The worst thing that can happen is death, and that's not the worst thing in the world either.

James Bond Stockdale was born and raised in Abingdon, Illinois. He lettered in football, basketball and track, won a regional piano competition, and graduated second in his high school class. He was appointed to the Naval Academy in the middle of World War II. Soon after graduating in 1946, Stockdale reported to Pensacola for flight training.

Stockdale flew almost every propeller-driven aircraft in the Navy’s inventory, but he yearned for greater challenges. In 1954, Stockdale applied for Test Pilot School at Patuxent River, Maryland. Along with 17 others — including future astronaut John Glenn — he made the cut.

At Patuxent, Stockdale was a standout. He amassed more than a thousand hours in the F-8U Crusader, then the Navy’s hottest fighter. Promotions followed, and by the mid-1960s, Stockdale was at the very pinnacle of his career and profession, commanding a fighter squadron.

In August 1964, Stockdale’s squadron played a role in the Gulf of Tonkin incident, which involved North Vietnamese attacks on U.S. naval vessels. The Johnson Administration invoked these occurrences to justify a massive American military response. Interestingly, Stockdale always maintained that during the incident’s key “engagement,” he saw no enemy vessels. In his words, “I flew so low there was salt spray on the windshield, and I still didn’t see a thing!” But the die was cast. The next morning, he was ordered to lead a raid on North Vietnamese oil refineries. America — and Jim Stockdale — were at war.

On September 9, 1965, Stockdale catapulted his A-4 Skyhawk off the flight deck of the USS Oriskany on what turned out to be his final mission over North Vietnam. Approaching his target, his plane was riddled with anti-aircraft fire. Within seconds, his engine was aflame and all hydraulic control was gone. He “punched out,” watching his plane slam into a rice paddy and explode in a fireball. Stockdale himself best describes what happened next:

“As I ejected from the plane, I broke a bone in my back, but that was only the beginning. I landed in the streets of a small village. A thundering herd was coming down on me. They were going to defend the honor of their town. It was the quarterback sack of the century.” They tore off his clothes and beat him mercilessly. Stockdale suffered a broken leg and paralyzed arm before a military policeman took him into custody. He was now a prisoner of war, the highest ranking naval officer to be held as a POW in Vietnam.

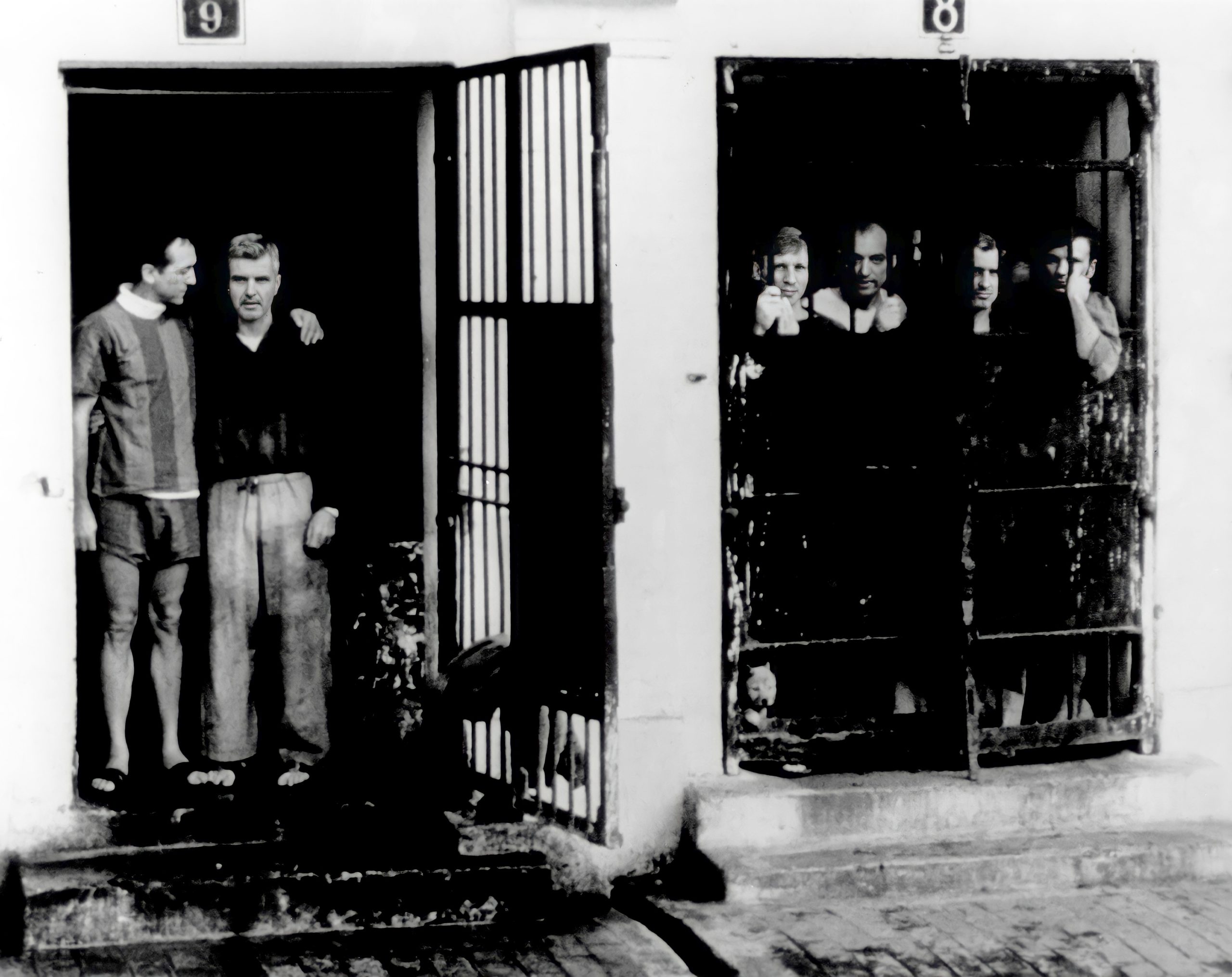

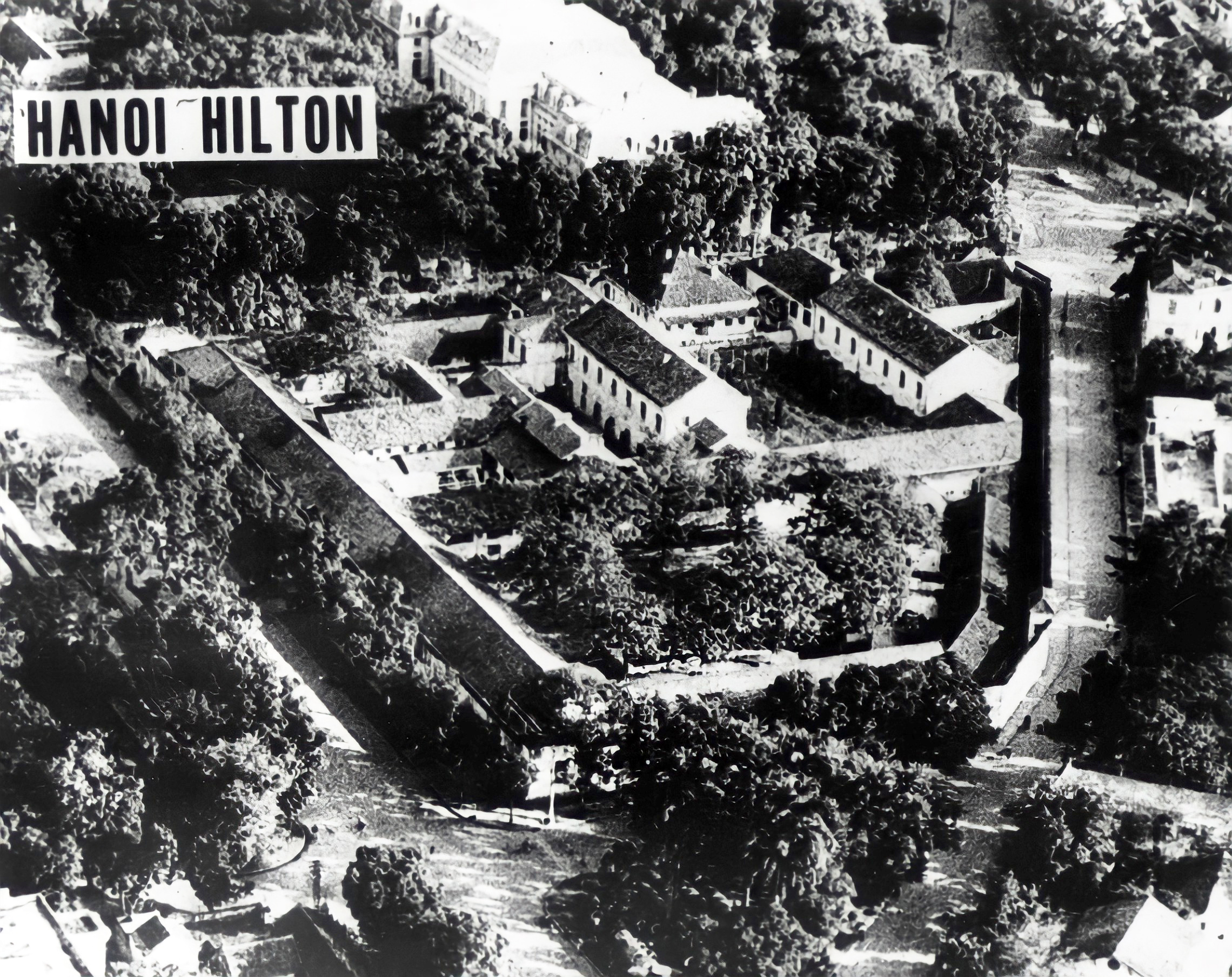

Stockdale wound up in Hoa Lo Prison – the infamous “Hanoi Hilton” — where he spent the next seven years under unimaginably brutal conditions. He was physically tortured no fewer than 15 times. Techniques included beatings, whippings, and near-asphyxiation with ropes. Mental torture was incessant. He was kept in solitary confinement, in total darkness, for four years, chained in heavy, abrasive leg irons for two years, malnourished due to a starvation diet, denied medical care, and deprived of letters from home in violation of the Geneva Convention.

Through it all, Stockdale’s captors held out the promise of better treatment if he would only admit that the United States was engaging in criminal behavior against the Vietnamese people, but Stockdale refused. Drawing strength from principles of stoic philosophy, Stockdale heroically resisted. His courage was an inspiration to his fellow POWs, with whom he communicated in an ingenious code, maintaining unit cohesion and morale. His jailers increased the level of torture, so Stockdale determined to fight back in the only way he could.

Told that he was to be taken “downtown” and paraded in front of foreign journalists, Stockdale slashed his scalp with a razor and beat himself in the face with a wooden stool. He reasoned that his captors would not dare display a prisoner who appeared to have been beaten. When he learned that his fellow prisoners were dying under torture, he slashed his wrists to show their captors that he preferred death to submission. Stockdale literally gambled with his life, and won.

Convinced of Stockdale’s determination to die rather than cooperate, the Communists ceased trying to extract bogus “confessions” from him. The torture of American prisoners ended, and treatment of all American POWs improved. Upon his release in 1973, Stockdale’s extraordinary heroism became widely known, and he received the Medal of Honor in the nation’s bicentennial year. He was one of the most highly decorated officers in the history of the Navy, with 26 personal combat decorations, including four Silver Star medals in addition to the Medal of Honor.

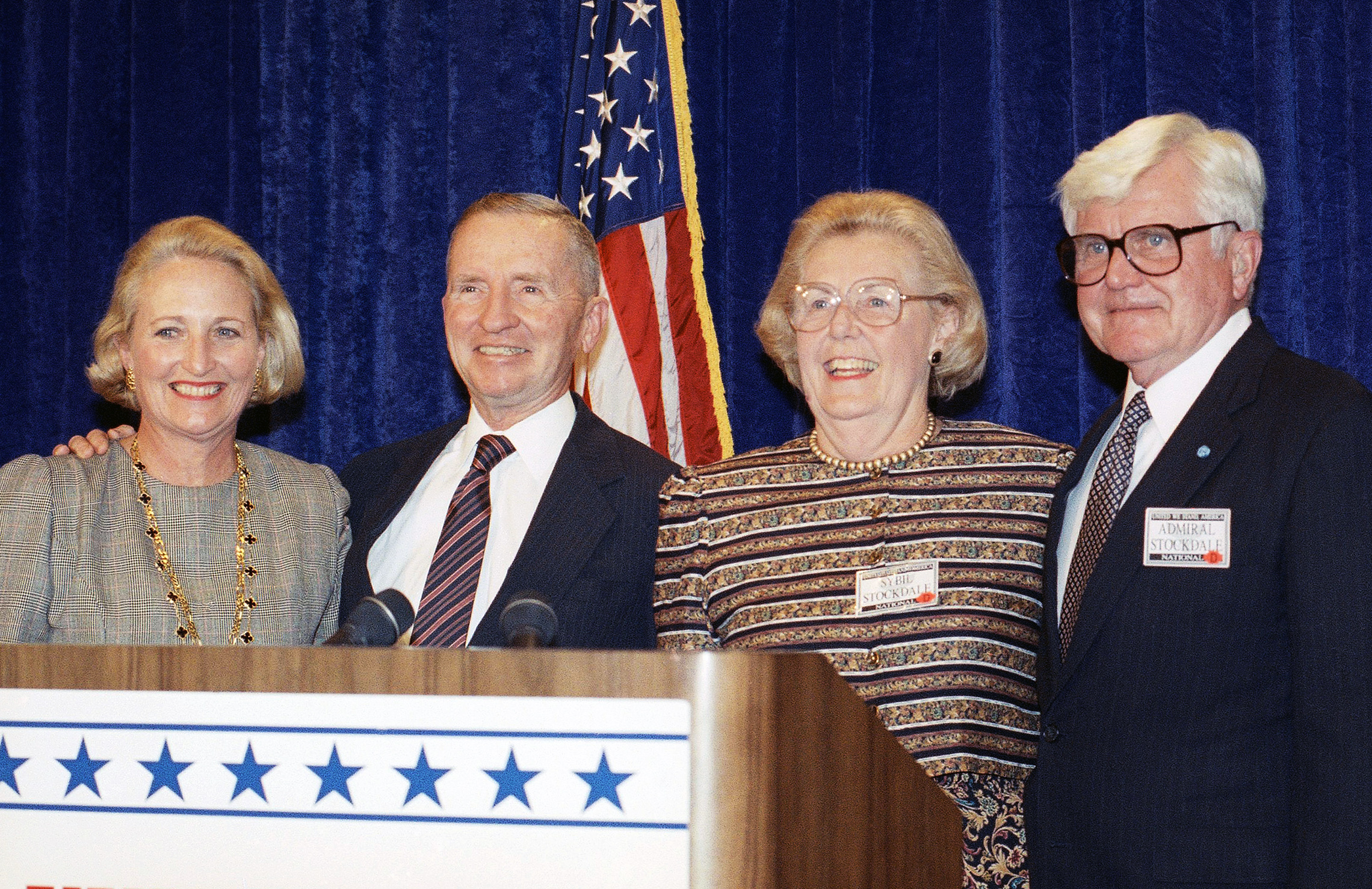

Throughout Stockdale’s captivity, his wife Sybil campaigned for respectful treatment for the families of all POWs by founding the League of Families. Sybil Stockdale was presented with the U.S. Navy Department’s Distinguished Public Service Award by the Chief of Naval Operations. She is the only wife of an active-duty officer ever to be so honored.

After serving as the president of the Naval War College, Stockdale retired from the Navy in 1978 and embarked on a distinguished academic career, including a term as president of the Citadel, and 15 years as a senior research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. In 1992 he graciously agreed to a request from his old friend H. Ross Perot to stand with Perot as the vice-presidential candidate of the Reform Party. Stockdale disliked the glare of publicity and partisan politics, but throughout the campaign he comported himself with the same integrity and dignity that marked his entire career. Together, the Stockdales told their story in a joint memoir, In Love and War. Admiral Stockdale and his wife lived quietly on Coronado Island, off of San Diego, until his death at age 81. In 2009, the U.S. Navy honored him by naming a new missile destroyer in his honor, the USS Stockdale.

“Stockdale…deliberately inflicted a near-mortal wound to his person in order to convince his captors of his willingness to give up his life rather than capitulate. He was subsequently discovered and revived by the North Vietnamese who, convinced of his indomitable spirit, abated in their employment of excessive harassment and torture toward all of the prisoners of war.”

So reads the Medal of Honor citation for James Bond Stockdale. Shot down over North Vietnam in 1965, he endured seven years of captivity as a prisoner of war, one of the longest such ordeals in American history. Tortured 15 times, he was forced to wear vise-like heavy leg irons for two years, and spent four of the seven years in solitary confinement, in total darkness.

Though his captors held his body prisoner, their relentless attempts to break his spirit never succeeded. Throughout his captivity, Stockdale’s steadfast refusal to cooperate with the enemy kept alive the spirit of resistance in his fellow POWs. When his story was told on his release in 1973, the story of his courage and endurance became an inspiration to Americans everywhere.

Whatever challenges we may face in the years to come, Americans and all freedom-loving peoples can fortify themselves with the example of Admiral James Bond Stockdale, an American hero for our time, and for all times.

We’re speaking with Admiral James Stockdale, who was awarded the Medal of Honor after enduring years of mistreatment as a prisoner of war in Vietnam. We know that you were tortured. Were you tortured a lot?

James Stockdale: Yeah, I think more than anybody else. About halfway through the first months, the camp reorganized itself. They weren’t sure the war was going to last, but it came down from on high, “Pull no punches.”

They got a couple of teams of torture guards and they had a special procedure. And the way it was done was to get a long iron bar and shackle your legs to it, and then the man on the back would start weaving ropes through your arms to bend them backwards. And then they — getting as much leverage as he could — what they’re doing is shutting off the blood circulation in your upper body. And then he would push, he would bend you double and stand on your back and he would pull from this angle, giving him better leverage, and then he would find—you know, it’s about over when you feel the heel of his foot in your—back of your head and he put your nose right on the cement and there you are. You’re encased in ropes. Your blood is not circulating. You’re in pain and you’re in claustrophobia. Now there’s only two ways to go. You can die or you can submit. I did that 15 times, and I don’t think anybody had that many before. I had about five within one real short period. But when we looked at the — we knew — now this took about 45 minutes to go through all this and get all that blood stopped. And we knew we had eight guys that died in the ropes. And then later when some books came out we know we had over a dozen, because these were guys that were put in those ropes even before they got into the prison. They were just in the ante way when they were taken in. So that was what we were living with.

So sometimes when you submitted you gave them information, but it was never what they wanted, was it?

James Stockdale: No. You’ve got to be an actor. Every move you make, you’ve got to have it conform to an imaginary man you’ve made up in your mind, particularly with the senior people. They had no idea who I really was.

Admiral, how did you survive psychologically? The other men you mentioned perished under the same circumstances.

James Stockdale: I don’t know. I didn’t feel like I had more vitality than the next one. I had things to do. I was alone a lot, and I found ways to talk to myself and to bolster my own morale. I was getting occasional letters from my wife, Sybil. And she would from me. She probably wrote 50 and I got six, and I probably wrote 20 and she got two or something like that.

After I came out of Alcatraz, we all came back to the regular prison. They tried to get me to go downtown. They tried everything. They would give me the ropes three times a week.

One of my original breakthroughs was self-disfiguration. I was given a lot of times in the ropes in Room 18, which is the main torture chamber of Hoe Lo prison. It also serves as kind of a ceremonial chamber when no prisoners are in there. In that, the only room in the building, a great big building with plate glass windows, and they had big heavy quilts that they drew across it. I was in there and they were about at their wits end. Two officers were working me over. Pi Ga, my torture guard, was always there to take me wherever they wanted. It was about mid-afternoon and they said, “Okay, you’ve done okay, today. Now you want to get washed up.” I knew what that meant. That meant we were going downtown that night.

On any day you could probably find a couple of international discussion groups somewhere in town and on some days probably five of them. And they would cajole Americans into going downtown. It’s not so much the location, it’s someplace in Hanoi where you’re going to talk about politics and nothing else. I never went downtown. In Heartbreak Hotel a lot of prisoners only had access to this showerhead that was in a regular cell with two cement seats or beds. But this was dedicated to showers, they didn’t have anything else to do. So you walked in, and you went between these beds, and then you saw the spigot and pretty soon the water started coming out, and you were to take your clothes off, and he handed you the soap and the razor and slammed the door because he had other errands to do.

As soon as I could I got my head wet and lathered up, I started with that safety razor, just cutting a track down the top of my head that I judged would make it impractical for them to take me downtown. He came back to the peephole and I ducked down, just showing him my behind, which is all he could see because I was stooped over. I didn’t realize that I was bleeding so bad. And then he came in and grabbed me, grabbed my arm and he knew he was in trouble, too. There was blood running down my shoulders and there were secretaries in the courtyard that we went by and they were looking. That was the headquarters prison of the whole country of North Vietnam so they had offices and they had everything you can expect. He took me back into this room and boy, those two officers, they said, “How dare you? How dare you?” I just got down in the position for the ropes and he said, “You have no right to take the ropes.” I knew I was getting him screwed up. Finally, they said, “I got it. We’ll get a hat and we’ll take you down to the press conference with a hat on.” So as soon as they locked the door, I looked around for something else to do damage to myself with, and I saw the old toilet can that had been there for years, and I knew every chunk of it, but that was infection and one thing — and then I said, “Well, what’s wrong with this mahogany stool?” and bang, bang, bang, bang, and the secretaries across the hall wondered what the noise was and they started shaking the door. I didn’t — couldn’t see them. But by the time they got back my eyes were closed and there was no question about it. They couldn’t do anything and said, “What do you want me to tell the commissar?” I said, “You tell the commissar the CAG decided not to go downtown tonight.”

And they went out and then they gave me — you know, then through that — other times I’d used other devices. They told me, “We think they’re going to put you in the mint pretty soon.” And that was kind of the end of the line. There was an old privy outside, and we had this signal system. You could take a vertical wire — the outsider wouldn’t even realize it was up there — and if you moved it this way, that meant there was an old bottle under that sink. If you had a message for Stockdale, he would know that he had a message in the bottle. If it looked like it was booby-trapped, you’d just push it back. There was even a position for if it was okay.

So I was down there and I was exchanging notes and getting things done and then I had kind of got a nice note from a guy and I — but we were — what we were using for paper and pen was tough toweling that was sort — it was the idea of toilet paper and rat manure. You’d lick it and you could print right on it and get another piece. And so a voice said — and I was careless on this.

He sneaked up under the door, and it was kind of a complicated thing but he said, “What are you doing?” I said, “I’m reading these letters my wife sent me,” which was authorized. They would leave letters. And he said, “No, your hand was moving.” Uh-oh, I knew it. Well, then he ran and he got the turnkey and they came in and they got me out and they told me to put my hands up — this is the typical prison shakedown position. In the meantime, I had had sense enough to put it in the crotch of my pants. I did that because I concluded — and I think I’m right — that there’s a great connection between farm boys in Illinois and farm boys in rural Vietnam. They have a sense of propriety against intruding in other people’s private parts. As far as I know that’s true. I don’t know, because I didn’t have it up there well enough. As I was walking back it rolled out of my pant leg and then they had it.

There was something in the air. I don’t want to make this too mysterious, but it was kind of a dark and dreary night. As they walked me over to the other side of the camp and put me in a little privy-like place I’d never seen before that’s just full of cobwebs — it would only accommodate one man — and I think they were just doing something to get me out of that camp so that I knew I’d go in Room 18 the next morning. And the man came in with leg irons and he put them on me and they were squeeze irons, built to put pressure points on your legs so you couldn’t sleep that night. And I looked down there and he was, so help me, weeping, and not out of sympathy for me I’m sure, but I marked that down in my book. And then the next morning, when I was taken over to the other place to get the torture started for that day there was a couple of other people weeping. And I said, “Old Ho Chi Minh probably died last night.” I’d been unsuccessfully accosted to give them information. I could hold it back from the particular crowd that was working with me that day, they were kind of halfway friendly people. Something was wrong. The whole country was going bananas. Later that afternoon, I was just lying down on my roll, assuming that the day was over, and this guy named Bug, who was a snotty officer, he said, “Get on your feet! Tomorrow is the day we bring you down.” That meant I would succumb.

And he said, “This country is in mourning. There will be dirge music in the streets tonight. Ho Chi Minh died last night and we’re in mourning.” Well, I’d anticipated that. And then they didn’t let me lie down. They put me in a chair. They said, “Put him in a chair with ropes on his arms and traveling irons for his feet.” Traveling irons were what you got so you could go to the bathroom in the night. I was depressed. I said to myself, “God, maybe I’m the problem here instead of the solution.” I had said, “Here’s my orders. Remember: B-A-C-U-S: BACUS.” It could be tapped out. “B” means do not bow in public. “A,” stay off the air, never talk into a tape recorder or a microphone. “C,” don’t kiss them good-bye when we go home. “U-S” might be seen as United States but what it really means is “Unity over Self.” That was the first order. I put out dozens of them but that was the instruction. I said, “Maybe I’m the problem, because there had been people who were killed in the ropes.” And then I just said, “I do know one thing. I’ve got to change the status quo because I’m going to be dealing with a different country tomorrow than I was yesterday. And who knows what’s going to happen? They may go bonkers.”

And so I said, “I’ve got to change the status quo,” and with that I got off from my traveling irons and went over and shut off the light, pulled back these blankets, and exposing the plate glass window, using the palm of my hand, which was relatively free — I had enough freedom there, to get the long shards, pull the curtains back, turn on the light, get back in my chair and sit down and just start going like this. And, first of all, I started getting blue blood and I said, “Where is the blue blood coming from? We’ve got to get some red blood.” And so I said, “I don’t…” I said to myself, “Is this right? I don’t know but I know I’ve got to…” my hands — I had run out of ideas and I had to explore the future. You wouldn’t think I had a future if you saw me. I passed out in a pool of blood.

Did you want to die, Admiral?

James Stockdale: No, I don’t think so. I just knew I had to do something, and I had kind of a hunch that there might be some opening here. I went unconscious. I had a feeling that ever since I’d started this self-defacement they had a suicide watch on me. About two in the night somebody screamed “Eow,” and I think that was the suicide watch. I think he looked through a peephole and saw me in that pool of blood in front of my chair.

I was groggy and I really had to be slapped awake, but the room filled up with soldiers and the doctor and some officers and a lot of guards. They were cleaning the room. They were like they were ashamed of it and they were sweeping the floor and putting fluid on it that smelled like something in a funeral parlor. The guards took my clothes out and washed them. The officers were nasty, but they couldn’t figure out what to say. Finally — I don’t know the time of night, maybe 3 or 4 in the morning — they brought in a cot, and then they brought in a chair and they put a soldier in the chair, and he put the rifle across his knees, and they let me lie in the bed with a pillow and I passed out. “Boy, this has been a day!” I looked up at those walls and they’re all covered with geckos. You see them on all of the walls in Southeast Asia, and they’re moving around and they snipe at one another but, God, I looked up there and to me all the geckos were bisecting their friends! I knew I was hallucinating. I almost laughed.

The next morning the door squeaks open and I look out and it’s the commissar himself. He sat down and he said, “Stockdale, do you want a cup of coffee?” I said, “Yes.” I don’t think I had leg irons on. I went over and sat down across from him, and he said, “What happened last night was a catastrophe.” And he said, “You know I sit with the general’s staff. A report will be written. It may adversely affect me. It might even adversely affect you. I can’t say. But…” he said, “You will not stay here. We will put you back in that little place where the doctor will attend you until all traces of bandage and scars as best we can arrange it are gone.” Well, I was out there from September to almost Christmas and then I went back. Things had happened. I was completely out of communication there. I found out two things. One, nobody had ever been in the ropes since I cut my wrists, and secondly, the commissar had been discharged. So from then on the life was never the same. It wasn’t happy, but I shut down that torture system and they never wanted it brought up again.