Journalists are targets in a way that we were never before. There are regimes who don’t want freedom of press. They don’t want journalists revealing what’s happening inside their country. They’ve seen that when they kill journalists or when journalists are killed, no one does anything ultimately.

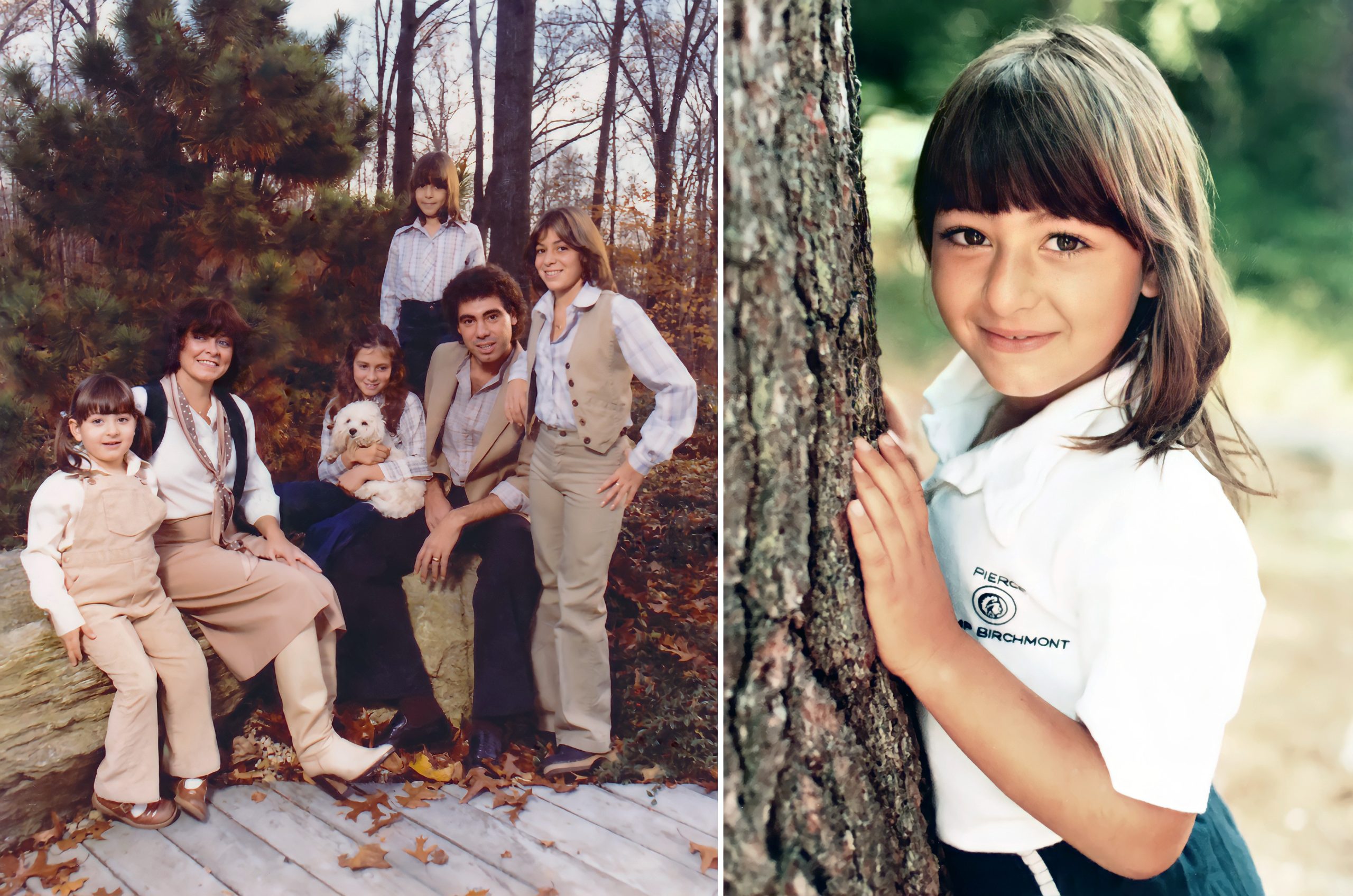

Lynsey Addario was born and raised in Westport, Connecticut, where her parents — both hairdressers — owned and operated a salon. Lynsey enjoyed a somewhat unconventional upbringing, with her three sisters, her parents, and her parents’ friends, many of them gay or transgender. Her father eventually moved in with another man, and she sometimes speaks of her “three parents — one mom and two dads.”

Her father gave her a used Nikon FG when she was about 12 years old. She bought a book on photography and taught herself to use the camera. As she tells it, she was too shy to photograph people, so she took pictures of flowers, cemeteries, and the night sky. Although she loved taking pictures, she never studied photography formally. After high school, she went to the University of Wisconsin, where she studied international relations and Italian, spending her junior year in Bologna, Italy. In the ancient university town, she felt free to shoot on the street and to take pictures of people for the first time.

After graduation, she moved to Buenos Aires, Argentina, with the intention of learning Spanish and trying to become a professional news photographer. She approached a 100-year old English-language newspaper, the Buenos Aires Herald, but having no experience, she was repeatedly rebuffed. As her Spanish improved and she continued to press the newsroom for an opportunity, she was told they would give her a job if she could find her way onto the film set where the pop star Madonna was shooting the film Evita. Addario talked her way onto the set and, although the pictures she produced were, in her words, “terrible,” she was given a job at the Herald.

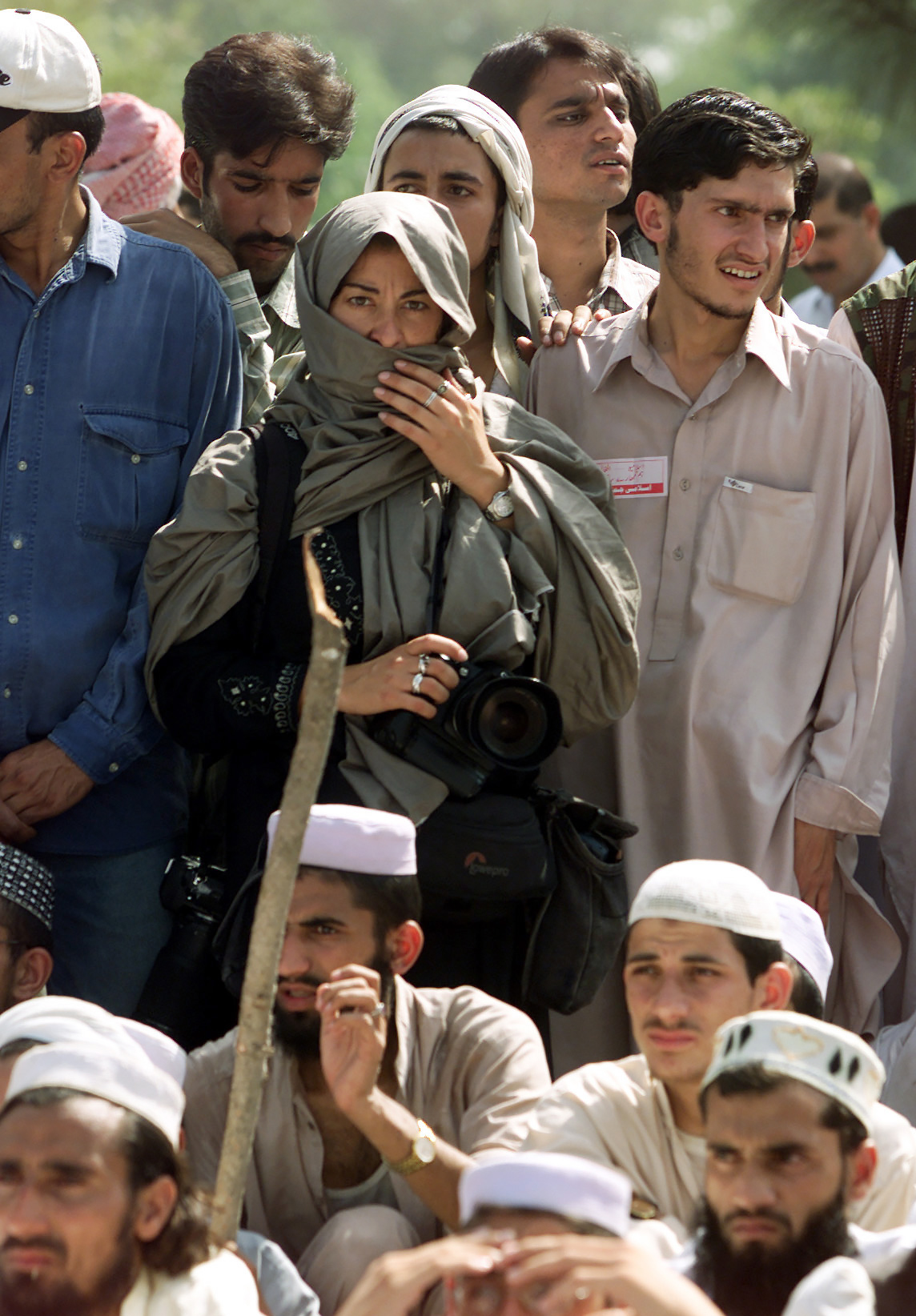

After a year with the Herald, she returned to the United States and settled in New York City, where she established herself as a freelance news photographer, working primarily for the Associated Press. Three years later, her appetite for adventure undiminished, she moved to New Delhi, India, reporting for the Christian Science Monitor, The Boston Globe, and Houston Chronicle. Her interest in women’s issues prompted a colleague to suggest she visit Afghanistan, where women were suffering under the oppressive rule of the Muslim fundamentalist Taliban regime. She made her first trip to Afghanistan in 2000, documenting the experience of Afghan women and gaining knowledge of the country, which would soon prove invaluable.

On September 11, 2001, the terrorist organization Al-Qaeda, based in Afghanistan, launched devastating terror attacks on the United States. Anticipating direct hostilities between the United States and the regime in Afghanistan, Addario immediately relocated to neighboring Pakistan. Entering Afghanistan covertly, she recorded the fall of the Taliban regime in the city of Kandahar. As American and allied forces pressed their advance, Addario learned the survival skills of a war correspondent.

In 2003, the United States invaded Iraq to depose the regime of Saddam Hussein, and Addario — seeing the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq as crucial stories of her generation — followed the troops. Following their initial victory over Saddam Hussein’s army, U.S. forces were drawn into a protracted counterinsurgency campaign. Addario recorded the experience of American G.I.s and the Iraqi population in vivid, unforgettable detail, spending most of the next two years in Iraq. In 2004, she found herself in mortal danger when she was kidnapped and then released by Sunni insurgents in the village of Garma, near the embattled city of Fallujah.

Having earned a formidable reputation as a war photographer, Addario traveled to Africa for the first time to document the refugee crisis in Darfur. There she first encountered the sight of an endless file of destitute, starving refugees marching across the parched earth in search of shelter, food, and safety. She would return to Africa many times to report on the continent’s conflict zones, but more and more, wherever she went, she turned her camera on the innocent non-combatants displaced by war.

Addario was living in Istanbul, Turkey in 2006 when she met the newly appointed chief of the Reuters Turkish bureau, Paul de Bendern. At age 33, Addario had never been able to sustain an intimate relationship amidst the constant travel and disruptions of her working life, but de Bendern, as a fellow traveling journalist, understood the demands of her career and a romance blossomed.

By 2007, Taliban forces had recaptured many areas of Afghanistan. Addario returned and was embedded for two months with the 173rd Airborne in the Korengal Valley. Jumping from Blackhawk helicopters onto the side of a mountain with the rest of the battalion, she traveled for a week on foot with 70 pounds of equipment.

At the end of a two-month operation known as Rock Avalanche, the 173rd was ambushed by Taliban forces. Addario documented the fighting at close range. The death of many American soldiers that day — in particular, that of a friend, Sgt. Larry Rougle — made an indelible impression on Addario. Returning from the front lines, she sought opportunities to portray the suffering of women and children in zones of conflict. In 2008, she received a grant from the United Nations Population Fund to document the use of rape as a weapon of war in the Democratic Republic of Congo, formerly known as Zaire.

The following year would be a momentous one for Addario. Addario shared in the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting awarded to The New York Times staff for its coverage of Afghanistan and Pakistan. That same year she was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship — the so-called “genius grant” — which pays the recipient a stipend of half a million dollars over a period of five years. In making the grant, the MacArthur Foundation cited her depiction of “the underlying realities of war” in Iraq and Afghanistan and “the lives of women in male-dominated societies.” That same year, while returning to Islamabad, Pakistan from an Afghan refugee camp, Addario was involved in a serious car accident. Addario’s collarbone was broken and her driver was killed. On a more positive note, in 2009, Lynsey Addario and Paul de Bendern married.

De Bendern hoped to start a family, although Addario found it difficult to imagine balancing the demands of her career and motherhood. At the same time, she became increasingly concerned with the challenges faced by mothers in the countries she visited. Addario decided to use the support from the MacArthur Foundation to conduct a multi-country study of maternal health in the developing world. Her travels took her to Sierra Leone, a West African nation with one of the highest rates of maternal mortality. There, she encountered one of the most harrowing stories of her career.

In a government hospital, Addario met Mamma Sessay, an 18-year-old woman who had traveled by canoe and ambulance for over six hours between giving birth to a pair of twins. When Mamma Sessay hemorrhaged after giving birth to the second child, there was no doctor available to treat her in time. Addario pleaded with the hospital staff to treat the woman, but in the end, all she could do was record the final moments of Mamma Sessay’s life and accompany her body on the long journey home. Addario’s essay “Dying to Give Birth: One Woman’s Tale of Maternal Mortality” appeared in TIME magazine in 2010. The story provoked worldwide outrage and inspired the Merck pharmaceutical company to commit half a billion dollars to a new initiative combating maternal mortality — Merck for Mothers.

In 2011, Addario traveled to Libya to cover the civil war raging between the regime of Muammar Gaddafi and anti-Gaddafi rebels. Addario and her colleagues entered the country behind rebel lines and followed the advance of the insurgency from one city to another. On March 15, Addario and three colleagues from The New York Times encountered a government counter-offensive and were returning to the rebel stronghold of Benghazi when they were overtaken by Gaddafi’s troops and taken prisoner.

Gaddafi had told his troops all foreign journalists were spies and should be killed. The soldiers moved their bound and blindfolded captives from place to place, threatening them with imminent execution. The male hostages were repeatedly beaten, and Addario was subjected to humiliating pawing and groping. After five days, while the outside world waited for news of their fate, the journalists were released into the custody of Turkish diplomats.

While in captivity, Addario resolved that if she ever returned safely to her husband, she would try to have a child. At age 37, to her surprise, she conceived almost immediately. Concerned that editors would stop offering her assignments if they know of her pregnancy, she hid it as long as possible. While carrying her child, she traveled on assignment to Senegal, Kenya, Somalia, and Gaza. On one of the last days of the year, she gave birth to a healthy boy, Lukas de Bendern, in a London hospital.

For three months, she devoted herself to caring for her newborn son, but in the following year, she covered stories in Mississippi, Mauritania, Zimbabwe, Sierra Leone, and India. Her work has now taken her to more than 70 countries. Although she still reports on armed conflicts, such as the civil wars in Syria and South Sudan, she now keeps her distance from the front lines, for the sake of her family.

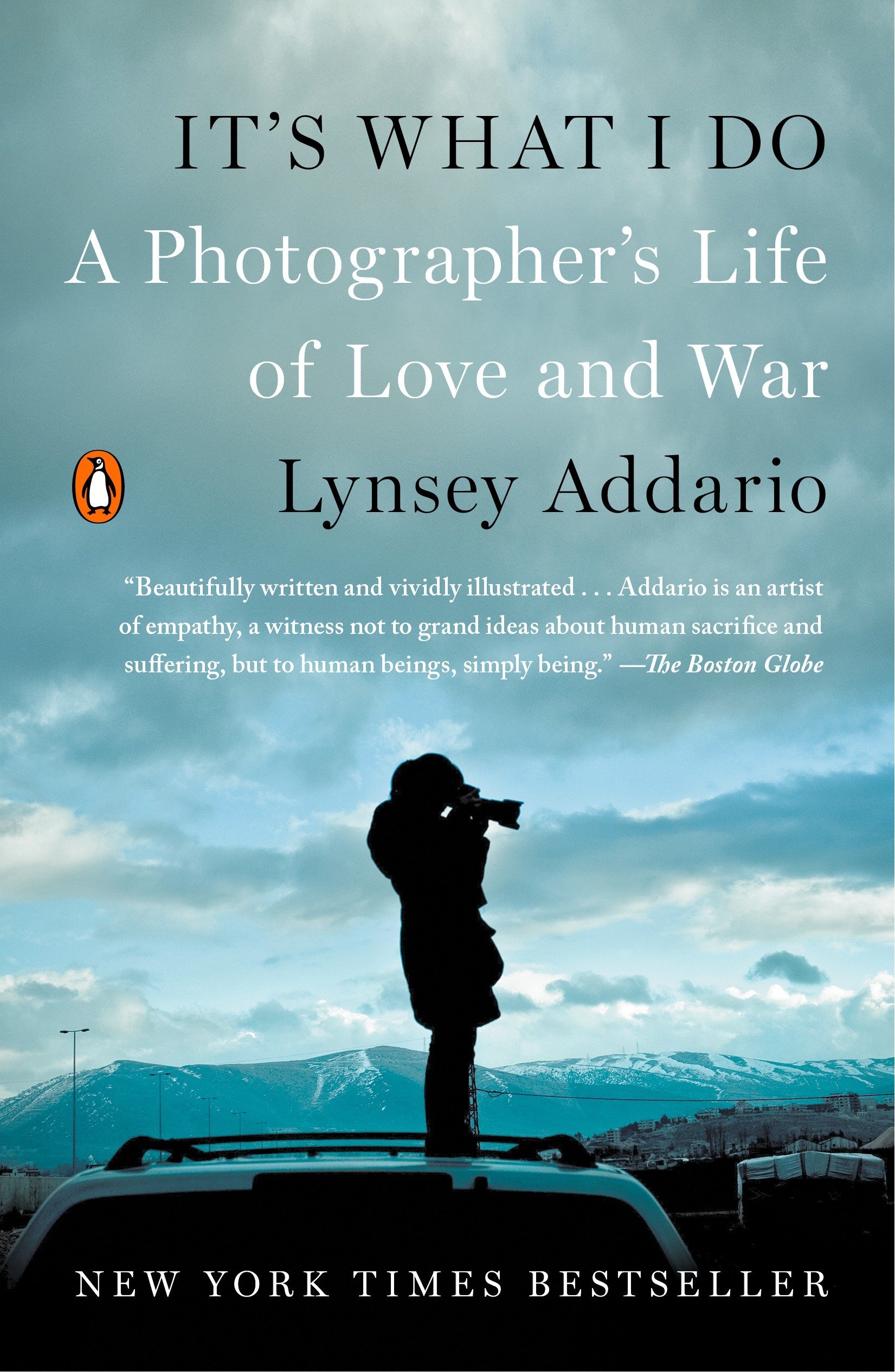

Her photographic essays — many exploring the lives of refugees and displaced children — appear regularly in TIME, The New York Times and National Geographic. In 2015, she published a remarkable autobiography, It’s What I Do: A Photographer’s Life of Love and War. Steven Spielberg is reportedly developing a motion picture based on her autobiography, to star Jennifer Lawrence. Meanwhile, the real Lynsey Addario’s latest book is simply titled Of Love and War (2018).

In February 2022, in the days before the Russian military began its assault, Addario traveled to Ukraine on assignment for The New York Times. She has been photographing the Russia-Ukraine war as it unfolds, capturing the disastrous consequences inflicted upon the country and its people, as well as the bravery of ordinary citizens who have joined in the war and humanitarian efforts to protect their country.

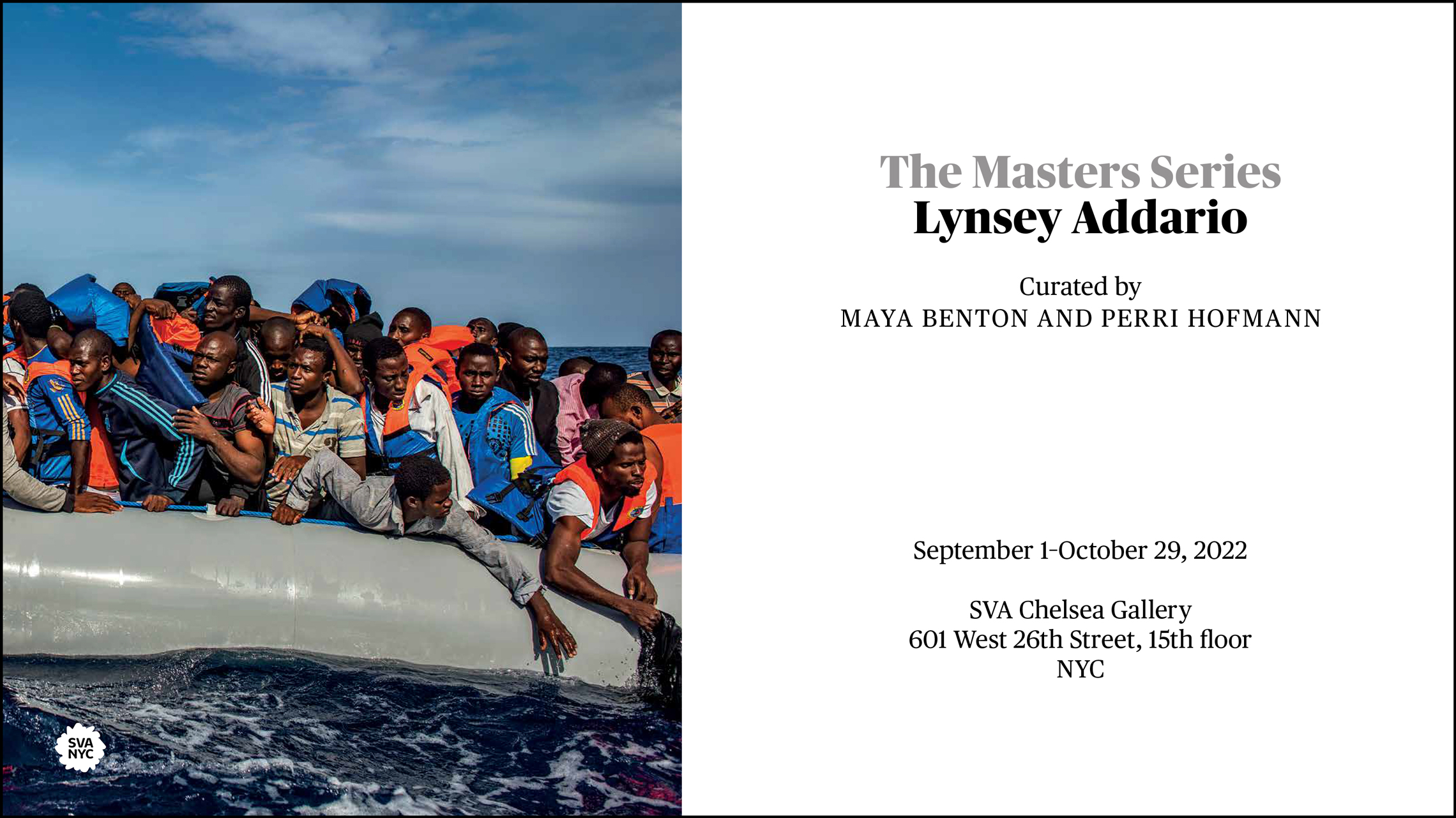

Photojournalist Lynsey Addario has covered every major conflict and humanitarian crisis of our era, including wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Darfur, Lebanon, Libya, Syria, Somalia, South Sudan, and Congo. Many of her award-winning stories have focused on the experience of women in traditional societies and children driven from their homes by war.

Addario was a member of the New York Times team awarded the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting for the photographic essay “Talibanistan.” In making the award, the Pulitzer committee noted the perilous conditions under which the work was performed, but danger has been a part of Addario’s career from the beginning.

She first visited Taliban-controlled Afghanistan over a year before 9/11. In Pakistan she survived a car crash that killed her driver. During the Libyan civil war, she was held prisoner for five days — beaten, groped, and repeatedly threatened with death. She has recounted her life and harrowing experiences in a bestselling memoir, It’s What I Do: A Photographer’s Life of Love and War.

Your work has taken you into war zones and many dangerous situations. In 2011, you and three New York Times colleagues were taken prisoner in Libya. Can you tell us how that came about?

Lynsey Addario: We were in Libya covering the uprising, and the way it worked was the front line — Gaddafi’s troops and his military — were pushing in from the west, and the journalists and the rebels were pushing from the east. And the front line was basically a kilometer-and-a-half — or maybe a mile — in between the two. So all the journalists, including myself, who were covering the rebels entered Libya illegally without visas. That was the only way to get in and cover the rebels. So that was an issue, obviously, because aside from being shot at or mortared, the real danger was running into Gaddafi’s troops because none of us had visas. And Gaddafi, he kept saying repeatedly that all journalists are spies and if you see a journalist, you should kill them. So his military was trained to basically kill journalists.

So when we were covering the front line, I was there for about two weeks, and basically covering it as cities fell, and pushing forward with the rebels. On this particular day — it was March 15, 2011 — I was working with Tyler Hicks, Anthony Shadid, and Steve Fellow, and we were in two vehicles. That is a preventative mechanism; in case something goes wrong, we have a backup vehicle. So Anthony and Steve were in one car, and Tyler and I were in another. The front line was pushing in very quickly. We knew the city would fall. As a war correspondent, you learn these signs. Mortar rounds were literally falling onto our position, the position we were with, with the rebels. And civilians were fleeing. It was the first time that we actually saw women and children out of their houses, and they were leaving en masse. And there were leaflets falling warning people to leave.

So at that point, we were covering the fighting on the front line, and we pulled back into the city, just to sort of regroup. And when we pulled back, Anthony and Steve’s driver stopped the car and dumped all of their stuff on the sidewalk and said, “My brother was just shot. I quit.” So now we are four journalists and Mohammed, our driver, in one small car. So we filled the car with all of our stuff. And the other danger, of course, is that you have four journalists and four people who have very different needs. So everyone sort of wants to do something different, and the front line’s coming closer and closer. At that point, we went back to the hospital and checked civilian casualties and did some reporting there. And more and more people were filing out of the city. I remember I saw a group of French reporters and photographers — Laurent Van der Stockt, who’s a photographer who’s been shot, I don’t know how many times — and he looked at me and said, “It’s time to go. I’m leaving.” And at that point, I said, “Oh, no. If you’re leaving, we’re definitely dead.” Because you never let a French reporter leave before you. That’s just sort of a joke.

So he leaves, and we all get back in the car, and there was a decision made to go back to the front line. I was very uncomfortable at this point because I felt like it was time to go. But I guess, as the only woman in the car, I also felt like maybe I’m just being scared and maybe my instincts were off. Because, for whatever reason that day, I had a really bad premonition. So we went back to the front line; everyone jumped out of the car. I was trying to shoot, but I was kind of paralyzed by fear. At that point, Mohammed, our driver, got a call saying Gaddafi’s troops had entered the city, and we started hearing sniper fire. So once you hear sniper fire, you know they’re in the city because they’re not that far. So we stayed, continued working, and our driver started saying, “It’s really time to go.” He was sort of screaming. Then finally, we got back in the car after I think he had gotten two phone calls at this point from his brother saying, “Where are you? You have to leave.” His brother was working for the BBC. So we finally got in the car, and we started to pull back.

As we were heading back toward Benghazi, I saw soldiers on the horizon, and they were wearing uniforms, so it was different from the rebels. And it didn’t make sense because, of course, Gaddafi’s troops were coming from the west, and we were heading east. So I said, “You guys, I think those are Gaddafi’s guys.” And they started laughing, and they were like, “No, there’s no way. They’re behind us.” And suddenly, as we got closer and closer, it was clear that it was Gaddafi’s guys, and they had flanked the desert. So they went all the way around the desert and cut the road in front of us.

So everyone started screaming something different. Tyler was screaming, “Don’t stop!” Anthony and Steve — everyone was just screaming. Mohammed stopped the car at the checkpoint and jumped out and said, “Sahafa! We’re journalists.” At that point, it was complete mayhem. The rebels that we had been covering started opening fire on the checkpoint, and we were literally in a wall of bullets. Mohammed, I never saw him again. He jumped out the left. I was sitting on the left-hand side behind him. Tyler, Anthony, and Steve jumped out the right, and as soon as they got out of the car, one of Gaddafi’s troops was on each of them, sort of pulling at them. And because there were bullets everywhere, I was sitting in the car, and as the only woman — this happened to me in Iraq, too — I sort of always get left. They’re like, “Do we kidnap her? Do we leave her? What is she? Who is she?” So they sort of just left me.

So I’m sitting in the car, thinking I have to get out of the car because it’s not armored. I knew that the bullets were coming from behind me. So I made a decision to crawl across the back seat and jump out the same side as my colleagues. When I got out, one of Gaddafi’s guys was on me, pulling at my cameras. I was instinctively just pulling back, sort of fighting with him in the middle of the crossfire. Then finally, I said, “Okay, I have to. Obviously, this is ridiculous.” So I let go of my cameras. I let go of one camera. And the other camera, I still had because I remember I was trying to pull the disks out as I was making a run for it. I remember I pulled them out, and I don’t remember if I ever was able to put them — I usually put them in my bra. But I remember pulling them out as I was running. Anthony tripped and fell in front of me. I remember looking at him, and he was screaming for his life. And I thought, “Okay, this is as bad as I think it is. I’m not just overreacting.”

So we all made it behind the cement building. And when we got behind the cement building, the adrenaline was going. All of Gaddafi’s guys were sort of surging with adrenaline and very angry and brutal. They all starting asking for our passports. So we handed over our passports. Now, I had two passports on me because I always have two passports as a journalist. But for whatever reason, I think that day — because, in a war zone, we travel with everything in case you can’t get back to a city — I had both passports. So I had one in my underwear and one in my waist pack. So when they asked for my passport, I handed one over.

They told us to lie face down on the dirt. And each one of us had a barrel of a gun put to our heads. I think they were AKs because they were long barrels. We were sort of looking up. I remember looking over and we were all begging for our lives. They were about to execute us. They had taken my shoes off — I had Nike sneakers on — and tied my ankles together and my wrists behind my back. At that point, the commander came over and said in Arabic, which Anthony later translated, “You can’t shoot them. They’re American.” So they didn’t shoot us, and instead, they continued tying us up, and they emptied all of our pockets and found my disks. Never found my — I had $8,000 in cash and an extra passport in my underwear that I had for six days. They never found it. So then they placed me and Steve in one vehicle and Anthony and Tyler in another, in the middle of the front line, and kept us there tied up for like four or five hours and basically just laughed at us while bullets and bombs and everything landed on us and we couldn’t do anything. We were just sitting there, basically waiting to die.

What were you thinking? What thoughts went through your mind?

Lynsey Addario: What am I doing here? Why do I care about Libya? I can’t believe I’m going to die in a place like Ajdabiya! What’s my grandmother going to think when she finds out that I died in Libya? Will I see my cameras? What were my last frames? I hope they were good. Will they make it? You know, it’s not a linear — What will my husband think? My parents? And then it’s this guilt. You know that you’re putting the family through extraordinary trauma if you even live. And if you don’t live, it’s the same. Then one of Gaddafi’s troops came over. Actually, before Steve got in the car with me, one of Gaddafi’s guys came over and sat down next to me. I thought he was going to bring me water because often in the Middle East when they see a woman, they bring you water. And he just clocked me square in the face! I remember seeing stars and thinking, “Oh, it’s like the cartoons.” Because it’s the first time, of course, that I’ve been punched in the face. Because as a woman, I’ve never been punched. And I thought, “Okay, now I know where the cartoons come from.”

Steve got put next to me, and then another troop came over — another soldier came over — and he was talking to his wife in Arabic. I understand a fair amount of Arabic. So he had his wife on the phone, and he put the phone to my ear while I’m tied up and just sitting there. And he said — and his wife said — I think she said, like, “You’re bad!” And I said, “No, I’m a journalist.” And she’s like, “You’re bad!” She kept saying, like, “You’re bad!” And I was like, “No. Sahafa! New York Times. Journalist.” And she was just like — and then he started laughing and took the phone away like, “See? I proved my point. We have prisoners.” Then they moved us from the front line and threw us in the back of tanks, and that’s where groping really started. We were in the back like sardines in a tank, and I had a guy behind me spooning me. We were all kind of lined up like this, and the guy behind me was very aggressively touching me. Anthony, Steve, and Tyler were all getting beaten. Steve was having a gun sort of shoved between his legs. We were all too scared to talk, so we just said — Steve had a sort of tactic where he said, “Is everyone here?” And we all just said “yes” to make sure that we were still together because we were blindfolded.

Then we were put in prison in Sirte. We were tied to the sides of the military aircraft and flown to Tripoli and beaten. We were beaten on the tarmac. I think I was groped by pretty much every man in Libya. By the time we got to this VIP prison in Tripoli, we still didn’t know where we were, but we assumed as much. The foreign ministry took us over, and there was a guy who spoke perfect English who sort of said, “Okay, now you’re with the government of Libya, and we won’t hurt you anymore.” Whatever. But of course, we were put in, like, an apartment with bars on the windows. They said, “If you look out the window, we’ll kill you.” And they brought us food and water. But on the fifth day, the no-fly zone was obviously implemented because we started hearing French jets. At that point, we thought, “Okay, they’re definitely going to kill us now because there’s no reason not to kill us.” So it was sort of the uncertainty. You’re not told anything.

Anthony, very wisely, took a remote control and turned the TV on, and he found CNN. And the four of us — our pictures were on the screen. It said something like, “The Libyan government cannot ascertain the whereabouts of these four journalists,” or something to that effect. I looked at the screen, and I started to cry. I just burst into tears because I realized they were denying that they had us, so of course, everyone thought we were dead. So I said — I started crying, and I said — “Don’t you have families? Just let us call our families. You can keep us as long as you want, but at least let us make a phone call.” And they were like, “Madam, stop crying. Madam, please stop crying. It’s okay. We can’t let you make a phone call.” And I was like, “We have families!” So then they put us in the other section of the apartment and in rooms. When we came back, like an hour later, there was just a wire dangling where the TV was. So of course, they cut us off. But then, that night, we were woken up at like two in the morning, and they said, “Okay, you each get one phone call.” I couldn’t remember my husband’s phone number. Of course, my mother never can find her phone in her purse, and my dad doesn’t answer the phone. So I thought, “Who am I going to call?” So I was nominated to call The New York Times.

You couldn’t remember your husband’s phone number?

Lynsey Addario: No. Everything was on my phone, and everything had been stolen from us. We lost everything.

What did you say when you got The New York Times on the line?

Lynsey Addario: It was Susan Chira, and I know Susan, and she was like, “Lynsey!” And I was like, “Susan!” And there was a guy — I mean I was tied up and blindfolded, and they made the call and put the phone to my ear. And there was a guy literally, like, breathing on me to say, “Don’t you dare say anything.” And I said, “Susan, first of all, can you tell my husband I love him. I forgot his phone number.” And I said, “We’re fine.” And she was like — I think that’s basically — apparently, they had gotten a warning that we would call. And I just said like, “We’re okay. We’re alive.” Yeah, that’s it. I didn’t want to say — I was scared to say anything. I mean the thing about being captured is that you’re terrified to say anything or do anything. So there was a lot of psychological trauma that went into it, a lot of psychological torture. They threatened us with execution over and over. And the second — they would do things like start to be very nice to us and then beat us again. Or do something like, “Tonight you will die,” but say it while they’re sort of touching my face in a very tender way. So really twisted sort of ways of manipulating your mind so you’re just terrified all the time.

How many days were you gone?

Lynsey Addario: That was about a week, so it was six days.

Has that experience affected your work?

Lynsey Addario: Yeah. I read a lot of stories about people’s kidnapping and torture, and in my opinion, we got off very easy. It was fine. We were very lucky to be alive. Mohammed, our driver, was killed. So it affects my work in the sense that now I’ve been kidnapped twice. So now when I’m working in a place like Iraq — even if it’s northern Iraq and someone who hasn’t survived those two things would just drive on these roads and say, like, “Oh, this is great” — but of course, for me, all I see is ISIS around every corner. Or I envision the road filling up with insurgents because I’ve seen that, and I’ve been in that situation. So it affects my work in that sense, that I’m more paranoid than I ever was, certainly than I was in my 20s.

You also survived a bad car accident. Do you ever feel like you’ve used up a lot of your nine lives?

Lynsey Addario: I think I’ve used like 25 of them. I’ve definitely used up my nine lives.

How did it change your work to have a baby?

Lynsey Addario: Look, I think by the time I decided to have a baby, I had been kidnapped twice, was in a car accident, two of my drivers were killed, my two friends were killed in Libya — Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros — Joao Silva had lost his legs. A lot happened in very quick succession. I think I naturally felt like I needed to pull back, and maybe that’s one of the reasons why I decided to get pregnant then because I was 37, and I had Lukas at 38. So I have not been covering combat recently. I haven’t covered combat in a few years. I’ve been in South Sudan. I’ve been under fire. But I’m not like — it’s a very different time, also, in history. A lot of the reasons why I was going into those war zones was because American troops were there and on the front line, and I felt like it was very important for the American audience to see what was happening. So for me, in my head, there were very specific reasons why I was going to certain places. I’m not just a war junkie. I don’t just go wherever there’s combat. Now I feel like I was very torn about not being in Mosul, but I didn’t go because I felt like it was extremely dangerous, and I just couldn’t do that to my family.