Was there a person that inspired you when you were growing up?

Story Musgrave: When I was very young I led a life of isolation. We had a thousand-acre farm and really didn’t have any visitors. They either weren’t permitted, or didn’t dare come into that environment. So I can say it was myself and the universe out taking a walk.

What about a teacher?

Story Musgrave: Later on I did have teachers who were really spectacular, great humans.

I had a great teacher, Frederick Avis, in biology. I first did some surgery as a teenager. Did some really good research in biology, in transplantation of fertilized eggs. We were the first to do that. It’s not much, nowadays you’re transplanting genetic material, but back in the late ’40s it was a pioneering effort

That was in high school? What high school was this?

Story Musgrave: This was St. Mark’s School in Southborough, Massachusetts. Yes, that was in high school. I took care of the rabbits, of course, because I was the farm boy who could do magic with animals. I can still do anything with animals.

When you say you can do anything with animals, what does that mean?

Story Musgrave: I have a great relationship with animals, and with children. I get to their level. I try to see the way a child looks at the world, it’s hugely different. The way other creatures see this environment is hugely different. We look upon our environment and think that what we see is reality, and that is not true. This environment — this room — is not reality, it is the way we are designed to perceive it. A bat flying around in this room, would perceive it very differently, because a bat is looking at ultrasonic information.

With animals, or birds, or children, I will try to see it the way they see it. To have that kind of empathy, and then to communicate in that way. I try to transcend my own self, and my own parochial biases.

If we ever start communicating with living creatures from other planets, the number one priority is, how are you going to communicate information? Even between different cultures here on Earth, you get into communication problems. To see people and dolphins working together is unbelievably exciting to me. I think of how we’re going to communicate with creatures from other places, and that’s an unbelievably exciting thing.

From what I’ve read, you wouldn’t be surprised if that happened.

Story Musgrave: The statistics of life out there and the statistics of intelligent beings and advanced civilization is a certainty, the way I look at it. It has not been accepted, because we’ve been in an anthropocentric era. People have wanted to place themselves in a totally unique position, because they mix up physical uniqueness with faith and meaning.

Statistically, it’s a certainty that it is out there. When we look at our own environment, at the way life has come into being here on earth, we only have one data point here. Instead of looking at this marvel and assuming that it is absolutely unique in a universe that has billions times billions of galaxies and stars, the first assumption should be that the rest of the universe is the same as this.

To look at one data point and say, “The whole rest of the universe has got to be different than this one,” does not make logical sense. But it’s been that way, through this anthropocentric era. “I am the center of the universe, the universe goes around the earth, and me.” Once you’ve transcended that, then common sense would say that the creation and evolution of life into complex and intelligent creatures is probably a cosmic imperative. It is probably a force. If you want to get into science, it’s the second law of thermodynamics. These things will happen.

Now, I think it’s a certainty that that has happened and is happening. The other problem though is distances, and scales, and times and light years. You’re going to try to communicate with beings which have long since passed, and you catch their…by the time you get their message they will have gone by. That planet may not even be in existence, by the time you get the message.

That scale somehow…and I believe it’s also possible, although of course I can’t say how, but we need to somehow transcend the distances that we see and the speed of light. But I also think that we shouldn’t rule that out, that’s a possibility.

What books were important to you as a child?

Story Musgrave: I never read a single book as a child. I did not read as a child. I worked on the farm. I had books in the classroom, but that was it. I never read a single book outside of the classroom.

What books were important to you later on?

Story Musgrave: Later, of course, I devoured books. I always have one with me. I like reading, in general, but literature is my number one, the thing that I like to read the most.

You’ve talked about having a strong connection with some of the American writers of the 19th century, what did Emerson and Thoreau mean to you?

Story Musgrave: Both Emerson and Thoreau, and in particular for myself, Whitman, the American transcendentalists, they went out into nature to find God. Their spirituality was in nature, even though Emerson was a preacher on the pulpit, he ended up going out into nature for direct, face-to-face communication with God, if you want to call all of this creation part of God.

Thoreau, of course, did the same thing. Whitman expressed the whole universe in his poetry and in his catalogues. That attitude almost defines what we call American romanticism, or American transcendentalism. I feel particularly close to them, because I am now out in the universe. I’m in a position to see nature from another point of view, to be outside the earth and see the big picture. To have an absolutely clear shot at the skies and to see stars that you can’t see from down here, Magellanic clouds, auroras, a new perspective of nature.

You can go back a hundred years earlier to the British romantics, the Lake Poets, Wordsworth and Coleridge, Shelley and Keats, and you see the same thing, whereby people come face to face with the universe. They are looking for direct revelation and communication from God’s creation.

It’s clear to see why I like the English romantics and the American transcendentalists. I like their poetry as literature but also, from a philosophical point of view, I have very close ties to them.

You’re a poet yourself. What’s the connection between poetry and space?

Story Musgrave: I think the experience of space needs to be communicated in terms of what is in one’s head and one’s heart. Most of our history in space has been communicated in terms of action — what people do, a chronological list of events which have transpired — as opposed to the human experience of having done those things.

It’s one thing to be out working on the Hubble Telescope and doing the ballet that you do to run the tool as expertly as you can, but what’s the experience of operating the tool? What’s the experience of getting ready? And what’s the experience of a great pass over South America?

I can relate almost the entire earth to you in terms of what a South America pass is, of what a Shark’s Bay, Australia pass is. I can just roll that through my head. I think we need to capture what that experience was, and then get it into the right form.

Poetry is its own medium; it’s very different than writing prose. Poetry can talk in an imagistic sense; it has particular ways of catching an environment. Meter, rhyme, rhythm, alliteration, structure, all of those things are tools for bringing out the senses.

Space takes almost a new language. It’s a new place. We created and evolved here on earth. We’re earth-based creatures, and the magic of what goes on when you take humanity out there, it’s going to take a new language to do it. And poetry has some tools in it which will, as music does, directly do you. You don’t have to intellectualize music. You listen to music and it works on you and you get it. So it’s a direct communication. And so, I think, a way of bringing space to people, that poetry will work. I’ve already written 300 space poems. But I look upon my ultimate form as being a poetic prose. When you read it, it appears to be prose, but within the prose you have embedded the techniques of poetry. I look upon that as a really powerful way to communicate the experience of space.

We’ve become used to thinking of space as the frontier, but now, being able to translate that experience to people who haven’t been there is kind of a frontier in itself, because nobody’s done it before.

Story Musgrave: No one has done it and, as an extension of my calling in space, it’s extraordinarily fitting. NASA has told me they’re not going to fly me anymore. That was probably a magnificent decision, maybe not for the right reasons, but if you look at it, it makes incredible sense, because obviously, I could have not stopped.

So I think it’s an extension of my calling. Also, I’ve always looked upon it as a responsibility. There are millions of people who could have done what I have done. I have always given it my best and, when the door opened, always went in. I did that part of it, but millions could have.

It’s a responsibility to have an experience up there, not just to do the doing. Since you are representative of humanity and there’s millions that could have done it, it’s a responsibility to, number one, have an experience and then get it into a form which does translate that experience and, as poetry works, you can hand over the same emotions. Not only the abstract concepts, but you can bring people to the same emotions which you had up there. And that’s a tremendous challenge.

You’re the first space poet.

Story Musgrave: Other people have written poems about space, but I may be the first person who has formally taken creative writing courses and poetry writing courses, and studied poetic criticism with a mind to acquiring the skills to do that, to the best of my current ability.

What is the next great frontier in space?

Story Musgrave: I testified about this before Congress 10 days ago. I think the next step should be low-cost, reliable access to space. Then space can happen for everybody. We have not made any progress on that in 40 years. It’s the same cost now as 40 years ago. We’ve upgraded some of the older missiles that were military vehicles but, in over 40 years, we have not come up with a new launch vehicle, whose intent is low-cost, reliable access to space.

That should be the number one priority, and we should launch it in five years. We should have very hard standards for the timeline and the decision process. We should have names and dates. Just get on with it and do it. Once we’ve gotten that cost down, that will open up space to all kinds of things which it’s closed off to right now.

That would democratize space in a way.

Story Musgrave: It will. If people can pay for it, all kinds of people will be doing it. At the current costs, it cannot be paid for by anyone else but the government. So it will help the government’s programs, but it will also help commercial and private programs and everything else. It’s the cornerstone. What energy does it take to get there? What is the cost that it takes just to get up there? That should be the number one priority.

What part of space touches people? Exploration, the reach to find out what this universe — this cosmos — is all about, what our place is in it. What does it mean to be us? What does it mean to be human? I think we’re going to continue in that vein.

So we’ll want grand observatories that will look way out there, into distant space. We’ll study the earth in all different kinds of ways. How might we be different if we had been created and evolved on some other planet, or in zero-G? I think we’ll see really exotic kinds of biological explorations. I think that’s the long term.

You’ve expressed a great interest in Mars. Do you wish you could have gone to Mars?

Story Musgrave: I was going to Mars in 1967. I joined NASA to go to Mars. Any hand I’m dealt, I will play to the best of my ability. So I might never have gotten to fly in space, or I might have gotten the six flights that I did. At the beginning of the moon project, we were nowhere. We had no infrastructure, we had one sub-orbital 12-minute flight, the first Mercury mission. Kennedy said, “Go to the moon,” and we launched the Saturn rocket the same year. There was only one year between the Mercury and Gemini programs. We’d say, “We’re going to do it now,” and two years later, we launched something.

The technical and scientific momentum, the courage, the risk-taking that we had then, the kinds of project management, for me it was totally reasonable to think that after 30 years of that acceleration I would be on Mars. That was the point at which I would peak out, that was my crowning mission to fly. I’d keep on going after that, but that was the one. It was reasonable to think that at that time.

I am a physician, and you’d want a physician on board going to Mars. I could work on physiology and life detection, all that kind of thing too. I don’t regret not going there, because I tend not to regret anything. You could say, do I regret not being on Magellan’s ship? I don’t regret that. I lived in a certain era. This is my era: 1935 to 2000 and whatever. This is Story Musgrave’s period in life.

If I’d never flown in space, I wouldn’t regret that. The only thing that I could regret would be when an opportunity comes my way, when a door opens, if I did not run with that opportunity. If I’m thrown the ball of life and I don’t run with it, I would regret that. Because that’s a lost opportunity, not having the courage or the energy to go ahead.

Has that happened?

Story Musgrave: Oh, I fail left and right. I fail all the time, but I learn from my failures.

How have you failed?

Story Musgrave: My failures aren’t that visible. But there are times when I don’t execute that well. I’m a very good planner, I’m a very good strategist, but in terms of accomplishing things, there are times I fall flat. I’m not a hard taskmaster. I love myself. I’m not that tough on myself. I’m very reasonable, and I always smile at my follies, the things that don’t work. I’m easy on myself in that regard. I have a sense of humor about it.

You’re racking up an impressive number of degrees. Could you recount what your degrees are in, as of May 22, 1997?

Story Musgrave: They’re in mathematics and computers, chemistry, medicine, physiology, literature, philosophy, and I’m working on two theses now, one in psychology and one in history.

As much as you’ve studied, you feel like there’s still much to study.

Story Musgrave: There’s a huge amount to study, but I think I am completing my formal education now. But for every book that I’ve read for a course, I’ve read two or three others just for the sake of doing it.

Despite all that formal education, I’m still a self-educated person. I’ve accomplished more in self-education than formal education, but my formal education does continue. I think I’m happy with where I am now.

With eight advanced degrees?

Story Musgrave: There’s a couple more coming, but it isn’t the degrees. Going to night school, as I have for the last 11 years, has been my culture. It’s been my theater, it’s been my opera. There’s things I’ve missed because I’ve done that, but it’s a choice. Everything in life is. You take what you want and you pay for it.

I’ve only taken things that I have a passion for, that I have a huge interest in. And after I’ve taken enough for interest, I see if I can fit these things into someone’s program, and I usually can.

You said there’s a relationship between history, psychology and space. That space is a place to study yourself and study the earth too.

Story Musgrave: I take my courses for the education itself, but since I have had the privilege of space flight, I have a responsibility to put it in perspective, to bring psychology to it, to bring history to it, to bring philosophy to it, to examine what it means. How do you express it? Why do it? How is it transforming humanity?

I’ve taken about 200 credit hours since 1986 — philosophy, literature, psychology, history, sociology — and in every single one of these courses, I have always had three spiral notebooks.

The top one is the traditional one for learning what is in this course. If I’m studying the existentialists, then I take notes so that I will know precisely, uncorrupted, what the person we’re discussing believed, what they said, and the professor’s remarks, and those of other students.

The second spiral notebook is: “What does this mean to Story Musgrave?” That’s a separate context. The third spiral notebook is: “What does this mean to space flight?” I take notes in all three almost like a pipe organ, but the bottom one raises the question: “This concept that we’re addressing in this class, how can it help me have a better experience in space? How can it help me express the experience of space travel better?” I have taken 200 credit hours in the humanities into the space flight context, and this is incredibly rich.

I’m very haunted by an image that you discussed in an interview of lying in the ocean before a space flight, and looking up at the sky. Do you literally get into the ocean?

Story Musgrave: Yes.

I have an urge to immerse myself in nature before a space flight. It seems to come together. The ocean is an incredibly powerful part of this. It’s a literal immersion to lie in the ocean, and to drink the ocean. It’s what space flight is all about too. You are going off into a place where you have a different point of view. It’s a different part of the universe, and you have a different perspective on it. So I always go swimming. It doesn’t matter that the last one was in December. I didn’t think about it being cold. You just walk in, and after a little while, it becomes just delicious. I’m there for hours, oblivious to the temperature. You can lie in it, and let the sun go down and there is the space ship with those great, powerful lights. These beams go by, and the shadow of the space ship makes these radiant beams going up into the heavens. You lie there and take in the other celestial sights, whether it’s a moon or stars.

I always look for satellites going overhead. I’m doing this geometry in my head. The ocean’s here, and I’m lying with toward the beach and the satellites go from west to east, and when I look to the left, there’s my space ship. You look at the speed of the satellites and know that tomorrow you will be one of them. It’s a form of closure in which this kind of existence, this experiential occasion, this meaning comes together in a marvelous way.

I do the same thing when I go to the launch pad. I’ve very often been the center-seater, the flight engineer on launch, who is the last one in. So I have an hour and 15 minutes out there all by myself to think what this is all about. I look through that space ship out into the ocean. I look for the alligators, the birds, nature, and I step back and think about human technology. I think about the amphibians, and how life came out of the ocean to the land. And we’re like the amphibians, leaping off. It’s an extraordinary, magical moment. It’s as good as being in space itself.

I have an hour and 15 minutes just to do that. Once I have to start moving, then I’m bringing my focus down into getting in my suit and harness the right way and getting into the details of doing things right. That hour and 15 minutes is similar to the night before out on the beach, in which I can just think about what space flight is, why we do it, what it means.

Tell us about sleeping in space. What is that experience like for you?

Story Musgrave: I’ve gotten a lot better at doing that. You have to leave your earthly self back here. It’s not just night, you know. The sun’s going up and down every hour and a half. Before going to sleep, I try to spend ten or 15 minutes thinking about how I’m going to have a creative sleep period.

Here’s another opportunity. I’m in space. I have an opportunity to do something different than climbing in a one-G bed and lying there. I could simply get in a sleeping bag. That’s the way it’s always been human space flight You get in a sleeping bag and you strap yourself in it, strap your head down and here you are.

I always try to do things that are unique up there, because it’s such a privileged opportunity. I spend ten or 15 minutes before I embark on sleep to think of something that I’ve never done before, to experiment.

You float, right?

Story Musgrave: At times. On my first flight, I started playing around with sleeping bags. I’d try them all different ways. But then…

On my second flight, one time we worked 24-hour day shifts, where you had one team work 12 and you’d work 12. They were banging around all night. And, with their banging around all night working, it was hard to sleep. I took a pill to help me to sleep and I forgot I took the pill. So I went off to sleep, nowhere, just out, floating around. You don’t get the head nods in space. Your head doesn’t fall, there’s no gravity to make that happen. So I went off to sleep, and actually I went floating upstairs where my buddies were, and they said, “Oh, a monster!” They threw me back downstairs. They didn’t tuck me in, they just played with me all night. I’m off sleeping with the pill, you know. I bounced around all night. And so from there I learned to float, just plain to simply float.

It’s just delicious to go off to sleep, in the twilight zone. You don’t know where earth is, it could be in any direction. You also don’t know where the shuttle is around you. You are not touching anything. It’s just a fantastic separation from everything. You go into the twilight zone, and occasionally these cosmic rays go through, so you have these little light flashes going off in your eyes.

There’s times, falling asleep, when you feel like you’re outside of the space ship. You see the earth, and you see the space ship going around it. It’s a huge meditation in which you can let go of everything and have no contact with anything. I’ll turn a little switch in my mind and I can turn my mind off totally, in an instant. Nothing, no images, no thoughts. I can accomplish that instantly, but I’m aided by that kind of environment.

There’s other ways to sleep too. On the Hubble repair mission, we had four space suits in a rather small closet called our air lock. Two of them were affixed to the wall, the other two were floating around. I’d swim up into their arms and get a bunch of them ahold of me. I might grab a leg over here, bend the knee, so I have several feet which are pushing on me and I’m wrapped up in several arms, and I go to sleep this way, being held in the arms of unoccupied space suits. That’s another way of trying to have a great sleep experience.

Are these suits that you designed?

Story Musgrave: I helped design those in the 1970s. Although going off to sleep with them, I didn’t think of them that way, I thought of them as people.

Doing that within this small closet, I didn’t expect to move or go anywhere. There’s one little window in the back. We get 45 minutes of light in there, and 45 minutes of night. Every time I woke up a little, I would find that I had rotated. It turn out that even with that many things holding me, I was rotating. Two of those suits and me were doing this dance all night.

A lot of times I’ll go in the laundry. I’ll take a bunch of laundry bags and curl up with them, and we’ll get stuffed in some corner. It’s like a water bed, but it’s a laundry bag bed at zero G.

Sometimes, as opposed to that kind of softness and floating, I will choose a very hard environment. I’ll jam myself in an aluminum corner, where there’s no room to go anywhere and the steel has got me contorted into some position. It may not sound nice, but it’s another opportunity, and I try to do it all.

What have been some of your most exquisite views from space?

Story Musgrave: If you close your eyes and you think about earth, you have this whole map or globe of the earth that’s human-created, with the cities and the countries all different colors. But over the last 30-some years, because of TV pictures, and IMAX and photographs, humanity is being transformed in how they look upon earth, and they’re getting to be very sophisticated geographers.

As an individual, the same thing happens. When you first go into space, you’ve studied geography, and you think of earth as a map. But then you look out and you get the real picture. The Hawaiian Islands, for instance. You get a real visual image of the whole chain of Hawaiian Islands and what they look like. You pass them again, and again, and again, but there’s a hundred different images, they move. There isn’t just one picture of Hawaii. What’s the sun angle? Sunset, sunrise, sun over head, what are the ocean currents? What is the weather?

It’s a huge, moving thing. So many images that it replaces the map in your head. And so, as you do this you eventually have an image of the earth in your head which is part map and part real. You get this montage of places that you’ve been over and experienced, and it’s the real stuff. And you fill in the rest with a map

If you talk about South America, I have to work hard to picture a map of South America, because I have passed over South America. I know what a South America pass is. I know what passes are over almost the entire earth now. I can sit here and play this incredible video in my head of what it’s like to make a pass over a given area. Right down to very small details. The more I do it, the richer this kind of experience is. I keep adding to it, and I get more and more defined in my details.

What’s it like to see the South Pacific from space?

Story Musgrave: The South Pacific is probably the most beautiful place for me. I haven’t been there yet, but I’m going there soon. Just because you haven’t been there on the earth, doesn’t mean you can’t fall in love with a place from space. When you look at the earth, you have an experience just as powerful as being there.

The beauty, the aesthetics, the different shades of blue, the coral atolls where a volcano has come up! The coral lives at a certain depth below the surface, the volcano sinks back down and it just leaves this kind of lagoon in the middle. The shades of blue, the green, and the beaches on both sides of these atolls! The beauty is extraordinary and you don’t see it so much your eyes or your head, as you perceive it in your abdomen.

This goes on all the way from the Philippines to New Guinea and northeastern Australia, and all the way to Hawaii, one coral atoll after another. Extraordinary beauty, these big patterns before you. It is just a wonderful place in the world, although each continent has its magic.

What do you now know about achievement that you didn’t know when you were younger?

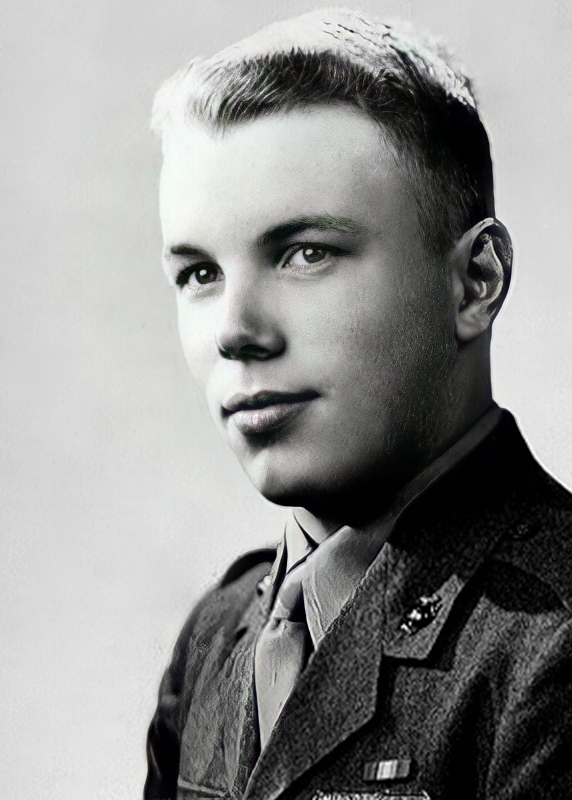

Story Musgrave: When I was younger my world was a thousand-acre farm, not even the county. My perspective was nature. That’s all I had. My horizons started to expand when I went off to Korea in the Marine Corps. As the saying goes, you join the service to see the world. That’s when my horizons began to expand.

And of course, with space flight, that is part of the human experience. The scale — the distances — are just extraordinary, and distance touches. Our repair mission was the highest that we go with the shuttle, 370 miles. When you’re looking at Florida and the launch pad, and you’re seeing a thousand-mile aurora, a thousand-mile shimmering curtain over northern Canada, then the scale of things is just huge.

You’re at the top of the telescope, with this six-story building down to the bay of the shuttle, that kind of expansiveness is just amazing. You haven’t gotten to Australia yet and you’re seeing the Great Barrier Reef. You’re seeing the entire continent. That is what space flight is all about. I think that’s part of what America is, and the roots of America.

It started of course with rediscovering America and the frontier. And wide open spaces and pushing on out there to new territories and exploration, up and down. Exploration, it’s just going beyond. It’s going from the known to the unknown, the familiar to the unfamiliar. Getting out of the comfortable path. Just pushing on, I think that’s what exploration is all about. Just going beyond the point at which you are now. Whether it’s physically taking a body out there, or pressing on to new realms of science, or new realms of human performance, such as the arts, or athletics.

To somebody who doesn’t know anything about this field, what has turned you on so much about space?

Story Musgrave: For me, life is 99 percent a spiritual quest. And it started in childhood with myself and nature, and the universe. And finding truth, finding serenity, finding myself by being immersed and embracing the whole thing that is part of us, that has created us, evolved us, that we are part of. Space flight has allowed me to extend that into unbelievable kinds of realms in which you see a third of the earth, in which you see entire continents, and you see patterns. And you come over the Near East and you see, framed in the space ship window, all of the civilizations, the old civilizations. And you see nature at work, and great, huge lines of volcanoes, from the tip of South America, all the way up through the Aleutians and Alaska.

It’s serendipitous that I was interested in that early on. Then had this opportunity to continue the quest on this scale, in a very new way, with a new point of view of nature. To take our organism, which has been created and designed by this environment, to put it in a new environment and to appreciate its struggle, and how it gropes with that, and to appreciate and actually enjoy the miscomparisons between how the body perceives this environment and what the mind knows. And to have his dialogue going on between body and mind, and to be comfortable with it, and even enjoy the fact that things don’t compare.

When you’re in space, do you get lonely for earth?

Story Musgrave: I don’t miss earth. I have not been to the moon, where the earth is the size of your thumbnail. The earth is hugely powerful and it’s got a hold on you. I don’t bother to eat in space, I stuff myself with things that will go down and get rehydrated. Every second that I have, or that I can steal I will go to the window and look at the earth. It grabs you aesthetically, it grabs you by its size, and its beauty and its patterns. You don’t miss it, because it’s there. It’s a different point of view. It’s in a different form.

When we go to Mars and to the planets, we are going to miss it. I do not think people, including NASA, understand what it is going to be like to see earth become the size of your thumbnail at 220,000 miles. In a day or two it will only be a bright planet. And then it will be a star.

I don’t think people realize how much they are going to miss that kind of contact. There are different scenarios, but if we were to go today, you would reach a point of no return. Once you’ve attained the velocity to go there, there’s no turning back, until you get there, loop around and come back.

When earth becomes just another planet out there, you’re going to miss earth. You are really going to feel that sense of detachment. We need to have some kind of virtual reality things on board to give you earth in an artificial way.

It sounds as if space flight has grounded you on earth, in the sense of loving and respecting earth.

Story Musgrave: It has, it’s given me a huge love of earth. But even as a three year-old I used to love to walk barefoot in freshly plowed, cool soil. I actually used to eat soil. It was just delicious, the mud, and the soil, and the animals, the whole thing.

Space travel has extended that to a different realm. It all plays together exceedingly well, but I do think the earth was the building block. It was the foundation for this organism going up there and having the perspective that I do, the sensitivities for what I feel and for what I see. And my whole approach, the way I think about nature.

It’s earth-bound.

Story Musgrave: Yes, it is earth-bound, and that’s what space flight does. The basics motivation pushing you out there is, in a way, an inward turn toward meaning. You can only find a self if you related to another. If it’s only you, then you can’t find yourself, you can’t define yourself. You really don’t know what you’ve got until you see another, and interact with another.

So going out into space is and exploring your universe helps to define who you are, and what a human is, and why.

What does the American Dream mean to you?

Story Musgrave: We have been a frontier culture. We were born out of exploration, we were born out of adventure. We were born out of the plains and the mountains. We’ve been a very physical kind of culture. And so, if you look at adventure, if you look at exploration, if you look at immersion in nature, a physical culture, and all those things, you can see directly how space flight relates to the way America has been born and how it evolved.

You must have a sense of pride at having been on all five shuttles.

Story Musgrave: I don’t really feel a sense of pride in having flown all the shuttles, or being the oldest person in space, or the other things that I’ve done. Those things are coincident with the fact that space is my calling. I have not just done it for seven or eight years, and then left, which is the average. I have looked upon it as my calling. I have tied it into my identity. I’ve pulled it into my childhood. It is part of my spiritual quest.

If I’d accomplished half as much in terms of the numbers, it would still be my calling, whether I flew three, or six, or one of the shuttles, or all of them. Whatever I have accomplished, the important thing is that it’s coincident with a 30-year calling.

You’ve been an inspiration to a lot of people. Most people in your field have left by the time they reach your age.

Story Musgrave: Yes, most leave. Some leave in their 30s, and most leave in their 40s. It’s been an incredible privilege. I think it’s been a source of hope for my colleagues. They see that, for me, life is better in the 60s. I’m also better in space. People who have seen me over the decades know that.

I am better now, as an astronaut in my 60s, than in my 40s because it’s a very complex business in which experience and perspective play a lot. You tend to scope out. You tend to know ahead of time what you’re going to have to learn to get that job done. It’s not a stick and rudder, it is not an instinctually reflective thing. You don’t just jump on things, you’ve got to study them. And it’s a very complex business in which experience counts. I create a lot of hope for people because they see, in fact, that not only am I better in my 60s, but I’m having more fun. They see a richer life. And so, I’m even amazed myself. I’m even amazed, too, that life is so much better in my 60s than my 20s.

I’m not fooling myself, because there are loads of other people that can see, the richness that you have, when you can bring wisdom and perspective into this business.

Have you had difficulty balancing family and your calling?

Story Musgrave: It’s a balancing act, there’s no question. It’s juggling, and it’s a matter of priorities and trying to make everything fit. At times I look back and wonder if I could have done things differently, I could have had a different balance. Like other professionals, your quantitative time with your family is diminished, there’s no question.

On the other hand, I did have quality time with the family. It was not, “I’m watching television and don’t have time for you.” I didn’t do that. I had incredibly intense, good, quality time when I was with the family. There’s no doubt there was less of that. Because I had a calling, they had to share that calling.

On the other hand, they have been able to participate in the same way a lot of professional kids do. Because their parents are professionals, they have been able to share, they have been on the edge of a huge number of disciplines, whether it’s books, or visits to the university, or going down for launches. My 10 year-old has been to four launches, and been through that entire experience. He has seen what I go through to do that. And he has been exposed to all the technologies that a young child can and people, and all those other things.

All in all, I think you at least break even. Even though you lose your dad to the calling, and don’t see anywhere near as much of him, I think the rewards in total balance out.

Where does the name Story come from?

Story Musgrave: Story was the last name a couple of generations back. My parents chose to use it as a first name and it fits. It’s something that you have to live up to. I feel a responsibility there too. I think it’s a wonderful name, but I do need to earn it and live up to it.

You need to tell the story of space.

Story Musgrave: Yes, I do. That’s a responsibility also, but maybe the name will help.

Thank you so much for talking with us. It’s been an inspiration.