometimes beautiful young co-eds would be up there in leotards jumping on those and you’re trying to get your team’s attention. I wouldn’t notice them, but my players would. After my first two or three years, as you know, we played games in Venice High School and Santa Monica City College, Long Beach City College, Long Beach Auditorium, Pan Pacific, all over. We played home games in as many nine different places.

Purdue came up with a very fine offer — a lot more money and better conditions in every way, and I was tempted. But when I first came, UCLA only wanted to give me a two-year contract and I had insisted on a three-year contract. When Purdue contacted Mr. Ackerman and Mr. Johns, Director of Athletics and Graduate Manager of Athletics about contacting me, they gave permission and told them it was fine. They told me that they had given permission, but they reminded me that I had insisted on a three-year contract and they intended to honor their part and they thought I would, too. I guess they had learned enough about me in the first two years that they probably had me there. So I decided that I would stay. Following that, I always had a one-year contract. The one-year contract always had the option for me to renew for one more year. It was a one year contract, but it was really a two-year in a sense. It was a continuing option every year from that time on. I never had more than a one-year contract with an option for my last 24 years. After three years, we were more settled, more acclimated.

Remember, I came from the farm, the country, and Los Angeles was frightening to me, definitely frightening. I’d say from the beginning, Nellie, my dear wife wasn’t the happiest she could be. Neither were my children at the very beginning, but after three years my children were pretty well settled. They didn’t want to leave their new friends, and we were more acclimated to Los Angeles and always loved UCLA. It was nothing against UCLA. It was just the fact that the facilities with which we had to work with and the conditions under which we played and practiced that way. You may or may not have heard this, but for my first 17 years in that old gym, I with my managers swept and mopped that floor every day before practice. Every day I had the buildings-and-grounds people build me two six foot-wide brooms and six foot-wide mops. And, we’d first sweep it to get the dust off from the activity in there during the day, and then dampen these mops, and I took the easy job, I must say. And I didn’t want managers doing things I wouldn’t do myself, but I’d take the easy job and take a bucket and go along in front of them just like I was feeding the chickens to get it a little damp. I did that for 17 years. A lot of people don’t know that. When these coaches today start complaining about things, I say, ugh! With all the things they have today! When we got Pauley Pavilion, I just felt, gee, this is tremendous, really tremendous, and it was. But, yes, I would have left had I only taken the two-year contract as they wanted me to when I came. But when I did take a three year… I’ve always been against the people who fail to honor contracts. I’d even go farther than that and say word of mouth was good enough. To me, that’s a contract if you make it. Now today, I don’t think even the written contract, many don’t think too much of even that.

You’ve often said that you didn’t want your teams to have peaks or valleys, that you didn’t believe in getting them emotionally charged even for big games.

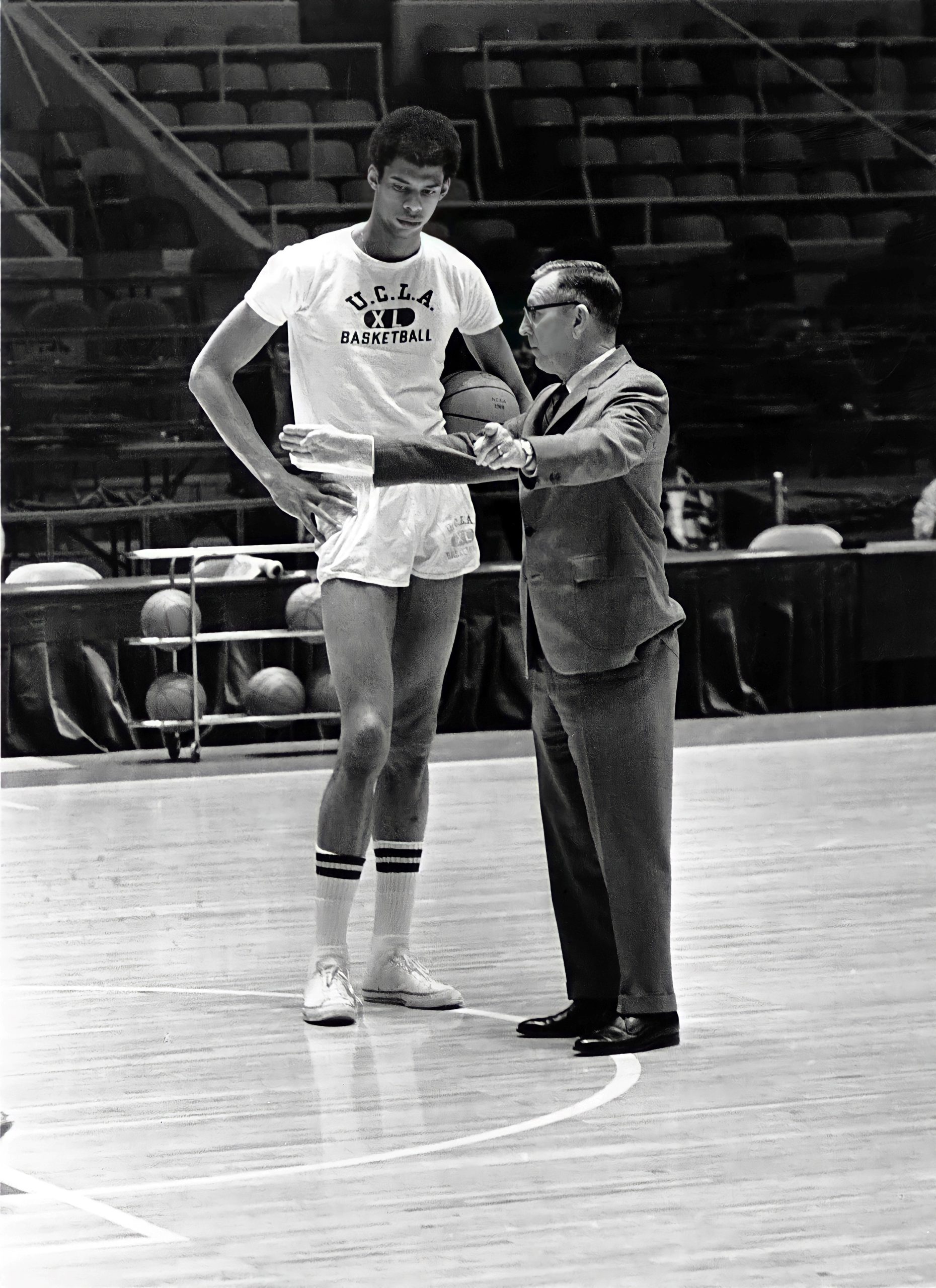

John Wooden: No, I never believed that. Let’s say I were coaching football. If there were certain defensive people that I’d want really charged up, I might try to charge them. But, I don’t think I would ever do that with my touch positions, and basketball is a touch game, for the most part — from an offensive point of view, certainly. I think for every peak there is a valley. if you try to get them emotionally high, I don’t think it’s lasting. It’s like warming up prior to a game. I want my players to understand we’re out there for a purpose. It’s to get loosened up, get warmed up, get accustomed to the background behind the baskets you’re shooting and get loosened up to play. I think for years I was wrong. I’d try to loosen up players all exactly the same. Now, an Alcindor doesn’t need to be loosened up the same way that a Mike Warren does. Yet I was doing that. For a long time, our pre-game meal would be exactly the same for everyone in practically the same amounts. Gracious sakes how wrong I was. I learned finally if this extra wants some pancakes, for him that’s all right. But for another one to have pancakes, oh no, that would be wrong. One kid could have a bowl of chili and a glass of milk, and I’d think that was horrible. Yet I had a player that did that and he never tired. It depends a little bit on your background and what you’re accustomed to. For a long time I didn’t understand that. Apparently, I was a slow learner.

Your players accepted their roles. They had no choice. You insisted on discipline. What is the role of discipline in your success?

John Wooden: I say a coach has the greatest ally in the world if he isn’t afraid to use it, and that’s the bench. Put him on the bench. They all love to play. I hear comments like “Well, he didn’t want to play.” I think they all want to play. I don’t care how good he is if he isn’t producing, it’s just potential, and potential doesn’t produce. It isn’t much good. No better than someone else that doesn’t have that potential. So I think that putting him on the bench, you have that ally.

I tried to explain to my players that every person has a role and every role is important. You may not hardly get in the game, but your role is helping develop these players that are going to play more, and that’s extremely important. And I like to use that with them. Sort of keep this in mind: “I will get ready and then perhaps my chance will come.” Now if you’re not ready and your chance comes, when is it going to come again? It might not come again at all. So always think in terms, I will get ready and then perhaps my chance will come. Fill your role. Is a powerful engine in an automobile any more important than a wheel? What can you do if you lose a wheel? What good’s that engine if you lose a wheel? What good is that wheel if you lose a nut that holds it on? You don’t have it. So you may be just a nut, you may be just a wheel, and you may be a powerful engine. If you’re not all together on the same page, we’re not going to accomplish what we’re capable of accomplishing. I don’t say it’s easy to get them to accept their roles, but you’ve got to — in practices, for example — you’ve got to pay attention to the players that aren’t getting to play very much. The players that are getting to play a lot get praised in the papers. They’ve got the alumni patting them on the back and all that. These others, they’re not getting that. You have to give it in practice. That’s why in some ways, I think I became a little closer with some of my players that didn’t get to play very much than I did with some of my stars. They must know that you care for them. Just because they’re not getting to play that much, you still care for them just as much as the one that’s playing more.

You’ve talked a lot about self control. You were known to have things to say to opposing players and coaches and officials. Did you have to bring yourself under control as a coach?

John Wooden: Oh, of course you have to keep your emotions under control. In my talking to officials, no official or opposing player ever heard me use profanity. They would never hear me call them bad names in that sense. I badgered officials, but maybe it was “Call them the same at both ends,” or “What’s the traveling?” or giving some protection and things of that sort. To opposing players I might say, “Do you ever let so-and-so shoot?” But never would I call them a name or anything of that sort. These other things, the other side was very guilty of. I think, in 40 years of coaching, I had two technicals called on me.

Do you always pay a great deal of attention to detail, to the small things?

John Wooden: I think very definitely it’s the little things that make the big things happen. It’s putting your shoes on properly. It’s getting the wrinkles out of your socks so you won’t get blisters. Those are important things. It’s making sure that no soap is left on the shower room floor where someone — maybe not you, but somebody else — might slip and fall and hurt themselves. Just little things like that. They may seem inconsequential, but I think they’re important. I think teaching your youngsters to be courteous to airline stewardesses, courteous to waitresses, courteous to all people in hotels, I think makes you a better team. I think that helps your basketball. I think that makes you a better basketball player. I think it brings you together more. I think it makes you more considerate of others. Team spirit is just being considerate of others, in my opinion.

I believe those little things helped us, and I also believe in the discipline. But remember, you’re imperfect, and when you see that you’re wrong, don’t be too proud to change. Admit it, and all those working with you are going to do better.

How many coaches today are teaching their players how to put their socks on?

John Wooden: I can’t answer that. I don’t know if any are. But I learned that as a high school coach. You’re more susceptible to blisters. I also noticed that most college players, high school players too, wear shoes that are too large. Basketball is game of quick movement: stop, start, turn, change of direction, change of pace. If there’s that much sliding to the end of the toe, you’re going to get some blisters. So I decided what size shoe you’re going to wear. I want your toe right at the end of the shoe so that when you stop, there’s not going to be any sliding back and forth. I think that’s important. When we have our youngsters, you know, we buy shoes for them. You used to say, “We’ll get them a thumbnail longer.” Kids never get to wear shoes that fit. By the time their foot grows into that shoe, it’s worn out, so you get them new shoes a thumbnail too long. I think that’s the custom of always wearing them a size too large. Almost every player I had, I’d put at least one size smaller than they were accustomed to wearing.

Never criticize your teammate. Never. That’s unpardonable. That’s my job. I’m paid for it. Pitifully poorly, I would tell them, but I’m paid for it. Don’t you do it. And no word of profanity or you’re off the floor for the day. No excuse for that. No excuse for that. Now that, in turn to me, will help them maintain self control. The maintaining of self control is going to make them a better basketball player. It’s more than just the use of profanity, although I don’t want it at all. So I think those are little things that I think help bring big things about.

Do you think there’s such a thing as destiny? I mean, do you think you were destined for achieving the success that you achieved in your chosen profession?

John Wooden: No. I don’t think I was destined at all. I’m a fatalist to some degree. I would say that, but I don’t think It was destined. I don’t know. I went to Purdue to become a civil engineer. That’s why I went there. I did not know at the time that you had to go to summer school every summer to get your degree in civil engineering. I found out at the end of my freshman year that I’m going to have to go to civil camp every summer. I can’t do that. I didn’t get paid and I had to work in the summertime. Was that destiny? Nah. It was just something that high school counseling hadn’t made me aware of. Had I been aware of that, I wouldn’t have gone to Purdue. I’m sure of that. I would have probably gone to Indiana University, which is only 70 miles from my high school, so I could be close to Nellie. I wanted to be a civil engineer, but I couldn’t do it. So don’t complain. Don’t howl. As dad said, “Don’t complain about the things over which you have no control. Make the most of what you have.” So I changed to liberal arts and eventually became an English teacher. I don’t think it’s destiny. I don’t think I was destined to be a teacher, no. It just turned out that way, but I don’t think it was destiny.

What about the role of chance, of luck, in a person’s life? For example, you had an appendectomy in World War II which prevented an assignment that could have cost your life.

John Wooden: That’s right.

There was a snowstorm and Minnesota couldn’t call you and UCLA did.

John Wooden: That’s right.

What about chance? What about luck?

John Wooden: There’s a certain amount of chance in everything, yes. I think there’s such a thing as being in the right place at the right time, but I don’t think that’s destiny. I think it is just chance. Another time, I had to cancel a flight on a plane from Atlanta to Raleigh, North Carolina that crashed and everybody was killed. I had a ticket on that plane and had to cancel it and go the next day. The next day I flew over the crash site in the same type of plane that had crashed the day before. Is that destiny? No, that’s not destiny, but chance perhaps, perhaps luck. There is a certain amount of luck that comes in life itself, in sports and in all professions.

If you could say one thing to America’s young people today, what would you say?

John Wooden: If they would buy it, what would be most helpful is what Dad said, “Don’t compare. Don’t try to be better than someone else. But whatever you’re doing, try to be the best you can be. Take advantage of every day. Make each day your masterpiece.” That would be one of the things that I could say. There are other things that are extremely important. They must have faith. They must believe. They must not complain. Individually, don’t compare, just try to make the most of what you have under the conditions that exist for you and try to improve those conditions. No one can do more than that.

If you were to read one book to your grandchildren, what would that book be?

John Wooden: It would depend on the age of these grandchildren. I have seven grandchildren and nine great grandchildren now. My seven grandchildren are all grown. The Bible is the one, by all means, the most important and the greatest of all. There’s no place in it that you can’t learn something. If everybody would read it and study it a little bit every day. There’s no other book that can compare with that. There are a lot of good books, but, there’s none that would compare with the Good Book.

This is not an easy question, but what does the American Dream mean to you?

John Wooden: I get a lot of requests from parents who are having their first child and would like for me to send them a pyramid and make some inscription on it, maybe some verse from the scriptures. Almost invariably, I will say, “Best wishes, and I hope you’ll grow up into a world where there will be enduring peace between all nations and true brotherly love among all people.” First Corinthians, 13.

You were recognized as a player with great inner drive, great desire. Where do you think that came from?

John Wooden: Probably from my upbringing on the farm and learning that chores must be done first, but there should always be time for play. That was Dad, again. That and seeing us lose the farm, through no fault of my father’s. Seeing these things happen and learning from him to try to do the best you can do and don’t worry about how somebody else does. That carried over in all my teaching. I tried to teach that in English class. Don’t worry about this person’s going to get an A or something. Do the best you can do.

In my coaching, I probably scouted other teams less than any other college coach in the country. Why? I want to concentrate on my own and try to prepare them for each eventuality. Be more concerned about your own team than the other team. I say, “Go get the ball.” I want to get the ball. Now, that doesn’t mean I’m not going to try to get in the path of somebody else. Go get it. That will keep him from getting it.

What is the importance of character to one’s success in life, the idea that you don’t quit?

John Wooden: One of the points in my pyramid is intentness. Now, intentness could be determination. It could be persistence. It could be perseverance. It’s carrying on. I’ve been asked, “Do athletics build character?” And my answer has been consistent. “It can, and it can tear it down. It can do either one. It depends on the leadership.” I believe that to be true. I say that, in athletics, (given) equal ability, the one with the better character will emerge on top. By having better character, you accept things better. You work harder. You don’t worry so much about the other fellow. You do your best. I say, “Let’s have character, not be a character.” I think character gives you more peace. And if you have more peace with yourself, you’re going to function better. In a way, not probably connected exactly with this but some other things, when Socrates was falsely imprisoned, facing imminent and unjust death, he was at ease. There was such tranquility about him that his jailers who were mean, mean, maybe the meanest people of the day. They couldn’t understand. They said, “Why aren’t you preparing for death?” Socrates answer was, simply, “I’ve been preparing for death all my life by the life I’ve led.” If you have character, you’re at peace, at ease with yourself. Therefore, you’re going to have poise and you’re going to function near your particular level of competency.

What is the one bit of advice you wish you had been given when you started your career?

John Wooden: I think I was fortunate and blessed from my very earliest days, by Dad and by Nellie, my high school sweetheart, later my wife of over 53 years. I was associated with people who were of immense help to me. I’m far from perfect, but I was blessed to a degree that many others never had. Take so many of our youngsters today in the inner city, from broken homes; they miss so much. I was lucky. And, I’m glad that things…Well, I don’t know. Dad also developed the idea within me and my brothers that we don’t look back. Look forward. You’re not going to change anything. Learn from the past, but you’re not going to change it. Nothing will change it. The future is yet to be. And, can you effect the future? Yes. How? By what you do every single day. Either consciously or subconsciously Dad, more than anyone else, brought that about.

”I’ve shut the door on yesterday, thrown the key away.

Tomorrow holds no fears for me, for I have found today.”

I always liked that.

Is it possible to describe the emotion you are feeling the night of a championship game when you walk out onto that floor, and it’s all on the line, and you feel you’ve done everything you can do, and here it is?

John Wooden: Cervantes said, “The road is better than the inn.” It’s the road to getting there is the very important part. The end in some ways, it’s exhilarating in some ways, it’s a let-down. It’s the getting there. I think Robert Louis Stevenson said, “It’s better to travel hopefully than to arrive.” Once you arrive, the journey is over in a sense. It’s the journey that’s the important thing. Yes. The fact that it is an accomplishment for which you’ve been working gives you a feeling, maybe the best feeling from a coaching point of view, when you just see the thrill it is giving the youngsters under your supervision. My teams got to the National Championship ten times, the National Championship game, and we happened to win every one of those that we got there. Before the end of each game… none of them were determined in the last seconds. We had them won within the last minute or so. And there would be a time-out. There was in every one. Each time, I told my players, “Now I’m very proud of you. You’ve had a great achievement. But now, when this is over, don’t make a fool out of yourself. Let our alumni do that. Feel good. Cut the nets down if you want to, but don’t get carried away. This is something for us to enjoy for the moment, and let’s not get carried away. But it’s been a great accomplishment and I’m very proud of you.”

Did you ever go into a game feeling you had to win it?

John Wooden: I can’t really say that I can single out any games that gave me the greatest satisfaction. There are a lot that did, and not all of them were National Championship games. People feel that when we lost at Notre Dame after we’d won 88 consecutive games, that must have been a tremendous let-down, and it wasn’t at all. We broke the record. The old record was 60 in a row. We broke the record of 61 at Notre Dame. Had we lost that game that would have broken the record, that would have been a let-down. People say, “How about losing that game in the Astro Dome? For the largest crowd to ever see a game and for the largest televised audience, they say, to ever see a sporting event at that time. That must have been devastating.” And I say, “No. It was a non-conference game.” We had to win the conference to get in the tournament in those years. We were playing with Alcindor definitely, definitely not himself at all. So that was disappointing, just like any other game would be disappointing to lose. Every game you lose is disappointing, but nothing like losing a conference game that would keep you out of getting into the tournament. Now how about the North Carolina State game in ’74? Yes, that was a devastating loss. Part of it because we twice had the lead and we lost it. We had an 11-point lead in the middle of the second half and got tied. We had a seven-point lead in the first overtime and lost. Yes. That’s devastating, because we let it get away from us. I don’t want to take anything away from North Carolina State. They took advantage, and that’s to their credit, but we let it get away.

Do you think there’s anything you could have done differently in that game to have avoided that?

John Wooden: I should have called a time-out before I did. We used the same thing we’d been using for years and it seemed to work pretty well. It didn’t work in that game. How about the loss at Notre Dame? That wasn’t devastating at all, but Notre Dame scored the last twelve points against us. No one ever scored twelve consecutive points against us, and they did, the last twelve points of the game. That’s bad when that happens, but not devastating because it’s a non-conference game. We had already broken the record by 27 games. A lot of our alumni weren’t happy. They wanted 100 in a row, not 80. They weren’t happy with 88. They were extremely happy at 61 when we broke the old record. Then, if we had got 100, they’d want more.

What about the pressures that come to bear on someone in your position: recruiting, the alumni, filling the arena, winning?

John Wooden: Just do the best you can. Don’t worry. I think the pressure — you’d better put pressure on yourself and do a good job. And if you put pressure on yourself to do a good job, you’ll do a good job. Nobody can do more than that. If you’re affected by those alumni and those outside pressures or what not, if you’re worried about your job for any other reason, you have reason to. But I can say honestly, and I’m very sincere about it, the pressure didn’t bother me. The pressure didn’t bother me. It gets to be like Richard Washington, who hit that shot to win the Louisville game. Someone said, “How in the world did you have what you set up to get Washington that shot?” And I said, “He’s the wonder shooter.” I said, “First of all, he’s a pretty good shooter.” I said, “Second, Richard’s loose as a goose. And if he misses? To him, you can’t make them all.” But he didn’t expect to miss, because he’s a good shooter. He expected to make that shot. Now if I had let somebody else shoot that shot, they’d feel they have to make it. If you feel you have to do it, that, I think, hurts your chances of doing it. It’s kind of like character and reputation. Your character is what you are, and you’re the only one that truly knows that. Your reputation is what others perceive it to be, and they can be wrong. So which is the most important? What you really are. It doesn’t make any difference what others might think. You’d like for them to think well of you, but it really doesn’t make any difference. You’d just like for them to. But boy, it’s very important what you think about yourself. That’s very important. That’s probably the most important thing there is.

Thank you for speaking with us today. It’s been a privilege.