You’ve gotten into controversy with the Japanese over the Genome Project.

James Watson: They have the money to do it, and everyone will benefit when it’s done, so why not help get the job done, in sort of a selfless fashion? They find it very hard to change course. They’re actually getting into it, but I make a great distinction between individual Japanese scientists — I have great respect for them — and cultural traditions. Some cultural traditions in our country are terrible, and some in Japan are terrible. I don’t know why we have to be polite about the Japanese, they’re not very polite about us. They go around bowing and giving presents, but that’s just their culture, that doesn’t mean they like us.

What finally brought it to the point where you said you wouldn’t share the results with them, unless they contributed more?

James Watson: I think that’s reality. We have two very different cultures. We’re all products of the Judeo-Christian thing, where we help the underdog. You go to the Far East, they don’t know that concept at all in China. They don’t know what charity is. You help your family, that’s it. You know, we wanted to make the heathens Christian, they don’t care about the heathens. I think there’s a real distinction culturally. I don’t think we should be taken advantage of because we have this Judeo-Christian heritage.

What is your concern about the right to genetic privacy?

James Watson: Our concern is that, if people knew you were predisposed to die of Alzheimer’s disease at an early age, no one would want to give you a job, or they wouldn’t want to give you insurance. So you should also have the privacy of not knowing about your future if you don’t want to know it. I think we should know the future only if you can do something about it. I’m not particularly anxious to know the future if I can’t intervene. Through the Genome Project, I think we will be finding ways of intervening, which will make human life better. And the quality of life will be improved. But we’ve got to be careful as we go along.

Because there are threats to the individual?

James Watson: I think genetic knowledge has predictive power, and sometimes it’s statistical. “You have an increased probability of coming down with cancer.” In the case of cystic fibrosis, if you have the gene, and you’ve got both copies bad, you’re going to have the disease. You’ll essentially know it soon after you’re born. This knowledge, particularly the predictive part of it, should be tightly controlled and probably should only be obtained when you can do something with the knowledge. It shouldn’t just be obtained because you want to see the future; it should be obtained because you want to make the future better.

If an insurance company takes some of your blood to look at your cholesterol, also wanting to scan your genes to see if you’re predisposed to any of 20 different genes, if you found any of them that looked like a predisposition, they could say, “I don’t have to give you insurance. The law doesn’t say I have to insure you. I’ll find someone that looks healthier.” There have been a few isolated cases of this already, but not enough to affect many people. But as the knowledge becomes more prevalent and the costs of the tests go down… We want the tests to go down because we don’t want to drastically increase the cost of medical care, but you’ve got to be careful that the use of this knowledge is really thought through. It’s got to be thought through not just in one summit occasion, but you’re probably going to have to think through almost every different case, for the different consequences for the people. Sometimes we’ll want to limit it, and in other cases it doesn’t make any difference.

Deep down, we’ve got to have the principle that, as an individual, I control whether someone else looks at my DNA. It shouldn’t be someone else’s choice. There are complexities to it. For instance, you could get yourself tested and discover that you were at risk for a disease, and so you could go out and take out a large life insurance policy. That will protect your family. If you knew this, and your insurance company didn’t, then that’s penalizing the other people who get insurance, because the rates will have to go up. How you’re going to handle all these cases is going to be complicated. We’ll spend, this year, about five percent of the money of the Human Genome Program on what we call an ELSI program: ethical and legal and social issues that are coming from this knowledge. I think the amount we spend will increase because, as we get more knowledge, these ethical consequences are going to be greater. We’ve got to think of the people who may be damaged by this knowledge, not think of who might be benefited, but those who might be damaged, and really work to see that we don’t create a paranoia among some people, that their innermost secrets are going to be revealed — things other people would know that you don’t even know about yourself. It’s beginning to be very creepy, and we’ve got to prevent genetics from acquiring this creepy feeling.

Sort of a Big Brother feeling?

James Watson: Big Brother, yes. We’ve got to be very open. Probably the wisest thing I’ve done over the past decade is, when I took the job in Washington, I suddenly had to have a press conference and without thinking I said, “We’re going to spend three percent of our money on ethics.” Probably the wisest thing I’ve done over the past decade. I knew that was important, but I stated it without being forced to do it by someone else. You know, you’re only concerned with science and don’t care about the poor people who might become part of a genetic underclass. I’ve gone out of my way to emphasize that we’ve really got to worry that the genetic underclass exists. We don’t create it, in the sense that some people are going to have the bad luck of inheriting genes like ones which will give you muscular dystrophy, just terrible things. We’ve got to somehow work to ameliorate the consequences. We’ll never be able to do away with all of the consequences of some bad genes, but we’re going to work to minimize the effect. The real aim of our project, much of it, is to try and fight genetic diseases. In fighting them, we can’t be perceived as making the life of those who suffer from them even worse.

If you knew you were predisposed to a certain disease, you might be able to alter your behavior.

James Watson: You certainly won’t smoke. I think that’s quite simple, but you don’t want to create paranoia, where everyone knows that I’m predisposed, or he or she is predisposed, to 20 things, so you end up by doing nothing in your life. You can’t get to that point of paralysis. As we acquire this knowledge, human beings really have to become better educated in what we call human biology genetics. Probably early in life, we’ve got to teach people about genes, and what they mean to human life, and what sort of facts you really know and what you don’t know.

What are some of the practical applications of DNA?

James Watson: The ones we’ve mentioned all really improve the quality of human life. You’re not going to be declared the father of a child if you’re not the father. On the other hand, if you say you aren’t the father and you are, you’re going to be caught. If you’re a rapist, the identity will be firmly established. These are good. There is also a danger. It could also reveal fingerprints that you’d been adopted, and you might not know you were adopted, and learning this would have a terrible effect on you. I think we’ve got to be very careful with these databases of fingerprints, that they’re taken only when necessary. These fingerprints can eventually be reduced to a simple bar code, so it could be on your passport. I think this would be going too far. You could discover things about your parents, or who your parents really are, that there’s no need to know and you shouldn’t. There’s going to be a real privacy case there about fingerprints. The legal people who are arguing about it see only the good things. I wouldn’t want children in high school just doing a genetic fingerprint of their family as a project. Those are the sort of things that I suspect. It’s going to be done, and then you’re going to see that it shouldn’t be done. Finally, we’ll probably get laws registered. Who can do it for a real reason? If there’s no need to do it, why do it?

There has been a lot of discussion on the patenting of the human genes.

James Watson: I think it’s somewhat like that. I think their intention in doing it was correct. They just wanted to be sure that someone else didn’t patent it. But the concept is almost that someone else could own you. They found the gene mutation for cystic fibrosis at the University of Michigan. They applied for a patent, and I think they will license this patent so that many people can make medical tests of it. And that’s fine. But I think they would have been distressed if someone else had had a patent that could have blocked them, because just randomly they were doing it. I think without a function it will create a lot of chaos, as well as make it look like the reason we’re working on the Human Genome is greed. “You’re just trying to work out the sequence so you can own it.” I think you want to work out the sequence to find out more about ourselves.

In the next 20 years do you see our economy and the emphasis on knowledge moving in the direction of biotechnology?

James Watson: Very clearly. If you look at agriculture, the techniques of genetic manipulation are going to vastly speed up the sort of conventional plant breeding processes, or in the case of animal breeding. I think agriculture is going to be dominated by this new technology. I remember the old DuPont slogan we used to hear, “Better living through chemistry.” They don’t say it anymore, because the public perception is that all these chemicals are polluting the atmosphere. Of course, people have the same fear now about biotechnology, that we will change the ecology of the earth. We were in an era where much of human life was dominated by what the chemists did, starting with the dye chemists about a hundred years ago. We’re going to have an era where, essentially, manipulating genes and producing products is going to be a dominant industrial thing. I think it’s almost impossible not to believe this. I mean, there’s so many things that you can do.

Now we’re beginning to see the practical application of these various things.

James Watson: Yes. Look at the Mississippi Delta. Hopefully, the cotton plants which will be grown will be very different than the ones which had been subjected to so many sprayings from pesticides. We may actually be able to control insects better. There are people who say you’ll never quite win, but you always have to try and make improvements. I think the utilization of gene technology may very well be the dominant feature of industry over the next century. There’s no doubt we can do these things. I think we just have to ask who’s going to do it.

Going back to the beginning, if you will, when did you first get interested in science?

James Watson: I became interested in birds at a young age. My father had been an amateur bird watcher most of his life. I think I got my first book on birds when I was about eight years old. I used to go most Sundays with my father to see what birds were around, except in the peak of the summer, or when it was colder, in the winter in Chicago.

I think at sort of a young age I began looking at sort of ornithographical magazines, so I became aware of…of science through people interested in birds, and particularly bird behavior. Because the migration of birds was the thing with which you were dominated. Some birds came through in the spring, and in the fall, and in the winter you saw another collection of ducks. So, how birds could migrate always seemed to be not only mysterious, but almost a miracle as to how they did it. Even today, we don’t know for sure.

Was there a time when you wanted to do something else with your life other than science?

James Watson: No. I always thought that I would be in some intellectual activity. In part because our home was dominated by books. My father was in business. He wasn’t very successful. I think everyone realized it would have been much better if he’d been a school teacher, instead of trying to work in business, to which he wasn’t, I guess, very sympathetic. That was during the Depression, and I think many people were wondering whether capitalism as it was then practiced in the United States had a real future. There were so many people out of work that you wondered whether the system really was fair. So business people were not examples. I would never have thought that I would go into business, because they seemed to be people without any compassion.

What books did you read when you were young that inspired you?

James Watson: When I was young, the chief book I remember was The World Telegraph Almanac of Facts. I just went through and learned facts. Our house was filled with books which we call classics. I read them. All the Russian literature in translation, Dostoyevsky, Turgenev, Tolstoy, and English literature. Nineteenth century literature, some early 20th century. As a boy, when I was going to the University of Chicago, the novels of James Farrell, and John Dos Passos, which tried show what America was like. More or less the way Dickens had tried to convey in England, which often were dominated by economics. Those were the days when you questioned whether capitalism was the moral way to live.

Have things changed, in your view?

James Watson: Yeah. I don’t believe that people are born good. We’ve seen what happened in Communist societies. I don’t think that’s the answer. On the other hand, we still need a safety net for the less fortunate. The elderly used to be the great problem in the United States when I was a child. Then came Social Security. Now you feel sorry for people as they grow old, because they’re growing old, but not because of their economic impoverishment. Often, you have the feeling they’re not as bad off as a family who’s trying to make it with two kids, in a place where they need two cars, and the wife has to work. The struggle has moved to a different group of people.

Were you sensitized to these things by the literature that was in your house as a young man?

James Watson: Yes. I read the New Republic as an adolescent, and The Nation, as well as Time and more center type things. My mother was very Democratic, worked for the Kelly-Nash machine. So we knew the Irish-dominated politics in the city of Chicago, in those days. They were Democrats.

Did the lack of success in the economic realm make books more attractive to you?

James Watson: I guess I was dominated by two things. One was the Depression, and second, Hitler and the coming of the war and the need to win the war. Those were the dominant things. We certainly were never very materially conscious, in the sense that my father had a car, but that had been lost during the Depression. We weren’t really envious of people who belonged to country club, or so on. You know, they were just Republicans.

The idea of keeping up with the Joneses wasn’t important?

James Watson: No, I think the impulse was more to understand why things happened. It was sort of more curiosity about what the world was.

When did you first start to get interested in broader scientific areas?

James Watson: I had science courses in the first two years of high school, so would be exposed to things like the Periodic Table, and at some stage, of course, I became conscious of evolution. That is, probably in a real sense it wasn’t until I went to the University of Chicago. But there they had an unusual program, they took some people after two years of high school. So I would go to the university by street car every day, starting at the age of 15. That was a very great university, particularly for science. And so I knew I was in an environment of great scientists. So it was, I guess, the inspiration I might become one myself.

Was there an event that inspired you most as a young person?

James Watson: No, I think it was just a way of life. My father had a brother who was a physicist on the faculty at Yale, so in a sense I had met a scientist. My father had no real interest in science, per se. He was interested in ethics, philosophy. He liked to find rare birds, but that was sort of a chance, not a scientific interest.

You’ve become interested in chance.

James Watson: You like to do things at the limit of your capacity. I try to promote science at the limit of what you might get done. Doing well what someone else has done before, I’ll never be able to do it as well as they do it anyway. You get more self respect by trying to do something that someone else hasn’t done.

Was there one person who inspired you the most?

James Watson: In those days we were dominated by the radio, and hearing the voice of Franklin Roosevelt, who was probably the dominant figure in American life. He was hated by some of my father’s relatives, I remember. I used to argue with them even as a small boy, because they were so blatantly bigoted. Roosevelt was the enemy. They didn’t really have any money themselves it always sort of amazed me that they could just hate Roosevelt. For my family, Roosevelt was the hope. Then later, when the war came on, Churchill became a very dominant figure. Also, the President of the University of Chicago, Robert Hutchins. He had an extraordinary presence. He looked and acted like a great man, and he was.

What was it about Dr. Hutchins?

James Watson: He was an extraordinary orator. Also, he seemed to believe in the truth, that you should strive for the best in this world, the best in ideas, and an emphasis on thinking, using your brain, reality as distinct from illusion.

You said that one has to have the time to think.

James Watson: I think so. I’m very uncreative now, because someone wants me to do something all the time. I receive letters I don’t have the time to answer, so I’m in a pretty uncreative mood.

Were you a gifted child?

James Watson: I think my teachers thought I was gifted, I didn’t. I think they measured intelligence so much in those days — whether you were mathematical, or a musical prodigy — and I wasn’t. I didn’t handle numbers particularly fast. I could learn it, but by the standard then of, you know, was someone clever, I didn’t think I was clever. I think I was probably good, because I never thought life would be easy for me. I never thought I was better than other people. So I think I certainly wasn’t over-confident.

Did you think life would be hard for you?

James Watson: It was always hard for everyone. Even today. There’s so much uncertainty. So many things really beyond your control. As you grow up, you can’t be sure that a girl will return your love. You just can’t predict that things will turn out the way you want them.

Does science offer more satisfaction, that you can find what appears to be the truth?

James Watson: There’s a distinction between doing it and learning it. When you do it, you don’t know the answers, you may not get the answers. So of course, in being a good scientist you try and choose problems where you have a chance at getting the answer.

You can focus in on the area where the answer may lie.

James Watson: People keep saying, you know, that you have some special way of perceiving the future. But I think really you have a good command of the facts. I think to do science you have to know the past pretty well. And sort of know the facts that you might have to know to get where you want to go. So sometimes you can just come to the conclusion, you just don’t stand a chance, and stay away from it. So you don’t even jump into something that seems just an impossible obstacle. Of course, you’ve got to get one where you have two or three obstacle, and maybe you can jump over all of them, but not too many. And so with time I realized that I’ve never wanted to do anything if I didn’t think I had about a 30 percent chance of getting it done in a year. I’m not a one percent person. You know, I’m not going to Las Vegas trying to get a jackpot. I want to go where, if you’ve got to sort of out-guess other people who think really, you know, it’s impossibly hard to — you know, it’s not impossibly hard, so you jump in. But I don’t jump in something just because it’s there. I jump in because I think there’s a reasonable chance ordinary intelligence will get you through to the answer.

You’re also very competitive, you like the chase.

James Watson: I guess it’s what you finally get your self respect from. I’m not a very good athlete; I have to do something well. So, what I do, I like to at least know that I can do it. And I guess that means winning. I play tennis, but I’m not competitive. All I want to do is hit good shots. I’m not out there necessarily to win. I think if you do something, you might as well do it to the best of your capacity. If you try and promote science, you should promote the science which is going to have an impact, rather than just science, per se.

Were there other things in schools that inspired you?

James Watson: I had some very good teachers at the University of Chicago. There was an Irish class. David Green taught humanities, and he was a marvelous teacher. Later on, you became inspired by scientists who were doing things that you would want to do. Certainly, Linus Pauling loomed large in my life, by the time I left the university. And there was a geneticist at the University of Chicago, Sewell Wright, who not only could do experimental genetics, but did evolutionary genetics. He was a powerful mathematician. He was certainly inspired, and I listened to his lectures at the university. It’s not necessary, but I think it’s very helpful to go to a university where people can inspire you. They can be heroes. Role models, if you want to call them that

You’ve said you like to be around people smarter than you.

James Watson: Yes, because it keeps you awake. I get bored very fast if I’m listening to somebody and I think, I know what the answer is going to be. I’d rather read a newspaper than listen to a dull lecture. So I’ve always been very conscious of people’s style and speaking. I mean people who can use words to convey information. That was the extraordinary thing about Robert Hutchins. He had a way of getting his point across through a certain amount of irony.

I like people describing things as they are, rather than as the way people want them to be. There’s a lot of evil in this world, and you’ve got to be aware of it. You shouldn’t just have illusions. It’s not only other people that are evil; there’s evil in your friends, in yourself, and you’ve got to put it in perspective. So, I expect the worse, and then I go under that assumption.

Then I’m never knocked off my perch, because I discover there are fallen heroes, or something. I go in pretty suspicious. I’m not the sort to say, “Oh, human beings are wonderful.”

In which case you’d be constantly disappointed.

James Watson: People say I’m very snobbish and, in one sense, I am. I just want to hear something interesting. Ordinary people are ordinary. When I was young I was always trying to get near extraordinary people. They were more like the extraordinary film stars. You get alive when you’re stimulated, so I guess I want to be stimulated. That’s really the sadness of this, there’s hardly a politician out there now who says anything in a way that I can respond to. Because they seem to be not talking about the world as it exists. That was the thing that made so many of us so fond of Adlai Stevenson. He had a certain style. It didn’t make him president, and he was often wrong. I can’t say that he was the good guy and Eisenhower was the bad guy. But when Eisenhower spoke, I found it hard to listen. You know, just another Republican. But Stevenson made you think that there could be something wonderful about human beings. I think that was the point.

Now is not the occasion to mention people who are in power, but I’d long for someone to give speeches like Roosevelt did. Roosevelt had marvelous speech writers. He had Robert Sherwood, he had Sam Rosenman, he had Archibald MacLeish. And he must have also liked the English language. He must have had a good English master at Groton, or something, someone who got across the fact that words say something. Sometimes, when things are bad you really need someone who gives you hope because they say things are bad. Because you know they’re bad, and people don’t say they’re bad and that’s, of course, why Hoover killed the Republican Party for over 40 years, because he kept saying, things were good and they weren’t good. Churchill saw evil and said it.

You’re going to slay the evil dragons and not just say they don’t exist. On my mother’s side, my grandmother was from an impoverished Irish background, and they always kept saying things were good. That was such hypocrisy. Maybe things in Ireland were so bad that you could never say what it was like. They called it blarney, I called it crap.

You always want to tell the truth?

James Watson: I guess I’m best known for just saying things the way I think they are under circumstances where you’re not supposed to say it. You’ve got a fairly short life span and, particularly when you have students, you’ve got to let them know what you think. They shouldn’t have a guessing game as to what you think, because you’re really out there to try and educate them as to what reality is. So, if you have a bad seminar, you might as well tell the guy to his face. You shouldn’t get up and say, “Wonderful talk,” when it isn’t.

Would you say science is no place for diplomacy?

James Watson: Sometimes it is, but not to the point of hypocrisy. I’ve certainly got into trouble a lot by saying what I think, but probably in less trouble than if I hadn’t said what I thought. You’re always getting into trouble, but that’s true of everyone. You’ve got to sort of calculate what gets something accomplished. You can’t go around having your language obscene. I remember when you’re in adolescence, everyone wants to speak as obscenely as possible. I remember that in Chicago. As you get to be adults, it occasionally was well to have words by which people know you’re upset.

I think the great thing about the University of Chicago was it didn’t place a great premium on good manners. I never saw them as bad manners, but the student body wasn’t forced to keep deferring to people for some reason or other. You’d just say it as it was. So it was a very stimulating place where you argued all the time, and you didn’t listen to something which you thought was wrong and just say, “Well, I don’t want to upset anyone.”

How much of a role has luck played in your success? Does it play a role?

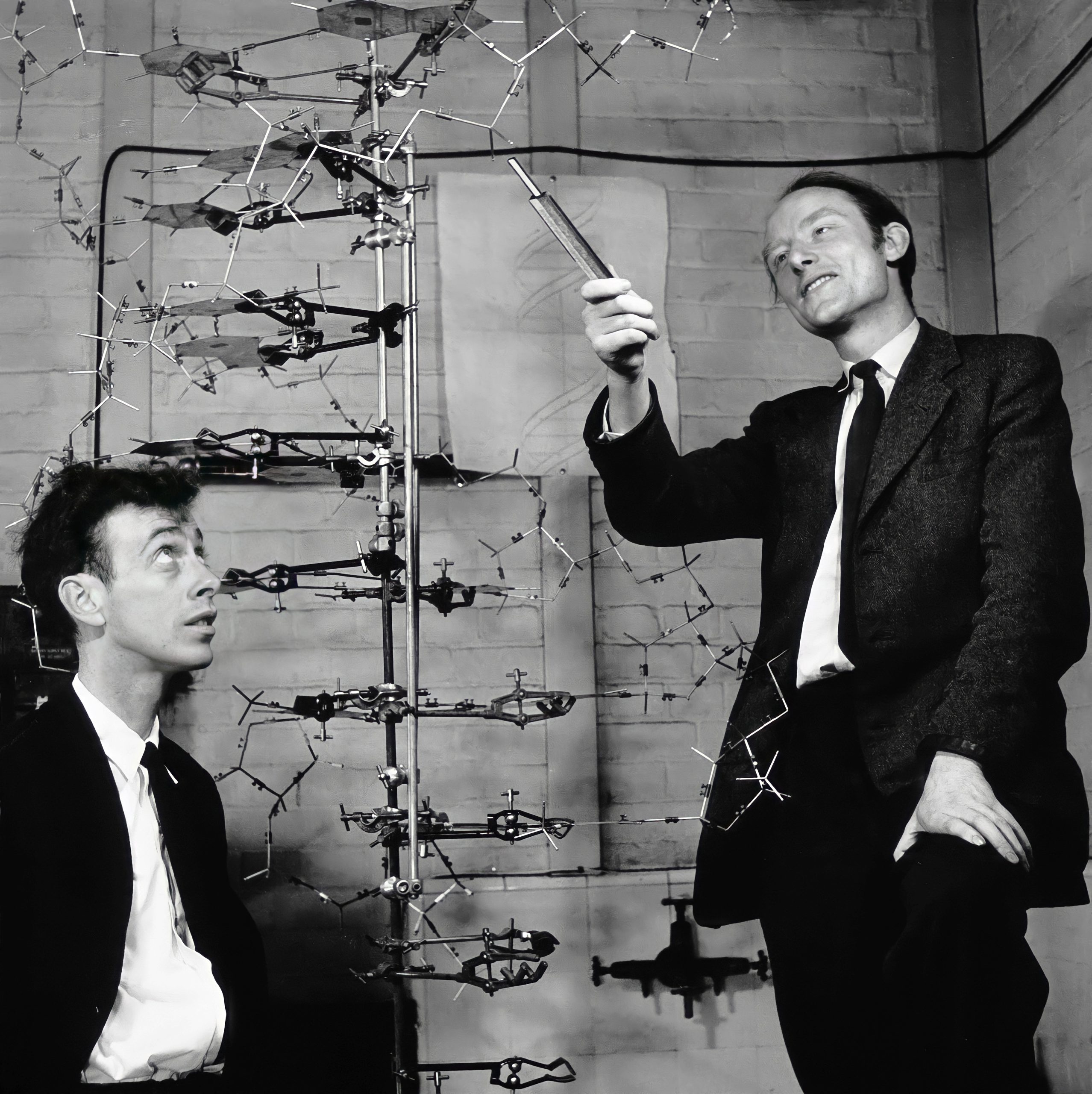

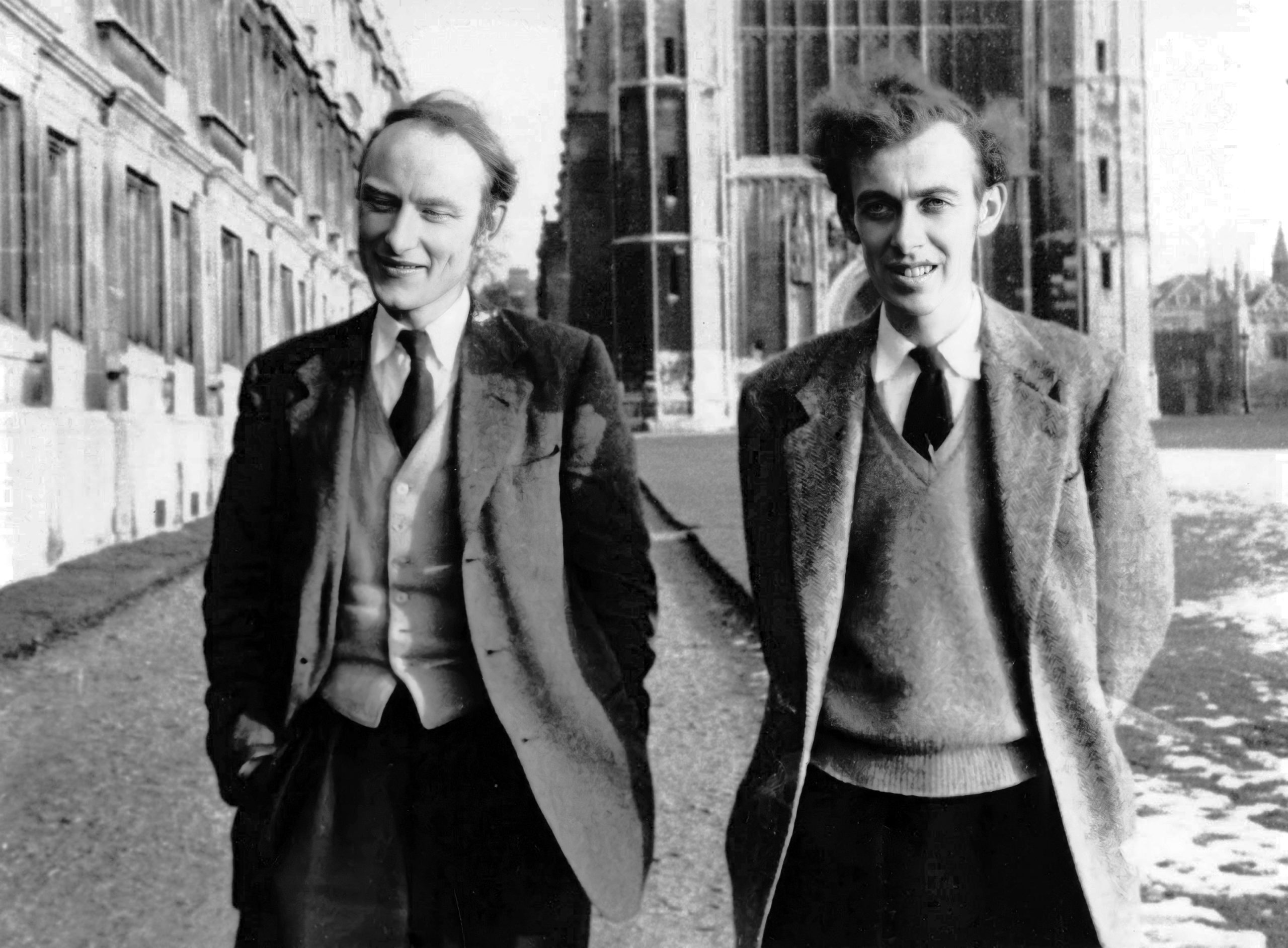

James Watson: Of course it does. When I went to Cambridge, England, I could have arrived there and Francis Crick wouldn’t have been there. And if Francis Crick hadn’t been there I wouldn’t be here right now. Now you could say it wasn’t luck, in the sense that Francis and I were both drawn to that particular lab in Cambridge, because it had an intellectual objective. It was the place in the world to go, there was no doubt. But it was partially luck that I got there. My teacher at Indiana University, Salvador Luria, had gone to the University of Michigan by accident and met someone from that lab in Cambridge, and said I was dissatisfied in Copenhagen and wanted to go to England. And he said, “I’ll take him.” So, that was luck. Would I have discovered Cambridge and gone there if Luria hadn’t gone to give a talk? You can’t say. I think you’ve got to be prepared for your luck by being part of cultural traditions which make you aware of what you should be seeking. You know, I think I’ve always wanted to go to places at the scientific frontier, and Cambridge was such a place.

You could say it was luck that I was born in 1928 and not four years later, because that discovery was going to be made in that period. Probably couldn’t have been made before ’51, but it was bound to come out. It might have gone two more years with people not focusing on it. But it was a discovery which was going to come at that time. Darwin had the idea of evolution, and he didn’t publish it. Then he heard that Voss had the same idea, and so he published it. When I said life is hard, I mean it’s not predictable. I could have gone to Copenhagen and fallen in love with a Danish girl and wanted to stay there even though science would have told me to get out of the place. That didn’t happen. So you could say bad luck in Copenhagen had led me to the right place.

Tell us about the moment you realized you had DNA?

James Watson: I thought maybe I’d get a girlfriend or something. Someone will think I’m worthwhile.

Did you fully appreciate it at the moment?

James Watson: Sure. But it was both Francis and I. After you did it, for a while your chief concern was to make the next step forward. Where would you go from there? I don’t think we spent much time congratulating ourselves. You had to go on to the next thing, that was really the dominant thing. I don’t think we were perceived as someone who tried to rest on our laurels. That’s not much fun.

Was there a sense of exhilaration at having finished that chapter?

James Watson: No. It so clearly solved a past dilemma, but opened up so many more that we were almost dominated. Where does it lead? It wasn’t any moment of mystic revelation that you might see in a Steven Spielberg movie. There wasn’t any of that. It was just, maybe my college will give me a fellowship, and I can stay in this world that I really like very much and thought was so extraordinary.

You walked through one door and there were 20 more before you?

James Watson: I’m a worrier you know. If you get one thing, you worry about something else.

You didn’t get the respect one might have thought from this.

James Watson: Oh, sure we did. What more could you do? Despite my personality, they gave me a job at Harvard. They sort of had to offer it to me. But I think many didn’t, because I was known for being so candid about things that it was thought that I would just upset things. I did, you know. I didn’t go there and stay quiet.

Is there anything you would have done differently?

James Watson: Not in any major way. Up at Harvard, I had extraordinarily good students, and I had met Walter Gilbert, who I worked with. Wally went on and discovered the DNA sequencing, so I’ve had very, very intelligent friends, and people that keep me honest.

You said it would be 50 years before there was a breakthrough in the cure for cancer.

James Watson: I’m not sure I ever said that. I think I said we need five to ten years more. Really solid cancer research, where you begin to think in terms of the genetic events, has been going on for almost 30 years, starting with the first molecular work on tumor viruses. I think in another 20 years we may know most of the basic things. We may really know what goes wrong when a particular four genes go wrong, and the biochemical consequences of these damaged genes, say in leukemia. One hopes that in some cases we’ll be able to use this knowledge to cure the disease. I think the possibility of this knowledge leading to cures over the next 25 years is not a far out idea. If I were running a drug company, I’d spend quite a bit of the company’s money to see if you couldn’t use this knowledge that the scientific world is producing to cure some cancers. I give it a 30 percent chance. I don’t think it’s a one in a thousand chance.

We’re learning enough of the basic science?

James Watson: We’re trying to learn the faces of the enemies. If you don’t know their faces, you don’t know where to shoot.That’s what we’re trying to do. I take enormous satisfaction in the extraordinary amount of good science that has been accomplished, that is still going on at an ever-increasing rate.

Did you experience any kind of setbacks in your life, and what did you make of them?

James Watson: After I found the DNA, I thought I found the girl I wanted to marry and then, after ups and downs, she said she didn’t want to marry me. It took a while to find someone else I could like equally well. So, you know, my life has not been that straightforward.

You haven’t had setbacks that caused you momentary doubts about your work or life?

James Watson: No, never that. In the sense of thinking I was in the wrong profession, or in deep mental gloom or anything like that, no. You could say I’ve had so much luck that I could always look forward to something. I think it’s when you can’t look forward to anything, then it’s probably easy to get depressed.

Have there been any tragedies that affected your outlook on life?

James Watson: Not very much. Things that affect me are things which affect the health of people I love.

What advice would you give young people who want to achieve something in their lives?

James Watson: Be very persistent to get to the place where it’s done the best. When you’re young, you don’t learn much from your peers. I probably succeeded because my teachers were more important than my school friends. That’s a hard thing to get across, but peer pressure when you’re young can often just lead to very conventional behavior. My parents were very supportive, so that I never really paid any attention to peer pressure. Not that I wasn’t popular, but I think this concept of trying to be popular is a very dangerous one. Popular girls in class, all these social things. When you finally see it, it’s pretty ugly.

And spending time just hanging around doing nothing?

James Watson: Well, I did nothing. I don’t think doing nothing is bad, because the brain has to relax. I spent an enormous amount of time as a child listening to baseball games on the radio. I think the most important thing is to want to know the truth and to accept it, and not to fight reality.

We have a tendency to do that.

James Watson: Yes. In America we have different cultural traditions, but we’re not tough enough on ourselves to accept reality. We want to look good. Looking good is more important than doing good. The politicians seem to be dominated by this desire to look like they’re doing good. I realized that you can become quite unpopular by trying to do good, as distinct from looking good.

I just read this book about Robert Hutchins, of the University of Chicago. He was the son of a minister, he was raised as a Presbyterian, but by the time he had grown up, he didn’t really believe in it anymore. His father probably was a marvelous speaker and the son became a marvelous speaker. Hutchins actually believed that you could arrive at the truth through thinking. He really wanted to believe some things were better than other things. He was a relativist. Logically, you can say there’s no one up in the sky to strike you down if you behave badly, but there’s an outrage when an injustice is perpetrated. If you don’t have that, as a civilization, you finally fail.

You can argue, what’s injustice? Probably most of us can agree on many cases of injustice. There was the Dreyfuss affair. You’ve got to have a society which is concerned with justice. It’s quite clear that American society for the past decade has been concerned with greed, not justice. Getting ahead, and not with being rewarded in some way by society if you do things which try and reveal the truth. I’m struck by this whole question of whistle blowing. They’re not liked. They’re regarded as nasty little whistle blowers.

We had to pass a law to protect them.

James Watson: Sure. There are a lot of people who say, “Society isn’t perfect and you can’t spend your time worrying about the injustice. Just get something done.” But why are you trying to get it done then? I’m amazed at the sloppy ethical standards among scientists. I think they have accepted so much of the corruption of modern life that they don’t realize it. If they don’t stand for the truth, who does?

What do you mean by sloppy standards?

James Watson: So much in science is priority. Who had the idea first? Claiming you had ideas when you didn’t have them. Being more concerned with whether you get credit than seeing that the credit is correctly assigned. Of course if you get credit, you get a job, you can support your children, so it’s part of the struggle for life. But, I guess because I’ve been at the top of my profession, I see most of my friends at the top are chiefly concerned with staying on top, rather than worrying about those who are less fortunate.

More concerned about themselves than how their work might affect others?

James Watson: No. Just not much desire to spread the wealth or share the wealth.

What responsibility does a scientist have towards society?

James Watson: Within limits, to give an impartial view of why things happen. That is, to say whether we are suffering from a greenhouse effect or whether we’re not. Whether nuclear energy is good or bad. Whether genetic engineering is good or bad. If there’s scientific knowledge which will affect human beings, we really have to work to see that the public understands this knowledge and gets the message. I think the people who were the most responsible were the so-called atomic scientists who, when the bomb came along, really did work very hard for some form of arms control. I think this group, largely of physicists, was a pretty responsible group. I think they lived up to what society hoped people would do. Of course it got involved with whether you should be dominated by worrying that bombs will explode, or whether the Russians will take over, and those sort of arguments. But, at least, I think your responsibility is somehow to be honest in your reporting of the scientific facts, and not bend the facts towards your political convictions.

Has criticism of your work had an impact on it?

James Watson: Sometimes, when I get into trouble from saying something at the wrong time, it makes me be slightly cautious. As a government official now, I am certainly aware that I shouldn’t be flippant. You can’t be cute, I’m perceived in a different way. I see my work as a very non-partisan affair, so when I go to Washington I try and stay out of overtly political acts or statements, because that’s not for me. It wouldn’t do any good anyway unless I decide, well, I can’t take it any longer, I’ll run for president.

Do you see any possibility of world starvation being alleviated?

James Watson: It depends on how many people there are. If we could stabilize the population, I think we can certainly solve the food problems. If you keep pushing the population to the point where food is always inadequate, you’re going to have starvation.

What about distribution?

James Watson: A lot of it is distribution, but again imagine four times more people on the earth. Maybe you could just do it, but then you’re going to get so many other problems.

The things you’re talking about in the biotechnology area have the potential for supplying more food.

James Watson: Sure. I’m sure that there are other people saying these techniques will be expensive, so only the big farmers will farm, but generally, it’s good or bad. One of the striking things that I’ve seen — it’s sort of everywhere — is that people want to get off the farm. In England they’re down to probably one percent farmers. Is this good or bad that there aren’t more English farmers? I don’t know. Farming is a rather dangerous occupation, you have all sorts of occupational hazards. Would it be bad in India if you didn’t have all these people living at subsistence level on their tiny little plots of land? That’s a good question. I would think, if the cities could take any more people, they would leave the farms and move to the city. So you’ve got to ask not some utopian view of what society should be like. A lot of people like to go to the cities.

Do you have any other thoughts about the next frontier?

James Watson: No. I don’t want to look stupid ten years from now.

(The Academy of Achievement had the opportunity to interview James Watson again ten years later, after the Human Genome Project had succeeded in mapping the entire human genome. The text of this interview follows.)

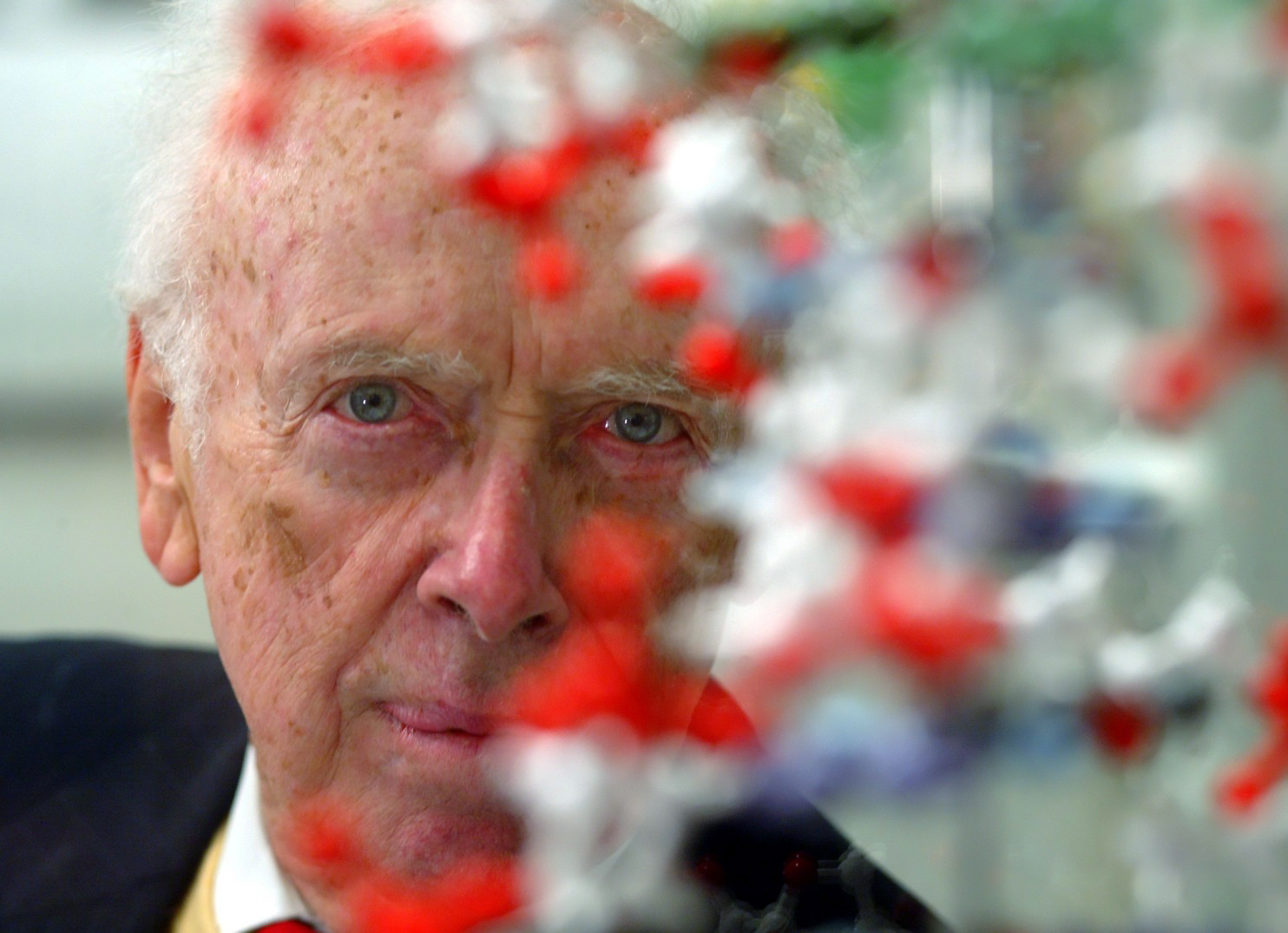

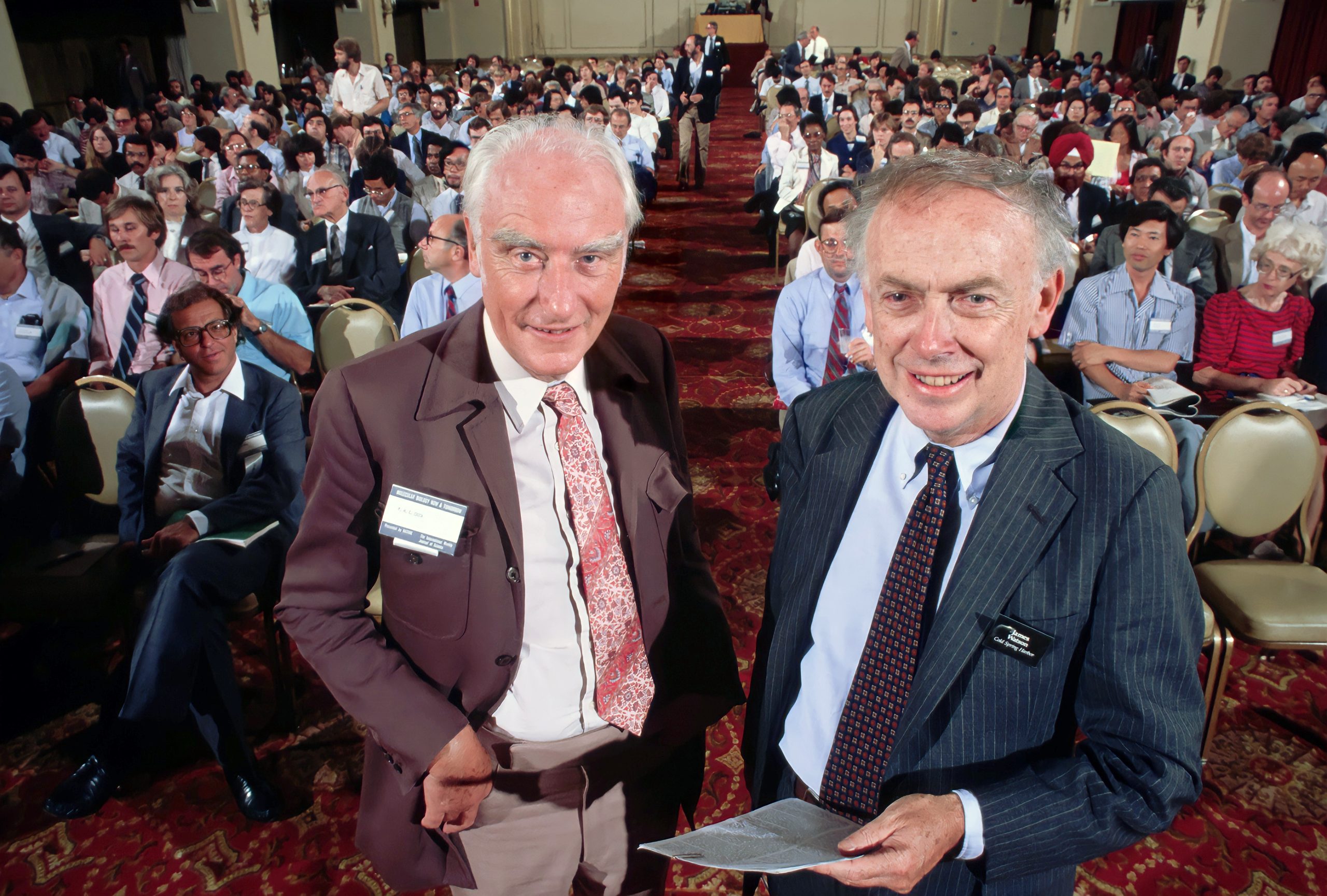

When you and Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA in 1953, did you ever imagine that the human genome would be completely sequenced in your own lifetime?

James Watson: I never thought that I would see the human message. We didn’t know how to read DNA then. It became possible in the mid ’70s. There were people in chemistry who said, “Oh, they can’t do that.” It was a very pleasant surprise.

How would you explain to the layperson what the Human Genome Project is all about and what your own role has been in this remarkable project?

James Watson: Well, the aim of the human genome project was to get the human genetic message, which is in a nice linear language — four letters and three billion pages — and just work out what the book is.

One should see life as consisting of a script, which is DNA, and the actors, which are largely proteins, which are described in the text to great detail. And so you’ve got a system of a play where you’ve got a script and you’ve got the actors, and you could say, “Well, who is more important? Shakespeare or Gielgud? Whose playing now?” And everyone’ll go back and say, “The actors are very important but scripts are more important.” So we’re getting the script for life and, you know, every species has its own script. And initially people said there’s just too many letters and it costs too much money. And so starting about 15 years ago we got together and said, “It won’t cost that much. We could do it for $3 billion but it would take us 15 years,” and you know, back of the envelope calculations was pretty good! It took a little less and its cost was about what we said it would be.

So you weren’t surprised that the genome was sequenced within that 15-year period?

James Watson: Well, it helped when competition came along. People said the script is so important, let’s get it first and get it copyrighted or patented and sell it to people who want to read it. That pushed the people who were going to give it away free to work faster, and both efforts came out roughly at the same endpoint a couple of months ago.

How have the improvements in technology facilitated the actual sequencing of the genome?

James Watson: It is the reason we have this technology produced in a combination of academic and commercial laboratories. When we first talked about the human genome project, it was done by hand, just like when we had monks copying books, they make mistakes. So the machines really reduced the mistakes. You don’t have a human error process in there and the boredom which leads to errors. So wonderful machines.

The biggest challenge in the wake of the sequencing of the human genome is how this information will be applied. What are the technical difficulties associated with this challenge?

James Watson: It’s like trying to read a book when you’ve only cracked part of the language. So I like to say we have major words and minor words. Words that are used over and over again in specified amino acids and we know those. So we can spot groups of letters that make sense collectively. And then there are a lot of letters that we can’t yet make any sense out of. And we know that some don’t make any sense. They’re there to serve as evolutionary garbage. But a lot of them do, such as, “Does a gene start functioning at the time of conception?” “Does it only begin to work when you’re ten years old?” These are the sort of signals we’re trying to find now, which is, you have a gene, when, where and sort of why do they work and turn out. So in one sense we’re at the start, but at the other hand, we finally can see the actors, and that’s a big step. But you can hardly go to a play and watch it if it has ten actors who are important, so only a couple really are important. Even the simplest cells, they have 500 actors, and just seeing who talks to each other and do they have fights among each other and all this sort of thing. That’s a very big job, and at that level it will be understood only in the simplest cells to start with, let’s say in bacteria.

The human play, let’s say, takes 70 years and has, we guess, maybe around 30,000 actors, and it’s going to be a long time before we really can understand the significance of a lot of these scenes that are occurring. When the instructions aren’t quite right, something goes wrong in your life. You know, the Dolly — the famous cloned sheep. Three years into its life it suddenly got an appetite that’s unquenchable. So something in its instructions isn’t quite right.

This Human Genome Project has some exciting implications for medical research. What are some of the advances in medicine we can expect to see in the next decade?

James Watson: We know a lot of the bad actors behind cancers, enough so that I’d say we have a realistic chance to cure most cancers certainly within your lifetime. Maybe not within mine, but if I was 50 years old, I would think maybe that’s not going to kill me, maybe we could just die of old age.

What about psychopathology and other mental disorders? We might throw in Alzheimer’s disease.

James Watson: Alzheimer’s is one where we have had a lot of help from genetics of finding families where the disease occurs early and this has led to finding actors that — bad actors who we want to control. And so the drug companies are hard at work and the first drug is being tested now. It just might work, you know, to prevent it and I would think In 100 years we should be able to control Alzheimer’s. I mean, we have got to control it much sooner because as we live older senility just is —you know, by 90 half the people are out of it. The brain isn’t functioning very well but in a few it’s functioning perfectly, so it doesn’t have to get bad. And I’m sure we’ll find out all these things. The next 100 years is going to be extraordinary, what we are going to find out about human beings, and I have no doubt that human lives will be healthier and happier.

I think we’re already beginning to get great dividends in understanding the origins of some diseases that affect the brain, but so far we don’t have really good drug targets for schizophrenia or manic depressive disease, but I’d be very surprised if we don’t have them in ten years, and a lot of people are working very hard to get them over the next couple of years. So without the Human Genome Project I’d say understanding mental disease at it’s molecular level would have been an impossible task. But with the Genome Project we’re going to understand it, and if you understand it you just have this general optimistic faith that you can do something about it, and that’s seemingly the case in cancer, and with Alzheimer’s we have got some drugs that just might stop the disease.

Haven’t they actually isolated some of the genes that are responsible for at least some forms of Alzheimer’s?

James Watson: I think for the majority now. There are some rare “early onset” Alzheimer’s where the genes are easy to find, and then there’s the “late onset” Alzheimer’s, the one that affects most of us or our friends, at least half of us. And a very key gene has been found, so I’m optimistic.

What do you consider to be the most serious ethical issues confronting the use of information from the Genome Project? There are some obvious issues regarding health insurance.

James Watson: Well, I look at it another way. I think our biggest ethical problem is people won’t use the information we get, and I think that’s just as bad, to let a child be born with no future — when their parents certainly would have not wished to have such a child — but had not been genetically tested to show the risk. I think that’s totally irresponsible, and of course it gets into this right to life question. Is all life equally valuable? I don’t think it is, in the sense of people like to have a healthy child. And if you’re — you know, have a bad throw of the genetic dice and you’ve suddenly got a child that you’re going to have to take care of, it’s bound to seriously lower the quality of your life, as well as the suffering caused within the child.

People keep saying, “Oh, you’re going to try and direct the future.” But I would love to direct the future because — you know. Weather prediction, I think, you could make arguments. “Oh, you’re going to spoil your future because you know the week you’ve chosen for a holiday it’s going to rain.” Well that’s better than not knowing that, and it is sort of saying we can look into our future. But of course, we’re only looking to our future so we can do something about it. So I don’t think any of us, you know, want to know the date of our death or anything like that, or how we’re going to die. But if we knew we were going to die in a rather awful way unless we do something about it, we want to do something about it.

So as a biologist you just regard some people as lucky throws of the evolutionary process and others — you know? Evolution only occurs by creating variants, and a lot of variation is harmful to the individual who carries it. So evolution is not a kind thing, and we’re all products of evolution. Well society, you know, says we’re products of God. We’re products of evolution and it’s very different. You know, a just God wouldn’t have done anything which didn’t have a purpose. But I think like most biologists, we don’t think there’s anyone to answer our prayers and change the course of destiny. So, I mean, scientists and doctors, you know, have this right of change — have this ability to change the future. In that sense we are the gods, and people are, of course, afraid of evil gods, and then for some people, you know, my way of speaking right now is just totally inappropriate and sacrilegious, and you know, in some countries they’d shoot me, or just — You know, saying there’s no one up there in the heaven telling us what to do, but I don’t think there is.

What role do religious issues play in the whole issue of the Genome Project, and why is it people are so reluctant to confront those issues?

James Watson: I think because they don’t want any attempts to stop the project, and just figuring, “Why unnecessarily get enemies?” Eric Lander got up and said, “I’m not a eugenicist.” Well, I thought, “What hypocrisy!” I mean, you might not use the word, but of course you would like to change the future when the future is bad. And there’s a difference. Who is controlling the future?

I think all genetic decisions should be made by women, not the state, not their husbands, just by women, because they’re going to give birth to those children, and they’re going to be the ones most responsible. And let them decide to the extent that we have the ability to decide. But when my little book came out, they excerpted a chapter in Germany and it was in the Frankfurt newspaper, and I thought it was perfectly sensible, but it came out and the head of the German Medical Society was saying, you know, my views were those of Hitler, and so on, but really all I was saying was women should have the choice whether to have a child who will be seen as a bad throw of the genetic dice. That’s all I was saying.

I think it was partly religion and partly the Germans saying, “We misused genetics and so we’re not going to use it ever again.” Most of my friends just go ahead and work out the script, but they don’t want to say how we’re going to use it at this level. Of course, the outside world does, and when we started the program I said, “We’ll spend five percent discussing these ethical issues.” So…

When you go out, people say, “What about super babies?” I said, “None of us know how to produce a super baby, but what would be wrong with a super baby?” And if you could have kids brighter than yourself, you always want to have your kids have opportunities you didn’t, and this sort of saying, “Oh, we can’t! We shouldn’t try and enhance life because we’ll make the spread between those who are lucky and those unlucky even greater.” That’s a very, rather nasty view of human nature. I think we would actually try and help the people at the bottom. And it’s always, you know, “The rich are going to get richer,’ and, you know, our current tax bill is pretty upsetting because you’re thinking the rich get richer, and so I don’t like that. But I think, you know, those people really don’t want homeless people on the streets because they’re schizophrenic. That’s not very nice to live with. I mean, those people—it’s not nice. So we’re trying to help those people. I think you’ve got to sort of assume we’ve succeeded as a social species because we really do like each other. We’re not fundamentally nasty. The nasty people are the exception. Of course, you know, in individual lives we have our good moments and we have some bad moments, but I think one should see genetics in an optimistic way, not a pessimistic way where you’ve got to stop everything.

Where would you draw the line in genetic research? What sort of research is technologically possible that you would agree shouldn’t be pursued?

James Watson: I wouldn’t stop anything. Now it looks like cloning would likely lead largely to defective human beings. So a law against that, I have no objection, because I can see harm being done. That is, I don’t see the need for a clone. But if you said there’s no harm, I just think, when you really ask who is trying to stop these things, when they say bad things, they are generally people who don’t want genetics to be used at all. For the most part they’re people on the extreme left or right who, for ideological reasons, political doctrine, religious doctrine, don’t want genetics as an important factor in the way human decisions are made.

Many other species now, the mouse, C. elegans, for example, or the fruit fly, are being or have been sequenced. How do you see this information as ultimately benefitting our understanding of the human genome?

James Watson: Well, we wanted to get the scripts for simpler forms of life because of understanding the evolutionary process, and also becaus many of the mouse genes will function the same way they do in humans, so you can do experiments on the mouse that you can never do on humans. Getting the mouse will allow us to probe human disease better. Doctors wouldn’t want to experiment on mice per se, but it’s to understand ourselves and that’s why we study the mouse. What should be the impact of the Human Genome Project? The biggest impact would be it’s going to make people realize we’re products of evolution. We are.

What’s your view on the true number of human genes? We’ve had estimates going from as high as 100,000 now down to a more conservative 30,000. Does the answer to this question really matter?

James Watson: I don’t think it matters that much. I think we were first surprised, but then rather relieved. In some cases people discovered we really knew the genes already in particular things. The smaller the number, the easier it is to find what you’re looking for.

People were first surprised humans didn’t have any more genes than a plant. But I think the way to look at it is “plants is dumb.” It can’t move. It has no nervous system. Whereas really, we’ve advanced by a few key genes giving us a nervous system which can do these extraordinary things, let Beethoven and Shakespeare and Rembrandt, et cetera, come into existence.

There’s not a Rembrandt gene. There was just a brain which was put together in a very good fashion. So when you want to find, you know, the uniqueness of humans, it’s not going to be a gene. It’s the human brain, which is put together with lots of genes, but it’s the brain we want to understand.

Do you think there will ever be another revolution in molecular biology as big as the discovery of the structure of DNA by you and Francis Crick?

James Watson: I don’t see how there could be. Now we want to find the language of the brain, you know, how information is stored there, and I see that as a major challenging problem and I don’t know where the answer will come. Somewhere in the brain is, you know, the telephone number of our house. How do you write a telephone number in the brain? So there are great problems, so I don’t think young people should feel, you know, “The DNA revolution is big and I can’t be a part of it in that sense.” Just go on to something else.

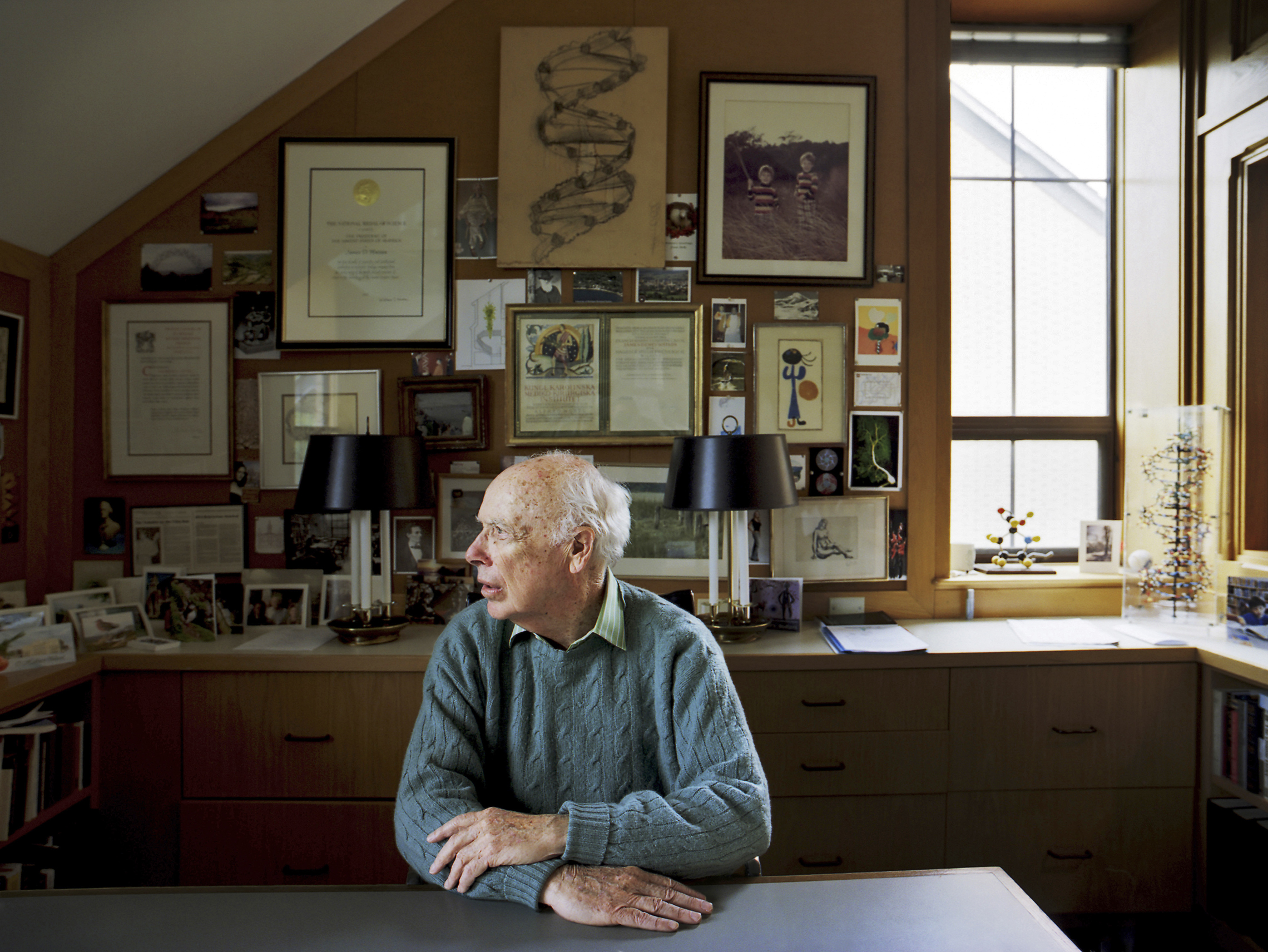

What new projects are you taking on at the moment?

James Watson: Oh, I’m too old to start anything new. I’m trying to improve my tennis game.

And how is it?

James Watson: Getting better. When I was young, I thought people 50 were hopeless and now, at 73, I think people at 50 are still hopeless. I like to think. I love seeing biology advance. When I first came to Harvard so long ago I was bored most of the time. There weren’t that many new facts appearing. There were so many things I couldn’t understand, and I didn’t know how to attack them. It has become so much easier to attack the problems which I once was interested in. When we don’t know how to attack them, they seem up in the clouds somewhere, but it’s all about pulling them down from the clouds so that you can actually have a whack at them.

Now that you’re at this stage in your career, are there any problems that you would like to have tackled that you never had a chance to?

James Watson: No, I think I’ve been pretty lucky. I wanted to do the gene, and I wanted to work on cancer. At Cold Spring Harbor we’ve been working on cancer for 30 years, and with lots of nice insights as to things we couldn’t have predicted. I think scientifically I’ve had a very charmed life. My rule was, you know, just go to a place where there are a lot of bright people, and try and surround yourself with bright people and they’ll keep you alive. And so at Cold Spring Harbor there are lots of bright people. At Harvard there was — well. wonderfully bright students. Some faculty are bright. And then when I was educated I had super teachers. So, you know, the message I would give to young people is: “Don’t be the best in your class. If you’re the best in your class you’re in the wrong class.”

For a number of years we didn’t really seem to be going anywhere, and then around 1960 it clicked. We had a wonderful period from, say 1960 to 1970. That’s when I was here at Harvard. But I think you just always want to know what big problems are out there and what might be the way to climb the mountain.

Can you identify a characteristic style or mode of thought that has been particularly useful to you in your scientific work?

James Watson: I think it is just saying what I think instead of being afraid to be at variance with other people. Even bright people can seem effectively to be stupid. I think you’ve got to be at home in being out of place. Because for the most part people don’t want you around. Young people probably — you know, if they’re any good they’re thought arrogant. And that means they think they know the truth and they don’t believe those above them. So, you know, You’re not supposed to be arrogant, but if you’re not arrogant, if you don’t believe you know how to do something better than someone else, you’re probably not doing anything. So you know, it’s not that I felt arrogant but I’ve thought — well, probably people feel I’m arrogant — but I’m just thinking that other people aren’t doing what they should. Francis Crick used to upset so many people, and that was what I thought his great virtue was. But you know, when you’re young and you upset people, you don’t get the jobs, you know. A really great university is willing just to go out and get people even though they upset other people. But if you see department politics, often it is not as simple as you think to get someone in who has upset some senior person by saying the senior person is going nowhere. So I think my job now is to criticize those who are 50, the people who are running things, the people who pass out the money.

If you could travel ahead in time, say 500 years, and look back, what sort of scientific problem that’s unsolved today would you love to know the answer to?

James Watson: I don’t think I can see that far ahead. I’ll put it just this way: I want to see how you write memories in the brain. Just saying you strengthen a synapse, that’s not the answer. Strengthening synapses certainly helps, but a key thing is, how do you write “four” and how do you retrieve it? Centuries ahead, it will still be fun to be a biologist.

On behalf of the Academy of Achievement, I would like to thank you for a most fascinating interview.