Educated people can be influenced by propaganda, but common people look at life simply and they tell the truth — the story as it is.

Svetlana Alexandrovna Alexievich was born in the town of Stanislav — since renamed Ivano-Frankivsk — in western Ukraine. Her mother was Ukrainian, her father Belarusian, and Svetlana grew up in a small village in her father’s homeland of Belarus. At the time, Ukraine and Belarus were two of the 15 constituent republics of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Under Soviet rule, Russian was the dominant language. Svetlana’s parents were schoolteachers, and she grew up steeped in the traditions of Russian literature.

From an early age, she was fascinated by tales that the women of her village told of the terrible times they had lived through. They spoke of revolution, civil war, famine, terror, and above all, the Second World War. From 1941 to 1945, the Soviet Union repelled invasion by Hitler’s Germany in the largest and most destructive struggle in the history of warfare. More than 20 million Soviet citizens were killed in the war — the actual figure may be as high as 27 million. Belarus alone lost a third of its population, and no one who survived was untouched by the suffering of the war years. These stories have haunted Alexievich all her life and inspired much of her later work.

Svetlana Alexievich began working as a reporter for local newspapers shortly after graduating from secondary school. As a student at the Belarus State University in Minsk, she studied with the Belarusian writer Ales Adamovich, a former partisan fighter who compiled stirring oral histories of the war. To this day, Alexievich credits Adamovich as the writer who has had the single greatest influence on her own work.

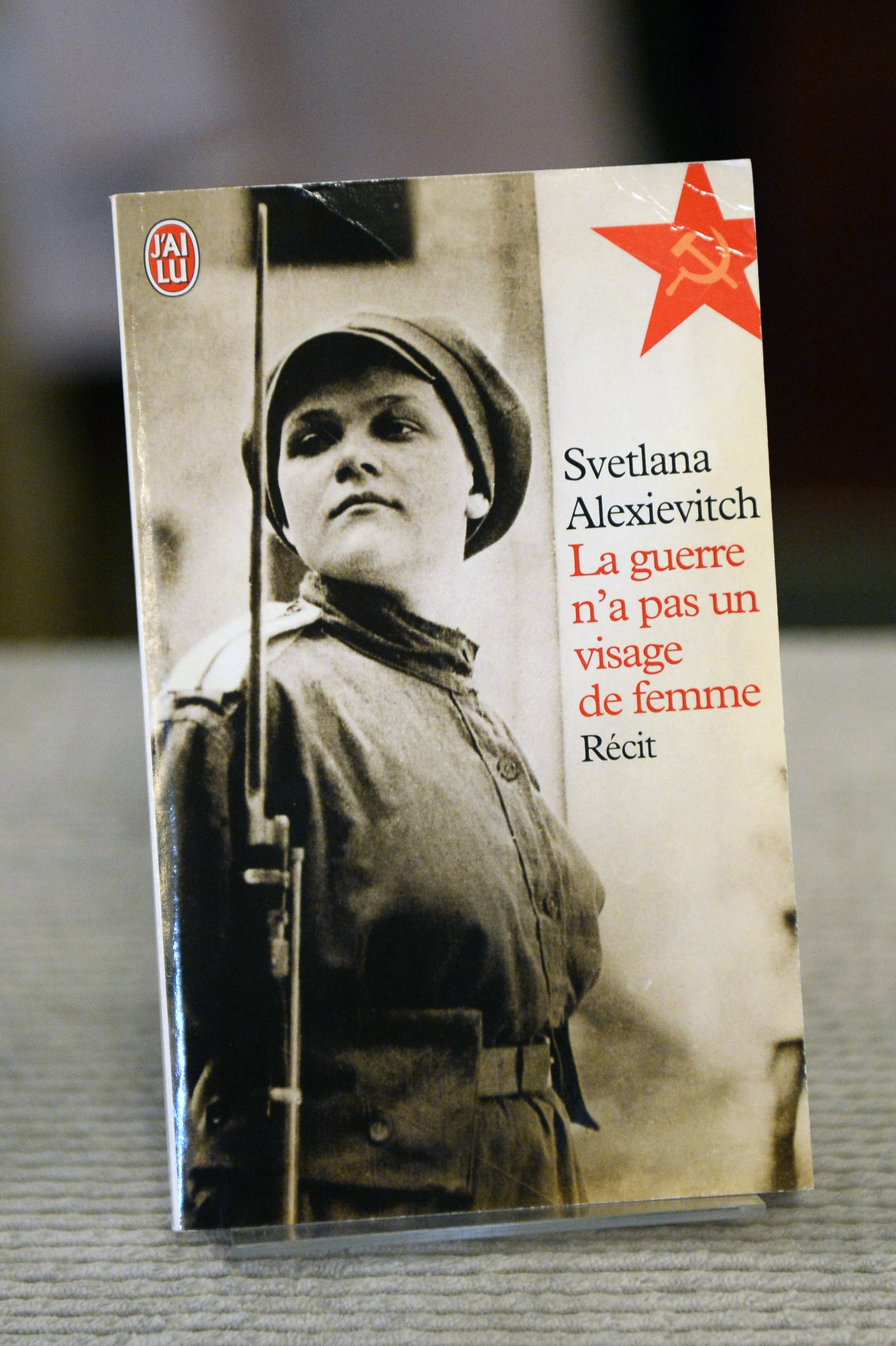

Although Alexievich enjoyed some success as a journalist and interviewer, when she began to craft a book from women’s memories of the war, Soviet publishers rejected them for not conforming to the official heroic narrative of Soviet victory in the “Great Patriotic War.” Unlike the women of the other combatant nations, Soviet women served in combat, fighting and dying alongside their male comrades in the desperate defense of their ravaged homeland. In selecting and preserving their memories, Alexievich emphasized the details ignored in other accounts of the war — the countless small ways in which women warriors fought not only to save their country but to preserve their own humanity in the most dehumanizing circumstances.

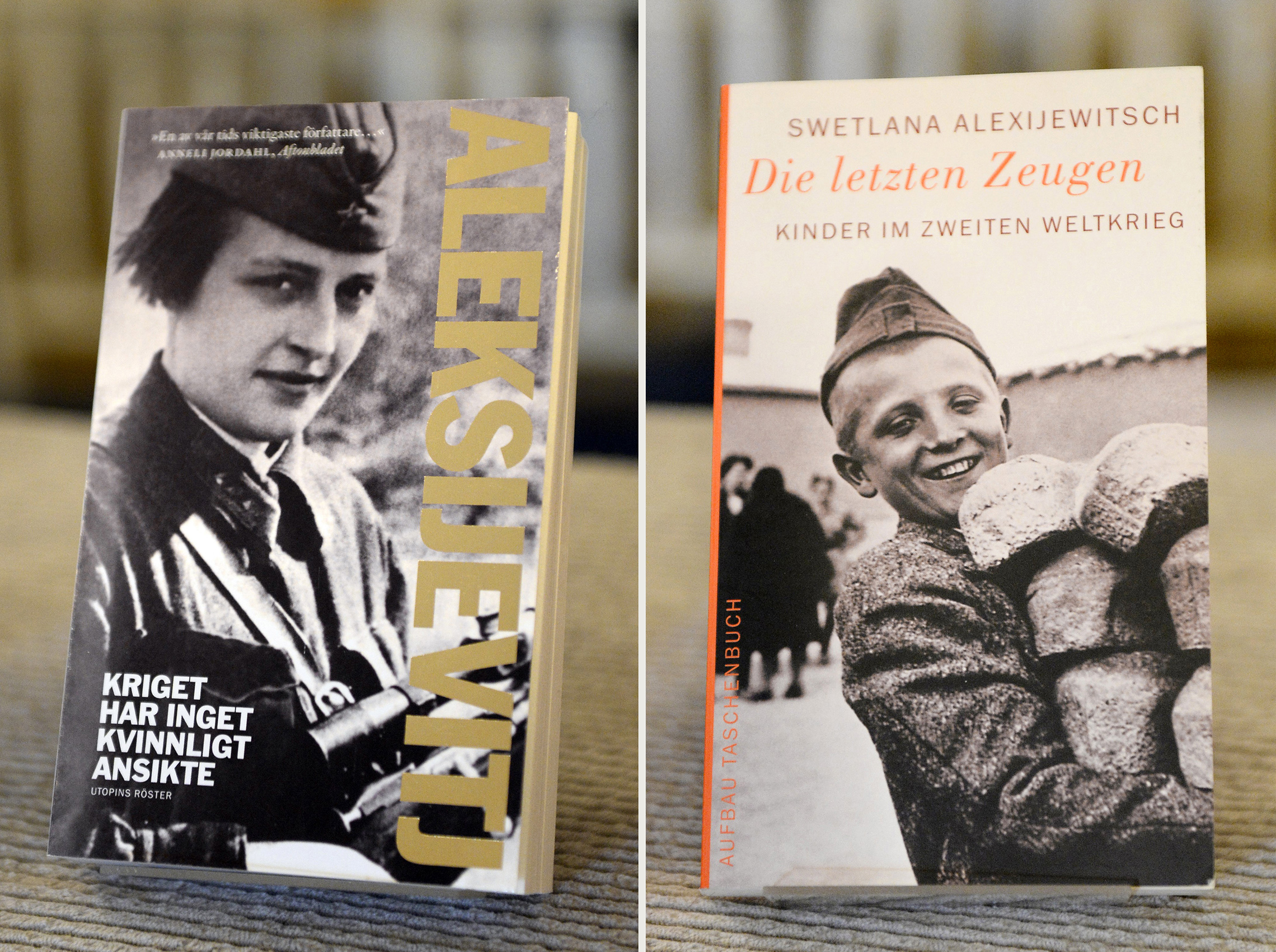

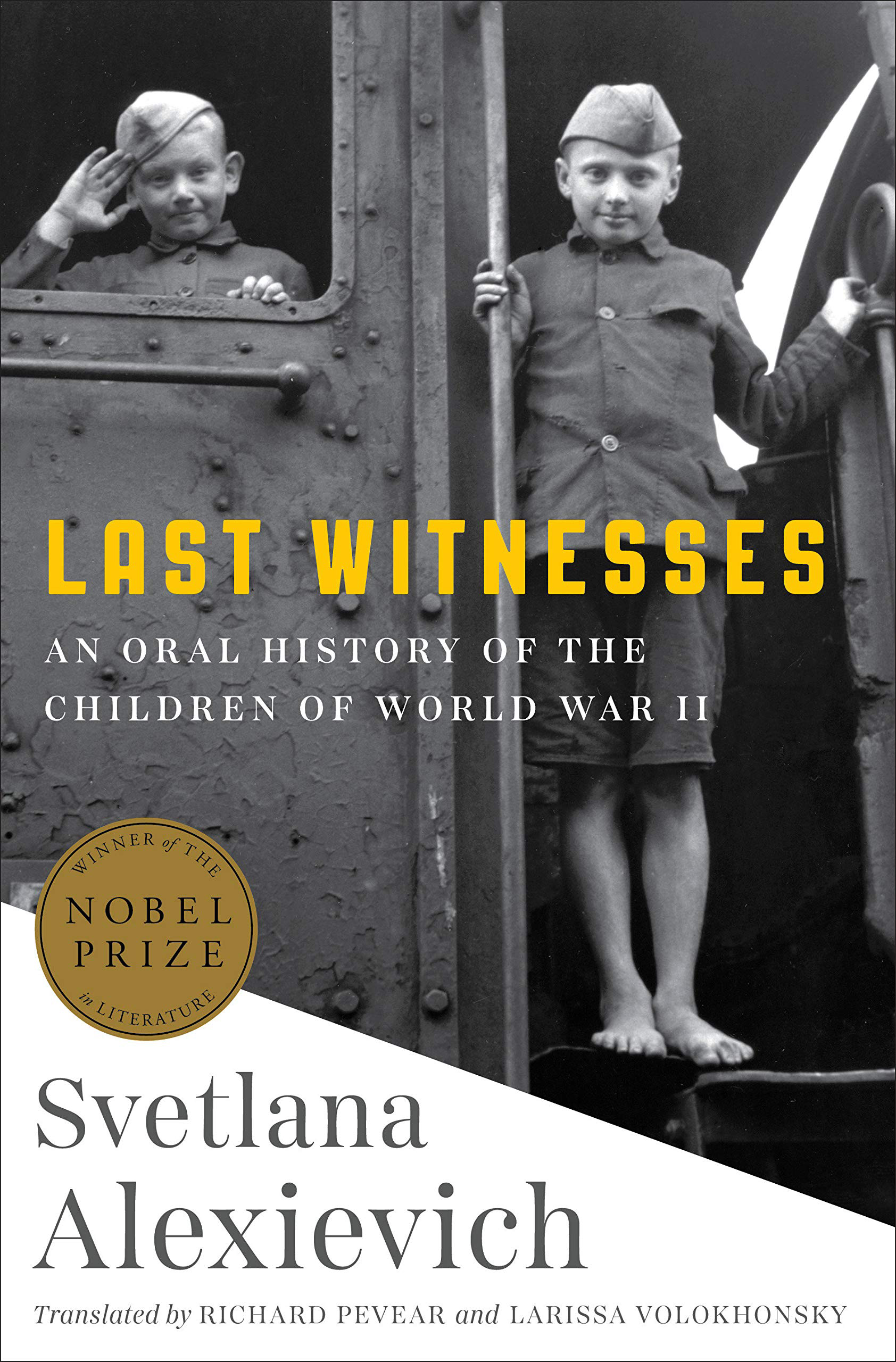

In the mid-1980s, a new Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, promoted a policy of glasnost or openness. An abridged version of Alexievich’s book The Unwomanly Face of War appeared in a Soviet literary journal in 1984, and the following year, with Gorbachev’s implied blessing, the entire work was published in book form. The Unwomanly Face of War was an immediate success in the Soviet Union and abroad and soon sold over two million copies. Alexievich followed it with The Last Witnesses, compiled from the accounts of those who survived the war as children.

In these and her subsequent books, Alexievich has edited lengthy interviews into tiny fragments, placing them one by one into a complex but coherent narrative. Allowing her subjects to speak for themselves, she has progressively minimized her own role as interpreter or commentator. The effect of her work has been compared variously to a mosaic or a choral symphony, in which many voices are heard, creating a detailed panoramic picture of a given era in history.

In the last years of the Soviet Union, Alexievich’s books found great favor with everyday readers and official recognition from the literary establishment. She received the USSR’s Order of the Badge of Honour and awards from the Union of Soviet Writers and the nation’s Literaturnaya Gazeta (Literary Newspaper).

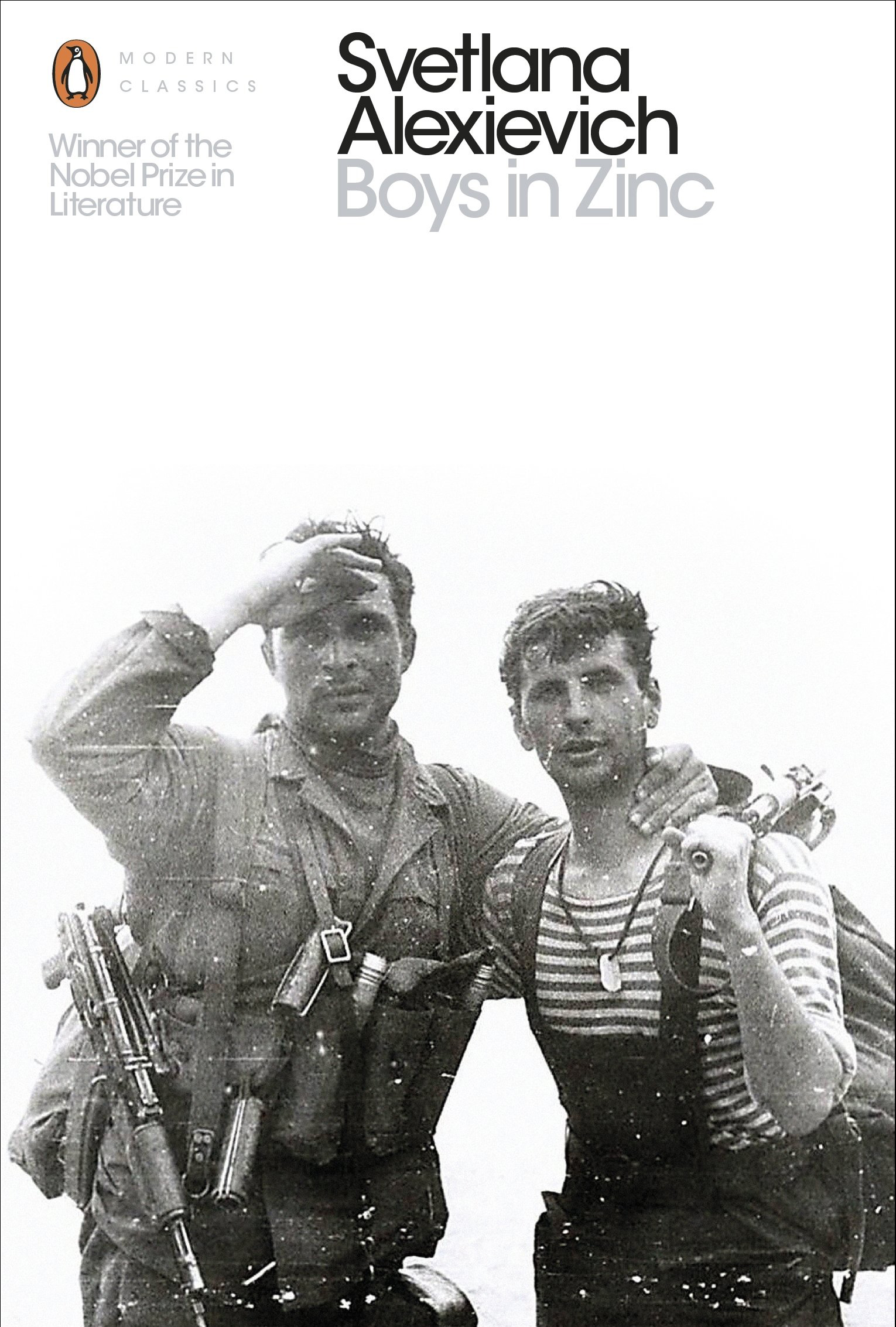

In 1991, as the Soviet Union was coming to an end, Alexievich published an oral history of one of the system’s last traumatic chapters, its long and inconclusive war in Afghanistan. Translated literally as Zinky Boys in the United States, and as Boys in Zinc in the United Kingdom, the title refers to the zinc coffins in which the remains of Soviet soldiers were returned home for burial. Many of the interview subjects described atrocities they had witnessed or participated in, shocking readers accustomed to the sanitized war stories Soviet authors had published for over half a century.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the communist system wrought enormous changes in the lives of Russians and of all the former citizens of the Union. For many, the loss of an old way of life and the system of beliefs that justified it was unbearable. Alexievich documented many such cases in her 1993 book, Enchanted with Death, a study of former Soviet citizens who had committed suicide in their despair.

One consequence of the end of Soviet power was the independence of Belarus. Alexander Lukashenko became the first president of the new republic. Initially seen as a patriotic reformer, Lukashenko soon moved to consolidate his personal power, muzzling his opponents, curbing the press, and suppressing civic institutions. In over 20 years in office, he has shown no signs of relinquishing power; neighboring countries have condemned his regime as “the last dictatorship in Europe.”

The relentlessly honest portrayal of Soviet and post-Soviet history in Alexievich’s work is at odds with the idealized version preferred by President Lukashenko and his supporters. In Russia, as well as Belarus, Alexievich’s critics denounced her work as a libel on the Soviet people. Since 1993, the state-controlled publishing houses of Belarus have refused to publish Alexievich’s books.

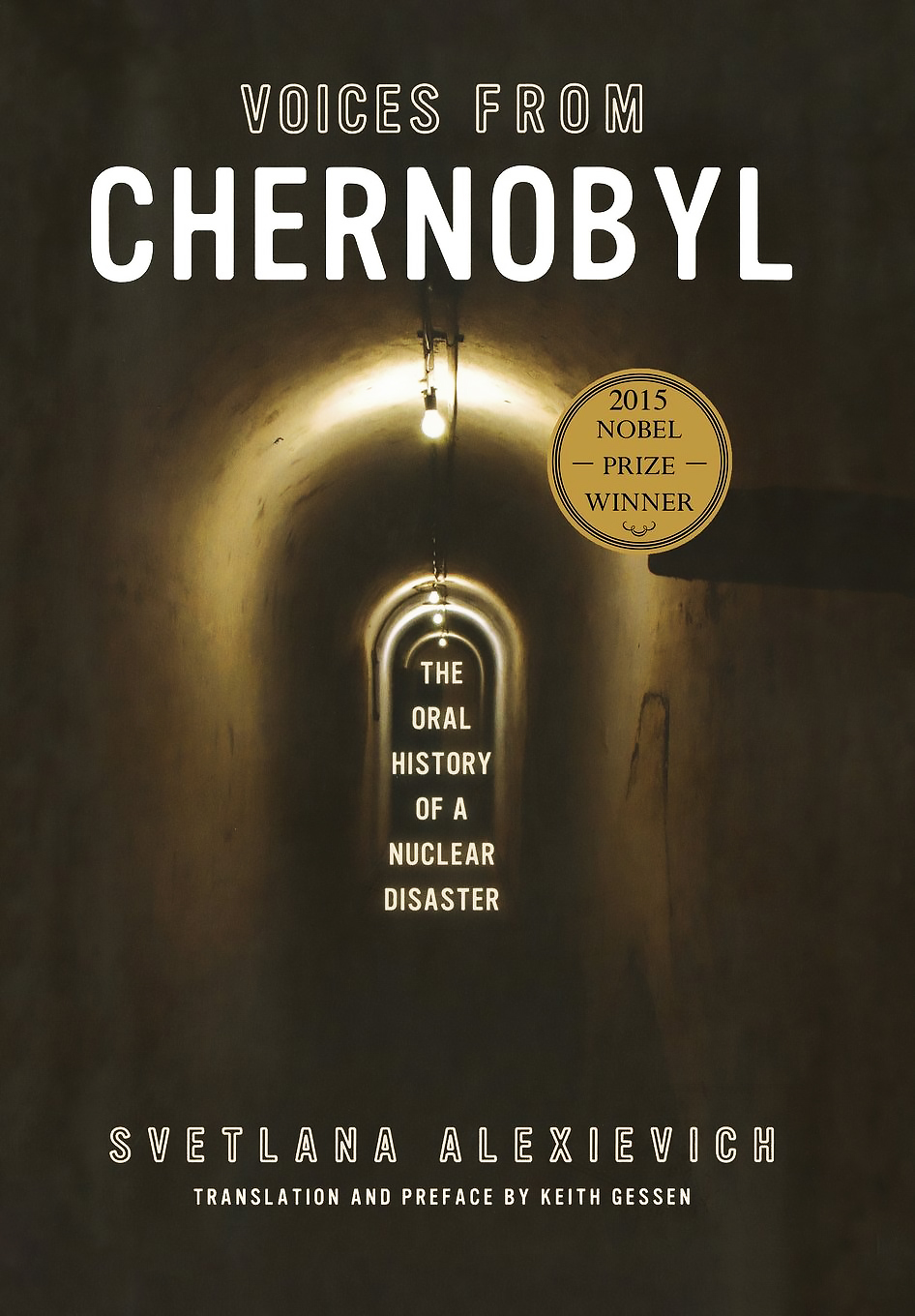

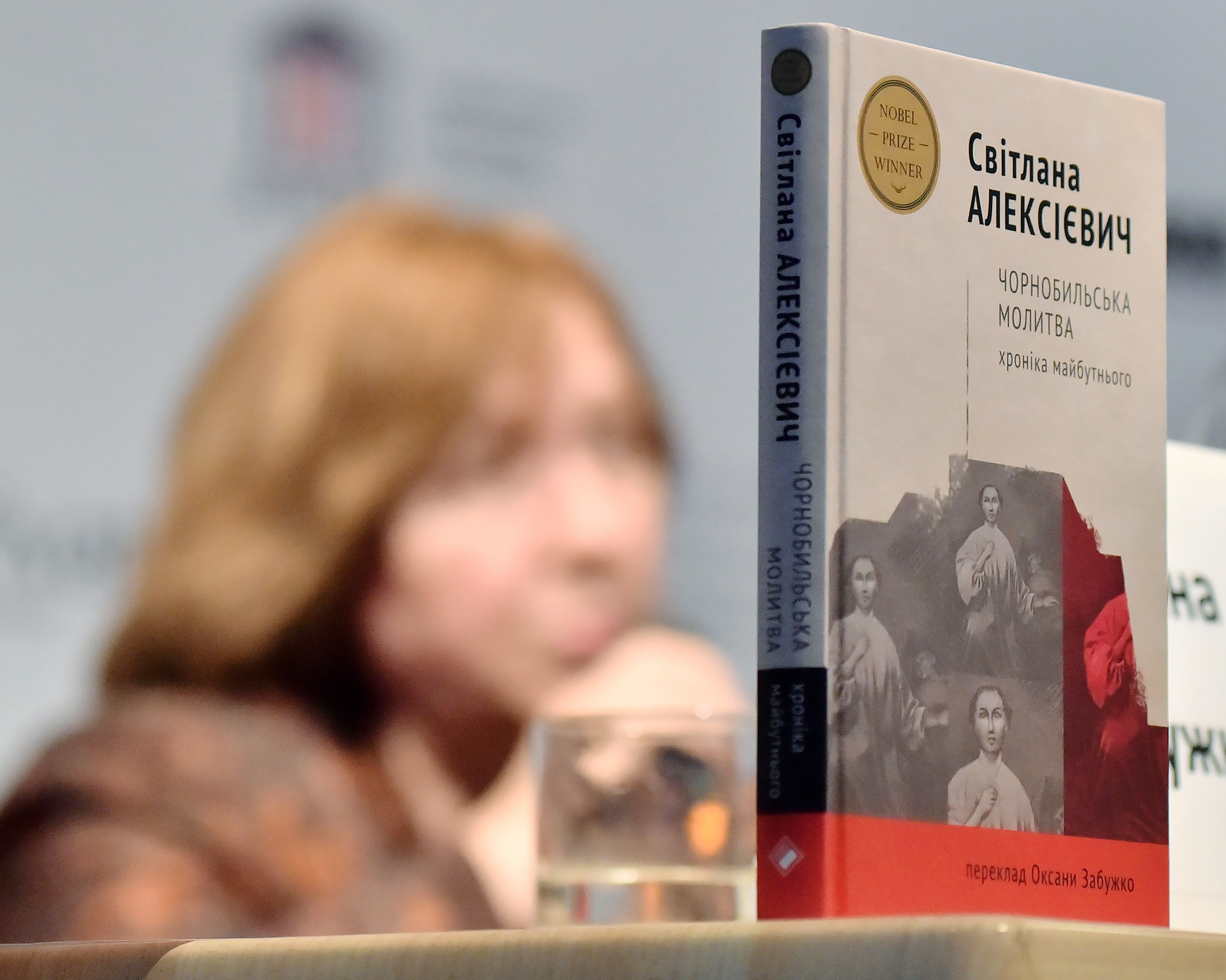

The 1986 failure of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine created an environmental disaster in both Ukraine and Belarus. The health effects of radiation exposure in the region are an object of controversy in the affected countries, but cancer rates among adults and children have spiked dramatically in Belarus, and thousands of deaths in both countries have been attributed to the aftereffects of the disaster. A decade later, memories of the disaster had faded in much of the world. In her 1997 book, Voices from Chernobyl (published in the UK as Chernobyl Prayer), Alexievich allowed the survivors of the disaster to speak for themselves before their voices were silenced forever.

A private publisher was willing to bring out Voices of Chernobyl in Belarus, but in the first decade of her country’s independence, Alexievich’s position became increasingly precarious. Alexievich registered her objection to the Lukashenko regime by leaving the country and going into voluntary exile. She expected to return in a short period of time, but as it happened, she spent much of the next ten years in Paris, Berlin, and in Gothenburg, Sweden. She spent her years abroad painstakingly editing the interviews she had collected with ordinary Russians and others since the fall of the Soviet Union. In 2011, after nearly ten years abroad, with work on her latest book nearing completion, she made the difficult decision to return to her home in Belarus. Years in the making, the resulting book would be hailed as her magnum opus when it was published in 2014.

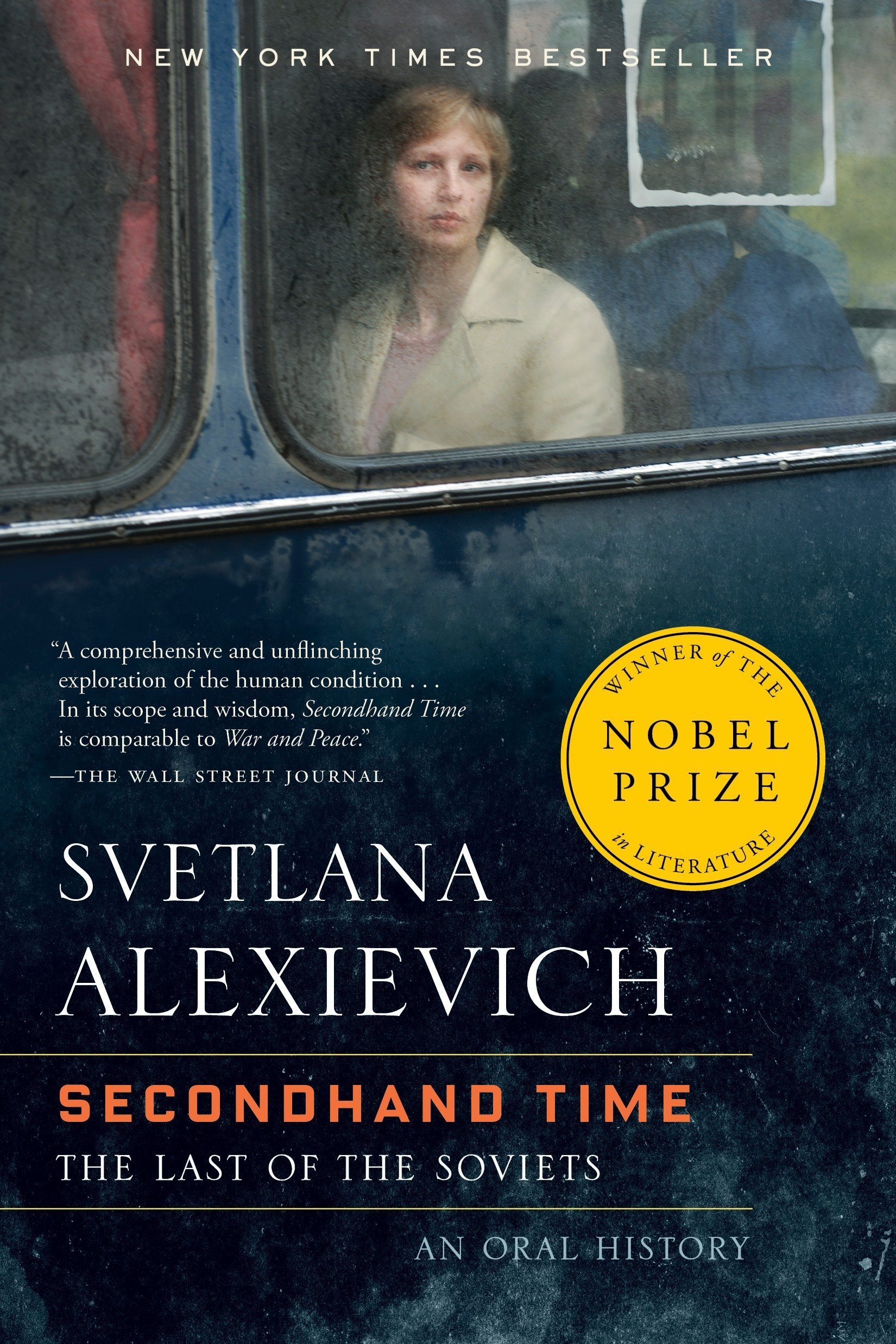

Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets is a sweeping account of the tortured life and slow death of the Soviet dream. Alexievich acknowledges the idealism of the founding generation of the Soviet state and the courage of the generations who struggled to build a better society from the wreckage of Imperial Russia while defending their country — at enormous cost — from invasion by Hitler’s Germany. In the end, she concludes, the revolution only succeeded in replacing one tyranny with another. Alexievich’s views of the post-Soviet era are not brighter. Centuries of despotism left the Russian people unprepared for self-government, she believes, and susceptible to nostalgia for the old dictatorship and the temptations of corrupt, authoritarian rule.

June 25, 2018: Belarusian writer, journalist, and Nobel Prize in Literature recipient Svetlana Alexievich holds her portrait during the presentation of a series of books called The Voices of Utopia, in Minsk. (Sergei Gapon/Getty)Secondhand Time created a sensation in the West, controversy in Russia, and was issued by a private publisher in Belarus, despite the official boycott of Alexievich’s work. The Swedish Academy awarded Alexievich the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature “for her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time.”

Today, Svetlana Alexievich continues to live in Minsk, although the government prohibits her from speaking in schools or appearing on television or radio. In 2019 she published Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II.

Svetlana Alexievich has created a new literary form to tell the story of modern Russia, not through the acts of parliaments and presidents, but with the voices of ordinary men and women, swept along by the currents of history. In her “novels of voices” she orchestrates hundreds of interviews into a symphonic panorama of history.

Her magnum opus, Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets, examines the collapse of the Soviet Union and its aftermath, when hundreds of millions of men and women saw everything they had believed in swept away virtually overnight. In their struggle to adapt to a new way of life, Alexievich hears a people trapped between the failed dream of a socialist utopia and the “spiritual wasteland” of a society based solely on the pursuit of material gain.

In awarding Alexievich the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature, the Swedish Academy praised her work as “a monument to suffering and courage in our time.” While her books focus with unflinching honesty on the people of her homeland, they speak in loud, clear voices to all of us.

Most of the authors who have received the Nobel Prize are novelists, poets, or playwrights. Your work is completely different. You interview real people and let them speak for themselves. How did you come to be so interested in these people and their stories?

Svetlana Alexievich: A lot changed during the last 20, 30 years — music, art. Why shouldn’t literature change as well? We cannot have the same literature as Tolstoy wrote. My parents were teachers in a village, and I spent my whole childhood in a village. And what I heard from simple women on the street, their stories were more amazing than any books I read. Their stories were horrifying, interesting, and very different. It made a big impression on me and had a great influence on what I wrote because some things were so much stronger and heavier than anything I read before. I feel very sad that many conversations between people on the street, between parents and children, they are disappearing. But I feel it’s also part of literature.

Were you the sort of child who stood listening in the kitchen while the grown-ups talked after dinner?

Svetlana Alexievich: I couldn’t say that I heard all the stories in the kitchen, but I heard a lot of stories on the street. I spent a lot of time on the street and outside. And usually, after work, women would come and spend some time together, sitting on the bench, telling stories. Some stories were about the war, and some stories were about love, and it was very interesting to me.

Do you remember any particular story that stuck with you that you could give us as an example?

Svetlana Alexievich: In Russia, there is a day of memory of the dead, where everybody gathers together at the cemetery to remember those who died before. I remember seeing this particular woman always sitting alone at the cemetery, and I was wondering why. Why is she always alone? I found out that during the war, when people were hiding from the Germans, she had a baby who was always crying because the baby was hungry. And people were scared that they will be found out because that baby was crying so much. So they told her to drown the baby and she did. But because the baby died, they actually judged her for that, and they isolated her and didn’t want anything to do with her.

There’s another story I’d like to tell you that’s from the time when I was in Belarus. Usually, in the summer, we would go visit my grandma in Ukraine. I would go to the fields to help her there, and she would usually tell me, “Please don’t go through the forest,” and I was wondering why. Well, during the war, a lot of people died there — Russians and Germans. After the war, the bodies of the Russian people were collected and buried elsewhere, but the bodies of German people were left there, and they were not touched. And even now, you can see in that field, and in that part of the forest, the bodies there. You can find bones, and it’s horrifying.

I heard about horrors from childhood. You probably know about the big famine in the Ukraine, a famine that Stalin started because the Ukrainian nation didn’t obey him. And I remember there was a certain house on the field, and every time we passed that house, my grandma would tell me, “Shh. Quiet, quiet.” And I was wondering why she is telling us to be quiet.

Later, when I grew up, she told me the story. During the famine, people were eating everything. They were eating dung and waste from people and from animals. And this one woman who lived in the house, she ate her two children, and she was separated by the village — she lived alone. And I remember how scared I was to walk past that house. And this story of our nation, it has had a great influence on me, and I wanted to tell those stories.

Your books are composed of interviews, but your selection and arrangement of the words of others are an art form as well. Why did you adopt this method, rather than writing a conventional narrative or history?

Svetlana Alexievich: If I tried to describe the stories that I heard, in my own words — there are thousands of stories. One of the books, it took me 40 years. And if I tried to describe it in my own words, it wouldn’t be the same. If I described it in my own words, then there would be no power or diversity that was described in interviews. And life is art. That’s what makes it different.

It takes me a long time to write every book, about seven to ten years. For every book, I interview about 700 people, and I write thousands of pages, and sometimes an interview with one person can take a few days. So I need to create a picture. You can say it’s like music, a symphony — out of the chaos of different stories — and that is an art in itself. You can say that every story is like a brick, and you can say that they’re not really so unusual on their own. But when you put it all together, you build an amazing building.

Now is an interesting time when, actually, fiction disappoints people because fiction used to be used for propaganda, so people are looking for something new. And that’s why I think that the only hero — the only character that people will believe — is the actual witness. I’m not choosing some special people. I’m just choosing ordinary people because that’s important.

These people didn’t mean much to the system, and their life — their stories — would otherwise disappear. Nobody asked them any questions about their life. Those people were just used by the system, including socialism. But I wanted to record it. I asked those questions. In a way, it’s a double trust when you interview common people. Educated people can be influenced by the propaganda, but common people look at life simply, and they tell the truth — the story as it is. People are connected with time — through radio and TV — and it’s important to give them the freedom to look at things differently.

The way you combine your interviews, you break them up into very small pieces and arrange them throughout the book in a complex pattern. Sometimes you use your subject’s real names and sometimes you don’t. Is there a reason for that?

Svetlana Alexievich: I have a different style of documentary. Before, people thought that you cannot really include something intimate or something that is particular to that person. I include everything. I don’t edit what they say. Sometimes people did ask me if they could stay anonymous because they were afraid of the KGB or neighbors that could spy on them or tell on them. They wanted to feel secure and protected. And yes, they would ask me not to say their name.

In one of the stories about Chernobyl, one of the women told a story about her husband. He was dying from cancer. It’s a horrible story. Her husband was at the end of his life, and doctors had no hope for him. There was no pain relief, and he was sent home, and he would scream all day long. The only way his wife could handle it was to give him two liters of vodka a day, or she had to do even more terrible things. They really loved each other, but it was very difficult to live with him. He was a fireman, but he became a monster — the way he was behaving — and he looked very horrible. Even doctors didn’t like visiting him because of that.

One of the things that they were doing — he would clap his hands, and that was his sign, asking her to come to his bed to make love to him. And during that time, he would not scream. But she asked me not to tell that in the stories, because she didn’t want others to think that she is a perverted person. In the first edition, I actually changed her name. But when she read the book, she asked me why. And I told her, “Valentina, you asked me to change your name.” And she said, “No, I suffered. My husband suffered. I don’t want to disappear. I want people to know.”

There is a different story. It’s called Zinky Boys, about the war in Afghanistan. And one of the officers who was there was telling stories about tortures that they did to people there. For example, they were cutting people’s ears to take home as a souvenir, or how they raped women there. And I wrote everything, everything he told me. But later, when he was in Moscow, he gave me a call, and he said, “Why did you write that? Now I have problems with the KGB. Now my father, who is in the military, doesn’t want to know me.” So I discovered a new way to deal with it. I created a different chapter, with all the names who took part in the interviews, so that you couldn’t tell who told what story.

It’s life. It’s unpredictable, and I have to be flexible and see how it goes in every situation. I spoke to my colleague, Anna Politkovskaya, who wrote different stories about different people, real people. And she said, “Well, I spoke to this person, but later I found out he was killed. I spoke to that person, and he was killed as well.” We talked about how it’s important that we protect the people that we talk to— that it’s our responsibility.

In your Nobel lecture, you referred to your work as “the history of the soul.” In your book Secondhand Time, it’s the soul of Russians and the citizens of the other Soviet republics in the post-Soviet era. From the revolution to the present, it’s a story of hopes raised and then dashed over and over again for almost a century. After all your work, how do you see the Soviet era and its aftermath?

Svetlana Alexievich: I think that the idea of socialism is actually a good idea. But what the Bolsheviks did to the country, it’s a crime. When I was writing this book, I was actually studying a lot of memories of Bolsheviks; there are letters and other documents. And it’s interesting to see, in their youth, they were actually beautiful people, and they wanted to create a paradise. I think it’s an eternal Russian problem, the idealism. People were not ready for socialism yet, but they were forced into it. And Stalin actually was saying — one of his sayings was, in the camps where people were tortured — that “We need to force freedom on people.”

Of course, my generation was different, and I didn’t witness camps. My father told me about those days. He worked in the university, and he said many of the teachers from the universities were in camps. My generation didn’t see so much blood. People weren’t sent to their death. It’s a different time. I wrote, in parts of my book, about the notes of accomplices. I believe that we all were part of it because we believed in the same thing. We believed in the socialist idea; we believed in freedom; we believed in the better world. I remember, when I was young, we even were talking about going to other parts of Russia to develop it, to make it better. We were all idealists.

I would say my family was a common (typical) family. My father was director of a school. He was a member of the Communist Party. He went to war. That was his generation and his idea. And it’s difficult for that generation to say goodbye to all of those ideas. For example, when I was writing my book about Afghanistan, I told my father all of those stories, horror stories, about what was happening. I told him, “Those people, they are actually torturing people in Afghanistan.” When I told my father, he did not believe me, and he was crying.

When the period of glasnost — or openness — began, what did people believe that freedom would look like? And when communism ended, what did it actually look like?

I never was a member of the Communist Party, but still, it was difficult to build capitalism, to start from scratch, because it was something different, something new.

Svetlana Alexievich: In the ‘90s, we were all naïve. We just thought that we will finish the communism, and we will get freedom, and we will get a beautiful life. One thing we didn’t realize is that if somebody spent their whole life in prison, even if you let them out, it doesn’t mean that they will be free inside. There actually was no freedom; there was only talk of freedom. People who were in the Communist Party, they didn’t get their judgment; they were still in power. They not only had power but now they bought a lot of things. So they were very rich. So it is basically double power.

In those days, people were very confused because nobody from the top was explaining to them what was happening. I think Putin actually learned that lesson, and now there are a lot of explanations on TV and on radio, but in those days, people didn’t have a clue.

In many places, the Soviet generation is called sovok, but I think it’s very demeaning. I don’t like that word. I cannot call my father or his friends such a word because it was an amazing generation. They experienced a lot. They fought in the war, and that is not the word to describe them. That’s why I describe the history of the soul because it’s important to describe the world of feelings — what people experience inside.