They let me in, and I started studying. Then they kicked me out because I didn’t show much possibilities. And then, I was rescued by my fellow students in the classes that I was in because they got to like me. They thought I was a little crazy guy, but they got to like me. And when they told me — when the authorities said to me that “You won’t be coming back because you didn’t show any possibilities,” my friends, on their own accord — not mine, I had nothing to do with it, but they kind of liked me. And a committee of them, like three of them, went to see the head person. And they said that “We understand that Sidney is not going to be coming back.” And so-and-so said, “We just wondered. We know that you’re going to be doing a student production. And we figure that since he worked so hard to try to be acceptable, we wondered if maybe you could give him a walk-on.”

“Maybe he can just walk across the stage once.” And the person said, “Well…” because she recognized that they had developed some kind of feeling for me. And she said, “I’ll think about it.” And when they went back to her, she said, “I’ll tell you what, I’ll make him an understudy for someone.”

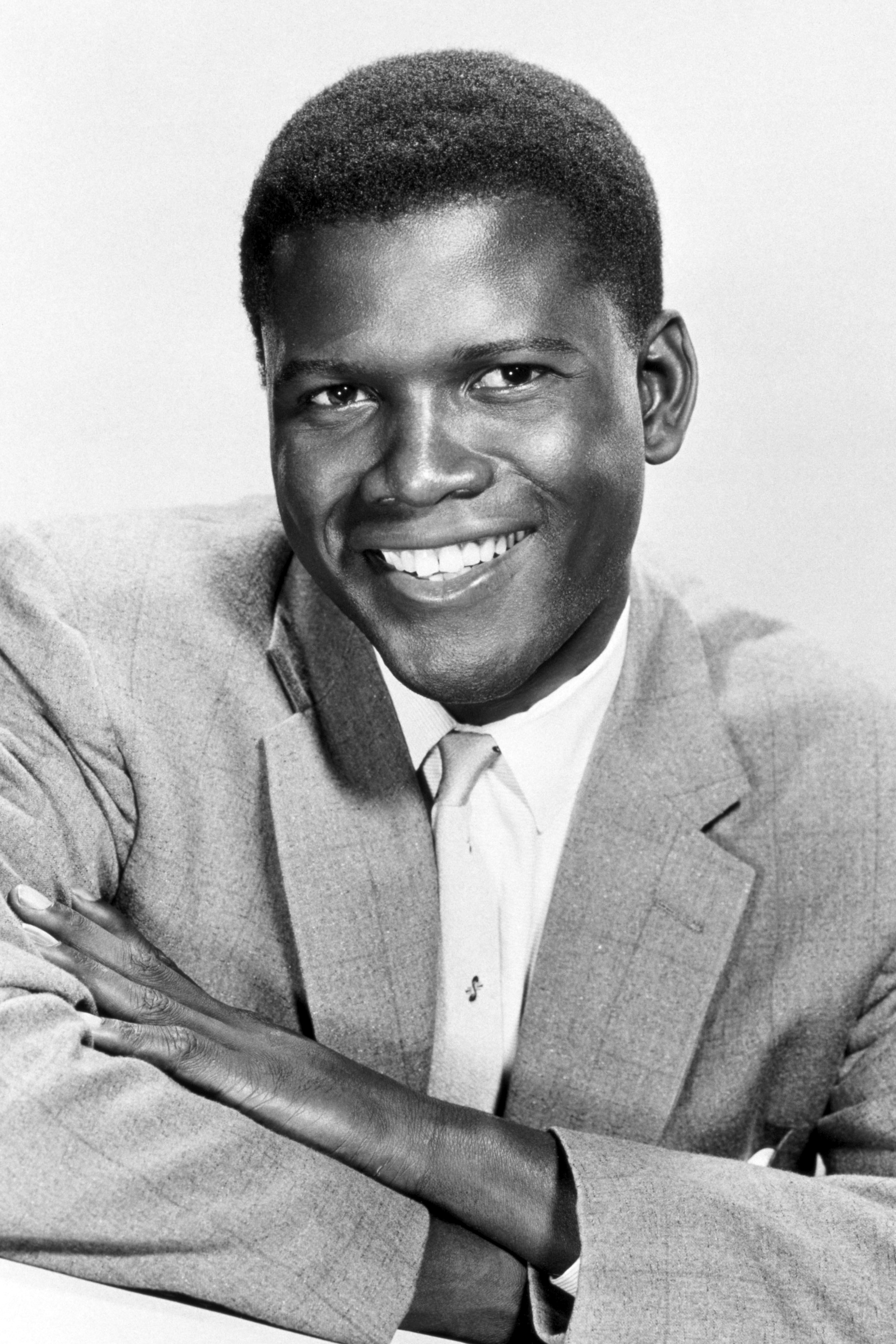

So, she said to me, “I’ll let you understudy the guy who’s gonna play the part.” Now, she had no intentions of me ever, ever playing that part. So I took it. I didn’t know she had no intentions. I just learned that later. The guy that she had chosen to do the part was Harry Belafonte, a very handsome, well-known, good actor. Anyway, long story short, I studied that part, and I was on top of it as best I could. The evening of the performance, Harry Belafonte unfortunately could not come because his father was the janitor at a building, and he had to help his dad take the ashes from the furnace that heated the place. There were 8, 10, 12 big, big baskets of ashes, had to be taken up for the dump trucks to take away. And he had to do it on that particular evening. So she was stuck with me, and she sent me on. I went on, I played the part, I knew all the words. I had my accent, you know, and I did the best I could.

There was a guy in the audience who had directed that play before and had been invited by the lady who directed it. She had asked him to come and take a look to see what she had done with it. And the guy came on a night when Harry Belafonte, the star, wasn’t going to be there. So she put me on.

And this led to your first appearance on Broadway. Was that in Lysistrata?

Sidney Poitier: Lysistrata was my first job on Broadway. Very, very first job on Broadway. That same guy who came and looked, he said to me, he said, “Would you come to my office on Monday?” And he says, “I’m doing a play called Lysistrata…” It was a Greek comedy. I went, and he had me read, and he offered me a job, my first job professionally.

We understand you had stage fright on opening night.

Sidney Poitier: I was petrified. I was petrified. I knew there were 1,200 people out in the audience waiting for me to walk out on that stage. And I only had a very small part, and that was in the very beginning of the of the evening. And on my way to the stage they said “places” which means everybody get ready, curtain’s gonna go up. But I had seen everybody in this play — not everybody, but most of the guys in the play — going to a little peep hole and looking out in the direction of the audience. And I was so interested in what they were looking at. I went and I took a look and I saw 1,200 people sitting, looking at the stage which the curtain hasn’t gone up. And I got so petrified. Then the curtain went up. And the play opened with me running out on the stage and saying, “So and so and so and so and so and so and so.” And they asked me, “Well, wah-dah-dah.” And I say, “Blah blah blah blah.” And then “Wah wah wah.” I got out there, and I couldn’t remember one word!

You ended up getting a good review though, didn’t you?

Sidney Poitier: I got a very good review. I got several splendid reviews, because I got out there, and I mixed up the dialogue. I was so frightened, I was so petrified, that I started it, but instead of starting with my first line, I started with my seventh or eighth line. And the guy who was supposed to answer me, his eyes went BOING! And he said, “Uhh…” And he takes his line, goes back and pulls up the response to this line, and it got all (mixed up). But, the audience is laughing because those who didn’t know the play, thought that that was the play. Well, I messed up the scene. But they — the other actors, because I didn’t come back on the stage anymore after I walked off — the other actors kind of righted the boat for them, and the play went on. Well, the critics said, several of them said, “Who was this kid who walked out there and opened this play? He was full of humor…” and so and so and so…

I left the theater after I came off, saying to myself, “That’s it, I tried, I am not gonna be an actor. I don’t have the gift. And it’s silly for me to be (doing) this. Okay, I did it, I’ve stuck to it, and I don’t have it.” So I left, and I went walking about in New York City. And on my way home, about 11:30, 12 o’clock at night, I’m on my way to my room where I had my residence, I decided to pick up the newspapers, and I picked up, I guess, The Daily News. And there were, believe it or not, there were 13 major newspapers in New York City at that time. Anyway, in three or four of them, I was mentioned very favorably. Well my dear, being — well, being, being, being — I changed my mind. I wasn’t gonna quit the business so quickly!

The last performance — because the show closed in three days, it didn’t get good reviews for itself — a Broadway producer who had on Broadway at that moment a show called Anna Lucasta — he came to see the show that night, the last night. He came backstage and he said to me, he said, “Let me ask you a question.” Now by the way, I’m reading my lines better. He said, “I have a show called Anna Lucasta, and I’m sending out a road company.” He said, “I wonder if you’d like to work for me and be an understudy.” And I said, “Yes, I would like that.” And he hired me. That was my start. I played Anna Lucasta on and off for years and years and years.

Even early in your career, when you were struggling, you turned down roles you didn’t believe in. You actually turned down a part that the agent, Marty Baum, recommended you for. He wanted you to take the role of a janitor in a gambling casino, but you refused.

Sidney Poitier: I did.

Was it because you wanted to portray a more heroic figure?

Sidney Poitier: No. It wasn’t the heroic nature of the character. Let me set the scene for you. I’m married now, my second child is about due. I don’t have any money. I’m working as a dishwasher.

But you had already played leading roles in films…

Sidney Poitier: Yes, yes. But I didn’t go right to the top. It was a bump here and a bump there and difficult times in between. Anyway, Marty Baum didn’t know me but he had heard of me, and he asked me to come to his office, the agency. He sent me next door to a hotel that his office was adjacent to. He said, “These guys are doing this movie, it’s a movie about a place called Phoenix City. And it’s a good part. Would you want to go?” And I said yes. And he sent me over, and there was the director and a writer and the producer. They explained it to me what the thing was, and they gave me a small scene and said, “Would you read this for us?” And I said yes, and I read it for them, and they liked it. And they said, “Okay,” he said, “We’ll talk to your agent.” And they said, “Here, take this script with you and read it when you get home.” So I go back to Marty Baum, the agent who sent me there. I told him what had happened. And he said, “Well, go on. Take it with you, and you read it. And you’ll come back…” He feels that they want me to do it. He said, “And let me know what you think about the script.” I said, “Fine.” I went home, I read it, and I hated it. I really hated it.

It was a story in which there was a janitor. I have no — and had then — no objections to playing a janitor. But this guy in this movie worked for a gambling casino. He was a janitor in this gambling casino. A murder takes place, and the bad guys were concerned about me, the character. If I had seen anything, that would be trouble for them. So what they did to seal my lips — I had a child, the character had a child, little girl. They killed the girl and threw her body on the lawn of his house. And I’m playing this guy.

I went to Marty, and I said — Marty Baum, the agent who put me on to it. — I said, “I read the script, and I can’t play it.” And he said, “Why can’t you play it?” I said, “I can’t play it because this is a father, and he has a child, and these guys kill his child to intimidate him. And the script permits that intimidation. So the writers feel that that’s just for them a plot line. You know? It’s not important to them.” And I said to him, I said, “I can’t play that, because I have a father. And I know that my father would never be like that. He would never under any circumstances be like that.” I said, “As a father, I would never be able to not attack those guys, do something to show how I am, to articulate me as a human being.” And he says, “That’s why you don’t want to do it?” And I said, “That’s why.” He says, “You need money?” And I did. My second daughter was about to be born, and I needed the money. I really needed it, and the money was $750 for playing this part, which was a lot of bucks.

Anyway, I couldn’t do it. Now, that speaks of who I was. It still speaks of who I was. And it speaks of who I am. But who I am is my father’s son. That’s who I am. And I spent my life with him until I left him at the age of 15. And I’ve seen him behave with my mother and their children. And I’ve seen him with my mother, how he treats her. I grew up on that. I know how to be a decent human being. So I couldn’t play it, and I didn’t play it. I left Marty’s office, and I went to 57th Street. Yes, 57th Street and Broadway. There was a loan office there called something-something finance that you could go in and borrow money on your furniture, on your car or whatever. I needed $75 to pay Beth Israel Hospital for the birth of my child. And I had to put up my furniture, such as it was. And they loaned me that money. I paid Beth Israel Hospital, and my baby was born.

Anyway, some months later, Martin Baum, the agent, called me up and he said, “What are you doing?” I said, “I’m working in this restaurant.” He said, “What do you do?” I says, “I’m washing dishes.” But I had a little bit of an investment. And he said, “Could you come down and talk to me? I want to ask you a couple questions.” I said, “Sure.” I went down, I walked in, he’s there alone, I sat down with him. And he said, “I have never been able to understand why you turned down that job for $700.” Eventually I would tell him why. I don’t know whether he understood it or not. But I think before I told him, he said to me, “I have decided that anyone as crazy as you are,” he said, “I want to be their agent.”

And how long did he remain your agent?

Sidney Poitier: ‘Till now as we sit here.

Someone else who was an influence on your career was Lloyd Richards. Could you tell us about him?

Sidney Poitier: Lloyd Richards was the director of A Raisin in the Sun. And he was more than a director. He was a theater master, master of theater. African American, extremely gifted. He and a man named Paul Mann, they were teachers. They had a teaching — a drama school, actually. And after I did the picture Blackboard Jungle, I went to see them because I knew I wasn’t working at the level I should be working at.

Even though that was a very successful film.

Sidney Poitier: It was a successful film, and I did fairly well, but the part was not fulfilled as much as I could have fulfilled it. So I went there and I asked them if I could come and take some classes, and they said yes. They invited me in. I stayed there for a very long time. And they taught me. I learned so much. I learned from them that behind words are meanings. Every word has a meaning, and its meaning might simply be used as a connection: is, as, was, then, now, last, first. There’s a meaning. Now, when we put words together, if we don’t express what the meaning is behind this particular bunch of words as actors, if we cannot articulate what is behind this bunch of words — which would be maybe just one paragraph — behind it may be one point of view or it may be a combination of points of views. The audience hearing these would expect to see them exemplified in the behavior of the actor. They taught me how to do that.

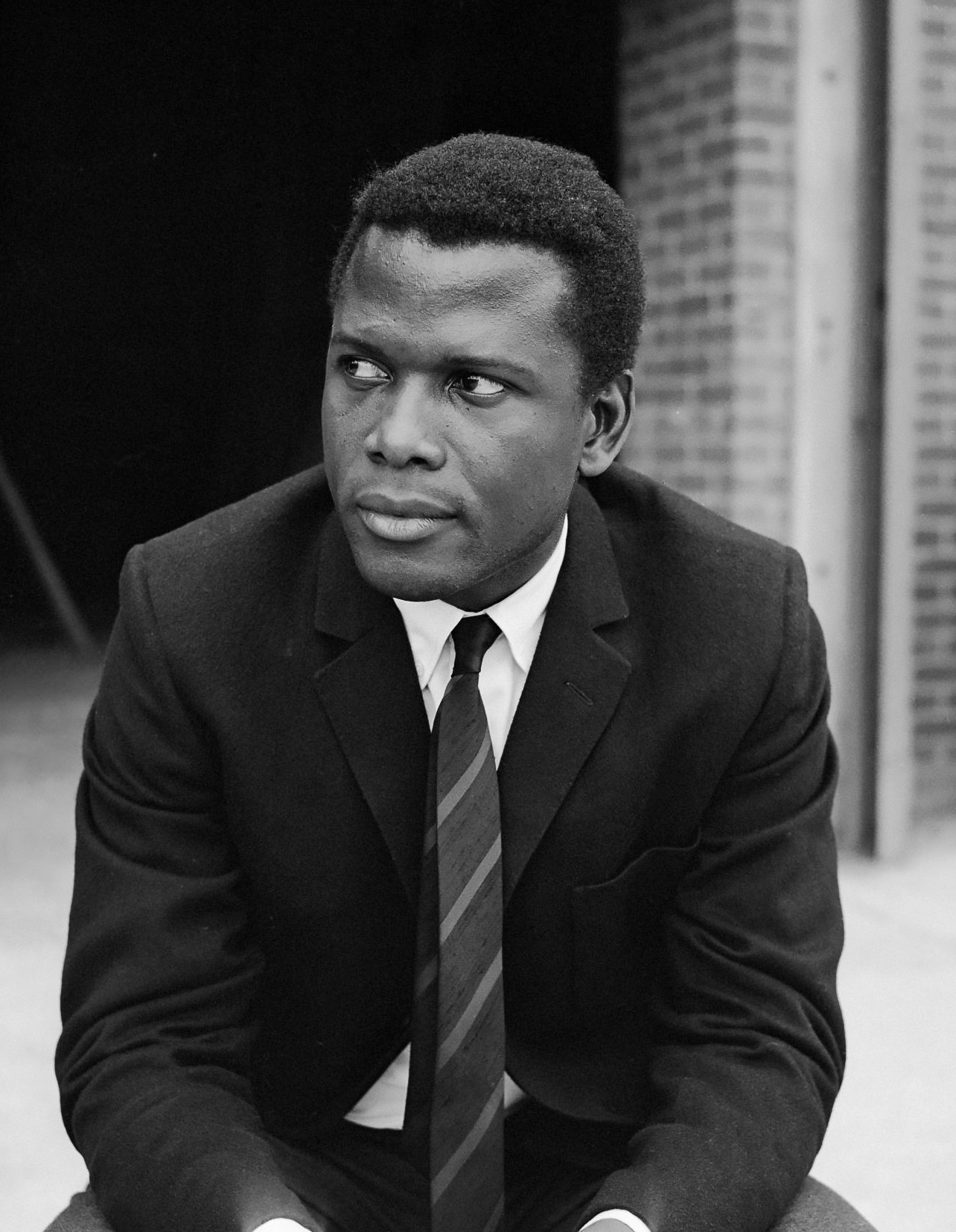

The Defiant Ones was a big step in your career, and you were nominated for an Oscar. You spent most of that film chained to Tony Curtis.

Sidney Poitier: It was a wonderful experience for me because it was produced and directed by a great filmmaker named Stanley Kramer. And I had a chance to work with Tony Curtis, and we got along wonderfully well. The only thing that is really outstanding is that it was a production of Stanley Kramer. He was one of Hollywood’s most liberal, most courageous men in the business, particularly during a delicate time in America. Working for him was pleasure, a total pleasure.

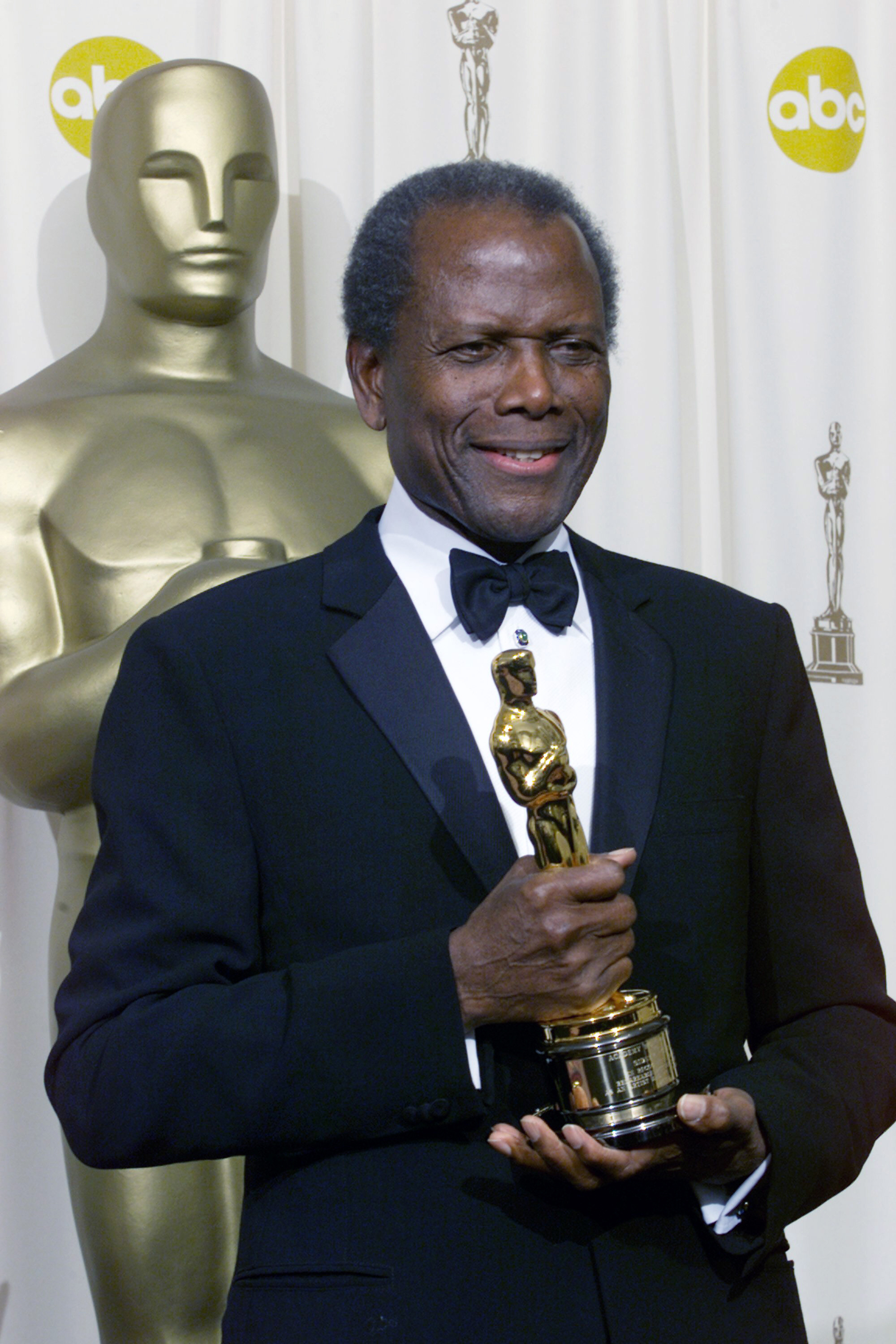

Lilies of the Field brought you the first Oscar for Best Actor ever awarded to an African American. That was historic. Can you talk a little about that role and what it meant to you to win that Oscar?

It was pretty much how I am. And what it meant to me to receive the award for it, it meant a great deal to me. It was the first time for an African American. I thoroughly, thoroughly enjoyed the experience, because what he was doing — the character mind you — what he was doing was exhibiting a vast sense of himself, and the wonders of being alive, and the wonders of being a human being, and the responsibilities of a human being. And here he is vortexing with some of the most loveable characters. And for that I got an award.

I embraced the award. It was wonderful. The man who wanted so badly to make that movie, did in fact, direct it. Ralph Nelson. I’ve made movies for him in my career several times, three times, as a matter of fact. Ralph Nelson was a very, very, very humane person. He hired me for three fantastic roles. I will always be indebted to Ralph Nelson because he was a real humanitarian.

In your film In The Heat of the Night, there’s a scene that is very famous. That’s the scene where you are slapped by this wealthy, white businessman. At first, that scene was written differently. Why did you need that scene to change?

Sidney Poitier: Well, the producers were all whites. I was one of the principal players in the movie. I know what my values were. My values are not disconnected from the values of the black community, the African American community. So I go in front of a camera with a responsibility to be at least respectful of certain values. This other character was a very wealthy, very well-positioned person in this community in the South.

And he’s under some suspicion at this point in a murder case.

Sidney Poitier: Correct. And I am a detective out of Philadelphia. I’m on my way home after having visited my mother. The producer happens to be a very close friend of mine, Walter Mirisch. When I read the script I said, “Walter, I can’t play this.”

The scene required me to stand there, this guy walks over to me, and he slaps me in the face. And I look at him fiercely and walk away. And I said to Walter, I said, “You can’t do that.” I said, “Let me tell you a little bit about America and the texture of American culture as it stands.” I said, “That is dumb. It is not very bright.” I said — we’re in the ’60s, this is 1968 or 7 — “You can’t do that.” I said, “The black community will look at that and say that is egregious. You can’t do that, because the human responses that would be natural in that circumstance, we are suppressing them to serve values of greed on the part of Hollywood, acquiescence on the part of people culturally who would accept that as the proper approach.” I said, “You can’t do it.” I said, “You certainly won’t do it with me.”

I talked to him about it. I say, “Therefore, if you want me to do this, not only will I not do it, but I will insist that I respond to this man precisely as a human being would ordinarily respond to this man. And he pops me, and I’ll pop him right back.” And I said, “If you want me to play it, you will put that in writing. And in writing you will also say that if this picture plays the South, that that scene is never, ever removed.” And Walter being the kind of guy that he was, he said, “Yeah,” he said, “I promise you that, and I’ll give it to you in writing.” I ultimately didn’t take it in writing. I just took a handshake because he’s the kind of guy, his handshake and his signature is one and the same. And that made the movie. Without it, the movie would not have done as well as it did.

We’d like to go back to the very beginning now. You’ve written about the unusual circumstance of your birth. You were not expected to survive. Can you tell us about that?

Sidney Poitier: My birth was quite unusual in that I was premature. I wasn’t expected to live. I was delivered by a midwife in Miami, Florida, in the African American section of that city. And there were no available hospitals for people of African descent. So certainly my mother didn’t know of one.

So I was born in a small house that was not ours. It was a house that my parents would live in because my parents were not Americans. My parents were Bahamians, which is a group of islands off the coast of Florida. Many, many, many islands. They run into the hundreds. Some of them are just that big (tiny), but many of them were large enough for populations to gather.

My parents were tomato farmers. They farmed tomatoes and they sold their tomatoes in Miami, Florida. They went two, sometimes three times per year. They would harvest, and they had to harvest at a given time, because there were no motorboats that would take their stuff across. So they had to go by sailboat. So they reaped the harvest prematurely. They had to, in order for it to ripen on the way so that when they got to Florida the fruit would be ready for sale. And on one such trip, my mother was pregnant by some six, seven months. They had no expectations that I would be born in Florida. But her water broke, that’s a phrase, I guess, that you would understand. The water broke, meaning that, of course, something happened in her internal structure that the baby was gonna come whether it was nine months or not. So it was that I was born in Florida unexpectedly.

They had to keep me there for some three months, because I was so underprepared for birth that it took three months for me to hit a point at which they could take me on a sailboat, which would take several days back to the Bahamas and their tomato field.

During the period when I was really, really close to not being here, everyone gave up on me. The midwife gave up on me. My father also gave up on me because they had had many children. I was the last of the lot. And my dad felt that having experienced births before in his family, he had no confidence in my surviving, because what had appeared to him was that this child was too fragile to survive. And my mother had a different point of view. My mother would not accept that. She did not accept it. As a matter of fact, the evening I was born, the very next morning, everyone present — but meaning the local people who were friendly with my parents, and the people who were not, they saw the child. Me. And they said, “No chance.” My mother had a different point of view.

Didn’t your father actually find a little coffin for you?

Sidney Poitier: He did. He left the house the following morning, and he went for a stroll. And that stroll ended up at the local undertaker’s parlor, in a discussion centered around preparations for my burial. And he came back to the house with this little shoe box. It was, in fact, a shoe box. And he came into the house with it. And my mother, who was naturally prone in bed, she was so outraged that she got up and she dressed herself — against everyone gathered there — and she left the house. She went out into the world, I suppose, figuratively speaking.

Anyway, long story short, she went out, and she spent the whole day, I suppose, going to local churches. Wherever she could find help, she would go. But the day ended, and there was nothing. So she’s on her way home.

She decided to stop in and visit a soothsayer. You know what they are. They are fortune tellers in a peculiar sort of way. And she stopped in and she said to this lady who was there, she said that “I just gave birth to a son.” And she explained what the circumstances were and stuff like that. And she said, “I want you to tell me about my son.” And they sat down, and this lady began. First she went into — I hate to say it, but this was the way I get the story, she went into a kind — she closed her eyes. The soothsayer closed her eyes, and she began to talk in a strange language. No language at all, I guess. It was gibberish to anyone listening, but my mother was hearing her. And then suddenly the soothsayer’s eyes flew open, and she looked at my mother and she said, “Don’t worry about your son. He will survive, and he will not be a sickly child. You must not worry about that child.” My mother came back to the house. It cost her 50 cents. In those days that was a lot of bucks. She went back to the house, and she told my dad to remove the shoe box from the house. “There’ll be no need for it,” she said.

Didn’t the soothsayer also predict that you would walk with kings?

Sidney Poitier: Yes, she did. She told my mother that I would travel to all the corners of the earth, I will walk with kings, I will be rich and famous. I don’t know about that, but she said so. Everything that she said to my mom, it’s amazing, everything came true. I have not to this day figured it out. I’m 82-years-old, come this Friday, but I could really never figure it out. I have a sense of practicality. I believe in logic and reason, two tools that I can apply, and somehow figure it out using those two elements. It’s not that I am stubborn. I am in some areas of my life, but it wasn’t that I was stubborn. I just felt there was something about that circumstance, that if I look at it logically and then put into it all kinds of other elements like my mother’s faith, for instance, that I could at least accept it as a part of the unfolding of this life of mine. So I’ve spent my life trying to understand it — not in terms of its component elements, but the whole occurrence — in terms of those forces in nature that have influences on our lives. Many people perceive it as strange, unusual, miraculous, all kinds of ways. I still don’t have a fix on it, but I do believe that there are forces in nature that we don’t understand, and probably never will, that have an influence on our lives that defies understanding.

You were very close to nature as a child on Cat Island, weren’t you? You’ve described it as an Eden.

Sidney Poitier: Yes, it was. But that’s in retrospect. I hadn’t seen the rest of the world. It wasn’t until I saw the rest of the world that I grew to understand that it was a very, very interesting setting.

What was life like on Cat Island? You didn’t have a lot of modern conveniences.

Sidney Poitier: No, we didn’t. We didn’t have any electricity. We had no roads. We had roads, but they were pathways in a way. We had very little. I mean, we ate from the sea, food from the sea, and what they grew in their subsistence farming, in a particular way. Their main crop had to be tomatoes, ’cause that’s how they made their living, and that money was spent in Florida, some of it, some of it in the capital, on the capital island which was Nassau. And they would bring certain hard groceries with them, mostly from Nassau. And hard groceries, I mean canned goods. There would be canned milk that would be shipped into the Bahamas from England. And there would be salt pork and salt beef and lard. We ate a lot of lard. There was no such thing as olive oil and all the good stuff, you know. We used lard to cook with. And we ate from the land and the sea.

No cars?

Sidney Poitier: Oh, no. I didn’t see a car until I was ten-and-a-half years old. And when I did see a car, whoa! I was on the boat with my mother, a sailboat, going into Nassau harbor. This is the first time I’m leaving Cat Island.

The state of Florida was encouraged — that’s the proper word, I think, was encouraged — by tomato farmers in Florida to stop importing tomatoes from the Bahamas and I suspect from other areas in the Caribbean. And it fell like that, whatever body was making the determination. And my father’s business just went, “Phew!” There was no place else to sell the tomatoes. So that’s all he’d ever done in his adult life. So he had to go and take the family to Nassau, which was a tourist island, and he would have to find a way to support his family by working there, doing whatever he could find, because he didn’t have very much money. He barely had enough to move the family to Nassau where he would look for a job.

Is that where you saw your first car?

Sidney Poitier: My first car. I’m coming in on a boat, and I’m just wild-eyed as I see the island coming up. It looks like a regular island at first, but it’s the first island I’m seeing other than the one I grew up on.

So I’m looking at this place, and then I saw what appeared to me to be a beetle, but it was massive. It was huge. And, I was fascinated looking at this thing. We are still quite a distance from Nassau. But there were obviously these beetle things. I said to my mother, I said, “What’s that?” And she said, “That’s a car,” because she had seen them in Miami and in Nassau before. And I said, “A car?” And I said, “What is that? What does it do?” And she tried her best to explain it to me until, of course, we got to the docks and I got off and I saw this thing up close, you know, and I was fascinated. I wondered, “How does it move? What is making it move?” It was just amazing. But so were so many other things, amazing for me, for a long time on Nassau, because there were windows. There were paved roads. Never seen a paved road. There were windows along the streets on the main thoroughfare which was near the docks. And there was glass. But it was glass you could look through, like you can look through a glass bottle. And there were many things in the window. There were goods and stuff in the window. And I couldn’t understand it. I didn’t know what glass was.

Had you ever seen a mirror?

Sidney Poitier: I hadn’t seen me in a mirror, of course not. There were no such things on Cat Island. I had seen my reflection in the pond, because my mother used to go to wash her clothing and the rest of the family’s clothing in a pond in the woods. It wasn’t really a forest, because the trees were never that tall. They were six, seven, eight feet tall. Not much taller than I was. She would take me with her when she did her laundry. She would add a little Octagon soap to a garment, and then she would beat the garment on a stone. That would get the dirt out of it. That’s how she did her washing.

So you had seen yourself in the pond but never in a mirror.

Sidney Poitier: Never in a mirror. I didn’t really see myself in the pond, because you can’t see yourself in a pond. She’s washing our clothing in the pond. With every movement, wherever she touches the water, it ripples. If the wind is ever so slight, there’s a ripple. So you can’t make out anything.

I didn’t know what a shadow was. You ready for this? I saw my own shadow, and I didn’t understand it. Mind you, I’m a kid. I’m a little, little kid. Eventually, my shadow became my best friend because it imitated me. Every time I do that, every time I do that, I could see my shadow doing the same thing. So my shadow became my friend. I used to race my shadow down the beaches, and depending on where the sun was, I would win sometimes, and my shadow would win sometimes. Oh my God. I’m glad psychiatry wasn’t around then. They probably would have put me away.

Where did you start school? Was it in Nassau?

Sidney Poitier: No, I was in school on Cat Island. On Cat Island, there was a school house. The school house was a “multiple,” meaning that there was one room. And the children, I don’t think there were more than grade one to three, maybe four. And I went on Sundays. Other days I went to the farm. I was going to the farm to work at five years old. Not every day, certain days I went to the farm. When there were available days for the school, I went to the school house.

Do you remember when you saw your first movie?

Sidney Poitier: When I saw my first movie, we had moved to Nassau by then, and we left Cat Island when I was ten-and-a-half. I was like a kid coming out of the center of the United States from the smallest, tiniest farming area and suddenly put into New York City. That’s the kind of impact, going into this whole new culture in Nassau. My folks were able to rent a small house, again, with no electricity and no running water and all that stuff. Anyway, this little house had to accommodate us all, and there were five boys and two girls in the family. I think the eldest of the group had already separated and were out on their own when we got to Nassau. They could start working and assuming responsibilities for themselves over and above the farm that we ran.

But anyway, I made some friends quite quickly. I met these new kids who were in this particular neighborhood, and they sort of embraced me. And they said to me — oh, I guess some weeks after we had moved — they said that they were going to a matinee, would I like to come? And I didn’t want them to know that I didn’t know what the word matinee meant. So I said, “Okay, sure.” I want to be one of the group. So they went to this theater. And this place had a façade that had pictures of people, white people, on the outside, which ultimately I came to understand were advertisements letting the audience know what the movie is about.

But, I didn’t know I was going to see a movie. I had no idea. So they bought a ticket for me, and we went in and we sat. And in this place there were many seats. Well, the whole place was seats. And we took a row there, and we’re sitting there. And I am making sure that I don’t slip up and ask the wrong question or something, because I know that I would make a fool of myself. So I just behaved as best I could as one of the guys, you see. Anyway, the lights go down, and a curtain, big curtain thing opened up. And there was this big white frame. And suddenly, out of nowhere, came letters, big letters, words, on this big, white screen. I can barely read. I am not really a reader. I read terribly. So I couldn’t make out really what the words were saying, except some of them were names, and you assume that they were names. So I just kind of waited to see what’s gonna happen with this lit up screen. I didn’t know there was a word called screen. But then I saw people, and it shocked me. How did they get there? Then I saw cows and I saw wagons and I saw brown people wearing skins and feathers. I had no idea. I would learn later that there were Indians and there were white people, settlers, in certain parts. That was my first movie.

Did you want to look behind the theater to see where they were coming from?

Sidney Poitier: Yeah, well that’s when it’s done. The movie is over. I am not about to make a fool of myself to my friends, yeah, I understand. I can’t talk to them. I can’t join the conversation as they’re talking about what the cowboys did and what the Indians did and what the people in the town did and so many horses and cows and stuff. So I kind of kept quiet. But as we started home, hmm, I said, “Listen guys, I’m gonna peel off for a little bit, and I’ll see you back at the corner.” So I kind of like dallied a bit, and then I turned around and I went back. I went to the back of the theater, because I didn’t understand how all those cows and the people and — how did they get the houses in that little building where I was? How could all of that happen? I had no idea. In the back of the theater was a door, just a door. It was too tiny for all those cows to come through. I didn’t understand, but I thought that something was going to come out of there. They have to. But nothing came out.

You were quite young when you started working, to help support the family.

Sidney Poitier: Twelve. A year-and-a-half from the time I arrived in Nassau from Cat Island. I went to a school there in Nassau, but I wasn’t very successful at that. Then the fragility of my parents’ economic situation forced me to go to work.

I was 12-and-a-half. I was tall. I figured I could get a job, because it was really wearing my dad out, you know. So I quit school and went to work. First I went to work as a water boy, working on a construction thing. I would go around with a dipper and a bucket, and these guys were all working in the sun, you know. In that part of the world the sun is fierce. So I walked up and down the line where these guys were working, and I have this bucket and this dipper and they would take a drink and so that was my job. But it didn’t pay very much, and my folks really were in need, so I decided that I was tall enough to hike my age and maybe get a job as an adult.

I went to the assistant to the foreman. He knew of my family, and I suspect he chose to make an exception, ’cause he knew what was going on. And he moved me, he gave me a pick and a shovel. I was among the big guys, and I was using a pick axe and shoveling dirt up out of this ditch, up onto the region up above it. And because the pay was much, much better in the aggregate — or rather the difference was such that — it was very helpful for food and all that stuff. I was making today’s equivalent of maybe two dollars, three dollars a week. But in those days the three dollars went quite a ways.

I stayed at that job, and then I worked as a delivery boy, and then I worked in a warehouse. Because I was tall, they just assumed I was eligible. I would have to take 98-pound bags of rice or sugar or flour and stack them to the ceiling of this warehouse in town. We would lay the foundation for it. Every bag of whatever would be put here until it covers the whole floor. And then we’ll use each bag as a step. And then we’ll do another, and then another step, so that toward the end, I would have 98 pounds on my shoulder, walking up these steps to the ceiling. And because we can’t go beyond the ceiling, I put this as the last up there. I stayed on the job quite awhile and I developed — ladies develop it when they become pregnant — varicose veins.

How did you or your family make the decision to send you to Miami?

Sidney Poitier: I hit a bad spot wherein I couldn’t find another job. My father became concerned. I had a friend, his name was Yorick Rolle. Very close, my very best friend at that time, we were like that. We used to buy raw peanuts, if we had a couple of pennies. We would buy raw peanuts and we would roast them, put them in little teeny bags and go to stand in front of the theater and sell them to people going in. But we were doing that just to make enough money for us to buy a ticket ourselves and go in to see the movies. Anyway, he was without me one day, we were that close all the time. And for what reasons, I don’t know, but he — on that day, I was not with him — and he stole a bicycle and he was caught, and he was sent to reform school for four years.

That worried my dad, because he knew I was very close with this guy, and he knew his own life was in the process of deterioration. He was in his 50s, I would think, and the wear and tear of all his experiences with farming had weakened his back. And finding jobs was difficult. So, he is not a young man anymore, anyway. He began to be concerned about me. I was leaving the house one day and he stopped me. He was sitting at the door of this house that we lived in. And as I stepped out of the door on my way out, I looked at him and he looked at me. And he said to me, he felt my arm, and he said, “You’ve not been eating regularly, have you, son?” And I said to him, “Oh I’m okay, I’m fine,” I said, “I’m fine.” I knew the weight that brought that out of him.

My oldest brother had stowed away on a motorboat that ran between Nassau and Florida. He was the oldest of the boys. He had stowed away. He went to Florida and he got away with it. He found a job and he worked very hard. Tremendous guy, this guy was. Cyril was his name. He met a girl, fell in love with her and she with him and they got married and he went down to the police station in the center of Miami and he told them that he was a stowaway and that he has been here such and such a time and he explained to them what he did. That he works, and he has always worked, and he gave them the name of the employers and all that, and he said he wanted them to know that. And he said, “I have children.” Anyway, they allowed him to stay. I don’t know what the circumstances were, but they allowed him to stay, and I was sent to him.

You didn’t like Miami much. Could you tell us about being a delivery boy in Miami and the experience you had there?

Sidney Poitier: I was a delivery boy. I worked for a place called Burdine’s department store. My brother worked there and I got the job through him. Yes, I hated Florida. At least I hated Miami, I didn’t know Florida. I suspect that I would have hated Florida if I had traveled about in Florida, because Miami was no different from the rest of Florida, but I did hate it. I hated it because it was an unfair place. For instance…

I was told to deliver a package to Miami Beach, this is from Miami itself. You go across the causeway, or you just walk across, or you take the bicycle — they had a bicycle for the delivery boys. They gave me the address and they explained to me how to get there and I went and I found it. And I went to the place, I saw the address, and I matched it with the thing they had written for me, and I went up to the door and I either knocked or pushed a button. A lady came to the door, a white lady. And she said, “Yes?” And I said, “Ma’am this is your package. I come from Burdine’s department store.” She looked at me in the most amazing way and she said, “Get around to the back.” And I didn’t understand, I really didn’t understand it, because she’s standing right there. She obviously is the mistress of the house, and I’m standing within three feet of her, and this is a big house. And I said to myself, “Why do I have to take it around the back? It’s a small package.” Were it something that’s too weighty for her, certainly I’ll carry it a mile if that’s the case. But I wasn’t aware of the depth of racism. I had been experiencing it every day there, but the impact of it in such a coarse way! She slammed the door in my face. And I took the package and I set it right down on the step in front of the house and I left.

I go back to Burdine’s Department Store and I did whatever my duties were. When the day was done, I went to Liberty City, which is where I lived. My brother lived there, I was living with him. I had a few pennies, and I decided to go to a movie, and at the end of the movie…

Now, I’m going home to my brother’s house. And I approached the house and there are no lights on. Well, I jiggled the lock — I mean the doorknob — it’s nothing. And then the door suddenly opens and it’s my sister-in-law — my brother’s wife — and she grabs me and pulls me into the house, slams the door, and on the floor she’s lying with her children. And she pulls me down and she said, “What did you do today?” I said, “What did I do? What do you mean?” She explained to me that the Klan had come to the house looking for me, because I had misbehaved I guess.

Weren’t you frightened?

Sidney Poitier: I was not frightened. I wasn’t as frightened as one might assume. If I knew that the Klan would be there, I would have been — if not frightened — I would have been at least on my guard. Now mind you, I am 15 going on 16 now. I’ve been in Miami just a few months. I went to Miami from Nassau and I went to Nassau from Cat Island and between Cat Island and Nassau, my perception of myself had already taken hold.

I didn’t spend the first 15 years of my life cringing in the presence of white people. The overwhelming — and we’ll get to this as well — the overwhelming majority of people in the Bahamas were black people. So I grew up those 15 years — with the exception of the three months when I was a baby in Florida — I spent them in Cat Island and Nassau. And spending them on Cat Island and Nassau, I was within the circumference of the black community constantly. So that I saw people, how they behaved with each other. I saw respect for each other, I saw laughter, I saw an embrace, I saw it was an environment that nurtured me in ways that I wasn’t even aware of, so that I got to 15 not afraid of white people.

You already had a strong sense of your own worth.

Sidney Poitier: But that strong sense of self-worth came from the Bahamas itself, out of my family, out of the families I knew. Out of the society, such as it was. But they treated each other respectfully, they raised their children to be respectful of elders. If my mother was unable to work in the fields, her friends would come by and bring food. It was a wonderful community. When we got to Nassau, it was somewhat different, but still…

Ninety percent of the people in Nassau were black. The cops were black. All the policemen were black, except possibly the head of the police department and his lieutenants. Mind you, I’m talking about a colonial country, but because it is a colonial country — and luckily for us, the colonial country being Great Britain — they could not manage a colonial empire, because they were so few people. The British were very few. Do you know that, literally speaking, a very small number of Britons ruled India? They ruled most of the Caribbean, and they could not — there was no way for them to cultivate the necessary personnel they would need to administer to their colonial possessions. So what they had to do, they had to educate the local people, so that there were policemen. All of the policemen, with the exception of the few guys who ran the police force, were black. So as a kid I didn’t run around being fearful that I was going to be mistreated. Okay, that gives you an idea of what I came out of, and the values I came out of the Bahamas with when I went to Miami.

I walked into the police station to get permission to go across the street, which was a vital statistics department of the government. I was going over there to get a birth certificate, because I had misplaced my birth certificate, which I had gotten from the U.S. Embassy in the Bahamas. I walked into the police station, and I said to the gentleman, I said, “Sir…” and I called everybody “sir” because my father taught me that, and my mom. Pow, pow, pow! “You say ‘sir’ to your elders.” Anyway, I was respectful.

I walked into the police station to get permission to go across the street and so and so. And he called me the “n” word, the guy in the thing, and he said, “Take off that hat.” I was wearing a cap. I looked at this guy sitting up on a kind of thing at the desk. And I said, “What’d you call me?” And mind you, I’m a kid of 15 years old. I just lost it. I just said, “I am Reggie Poitier’s…” that’s my father’s name, “That’s my dad, and his name is Reginald and my mother’s name is so and so. And they named me Sidney, that’s my name.” Well, the cops, there were several in the place, and they looked at me as if I was insane. Oh God! Now, had I been born and raised in Florida, I would have a different approach, exactly. I would have been cultivated to respond in a different way, especially if I had spent those first 15 years of my life in Florida.

Not long after that, you went to New York City, on your own, with just a few dollars in your pocket. A very brave adventure. What was that like?

Sidney Poitier: Well, I got to New York by hopping freight trains and all kinds of different, interesting ways. I wound up in Georgia first. I didn’t get to New York. I wound up in Georgia in the mountains working as a dishwasher in a summer resort. I accepted the job as a dishwasher in Georgia. I took a bus from Florida, and I went to Atlanta. They transferred me to another bus that went to another place, close to the foot of the mountains, and someone met me there and took me up the mountain. And I spent my time washing dishes there. I saved all of my money. I never took a dime. I spent much of that summer there, all within the same year. And I came down from the mountains, and I went to the bus station, because that’s how I got to the mountains. And when I left there, I had $39.

By the time I got to New York, someone had rifled my little bag and taken my money, and I got into New York with very few dollars in my pocket. New York was an experience. It was a staggering experience. It was massive. It was huge. There were incredibly tall buildings. I got there in the afternoon, and the place I wanted to go to was Harlem, to see Harlem. I had heard a great deal about Harlem.

I asked a chap at the doorway of the bus station. I said, “How do I get to Harlem?” I had a very little, small bag with a couple of — three pairs of pants, some shirts, and that’s about the size of it. Maybe one jacket, but not for winter. We’ll get to that. So he said, “Well, you go right down those steps, and you just go to 116th Street.” And I said, “Okay.” So I go down the steps, and I said, “What I do?” when I got down there. And I watched people. They would come and they would put something in the little thing for the turnstile. And the guy upstairs had said to me, “Then you’ll take the train.” And I said to myself, “Wait a minute. Train? Under the ground? That doesn’t make any sense.” And it certainly didn’t make any sense to me. A train under the ground? But anyway, I went through the ritual and I hear this rumbling, and it scared me. And along comes this train. And I saw people putting a nickel — and in those days it was a nickel or something — in and they’d go through the turnstile. Well, I was always courageous in a way, some ways. And I go through the turnstile and I got, as he told me — 116th Street. So I got on the train. And every time it stopped, I was amazed. How could it be running under the ground? Makes no sense to me. But I’m alert, and I’m sitting there. And I see the station comes up, 116th Street. And I jumped off, and I walked and followed people going up the steps. And I walked out at 116th Street and 8th Avenue, and I was in Harlem.

You are largely a self-taught person, and yet you’re probably one of the most erudite, intellectual people in your field. Reading your books is a fascinating and rich experience. How did you come to be so learned without a lot of school?

Sidney Poitier: I don’t know that I’m that learned. I did learn early that everything I want to do in life requires that I accumulate understanding, knowledge, know-how. What is the quickest, most dimensional way to make that kind of accumulation? You have to read. You have to read. I’ve always felt that I didn’t know so much, and yet everything pretty much that I didn’t know is available somewhere. The first place I went to was to newspapers.

I had an experience with a Jewish waiter. I was a dishwasher, and he was a waiter in Queens, New York. I used to buy the local newspapers. Sometimes the Journal American, sometimes The New York Times, Daily News. At the end of the evening, when the waiters are done and the place is closed, just about closing, the waiters would sit at a table, and they would have tea, coffee, or a late snack which was permissible by the owner.

I would sit in the dining room next door to the kitchen. And I would sit there because everything else is done, all the dishes were done except those that the waiters are using for their snacks, you see. So I sit there. And I’m reading one of the papers. And there was a Jewish waiter sitting at the table, elderly man, and he saw me there. He got up, and he walked over, and he stood by the table that’s next to the kitchen, and he said, “Hi.” And I looked up, and I said, “Hi.” He said, “What’s new in the papers?” And I said to him, “I can’t tell you what’s new in the papers because I don’t read very well. I didn’t have very much of an education. So I can’t tell you what’s…” He said, “Ah,” he said, “Well, would you like me to read with you?” And I accepted. I said, “Sure. I’d like that.” Every night after that, he would come over and sit with me, and he would teach me about what a comma is and why it exists, what periods are, what colons are, what dashes are. He would teach me that there are syllables, and how to differentiate them in a single word, and consequently learn how to pronounce them. Every night.

What a great gift.

Sidney Poitier: Oh yeah. I went on to be a very successful actor, and one day I tried to find him, but it was too late. One of my great regrets in life is that I never had the opportunity to really thank him.

You describe in your autobiography a sense of coming alive that you felt, as an actor, fairly early on, that the art of acting kind of electrified you. Can you talk about that?

Sidney Poitier: There is something that takes place in me, but it didn’t always. It wasn’t there in the beginning. What was there at the beginning, in my first experience in front of a camera, my first experiences on stage, was a totally dimensional awareness of life.

I hit the age of 15 not being afraid. I was on my own in New York City at the age of 15. I was respectful to people. As my father explained to me, to elders you say “sir” if it is a man. To elders you say “ma’am” if it is a woman. You respect older people. I learned from him a certain way of behavior. But what I learned was not in terms of something I got out of a book. What I learned was an internal connectedness to life, in the family, in the small community where we lived, how people treated each other, particularly how my father treated his friends and my mother, you see. So I came at 15 to Miami, Florida with a sense of that humanity. That is why I am sitting in this chair now. All of what I feel about life, I had to find a way in my work to be faithful to it, to be respectful of it. I couldn’t and still can’t play a scene, I cannot play a scene that I don’t find the texture of humanity in the material. I can’t.

You also connected with humanity very deeply, which is part of what made you a fine actor and director.

Sidney Poitier: I don’t know how fine an actor or director I am or have been. But every person who goes into a theater — and anyone who watches this video who is interested in theater or the creative arts — anyone interested in theater arts, they enter a movie house, or they enter a theater with a stage, they sit there with other people, it’s a darkened room. Their attention is on what’s going on up there. They have five senses that are the tools they bring into the theater. They know, feel, touch. They know what they see objectively. They know what they hear. So their five senses are working, and they’ve been working pretty much since they were tots. So everything that happens on that stage, everything that happens on that screen, they can pass a judgment subconsciously as to whether we are hitting the marks or not.

There isn’t a person that sits in a movie house, of any maturity, who hasn’t been disappointed, who hasn’t been exhilarated, who hasn’t felt fear, who hasn’t felt joy. Every one of the emotions that human beings experience, even the most terrifying ones, they have been akin to all of them at one time or another, either in their daily lives, their weekly lives, their monthly lives, their yearly lives. So that when they sit in that theater, that’s all they bring in. That’s the scoreboard they bring in. And they sit there and they watch actors playing at fear, embarrassment, at love, at hate, at all of the emotions in life. That’s what they bring in. So when they sit there, and they’re looking at actors doing that, they cotton to those actors that make that connection, makes that connection with them. And that’s the actor’s job, it’s not their job. All they do is they bring this panel of human emotions with them. And these emotions are in neutral. They are absolutely in neutral as they sit there. And one by one, this really fine actress or actor begins to do things that somewhere in the consciousness of that audience, they’re saying, “Ooh boy, yeah, I know about that. I’ve seen that. Wow.” That’s where the admiration comes from, because they can also tell when that actor or that actress is not reaching home.

Just a few nights ago, you received the Lincoln Medal at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, with President Obama attending. What was that like for you?

Sidney Poitier: I was overjoyed, for obvious reasons. It was an evening that I never thought would come in my lifetime. I’m glad it did, because I could use that as a peg around which I can articulate my appreciation of my country — that he became the man that he is as a result of his experiences in this culture. He was an unknown young student with a point of view, with an integrity, with a vision, with an understanding far deeper and far wider than his objective imagery would imply. Objective: meaning his color. He is a young man who perceives himself to be African American. However articulate he might be, he is not only articulate. However visionary he might be, he’s not only articulate and visionary. You can go down the line, and he kept expressing that, showing that to us. Not intentionally, but we just couldn’t help but see it. We saw it. And if you take him back to a time when he was not quite as revered as he is now, and you looked at him then and say that this guy could be president in five years, you wouldn’t get one bet on that. But he has shown us that our survival is totally dependent on us perceiving ourselves as a single family.

We are 6,500,000,000 in our family. We have one home. It’s a planet. It’s a planet that has not grown one single inch since its creation. What is there is what we have. And that is our home. It will be our home until we either self-destruct or until nature decides that it wants — or she wishes — to alter it. Until then, it is entirely up to us to effectuate our survival in humane ways. We have to find a way to articulate the carrying capacity of our home. We don’t have a clue as to how many of us can be accommodated on this piece of earth. We really don’t. There aren’t but so much resources to sustain us if we are 6,500,000,000 now. Before you know it, we’re going to be 13 billion. What we need is men and women who can think on our behalf in the period of their existence.

He is an example. He has tried to surround himself with people who are like-minded and who will tend to and nurture the place we call home, who will attend to and nurture different cultures. We will protect different faiths, provided of course, there is a mutual understanding that the principle is always going to be us as a family.

He’s also a student of Lincoln. And Lincoln is important to you, too.

Sidney Poitier: Lincoln is important to me. Let me just say this about Lincoln. It is not very good that we have really not made a stronger, sustained effort to speak to our children — the black ones, the white ones, the brown ones — about this man. This man. It is because of this man, Lincoln, that we have a President Obama. Because the values of Abraham Lincoln were ignited in President Obama. And President Obama ignited some of Lincoln’s values in his fellow Americans. And if you were to take a listing of the American population two years, four years, five years ago, the possibility of him being what he is today wouldn’t have crossed very many minds. Would not. As a result, here is a guy who says, “I am this…” and “I am imperfect, but yes — and I screwed up here and I did this there, and I’ll tell you about it. And if you can tell me where I can improve, I will listen to you. My responsibility is to represent you.” Well, I find him absolutely glorious, this guy.

It sounds like you see tremendous integrity in him.

Sidney Poitier: Tremendous. Tremendous integrity. Great, great humanity. I wish him well. I don’t know the extent to which it will happen, but I think the world will be the better for him having come this way.

We can say the same of you. Thank you for talking with us today.