The Constitution doesn't belong to a bunch of judges and lawyers. It belongs to you.

Anthony McLeod Kennedy was born and raised in Sacramento, California. His father, Anthony J. Kennedy, a former dock worker from San Francisco, had worked his way through law school and built a substantial practice as a lawyer and lobbyist in the state capital. Young Anthony Kennedy enjoyed following his father on his business rounds and developed an early taste for the world of government and public service. After school hours, he served as a page boy for the California State Senate.

Anthony Kennedy graduated from Stanford University, spending his senior year at the London School of Economics. After graduating cum laude from Harvard Law School in 1961, he served for a year with the California Army National Guard. He accepted a job with a law firm in San Francisco, but when his father died unexpectedly in 1963, Kennedy returned to Sacramento to take charge of his father’s firm. In addition to his law practice, Kennedy pursued a lifelong interest in legal education. From 1965 until his appointment to the Supreme Court more than 20 years later, he was a Professor of Constitutional Law at the McGeorge School of Law, University of the Pacific.

As a prominent attorney in Sacramento, Kennedy attracted the attention of then-Governor Ronald Reagan. When a seat on the United States Court of Appeals fell vacant, Governor Reagan recommended Kennedy to President Gerald Ford. President Ford appointed Kennedy to the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in 1975. At age 38, Kennedy was the youngest federal appeals judge in the country. His record on the federal bench was generally a conservative one, but Kennedy approached each case on an individual basis, and showed more interest in adhering to the letter of the law than in proclaiming an all-embracing theory of jurisprudence. As a federal judge, he also participated in the Judicial Conference of the United States, serving on the Advisory Committee on Codes of Conduct, from 1979 to 1987, and chairing the Committee on Pacific Territories from 1982 to 1990. In 1987 and 1988, he also served on the board of the Federal Judicial Center.

In 1987, Associate Justice Lewis Powell retired from the United States Supreme Court. President Reagan first nominated Robert Bork to replace Powell, but the nomination was rejected by the Senate after an unusually contentious debate. President Reagan’s second nominee for the Supreme Court seat, Douglas Ginsburg, withdrew his name from consideration when a controversy erupted over his admission of past marijuana use. In 1988, entering the last year of his presidency, President Reagan was determined to name a candidate who would be assured of confirmation, and turned to his old Sacramento acquaintance Anthony Kennedy, who was perceived as more pragmatic and less driven by ideology than the two failed nominees. Kennedy received the highest possible recommendation from the American Bar Association, and the United States Senate confirmed his appointment by a unanimous vote. Kennedy took his seat as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court on February 18, 1988.

After joining the Supreme Court, Justice Kennedy often sided with the Chief Justice, the late William Rehnquist. He has generally shared Rehnquist’s conservativism on criminal law issues, voting to uphold the constitutionality of workplace drug-testing for railroad workers after accidents, and for employees of the U.S. Customs Service. On other issues, he has favored the right to personal privacy over the state’s police power. Kennedy wrote the Court’s opinion invalidating a provision in the Colorado Constitution denying homosexuals the right to bring local discrimination claims.

In 2003, he wrote the majority opinion in Lawrence v. Texas, invalidating the criminal prohibitions against homosexual activity between consenting adults. He joined Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and David Souter in a plurality opinion in the case of Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), which re-affirmed the Roe v. Wade decision recognizing the right to abortion while permitting some state restrictions. On the other hand, Kennedy joined with Court majorities in several decisions favoring states’ rights and capital punishment and invalidating federal and state affirmative action programs.

In addition to the awesome responsibility of sitting on the nation’s highest court, Justice Kennedy has carried on a remarkable series of educational activities. He has lectured in law schools and universities throughout the United States and in other parts of the world, particularly China, where he is a frequent visitor. Following the 2003 defeat of Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq, Justice Kennedy designed a three-day educational program for the country’s senior judges. An educational exercise he called “Dialogue on Freedom” has been used by over a million high school students throughout the United States. He has also written an exercise for attorneys and law students entitled “The Trial of Hamlet,” in which forensic psychiatrists testify regarding the criminal responsibility of Shakespeare’s hero.

In 2013, the Supreme Court considered two historic cases concerning same-sex marriage. One case, U.S. v. Windsor, turned on the federal “Defense of Marriage Act” (DOMA), which denied federal recognition to same-sex marriages performed under state law. The second case concerned California’s Proposition 8, a referendum question, approved by the state’s voters in 2008, which amended the California Constitution specifically to bar local jurisdictions from performing same-sex marriages. After two lower courts found this measure unconstitutional, the Governor and Attorney General of California accepted the lower courts’ decisions and declined to press the matter further. The proponents of the original measure pursued the matter to the federal Court of Appeals and to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In a five-to-four decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the proponents of Proposition 8 lacked legal standing to pursue the matter in federal court because they had suffered no “concrete and personalized injury.” Justice Kennedy dissented from this opinion, writing for the minority that the Court did not “take into account the fundamental principles or the practical dynamics of the initiative system…” Both the majority and minority opinions addressed only the plaintiff’s standing, not the constitutionality of the California statute.

In the DOMA case, the Court did address a constitutional issue, again in a five-to-four decision, but in this case Justice Kennedy led the majority. “The federal statute is invalid, for no legitimate purpose overcomes the purpose and effect to disparage and to injure those whom the State (of New York), by its marriage laws, sought to protect in personhood and dignity,” he wrote, speaking for the majority. “By seeking to displace this protection and treating those persons as living in marriages less respected than others, the federal statute is in violation of the Fifth Amendment.”

In June 2015, the Court took further action, once again dividing five to four, and asserted the right of gay couples to marry throughout the United States. Writing for the majority in Obergefell v. Hodges, Justice Kennedy wrote, “The Court now holds that same-sex couples may exercise the fundamental right to marry. No longer may this liberty be denied to them.”

Justice Kennedy’s ability to come to his own conclusions in these related — but very different — cases, based on his understanding of the law, without bias or partisanship, is characteristic of his honest and dedicated service to the Court and to his country. In the summer of 2018, Justice Kennedy announced his decision to retire from the Court after 30 years of distinguished service.

“Our system presumes that there are certain principles that are more important than the temper of the times.”

In today’s politically charged debate over the role of the courts in American society, Justice Anthony Kennedy has long stood as a model of judicial temperance and objectivity. At 38, Kennedy was the youngest federal appeals judge in the country. Appointed to the Supreme Court by President Reagan in 1988, Kennedy won the unanimous approval of the United States Senate.

As a Justice of the Supreme Court, he resolutely evaluated every case on its merits, without attempting to promote an overriding political viewpoint or philosophy. Even those who disagreed with his findings were compelled to admire his carefully drafted opinions. Although he generally voted with his conservative colleagues on crime issues, he at times sided with the Court’s more liberal members on issues of free speech and privacy.

His warm, unpretentious demeanor enabled him to negotiate compromises between his fellow Justices and rise above the political passions of the moment. His longtime commitment to international legal education has insured that his influence will extend far beyond his 30-year tenure on the nation’s highest court.

Did you always know you wanted to be an attorney?

Anthony Kennedy: Oh, there was really, really no choice. My dad was an attorney. I think he knew he would not have a long life. He was a solo practitioner. He would take me to his trials in Northern California, in these little towns because he was lonely. I’d say, “Oh, I have a geometry test.” He said, “I’ll teach you whatever you need to know.” So, I probably saw ten trials before I was out of high school and took notes at the counsel table, and worked late in his office typing documents. So, it was not a question, “Would you be a doctor or a lawyer or a priest?” It was just assumed.

You were always a lawyer in training?

Anthony Kennedy: I suppose. I really wanted to be a doctor.

You were not yet 40 years old when you were appointed to the federal bench. You were the youngest federal appellate court judge in America and the third youngest in the history of this country. How do you account for that?

Anthony Kennedy: In a way, I was a little ahead of the curve because of my experience with my father and being basically a law clerk in his chambers. So, I was a little ahead of the curve in that respect. I think it’s a mistake to go on the appellate bench too young, and I might have been too young, because it’s very important that you bring to each case a new energy, a new commitment, because what you do is very important to the litigants, and so I was very careful to watch myself for the signs of burnout or disinterest. And so, I’ve always taught, and I continue to teach, which I thought was important to do. But, as I said, I wanted to be a trial judge. Watergate had come along; they weren’t making new trial judges, and there was an opening in the Court of Appeals. And then Governor Reagan asked if I would like to be considered for that, and I thought, “Well, you know, the merry-go-round goes around, and there’s an empty horse, and if you don’t get on it, the next time it goes around somebody is on the horse.” So, I thought maybe I should take this opportunity.

Was there a learning curve for you?

Anthony Kennedy: There’s always a learning curve in any occupation, in any new project you undertake, so of course there was. It was a more introspective occupation than I had thought. You have to ask yourself, “What is it that’s making me do this? Why am I deciding this?” It’s surprising how often you have to go back to square one.

You know, all of us have an instinctive judgment that we make. You meet a person, you say, “I trust this person. I don’t trust this person. I find her interesting. I don’t find him interesting.” Whatever. You make these quick judgments. That’s the way you get through life. And, judges do the same thing. And, I suppose there’s nothing wrong with that if it’s just a beginning point. But, after you make a judgment, you then must formulate the reason for your judgment into a verbal phrase, into a verbal formula. And then, you have to see if that makes sense, if it’s logical, if it’s fair, if it accords with the law, if it accords with the Constitution, if it accords with your own sense of ethics and morality. And, if at any point along this process you think you’re wrong, you have to go back and do it all over again. And that’s, I think, not unique to the law, in that any prudent person behaves that way.

Some law professors say, “We teach you how to think,” as if nobody else does. That sounds a little bit pretentious. All good teachers — all good citizens — are interested in thinking. It is true that in the law we teach you to think about very ordinary things in a very formal way, and I had to realize that. The other thing I had to learn was this:

Lawyers, judges, law professors talk all the time about stare decisis. If you want to say something important, we use Latin because it makes it sound more important. Stare decisis means that you’re bound by what previous judges have decided, unless it’s very wrong and very important, and then you have to depart from that precedent, and that’s a major event in the law. But essentially, you’re bound by stare decisis. When I went on the Court, I thought, “Well, this is not very interesting. It’s antiquarian. It’s like historical research.” I thought I’d be like a scientist putting together an explanation for an experiment that had failed, and I go back and say, “Well, you did this wrong or you did that,” and I was interested in it because I love the law, but I thought it was rather limiting. I was quite mistaken. Really, the dynamic of being bound by precedent, the so-called stare decisis, is very forward-looking, because it teaches you that you will be bound by what you do. You’re the first person that will be bound by what you do, and if you’re on a court which reviews other courts, they will all be bound by what you do. So, there is really a very forward-looking dynamic to judging. You must ask yourself, to the extent that you can without being imprecise, “How will my judgment play out in the future?” And, there’s a lot of looking out the window in that job.

I was in Thailand right after the tsunami. A judge’s conference had been scheduled, and I thought, “Gee, should we be having a judge’s conference in the wake of this terrible human tragedy?” Colin Powell was still the Secretary of State. The State Department called and said, “This is very important. You have to go to Thailand for this judge’s conference. They’re talking about what it is to build a society, and you build a society with a legal system. Law is part of the capital infrastructure.” We can talk about that later, but going back to Thailand…

We went to Bangkok, I think it was three and a half weeks after the tsunami. It was 400 miles from where the tragedy had occurred, and the Buddhist people are very quiet and introspective themselves, and didn’t want to talk much about the specific tragedy. But, I talked there with a priest who had been working with the victims of the tsunami. And he used the method pioneered by the psychologist Robert Coles, who would talk to little children, and he’d give them a blank sheet of paper and some crayons and ask the child to draw while they were talking. As if, in this interview, you were asking me to draw something, and he would — he worked with 10- and 12-year-old, 13-year-old kids who had lost everything — their brothers, their sisters, their parents, their homes — and he gave that kid four pieces of paper, and at first he said, “Draw what your life was — your parents, your brothers, your sisters, your house. And the second one was, “Draw the tsunami, because you have to confront evil and the forces of nature which have injured you and somehow come to grips with it. You can’t repress this, so draw the tsunami, draw the event.” And the fourth paper, of course, was “Draw what you’d like your life to be.” But the third paper was the hardest, and that’s “Draw the present. Draw the present.” These kids had a particularly difficult problem in drawing the present, because it was a completely changed environment they had to adjust to. But, it occurred to me that maybe it’s the hardest for all of us to draw the present. We’d probably make a mistake when we predict the future, but at least we’re confident that we know what it ought to be like, what we want it to be like. And, judges have to understand that they have to, in part, deal with the present.

I can look back and know what the law was. I can look forward and say at least what I think it ought to be, but you must be careful you’re not missing something. History is moving very quickly, and we’re moving with it, and it’s hard for us to assess whether or not we’re taking the right direction. I don’t think our society as a whole does a very good job, frankly, of asking where they’re headed.

No matter what the field is, you can’t please all of the people all of the time, least of all on the Supreme Court. How do you deal with criticism, with controversy?

Anthony Kennedy: I haven’t thought much about that question. In part, we’re so busy working on the next case, we can’t worry about the last one. You must be very confident that you’re not deciding one way or the other because of popular opinion.

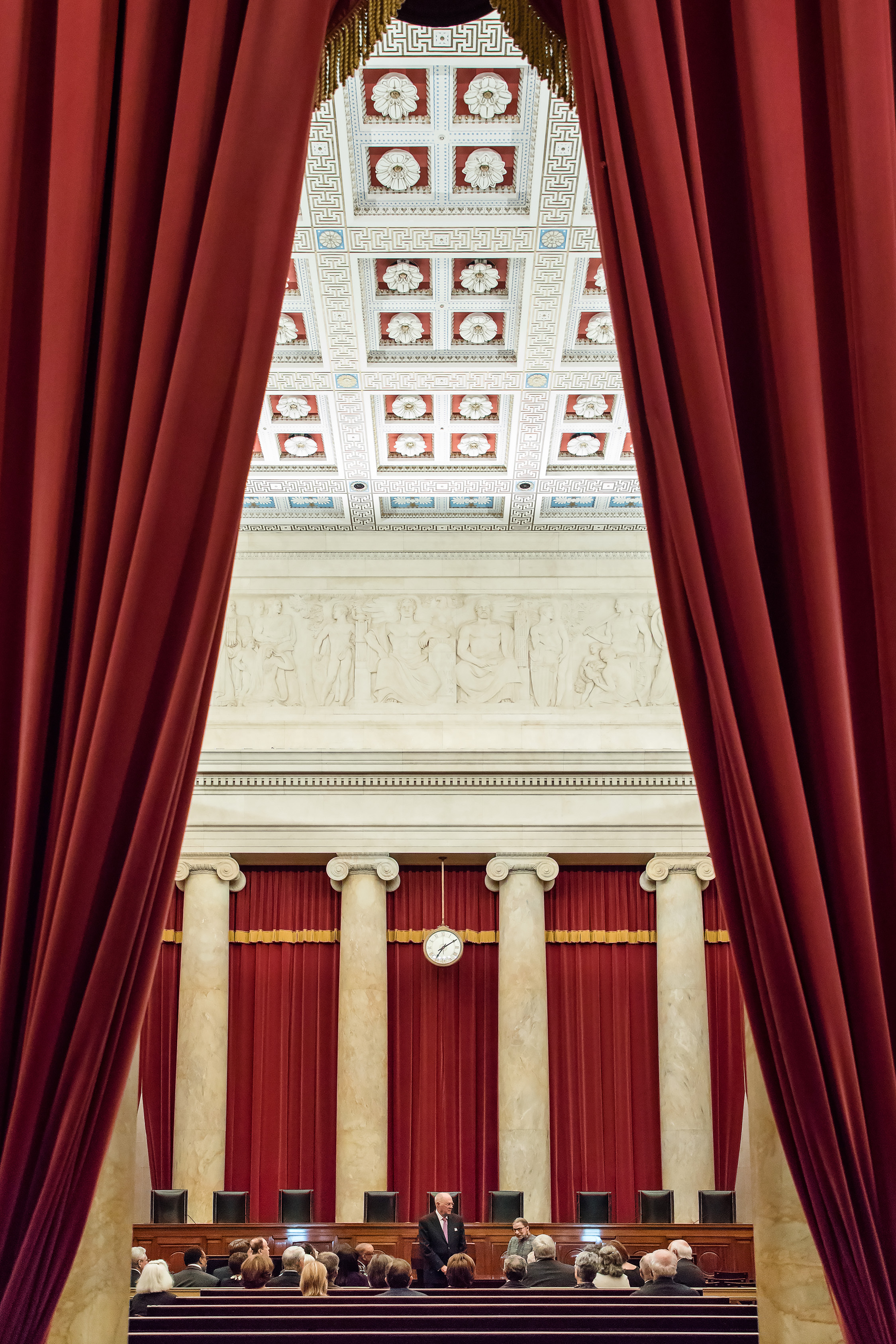

The dynamic of the law is that it transcends — or attempts to transcend — the emotions of the time. That’s the dynamic of the legal system. Most law professors and many commentators say that the judicial review — the idea that courts can set aside legislation — is anti-majoritarian, or contra-majoritarian, so that a majority can’t make its will binding on an injured minority. That’s true in one sense, false in another. It may be true that when we set aside a particular congressional enactment or a state law — which is an awful function, awful in the sense of powerful — it’s true that we, for the moment, may displease the majority. But, if you look over time, if you ask what the American people — the majority of the American people — want over time, over our history, they want judicial review. They want to make sure that the promises of the Constitution are honored, that the commitments we made basically over time with our ancestors are followed.

And, the Constitution defines the American people. Americans have their self-definition — their self-identity — shaped by the Constitution. When we rebelled against England, the rest of the world said, “What do these Americans want? What’s the problem?” The Americans said, “We want freedom.” People in England and Europe said, “Freedom? Those are the freest people in the world! They have all the property they need, all the land. What are they talking about, freedom?” So we had to send a fax back to them, an e-mail, as to what our principles were, what the reason for this revolt was, what the reason was that we were committing our young people to confront the British military. The reason we gave was a legal one. The Declaration of Independence is basically an indictment of King George, and the Constitution is a formulation of what we think the principles of freedom are, and that’s what defines America.

We’re so fortunate. Either by accident or history or providence or design, I think all those. The self-definition, the self-image of an American relates to his or her Constitution. No other country in the world has that. We can’t be smug about this and say no other country in the world can have a constitution, but this accounts for the fact that our Constitution is the oldest constitution in the world. I’ve had the heads of foreign governments ask me, “I think I should amend the constitution to do this and that,” usually something that helps them over the short term. And I say, “You know, a constitution, by definition, is something that has to last over time.” Madison said, “The Constitution must acquire the reverence of its people, and it can only acquire that reverence over time.” And so, the Court wants to — is a way, is one way of reminding Americans, of reminding ourselves that the Constitution must transcend the emotions and the opinions of a particular day. And so, criticism doesn’t bother me. I think criticism is very important. The Constitution doesn’t belong to a bunch of judges and lawyers. It belongs to you. It’s yours. Now, we have to interpret it in this formal way, but you have to live it.

So if there’s a decision people don’t like, of course, we’re pressured about it. I think it’s unfortunate that sometimes people ascribe improper motives to judges. They don’t understand the tradition. A lot of editorial writers just read the dissent, they don’t read the majority opinion. The press does a fair job of reporting what we do, not a particularly good job of reporting why we do it. But that’s because of the time line. They have to meet the 24-hour or 48-hour deadline, and then the public loses interest. Our function is more philosophical and has a broader time line than that.

You have a reputation as someone who can build bridges, who can build majorities, who can achieve compromise. How important is compromise in this system of ours?

Anthony Kennedy: It’s essential.

Sometimes people think compromise means squishy, centrist. It doesn’t. The whole idea of a democratic society is that there must be a consensus, and it’s a consensus that should be based on rational dialogue. I’m not sure that mass politics with modern communications has yet found a way to have a quiet, rational dialogue. I’m not quite sure we’ve found the key to that. But, we not only have to do that in our own society, we must not become a hostile, factious, divisive society. We must be a society that has a broad consensus on certain very fundamental values, and we must do that because after we build bridges of understanding with ourselves, we have to build bridges of understanding with the rest of the world. I was talking to some students around the turn of the century. I guess it would be 1999, I think, and some student raised his hand and said, “What are the great issues of the next millennium?” Or the next 100 years. It was something I should have had an answer for, after dinner table conversation or something, in reflection, but I didn’t. It caught me by surprise. So, I came up with an answer. I said, “We have the great challenge and the first duty to build bridges of understanding with the world of Islam.” And I got more letters from that comment — it was on C-Span — than anything I’ve ever said. Thousands of letters saying, “Why?” People saying — and it struck me that there’s a void there. We’re in a struggle in which our security will depend on ideas. The idea of freedom, if accepted by most of the rest of the world, is our best security. And, we must build bridges of understanding to explain the principles of freedom. And, I’m not sure that we’re doing a very good job at the moment.

Are some decisions harder to make than others? What are the most difficult decisions to make?

Anthony Kennedy: I’ll tell you first the easiest.

The easiest are the technical ones, the things I was trained to do in law school: how to read a statute, how to apply the rules of evidence. I have a lot of help in the history of the law for that. The most difficult ones are defining the components of human liberty, because if you insist that the individual has a particular right, that means the legislature cannot infringe on that right. And, sometimes your own values and your own morals really would disapprove of the conduct that you’re ratifying, but you do so because there’s an area of morality. But, morality really should have an underpinning of rational choice, and each citizen must make a rational choice to determine what is good and what is evil, and those are hard.