I come from a musical family. My father was the director of music at the London College of Music...my mother was a piano teacher...my brother, of course, was a leading concert cellist. And so the family was all music. But I was the one who brought rock, pop, and, of course, theater into my family.

Andrew Lloyd Webber, a name synonymous with musical theater, has had a career that spans over half a century. His compositions, which include some of the world’s most famous and beloved musicals, have earned him numerous awards and accolades.

Indeed, his genius has transformed the world of musical theater, making him a titan in the industry and a household name across the globe. However, the journey to becoming a musical theater legend began in a humble home in London, where a young Andrew found his passion for music. Andrew was born on March 22, 1948, in Kensington, London to a highly musical family. His father, William Lloyd Webber, was the director of music at the London College of Music, a senior lecturer in music composition at the Royal College of Music, and a famous organist.

His mother, Jean Johnstone, was a piano teacher specializing in teaching very young children. Additionally, his brother, Julian, was a leading concert cellist and a prominent pianist. Clearly, music was always present in Lloyd Webber’s life and formed an essential part of his upbringing. However, despite his family’s inclination towards classical music, Lloyd Webber was the one who introduced rock, pop, and theater into his family. He was exposed to musicals and opera from a very young age, thanks to an aunt who was an actress. This exposure ignited a passion for theater and musical theater in him by the time he was seven or eight years old. From these humble beginnings, Lloyd Webber would go on to create masterpieces that would captivate audiences for generations, solidifying his legacy as one of the greatest composers in the history of musical theater.

One of Lloyd Webber’s earliest memories of composing music dates back to when he was around eight years old. His father arranged for some of his juvenile tunes to be published in a magazine called Music Teacher. While he does not recall exactly when he composed his first piece, he remembers recognizing a small part of one of those early tunes in ‘Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat,’ which he wrote when he was 18 or 19. Clearly, his passion for composing started at a very young age. He also enjoyed writing for the theater almost immediately, creating his own toy theater and producing what he calls ‘dreadful musicals’ with his brother and some friends. Lloyd Webber’s parents were very supportive of his musical pursuits, even when he decided to take a different path than what they might have expected. He was awarded a demi-ship to Magdalen College, Oxford, in History, but after meeting Tim Rice, he decided not to take it up. This decision was initially seen as odd by his family, but his father understood and supported his desire to follow his own path. Lloyd Webber was only 17 at the time and was aware of his talent for composing melodies.

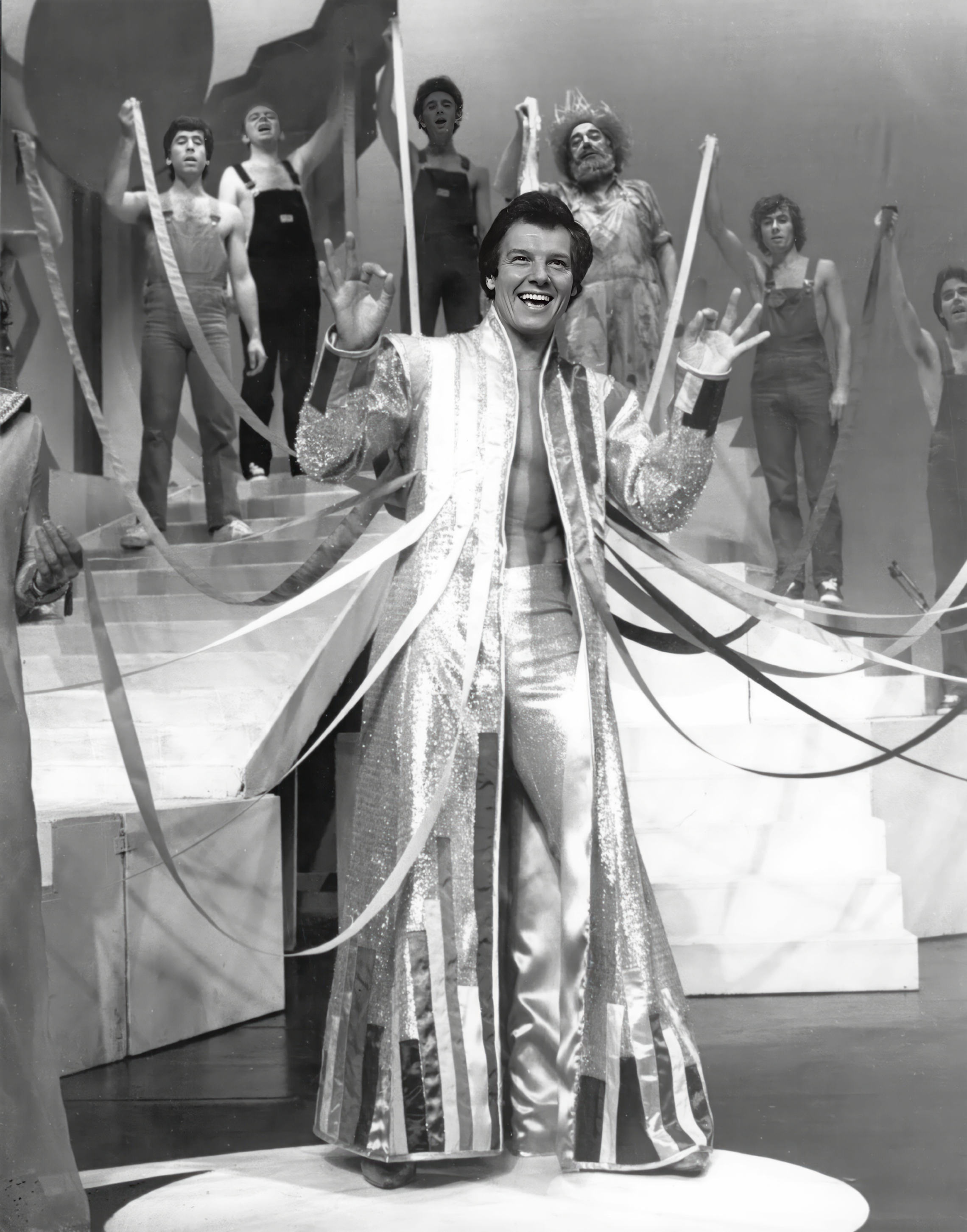

The late 1960s marked the beginning of a spectacular journey for Lloyd Webber when he crossed paths with lyricist Tim Rice. Their first venture was a musical adaptation of “The Likes of Us,” which, interestingly, didn’t see the light of day until 2005. However, it was their subsequent project, Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, a fresh take on the biblical story of Joseph, that catapulted them into international stardom. Initially crafted for a school concert, the musical’s overwhelming success propelled it into a more grandiose production, earning them accolades worldwide. This early masterpiece illustrated Lloyd Webber’s remarkable knack for amalgamating diverse musical styles, resulting in a piece that captivated audiences of all ages.

The musical, a cornucopia of musical styles, not only marked the dawn of a prosperous collaboration between Lloyd Webber and Rice but also injected a new, innovative spirit into musical theater. The contemporary interpretation of a biblical narrative coupled with a rich tapestry of musical styles made it an irresistible draw for a wide audience. The triumph of the musical, coupled with its enduring popularity, underscores its lasting resonance and influence in the theater realm. Lloyd Webber’s groundbreaking approach in Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat was a precursor to a career characterized by ingenuity and magnificence. This trailblazing work by Lloyd Webber set the stage for a glittering career that would continually push the boundaries of musical theater.

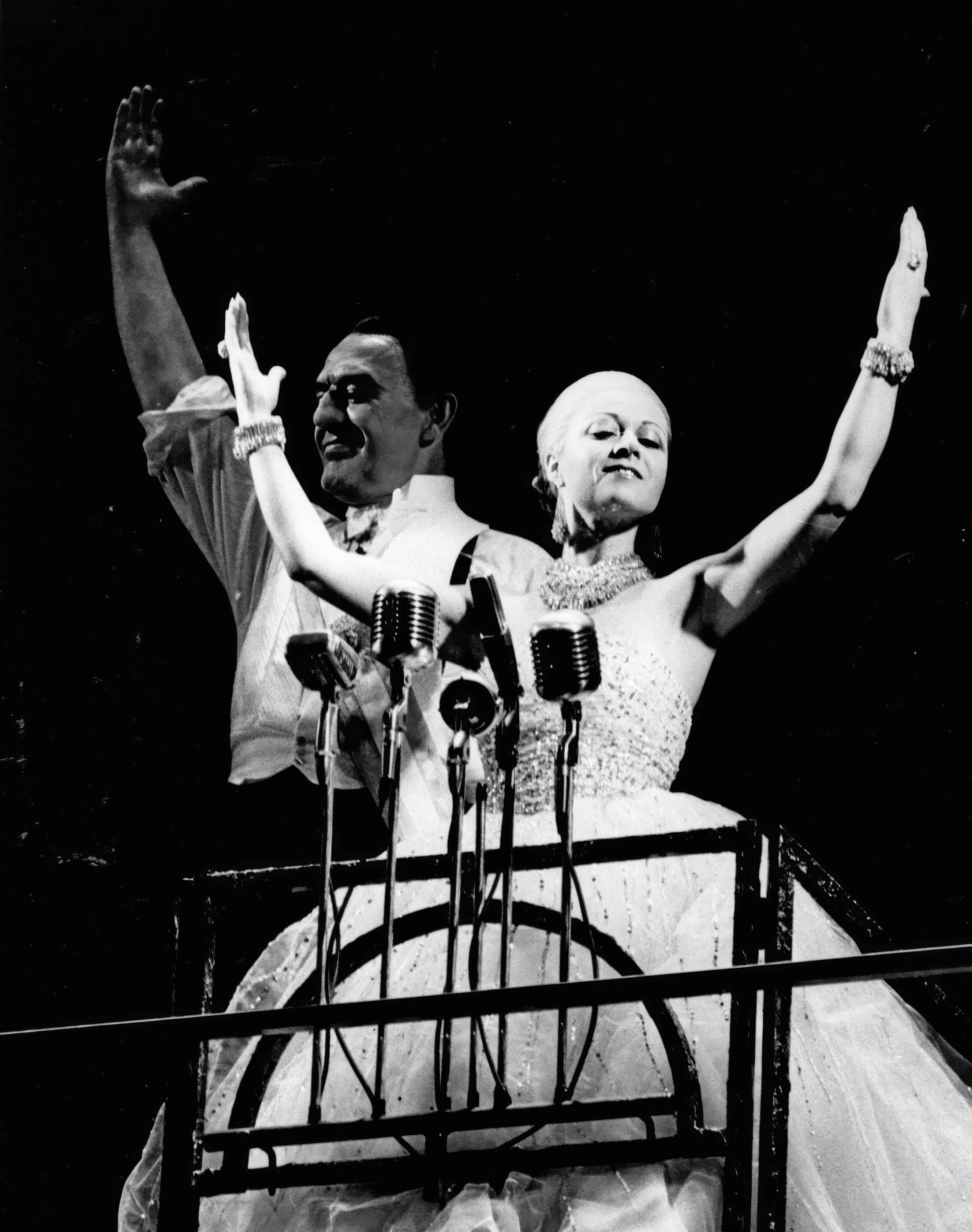

Lloyd Webber carried on this streak of success throughout the 1970s and 1980s. A groundbreaking moment came in 1976 with ‘Evita,’ a revolutionary musical chronicling the life of Argentinian First Lady Eva Perón. It not only explored political themes but also showcased a formidable female lead, a testament to Lloyd Webber’s forward-thinking and innovative spirit. Hit songs like “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” and “Another Suitcase in Another Hall” propelled Lloyd Webber into the stratosphere as a musical theater luminary. ‘Evita’ demonstrated his genius for intertwining the personal and political, resulting in a musical that also served as a potent reflection on a crucial historical period. In the late 1970s, Webber began setting T.S. Elliot’s collection of poems to music, which later resulted in the musical Cats. The musical opened on the West End in 1981 and ran for 21 years before closing. It set records as the longest-running musical in both London and Broadway, a feat only surpassed by another Lloyd Webber masterpiece, The Phantom of the Opera. This achievement underscored the enduring allure of Lloyd Webber’s creations and his unmatched influence in the world of theater. Furthermore, despite negative reviews from critics for his 1984 Starlight Express, the musical defied expectations, becoming one of the West End’s longest-running musicals. This resilience illustrated Lloyd Webber’s remarkable ability to captivate audiences, even when faced with industry pushback.

1986 marked a monumental year for Lloyd Webber with the premiere of ‘The Phantom of the Opera’ at Her Majesty’s Theatre in the West End. Drawing inspiration from Gaston Leroux’s 1911 novel, he tailored the role of Christine for his then-wife, Sarah Brightman. She dazzled in the original London and Broadway productions, sharing the stage with Michael Crawford, who portrayed the Phantom. Directed by the esteemed Harold Prince, who also helmed Evita, and featuring lyrics by Charles Hart and additional material by Richard Stilgoe, with whom Lloyd Webber collaborated on the book of the musical, The Phantom of the Opera was destined for greatness. Its phenomenal success, with a record-breaking run in the West End and, until April 2023, on Broadway, solidifies its status as a cultural force. A staggering 13,981 performances made it the longest-running show in Broadway history, a triumph that underscores Lloyd Webber’s genius in crafting narratives that deeply resonate with audiences across the globe.

The enchanting love story, the intricately designed costumes, and the unforgettable songs like “The Music of the Night,” “All I Ask of You,” and the iconic title track, “The Phantom of the Opera,” have made it a beloved masterpiece worldwide. This global adoration further solidified Lloyd Webber’s position as a musical virtuoso, a genius whose creations have left an indelible mark on the fabric of musical theater. Reflecting on the musical’s romantic theme, he shared in an interview, “Phantom of the Opera was the first out and out romantic musical I wrote…I think people do in the end love a great romance. Funny enough the Phantom of the Opera is a very good story.” This insightful comment sheds light on the secret sauce of his astronomical success – an innate understanding of the human experience and the universal themes that unite us all.

Following “The Phantom of the Opera,” Lloyd Webber continued to work on several other projects including Aspects of Love (1989), Sunset Boulevard (1993), and a film version of Cats (1998). He was named a recipient of the Kennedy Center Honors in 2006 and, in 2016, a revival of Sunset Boulevard was staged at the London Coliseum, which then transferred to Broadway in 2017.

In 2018, Lloyd Webber published his memoir, Unmasked, and won an Emmy for Jesus Christ Superstar Live in Concert, making him one of the few people to have won an Academy, Emmy, Grammy, and Tony Award. Several of his songs, including “Memory” from Cats, “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” from Jesus Christ Superstar, and “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” from Evita, have been widely recorded and successful outside of their parent musicals.

Lloyd Webber’s stunning array of accolades underscore his monumental contribution to the arts. From receiving a knighthood in 1992, a peerage for services to the arts, six Tonys, three Grammys (including the Grammy Legend Award), an Academy Award, 14 Ivor Novello Awards, seven Olivier Awards, a Golden Globe, a Brit Award, to the 2006 Kennedy Center Honors, and the 2008 Classic Brit Award for Outstanding Contribution to Music, each honor signifies a moment in his journey of genius and his immeasurable impact on musical theater and beyond. Furthermore, his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, induction into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, and fellowship of the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers, and Authors, are all physical manifestations of a legacy that has touched hearts worldwide.

His journey, marked by resilience, adaptation, and an endless well of creativity, is nothing short of awe-inspiring. Since his early years, Lloyd Webber has captivated global audiences with his exceptional storytelling, music, and artistry, demonstrating an insatiable drive to create and innovate.

His masterpieces, which have not only withstood the test of time but have also managed to bridge generational and cultural differences, bear testament to the universal power of art, music, and storytelling. The global appeal and enduring popularity of his creations underline the profound impact that one individual can have in shaping and elevating an entire art form. His legacy, therefore, extends beyond being a composer; he is a luminary who has illuminated the world with the boundless possibilities of human creativity.

This multifaceted genius, with his uncanny ability to tap into the collective consciousness, has not only transformed musical theater but has also shown us the power of art to connect, heal, and inspire. In a world often divided by differences, Andrew Lloyd Webber’s body of work stands as a unifying force, a testament to the transcendent power of music and storytelling. His enduring success and influence are not just a celebration of his individual genius but a reminder of the indelible impact that art, in all its forms, can have on humanity.

Sunset Boulevard is back on Broadway in 2024, reimagined by director Jamie Lloyd in a scorching new revival. Starring Nicole Scherzinger as Norma Desmond, this production has been hailed as one of the most exhilarating in years, breathing fresh life into Andrew Lloyd Webber’s timeless classic and its iconic characters.

Andrew Lloyd Webber, born in Kensington, London in 1948, is undeniably one of the most influential figures in musical theater. Raised in a profoundly musical household, his father was a renowned organist and director at the London College of Music, and his mother a dedicated piano teacher. While classical music dominated his upbringing, young Andrew introduced rock, pop, and theater to his family’s musical repertoire. By his early childhood, he was profoundly drawn to musical theater, thanks to familial connections in the arts and his innate passion.

Webber’s journey to stardom began in earnest during the late 1960s when he teamed up with lyricist Tim Rice. Their iconic creation, Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, was just the start of a groundbreaking collaboration. As his career progressed, Webber’s ability to interweave varied musical styles and narratives became evident, especially with globally acclaimed productions like Evita, Cats, and the unparalleled The Phantom of the Opera. These masterpieces showcased his talent for crafting narratives that deeply resonate with audiences, cementing his status in the annals of theater history.

Beyond his theatrical triumphs, Lloyd Webber’s accolades are vast: a knighthood, a peerage, numerous awards including Tonys, Grammys, and an Academy Award, to name a few. His work transcends generational and cultural divides, highlighting the universal appeal and transformative power of music and storytelling. Andrew Lloyd Webber’s legacy is not merely that of a composer; he is a beacon in the world of arts, exemplifying the limitless potential of human creativity.

What a joy to be with one of the legends in the whole world when it comes to music. How did it all start?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: I come from a musical family. My father was the director of Music of the London College of Music, and he was the senior, I suppose you might call, lecturer in composition, music composition, of the Royal College of Music. And my mother was a piano teacher who really specialized in teaching very young children. So, music was around me all the time. My brother, of course, was a leading concert cellist, and possibly was one time Britain’s most pianist. And so, the family was all music. But I was the one who didn’t really go for what’s called classical music, although I mean it was all around me all the time. I was the one who brought rock and pop, and of course, theater into my family. I had an aunt who was an actress, and possibly the theatrical side came from her. I was taken to musicals and opera when I was very, very small, and really, by the time I was seven or eight, even really as young as that, theater had grabbed me, and musical theater had grabbed me.

Do you remember the first time a song or a melody grabbed you?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: I can’t remember when, exactly, I composed my first, but my father organized it as some of my tunes, if you like—my sort of very, very juvenile tunes—were published when I was about eight, I guess. And it came out in a magazine called Music Teacher. I found a few of them the other day, and I was rather hoping that I’d find something which was absolutely wonderful that I can reuse. But, no. There was one little tiny bit of it that I seem to recognize in Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Coat. So, I suppose I wrote that pretty soon after if you think about it. I mean, I was 18 when I wrote, 19 when I wrote Joseph. I did enjoy writing for the theater pretty immediately. And then I built my own toy theater, and we did dreadful musicals, and they were on various subjects that I and my brother—we sort of got various long-suffering friends and parents around to listen to.

What’s a toy theater?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: It was a big toy theater. It had everything. It had a revolving stage made out of a grand fern. It was a great big thing.

In your house?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: In my house. Yes.

And how old were you?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: Well, I guess I was about ten by the time I did that.

Andrew Lloyd Webber: But theater absolutely grabbed me from a very, very early age. And I have also a great love of art and architecture. I mean, my other real interest was history, and particularly those days, medieval history grabbed me a lot. And so the other side of me, I was going around seeing ruined buildings and castles and abbeys and churches and there were cathedrals and things, so there was a time, there was a time when I even thought that that’s what I really wanted to go and do.

To be an architect?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: Well, no, not an architect. No, but to be actually involved with the conservation and preservation of buildings. And, I suppose that side of me has come out right now in the fact that I’m at the moment restoring and completely reconstructing the theater on Drury Lane, which is London’s oldest and really in many ways finest theater, which is one of mine. And so maybe my architectural side is coming to the surface right now.

And you have a castle in Ireland as well, right?

Well, actually, the castle in Ireland is lovely and wonderful and it is indeed a medieval castle with a house built into it. But the prime reason for that has nothing to do with my love of history. Although I must say it is a wonderful place to go to. I don’t hardly get there enough. But it’s a working stud and it’s the half of my wife’s horse breeding business, because she was a professional rider, a horse rider. And she started when we married, 30 years ago now. She started a stud to breed race horses. And it’s one … she’s actually built it into one the most successful small, you might say boutique studs in the world. And she bred last year the champion two-year-old. Now I’m out of my depth now. I really am. But that’s the stud in Ireland is where the castle is. And it’s kind of a vital half of what she does, because it’s wonderful land for horses I am told.

Well, let me go back to growing up in music. When you said music was around your house, were there instruments everywhere?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: Yes, music everywhere.

Andrew Lloyd Webber: My father had an electronic organ because he was a great organist, as well as everything else. He was the Musical Director for the Central Hall Westminster when I was very young, and he played the organ there. He was a famous organist in his day, and a very young man when he started to play the organ. He came from a very working-class background, and in those days, really playing the organ in churches was the way you kind of got started in his day. That was before the Second World War, so music was all around everywhere.

But it was your mother, you said she was an ace, an ace teacher. What do you mean?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: She was a very successful—not so much successful, is probably the wrong word, but she taught an awful lot of children. I still keep finding people who come up to me and say, you know, I was taught by your mother. And it’s extraordinary. But she also became very, very much involved with the career of a very young pianist in those days called John Lill, who went on to win the Tchaikovsky competition. And he sort of moved in as a kind of older brother to Julian and me into the family. So there was him playing the piano as my father played the organ, there was me with my musical theater and my rock and pop, and my brother on the cello. And goodness knows what the neighbors thought.

But she let it … I mean, she obviously loved this. I just wonder, like parents are listening, what is it that parents are supposed to do for their kids?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: In my case, my parents rather gave up on me. They knew I was sort of really doing my own way and finding my own path. And I think, and possibly wisely, my father was not really very keen for me to be too formally musically educated. There was a time… I got what’s called a… it’s difficult to explain, but it’s called a demi-ship to Magdalen College, Oxford, in History. And I met Tim Rice by that point, so I decided really not to take it up, which the family had thought obviously was a pretty odd and weird thing to do. I suppose you could call it a scholarship or an exhibition to Oxford. They thought that was not a bit weird. But my dad didn’t. And he knew that I would really do what I wanted to do. And I met Tim Rice by that point. He was five years older than me, and when you’re 17, which I was then, and Tim was 21, that’s a big age gap. And I was very worried that I might lose Tim Rice, and he might go off and do other things because he had other… he was working at EMI records at that point, and he could have well gone off and really had a career away from me.

You were only 17, you were aware that you were pretty darn good with melodies. And how is it that you knew that Tim Rice would have been a good collaborator?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: I did do a term at Oxford, and I got myself very into Oxford theater very, very fast. And I thought I’d find, you know, other people who could really write lyrics and, you know what, I realized very, very quickly that lyric writing, good lyric writing is very, very, very specific, and good lyricists do not grow on trees. And I realized that Tim and his turn of phrase and everything he was doing was very special. So I think the proof in the pudding really was the first thing we wrote, which was Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Coat. Wasn’t actually the first thing we wrote, because we did a musical that never got on, which was this sort of commission. But you listen to Joseph, and we just had a revival of it in the London Palladium, which has been an enormous success in London. And I was struck. I had nothing to do with this revival. I just went to it as if I was an ordinary member of the public really. And I was so struck by how his words and everything is still fresh over 50 years later after we wrote it. And I think that answers your question. I knew very, very early on that his words were special. And his London was very much what they called swinging London in those days, and what I caught the tail end of it. But again I was an odd animal, because everybody else was doing rock and pop. And all that rock and pop was a huge part of my background. I still wanted to do musicals. And musicals were not what people were doing then, particularly in Britain.

And here you are a teenager, you’re sitting at the piano, you played the melody for Tim Rice. How does it work? Can you tell us how the creative process works?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: Anything to do with musical theater, which is really what I do, I mean, you can write melodies in isolation. Yes, of course, one can think of them any time; they can come in the middle… I can think of one in the middle of this interview. But really, with musicals, everything starts and finishes with a story. I am a firm believer that a great musical score can’t carry a bad story. Whereas a really great story can carry an okay musical score. A really great example of a great story carrying, well, not carrying, but serviced by a fantastic score, would be Romeo and Juliet, West Side Story. Or if you want to go Shakespeare, Hamlet, the Lion King, because the Lion King is really the story of Hamlet. And those are all great stories. And in my case, I found that I’d done certain musicals where perhaps the story isn’t really strong enough, and no matter what I had written, I think that the musical would never really have been as successful as it would have been if it had been a great story.

Andrew Lloyd Webber: The story of Joseph is wonderful because it’s a very simple, primal tale about jealousy and then redemption and forgiveness. And that’s a primal tale. I mean, the story … I mean, thinking of the Tim Rice ones, it’s a story of, well, the last seven days of Jesus Christ is pretty good. And Evita, you know, which was very much Tim Rice’s idea, a very interesting idea, I think looking back at it to have written in 1975, ’76, which is when we wrote it, because it was in a way probably much more about what was going on at the time in our own country, Britain.

The way that the trades unions had actually caused the overthrow of an elected government. Although we didn’t perhaps think about it at the time that way, I suppose that’s why the story of Eva Peron and the way that you get an extremist like her and an attractive extremist as well, and a young one, coupled with Juan Peron as President, you could see…

Do you think it was easier to write, in that case it was a political story.

Andrew Lloyd Webber: I thought of it as more of a political story probably than Tim Rice did.

Was it easier to write maybe about Argentina than home, what was going on in England?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: In one sense, you writing about home is quite difficult because it is something that is actually going on. But what I’m saying is that I think it influenced what we were doing. Of course, the one show that you would come around and say, ‘Well, he’s talking nonsense about great story,’ would be Cats because Cats hasn’t really got a story. That was me trying to do something that I hadn’t done before. I mean, my mother used to read me the T.S. Eliot cat poems in Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats when I was a little boy. And Tim Rice always liked to really write to melodies, in case we found the dramatic situation. And I wrote for the dramatic situation or where I thought that I could take the music in tandem with the story. But with Cats, what I wanted to do was to see if I could set existing verse, because I’d never done that before. So I started setting the poems, thinking of them as a concert piece. And because of Valerie Eliot, who was T.S. Eliot’s widow, gave me some other poems, which were not actually published as Old Possum. I thought I’d got something bigger. I wasn’t sure what it was. And that evolved. It’s a long, long story, but that evolved into Cats, the musical, which was very, very much about dance, which was happening in Britain at the time and a whole load of areas of theater that I hadn’t really got into. But primarily it started because I wanted to see if I could set existing poetry to music.

A lot of people have read T.S. Eliot. Only Andrew Lloyd Webber thought about making that a musical. What is it that’s a little bit different about how your creative mind works?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: I didn’t think initially of Cats as a musical. I thought that if I could set these poems, maybe they’d have a life as a kind of concert piece, a little bit like there were words in Peter and the Wolf, you know, but I was thinking if I could actually set these things, maybe there’d be a life, you know, a 40-minute concert in which… or they could be sung as part of a program where there was other music, and never, ever thought of it as a musical. Until Valerie Eliot gave the story of Grizabella, the Glamour Cat, which wasn’t in the book. And that’s when I thought maybe there’s something bigger in all of this. Initially again, I thought of it maybe as a companion piece to in the theater, like a 45-minute, maybe an hour companion piece to something which I had written before, which was a series of Paganini variations that I wrote for my brother, which became a very, in Britain, was a very successful album. And there were a lot of people saying, ‘Can we choreograph this?’ And I’d wonder whether you could put Cats together with the variations as a two-part evening. And I actually explored that for quite a long time. So, kind of Cats evolved almost by accident.

Maybe the better word is it evolved. But it was very much, even when it got to the point that we were going to try it as a musical and we had a cast together, unlike any of my other shows, a lot of it was created in the rehearsal room. I mean, a lot of it was me writing music, something I’ve never really specifically done before, for dance. And so quite a lot of the music was very much of its time, if that makes … as you probably would understand. I mean, the dance was exploding in Britain. I have Gillian Lynn as the choreographer. And it was very much with her.

So if you hear something on the radio that day or you think of something else you can change it in the moment? Were you really absorbing what was happening at the time?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: Well, it was just that there was … the word that we don’t have in British that doesn’t translate well in English that doesn’t really have an equivalent, but the German word zeitgeist. I mean, I think Cats is very, very much a part of what was going on in London at that time. And a lot of it was young kids going around with their leg warmers and going to Pineapple Dance Center and everything. Dance suddenly seemed to be cool in Britain. And I kind of wanted to write, you see I was only 29, 30 when all of this was going on. And I’d done Evita. And I had written my Paganini variations, which again was trying to see if I could do something instrumental and write a 35-minute piece with no words, to see if it could hold. And then I did something called Tell Me on a Sunday, which was a one-woman show. I just wanted to see whether I could do that. At that time I was very restless and wanting to see if I could do things that I hadn’t done and challenge myself. And I’d also worked with Hal Prince on Evita, which was a great thing.

You were only 13 when you sent a letter to Richard Rodgers. Did you think you had a gift?

Andrew Lloyd Webber: I didn’t know. I wouldn’t have known at that time.

Andrew Lloyd Webber: I certainly wrote to him and said he had a gift for melody. And I very much wanted to meet him. But, in fact, I didn’t meet him until I had written Jesus Christ Superstar, and it had become quite a big hit here on record at that time. Well, actually, it was getting very big in 1970. And he was apparently very keen to meet me too. So we did meet. He talked a lot actually about Jesus Christ Superstar, which I didn’t want to talk about at all. He was interested in whether or not I thought that writing what you might call through-written or through-composed musical, where there wasn’t any dialogue, which is really opera, whether you like it in another word, was going to be the new way through and whether the musicals with book scripts were something that was going to disappear. Because I suppose Jesus Christ Superstar was one of the first, it was more or less the first musical of its kind where there wasn’t any spoken dialogue. And I was very much, it pains to say to him that I always think everything is horses for courses. I mean, yes, I suppose probably my most famous shows are more or less completely through-written and through-composed because I like writing that way, because it means that as a composer I’m in control of the dramatic arc of the evening, and the music is driving it along with the story. But, look, I just did School of Rock, and School of Rock is something that absolutely has to have a script because the tempo of the whole thing is to be driven with dialogue as well as music. So there is no rule. But that’s what we talked about. But I didn’t get from him what I really wanted to get out of him, which was how his personality as a musician completely changed when he was writing with Hammerstein compared to his early years when he was writing with Lawrence Hart. I mean, you can see a little bit of the Rodgers you find in Hammerstein occasionally in the work that he did with Hart, but it’s like two different people. And that’s what I wanted to ask him, and he kept on asking me about Jesus Christ Superstar.