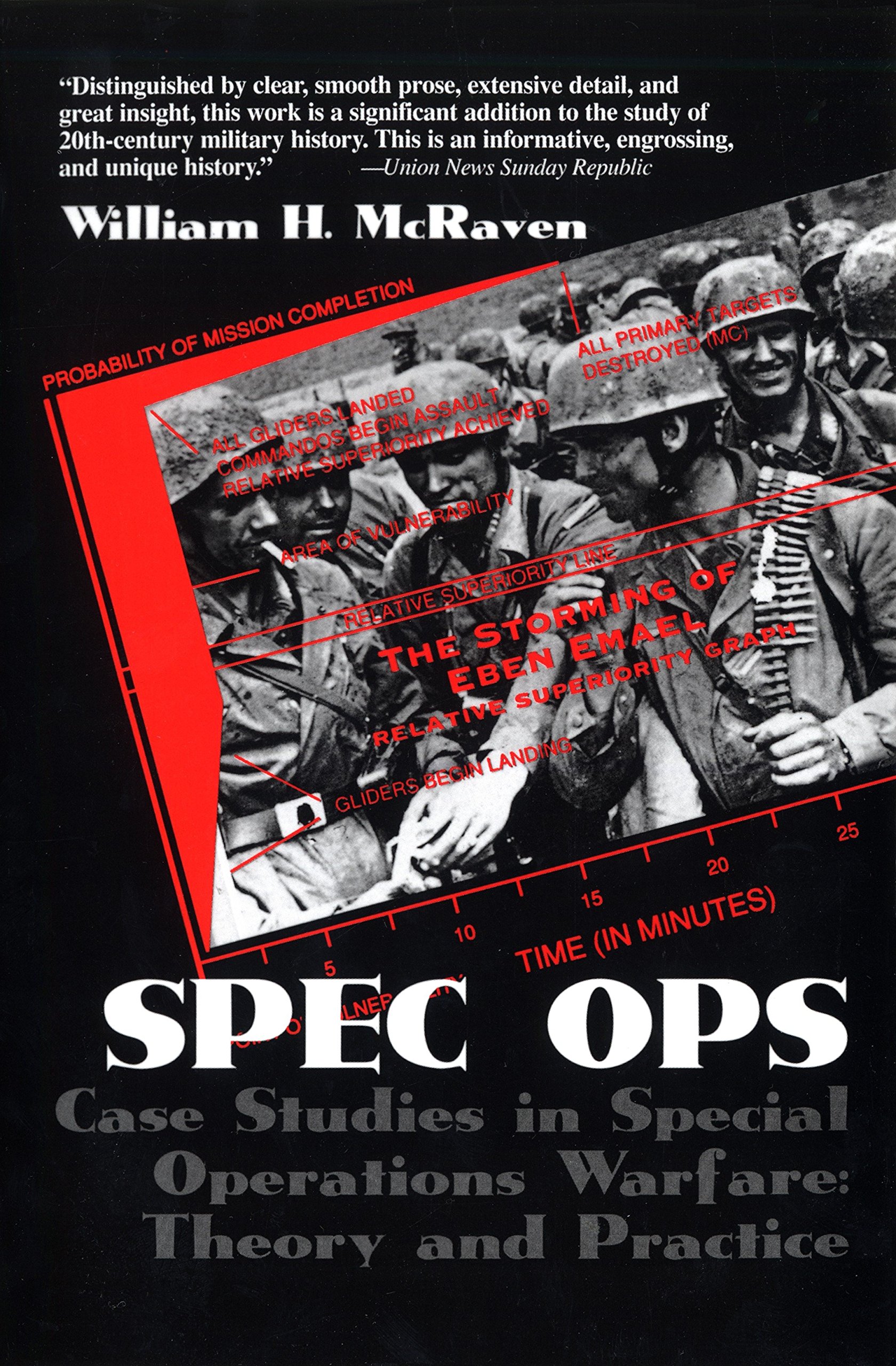

You were at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey when you wrote The Theory of Special Operations, a remarkable thesis that has been widely read. What was the thinking behind that?

William McRaven: I had an opportunity at Naval Postgraduate School to do some thinking about special operations. And more importantly, I had an opportunity to travel to Europe and interview some of the great special operators of World War II and also kind of post-World War II. Most of them were still alive. They were in their 70s — early 70s to early 80s — and the folks I interviewed were still very sharp and remembered the missions they went on as though they were yesterday. So having an opportunity to sit down with these phenomenal officers and enlisted who had been part of some of the great operations in special operations history was just incredibly educational for me.

But I remember as I was interviewing Herr Witzig, who was a German officer, about the raid on Eben-Emael, which was a very famous German raid into Belgium that secured a very difficult fort with a small number of folks. But in the course of my questioning for him, he said, “Well, you are developing a theory here, yes?” And at the time I was actually just trying to cull out the principles of special operations, much like the broader principles of war. But when he touched on the idea that you were developing a theory, I thought, “I think he is on to something.” So I went back and really spent about another six to eight months to figure out how do I take the principles and turn them into a real theory about why special operations succeed. Not just the principles, but why do they succeed, how can you — not analytically, but kind of intellectually — take a look at a special operation ahead of time and say, “Look, are we going to achieve this thing I call ‘relative superiority’ in a timely enough manner and long enough to be able to accomplish the mission?” So it was a wonderful, passionate effort on my part to just kind of find this out. And fortunately, the book got a lot of traction with some of the younger officers, and I’m pleased to see that it got such a wide read.

The public perception of special operations may be that it’s full of mavericks and is the Wild West of the military. But you’ve said in previous interviews that SEALs may follow their rules closer than anyone. It’s about doing things differently and creatively, but within the rules. Could you tell us about that?

William McRaven: Absolutely. Again, I think you are right. There is this perception that — it’s not to say we in the special operations community don’t have a swagger. You have to have a swagger, you have to be confident. But when you sit down to do a mission, you have got to do the detail planning. You have to do the detail rehearsals. You have to be physically fit and mentally prepared. And that doesn’t happen by accident. That happens through very difficult training and appropriate preparation. So anybody’s belief that you can go do a complicated special operation in a cavalier manner has never been in the business. To be a really good special operator, you’ve got to care about the details.

But there is a creative component.

William McRaven: Oh, absolutely.

The more pressure there is, and the more there is at stake, the more ingenious and creative you have to be.

William McRaven: You do. When we look at a problem, the reason people call special operations forces in is because they looked at it initially as a conventional problem and they said, “Well, you know what, an infantry battalion can’t go do this, or an air strike can’t go do this.” So they have eliminated a conventional approach and now they have come to us. So then it really becomes, “Okay. What is the creative solution to this problem, and how can I apply what skill set we have differently than the infantry battalion or the air strike?” So you absolutely have to be creative, but I think you have to be creative within a framework. If you try to be too creative, the laws of war –the frictions of war — will bring you down just like they will in an infantry battalion. So again, you have to understand where your talents are, where your expertise is, and within that framework be as creative as you can possibly be. So for example, when I did the theory and the thesis, the Germans for example used gliders to get into Eben-Emael. They used gliders because they were quiet and they knew that the Belgians wouldn’t hear them coming. They could put a lot of men in gliders and get on the target quickly.

When was this?

William McRaven: This was at the beginning of the war as the Germans came against the Belgians as part of the initial movement into Belgium and then into France. The Italians used little mini-submarines to go against the British shipping in Alexandria. So the thought that special operations are cavalier isn’t true. Do we have a creative aspect? Absolutely. You have to be creative. You have to look at what tools are out there — mini-submarines, gliders, parachutes, whatever it is — to get you to the objective. And then you have to be right on target with the talented people you bring.

In your book you talked about security, simplicity, repetition, speed, surprise, purpose. Perhaps surprise is the most creative part.

William McRaven: It is. Because the rest of the stuff is, I don’t want to say pro forma, but the issue is you have to be able to get on target, and you have to be able to do that before the enemy knows you’re there. So when I talk about, in the thesis, this point of vulnerability, when you look at an operation, you want to bring that point of vulnerability — the point where the enemy knows where you are and the enemy can stop you from getting to the target — you want to bring that as close to mission success as you can, as close to the target as you can. So the further that point of vulnerability is away from when you’re on target, the more difficult your mission is going to be. So you want to close that gap. You close that gap by surprise. You gain surprise through things like, again, gliders or mini-subs or ships that look like different ships, as the British did during the raid on St. Nazaire. So this is the creative piece. How do I get to my objective before the enemy knows I am there in a manner that we know will be effective, but generates that surprise that now, once I am on target, your force is probably going to be better than the enemy’s force? But you have to get there, because if the enemy spots you two minutes away, or three minutes away, their ability to engage you — and you not being able to get to target — changes the whole dynamics of the mission.

Some people have an image of creativity as a sort of muse that alights on your shoulder. It seems that in this case perseverance and discipline are integrally wrapped up with creativity.

William McRaven: I think this gets back to the military model: the details have got to be part of the framework of the mission. I will give you a case in point. The British went after a ship in Norway during World War II and they used actual small dry submarines. Mini-subs, basically.

There were three men in the mini-sub, and they were going after the German ship, the Tirpitz. And the Tirpitz was up in a fjord far into Norway, and they knew that if they could get these mini-subs with these large mines on the side of them, they could come up the fjord, drop these mines underneath the Tirpitz and destroy the Tirpitz, so that it couldn’t get out and wreak havoc in the North Atlantic. Well, the problem was, in the course of the planning for the mission, they knew that they were going to have to tow these mini-subs across from Scotland over to Norway. The problem was that was a long rehearsal and they didn’t want to do the full rehearsal. So they only tested it for a couple of hours, because the guys in the back of the mini-sub would get so sick because it was kind of porpoising up and down underwater. So they said, “We know this is going to work. We don’t have to test it for the full 24 hours or so.” Well, because they didn’t test it for the full 24 hours or so, three of the six submarines never made it, because the line broke, because after 24 hours it was pulled to a length where it just couldn’t withstand the strain and it broke. They would have known that had they tested it for the full 24 hours. So back to the discipline and the detail point. Yes, they were very creative in using a mini-sub to be able to get to the Tirpitz, but they didn’t have the discipline at the time to do the full rehearsal, and that requires discipline. Even though you know you’re going to be miserable during the rehearsal. If you don’t find that out before the real mission, then that part of the mission is probably going to fail, which it did in that case.

I don’t want to talk about the creative aspect in terms of the arts, because I know that is a lot different, but for a military mission you have to be able to balance the creativity with the discipline or you become cavalier. And that is not what you want.

We have the examples of Mozart and Beethoven, who were incredibly creative within a very, very clear structure.

William McRaven: Right, absolutely. I wouldn’t compare what we do to Mozart and Beethoven, but the point is well taken.

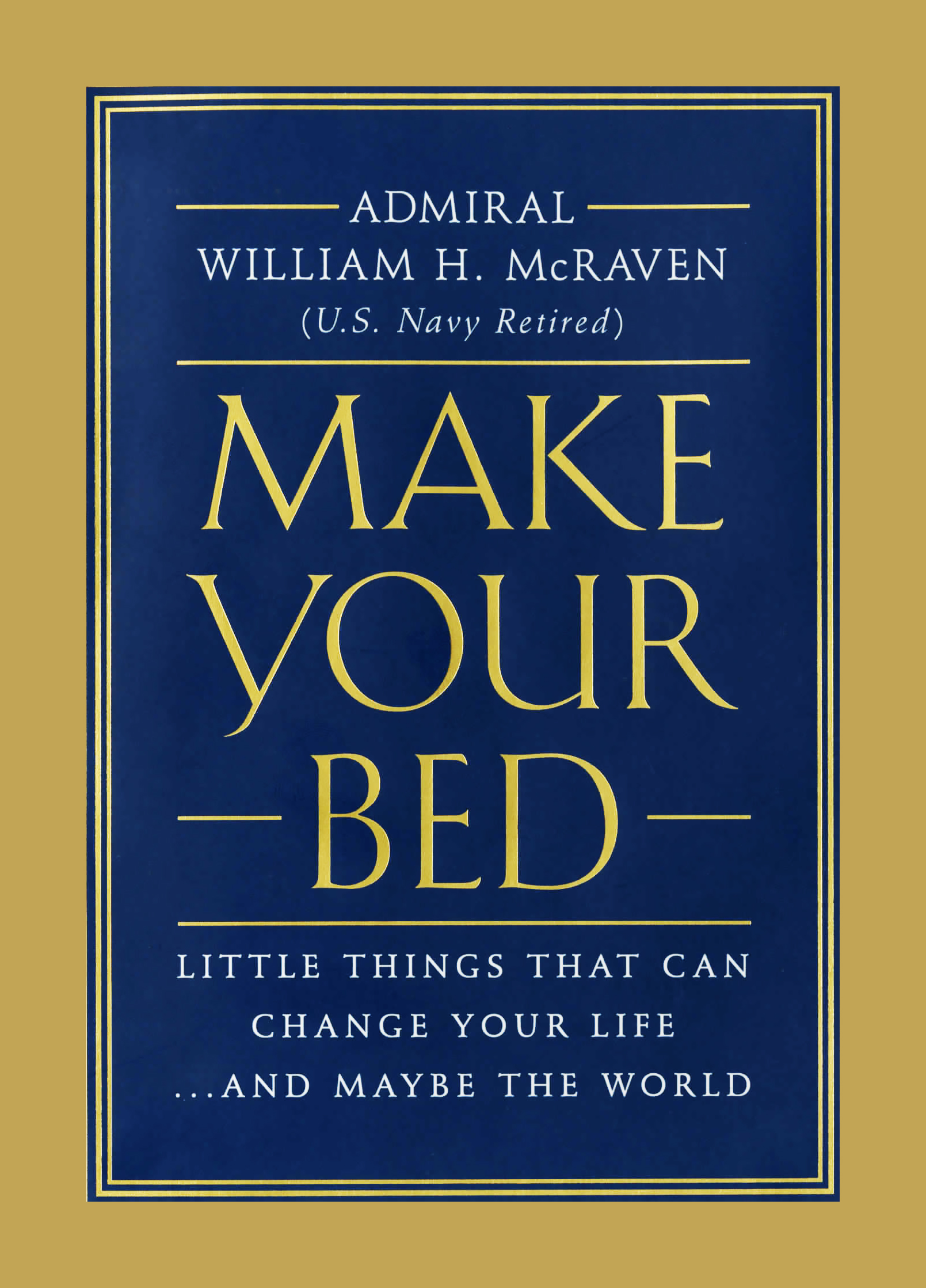

The world knows more about your training as a Navy Seal than they might have as a result of the commencement speech you gave at the University of Texas that went viral on the Internet. Could you tell us a little bit about your SEAL training and the impact that had on you?

William McRaven: SEAL training is like a whole life crammed into six months. The purpose of the training is to weed out those both weak-minded and weak physically before you really even begin the hard SEAL training. So there is a lot of demand placed on you physically, but there was also a lot of demand mentally. They put you in situations where you are either not going to succeed or you’re not going to succeed as well as you thought you were going to succeed. So they will, for example, they used to play a little bit of mind games. They would say, “Okay, we are going to have a four-mile run on the beach.” And as you were closing in on that last couple of hundred meters, they would go, “Oh no, this isn’t the finish line. The finish line is another couple hundred yards down the beach.” And there were a lot of guys who went, “Come on, I was just coming to the finish line.” “No, the finish line is further on.” So you learned that maybe there is no finish line, and you learned how to deal with failure, and you learned kind of what is really inside you, because you were tested physically every day. You were cold, you were wet, you were miserable, and you still had to perform at a certain level.

Once I got through with basic SEAL training — we call it BUDST, Basic Underwater Demolition SEAL Training — I walked away with a belief that there wasn’t anything else that I was going to encounter in life that was going to be any harder than the last six months. And I will tell you, for the most part, that’s been true. I have never been colder, I have never been more miserable, I have never been more tired. So that is really where the training, I think, helped. But it’s true of a lot of military training, whether you’re an Army Ranger — Ranger training is very similar — Special Forces, Green Beret training is very similar, Air Force Special Tactics training is very similar. So any time you are tested I think you learn a lot about yourself, and I think I was all of 22 years old, so I learned it early.

A couple of things came out in your commencement speech at the University of Texas. One is that small things we do can be very important. Could you tell us about that?

William McRaven: The one thing they teach you in the military is really the value of small things. As I mentioned in the commencement speech, I use the bed as an analogy, but it was a little bit of everything. So every morning you had a uniform inspection, and the military uniform that we wore, you had a brass buckle and you had to polish that brass buckle until the point where there were no smudges, that there were no corrosion, that the brass buckle was perfect. And you would spend hours every night polishing that brass buckle, and then, immediately after the inspection, they would have you go jump in the surf zone and now your buckle would be corroded. But the point they were trying to teach you, much like the bed, is the little details matter. Because the brass buckle and the bed later equated to your weapons system. So when we would go out on operations, your weapon — and in the case when I first started, we carried an M-16 — and you would go out and you would be on an operation all night long. You would come back at about 4:00, 5:00 in the morning. And you are really tired, again, you are cold, wet, and you are tired and all you want to do is take a shower and get in bed. But what’s important is you have to stop and clean your weapon first. And you just can’t do a cursory cleaning of it, particularly not if it’s been in the salt water. You’ve got to do a very thorough cleaning. And if you don’t do that, and then the next morning you go out on another operation, now your weapon is corroded and it might not work when you get in combat. So the point is, the little things matter. And that really does transcend into planning, for example. A lot of people ask me about special operations, and there is this belief that it is the bravado and kind of the cavalier approach. What I learned very early on is that’s not what makes our operation special. What makes our operation special is the level of detailed planning and rehearsals that we do, so that the hard things become simple when you’re in a combat situation. You learn that in every military organization from the very beginning, whether it’s how you spit shine your shoes, how you polish your brass buckle, or how you make your bed. The details matter.

Isn’t there also an aspect of overcoming your fears? You had to do some dives in the dark waters and in cold waters.

William McRaven: You’re absolutely right. You’re being tested across the full range of your emotions and your fears. One of the training evolutions is to do what we call a ship attack.

As you get up underneath the ship, as you approach a ship, there’s a little bit of light above you. You can see it when you are underwater. But once you get close to the ship, the ship blocks out all the light, and the target for a ship is the keel, the center line of the ship. And as you get under there — one, ships have machinery, so there is a very deafening noise as well which can disorient you very quickly. So you have to maintain your composure, you have to be calm, you have to move to the center line. You cannot see anything. So it is so black you literally can’t see your hand in front of your face, so everything is by feel. And you also know that under a ship there are suctions which could, in fact, pull your facemask off or do some things. So you have to be very calm, very composed as you are making your way to the objective, even in a training environment. So this is another aspect of the SEAL training that’s very important is learning to keep your composure when things are very, very difficult. Again, that is something that will weed a guy. A lot of guys could do the physical part, but when they got to this part that — while it was still physical — it was much more mental. It’s about, “Don’t be afraid under a ship. Be calm, take care of business and then get out and then keep moving on.” So a lot of guys struggled with that and didn’t make it through that part of the training.

When you were a young man undergoing SEAL training, you might have stopped and thought, “I don’t have to do this. I could be doing something else.” Where did you get the strength of character to pursue something so difficult?

William McRaven: The young men that join the SEALs or the Army Green Berets or the Rangers, there is a sense of adventure about them and there is a sense of confidence about them. Ninety-nine percent of the people that come through training have played in some sort of sport. So we had, in my class I had a lot of swimmers and rugby players and water polo players and football players. And so you have a level of confidence, you have a level of a sense of adventure. So you come into a situation like that and there is — and of course when you’re young you’re a little bit cocky. You tell yourself, “There’s nothing I can’t do. I am the best at what I’m doing.” So you challenge yourself, and I think it’s true of any endeavor. So I’m not sure that there was this great strength of character. I think it was, fortunately, being young. You come in probably a little bit overconfident, but you also come in physically strong. And you have gone through a process in high school or other places to really build up your, again, your skill set, your sense of adventure, your sense of character that allows you to get through training.

Were you athletic, too?

William McRaven: I was. I was very small in high school, but I did play football and I ran track in high school, which was really where I found my niche. But I played basketball, football, baseball. That’s how kids my age grew up, particularly in Texas. We played every sport imaginable. We didn’t have video games, so every day you were out doing something. I learned that early on. As I mentioned, my father was an incredible athlete, actually as was my mother. But my father taught me football, baseball, basketball, tennis, a little bit of everything.

You guys liked to hunt together, too, didn’t you?

William McRaven: We did. Dad was a big deer hunter and dove hunter, and we spent a fair amount of time together. I remember he would get home from work around 5:30 in the evening, and if it was during dove hunting season, fortunately we were in an area where it was a couple-mile drive to the dove field. So during dove season we spent a lot of good, quality time together. Or during deer season, he had leases every year and we would go out, sit in the blind and hunt deer. I was very fortunate to have terrific parents and terrific siblings. My sisters have been fabulous as well.

Let’s talk some more about your family and childhood. We understand your father was also in the military. Could you tell us about that?

William McRaven: He was a World War II fighter pilot, World War II, a little bit of Korea time. He joined the Army Air Corps in 1940. He had played professional football with the Cleveland Rams, and as he began to see kind of the storm clouds brewing, if you will, he and five guys left the football team and traveled out to Los Angeles, as I understand, signed up to join the Army Air Corps. And then, by 1940 he was in the Army Air Corps, and then when the war broke out in ’41, he went over to Europe and actually fought in cross-border between Europe and France. He flew actually Spitfires — which was a British plane — flew Spitfires in supporting the bombers as they did the cross-channel operations. Then he was down in Sicily and Salerno. So a pretty active World War II career. And then he had a 26-year career in the Air Force.

So you grew up with the idea of military service.

William McRaven: I did.

That must have been influential.

William McRaven: It was, and it wasn’t just my father. All of his friends were all World War II veterans. So you had this Greatest Generation effect on, I think, both me and my sisters. We had family friends like Tex Hill, and Tex Hill was a very famous fighter pilot during World War II. He had 28 confirmed kills, both as a Navy fighter pilot and then he also was part of the legendary Flying Tigers. We had friends from all walks of life within the military that all retired kind of in the same area. So I was raised from this Greatest Generation. They had a tremendous impact on me.

What about your mom?

William McRaven: My mom was born and raised in Texas and she was independent-minded, but she was kind of a woman of the ’50s in terms of her style. She was very gracious, a good Christian woman, but she also had the classic starched hair and she smoked and had her cocktails at 5:00. But she was just a fabulous mother. My father was kind of the historian and the math guy, and my mother was very much about the arts. She taught me poetry and taught me my love of reading and writing. It was a good balance between my mom and dad.

Do you remember particular books that meant a lot to you as a kid?

William McRaven: I was raised more on poetry than I was on books. My mother gave me the classic 101 Famous Poems and I can remember, on at least a weekly basis, we would go through it and read one of the poems. Her favorite poem was Rudyard Kipling’s “If.” “If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs and blaming it on you…” My father also liked Teddy Roosevelt, so I read a lot of books on Roosevelt as well. It was this kind of confluence of poetry and biographies that I was raised on.

Your sister once said that it was possible that James Bond had an influence on you.

William McRaven: Well, recognizing that I grew up in the ’60s. I was born in 1955, but my really formative years were in the ’60s. Of course James Bond came into vogue in the early ’60s so I saw every James Bond movie. I wish she hadn’t made that comment, but now it is out there in the public forum and the answer is yes. I was absolutely a huge James Bond fan. And John Wayne. I watched every John Wayne film and every James Bond film.

Thunderball in particular?

William McRaven: Thunderball! I love Thunderball because I actually wanted to be a marine biologist initially, but I think Thunderball got me a little bit off track because I liked the action scenes in Thunderball. I started scuba diving when I was 13 years old, so Thunderball to me was very exciting because of all the underwater scenes. I think that kind of helped propel me in a different direction than being a marine biologist.

You majored in journalism, didn’t you?

William McRaven: I did, but probably for not the right reasons. I started off in pre-med, did not do so well in pre-med. And then I went to accounting, did even worse in accounting. I went to journalism because I knew there were good-looking women in journalism, so that was something I figured would be a good pursuit. As it turned out, I could write. Writing came fairly naturally to me. And while I struggled in pre-med, and I struggled in accounting, I got into journalism and we were writing ten-page papers three or four times a week and I loved it. I enjoyed writing. It was, again, a skill that came relatively easy to me. So the courses were easier than the ones I had been in, and I had a phenomenal time over the next two years, my last two years at the University of Texas. I was actually in news reporting so I learned how to do what I think is the best writing, in terms of it had to be clear, it had to be concise, you had to check your facts. And all of those things served me well when I later joined the military.

Especially in military command, communication is key, isn’t it?

William McRaven: Absolutely. People always ask me, “Was it of any value to you?” And I said absolutely. Being able to convey your ideas, whether it’s in a speech or a briefing or just a discussion, is critically important for any walk of life, but particularly in the military.

Going both up and down the chain of command?

William McRaven: Absolutely. Actually more so going down, because you have to be able to instill a little bit of leadership in the troops, and you do that by conveying your ideas clearly and concisely so they understand what we call “commander’s intent.”

A journalist for the Dallas Morning News, with tongue in cheek, once asked you what was it about the terrifying world of journalism that caused you to take refuge in the serene, undemanding life of a Navy SEAL.

William McRaven: Journalism to me was really, I hate to say this, but it was kind of a means to an end. I was trying to get commissioned, and you had to have a certain grade point average to get commissioned. As I said, I struggled early on with pre-med and with accounting, so my GPA before my final two years was pretty low. Once I got into journalism, I actually did pretty well. I brought my GPA up, and that allowed me to get commissioned. I never really thought I would use my degree in journalism, although it turned out to be very, very helpful.

Is it true that a Green Beret helped inspire you to become a Navy SEAL?

William McRaven: He did. I don’t know his name, but he was dating my sister at the time. This was probably — I want to say either the early ’70s or the late ’60s, ’69 or maybe ’70. And he came to the house and what was interesting back then — because the Vietnam War was going on — most Army officers didn’t wear what they call their Class A, so their standard uniform. But my sister was getting ready, the doorbell rang and I think I was 16 or 17 years old I guess at the time, and he came to the door and he was wearing his Class As with his green beret. Of course, I had seen the John Wayne movie, The Green Berets, and I was enamored with the Green Berets. So he came in and we began talking. But at the time my mother was trying to get me a Navy ROTC scholarship. So in talking with this Green Beret who had done a number of tours in Vietnam, he said, “Well, if you want to be in the best there is in the Navy, you need to go be a Navy SEAL.” Well, back in 1970 I had never heard of Navy SEALs. Frankly, most of the public had never heard of Navy SEALs. But when I had a Green Beret telling me to go be a Navy SEAL, I figured that was pretty good advice.

Why do you think he said that instead of the Green Berets?

William McRaven: Well, he knew that I was lining up to have a Naval ROTC scholarship. That had come up in discussion. So I was heading down the Navy path, rather than the Army path. I think if I had been heading down the Army path, he probably would have convinced me to go be a Green Beret.

Were your parents supportive of your taking the military career so seriously?

William McRaven: Oh, absolutely. I think they were very pleased. Actually, my mother kind of moved me towards the military. She was looking for a way to get me through college. I was in high school, I really wasn’t thinking about the next step. She kind of set me up for success with a Naval ROTC scholarship. I think they were very pleased. I think my dad would probably rather have had me go in the Air Force, because he was an Air Force officer, but I chose the Navy path and they were pretty pleased with that.

I don’t think they fully appreciated when I became a Navy SEAL. I know my mother didn’t understand what I was doing. Because in the Air Force back then, the special services officers were those that took care of the golf course and the gymnasiums and did those sorts of things on an Air Force base. And I remember about eight years after I had become a Navy SEAL, I was home and my mother was having a small party and I overheard a conversation with her and one of her friends. And one of the friends, “Well, so what is Bill doing now?” And my mother took kind of a deep breath and she said, “Well, he’s in special services.” And I could tell the tone in her voice was, there was a little bit of disappointment. And so after the party was over, I said, “Mom, what do you think I do?” And she goes, “Well, you told me you were in special services.” I said, “No mom. I’m in special operations.” She said, “Well, what’s the difference?” Okay, so when she found out I was in special operations, I think that created a level of anxiety that I didn’t anticipate. I said, “Well, I’m jumping out of airplanes, and I’m diving underwater, and I’m blowing things up. And I think she would have appreciated it if I would have stayed in special services rather than special operations.

Cleaning up golf courses?

William McRaven: That’s right, taking care of golf courses.

Your mom probably did prefer the other scenario.

William McRaven: Absolutely. My mother passed away in ’86, so I was a Navy lieutenant at the time. She really never understood what I was doing, I think. It was, “Okay, he is some diver or something in the military.” But in 1986 when she passed away, nobody had heard of Navy SEALs. We were a very small community.

So your mom might have preferred you to be looking after golf courses, but did your dad live to see your future career?

William McRaven: He did. And in fact, when I became a Navy captain, which was equivalent to an Air Force colonel, which he had been, we did the promotion ceremony down in Tampa, Florida, and my father was able to come down. The insignia are the same, they are eagles, so my father was able to pin his eagles on my collar. Unfortunately, a year or so later he had a stroke and was never the same again, but it was a terrific moment for both of us.

You’ve said that if you try to do difficult things in life, you will probably experience failure fairly often, and it will be painful. There was one point in your military career that didn’t go so well. Could you tell us about your experience of losing a command in the early ’80s?

William McRaven: I was a brand new Navy lieutenant, and I went to the premier SEAL team of its time. The commanding officer and I had a disagreement about how things would be run and he was the commanding officer. He essentially fired me, removed me from my position as a commander of a SEAL element and it was a very difficult thing to deal with. I was confident enough in my own skill set that I thought I was good enough to do this job. And then you find that either: one, you are not good enough, or two, the circumstances surrounding you didn’t allow you to continue on, which was my case.

Can you tell us more about that? Was it a personality conflict? This officer has described himself as something of a loose cannon.

William McRaven: He was a very flamboyant officer. He had served in Vietnam as an enlisted man — became a mustang, as we say — he was later commissioned. And he was brilliant in his own way and I harbor absolutely no ill-will against Dick Marcinko. But I was young, and he was trying to shape SEAL Team Six at the time. And I came in with probably a little bit more of a conservative belief in how we should run operations. I believed in kind of the basic tenets of good order and discipline because I had learned that — growing up in the earlier part of my SEAL team — good order and discipline made a difference. It made a difference in the morale of the men, it made a difference in the professionalism of the men, it made a difference in the operations. And Dick Marcinko’s approach was a little bit more, I don’t want to say cavalier, but he had a little bit different approach in terms of how he looked at both the relationship of the men and the relationship of the operation. So it was a little bit of a conflict of personality and a conflict of how business gets done on the SEAL teams. But again, he was the commanding officer. So in a military organization, at the end of the day the commanding officer makes the decisions. And again, I don’t fault him for the decision, but it was one of those things I had to deal with personally when I went on to another SEAL team. Because people knew that I had just been essentially relieved of that command position, and that’s not a good thing in any institution. So you have to be able to — it kind of summons up your personal courage — and decide that, “Okay, things didn’t go so well. I’ve got to prove that I’m as good an officer as I think I am. I have got to continue on.” The option to quit was always there. It’s a volunteer force. I could have gotten up and left.

Did you consider that?

William McRaven: I never did. I wanted to make sure in my own mind and in my own heart that I was capable of doing what needed to get done. Frankly, I look back on it as probably one of the more pivotal moments in my career, but I’m glad I went through it. It allowed me, as I became more senior, when other officers that worked for me had those problems, I had an entirely different approach about how I dealt with it than how I was dealt with during my time there with Dick Marcinko. But he was a good officer, he did good things in terms of building SEAL Team Six and we actually have a good relationship now.

And you did get another chance.

William McRaven: I did get another chance. I went from SEAL Team Six to SEAL Team Four, which was another SEAL team on the East Coast. They immediately gave me a SEAL platoon. For a young officer, that’s an important part of your career building and that platoon went very well. After that, I never looked back.

What was the state of Naval special operations back there in the 1980s? The world didn’t know a lot about Navy SEALs back then, and there weren’t all that many of them either.

William McRaven: When I started, I think we had somewhere in the neighborhood of 200 officers and about 500 enlisted men. So to give you some perspective, today we have over 500 officers and 5,000 enlisted men, so we have grown quite a bit in the Navy SEALs. So back to when I joined, it was a very small community. You kind of, at one point in time if you were on the West Coast you knew every officer on the West Coast. If you were on the East Coast, you knew every officer on the East Coast and every enlisted man. Very small, tight community. But frankly, back in the ’70s when I came in, and then as we went through the ’80s, we had learned a lot. The Vietnam generation kind of raised my generation, but we didn’t have a lot of equipment. We didn’t have a lot of money to train. It was post-Vietnam, so there was this belief that maybe we didn’t need special operations anymore, so the amount of funding and available training opportunities for the SEALs went down dramatically until about the mid-1980s. And then in the mid-1980s everything changed. We had the Reagan buildup, we had the establishment of the U.S. Special Operations Command, and with that came more money and we began to train more. And across the board, not only for Navy SEALs, but for Army Green Berets and the Air Force, we really got a lot better starting in about the mid-’80s.

There wasn’t much room for promotion in the SEAL program at that time, was there?

William McRaven: When I came in, in 1977, there were two Navy captains, one on the East Coast, one on the West Coast. You never had any belief that you would be a Navy captain. All I wanted to be was a Navy lieutenant, a SEAL platoon commander. That really was kind of the pinnacle of your SEAL career at the time, because after that you kind of became a staff officer. Now that is not true anymore, but back in the ’70s and the ’80s, once you got through doing your platoon commander tour, you then became an executive officer, which was more of a staff position, a commanding officer, which was more of a staff position. But I aspired to be a Navy lieutenant. And then, at one point in time I remember, about 15 years into my career, I got a call from the person that moves us around called a detailer. And he called and he said, “Hey, Bill. You’ve screened for command.” And I thought, “Wow, so I’m going to be a commanding officer of a SEAL team!” I hadn’t thought about that until the moment he called. I just kind of went — my event horizon was, “What am I going to do today? How am I going to do that as well as I can? And then when tomorrow comes, I’m going to do that as well as I can, and I’m just going to kind of keep moving forward.” And the thought of being an admiral? We had no admirals. So when I came in, nobody aspired to be an admiral. You couldn’t be an admiral. And with only two captains, I didn’t aspire to be a captain. So I have been very fortunate.

There’s a lot about your career we can’t talk about, but I wanted to jump to a few months before 9/11. I believe it was July 18, 2001. You led a jump exercise that did not go as planned. Could tell us what happened?

William McRaven: We were doing a freefall so a static line parachute is where you hook up inside the aircraft, the freefall you jump out with a parachute on your back. So I was doing a freefall operation out in Southern California outside San Diego. And as I was descending, I noticed that there was a jumper below me on my right side and two jumpers below me on my left side. And the jumper below has got — in terms of freefall they always have the right of way. So I was watching this guy over here, and before I knew it this guy here slid underneath me, so he was probably about 500, 600 feet below me and he opened his parachute. So in relative terms, he was coming up while I was going down. So as he opened his parachute, I kind of hit his parachute. It stunned me. I rolled off him. I rolled off his parachute and was a little stunned. So I pulled my ripcord knowing that I was getting to the altitude where you needed to pull it. And the pilot chute which comes out of the back of the parachute wrapped around one leg and then the risers, the webbing that is part of the parachute wrapped around the other leg and I was falling kind of head down towards the ground. The good news was that it opened; the bad news was when it opened it essentially broke me in two. So it broke my pelvis, it broke my back, it ripped a lot of muscles out. But the good news was I did get to the ground, and they came and picked me up in an ambulance and took me to the hospital and plated me and pinned me and got me back together again.

It’s extraordinary to have the presence of mind to pull the ripcord when all hell is breaking loose.

William McRaven: I think it was just an instinctive reaction. Frankly, the smart thing to do would probably have been to wait and get stable again. I was not stable as I was tumbling because I am not a great freefaller. I was a journeyman freefaller. The right thing to do would probably have been to get stable again and make sure I knew what was going on before I pulled. When I hit the parachute I was dazed a little bit, so I really didn’t know what altitude I was at. I was spinning out of control, and I couldn’t see my altimeter, so I pulled. It worked out good in some respects and not so good in others.

So the doctors were able to put you back together again.

William McRaven: Yeah, a little bit. Plated, pinned. Great doctors. When I look at the injuries that the young kids are sustaining today, mine was like a scratch. It was nothing compared to what these young kids are having to encounter or sustain today.

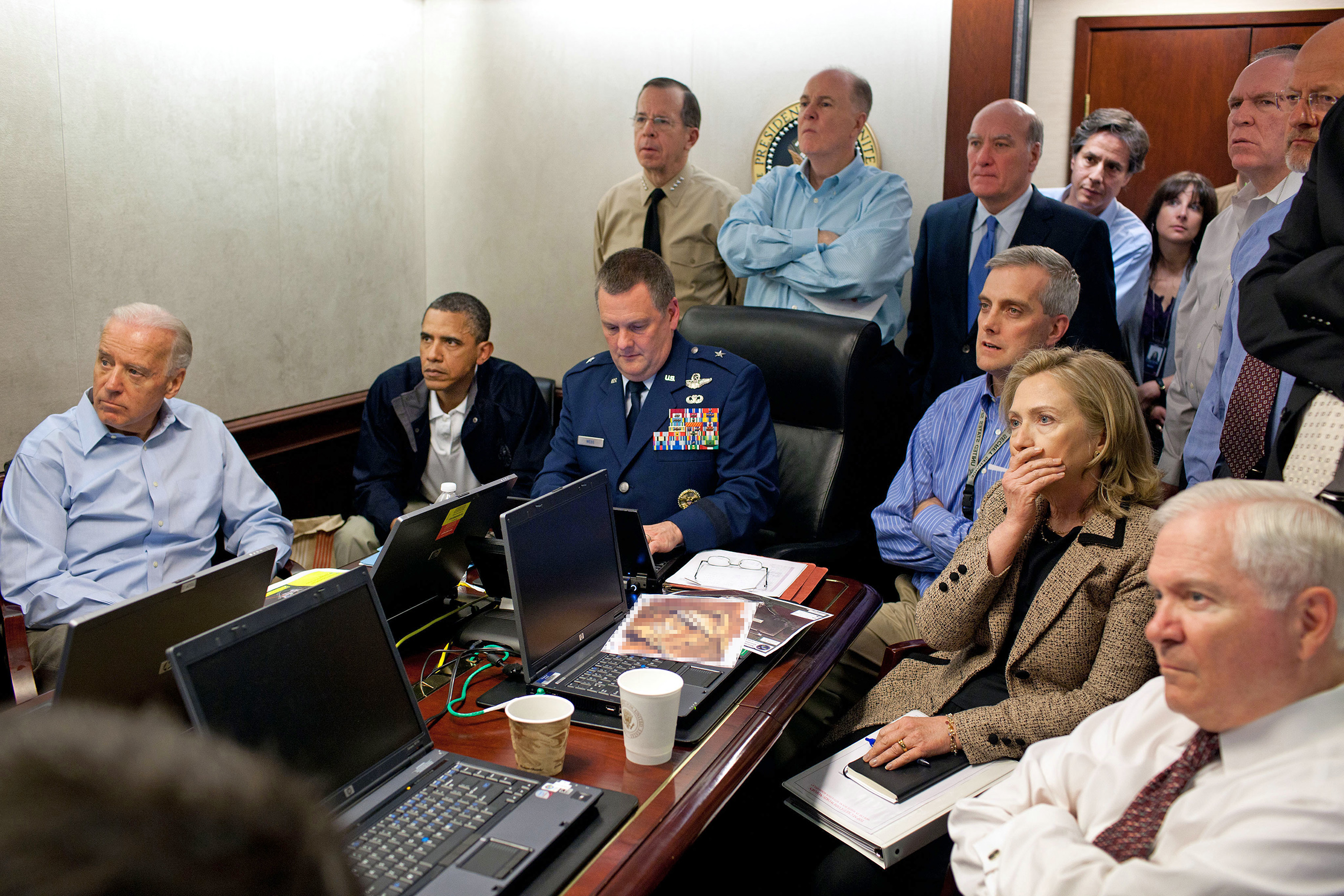

So you were laid up for a while. Could you tell us where you were on September 11, 2001, and how you perceived the events of that day?

William McRaven: We had moved a hospital bed into my house in base quarters in San Diego. So I was literally lying in a hospital bed in my living room when 9/11 happened, and I was watching it on TV just as everybody else was. I knew right then and there that the world was about to change. It was pretty obvious, because I kind of expected what we would do in terms of our reaction, but frankly I didn’t think I would have any play in it because I was still in a hospital bed and recovering from my injuries. Part of my concern as a Navy SEAL and a military officer was I’m not going to be in a position to help the nation because I’m pretty banged up. But I was very fortunate. I healed. It took me a long time to heal, but I healed enough to be able to get to the White House. Then General Wayne Downing had been selected by the President of the United States to run the Office of Combating Terrorism. And General Downing gave me a call and said, “Hey, how would you like to come work for me?” And he knew I had been in a parachute accident, and it was going to be a staff job on the National Security Council staff. So I jumped at the chance and spent two years there and had an opportunity while I was there to kind of heal. And then after that I went back to an operational unit and kept moving.

Go back for a moment to September 11. You are watching it more or less live on TV. What went through your mind at that point? How did you receive what was happening?

William McRaven: Just like every other American, I was stunned, watching the people of New York and later the Pentagon. I was watching the towers fall on TV, and trying to go through, in my mind, what the people of New York were thinking. How were they going to deal with this? To watch the people of New York and the nation come together after 9/11 and make a strong stand, and be very clear that this act of terrorism was not going to interrupt our way of life in a grander scheme, and that we were going to recover from this was, I thought, one of the most awe-inspiring moments of my life. To see the people of New York, in particular, as I watched them deal with this incredible tragedy and hold their heads high and do the right thing.

Are we going to keep having to deal with extremism, do you think?

William McRaven: Absolutely. This is a generational problem. And it requires decisive action, it requires early action. While the American people may not want to have to deal with this, what I would tell them is whether we want to or not, it is going to be out there and it is going to affect the global population and thereby affect us. So we can either deal with it now or we can deal with it later, but we are going to have to deal with it. And some people say, “Well, we can’t be the policemen of the world.” I am not sure at this point in time we have a choice. We are the country that can best deal with this, although we certainly need to build a coalition where we have willing and capable partners to go do it, I’m all about that. But where we don’t have wiling or capable partners, and there is a threat out there, then my opinion is we still need to go take decisive action and do something about it.

A lot has come out in recent years about problems at home with regard to the treatment of veterans, medically for example. Do you see breakthroughs coming in the future?

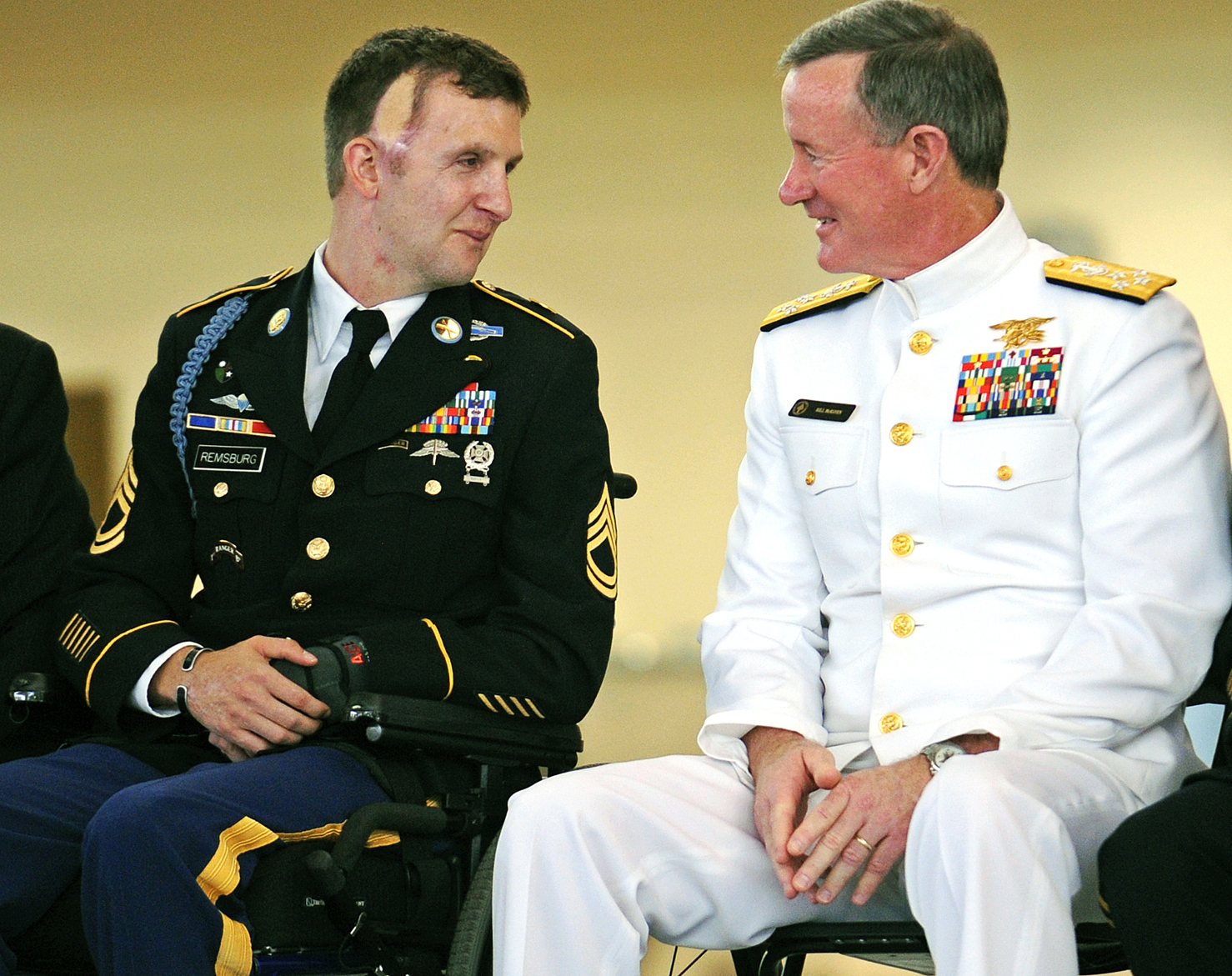

William McRaven: Within the special operations community, for the last three or four years we have worked very hard on dealing with the issues of our returning soft operators and their families. The families are a big piece of this. We started an initiative called the Preservation of the Force and Family Task Force, the POTFF as we used to refer to it.

When myself and my command sergeant major — the senior enlisted man that is with me in the command — when we went out and we began to talk to the families, we realized that there were a lot of problems out there and problems that I don’t think we fully appreciated. Even though intuitively we knew these guys had been at war at that point in time for ten, 11 years and the strain on the families and the soldiers was huge. As we began to dig into it more, we found it was a lot deeper and a lot more troubling than we thought. So we in the special operations community have put a lot of effort into a number of things. The physical aspect of this, we find, and the research is very strong, that if a guy is physically healthy, if he works out every day, if his nutrition is good, if he is getting enough sleep at night, he is less likely to have domestic abuse issues, alcohol problems, he is less likely to commit suicide or she is less likely to commit suicide. And we have had, unfortunately, our suicide rate has been a lot higher than we would have liked. So we know there is a physical component to this. There is a mental health component to this as well. And a lot of this is about taking away the stigma of, “I’m a tough Green Beret or Navy SEAL and I’m okay.” No, you may not be okay. Sit down and talk to the psychologist, talk to the chaplain, talk to a friend. Talk to somebody. Talk out your problems and then we’re going to make sure we have the people that can help you deal with those problems.

And then finally the family piece of this. It’s great to take care of the soldiers, but we need to put a lot of effort, and I think a lot of money, into making sure that the wives and the kids are well taken care of. Because it is a very difficult thing, and I have been married for 36 years, and I think my wife would echo this, and we haven’t had to deal with it near as much as these young kids have. So you think about these young soldiers that came in right after 9/11 in the special operations community, and they have been fighting continuously since 9/11. So every time they would go on deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan, their wife or their husband had to say, “What if they don’t come home? What’s going to happen?” And that stress and that strain was incredible. So now we are working to help the families and to make them resilient, to talk to the wives and the husbands and say, “You need to exercise as well. You need better nutrition. We need to figure out how you can get better sleep so you can deal with these problems. And oh, by the way, we’re going to set up mechanisms where you will know what is happening with your husband. You need to know also we’re going to take care of you and your husband or you and your wife.” So this has been an important part of this effort for my time in Special Operations Command. When I look back, I think we did a lot of good things in my tenure as the four-star at Special Operations Command, but that’s the one I take the greatest pride in is knowing that we are taking care of the soldiers and their families.

You have taken on a pretty big job, now that you’ve left the Navy, as Chancellor of the University of Texas, your alma mater. Do some of the skills that you learned in the military pertain to the rather challenging political job in front of you?

William McRaven: I absolutely think they do. The University came to me and frankly, that was one of the first questions I asked is, “Why are you interested in me? I don’t have the educational pedigree that a lot of the great chancellors and the presidents have.” But they were looking for the kind of leadership skills that I think I have learned over the last 37 years. The role of the chancellor, unlike the role of the president, is really about establishing a vision. It’s about working with all the stakeholders — so the president, the faculty, the students, the Texas legislature, the Board of Regents, the “Texas Exes” — all these various folks. And I do that today. I mean, a lot of people think that the military is: the commander gives an order and everybody moves out. Well, that’s not the way it works. Like any other large organization you have to lead people. You have to mentor people. You have stakeholders, even within the military. So in my last three years, having worked on Capitol Hill and working with the White House and working with the State Department, I understand how to build this coalition of the willing within the stakeholders and get them to move in the right direction. So in my discussion with the senior leaders on the university system, I think they understood, and that’s why they hired me was to, again, make sure the University was moving in the right direction. The university system — it’s not just about Austin, it’s about the larger university system — was moving in the right direction. And that really requires leadership and management, and I have had an opportunity to do that quite a bit over the last couple of years.

What does being a Texan mean to you? I gather you weren’t actually born in Texas?

William McRaven: No, I was actually born — my father was stationed at Pope Air Force Base and I was born in North Carolina. But we moved to Texas in 1963, I believe, so I went to elementary school, junior high school, high school and then I was at the University of Texas. But my father, who was also a transplanted Texan — my mother was born in Texas, born and raised in Texas — my father was a transplanted Texan, but he loved Texas, as did my mother. And of course, there is an aura, I think, around Texans in the sense that they are folks that believe that, “Hey, you pull yourself up by the bootstrap and you keep moving and you don’t complain about things.” And you have this attitude that things can get done if you just work hard enough and press forward. And so I believe that is true of America in general, but Texans take great pride in that. They take great pride in big ideas. They take pride in doing big and grand things. And so I am happy that the opportunity to be the chancellor at the University of Texas hopefully will give me the opportunity to do big things for the people of Texas.

At the beginning of that famous commencement speech, you quoted the motto of the University of Texas, which is very powerful, “What starts here changes the world.”

William McRaven: I thought it was a great motto. I didn’t really start writing the speech in its final form until about two days before I gave the commencement address. I had started working on a different theme about a week or so earlier, and it just wasn’t working. But I love the idea of “What starts here changes the world.”

In my remarks earlier this week at the Academy I talked about the movie It’s a Wonderful Life. And that is a Christmas classic that I grew up with long before DVDs. In the movie It’s a Wonderful Life, there is this great scene where George Bailey, who is played by Jimmy Stewart, is taken to the local graveyard there at Bedford Falls, and the angel Clarence tells him, shows him the headstone, the tombstone of his younger brother Harry. And George protests a little bit and he says, “But Harry didn’t die at the age of six. Harry went on to be a Medal of Honor recipient during World War II because he saved 500 guys on a Navy ship.” And the angel says something that, again, I think was very important for the movie. He says, “But you don’t understand, George. You weren’t there to save your younger brother from falling through the ice, and because of that, your younger brother wasn’t there to save the 500 men on the ship.” So not only — in the course of this movie — the point being you did one brotherly act that saved your brother, your brother went on to save 500 people. What started in Bedford Falls kind of changed the lives of those 500 people. So as I began to think about that. I actually went back to my ops analysis people and I said, “Look. We’ve got 8,000 people graduating tonight. So tell me what it would take to get to them affecting 800 million people. What is that?” And so my folks went by, and it was kind of simple math, and they said, “Well, in about 125 years, if each one of them affects the lives of ten people, and those people affect the lives of ten people, and etc., etc., etc., then exponentially within 125 years you have affected the lives of 800 million people.” So the fact that what starts here can in fact change the world, I think, is a great way to look at it. And as I told them in the commencement address, I said, “I saw this happen all the time in Iraq and Afghanistan, where some young soldier would make a decision, like say I’m going to go left instead of right.” Something doesn’t seem right, and as a result of that the platoon is saved from an IED, or they are saved from an ambush. And that one decision by that officer or that enlisted man all of a sudden just changed the lives, not just of the ten people or the 12 people, but of their children and their children’s children and their children’s children. So this was the point I was trying to bring at “What starts here changes the world.” The idea that one person affecting the life of one other person, or ten other people, can over time change the world.

That decision to take one path instead of another, that’s instinct. It takes a measure of self-trust.

William McRaven: It is, absolutely. Part of my discussion the other day was there are some things in life you control. I don’t know that you control the sweeping hands of destiny. I have listened to a lot of the speakers here at the Academy this weekend. It has been fascinating. And almost every one of the stories they talk about, you know, “I was planning on doing this and then all of a sudden I went off and did this.” And to me there’s a little bit of destiny in that. Someone or something that moved them in a different direction. But I said that the things that you do control are the little acts of kindness, the little acts of compassion, the little acts of courage that you can do every day. And you have no idea sometimes how that pat on the back to that soldier or that sailor is going to change their life, and then change their kid’s life and their children’s life. So you can control that and so take the opportunity — every opportunity you can — to be kind, be generous, because you have no idea what that can do for people.

The importance of the small things.

William McRaven: Absolutely, getting back to the details in the little things.

What does the American Dream mean to you?

William McRaven: I am living the American Dream. I really believe that. I was raised in a great household with two wonderful parents and two great sisters. I think what I find interesting about the American Dream is, to quote Bubba Watson, “My dreams didn’t go this far.” I never dreamed of being a four-star admiral in charge of U.S. Special Operations Command, because we didn’t have it. Earlier this week, I think it was Wolf Blitzer talking about being in the right place at the right time and then doing the right thing.

To me, the American Dream is the opportunity for me to be able to be in the right place at the right time and then do the right thing. Not once, not twice, but a lot of times that kind of moved me along this path to be where I am today. But there was nothing that stopped me. And for me the American Dream is, I look at it today — and this is one of the exciting things about being the chancellor — is I look at the changing demographics, and the changing kind of social fabric we have. And I think the human capital that we have in the Hispanics, in the Asians, in the African Americans, and in the women that are out there — give them an opportunity to get an education and it will change everything. And I have seen this firsthand in Iraq, and Afghanistan in particular, where the female population that we spent a lot of time in Afghanistan trying to get them into schools and were very successful at doing that. I guarantee you that will change everything about Southwest Asia. As the women begin to grow up and they have this great education, and you see the incredible character of women like Malala from Pakistan, it’s all about education. I honestly believe that. If we can educate our young kids coming out of high school, we will buy down fear, we will buy down bigotry, we will buy down all of the bad things if we just do a good job of educating.

Your work is cut out for you.

William McRaven: It is, but I’m looking forward to it.

Thank you, sir.