Life is a competitive endeavor. And there's nothing more competitive, obviously, than combat.

David Petraeus was born and raised in Cornwall, New York, a few miles up the Hudson River from the United States Military Academy at West Point. His mother was a librarian; his father was a Dutch sea captain who had fled the German occupation of the Netherlands in World War II. After the war, Petraeus senior worked in a power plant. A great emphasis was placed on both academics and athletics in the Petraeus household, and David Petraeus excelled in both.

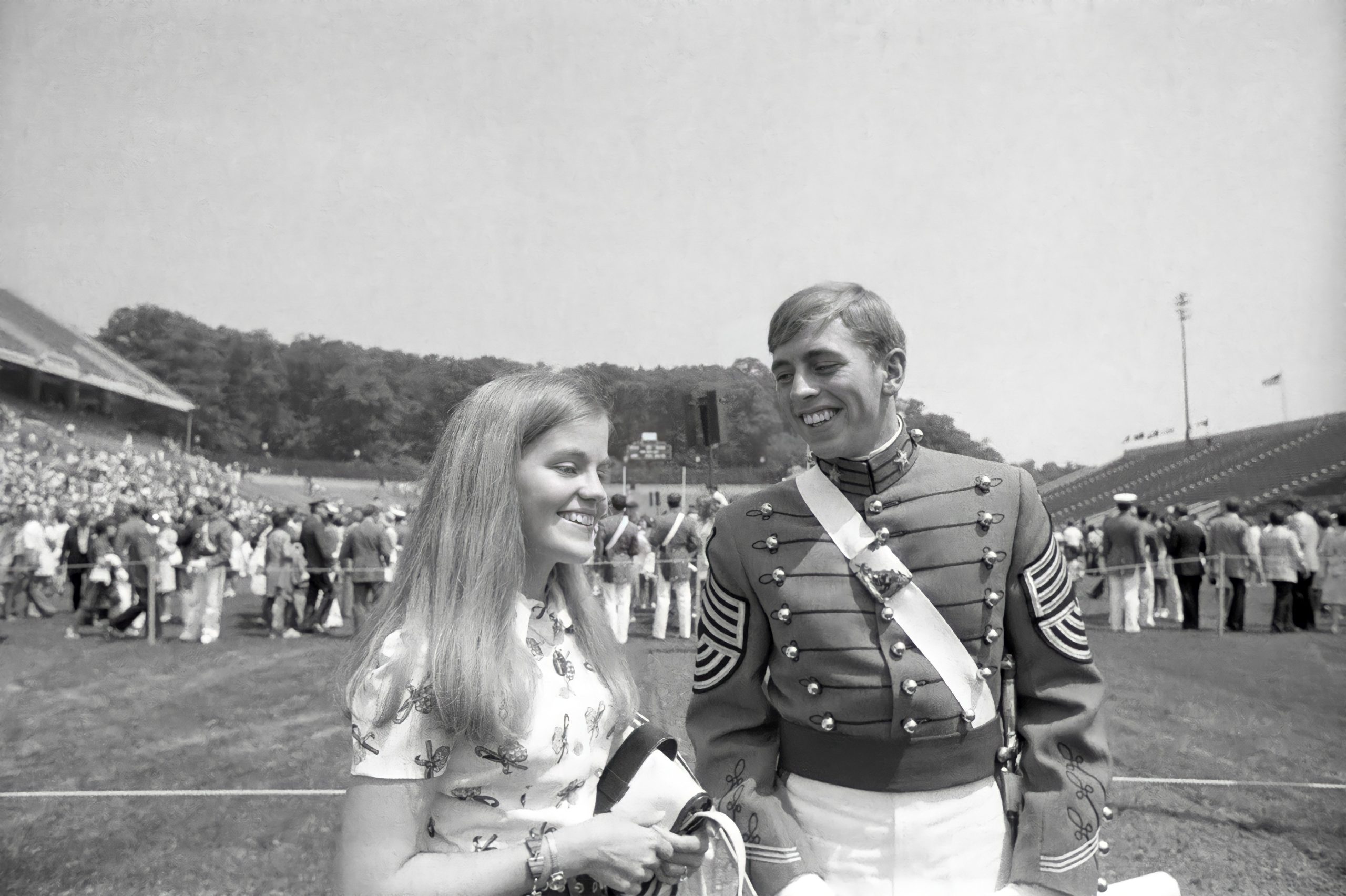

The influence of West Point was strongly felt in the community, and although he was accepted at other colleges, when he won a coveted appointment to West Point, David Petraeus gladly joined the United States Corps of Cadets. He continued to excel at West Point, following the demanding pre-med curriculum and competing in soccer and downhill skiing. Although he did well in his science courses, by his senior year he realized he did not have a calling for medicine and sought commission as an infantry officer. He graduated in the top five percent of his class and received his commission as a second lieutenant in the United States Army. Shortly after graduation, he married Holly Knowlton, the daughter of General William Knowlton, Superintendent of the Military Academy. The couple would raise a son and a daughter while meeting all the challenges and upheavals of a career in the military.

After leaving West Point, David Petraeus continued to distinguish himself as a soldier and scholar. He was first in his class at the physically grueling Army Ranger School, where he won all three of the top awards, including the William O. Darby Award, named for the officer who led the first unit of Army Rangers during World War II. Petraeus spent most of the next decade serving in infantry and mechanized units in the U.S. and Europe, and received the first of many promotions.

He was first in his class again at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, and subsequently earned MPA and Ph.D. degrees in International Relations from the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University. While writing his dissertation on “The American Military and the Lessons of Vietnam,” he returned to West Point as Assistant Professor of International Relations.

Petraeus honed his administrative skills in a series of staff positions. He served as military assistant to General John Galvin, the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe (SACEUR), as assistant executive officer to General Carlo Vuono, the Army Chief of Staff, and as executive assistant to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Hugh Shelton. Over the course of these assignments, he rose from lieutenant colonel to brigadier general.

In his 37 years in the Army, Petraeus held leadership positions in airborne, mechanized, and air assault infantry units in Europe, the United States, and the Middle East. He acquired invaluable expertise in the arts of post-conflict reconstruction, serving as Chief of Operations of the United Nations Force in Haiti, and Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations of the NATO Stabilization Force in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

In 2003, Petraeus, now a major general, commanded the 101st Airborne Division in the assault on Baghdad. This campaign was recounted by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Rick Atkinson in his book In the Company of Soldiers. Tasked with the occupation and pacification of the Iraqi city of Mosul after the collapse of the Iraqi regular forces, General Petraeus set the standard for executing successful counterinsurgency operations: restoring security, building a local security force, rebuilding the city’s university and other institutions, and organizing the region’s first free elections. Promoted to lieutenant general, he was given command of the multinational Security Transition Command Iraq. In 15 months, his command executed a massive reconstruction project, and trained and equipped 100,000 Iraq Security Forces, the largest operation of its kind since World War II. During this period, Petraeus published articles in the military and civilian press sharing the insights he had gained in counterinsurgency and reconstruction.

After returning to the United States, General Petraeus was appointed Commanding General at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where he also oversaw the Command and General Staff College. At Leavenworth, Petraeus and Marine General James Mattis assembled an unprecedented team of experts from military officers, scholars, journalists and human rights advocates to research and compile a new army field manual for counterinsurgency operations, 3-24: Counterinsurgency. After integrating the new material into staff training and field operations, Petraeus refined the essentials of the new teaching in his landmark treatise Commander’s Counterinsurgency Guidance, now studied around the world.

In 2007, deteriorating conditions in Iraq called for a change in strategy, and President George W. Bush chose General Petraeus to lead a renewed effort, designated “the Surge.” The president, with the Senate’s unanimous approval, promoted Petraeus to four-star general and named him commander of the Multi-National Force Iraq. The year that followed saw a marked reduction in sectarian violence and in attacks on U.S. personnel. Professional Iraqi security forces took the place of irregular Shiite militias in Baghdad, while tribal leaders in Sunni-dominated areas turned against Al-Qaeda terrorists who had attempted to build bases there. Petraeus’s skillful turnaround of an apparently hopeless situation made him the most admired leader in the United States military, one who enjoyed enthusiastic support from political leaders of both parties. His awards and decorations include four awards of the Defense Distinguished Service Medal, three awards of the Distinguished Service Medal, the Bronze Star Medal for valor, and the State Department Distinguished Service Award.

He assumed leadership of the United States Central Command in 2008, taking responsibility for all U.S. military operations in the Middle East, until President Barack Obama tapped him to directly lead U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan. With the end of the U.S. combat role in Iraq and the winding down of military involvement in Afghanistan, President Obama called on Petraeus to serve in a civilian capacity for the first time. After 37 years of uniformed service, General Petraeus retired from the U.S. Army, and with the unanimous approval of the United States Senate, assumed duties as the 20th Director of the Central Intelligence Agency. As CIA Director, General Petraeus was responsible for human intelligence, covert operations, counterintelligence, relations with foreign intelligence services, and open source collection programs on behalf of the entire intelligence community and the U.S. government. In November 2012, Petraeus admitted to an extramarital affair with a female journalist, and resigned his position at the CIA. Petraeus publicly shared his disappointment in his own private conduct, but by resigning immediately, he spared the agency and the nation the embarrassment and distraction of a prolonged scandal. After leaving office, he pled guilty to a misdemeanor charge of mishandling classified information in connection with the affair.

Since leaving public life, David Petraeus has accepted a visiting professorship at the Macaulay Honors College of the City University of New York and an endowed professorship at the University of Southern California. He is also a non-resident Senior Fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. A partner at the investment firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. L.P., he chairs the firm’s KKR Global Institute, which researches investment opportunities in new locations.

Today, David and Holly Petraeus maintain homes in Northern Virginia and Springfield, New Hampshire. Their son, Stephen, is a United States Army officer who has served with an airborne infantry combat team in Afghanistan. The tradition of military service runs strong in the Petraeus family.

Holly Petraeus is not only the daughter, wife, sister, and mother of U.S. army officers; her grandfather and great-grandfather also served. She has made a personal cause of assuring that military families are fairly treated by their nation’s financial services industry. She taught financial education classes for many years to service members and their families.

After serving as director of the federal government’s Better Business Bureau Military Line, Holly Petraeus accepted an appointment by President Obama in 2011 to direct the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s Office of Servicemember Affairs. Her office promotes financial education and combats the predatory lending practices that pose a special risk to military families. In addition to his professional and academic commitments, David Petraeus serves on the boards of numerous nonprofits, including American Corporate Partners, which connects Iraq and Afghanistan veterans to business professionals for career guidance.

Hailed as the “the world’s leading expert in counterinsurgency warfare,” General David Petraeus capped a brilliant career in the United States Army by leading the campaigns that turned the tide of battle in both Iraq and Afghanistan.

A graduate of West Point with a doctorate from Princeton, Petraeus held leadership positions in airborne, mechanized, and air assault infantry units in Europe, the United States, and the Middle East. When President George W. Bush decided to change strategy in Iraq, he chose General Petraeus to lead the surge, turning around a seemingly hopeless situation. President Barack Obama called on him to lead U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan.

After 37 years of uniformed service, General Petraeus won the unanimous approval of the United States Senate to become the 20th Director of the Central Intelligence Agency. Now retired from public life, he remains a sought-after authority on strategic leadership.

What do you think President Bush saw in you that caused him to pluck you out of the chain of command to lead the Surge in Iraq?

David Petraeus: I’d only met him a few times at that point in time. I hosted him for a full day at Fort Campbell, Kentucky when I was a two-star, after I came home from the first year in Iraq as the commander of the 101st Airborne Division for the fight to Baghdad, and then the subsequent beginning of the counterinsurgency campaign in Mosul. Indeed, I’d like to think our division had some unique approaches, but they didn’t all survive, unfortunately. The reconciliation issue in particular was not supported in Baghdad, and it was reversed after we left.

But you did have some success, at least for a time.

David Petraeus: We had some pretty good period there, and it was seen as an area that, I guess, was what “right” looks like, if you will. He came out to see us and that was a wonderful day, actually. I was really impressed by the President and the amount of time that he spent. I think we’d probably lost 60 soldiers at that point at Fort Campbell, not just in the 101st, but some also in the 160 Special Ops Aviation, Special Forces Group. The family members of each of those soldiers were positioned all the way around in the museum at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. He spent a full five minutes, I think, with every single one of them. He was so far off schedule it wasn’t funny. I was sent back, of course, fairly soon actually after getting home, to establish the so-called “Train and Equip” mission to try to develop, train — really recruit, train, equip — develop all the forces of the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Defense, including the ministries themselves ultimately. Not to mention building all the infrastructure that they need and all the doctrine, every piece of a modern military and, again, police force in all respects. It was a gargantuan task. That was a 15-and-a-half month tour. I had actually been sent back to do an assessment of the Iraqi Security Forces shortly after I got home as a two-star. I came back and reported to Secretary Rumsfeld. Then essentially his reward for that was, “Okay, go over there and implement what it is you say you need to do.” So we did, and we made a great deal of progress, although this was an effort — it was truly Sisyphean in some respects, and it really was pushing a stone up the hill.

He did know that we had written the Counterinsurgency Field Manual while I was at Leavenworth after coming back. He (President Bush) called me in after I came back as a three-star. I remember I gave him some fairly frank assessments and I’d written something up. I hadn’t cleared it with the Secretary or the Chairman. And you know, I’m just a three-star at this point, and you got all the National Security team there in the Oval Office. But then he starts asking, “So what are your takeaways? What are your conclusions? What about this guy? What about that guy?” And it was a wonderful conversation. Perhaps he remembered that later on. I think he actually took me out and did a Rose Garden (event) saying thank you, or maybe in the Oval Office as well. But the truth is, what happened I think is, as the situation in Iraq spiraled downward so seriously — in 2006 in particular, after the bombing of this very sacred Shia shrine north of Baghdad, it just unleashed sectarian violence between Shia and Sunni, and it played — and Al Qaeda wanted that to happen. They wanted to be a catalyst for civil war, frankly, to tear the country apart. It was very, very serious. He had different individuals in to advise him. They did not always agree on the way forward, frankly. Some said there should be a surge. Others said you should hand it off quicker and get out. Others said put more Special Forces in, that’ll solve it. But apparently, they typically agreed that what he also should do is actually send me over there, back over there. So that’s what happened, obviously. I remember going to see him after we had the confirmation hearing, and I think I gave him a signed copy of the Counterinsurgency Field Manual. I said, “Well, this is what we’re going to implement.” And he said, “Yeah, yeah.” And he said, “I guess we’re doubling down, General.” And I said, “Mr. President, we’re not ‘doubling down’ in the military. We’re going ‘all in,’ and we need all the rest of the government to go all in as well.” And he really pushed that.

He had such unbelievable focus on the effort in Iraq. The week in Washington, every Monday morning, began at 7:30 with the entire National Security Team around the Situation Room table, the President at the head and Ambassador Ryan Crocker and me on a video teleconference, for an entire hour. It started promptly on time. It ended on time. It was all dialogue between him and us, and occasionally someone else could chime in. It was not asking the people around the table how they thought it was going. It was going directly to the two of us that were most charged now. They had the Central Command Commander would be on video teleconference, and of course the Chairman and the Secretary and the Secretary of State and others were all there. But again, it was dialogue between the three of us generally, and it was quite an extraordinary degree of focus. In fact, then the Secretary of Defense would have one with me the next day. And then most weeks, Prime Minister Maliki had one with the President that Ambassador Crocker and I would also attend. So there was a huge amount of focus from the White House, from the President, and that obviously galvanized all of the Executive Branch to try to do as much as they could to retrieve what was a very, very desperate situation.

There was a sense of fearlessness about what you were proposing with the Surge in Iraq, a very dramatic change in strategy. Can you talk about those ideas and changes?

David Petraeus: Maybe here I should talk about strategic leadership because, arguably, I’d done strategic leadership before. But this is really strategic leadership. A definition of strategic leadership would be that you are leading a very large organization, and you are the one charting the course for it. You have quite a degree of latitude. So this is a CEO kind of position. We ultimately had 165,000 Americans on the ground there, almost that number of contractors, and many more on aircraft carriers, or in bases in the Gulf states supporting us as well. So it was an enormous effort.

A strategic leader has four tasks, in my view. The first is to get the big ideas right. As I mentioned earlier, those don’t come easy. It has to be the result of a lot of thinking, inclusive discussions, seminars, conferences, whatever it may be. But you’ve got to get them right. If you don’t get them right, if you don’t get the strategy right, all else is for naught here. Everything else you’re building then is on a foundation of sand. The second task is to communicate those big ideas effectively throughout the breadth and depth of the organization. And you do this in every way possible. The third task is to oversee the implementation of them, because of course, you’re not the one implementing them directly. That’s many levels below you. But you certainly have to go out and see for yourself. You have to have metrics. You have to have a battle rhythm. You have to have a whole series of tasks that you perform yourself, campaign plan reviews and on and on. It’s quite exhaustive. And then the fourth task is you have to identify how those big ideas need to be refined. It’s the process of identifying lessons, if you will. But lessons aren’t learned until they’re actually incorporated in the documents, the campaign plan, the policies, the procedures, the SOPs — whatever — that are the mechanism for conveying the big ideas. In Iraq, the big ideas were, in most cases, a complete shift from what it was that we were doing before. The biggest of the big ideas was that the human train was a decisive train, i.e., the people are the prize. You have to secure the people. And you can only secure the people by living with them, by locating your bases where they live in their neighborhood. So at a time when we were retreating to big bases, concentrating all our forces on big bases and going out and driving around a few times a day and then be back at the big base to handoff quicker to the Iraqis, we reversed that. We ultimately established, for example, we had to fight for and establish 77 additional locations at which our troopers were located — together with Iraqis typically — 77 just in the Greater Baghdad divisional area.

Another idea concerned the handoff to the Iraqis. I stopped the transition to the Iraqis. They could not handle the level of violence. In fact, their units had deteriorated. Not only had they not gotten better, they had actually gone downhill as violence had gone up. So we stopped the transition to them. In some cases, we reversed it. We took units offline. We had the government replace commanders wholesale in many cases. We had to take every one of the brigades of the two police divisions offline, one after the other, and go through a 30-day retraining program and going back into the fight.

The third big idea was that you can’t kill or capture your way out of an industrial strength insurgency, and that’s what we faced. Ultimately, we reconciled with some 80- to 85,000 Sunni insurgents alone, just to give you a sense of the scale. And some 25,000 Shia militia extremists as well. This is industrial strength. We’d been killing or capturing every night. Joint Special Operations Command — Admiral McRaven’s force subsequently, it was General McChrystal at the time — they were doing ten to 15 operations a night, and the situation in some of the areas was getting worse, not better. So it’s not enough to go out and do kinetic operations. What you have to do is persuade as many as possible of those who are part of the problem to become part of the solution, to give them an incentive to support the new Iraq, rather than to continue to oppose. And we did. And that was reconciliation, ultimately was “the Awakening.” Sunni Arabs decided that they would throw off Al Qaeda if we could secure them, to be sure. Then they joined in and helped the security. Then we got them incorporated as “Sons of Iraq” and all the rest. But this was, again, a huge change. There was a tiny bit of reconciliation that was going on, but it wasn’t developing at all the way it was. I made my first trip to see that, in fact, within three days of taking command. And I said, “This is what we’re going to do and let’s get on with it.”

You have irreconcilables. You can identify them now even more than before. So General McChrystal’s Joint Special Operations Command or counterterrorist forces — later Admiral McRaven’s — they amped up their operations even more. Then we had detainees. We had, when I took command, probably 18- to 19,000 detainees, and we were releasing them because of pressure from the Iraqi government. And I said, “Stop! We are not going to release any more detainees until we have a program for rehabilitating them, for preparing them to go back into society. But we can’t even do that until we identify who the hardcore detainees are who are corrupting all the others and who have turned our detention facilities into a terrorist training university.” So we stopped that. Huge pressure from the Iraqi government, who wanted their sons back, regardless of what they’d done, the tribes at least. And it ultimately was 27,000 before we started actually the process. But we had a review process, rehabilitation, job training, basic skills and a variety of other tasks. But we had to go into these enclosures and find the most extreme, pull them out. By the way, you do that unarmed, because you never take a weapon into a detention facility. These are open. There’s 700 to 800 detainees in one of these enclosures. All very humane, very good food, health care and everything else, but very, very challenging mission for our military police.

I changed the mission statement, and the first piece of our campaign plan within that first week. I knew what I needed to do. I didn’t need to go through a process of — you know, I’d been in Iraq for two-and-a-half years at that point in time and had studied it when I was not there and worked out these ideas for counterinsurgency. And I started communicating them — the second task — the very first day, right after taking the colors, if you will, and becoming the commander in your first change of command remarks. And that’s where the focus is, on securing the people. It can only be done by living with them, not by consolidating on big bases. Then I gathered the commanders together who were at the change of command, of course, and talked to them about what we were going to do. Put out a letter to all of our troopers on the very first day — the soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, Coast Guardsmen, and civilians of Multi-National Force Iraq. It went on and on from there. Then, ultimately, we revised the whole campaign plan and et cetera and et cetera. Then the overseeing the implementation. We had to work metrics very hard. It took six months before I was willing to actually release how we reached the metrics, how we arrived at them, what were the definitions of the terms and all the rest of that. To sit down with The New York Times, The Washington Post, the major networks, and go through them, so you can tell “Are we winning or are we losing?” “Are we making progress…” is a better way actually of saying it, “… or are we not?” Because I don’t think you win these kinds of endeavors.

There’s no taking the hill, planting the flag, and going home to a victory parade. Rather, you drive the level of violence down. But you have to maintain focus. And, in fact, tragically, we saw what happened when that focus was not maintained over the past two-and-a-half or so years. Unfortunately, Prime Minister Maliki undid a lot of what we’d done together to bring the fabric of society back together, Sunni back with Shia, by going after Sunni political figures, by putting down peaceful demonstrations very violently, and essentially giving the Sunni Arabs once again a stake in the failure of the new Iraq, rather than a stake in its success. And then we had a formal “lessons learned” process. We had the Center for Army Lessons Learned teams with our units. We had the Asymmetric Warfare Group, very formal, special operators and serving special operators out with units. We had the Joint Lessons Learned team. And every time I sat down with our commanders, whenever we had a commanders’ conference as part of overseeing the implementation, or a campaign plan review quarterly with the ambassador as well, we’d go through — everybody had to identify one or two lessons or best practices that were applicable to all. And then we’d work on actually tracking. Because again, a lesson isn’t learned when it’s identified. I actually used to joke and say the Center for Army Lessons Learned should be renamed. It should be the Center for Army Lessons Identified, because it’s not learned until they’re put into the doctrinal manuals, the instruction to our leaders, the collective training exercises or combat, whatever it may be.