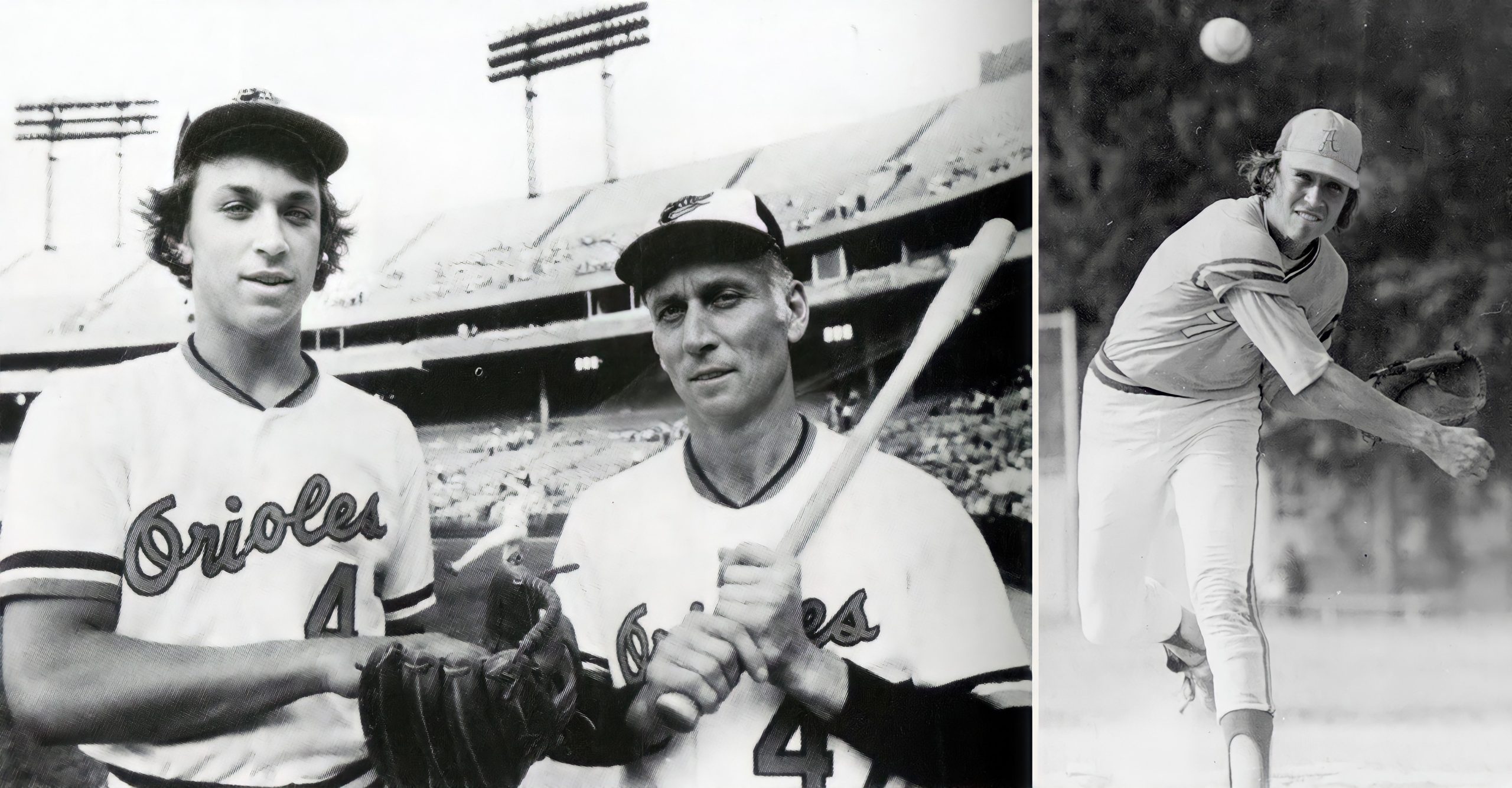

Could you tell us about your first day in the majors?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I made my first trip onto the field, and it’s really weird when you look at my career, you would have never guessed this, my major league debut was as a pinch runner for Ken Singleton at second base, like, in the twelfth inning of a game. So Earl Weaver sent me out of the dugout and said, “Go run for Singleton.” So I went out…

I was 20 years old, turning 21 later that month, but that was before my 21st birthday, and when you ran out on the field for the first time in a real game, like I had taken batting practice, and tried get used to the stadium, now all of sudden people are in the stands, it’s a real game, and the lights are on you. I went out, looking around, and I was in awe, I mean, I was thinking, “Gah!” And then I was so nervous, ‘Don’t mess up, don’t mess up.”

And that was in Baltimore. And Frank White, the second baseman for the Kansas City Royals, he put a pickoff play on the very first play that I was on second base, and I got back safely, and he tagged me, and he laughed, and he laughed, he goes, “Just checking, kid.” You know, he was gauging whether I was too scared to do the right thing. So there was a base hit down the right-field line, and I scored the winning run in that game.

So that was your first Major League game?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Yeah, that was my debut, as a pinch runner, and I would guess that’s the only time that I ever went into the game as a pinch runner.

When that game ended, was your heart pounding? Were people saying you had a lot to live up to?

Cal Ripken Jr.: No, no. The expectations and the pressures hadn’t happened at that point, it was almost like you got your feet wet. I felt like I didn’t really get to play, I got to pinch run, and then I just ran around third, and touched home plate, and we won the game, so that was all cool. We were in a celebratory sense, but I wanted to contribute. I wanted to be in the game, I wanted to play.

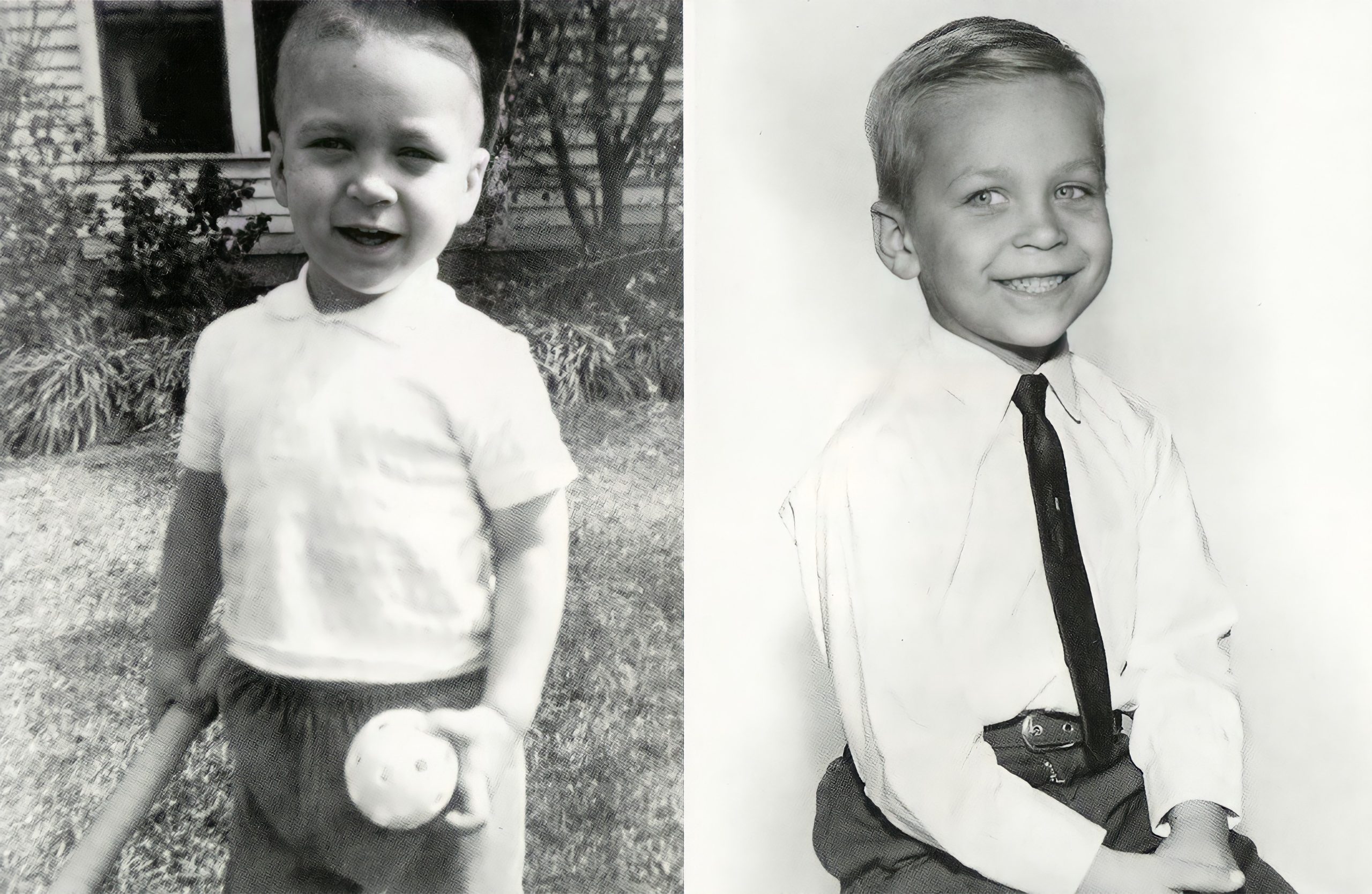

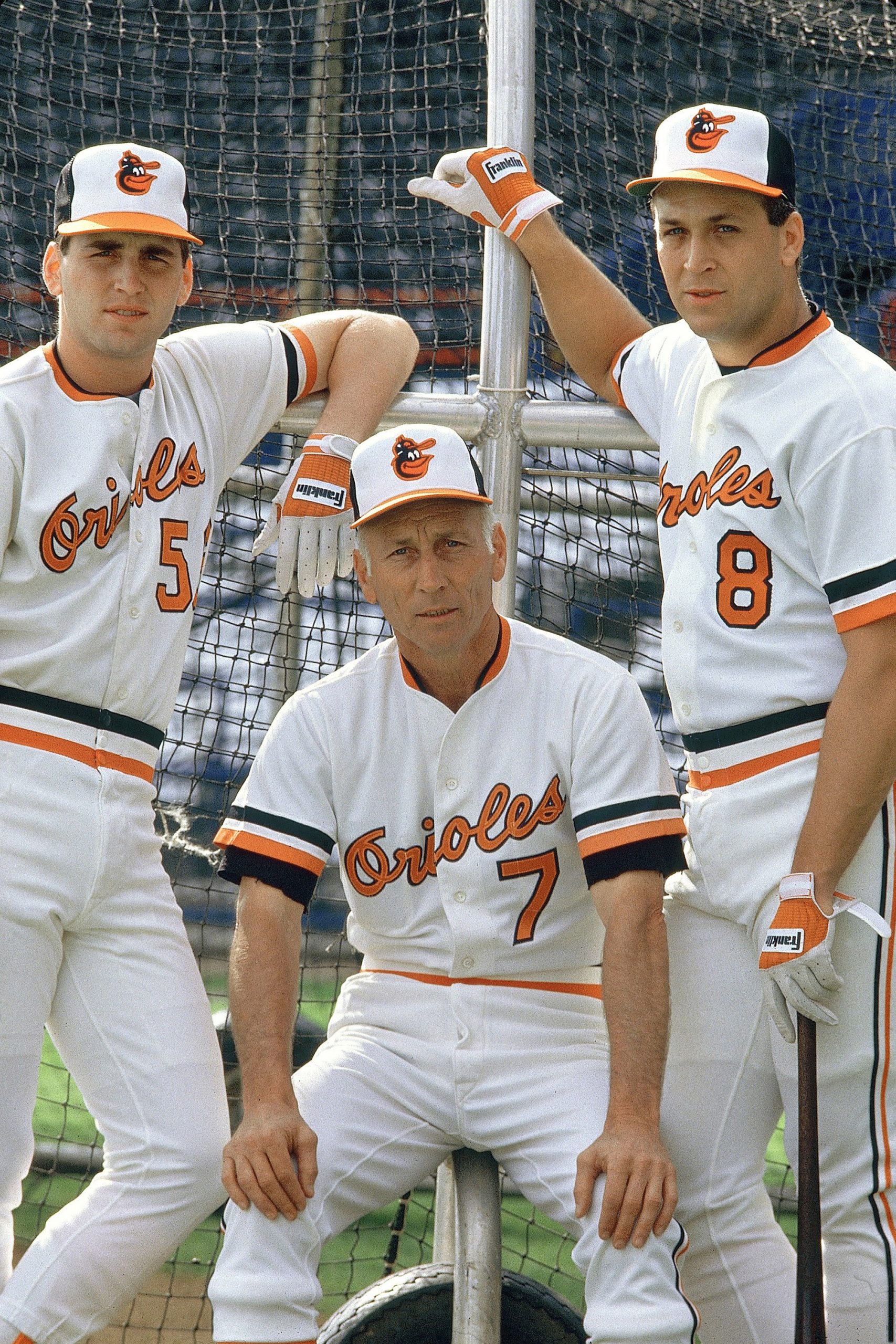

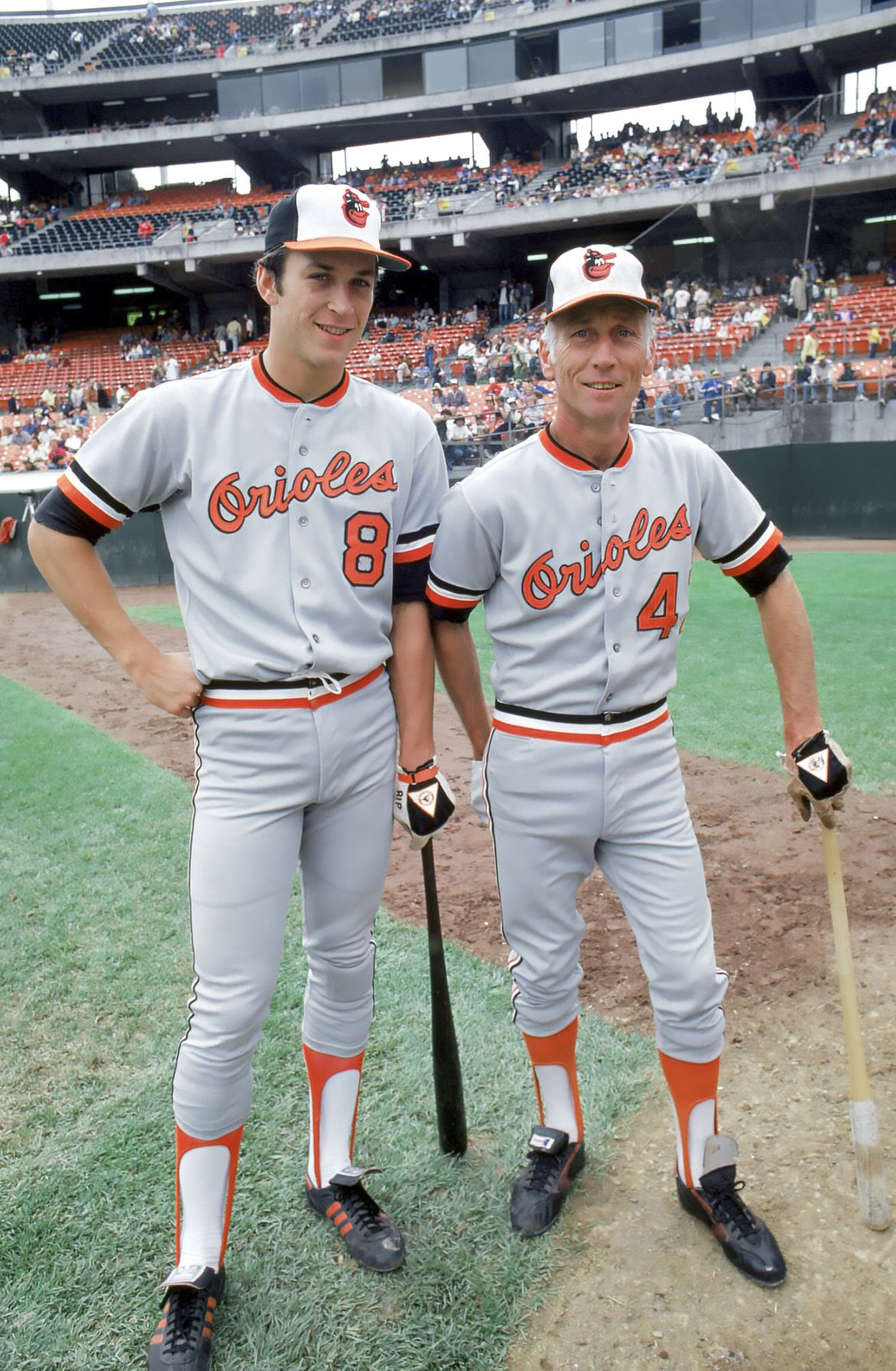

Your father never played in the majors, did he?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Yeah, he got hurt in the minor leagues as a catcher, couldn’t throw for four or five years, at a point when he was 24, 25. They offered him a coaching position, a managing position in the minor leagues. He took it. So his dream was cut short, but he helped fulfill other people’s dreams getting them to the big leagues. Many times being a dad, many times being an instructor, many different things that would help a young man get to the big leagues. That was his role for the first 14 years of my life.

Was he the biggest influence on you?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Oh yeah, I think so.

Was it hard to work for your father?

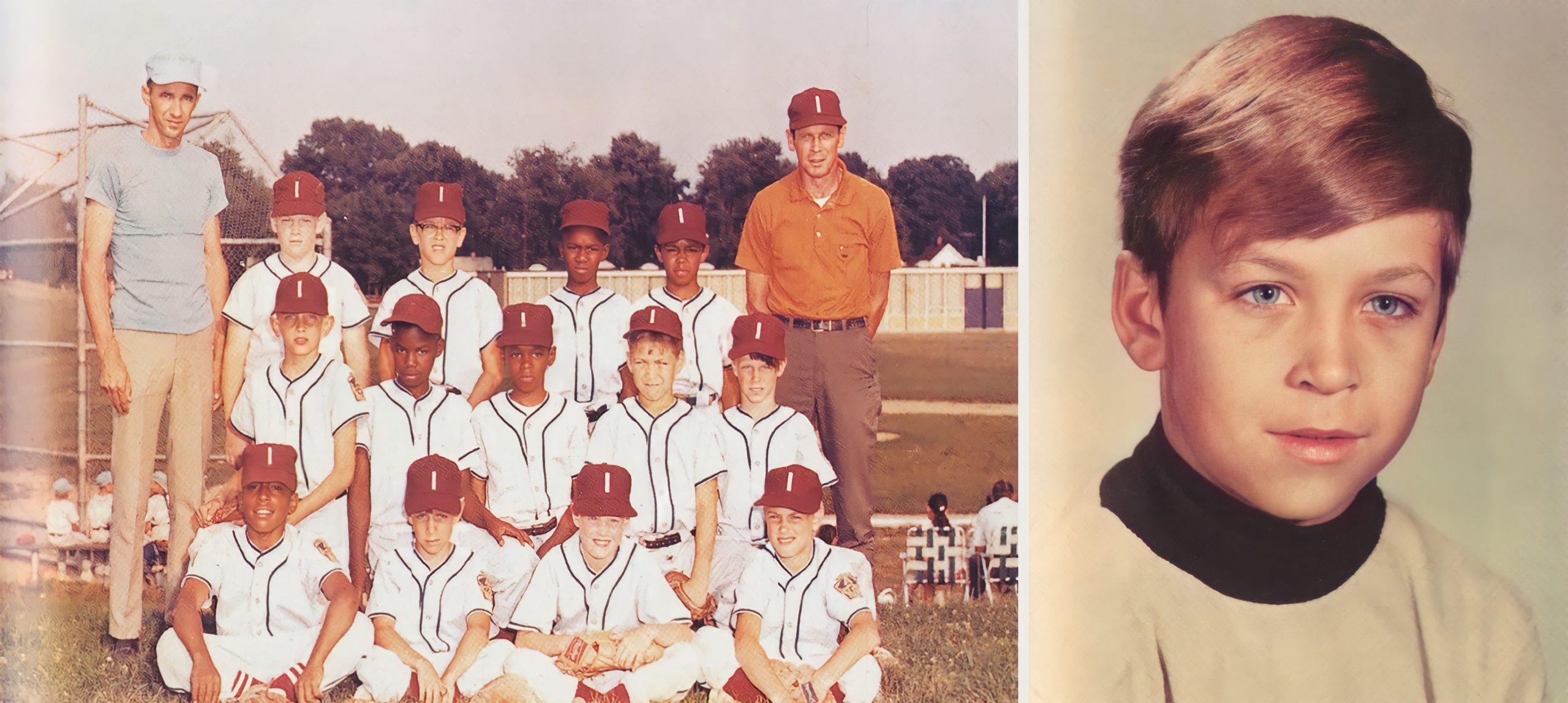

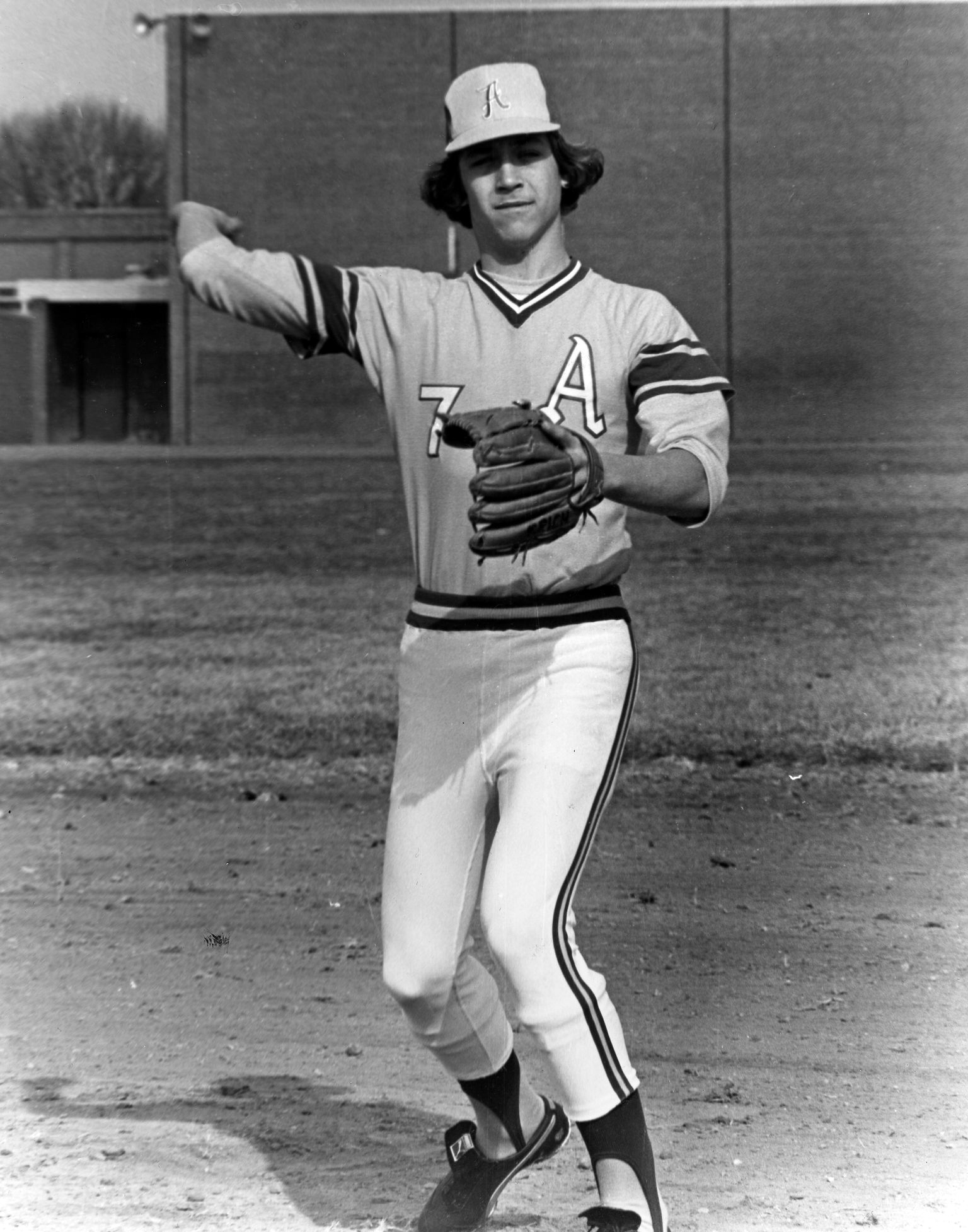

Cal Ripken Jr.: I didn’t think so. I mean, most people think of our situation, my dad was in professional baseball, but he was in the minor leagues. So he didn’t have this big reputation of being a star player, but we were looked at a little bit, um, my brother Billy and I, because we got to the big leagues, I think when you have an experience in Little League, and the coach of a Little League team shows favoritism for his son, who might not deserve to play, there’s this sort of feeling that comes over them, and they associate that.

So, in a professional sense, there was a little bit of that, it was that my dad must have pulled some strings to get you into professional ball, even in the minor leagues when I was leading the team in most offensive categories, and I was considered a prospect, they were – some players who were married, some of their wives said, “Well, he’s only here because his dad got him here.”

How do you deal with that?

Cal Ripken Jr.: It was an added incentive to prove them wrong, in many ways. We all get motivated from different times, but my motivation was to prove those people wrong, and that wasn’t my first priority. My first priority was to make my dad proud of me, and I think most sons want to make their dads proud of them, and in that sport I had an opportunity, and I did.

What kind of influence did your father have on you?

Cal Ripken Jr.: You know, I’m very analytical, and I know my dad is very analytical, tries to figure out things, and tries to understand many different things, and I think he helped me in examining different things in life by pointing them out. There’s a lot of people that can’t take all that in at that same time. So I kept thinking, how do you teach awareness? And I think it’s such a good thing to be aware in this space.

Can you give us an example?

So I remember being in the car with my dad a number of times, and a piece of lumber would be hanging out someone’s trunk, and they’d have a red flag on it, and he’d say, “Why do you think that red flag is on that the back of that lumber?”

And I’d look at it for a minute, I wouldn’t know, and I’d give them a couple of possibilities, and he said, “No, because it sticks out and you want to give attention that it’s sticking out of the back of your car, so, it’s a safety thing.” And one time, the one that blew me away, and I think I wrote about it in my book, is we were in a parking lot and he looks over and sees two of the light standards are bent and the other ones around are not bent.

Like a street light?

Cal Ripken Jr.: A street light, it’s in the middle of a parking lot, and he looks at it for a minute, and he goes, “Why do you think those two lights are bent?” And I go, “I don’t know. Somebody backed into them or something like that.” He goes, he goes, “No.” And he couldn’t figure it out at first, but he sees someone that’s painting the curb that maintains the parking lot and all that kind of stuff, so he walks over to him, and he says, says, “Those lights are bent.” Or something like that. And he saw the snow plow over there — it was in the winter time — and he goes, “Where do you push your snow?” And the guy said, “I push the snow to the middle. We try to keep it to the outside and we push them against those lights.” And so then his answer came to him pretty quickly is, “The snow plow pushes the things up and it bent. The force of the snow plow bent the lights.” And so he came back and he told me.

And you were a kid.

Cal Ripken Jr.: But I was a kid. So by making his curiosity, his intellectual curiosity about how things work, why things were the same way — it was sort of a constant conversation.

When you first got the call, when you were called up to the Majors, can you remember that day?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Yeah, yeah. There are many great stories and I wish I had one that — they deceive you a little bit, and you kind of think that you might be getting released — but then you’re going to the big leagues. There’re all kinds of games that a minor league manager sometimes plays in giving you the news. But in my particular case, the strike in 1981 had baseball stopped, and we were playing in the minor leagues then. They agreed to terms and they came back. So now that baseball was going to happen again, and, I played a game in Syracuse – Syracuse, New York, I played for the Rochester Red Wings. We were on a road trip, but we drove back to Rochester that night. And I remember it was really late at night, 2:30, something like that in the morning. You’re getting ready to go home from the ball park, where the bus came back, and the manager calls me into the office, and says, “Congratulations, you’re going to Baltimore tomorrow.”

In the middle of the night?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Two-thirty in the morning, yeah.

Playing minor league games, did you routinely stay up till 2:30 in the morning?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Well, you work at night. So you play a game at 7:00. Sometimes the game goes past 10:00 or 10:30. Sometimes you work out, your adrenaline is going, you eat afterwards, and then by the time you go to bed it’s 2:30, 2 o’clock in the morning. This particular time, we commuted to Syracuse, which then you add a bus trip in after the game, to come back to your home ballpark, and then you get in your car and drive home. You’ve already eaten at a fast food place on the way back, but yeah, it was — 2:30 in the morning didn’t seem weird to me because that’s part of your schedule.

And what time did you get up?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I don’t think I slept much – 6:30 or 7:00, and I was in the car driving down to Baltimore from Rochester, about a six-hour drive.

Did you drive yourself?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I drove myself, yeah. So you had all these thoughts of excitement. What’s it going to be like? What’s my opportunity?

Did you call your father?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Yeah, I called. I think I woke them up. I think my dad might have already known, because he was on the big league team and they probably had a discussion on who they were going to call up. So he probably knew. I’m pretty certain he knew before.

Do you remember what he or your mom said to you?

Cal Ripken Jr.: No, my dad was very professional, “Congratulations, well-deserved.” You know, “Now it starts,” something like that. So it was almost like I wanted my dad to jump up and down, but my dad was very professional. No favoritism whatsoever. “You earn your way, very honorable…” and he didn’t show that sort of fatherly emotion on the field. But I will tell you, when I hit my first home run, and I’m running around the bases, and he’s the third base coach, and I get to shake hands, I could tell he was my dad.

Was it your dad who told you the story about Wally Pipp?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Wally Pipp! Talk about using it to make a point for someone else, and the commitment to what they do, no matter what they do. It doesn’t have to be in sport. My dad told me that story a long time ago, and there is some truth to that that. “If you don’t play in a game…” I think probably the first time my dad told me this, I was in the minor leagues.

Wally Pipp was a power hitting first baseman that supposedly took a day off — he had a headache or something and took a day off, and then gave an opportunity to a guy named Lou Gehrig, and Lou Gehrig came in and never came out. So essentially Wally Pipp lost his job because he took a day off. And my dad, through the minor leagues, would say, “Okay look, if you want to take a day off and you think you’re tired, and you sit down, and the guy that replaces you gets three hits in a game that night, what do you think the manager is going to do tomorrow? He’s going to want to play the guy that got three hits. Don’t let that guy get three hits.” You know, it’s almost a territorial view of your spot. You’ve earned your spot, you got in there, don’t let anybody else take that away from you. So there is internal competition that exists, not just playing against the other team, but the competitions of your own. There’s people that want to take your job all the time.

Did you really think of that when you were playing all those games?

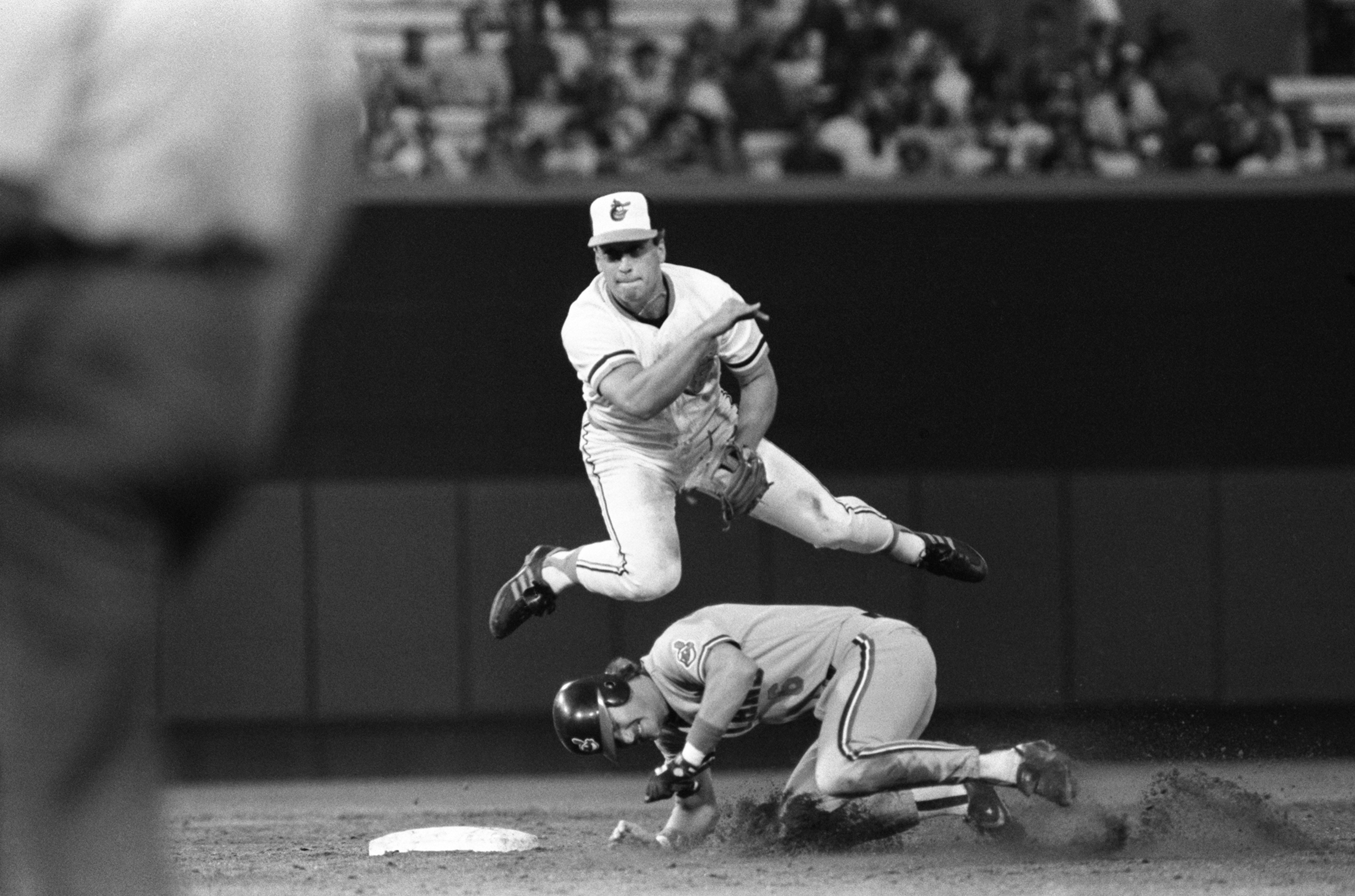

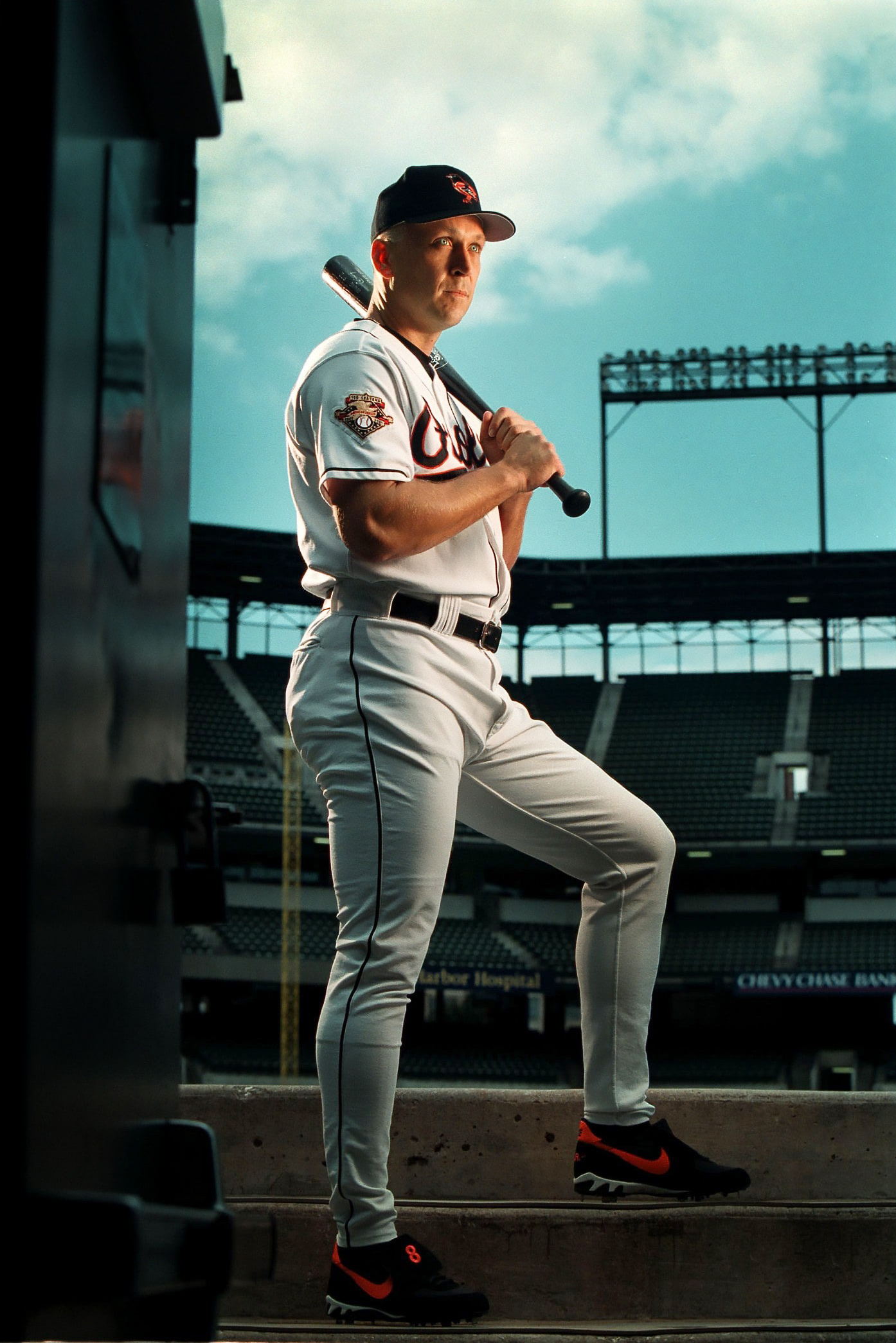

Cal Ripken Jr.: In the early days I did, yes. And I will give you another example. I played shortstop and — Earl Weaver moved me to shortstop — I think it was presented as a temporary move. I played shortstop at almost 6’5, 225 pounds, which no other person at that time, at that size, had success playing the position.

They were mostly shorter guys. You had to be quick.

Cal Ripken Jr.: They had nicknames: Peewee, Scooter, you know? All those guys. Or “the Wizard” — Ozzie Smith — is probably the best that could play that position. Acrobatic, small, could move really well. All of a sudden, when I played that position, it was thought of that I was going to bolster the offense. I was an offensive player. I took great pride in my defense and I did really, really well at defense, and my success at the position might have changed the mindset a little bit for other bigger guys to be considered at that position, but I will tell you every year I went to spring training, there was always some whippersnapper shortstop that was coming in from a trade or coming in through the minor leagues that was going to take my job and move me back to third.

So it was almost like you had to ward that off. You had to say, “Oh, I’m competing to stay at shortstop.” And there were many, many different times where different managers came in, different people, and they had a different opinion whether I could play shortstop. Now I played shortstop for 15 straight years, so that temporary move lasted quite a bit, but it wasn’t without some sort of pushing off the competition to maintain that position.

When you have a clutch play that you blew or you have a particularly bad night…

Cal Ripken Jr.: Never happened. Never happened to me.

How do you get over it? Do you stay up at night and kick yourself?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Well, that’s a process you learn as well. When you play every single day, you can prolong a slump by hanging your head and moping around, you know, after having had a bad night, you struck out so much. My dad used to always say, “Tomorrow is a new day.” And it’s easier said than done, but you have to be able to clean the slate from the game before, and then almost start anew, have a new point. It’s valuable to learn from what happened, from your mistakes, so you don’t make those kinds of mistakes again, you can apply some of that learning. But once you start a new game, you can’t carry that bad feeling from the game to the next game.

Do you have any other tricks or tips to pass on?

Cal Ripken Jr.: No, just the Oriole Way, and probably translated into the Ripken Way, in some ways, through my dad because my dad was part of the Oriole Way. You never get too happy when you’re going well, you never get too low when you’re not. You try to keep an even keel. You look at each and every day as a new opportunity.

But how do you do that? It’s so hard.

Cal Ripken Jr.: It is not easy. It’s easier said. But you have to clean the slate sometimes. Many times if I was troubled, I’d be in the clubhouse a long time. You know, I need to leave it at work, and if I’m troubled, I talk it out, I think about it, I go over all the different things. And sometimes I wouldn’t come home, wouldn’t leave the clubhouse. I didn’t want to go home with that baggage. So I had to, I had to deal with it, however it made me feel.

There were times, I will give you one story which I was – and sometimes you work at it extra hard. You would not punish yourself for something in the weight room for having not done something on the field. One such day I was struggling so bad, I had the game-winning opportunity to drive somebody in, struck out in a key situation in the game, felt like the whole outcome of the game was on my shoulders.

So I was so frustrated, I had my baseball uniform on, I went in, and I ran on the treadmill for like an hour and a half in my uniform, and it was almost like I wanted to — I had the physical need to get this out, and I was like I was punishing myself for not coming through in the clutch. And people kept coming in and out and looking at me. I don’t know what they were thinking about me doing that, but that was my way of physically dealing with that.

And it worked?

Cal Ripken Jr.: It worked.

Is the idea that you don’t want to get too high because you know you’re not going to stay there?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Yeah. If you start bragging, or singing your own praises, or walking around like you’re on top of the world, I always felt that you’re going to be humbled just as quickly. So you’ve got to handle the feeling of superiority sometimes with the same feeling. Like, if you’re hitting really well, you can face the best pitchers in the league, and you feel pretty good. You feel you got a chance. If you’re not hitting really well, other pitchers that you normally hit, you can’t hit either. You can’t hit anybody. So it really starts from within yourself.

In baseball you don’t hit more than you hit, right?

Cal Ripken Jr.: No. I mean if you fail 70 percent of the time, you had a great year. You’re dealing with failure seven out of ten times as a hitter.

During your slump there were news reports or headlines, “Ripken, maybe he should get off the field. Maybe he’s doing this for him and not the team.” Were you ever worried that, yes, I’m playing through the pain, but maybe it’s not the best thing for the team?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Well, I told you I was very analytical, so I would consider all things, and analyze things, but I kept coming back to the same approach, which is that I think that everybody should come to the ballpark. I didn’t make the lineup out. I didn’t. It’s the manager’s job, and “the Streak” wasn’t created by me saying, “You, manager! You, Earl Weaver! You put me in the lineup every day!” The job of a player, in my opinion, is to come to the ballpark, because you’re part of a team, and then the manager chooses who you play. So by the manager’s choices — and there were several different managers — their choices put me in the lineup and I performed. So then you earn your right, deserve your chance, and then there’s a reason why the manager’s writing you into the lineup.

Did Frank Robinson ever speak to you about it?

So “the Streak” was created by these decisions, daily decisions by managers. Now, at some point some managers say, “Well, the Streak is too big and I just had to keep writing his name into the lineup.” I would think that that is sort of shirking your responsibility as a manager. You have a job to do, I have a job to do. All I did was come to the ballpark all the time, but in moments of slump — and the game is a series of slumps. I had plenty of slumps. You have to – Do you believe that you can find the answers by sitting on the bench and then maybe practicing, or you need a mental break and all that? There are all kinds of players. I never thought the answers were in the batting cage or on the bench watching somebody else play.

And the manager would put me in the lineup for a lot of reasons. So, you mentioned Frank Robinson a minute ago. Frank Robinson probably paid me the biggest compliment, and I didn’t know this until after the fact. He said “There were plenty of times when I was a manager where I thought I needed to give you a day off, and I needed to take you out of the lineup. You were struggling as a hitter, you were agonizing over that, and I thought it would be good for you individually if I took you out, and then let you regroup and maybe you’ll come back and hit better.” But he said, “But selfishly, I sat down and I thought about all the other things you did in the course of a game, all the other values that you bring to the table each and every day, is that I didn’t want to take you out. One of the easiest of my jobs as a manager was, I had to wait for someone to come to the ballpark to see if they could play. I had to check with them to see if they could play.” He said, “With you, I knew you could play and I just put you in the lineup.”

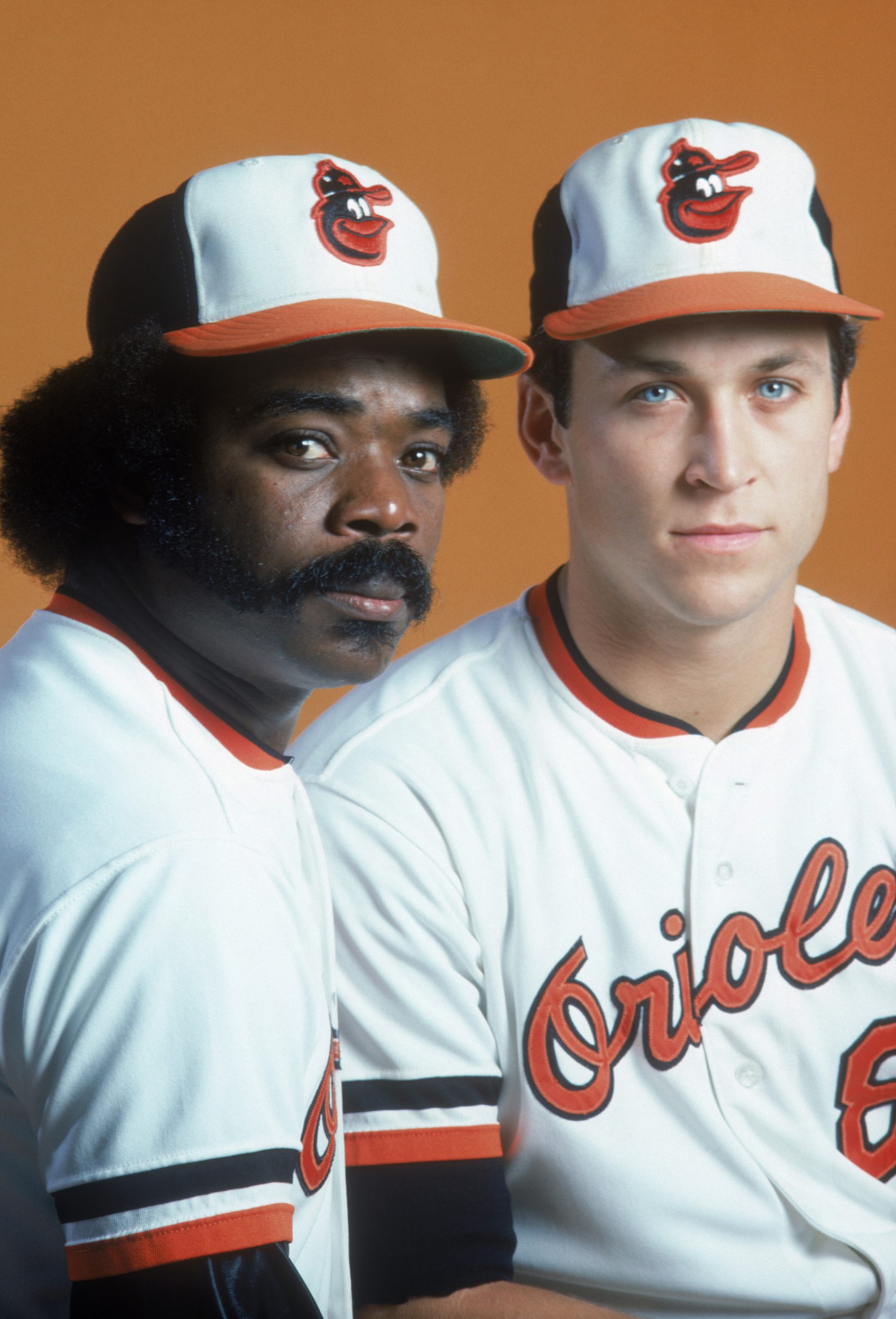

So I think there were these intangible values that — nowadays you’re analyzing everything, so statistically oriented, — and I’m a stat guy. I’m a data guy. I love that, and I love using that to your advantage, but there are intangible values. I mentioned earlier, Eddie Murray’s presence, hitting number four in the lineup, he could be 0 for 75 — which I don’t think he ever was — but even if he was 0 for 75, he allowed me to stay in my slot, he allowed everybody else to stay in their slot. And I tell you what, when the manager looked at the sixth inning of the ballgame and he looked at, do I change my pitcher or not? And we got Eddie Murray coming up, he affected the manager’s decision just by his presence.

Do you think in the days of Moneyball and everybody talking about stats to the tenth power in baseball, that there is too much emphasis on just the math?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Yeah. I think things shift and evolve, and sometimes the balance of things gets out of whack. There’s good baseball understanding. The thing about all the numbers and the stats and all that kind of stuff, is you got to figure out how do they help me be a better baseball player? What do I apply? How do we become a better team? And sometimes there might be too much emphasis on the stats, and the baseball stats and maybe some of the analysis is not really good. But then it’s also — sometimes you rely too much on the subjective, and your feeling on what happens, whether I should pinch hit this guy or not, and you might go the other way. So, my dad used to say, “In baseball, every ten years or so there’s sort of a cycle, that somebody will think that this hasn’t been tried before, and they try something in the game only to find out that the game has been going on a long time and this has been tried.” So I don’t look at it as all or nothing. There is sort of a change right now where the numbers guys are looking at how to teach to the numbers and how to do all that kind of stuff, and the baseball piece will start to come back and it’ll all merge in a way that everybody is happy with.

Is that why there is so much baseball trivia?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I think the beauty of being able to compare statistics over time, baseball has been ahead of other sports, like the home run records and stuff like that. Now steroids have probably changed people’s view of some of these records. It used to be 30 home runs was a big home run year, and then all of a sudden, the number went up — 500 home runs was almost — there were only a few people in the history of baseball that did that. Now steroids have changed some of the inflation of some of those numbers.

How damaging was that scandal, when people found out that their heroes had been taking steroids?

Cal Ripken Jr.: How damaging to baseball? I think for those that really looked at comparing great players from one era to other eras, I think it took the air out of them. In a lot of ways, and in some ways the athlete is bigger, stronger, faster anyway, and the game evolves, and I’m probably most proud of that I was able to put a little bit of mark on the game and hopefully make the game better for the next people that play the game.

What mark do you think you made on the game?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Whether it’s “the Streak,” or whether it’s my success as a shortstop, whether it’s — I got 3,000 hits — whatever I was able to do that might better the game or leave a positive mark on it, I personally think the game should get better and better over time, as the athletes understand the game. Conditioning is better. Steroids kind of put a blurp in there. I don’t know to what extent it still is in the game or not.

How many balls have you been hit by?

Cal Ripken Jr.: That’s kind of a funny story. Some people just stand there and get hit. Some people think it’s a manly sort of thing, saying, “Okay, it’s not going to hurt me. I’ll take the ‘hit by pitch’ and go to first base.” I was never of that opinion. I would rather get out of the way of the ball, and I was pretty good at getting out of the way. I stood off the plate a little bit.

It’s kind of funny, my son when he first started playing baseball as a — I don’t know — eight-year-old, there was a period he got hit and he was kind of scared of the ball. And I was trying to say, “It’s part of the game. You can’t hit by being scared or thinking you’re going to get hit. You have to have the confidence that you can get out of the way.” So I took a tennis ball or a squishy ball in there, and I gave him some techniques, and I started to throw the ball inside, and then I said, “Look, I’m going to try to hit you with this soft ball now. See if I can.” So we invented a game called — sort of dodge ball, a little bit — and he became pretty good at getting out of the way.

And I said, “Is there anybody on your team that gets hit all the time?” And I said, “Yeah, this catcher gets hit all the time.” And I go, “Why do you think it is?” And he says, “Because he just stands, he doesn’t get out of the way.” I said, “Right. You don’t have to worry about it because you can get out of the way of the ball.” So that’s how I thought. I got hit enough times. I got hit in the head, I think, seven times. I counted it up one time, and every single time I got hit in the head I was looking for a breaking ball, which you have to wait, and convince yourself that it’s going to break.

What does it feel like when it’s coming at you, going 90 miles an hour more?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Sometimes it starts right here, and if you’re waiting longer to make sure it breaks, and all of a sudden, it’s not the pitch you’re looking for, then it’s a fastball, and you put yourself in danger. So each time that happened it doesn’t feel good. When it hits you in the helmet, you’re thankful that you have a helmet on, number one.

You talk about looking at the ball as it comes at you. Let’s talk about your eyesight.

Cal Ripken Jr.: My eyesight? I always prided myself on it. I could see really well, and I could pick up spin really well.

Is it better than normal eyesight?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Yeah, it’s like 20-10, I think.

How has that helped you?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Well it has to be able to help you, because you have to identify the ball and sometimes the spin of the ball. You have to see it. I will tell you, I was happiest when we went into spring training. Sometimes you get poked and prodded from the medical staff and all that kind of stuff as part of your spring training. They’re doing all kinds of tests on you and all that kind of stuff, which is good, and one of the tests is your eye test. I remember, after you get your eye tested for the first couple of times and the same people do the eye test, they start bragging on you that you can see this line or your eyes are really that good, and it always made me feel good. They always built me up so when I took the eye test and performed really well and read the bottom line or something on it, they would stick their chest out and be proud of me.

You have very light-colored eyes. Was that ever an issue?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I always thought that day games were difficult for me, because the glare, whether it’s bouncing off your cheeks, I always felt like I had to squint. So I always try to put eye black under my eyes, and I even tried to wear some glasses, but it was difficult to play in the daytime sometimes for me, because it felt like you would wear your eyes out by squinting. You would wear the muscles out.

Hank Aaron said he would rest in a dark room before a game to save his eyes.

Sometimes, early on in my baseball career, since there’s a lot of downtime in traveling, and you’re on the road, and you’re on a plane, and all that kind of stuff… I got drafted straight out of high school. I was a good student in high school, but I didn’t get a chance to go to college. So I thought that I would use my opportunity with some downtime to educate myself, to read on subjects about history or things that you wanted to read about. I found myself reading a lot, and feeling good that I was educating myself, but I was wearing my eyes out.

So you get to home plate, at 7 o’clock at night, after you’ve read in your hotel room, and all of a sudden, you’re not as alert, and you’re not crisp, it’s not clear. It feels like things are blurry. And I kept thinking, “Okay, I got to stop this reading.” And then when I stopped doing that, and then you would stay in a dark room, similar to Hank (Aaron). You had to understand, and this is part about learning about yourself, is you have to understand the most important time for my eyes to be really alive is when I’m at home plate. So you geared your behaviors during the course of the day so that you can have the best chance to see.

So would you stay a dark room before a game?

Cal Ripken Jr.: No, I didn’t take the analysis to that deep of a level. I just tried not to do things that would tire your eyeballs out.

What would do that, besides reading?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Reading a computer. I bought a laptop computer and I was learning about databases and word processing, and I was educating myself with this laptop.

Do you listen to a lot of audio books now?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I do. I found out that a quiet room, dark shades in a room, and even watching a movie didn’t tire my eyes out as nearly as much as doing some of the other stuff that required you to be in front of a computer. But audio books is one of the ways that I did that, and in those days, they were all cassettes, and you have all these different… Nowadays, you can just do it digitally, and it’s a whole lot better. Have someone read to you and just close to your eyes. That was the way that I got around it.

What interested you?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I had a big interest, mostly in non-fiction stuff. I like historical… A book on tape or something, you can go in the car – that’s another thing I did — I put in a book on tape, a self-help book sometimes, or whatever else, and you would listen 30 minutes on the way there, and the way back. So that handled my education without hurting my eyes.

The football field is always exactly the same. The dimensions of the basketball court are always the same, but a quirky thing about baseball is that ballparks can be very different. There are hitters’ parks, there’s one where the infield is shorter, right. You don’t have to hit as far. They’re all different.

Cal Ripken Jr.: The mound is always 60 feet, six inches. It’s supposed to be 12 inches tall, but many stadiums push it up a little higher. It’s interesting. I thought Seattle looked like their mound was like 20 inches tall and you have Randy Johnson standing on top of that, and it seemed like he was throwing at a different angle, but the bases are always the same, and the mound is the same.

So you have those references that you can play. Especially as an infielder that’s important to understand where you play as it relates to those constant references. But the fences were different. Playing in Fenway Park was really cool. It was a museum type experience because the Big Green Monster, it was so close, it changed the way you played a little bit, it changed some of the responsibilities. Like, as a shortstop, a fly ball to left field, and the left fielder goes back against the wall, and it hits off the wall, and he doesn’t quite catch it. The closest person to that ball is me, as a shortstop, and normally in any other ballpark that’s not the case, the centerfielder is coming over, I have a responsibility to be someplace else.

But did you like Fenway?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I loved the understanding that took. That you had to look at the ballpark and you had to change your game a little bit, and some of your responsibilities. We talk about awareness. You had to be aware of these things so you could react to them properly. It used to be you went into Fenway, they hit a ball off the wall it was a double, because our left fielder didn’t know how to play the ball off the wall. If we hit a bullet off the wall, it’s a single. It was a little thing.

You go to the Metro Dome in Minnesota. The ball could be lost in the lights or in the lights in the ceiling, ceiling mostly, because it has a big old ceiling, and the ceiling color is the same as the ball, so if a high fly-ball went up, and you took your eye off it, and tried to pick it back up again, you couldn’t. So, you had to remind yourself of those things. The Minnesota Twins, I’d watch them, and they all would get together in a cluster. Like say the ball was up and it was in the middle of the diamond, you got the first baseman, you got the second baseman, the shortstop kind of converging, and they’re looking, “Do you see it?” “No, I don’t see it. Do you see it?” “Yeah, I see it. Okay, I’ll take it.”

So there was this extra conversation that took place where they grouped it, because they understood what happened, and if the ball hit the turf it bounced really high. If you knew of all those things you could take advantage of those. And Minnesota had a home field advantage. They hit a blooper to right-center field, they weren’t thinking just a single, that the guy was going to come in, they were thinking it was going to hit and hang in the air, and we’ll take that extra base. So I loved figuring out different ballparks and how you can make that ballpark work for your game.

Which ballpark was your least favorite?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I don’t know if I had a least favorite. Fenway was interesting and it was a cool place, but you banged your head on the dugout every inning because it was older and it was built for the player that was smaller at that time. I was six foot four, so I left there with a bunch of bruises on my head. Old Tigers Stadium was similar, you know, the dugouts were small, and it was hard to see the whole game, but it was really a cool space in which to play.

I will tell you, Yankee Stadium you had your ups and downs in, because I had been in that ballpark when we were really good and they were not. So there wasn’t a whole lot of action going on, there wasn’t a whole lot of interest going on, and so it wasn’t that great. I had been in that ballpark when we were really bad and the Yankees were really good, and then they all yell at you, and they beat up on you, and that’s not fun.

But when you’re good and they’re good, the same year, same time, and you go into a September series, basically with the American League East title on the line — that happened a few times in my career where this four-game series could change the way that the whole season happens, the fans in New York were so reactive they didn’t need any scoreboard to prompt them to cheer. They knew when a big pitch was happening, and a one-to-one pitch in the first inning, in a key situation and that place would be rocking. So there were times when, in order to play, you have to zone all that out. You’re hitting and you’re fielding, and all that kind of stuff, you can’t be worrying about all that.

There were times in Yankee Stadium when I was walking to the mound, pitcher and coach were coming out to talk to the pitcher for a second, calm him down to buy a little time. We might have a lead in a game by one run, they just have their lead-off hitter on base, and all of a sudden, they can anticipate, Derek Jeter was coming to the plate, or something. They’re anticipating that something good was going to happen and this place is rocking. You could take yourself out of the baseball mode, and it felt like it was the loudest outdoor place, and it felt like the stands were kind of bouncing a little bit, and you would think to yourself, “Man, this is cool!” And then you’d walk back to the position of shortstop and try to zone it all out again.

How do you get down from that excitement level?

Cal Ripken Jr.: You learn how to do that because you learn yourself, but there were moments that you allowed yourself to take in how cool it was, but most of the time you had to keep that game face on.

What was the most emotional moment you’ve ever had on the field?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Hmm, you want an example, don’t you?

Yeah, that would be nice if you could remember a moment.

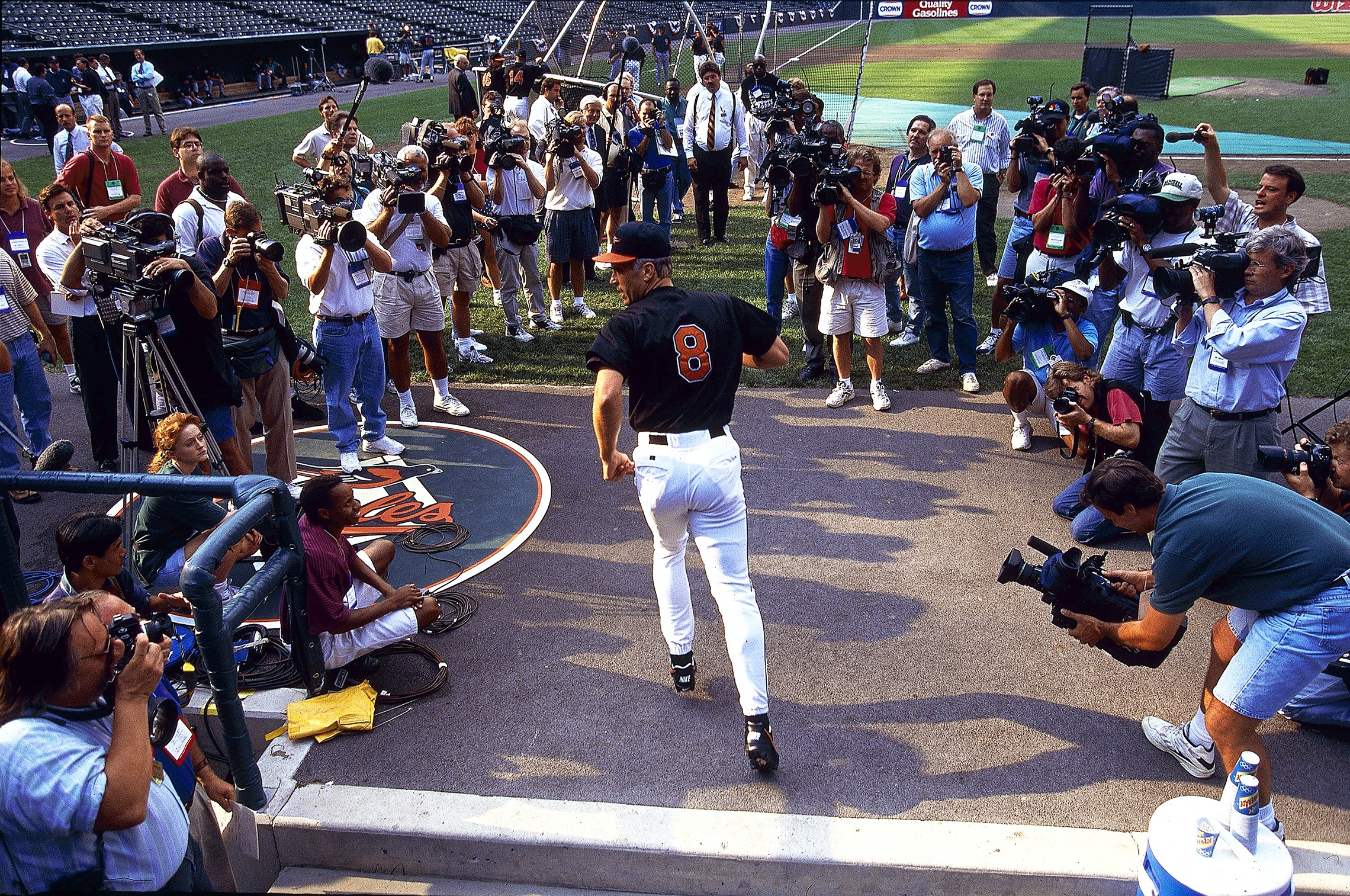

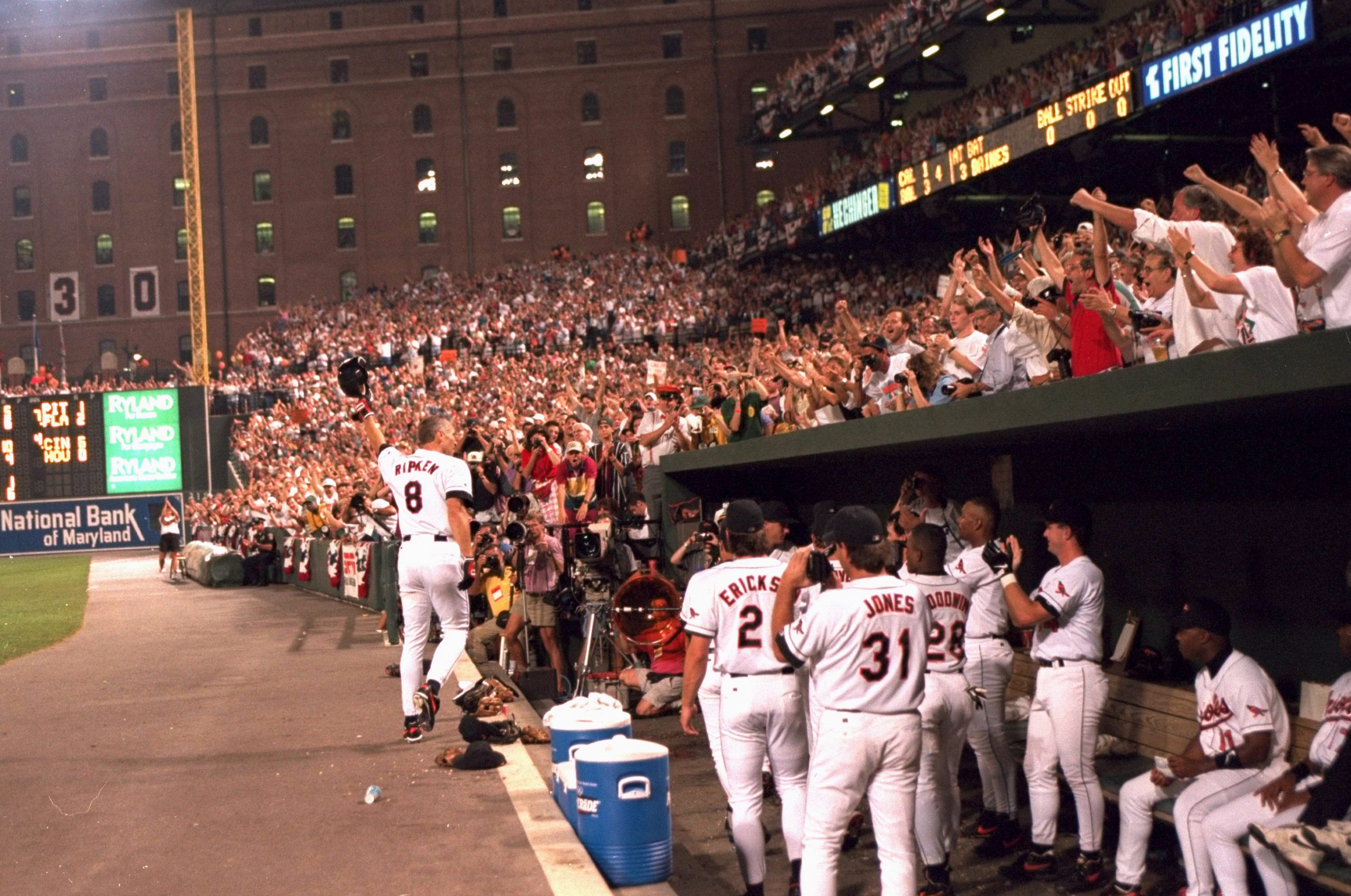

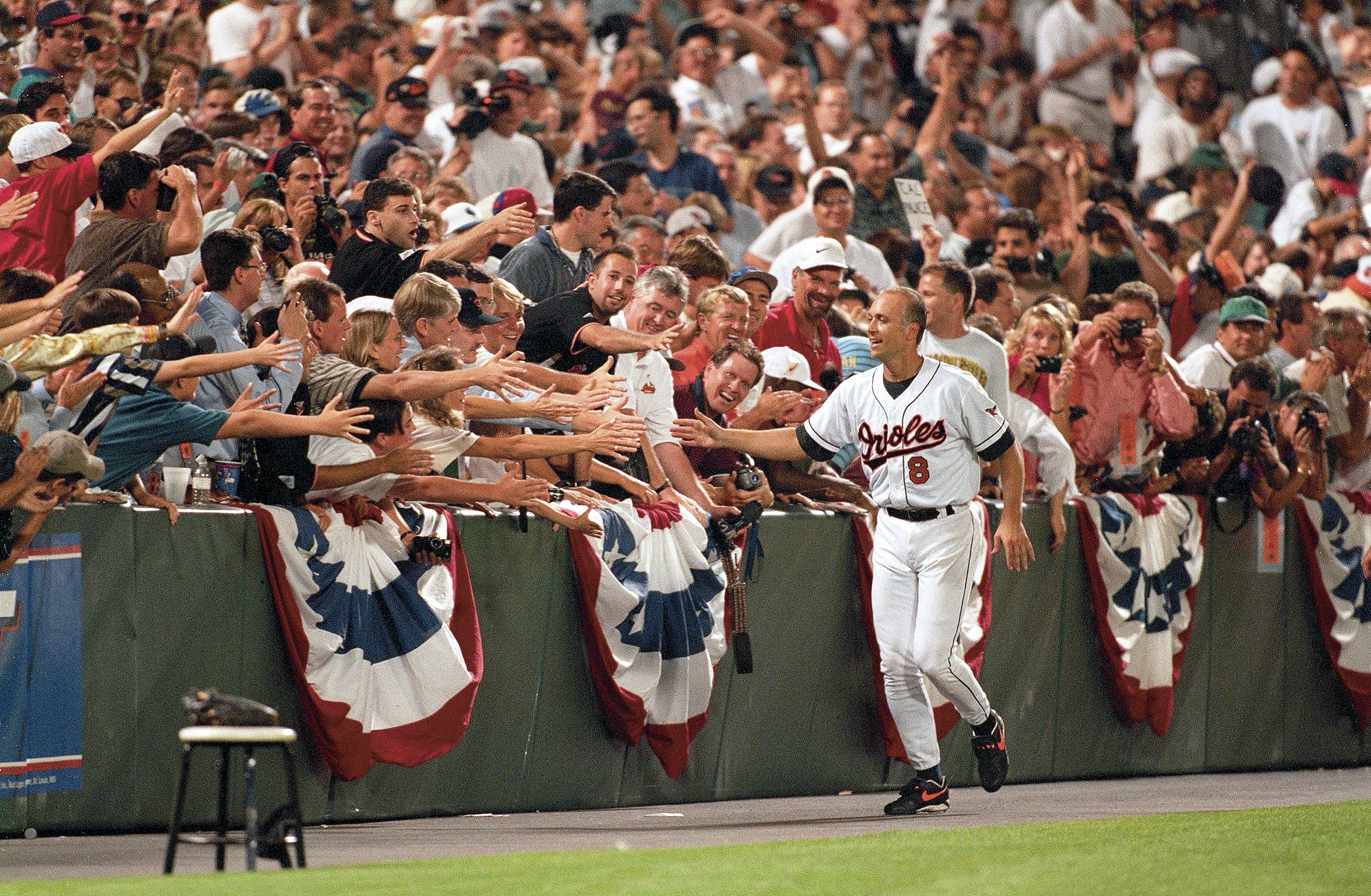

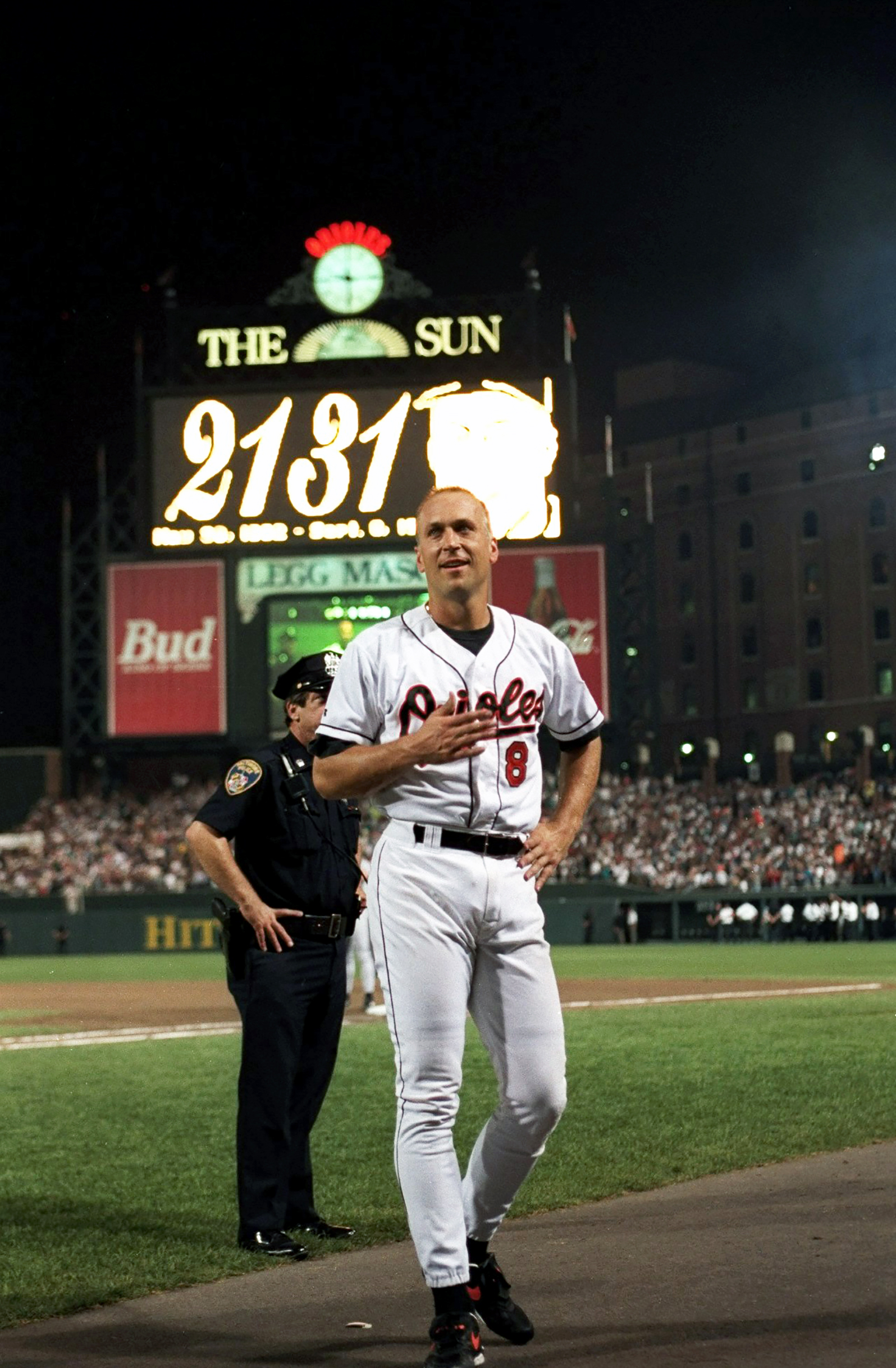

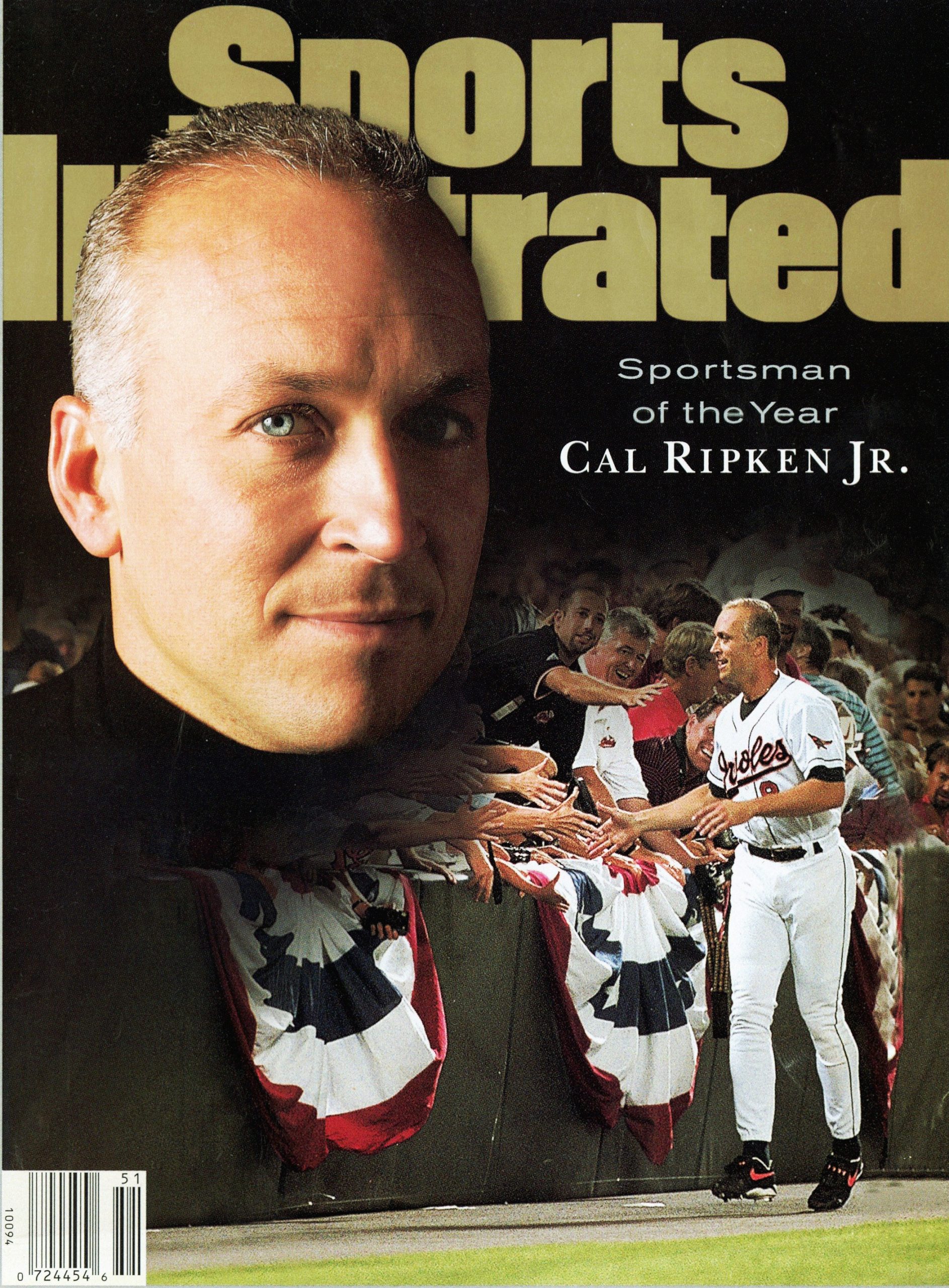

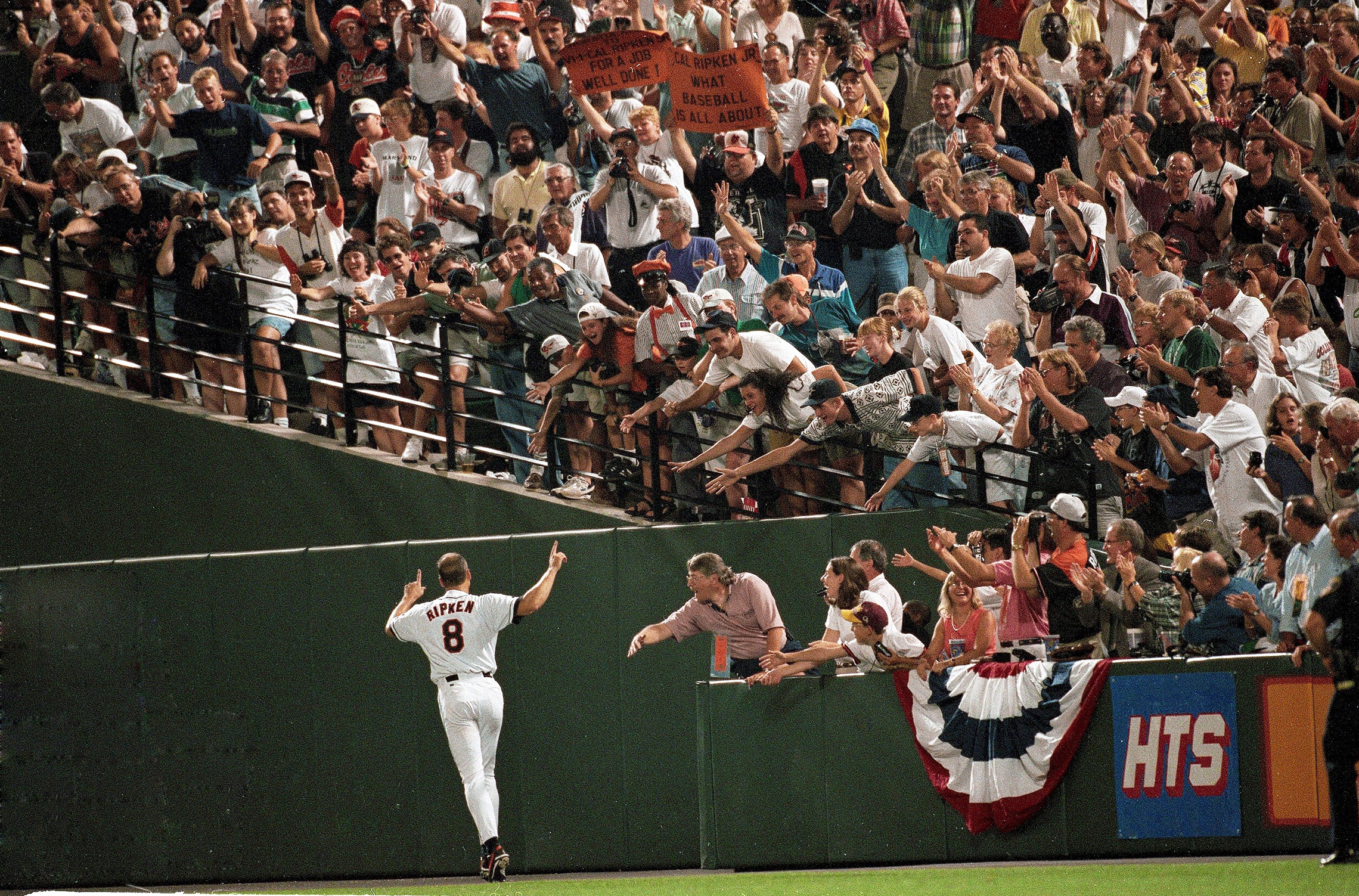

Cal Ripken Jr.: I homered in (games) 2129, 2130 and 2131. So I hit a home run in three straight games, and it was really important to perform, but I mean, my adrenaline was pumping pretty hard, and you had to try to calm that feeling down, that emotional feeling of expectation that was happening.

My last All-Star Game. You would think after all these years, 21 years, I’m in my last All-Star Game in Seattle. I come to the plate and they give me a standing ovation, and then I have to step out of the batter’s box and acknowledge. It’s my last year, I said I was retiring. It was a send-off, and it was part just a great cheer, and I remember stepping back and I got a little emotional, because you’re starting – In your last year, when you announce that you’re retiring, every time you do something, it’s the last time you’re doing it in some ways. It’s the last time I’m going to Chicago, the last time I’m going to Toronto, last time I’m going here, and you’ve had all this time. It’s my last All-Star Game.

So when I was up there, I could feel the emotions filling up inside of me, and then pulling back. It was a cool and special moment, but then you had to hit! So then you had to get back in there and hit. So you have to talk about how quickly you change. You have to take all this great stuff that’s going on, and go boom! And get back in there, and lucky enough on the first pitch I hit a home run, and I run around the bases, and sometimes it’s one of those things. A “How did I do that?” sort of thing.

That ball was going over 90 miles an hour.

Cal Ripken Jr.: Yeah, 95 miles an hour.

How do you see a 90 mile-an-hour ball?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I wish I could tell you exactly how I do it, because I would have done it every pitch, but what I’m saying is when you get comfortable in your environment, and you get comfortable playing, and you can relax to a point where your concentration goes to that level, then you’ve achieved the ultimate. So the idea is: To what degree can I keep myself in that moment? And I found myself, over the years, you say, “How did I hit in pressure?” I don’t think I was much greater than anybody else in pressure.

I mean, I came through with some clutch hits and I rose to the occasion on a number of times, and people thought that was amazing, but I remember getting an opportunity to play in All-Star Games from a very early time. I ended up playing 19 All-Star Games. I was going to say, “Do you know how many I played in?” But in the early days, I was scared to death because you make the All-Star team, there’s one game being played that day, all the other games people are off for the All-Star break, and you have the best of the American League playing the best of the National League in the All-Star Game. And, so all your players are watching, everybody around the world is watching, and I kept thinking, “Don’t embarrass yourself.”

So I was very cautious, you know saying, “Okay, don’t take chances. Don’t embarrass yourself. Don’t be overaggressive at home plate.” But then I found out, by doing that you couldn’t succeed. You have to take some chances, and so I learned how to control some of my emotions, and I learned that if I stayed within myself and I breathed a little bit and say, “Okay, don’t try too hard.” I talk to myself. Sometimes I get out of the box and go, “Okay, calm down.”

What else do you say to yourself?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Sometimes I’d call myself names if I did something wrong.

Any you can repeat here?

Cal Ripken Jr.: No! I was pretty hard on myself, but you would calm yourself down just by having that little conversation, reminding yourself of things. Okay, you’re in the moment. If I put a good swing on the ball, good things happen. You don’t try to hit a home run, just the hit ball hard, and if you reminded yourself then you could control that at-bat.

Who was the hardest pitcher to hit?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Almost all of them. I will say the guys that are in the Hall of Fame now, they end up seeing — every induction year when you go up, they’re generally all the number ones. There is truth. The number one starter on the team — and if you’re lucky you might have two number one starters — the number one starter on your team are at a different level, and then everybody else is… Although they’re good and they have great stuff, they’re not the same challenge. The Randy Johnsons, the Nolan Ryans, the Roger Clemenses, all those guys that were very difficult to hit. The challenge is going to be at the highest level. Pedro Martinez probably had the best year and had the best stuff of anybody I’d ever seen. He had the best fastball that year in the league, he had the best curveball, and he had the best changeup. And even if you guessed right, it was very difficult to square the ball up and have success off him. And he was on such a big roll.

Can you remember anything someone said to distract you when you were trying to bat?

Cal Ripken Jr.: God, that’s such a touchy issue! There should be some honor in the game that when you’re playing, and you’re competing against somebody in the other way, that there’s certain things that you wouldn’t do. But I’m not saying the catcher never tried to get inside your head, or you didn’t try to get inside his head a little bit, but for the most part, there was a respect that they didn’t rag on you when you were trying to hit and all that kind of stuff.

I remember my dad’s story and the times when he played, and he was a catcher, he would do that, or somebody tried to do that to him, he would step out of the batter’s box and said, “Look, if you keep talking I’m going to hit you right in the mask with this bat!” And then it would stop all the chatter and then go back in. But I can tell you, you can use any sort of getting inside your head to your advantage by proving somebody wrong. And many times, because you do it so often, you’re playing the game so often that if you’re struggling, there was an old saying that is you should let them struggle. Don’t wake them up. You can wake somebody else up by doing those things that you’re talking about or provoking them. Or sometimes throwing at you, you might wake the hitter up to a point of concentration, and then you pay for it.

Wake them up by insulting them or trash talking them?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Yeah. Sometimes, however the game, however the competition goes. If someone is going through the motions and trying to figure out how to hit, and they’re not hitting, and they’re in a slump, you want to let a sleeping dog lie.

If they’re on the other team?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Right, and maybe there are sometimes you can motivate. Earl Weaver was very good at motivating his own players, sometimes waking them up. So managers had different techniques, but I never had a problem. I learned myself. I think the most important thing about playing, and playing at a high pressure situation, or playing at the highest level is to understand yourself, and to understand yourself in all situations. Don’t try to be like — for me, to be like Eddie Murray — or someone else. Use some of the advice that they might give you but learn yourself.

Just recently, there’s been a scandal about a team using cameras to steal another team’s signals.

Cal Ripken Jr.: I have a different opinion of that. There is a standard of how you play the game. If you’ve read — I think the name of the chapter in the book, that was “Playing Fair” — is I don’t believe when you’re playing against the pitcher, and I’m the hitter against the pitcher, I don’t believe the challenge is between me, the pitcher, and the guy on second base.

So if the guy on second base has decoded the signals from the catcher, should he be allowed to relay the signs to me and they’ll let me know what’s coming? YI thought that’s not in the spirit of competition. But I could be in the minority, with most baseball players saying, “Well, you earned my right to get to second base, and if you don’t, if you don’t put down a sequence of signs that, that stops them from doing that then it’s your fault.”

But do you think there was something wrong with doing that?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I don’t like the cameras. I mean, if you’re standing on the on-deck circle, and you see the catcher move inside and then you verbally tell the hitter in some code that the catcher is sitting inside, I don’t think it’s in the spirit of the competition. So I never gave a sign from second base and I never received one. If, with your own eyes, if you see things that are going on, say I’m on second base, and I can decode because I’m a middle infielder, and I’ve seen a lot of different situations. The way that they disguise their signals. I’ve seen many different options in the way they disguise their signals.

There could be a first sign indicator, there could be a sign after two, there could be the third sign, it could be the first sign after one. You could change this, usually it’s a fastball, two is a curveball, three is a slider, and wiggle is a changeup. You could change the meaning of those. One could be a curveball.

There could be all kinds of creative ways. I think the hardest one I’ve ever seen, and I’ll share this with you, it was called “Abe” — A-B-E. So what A stands for is “ahead,” B stands for “behind,” and then E stands for “even.” So it was all about the count. So if the count starts 0-0, what’s that tell you? It’s an even count, so it’s the third sign. If the count goes 1-0, then you’re behind in the count, then it’s a head behind, that’s the second sign. If the count goes 0-1. So it’s always about the count.

You always have to be in tune with the count to understand which pitch is going on. Now, that could be confusing because you want to get into a rhythm and the catcher is going, “Okay, what’s the count?” He should know the count and all that, but infielders are trying to figure out, pitchers sometimes are throwing the wrong pitch, and then you get out of your rhythm. So you can be too complicated. You can mess yourself by the complexity of your signals. But if you make them too simple, somebody else on second base can see.

So if I’m a base stealer, which I wasn’t, but I would think it’s okay, if I’m on second base, and I’m on second base for a couple of pitches, and I see the signals going down, I say, “Okay, he’s going to throw a curveball on this pitch,” which is a slower pitch. There’s a chance it’s going to be in the dirt. This might be a good pitch to run on. I would think that it’s totally all right that I’ve used that for my own advantage to play. That’s in the spirit of the competition. But I don’t agree with me figuring out the signs and then transferring them to somebody else, or getting them through a centerfield camera, or getting them through watching a feed and then banging the trashcan in the bottom. I don’t think that’s the right spirit of how you play, so I wouldn’t do that.

What’s the message there?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I think there’s certain rules. I’m generally a rule follower and you don’t stretch the grey rules. You try to take advantage of what the rules are that you can incorporate in the game.

Yet everyone is trying to get that tiniest edge.

Cal Ripken Jr.: I’ll tell you what. In the Electronic Age, I don’t know whether buzzers or anything else are true, but if you have an electronic indicator on you, and then somebody is telling what’s coming by buzzing you or whatever else, that makes hitting way easier, and it’s not right. The challenge is to try to figure out the pitcher. The pitcher is trying to figure out you. It’s a competition. It’s just between you and him.

What if one side is doing it and not the other?

Cal Ripken Jr.: The cheating has been around. For years there was a guy sitting in the scoreboard in Chicago, supposedly, and he was turning a light bulb on and off with binoculars, he could see the catcher’s signs. Those stories have been around for baseball for a long, long time. And there’s some feeling that within the story, that some stealing of signs, — like I gave the example of second base — should be okay. Or if a catcher puts his fingers down too low, in your own first base, and you can see the signals. Or a pitcher tipping his pitches, you know. If a pitcher tips his pitches in a way that gives you an indication. Like, sometimes the pitcher will grip the ball right in front of you. So if he holds to your side and he holds it this way, it’s a fastball, and if he holds this way, it’s a curveball. So that’s, that’s giving you an indication.

If I look at the pitcher, which I’m staring at the pitcher, it’s my competition, and I look down at his hand, and he’s holding the ball this way, and every time he does that he throws a curveball then I’m going, “Okay, I can use that.” It’s not that somebody else is stealing that and telling me. I can use that to my advantage, in the spirit of the competition.

Do you think a 162-game season is too long?

Cal Ripken Jr.: No! My brother Billy and I joke all the time. We try to figure out, when you get to the playoffs, it used to be the 162 challenges you, your whole team, your depth, it challenges every single day of who is the best team in the league that particular year. And it used to be whoever won the American League and 162 on a balanced schedule, it would go right to the World Series, and the National League, whoever won that will go to the World Series. So the two best teams proven by the 162, by the depth of your team, and about getting to the finish line, you’re the best team in the league that year, and one of the two best teams in the league is going to be the world’s champion.

Now, once you expand the playoffs and you have different divisions, it’s who is the hot team that ends up kind of winning. If you’re a wildcard team and you develop some momentum, and you’re almost — you’re one out from going home and you get past that — then all of a sudden it seems like you’re playing with house cards. You relax, things go your way, and any team can beat any other team. But the depth of your team with off days and all that kind of stuff isn’t always challenged. So sometimes you can have one pitcher that pitches game one, four, and seven in a seven-game series and impact that World Series in a bigger way.

So Billy and I kind of joke, and maybe you find this out in a situation like this year. You figure out, it would be cool if you put both teams in the World Series, guys who go on to the World Series in one city and you play seven straight games, and so the depth of your team matters. Your decisions you make in game one, and game two and three, affect you as you go along. And then find out who wins in a seven-game series with no off-days, you play in the same place. Now, there’s a lot of hurdles to get past during that is that the teams that are waiting to get to the World Series, who want to celebrate that World Series in their hometown, and I can’t blame them, but from a baseball perspective it would be interesting.

So I don’t know what the plans are for baseball now. Are you going to play in a bubble like the NBA and the NHL has figured out how to play and try to control the environment? Are the playoffs then going to be controlled that way for baseball? I’m not up to speed on that. But it might be a good opportunity to try something like this crazy idea that Billy and I had, that seven straight games really proves your baseball mettle.

Are you talking to people about that? You have some standing.

Cal Ripken Jr.: I haven’t been, no! I’ll talk to my brother Billy, he’s at MLB Network, he can actually convey the message.

There is a lot of talk about younger people not being as interested in baseball. Baseball is a sport without a clock. Hockey has a clock, basketball is faster. There are more showboats, in the other sports. Do you have any ideas to quicken the game? Because the game can go on and on.

Cal Ripken Jr.: Well, I played in a minor game, which we played 32 innings in one night. We played the longest game in the history of professional baseball. It was a 33-inning game, and it played till 4:07 in the morning. The whole concept of the game being boring, it’s a mental game in many ways, it’s a cerebral game. There’s a lot of situations that change. There are things that happen all the way through, and I think the more you know about the game, the more you can be into what are happening all the time, it feels like it’s slow. There are probably some ways that you can increase the way the game is played, and that might start in the minor leagues where you encourage them not to walk around the mount, not so many meetings, because there’s a lot of stalling that happens in baseball.

Let’s talk about the future of baseball. This has been a particularly tough year (2020). In many ways baseball has been affected the hardest by COVID-19, and a season of 60 games, not 162 games. As a player, is it harder or easier without the fans? These games are now being played without anybody in the stands.

Cal Ripken Jr.: Well, I’m an optimistic person. So in some ways, instead of feeling sorry for yourself, saying, “Okay, we only get to play 60 games, and it’s without fans, let’s make the best of it. Let’s figure out, maybe there’s something we learned from this experience that can make the game better going forward. I don’t know what that is, but I will tell you the baseball game is magical when there are people in the stands. There’s no doubt about it. We really try hard, especially on the road — when it’s not hostile per se, but you’re not home — is that you try to perform, but there is an energy, and there’s a life that happens when you have people around. When you go to a restaurant, and a lot of the times, you want to be in a restaurant. It is about the quality of the food, but it’s also about the action and the people that are alive. We all are social and we all feed off each other. And to have that energy in the ballpark, I will tell you, the pressure situation is 100 times more pressure situation when you got people who care in that ballpark rooting one way or the other.

And yet you still want that pressure.

Cal Ripken Jr.: It’s the best thing in the world, and it’s the best feeling in the world if you’re able to come through in a moment like that and send the crowd into a tizzy. You know, one way or the other, it makes you feel like you’ve accomplished something. It’s a challenge, and that’s the magic of it all. Baseball is a great game, and these professionals are going to compete really hard, and trying to hit that 95-mile-an-hour fastball, it’s going to be important to whatever level. They’ll figure that out. And the quality of the competition will be good, but the magic of having people in the stands, you can’t replace that.

And your son is now in the same field?

Cal Ripken Jr.: He’s plugging along. He’s 27 years old, so this particular cancellation of the season hurts him a little bit. It’s a year of development that he’s missing. But he’s trying to find his way. He had a difficult start to his pro career where he was injured, lost a position in the organization, but then found it again with the Orioles, and last year he had a great year. And he was looking forward to continuing to develop as a player.

Were you worried that he would be put under pressure as your son, as you were being your father’s? “Oh, it’s the son of Cal Jr.”

Cal Ripken Jr.: It’s horrible in some ways. His last name, the expectations from when he was really small, people were looking for him to do great things all the time. I was able to develop and make mistakes, and learn from those mistakes without those expectations, but his expectations — at 11 years old all these teams would come over and go, “Okay, which one is he?” And they’d go, “Oh, he’s that.” And if he made an out or struck out, or did something, they would look to each other and go, “Ah, he’s not that good.” So my son felt that and felt like there was some sort of expectation. It couldn’t have been fun for him, but I give him a lot of credit that he pushed through. He was a heck of a basketball player, and he played basketball in high school. A good athlete and has got some super talent in baseball.

But you’re in a unique position because of your father and now your son, because this happens in many fields. It’s hard for kids to follow their parents because of the weight of expectations. What do you say to them about how to deal with that?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Well, I will tell you, I was very sensitive about it. And my mom might have been a little mad at me that I didn’t name my son after me. I was named after my dad, and it was almost like my mom thought it would be cool to give my name to my son.

So you’re Cal Jr. What did she want you to call him?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Cal Ripken the III. I had my daughter first. Rachel was born first, and if Rachel had been a boy, I might have done that. But then, after I had a chance to live life a little longer, and I started to think of the ramifications, and then hear stories from Brooks Robinson, or even read about Mickey Mantle, about naming their sons after them, it seemed to be an added burden that you placed on your son. I wanted my son to have his own identity.

The last name, being a little bit different of a last name, sometimes didn’t allow him to take the journey where he could find out fully about himself. But I want him to be him, whatever that is, whatever his passion is, wherever his talent carries him. Whatever he wants to do in life, no pressure from me, no expectations from me, he should do it. And I thought it would — I kept picturing roll call in school, where you call out the name to take the roll, and having my name repeated out loud, like, “Cal Ripken” and then everybody would turn around and kind of look.

Because you’re so famous in Baltimore, you’re an institution. People name their kids after you. They name their dogs after you. It would have been difficult for a little kid named Cal Ripken.

Cal Ripken Jr.: I try to keep things in perspective, which is probably one of the greatest things my parents gave me. Just because you can hit and throw doesn’t mean that you’re different. You should keep that in perspective. Everybody has their own talents, and everybody should earn their way and that sort of thing. So I always try to keep things in perspective, and perspective on fame. I wasn’t someone that wanted to pound my chest and say, “Look at me!” But because I was good in baseball and because I got attention and because people did name their dogs after me, and they knew my name, that was an issue. How was I supposed to deal with that? How was I going to deal with that with my own son, my own kids?

Sometimes I think it was a great burden to have the expectations created, and they had to deal with that in their own way. I could try to explain it to them, but I think one of the good things that I did was not give my son — he’s named Ryan Calvin, so he has, he has my first name, and I’m proud of that. But I tried to alleviate some of the burden and I try to explain to them, in real simple terms that they should maintain perspective.

There are some questions about the future of diversity in baseball.

Cal Ripken Jr.: I think one of the great things about baseball, when you look at the makeup of your team, many times, you find yourself in the back of a bus, you yourself in the back of a plane, and you look around, and there is people from all cultures. And now it has become a much more worldly game. So you can sit in the back of the bus and have somebody from Japan, from different parts of the world.

And the thing that we all have in common is that we can catch and throw and hit, and there’s a certain togetherness that happens from that. I think that’s the coolest part. And even from different backgrounds. You got people that live in the country, people that live in the city, people that had a good background where they were kind of rich, you had people that were kind of poor.

But it doesn’t matter when you’re on the plane, or you’re back on the bus, or when you’re playing out in the field, none of that stuff matters, which is the coolest thing in the world. I’m an envoy to the State Department to spread goodwill through sport. I’ve been to China, I’ve been to Nicaragua, I’ve been to the Czech Republic, I’ve been to Japan.

And you’re going to spread goodwill, and it’s the language of sport, and in particular for me, it’s the language of baseball, that whatever people are, you socially accept. There’s a trust that occurs that you’re sharing those. So whether — I don’t get into political goodwill, I guess, when you’re doing it for the State Department. But you are making friends through sport, and the trust is already there when you can relate in the course of baseball.

Do you think there are any efforts baseball could make to be more attractive to African American kids?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I know the challenge is now everybody is asked to specialize in a sport really early, instead of giving all people an opportunity to play and get an opportunity. So I think Major League Baseball is trying to expose to areas and give other people the opportunity. We have a foundation that I started after my dad. And we essentially use baseball, or sport, as an icebreaker to make friends. You start to match them with good mentors, and give them a different direction, and a positive outlet sometimes where you have some negative influences that are pulling on them. So we’ve had really great success going into place. But we’ve built those youth development parks that essentially to me are safe outdoor classrooms. We feel really good and it’s really interesting. I went into a club in D.C. one time, and sometimes you’re introducing baseball to a group of kids that hadn’t played baseball before, but they’re super athletic.

One of my favorite stories is there was this big guy that was kind of controlling the club from a leadership standpoint. There was a bunch of kids, but there was this one guy that pushed his way to the front of the line, and I’m throwing the ball to him, and he takes this big mighty swing and he can’t hit it. Then there’s this small little meek kid that comes in behind him, that’s very shy, I flipped the ball up to him and he has the hand-eye coordination to swing the bat and the ball jumps off his bat.

And to see the dynamic change, whereas the big kid is demanding, “I’m the leader, I get to tell you what to do” kind of thing in this environment, and then all the other kids want to go to the little kid and say, “How did you do that?” And the big kid kind of gets mad at the little kid for doing that. I just think that baseball is pretty magical in that way, and I know Major League Baseball is trying to expose baseball in all areas to give kids a chance to play.

You have very large hands. How many baseball gloves do you have? Did you get them custom made?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Yeah! One of the great things about being a big league player is that the equipment is really good, and you sign contracts, and yes, you can have as many gloves as you want.

How many do you have in your house?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Oh, I don’t know. The game gloves, I roughly went through a game glove and a half — one and a half — per year. So sometime around August I’d probably be changing the glove.

So you used the same one all year?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Pretty much.

Did you ever superstitiously say “I should keep that one” or “I should get rid of that” because I’m in a slump?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Well, sometimes I change gloves because there was one time Kirby Puckett hit me a ball in the Metro Dome, and I went to catch it, and it had so much topspin on it that it hit the palm of my glove and spun out, and I had an error on that play. And I kept thinking, “Okay, I got to change this glove out, because the spin off the turf, I got to have a glove that catches the ball as opposed to trapping the ball.” Like, sometimes on double plays you end up not closing the glove around the ball, you just catch it and throw.

So I took a different glove, which ironically when I changed my glove that time — whereas you catch the ball first, stop the spin, and then catch it and throw the ball to first base — that glove that I switched to was my practice glove and I really didn’t like it a whole lot. But I kept using it and that was the glove that I only made three errors in the whole season in one year. And I can’t tell you, that glove lasted me almost three years, that I used the game glove. Now, when you have a game glove, the way you wear your glove out is in practice. You’re taking hundreds of groundballs with another glove. So you’re wearing more practice gloves out than you wear out your game glove. So I always left my game glove for the game.

Do you keep your game gloves under glass somewhere?

Cal Ripken Jr.: No, not yet. I have them in a bunch of boxes. I found most of them.

So other people collect your autograph, and they collect baseball cards. Do you collect anything?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I’m a packrat and I haven’t thrown anything out! Anything that I had, including my Little League uniform, I still have. So one of my gloves, that’s my prized possession, and I’ve been looking for it, I think I put it in a special place, and now forgot where it is. But I’m sure I have it. Ronald Reagan threw out the first pitch in 1984. In 1983 we won the World Series. So opening day comes the next year, we’re playing the Chicago White Sox. He comes out to throw the first pitch out. The Secret Service comes to me and says, “Do you have a glove for the President to throw out the first pitch?” So I said, “Great!” So I gave him my backup gamer.

I gave it to the Secret Service and he threw out the first pitch. There were a couple of cool pictures that have the glove showing when he threw out the first pitch. So he would stay in the dugout for the first inning of the game. I hit in the first inning of the game and hit a homer in the first inning of the game. He was like the honorary manager. He made some sort of comment to me like, “You’re making me look good as the manager.” And he gave me the glove back after the home run.

And I said, “Mr. President, I would love it if you keep the glove.” And he said, “No, no, I can’t do that.” And I said, “Well if you give it back to me, you have to sign it.” I just said that. I don’t know where I got the courage that way. He took out a pen and he signed Ronald Reagan on the glove and gave it to me. So I have that glove in my possession. So that’s a little bit more meaningful. That was a backup gamer glove, but it’s still the glove that the President of the United States threw out the first pitch and he signed it.

I guess if I’m a collector, I’m a collector of that. But most of the other stuff is game stuff, bats, if I break a bat, if — I gave a lot of bats out to kids. You know, one of the fun part about when you break a bat sometimes, you’re coming out after a game, there’s a crowd of people there, you find the smallest kid that’s sitting there that is trying his way in and you single him out, and you give him your bat.

You got a call from Chief Justice John Roberts not too long ago.

Cal Ripken Jr.: Yeah. My wife is a judge. And she gets a call from the Chief Justice’s office in her chambers. You know, and to call him back, and she was thinking. “Gah! I wonder what they want?” There’s this special in-house musical celebration that they do for themselves. Ruth Bader Ginsburg has been in charge of it for 15 years or so. It’s sort of an internal celebration and Chief Justice Roberts always has themed remarks for that.

So in this particular theme, they were thinking about substitutions because one group cancelled on them at one point and then somebody else filled in for them, and Chief Justice Roberts is a pretty good sports fan, and he was thinking about the most famous substitution in the history of sports, or baseball, would be Wally Pipp substituted by Lou Gehrig and Wally Pipp losing his job.

So, they started to research that a little bit, and then they said, “Well, we have someone close by that actually broke that record, Cal Ripken, and he’s married to a judge, we probably could get him to come!” So that was the answer and the request, of course my wife —it was a great moment. She was really interested.

How many people were there?

Cal Ripken Jr.: I don’t know – 70, 80?

What did Justice Roberts talk about? Did he make a comparison between you and Justice Ginsburg?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Well, he’s a fantastic speaker, and the theme of this speech, and I was sitting there in awe, just listening to him, but basically he made the comparison that “Cal was there. There’s eight other people on Cal’s team and he was there for each one of the eight each and every day, making it easier for them. He’s the Iron Man of baseball, but we have the Iron Woman of the Supreme Court who makes us other eight that much better each and every day. So it was a wonderful tribute. And I remember, I had to stay back and it was a surprise, and then he made those remarks, and he says, “Then we have Cal Ripken here,” so I stood up, “And I think it’s only appropriate that the Iron Man of baseball meet the Iron Woman of the Supreme Court.”

When you hear today about so many highly paid athletes say, “I don’t feel good. I don’t want to play today.” It’s a different game, right? What do you think of that?

Cal Ripken Jr.: Are you asking me do I sit in judgment of them when they don’t play 162 games? No, I don’t sit in judgment. And you can never say a question if somebody is injured or not, because if they’re injured, or they say their muscles are tighter for that, or they need a physical break, you have to assume that that’s true. I will tell you that I am proud of my influence as an “every day” player. There’s been some players that come to be teammates of mine that go on and push themselves to play 162, and maybe it’s just for one year, but there were two guys: Brady Anderson and B.J. Surhoff, that pushed themselves to play the 162, and had the best years of their career.

And I’ve heard other players say they feel like they can’t take a day off, or they can’t ask for a day off in my presence, and in some ways, I think that’s a positive influence. But I don’t sit in judgment of anyone. I think, in this day and age, they’re looking at, “Let me get the best 145 games out of my player,” as opposed to the 162. Maybe you’re not looking at it from the intangible values of playing every day and the challenges.

Because the playoffs can be determined even more so by one game. One game can determine whether you make the playoffs or not, out of 162, and you don’t know which game that is. I played in my rookie year — 1982 — I ended up playing 160 games. I think I missed one game because I got hit in the coconut, and I think I missed one because I had a temperature of 104 or something in Chicago, but that was early in the season.

But as the season went on, we came into game 162 tied evenly with the Milwaukee Brewers. So the playoffs were determined, the winner was determined on the last day of the season. We end up losing to the Milwaukee Brewers, they went on to play in the World Series in that particular year. And we all sat down through the course of the wintertime and tried to remember a game we should have won. Or where could we have made that one game up? And that’s the idea of playing every day, too, is you don’t know how the end of the season is going to end up, and you don’t want to put yourself in a position to go back and say, “I wish I would have played this game” or “I wish I would have played that game” or “I wish I didn’t take that off, maybe I could have helped us win in that way.” So I don’t sit in judgment, but I do like people to understand the importance and the significance of each and every game.

Do you think that what you were able to do, game after game, in showing up, will be as valued in the future?

Cal Ripken Jr.: It’s a principle and it is a value. It is something that people really care about, and I can tell you that, because we’re going to celebrate. September 6th (2020) will be the 25th anniversary of that night. That happened September 6th, 1995, and it’s already been 25 years. One of the greatest things that I was able to experience during that celebration was the lead-up, that everybody else shared their streak with me.

You know, I haven’t missed a day of work in 31 years. From the first day of school to the end, I had perfect attendance. There’s a value that everybody understands in their own life: the importance of showing up and committing to something. I thought particularly it was good, Ernie Tyler had worked at the stadium. At the time, he was an umpire attendant, he took care of the umpires, did the balls behind home plate. He hadn’t missed a home game in 31 years. He voluntarily ended his streak by coming to my Hall of Fame ceremony, which was a really good tribute and a good honor.

But it’s amazing. It’s important to people to show up. It’s important people to commit to that. And so the joy was to hear all the different stories, and what was important to them and how they haven’t missed a day? You find out, a lot of times when the going gets tough, sometimes people disappear — whether it’s in business, whether it’s on the team — when you really need to have them show up, they’re not there. So I think people take great pride, no matter what happens — good or bad, rain or shine — I’m going to be there. And I think that most people think that is a good trait.

We agree. Thank you so much for your example and for speaking with us today.