One day passes, and another day and another day and another day, and you never know when it’s going to end. You get your food. I’d be allowed out to enter a little yard for exercise. I would run round and round, favoring my right leg, and then round and round the other way favoring my left leg, and I would sing and I would whistle, and I tried to keep up my courage. And one day I hear whistling, and I can’t believe it, because it’s not just the general noise. Prison is noisy.

People screaming, screaming, shouting, doors being slammed, everybody shouting, and I hear whistling. And I whistle back, and then I hear the whistling coming and I tried out the ANC freedom songs and there was no response. And I’m wondering, “Who is it? Somebody else in solitary confinement?” And we made a connection, and it was the “Going Home” theme from the Dvorák “New World” Symphony. (Whistles.) And I hear from far away in the prison. (Whistles.) I don’t even know who it is. I don’t even know who it is. And this was a wonderful form of contact. And then I would do exercises as part of my regime, and I’m in the middle of trying to do a hundred press-ups and I hear the whistling, and I say, “No, I’m only up to 75. Please wait, wait, wait. Can’t you wait?” And then we had to kind of establish a time during the day where we would be ready for the whistling. And I never found out who it was.

Never?

Albie Sachs: Not until I came out of prison. That was months later. Her name was Dorothy. She had seen me once in exercise and she thought, “Gee, Albie is so brave.” She’d heard my name and I saw her sitting there and I thought, “Gee, that woman, whoever she is, she’s so brave.” We each thought the other was brave. I was crying inside. I was wretched. And our lives actually met up with — years later when I went into exile into England. She was there. She came there and we spoke and she married an Englishman. And years later, after I was blown up, and my like second exile in England, she got in touch with me. And when I set up the South African Constitution Study Center to prepare for a new constitution, I asked her to be my assistant. She said, “Albie, no. I’m too old.” And so I said, “No, Dorothy, you must.” And she did. And she came back to South Africa when I went back to South Africa afterwards.

What kind of relationship did you develop with the guards while you were detained?

Albie Sachs: I was very worried about myself. I thought, “I don’t hate them. If I’m a serious freedom fighter, I should hate them.” But I just saw Flicky, a guy doing his job as he saw it. “Advocate Sachs…” They called me “advocate,” like attorney. “Do you mind if I tell you a joke?” I was dying to have someone speak to me. “No, no. Go ahead.” “There was this child who swallowed a little coin and his mother said, ‘We must take him to the doctor,’ and his father said, ‘No, no, no. We must take him to the lawyer. He’ll get the money out of him much quicker.’ Do you mind if I tell you that joke?” And, you know, it was such a weird situation, that he’s still respecting me as a policeman, he’s respecting me because I’m a lawyer and treating me as a human being. He wasn’t from the security police. And I couldn’t imagine killing him or hating him. I could imagine living in the country with someone like him, who is kind of all right, you know, on a one-to-one basis. Maybe with the black prisoners he was much harsher, but I didn’t feel that. He didn’t have that edge. And when occasionally he would speak about…there was a black constable and Flicky would say to this constable, but not in a bullying way, “Fetch some water for the boss.” So I was the boss. I’m in prison as an enemy of the state trying to overthrow the state, but I was called the boss. You know, the racism just went everywhere.

At times it was quite painful that your whiteness, whether you liked it or not, followed you all the way through. Even when I was blown up afterwards, my white body counted for more than the bodies of black people who were blown up, who were tortured far more severely than I was tortured. The world, the press, the media, controlled by people — white themselves — seeing the world through white eyes. Not even maliciously, just automatically. That’s their standpoint, their point of reference. And so my amputation, my body counted for something. And then I had to think, “Well, what do I do about it?” And I said, “Well, it gives me access. It gives me a chance to speak.” The New York Times had a full page spread, “Broken But Unbroken,” with a lovely picture. At least I can be like an ambassador for all the others whose voices aren’t heard. I must use this space and opportunities that they’ve got, even if they come with a privilege, to fight for justice in our country. But at times it was painful, even in prison.

I might say I discovered years later, after democracy was beginning to come to South Africa, and I was interviewed by Anthony Lewis, a columnist for The New York Times, about my attitude to the white guards and the others, and I explained that I felt I ought to be more angry than I was. And I said, “There’s something wrong with me.” He said, “You know, I’ve just spoken to Nelson Mandela. He said the same thing. And I’ve spoken to Walter Sisulu — said the same thing — and Ahmed Kathrada, who said the same thing.” And I realized I belonged to a culture, a generation based on the values of the Freedom Charter. We were fighting against a system, a system of injustice. We weren’t fighting against a race. We were fighting for a better country, a better society. That system, which had not only oppressed and imprisoned black people in terms of their hopes and their possibilities, but imprisoned whites in fear and narrowness and inwardness and arrogance and greed. That’s what liberation meant. That’s what emancipation meant.

How did you survive your detention?

Albie Sachs: I barely survived the 90-Day detention. It was the 90-Day Law. You could be locked up for 90 days, and somebody comes to the little cell that I was in and gives me back my tie and my shoelaces and my watch. I had been without a watch for 90 days. I used to hear the City Hall clock chiming and that would give me the hours. To this day when I hear that City Hall clock chiming, I get an uneasy feeling. And on Sundays I would hear the bells, the carillon playing, and I can’t get pure pleasure from that. I get a little bit cold. I feel a sense of shock. This beautiful thing of bells playing on a Sunday, joyous bells, and I start shivering. And now I get my watch back and I go down the stairs and the station commander meets me. I go to his office and he says some nice things to me. And I get a phone call from my mother and he said, “Yes. No, he’s all right. He’s fine. He’s being released.” I’m very suspicious, and I said goodbye and I walk out of his office and I’m walking to the street and a policeman comes in and says, “I’m placing you under arrest.” So they released me for two minutes and then I’m in for another 90 days. That’s how you play with the law. I take off my tie, my shoelaces go, my watch goes, I’m back in the same cell.

And I started having some out-of-body experiences then. Very strange. I’m lying on my little cot, and I would feel Albie is lifting out, looking down on me. And I’m not a person given to a spiritual view of the world in that sense. I’m a great believer in the human personality and spirituality in that sense, but not an out-of-body experience. But I had them. They were quite, quite strong. I’m a little bit worried, but I carry on, I do my exercises, I run around the yard, I do my press-ups.

Suddenly one day they come and say, “You’re being released.” Now it wasn’t after the second 90 days, it was after another 78 days. So now I’m a little more hopeful. I get my tie back, I get my watch back, I go downstairs, I look around, there’s no policeman to arrest me again. And I put on my running shoes. I’m in the center of Cape Town. I’ve grown a big mustache. It was the only thing I could do where I felt I had some self-determination. And I ran all the way through Cape Town and through an area called Green Point, and down to the coast, further than I’d ever run in my life, about eight miles, dreaming, I’d always dreamt of, if I’m released, if I get through this, I’m gonna go to the sea. And I go down the steps, and by then my colleagues, the lawyers in Cape Town in their suits, have driven up, and they saw me there, and they’re waiting for me in their smart lawyer suits, and I’m looking a bit crazed. I was a bit crazed. And down the steps and I just flung myself into the sea. It was absolutely triumphant on the outside. Inside there was something crushed, something deeply unnerved by these weeks and weeks and months of just being on my own.

How did you keep your sanity during all those weeks of solitude?

Albie Sachs: I would try to keep myself going by inventing games, and I would sing songs, a song beginning with “A,” “Always.” “Because,” “Charmaine,” “Daisy,” go through the alphabet. It’s quite an interesting collection of the hit tunes of October 1963. And my favorite was “Always.” “I’ll be living here always. Year after year, always. In this little cell, that I know so well, I’ll be living swell, always, always.” And I would sort of waltz around, singing to myself and be amused with the fact that this Irving Berlin song— picked up by Noel Coward, who wrote comedies of upper middle class manners — was keeping alive the spirit of this freedom fighter in Cape Town. “I’ll be staying in always, keeping up my chin always. Not for but an hour, not for but a week, not for 90 days, but always.” And then it’d be “Because,” and “Charmaine,” and so on. I would try to remember the states in the United States of America. I had two arms then, so I could count on ten fingers, but — and I would begin with all the A’s — and I couldn’t mark down. And I think I got up to about 47 once.

I won’t mention the names of the states that I didn’t remember when finally I got out and I looked at the map. I had a towel, it was a checked towel, and I would use pieces of orange peel to play checkers on the towel. But it’s boring playing against yourself. Your left hand knows what your right hand is planning. I would watch ants. There was a caterpillar once, it became very exciting, and suddenly disappeared. It was just a kind of activity.

After I’d been in a couple of weeks, the only book I had was the Bible, and I would ration myself to read a couple of columns every day. Not too quickly, because I might be in for years, and I didn’t want to feel stale and saturated. So I’d read the Bible for a certain period. I would do my exercises, food would come. I would pace around, and I would try to construct some system during the day. And one day the station commander comes in and he’s waving a piece of paper. He said, “If they’d listened to me, this would never have happened.” I don’t know what he’s talking about. He gives me the paper, and I’m reading, and I can’t read across the page, so I’m reading down in columns. My eyes are going down — but the sentences — and it says, “In the Supreme Court of South Africa, Cape of Good Hope, Provincial Division, in the case of Sachs vs. Russo…” Hey, that’s me! “Before Justices…” — it was Banks and Van Vincent, or Van Vincent and Banks — “…it is hereby ordered that…” and I’m reading, “…that the applicant be allowed reading matter and writing material.” I couldn’t show my joy. Wow!

Until then I’d been in a rage against the judges, against the legal profession. Being picked up and put into solitary confinement without access to lawyers, without a trial, without charge, indefinite detention without trial. How can that happen? They’re doing nothing? And I turned on my colleagues, and your emotions get very exaggerated when you’re in solitary confinement. And now they were the most marvelous people who had ever been on the whole earth. Fantastic. The legal system, rule of law, even in these dark circumstances. That saved me.

That suddenly I got books. And then, what books? What do you choose? And they wouldn’t let me have my friends send in books in case there was some secret code. So I had to order from the local library, and it amused me no end to think of this young policeman going into the library and asking for Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past and imagining the librarian. I was never able to read it actually. It was too intense, too introspective. But I read Moby Dick and I read Don Quixote, two books that to this day are very powerful in my memory. Two marvelous, magnificent books that I’d never had the time to read. And I particularly enjoyed Don Quixote, especially the second volumes where Cervantes himself had been in prison. And he wasn’t writing about this crazed person pursuing futile honor. He was writing about this brave idealist who kept being knocked off his horse, and he’s down in the dust, and Sancho Panza comes and picks him up and he gets back onto the horse and he goes and he’s knocked down again and he gets up. And of course I identified totally, totally.

I’d always imagined the librarian thinking, “My vocation is made if a policeman comes in and asks for Don Quixote, even if he can’t pronounce the name properly, and asks for Moby Dick. It’s great to be a librarian!” I told that story at a world conference of librarians in Durban, a couple of years back. They were very moved. Sadly, the actual librarian — they knew who it was — he’d died in the meanwhile, so I was never able to meet him.

How did your second detention come about?

Albie Sachs: Two years later I was picked up again. By then, half of my clients had been picked up and things were much rougher now. And the investigation was much tougher, and sleep deprivation was being used as a major mechanism of breaking people down. And I’m locked up and it’s not, “Will you answer our questions?” And I would say, “Depends on what the questions are.” And they would say, “We can’t tell you what the questions are…” and it was a game, “…unless you tell us what you’re willing to answer or not.” Now it was just, I’m seated at a table, they work in relays. They bang, bang, bang, bang for like 10 minutes, and then total silence for 45 minutes. And then they go out and another group comes in, and shouting and shouting, shouting at me for ten minutes, and then total silence.

Were they able to detain you longer the second time?

Albie Sachs: It was now called the 180-Day Law. Later on, it became the Terrorism Law. The word “terrorism” was used to justify just locking us up, and we were fighting for freedom, for democracy. But the label was used to justify keeping us in indefinite detention without trial. And they went through the afternoon, through the day, into the night, deep into the night.

I asked for food at one stage, and I remember them smoking as they gave me the food — and I’m convinced there was something in it, and it emerged afterwards they were using chemicals to break down your resistance. And by early morning, I’m feeling myself getting weaker and weaker and weaker. And my body is fighting my will. So it’s not even them anymore. And they’re working in relays, there were about eight of them, and they’re taking turns, and they can sleep and come back. And the head was a Colonel Swanepoel. “Rooi Rus” (Red Russian) they called him. It’s like he cultivated ugliness. I don’t think how people appear is significant about them at all. But it was as though he liked the fact that he had short, cropped, reddish hair and bloodshot eyes and a thick neck. And heavy ham-fisted hands which he would slam onto the table, and a bellowing voice. And he was notorious. People had died — I knew that — had died under his interrogations. And then, bam, bam, bam, screaming and shouting and start banging the table, then total quiet. And eventually I feel my resistance going.

I say, “Albie, you’ve got to manage your collapse. It’s coming. Your clients had sometimes held out for two, three, four, five days and when they broke, they broke completely.” And so now I’m thinking about it, how I can control. Eventually, early in the morning, I just toppled off the chair. I’m lying on the ground and I see all those shoes coming. And I hear the excited voices, black shoes, brown shoes, and they’re all shuffling around me, and I’m just lying inert, and water comes pouring down on me and my hair gets matted. And I’m lifted up, and these Swanepoel’s heavy fingers pushing open my eyes, pushing them open, I closed them, he pushes them open, I close them, he pushes them open. And eventually I just sit and I collapse again, and the same thing happens a few times, and eventually I just sit and I’m going through my head, I’m going to say something. What am I going to say?

And I think it was about midday or early afternoon, I indicate that I’m going to say something. And they get the paper and I say, “I’m making this statement under duress, after being kept awake right through the night into the morning, water being poured on me.”

I’m sitting in the chair feeling absolutely horrible. It was the worst moments of my life, by far. I’m humiliated and I say, “I’m making this statement under duress…” and Swanepoel is writing it all down. And I describe the circumstances, being kept awake, my eyes bring pried open, water being poured on me. He’s written it all down. And then he starts asking me some questions, and I’m fencing, and he says, “Why is it you only mention people who are dead or out of the country?” And I just ignored his statement, and it’s stale stuff. I’d been out of the struggle for two years anyhow since my previous detention. But I was saying something, I was speaking to them. And our principle was you don’t say anything to them. You give your name and address and nothing more. And I felt totally degraded. He said, “We’ll be back. We’ll be back.” And I noticed he was like shuffling papers around, and he gets me to sign certain pages. And afterwards I realized that he’d left out the page with the opening statement, “I’m making this under duress.” And I feel even more humiliated.

A day or so later — somebody was smuggling in messages to me, in a thermos flask, in fact — and there’s a message to the effect that somebody else had been locked up, an architect, and had been through similar experiences, and his wife saw him and, and he was like a ghost. And he’d whispered to her what had happened to him, and she’d gone to court with that information and got an order restricting the security police from continuing the interrogation. And I wrote the second most important legal document I’ve written in my life, and I include working on the Constitution of South Africa. And a tiny piece of paper in the note that was smuggled out, saying what I’ve just explained to the camera now, in just a few words, that it could be used in evidence in his case. But the fact is, they didn’t come back for me, so it did save me from further interrogation. And I’m sure the intention was to pile it on, pile it on, pile it on, break me down completely. So though I ended up not giving away any information of any value, I still feel something inside me was broken, some strand of dignity and self-possession, and I’ve never got over it, never got over it. There’s some humiliations and pains you carry with you. You get on with your life, you manage, you do things, but you can’t say, “It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t count.” It counted. It was worse than being blown up, much worse then being blown up. The attack on my mind, my spirit, my dignity, much worse than the attack on my body which came many years later.

What brought about that release, when you were released the second time? And then what drove you into exile?

Albie Sachs: They actually wanted me to be a witness, in a trial of somebody who’d been through that whole thing, and he saved us from being called as a witness because he made various admissions in the court and we were all released. This time, when I came out of the prison, my friends were expecting me to run to the sea again, and I just shook my head. I said, “Take me home.” I was restricted, another banning order. I couldn’t leave Cape Town, I couldn’t go outside of a white area in Cape Town into what was called a black area. I couldn’t go to a school, I couldn’t be published, very severe restrictions, but it wasn’t house arrest. I was restricted to paradise, because it had Table Mountain and the beautiful beaches. And every Sunday I would climb the mountain and it was so important for me, I would feel free, because if they were following me, I could look down the cliff face and see. So I’d have five hours of freedom, and that’s one reason why I’m such a strong believer in the green movement. Somehow the mountain represented more then just a safe place. It was nature. It was the world that we’re being touched with, the earth, the sands, the rocks, the plants. And come rain, come shine, every Sunday, I would climb.

One day I went up with a psychiatrist friend of mine — and by the way I’d been introduced to Freud through all this because I couldn’t understand why is it so difficult to be brave. There was something inside me that wanted to collaborate all the time with the people who wanted to destroy me, and I was searching for it, and I found there was a thing called the unconscious that everybody has. And you’ve got to be in touch with the unconscious to understand a lot of your behavior. And I read through volume after volume after volume of the collected works of Sigmund Freud. I still remember that light blue paper of the Tavistock series. Page one to page 400, Volume 2, all the way up to the letters. And I got stuck in my unconscious for years. I had trouble getting out of explaining, “When I walk, why does my left foot go in front of my right foot?” There was nothing that just happened. Everything had to be predetermined, explained.

In any event, my friend, Professor Lynn Gillis, and I — he was a great mountain climber — we went up one side of Table Mountain, and on the left was Devil’s Peak. And I said, “Lynn, I’m going up Devil’s Peak,” and I went up, I came down, we climbed Table Mountain. We walked right across the top, we came down and I said, “Lynn, I’m going up Lion’s Head.” So these three mountains in one day. I was totally exhausted. He got really worried when I came down exhausted at the end of it. And he told me about what he called “Türschloss syndrome,” the “closing door” syndrome that elderly males often suffer from. You feel you’re losing your virility so you go through extraordinary feats of physical activity to prove that you’re still a macho guy. I was only 31, but he was absolutely right. It was, for me, desperately trying to rescue something of an inner youth through physical activity. I was very, very defeated.

I had met Stephanie Kemp who’d been, as it turned out, in the same prison cells I’d been in, and I was asked by an attorney to defend her. She was being charged with sabotage. And I said, “Please, I can’t. I identify so much.” “Just go and speak to her, give her some courage. When it comes to the trial we’ll get someone else.” Well they did get someone else to be the senior lawyer. Meanwhile I’ve fallen in love with her. We didn’t mention anything. We didn’t touch. We just spoke about the case and a bit about her past and sense of betrayal. But we were in love across the table, and she was sentenced to some years imprisonment, released. She came out to warn me that they’re coming for me again, that was my second detention. I still remember her saying, “And I was in that prison cell, and I got so angry with you because they all told me, ‘Why can’t you behave like advocate Sachs?’ And that pompous stuff you wrote up above the cell door, ‘I, Albert Louis Sachs, am detained here without trial under the 90-Day Law for standing for justice for all.’ Couldn’t you say it in less legal language?” And of course, even when I was writing that, I was careful not to say anything that could be used in evidence against me. I also wrote “Jail is for the birds” on top of the cell.

When I said good-bye to her and first time I shook her hand when she went off to prison, I just knew destiny had brought us together. She came out, we met, we carried on, developed our relationship a little bit. She being followed by the police all the time. We went down to the beach one day, and it gave me some pleasure to know that the big, heavy security officer in his suit was sitting out in the boiling sun while we were eating ice creams down on the beach. But we couldn’t even be together, and the choice was going full-time underground — there was no underground existing, I’d lost my courage — or leaving the country and asking for a permit to leave, which was another humiliation. And we decided to leave, and that we would meet in London and we would marry.

So how did you feel when you finally left South Africa for England?

Albie Sachs: In those days you traveled by boat. This is 1966. You didn’t travel by plane unless you were super rich or a prime minister or something. People were throwing streamers and everybody was happy. Lots of South Africans longed to go to Europe. And the boat would go, “Wooooo, woooo!” and my heart is going, “Woooo, woooo!” and I’m laughing and appearing very jolly and happy. At least I’m going to be free of the arrest without trial, sleep deprivation, living in a country that’s so racist and ugly, and where it’s hard even to fight back. But inside me there was a terrible, terrible heaviness.

We get to London, and all I wanted to do was lie on Hampstead Heath and watch the kites flying. It’s soft grass and kites flying, and you’re not going to be arrested. Part of it was quite marvelous, but part of it was also very humbling and very, very sad. I’d asked them for a permit to leave. I was stateless. They gave permission to leave on the basis you never came back. You committed a criminal offense if you tried to come back. And it took me years and years and years to recover my courage.

I read. I could catch up on my reading. Oh wonderful, wonderful! The History of Science by J.D. Bernard. Always wanted to read that. The Origins of Chinese Civilization by Joseph Needham, I’d always wanted to read that. Nothing to do, no pressure, no money to earn. Just to read, read, read. And then I managed to get a scholarship to go to Sussex University, do a Ph.D.

I wanted to write about this strange thing, the South African legal system. It was so extraordinary. On the one hand it allowed me to be thrown into prison, tortured by sleep deprivation. It made the majority of people carry these documents. Millions — literally millions — of Africans were prosecuted all the time for not having their documents in order. We had the highest rate of judicial capital punishment in the whole world. Kids were beaten, thousands of them, as a form of punishment for juveniles. At the same time you could sometimes use words like “freedom” and “justice.” You could get something through the court. You could expose your torture. You could be heard with some degree of dignity, there was some little open space called the courts. How could these things be reconciled? And my whole thesis was based on that, and the book Justice in South Africa emerged from that. And it was a very fascinating story for me to learn the origins of the implantation of a modern legal system. To learn about African justice in traditional African society, where capital punishment wasn’t used. Where the families would be brought together, where there was strong systems of rationality, where everybody in the community could engage in questioning the witnesses to get at the truth. I felt a little bit reconciled to what had happened to me. I had a Ph.D., I got a job teaching international law at Southampton University. They took me on because I was a foreigner and they thought that meant I was qualified to teach international law. And teaching everything — criminal law, criminal procedure, criminology, family law, contract law, law of tort — because I wanted to get material I could take back to a free South Africa one day.

But I was always down. Stephanie and I married, we had two children, absolute joys to us. I had books published.

I had a book, The Jail Diary of Albie Sachs, my first book, which was converted into a play and put on by the Royal Shakespeare Company and broadcast by the BBC. I even went to the play one day. There was an American tourist sitting next to me, and I was dying to nudge him and say, “You know what?” And some stupid sense of dignity made me feel, you know, that’s a bit cheap, and I’m sorry now, it would have been a nice story for him. And it was marvelous the way they spoke. I mean the actors, British actors, were tremendous. And when I was sitting in jail I used to imagine a play by me being put on at a theater in England. Somehow applause from an English audience in theater, that was the highest applause in the world you can get for anything. And here I’m actually sitting in the theater and people are applauding, not me but the play.

David Edgar did a most marvelous adaptation, and I did quite a lot of broadcasting and I wrote. My Ph.D. was converted into a book called Justice in South Africa, and it won some prizes and was well received. And then years later, I wrote a book called Sexism and the Law. It was the first book on the way the legal system, as a system, had kept women out, denied them the right to practice as lawyers. The way the judges had used the word “person” to say, “a person means a male person,” so that they’d even distorted the English language to keep women from voting, from practicing as barristers, from doing a whole range of things that men could just do. That was my contribution to British intellectual life. And it was published in America, California University Press, but they wanted an American counterpart and I met, through that, Joan Hoff Wilson, and she did the second part of the book. We hadn’t even met and I said, “Dear Joan, you don’t know me. Your name was given to me by somebody you don’t know either, but this is my manuscript. Can you do the American part?” She wasn’t a lawyer, she was a legal historian and she did the most marvelous section. So this was the first book in the world I think on sexism and the law. And I’m happy to say that many other books have followed and I’m sure improved on it.

But I still wasn’t happy. I would sometimes say, “Even when I’m happy in England, I’m unhappy.” I loved London. I’d take people around London. I went to shows, I heard music. I had really good friends there. I loved teaching at Southampton University. I discovered modern dance, contemporary dance, so many things, but there was a deep sadness inside me. And I remember when we used to have ANC meetings, they’d always be in drafty little halls with broken windows. I’d often be wearing a heavy overcoat and there would be nice soft seats. They would be old-fashioned halls that you didn’t have to pay very much for. And you’d get up, and the seats would all clatter, clatter, clatter. And we’d sing “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” and people would raise their right arms with a clenched fist salute. And I couldn’t raise my right arm. It wasn’t a decision on my part. I just didn’t have the courage, I didn’t feel that strength. And I’d be the only one in a room with maybe 20 people, maybe 50, maybe 10, without giving the salute of the organization. And then I went to Mozambique in 1976. I’d been teaching at the University of Dar es Salaam during one of those long English summers. You finish marking your exams, and I was able to teach a whole term in Dar es Salaam without missing a day of work at the Southampton University, and have a week left over, during which I went to newly independent Mozambique.

We’d heard about Mozambique — Samora Machel, FRELIMO, the Front for Liberation in Mozambique. They declared independence, June the 25th, 1975. It gave a huge fillip to the struggle in South Africa. People now started using the word viva. “Viva! Viva!” Viva this, that and the other. In South Africa, they took over the Portuguese word, “A luta…” they would say, “…continua,” (the struggle continues) from the Mozambiquan struggle — became used in South Africa, and I wanted to see this country. The minute my foot touched the tarmac of the airport, I knew, this is where I’m going to be happy. It was the light, the vegetation, the people. That separation from a context that you’d grown up in, involuntary, that gets to you. I was back again. I was back in Africa. I was close to my country. The energy. The problems were my problems.

I had very hard days in Mozambique afterwards. I came to work there afterwards at the law faculty in the university. Things were very hard for most of the time. We used to queue up for rations of rice and bread and occasionally eggs, and some butter, cooking oil. You could get some fish from the market, you get some fruit from the market. But we stood in line like everybody else. We were very proud to be working as equals. I had to learn the Portuguese language. The legal system was very, very different from anything I’d ever known. And there was an enormous confidence. Wow! They were so proud, and rather disdainful of the ANC. “Why don’t you fight like we did? It’s taking you so long!” And I felt at times lonely and marginalized, which I have done many times in my life. But I sort of hung in there. But even when I was unhappy, I was happy in Mozambique. I loved these beautiful trees with purple petals — jacarandas — and the petals would just fall down onto the ground. By then, unhappily, my marriage was in ruins.

I got a beautiful, filigree sort of a bracelet and I picked up these, these petals and flowers and, and I sent them to Stephanie. We were both desperately unhappy. I wrote her a long lovely love letter of what we’d meant to each other, what we’d been through in South Africa — what I wanted to say, instead of arguing about money and the children and this, that and the other — and I posted it. I waited very anxiously for the reply. A week passed, and two weeks. Then I just got a postcard and it said nothing about it, and I snapped. For me it was over. It was over, it was gone. I put everything into that letter and then… Not even a few days later then that, I get a letter from her saying, “Dearest Albie, your letter’s just arrived. We had a postal strike in England. I didn’t get it. I’m so sorry about the card that I sent you. I don’t think we can get together again. I don’t think so, but I appreciate what you said.” But I’d snapped, I couldn’t put it together again. I’ll leave it at that.

It’s hard when your marriage finally breaks up, even if you’ve been unhappy for a long time. and I felt it very strongly and I couldn’t understand why. I’d met somebody. We shared our beliefs, we shared danger and hopes and aspirations. We loved each other and we agreed on philosophy. We have two marvelous children. We agreed on what’s good for the children. We didn’t fight over money, outlook, the world, politics. Our tastes were very similar in music, art and books. And yet we just couldn’t get on.

Maybe every relationship has three big elements. There’s the element of destiny, there’s the element of passion — which was physical — and there’s the element of daily living. For us, destiny was just overwhelming. It was historical circumstance. In and out of prison, sharing dangers and aspirations. It was totally overwhelming. The passion was okay, and we kind of managed, and living was a disaster. The simple little things of how to eat, and getting in and out of bed, and just daily habits. Obviously that touched on something deeper in personality, and it was very, very sharp. I remember we were angry with each other for about six months, really angry. And then suddenly it kind of came right, and happily, Stephanie and I are close friends. We’ve been through a lot together. When I remarried, Vanessa and I both felt she should come to the wedding. It was a very small wedding and Stephanie was there.

How do you think you were affected by living in Mozambique?

Albie Sachs: Mozambique did something very special for me. I remember going to a big meeting at the football stadium. It was one of their national days, and I was right up at the top there. And a little thing of people said, “Here comes Samora Machel! There’s Samora!” And I couldn’t work out who amongst the different people was Samora Machel until he started addressing. And he would sing, and the people would join in the singing. And then he would give a viva. “Viva povo unido do Rovuma ao Maputo!” Long live the people united from the Rovuma in the north to Maputo in the south. And 60,000 arms went up, and my arm went up. My arm went up for the first time in years, spontaneously. Mozambique gave me back my courage.

The spirit, the feeling of this great endeavor — to transform a world, and people would emancipate themselves. I got it there. I went up with what we call “the Mozambique Revolution.” I came down with it, because it couldn’t be sustained. You couldn’t do it just on endeavor, just on slogans, just on good ideals. You needed systems in place, you needed to develop your economy. Your economy couldn’t be separate from the world economy. The Cold War was on. South Africa and then-Rhodesia were undermining and sabotaging in all sorts of ways, and it ended up with what appeared to be such a powerful idea of bringing everybody together, uniting everybody behind one party, FRELIMO, overcoming race, overcoming tribe, overcoming regional divisions. It left something out: space for opposition, for diversity. It just wasn’t there.

Mozambique was extremely important for me. I was back in Africa, with the problems of Africa, the energy, the song, the music, the grace, and I got my courage back. It was such a powerful idea. Unite everybody in a poor, underdeveloped, fragmented, formerly colonized nation. You bring them together around one central organization — the Front for Liberation of Mozambique, FRELIMO — that’s anti-racist, that’s anti-tribalist, that is part of the emancipation of all oppressed people throughout the world. The unity becomes such a source of strength, and it was very, very powerful.

We would queue up. We were short of food. We would get our rations of rice and cooking oil, occasionally fish, sometimes meat, sometimes eggs, occasionally butter. But we felt very proud — intellectuals, people from outside — in the country, all sharing for the sake of developing this one underdeveloped country that is coming together with its own personality. Great art, beautiful dancing, a sense of pride in being who they were and not a colonized people any more. But one thing was missing — space for opposition.

Many people ask, “Why is it that the ANC became, effectively, the key instrument in promoting possibly the most advanced progressive constitution for an open democratic society in the world?’ The theme of pluralism runs all the way through the constitutional order, pluralism based on total respect for human dignity, and a basic equality for everybody. But why the importance of freedom of expression, of having opposition parties? Many people ascribe that to the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Communist states and so on. Those things were important, in terms of the historical setting in which South Africa achieved its democracy. But the most important thing was our experience living in neighboring African countries, seeing at first hand the advantages and disadvantage of different political systems, and there wasn’t space for opposition in Mozambique. Opposition went underground. It got picked up in the Cold War by — I’m sorry to say — the CIA, and the South African security, and Ian Smith in racist Rhodesia in the earlier time, and we were beleaguered. You would hear guns going off at night. You couldn’t leave Maputo except by airplane for years. Before that we could travel by car anywhere and everywhere. I visited nine out of the ten — or ten out of the eleven — provinces. But now we were surrounded. Refugees were coming in, and you just had a sense, if there’s no scope for opposition, the opposition becomes violent, and the country gets torn apart. We had to avoid that when we got to South Africa.

While you were in Mozambique, you began to prepare for eventual freedom in South Africa. You began drafting human rights guarantees as a model code for a democratic South Africa, didn’t you?

Albie Sachs: Yes. It wasn’t just me. I was part of a very big ANC team, and I worked very, very closely with Oliver Tambo, who was the president of the ANC in exile, who had an enormous influence in my life. It’s no accident that our little son is called Oliver. He was working in Lusaka, Zambia, and there’d be a weekly flight. One day he phoned up, and I’m quite excited. Oliver Tambo, President of the ANC is phoning! I had been working as a law professor at the Universidade Eduardo Mondlane. The law faculty was closed down. I’m now working for the Ministry of Justice. I’m doing a lot of research. I’m reading, thinking, writing in Portuguese. To this day, sometimes I’m searching for a word, and the Portuguese word comes to mind before the English word. And he very politely and quietly asked me if I’m getting on with my work, my health, how things are happening in Mozambique. I’m wondering, “What do you want? What do you want?” And he said could I possibly come to Lusaka for an important project. If it would help, he would phone President Samora Machel to make it possible. And normally, in the ANC, the message would come saying, “Comrade Albie, you’ve been appointed to go to Greenland for a conference next Thursday. Catch the plane and prepare a 25-page paper.” That was the normal way. The President would say, “If you’re free we’d appreciate it very much.” And of course, when he said that, you said, “Yes, please. Please, I’d love to come.” So I flew to Lusaka about a week later, very curious, and again come to his office and he’s asking me politely how I’m getting on. What is it?

And he (Oliver Tambo) said, “We’ve captured a number of people who were sent from Pretoria to destroy the organization. And we don’t have any regulations about how they should be treated. The ANC is a political organization. It has an annual general meeting in terms of its statutes, and elects its leadership. You pay your subscription. You agree to the aims and objects. Political parties don’t have provisions for locking people up and putting them on trial and deciding what to do with them. Can you help us?” And possibly the most important project — legal project — of my life emerged from that. He said, “It’s very difficult, isn’t it, to know what the standards are for treatment of captives?” In a rather cocky way, I said, “Well, not so difficult. We have international instruments that say no torture, inhuman or degrading punishment or treatment.” He said, “We use torture.” I couldn’t believe it. ANC — fighting for freedom — we use torture? He said it with a bleak face, and that was why he wanted me in there because what to do about it? The security people had captured these rascals who were trying to blow up the leadership and introduce poison and do all sorts of terrible things. They were beating them up. I didn’t know at the time. I didn’t know the details. They did emerge later, but he knew the details. And so we prepared our whole document, which was nothing short of a code of criminal law and procedure for a liberation movement in exile, without courts, without police force, without prisons. But how to deal with those people. The host country said, “It’s your problem. Our courts are busy enough. You deal with it.” So we had to establish a code of legality, and a concept of fundamental human rights. Fundamental human rights. No torture, no abuse, no ill treatment, whoever they are, whatever they’re trying to do.

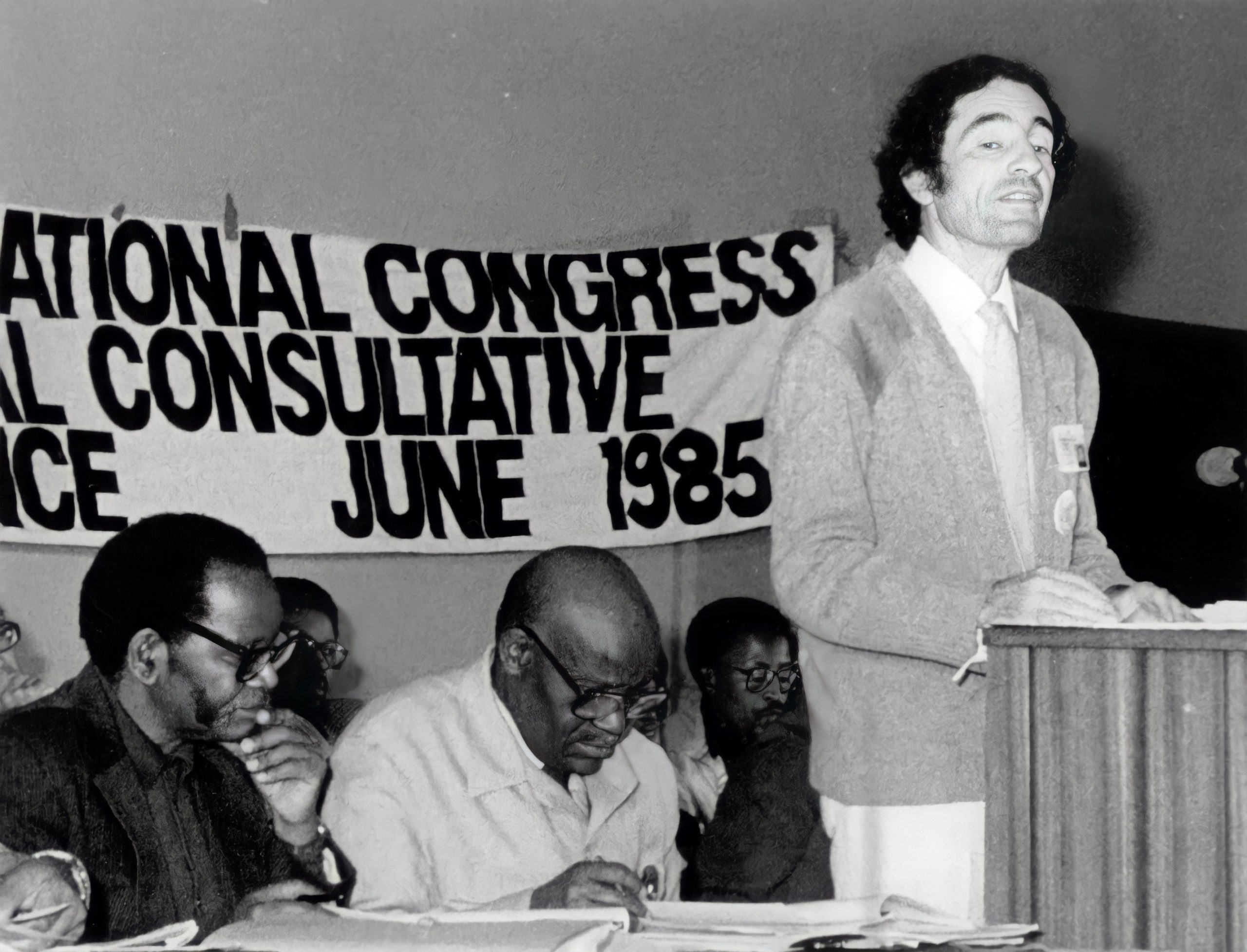

And a year or two later, in 1985, the ANC had a delegates conference, basically ANC people in exile — a few from underground in South Africa — in a small town called Kabwe in central Zambia. And we were surrounded by Zambian troops, in case commandos from the apartheid government regime came to take us all out and destroy us. We were discussing a future democracy in South Africa and fundamental rights for everybody. But in particular, we were discussing what to do with captives who’d been sent to destroy us and kill us, and should it be possible to use what were called — euphemistically called — intensive methods of interrogation. And one by one, I still remember so strongly the delegates coming. Some of them were in Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the ANC, young people, and saying, “No. We don’t use torture whatever the circumstances, whoever the enemy is, whatever the dangers, because we’re not like that. We are fighting for life. How can we be against life and disrespect the human personality even of those sent to kill us and destroy us?” I felt so proud. As a lawyer I felt, you know, we lawyers, we speak about rule of law and no torture, and it’s easy for us in our relatively comfortable lives. These were people risking danger every day in their work and their lives — from very, very poor backgrounds — insisting on those core elements that kept us together as an organization. We didn’t want to become like the others.

It wasn’t just a question of who was stronger physically, who could mess up and hurt the other side the most effectively to extract information. It was what we stood for, and the ANC, as an organization, took a very, very firm position that we put people on trial. We don’t have indefinite detention without a trial, whatever the suspicions might be, and we don’t use torture — sleep deprivation, water boarding, suffocating people, physical abuse. We just don’t use that, because that’s not the kind of people we are. And I mention this with some emphasis, because it meant, when eventually it came to writing the South African constitution, we didn’t need any persuading about the importance of fundamental rights. We had applied the theme of fundamental rights to our enemies in circumstances where conditions were often desperate for us. It was part of our integrity, and our personality, and that dream and sense of idealism that made us a liberation movement, and not just another group of people fighting for power, to dislodge one group and replace them with another group.

Of course the enemy came to me. I was never in the armed struggle. I supported philosophically the right of the oppressed people — who’d been denied the franchise, the vote, any possibilities even of protesting against the awful conditions in which the people lived — the right to use armed force as part and parcel of a broad political struggle, involving the whole world with the divestment campaigns, the isolation of racist South Africa, mobilization inside the country, bringing people together — black, white and brown — in a common endeavor to replace the system of apartheid with the system of democracy. But I’ve never been involved myself in using bombs and carrying a gun and anything of that kind. So I wasn’t personally involved in the armed struggle, but the armed struggle came to me in the form of state terrorism.

My friend Ruth First had been killed by a letter bomb in 1982. She was teaching at the Eduardo Mondlane University, a wonderful and marvelous intellectual. A seminar sponsored by the United Nations — and boom! She was blown up. And we cried so much, and we sang. We threw flowers into the grave. We carried her to the grave. And there was a portion of the cemetery in Maputo where many South Africans were buried, over 20 who’d been killed. And each time we went there we wondered, “That little space over there, is that for me?” Of course it was nearly for me.

I knew I was in danger. I actually bought an alarm for my car in the United States. I thought, “Well, I’ll use my life savings to protect myself,” and I spoke to Professor Jack Greenberg of Columbia University, and I felt in the U.S. you can buy anything. You can buy security with a little money that I’ve got. But he didn’t know about terrorism and protecting yourself. So he put me in touch with the human rights specialist from Precinct 34 or 49 or something in New York, and I went there, and it was Captain Smart, I think his name was — a very strange discussion. He was African American, and he knew that I was a South African in danger, and he assumed I was in danger because I was white — from the ANC, and I explained to him that the danger actually came from the white government not from the ANC. And in the end, what he said to me was, “You’ve just got to be paranoid. Change your modus of living. Don’t follow a regular pattern.” And I felt I was very secure in the apartment where I lived, but he said, “Have you thought about somebody drilling a hole in the ceiling?” And now I was really paranoid, because I thought at least I’m safe when I go to sleep at night. And I felt the car possibly was the most vulnerable thing, and eventually I ended up buying a very sophisticated alarm, which no one in Mozambique knew how to fit. Finally there was someone from Denmark, an electrician, and he fitted it, and it would make a terrible racket. It frightened me. I went away one year, and lent the car to a friend, and he felt he couldn’t give it back all dusty and dirty, and he hosed it down and short circuited the electrical machinery, and that was the end of any protection.

I felt that they wouldn’t go for me. I was clearly a law professor. I wasn’t working in the underground resistance. I was very friendly with many diplomats, including the United States. I would take visitors around, and I felt they wouldn’t go for me. I was so obviously a soft target and there would be a reaction against it. I was wrong.

A lot of people who were living in exile were vulnerable. Farmers in their fields, people in hospital. Everyone became a target.

Albie Sachs: It was the last throw of the securocrats in South Africa, saying, “You’re facing the total onslaught. We have to be ruthless in our response.” They assassinated an ANC person in Paris, her name was Dulcie September. A bomb exploded the Anti-Apartheid Office — the ANC office — in London, and clearly I wasn’t safe in Mozambique. But you didn’t want to give way. You didn’t want to flee because of the danger. So many people inside and outside the country were accepting risks.

I was doing fascinating, interesting work. I was working on a new bill of rights, why we needed a bill of rights in a free South Africa. And there was a lot of opposition from very progressive, very bright, young black students to a bill of rights. They saw it as a “bill of whites.” That the bill of rights was there to be opposed to democracy. “Once we get the vote, we won’t be able to do anything because our hands will be tied by provisions in the constitution that will insure that all the property…” and by law the whites owned 87 percent of the surface area of South Africa. But… “By law they would be able to hang on to 87 percent of the surface area through a bill of rights. They would constitutionalize apartheid.” And I had to explain — and under Oliver Tambo’s leadership I was given the authority and the responsibility of doing that — “The bill of rights can be emancipatory, a progressive bill of rights that includes social economic rights, that allows for transformation and change under conditions of equality and fairness is part of a bill of rights. We mustn’t allow extremely conservative, ultra-conservative people to write the bill of rights and tie our hands and make the constitution an unpopular document in our country. We must insure that the terms of the bill of rights recognize the rights of everybody, and especially the rights of the dispossessed, the marginalized, the poor, the women suffering under patriarchal domination, the children who have no rights at all, people dispossessed of their land, workers trying to get a decent job with a decent wage. They are all part and parcel of the bill of rights project, as well as people who invest who want their investments protected, who want to insure that there is a rule of law if there should be any economic transformation.” So we were debating all these questions while we were in exile, and it meant we were ready. We were ready when the day came.

In 1990 I was in Masaka (Zambia). We were working on some legal project with the Constitutional Committee of the ANC and we worked right through the lunch. I still remember, we just had some black tea and a stale roll to eat. We didn’t live it up in luxury in exile. The head of the Constitutional Committee said, “Well, let’s listen to the BBC.” It was about ten past three in the afternoon. We switched phones. We knew that Prime Minister-President de Klerk was going to make an announcement. We thought, “Not again. He has done so many times. Don’t have any expectations.” And this very confident English radio announcer’s voice said, “…and because of the unbanning of the ANC…” What? We jumped up! We danced around. There was a young chap who’d come clandestinely, to learn about doing secret underground work in the trade union movement. He was in the room and he was staggered. He’d only known illegality. We’d known legality years before. This was a restoration of negotiations which we’d wanted all our lives. He hadn’t known what it was like to be legal, and he couldn’t understand why we were so happy. Then it was a question of being able to go back.

Tell us what it was like when you finally saw Mandela and the other freed prisoners.

Albie Sachs: A few weeks later, in Lusaka, we were so excited. Nelson Mandela, after all these years, was coming to Lusaka. The ANC, that had been split — between those on Robben Island, those working in the underground in South Africa, and those of us in exile — was being united physically. We went to the airport, and an interesting and not very nice thing was happening. We were told some dignitaries could be on the tarmac, other important officials of the ANC behind the rope, and the rank and file would stay in the airport building itself. There were good security reasons for that, but somehow one felt this was a division that wasn’t very nice, and I wanted to be ultra-democratic, so I stayed in the airport. Then somebody pushed me forward and said, “No, Comrade Albie. You must go forward.” I went forward to the rope, and there we saw Mandela getting out of the airplane. Oh, what a special moment it was! And he came past, and we hugged, and it was terrific.

Later that day, there was a hall where we all met. I remember, as the people came in, we’d known them 30 years earlier. Thin, lively young people, lots of hair, dark hair. And now, gray hair, bald, sometimes with a paunch, but recognizable from the smiles, the voice. Coming in — about twenty of them coming in — and a couple hundred of us, and everybody running and hugging and embracing, and I felt very alone. I felt very alone. I wanted something emotional and special, and there wasn’t any particular person. The only time I felt the loss of my arm was that particular moment, that I’d be coming back to South Africa without my arm, and that was the moment I wanted an embrace. Eventually somebody came from the Eastern Cape, and he gave me a beautiful hug.

You say you felt the loss of your arm. What were you thinking of?

Albie Sachs: I thought back to that darkness when I’d been blown up, and I didn’t know what was happening, and total darkness. And I knew something terrible was happening, and I thought I was being kidnapped to be taken to prison in South Africa. And voices talking, and my body being pulled, and I shouted in English and in Portuguese, but not too loudly. I’m conscious even then that I’m a lawyer in a public place. We mustn’t make a noise. “Leave me, leave me. I’d rather die.” Then I’d faint and I feel terrible pain in the car. I thought at least they could have decent springs in the car if they’re gonna kidnap me. And then total darkness, total silence and a voice says, “Albie, this is Ivo Garrido. You’re in the Maputo Central Hospital. Your arm is in…” and he used the Portuguese word lamentável, “…it’s in lamentable condition. You have to face the future with courage.” And into the darkness I said, “What happened?” and a woman’s voice said, “It was a car bomb,” and I collapsed into darkness again, but with a sense of euphoria. I’d survived. For, I don’t know how many decades, every single day in the freedom struggle, wondering, “If they come for me today, if they come for me tonight, if they come for me tomorrow morning, will I be brave? Will I survive?” They’d come for me and I’d got through. I’d got through. I just felt fantastic. Then darkness, quiet, nothing.

I come awake. My eyes are covered. I can’t see anything but I’m feeling very, very light. I feel there’s a sheet on me and I tell myself a joke about Himie Cohen who, like me, is a Jew. He falls off a bus and he does this (gestures) and someone said, “Himie, I didn’t know you were Catholic!” “What do you mean Catholic? Spectacles, testicles, wallet and watch.” I told myself that joke. And I decided now to discover what had happened, what the woman meant about the car bomb. And I started with my testicles. Everything seemed to be in place. My wallet — my heart — was okay. Spectacles — I’m feeling any craters in my head. That’s all right. Then my arm slid down and discovered that my arm, my right arm, was short, and again, I felt marvelous. I’d survived, and it was only an arm, and I’ve got through. And I had a total extra conviction that as I got better my country would get better. Had nothing to do with rationality, evidence. It was just that powerful emotion that I’d got through the worst, and South Africa would get through the worst, and we were now on the way to constitutional democracy.

The recovery, it turned out to be a marvelous period in my life. I wouldn’t wish this on anybody, but it is great to be almost literally reborn and to have a fresh start. “Naked you come into the world.” I was almost naked. I was going to the beach. I almost went out of the world. Now I’m lying naked on this bed, and I’m coming back into the world, and I’m having to learn to do my bodily functions. Having to learn eventually to tie a shoe lace, to stand up, to walk, to run, to ride, to write with my left hand now. And each time I wanted to say, “Look, Mommy! Mommy, I can write! Look Mommy, I can tie a shoe lace.” It was actually a marvelous experience for me.

I think everybody wonders, “If I were to die tomorrow, would anybody cry?” And people thought I was dead, and they cried, and I knew that. I never have to ask that question again. It’s not a real question you ask, but it’s something that’s inside of you that you wonder about. And so much love came, and I developed a connection with England that I’d never had before. I’d lived there. I’d worked there. I’d written books. My children were born there, grew up there, but now it was the nurses taking off the bandages, cleaning my body, washing me with love and tenderness and… organized. It made me appreciate British people with an affection and a closeness far deeper than anything that I’d had before, and I emerged from that, I think, a warmer and more generous and a better person, and ready for the tasks at hand in South Africa.

Did you have a private moment with Mandela after that first meeting in Lusaka?

Albie Sachs: A week or two after the meeting in Lusaka I was in London, and Nelson and Winnie Mandela are coming to London and everybody’s excited. I’m excited all over again. Some people go downstairs and some upstairs, and it turned out that Madiba (Mandela’s nickname) was going to go to the one group and Winnie to the other group. We’re standing in a row, and she’s being escorted, Winnie Mandela, along the row, and comes to me, and she doesn’t recognize me. I hadn’t known her from before. And somebody says, “Albie Sachs.” “Albie Sachs!” she says. She opened her arms and she just embraced me, and that’s what I actually wanted from somebody, anybody. It came from Winnie. She’s a very controversial figure in South Africa. She was. But there are moments like that, that belong to you and another person, and even though I was often critical of some things she was associated with, I never forgot that particular moment. Then I could relax. That embrace that I wanted and needed had been given.

Now it became a question of planning for democracy, and flying back into South Africa after 24 years and about two months — and I knew it exactly then — so many days, and so many hours I’d been away. It was actually quite lovely. As the plane was flying in, it was from Zambia, there’d been a group of women from South Africa at a women’s conference in Zambia, and they all put out their hands, and clasped my one arm, and said, “Welcome home, Albie.” It was spontaneous. It was just a really lovely gesture. Then we go into the hall there, and I don’t have proper documentation. I’ve been stateless for a long time, but I’m coming back, and I’m not going to worry about documents. A white, Afrikaans-speaking official comes up to me, looking very stern, and he says, “Welcome home, Albie.” He was very gracious and very lovely. I see him occasionally at the airport. “Do you remember me?” he says. And I do remember that.

I was back, and flew down to Cape Town, and I’d had this dream I would climb Table Mountain. Every day I thought about climbing Table Mountain on my first day back, and I went to my mom, who’d been waiting all these years for me, and we had some tea. And I said, “Mommy, I’m going out to Table Mountain,” and I put on some appropriate shoes and we walked up the back. It wasn’t rock climbing. I didn’t know if I could do it. All the way right across the back and down. I even remembered some of the paths very, very well. And the other thing I was dying to do was to go to the symphony concert on Thursday nights. It had been a moment where, in the midst of all the imprisonment, and the pain, and the difficulties, if I could go to the concert on Thursday night, I could love my Beethoven and Mozart. And during the interval, someone came up to me and said again, “Welcome back, Albie. For 20 years you never missed a concert, except when you went to jail.” And I felt that, in a way, it was a reconnection.

Then the hard period of negotiations. Now Nelson Mandela is effectively the leader of the ANC. Oliver Tambo had a stroke and wasn’t able to do what he’d done before. Very close, working with Nelson Mandela in planning for a new constitution for South Africa. He didn’t play an active role in the details. His job was to really negotiate with President de Klerk, and represent the ANC publicly. But he played a very important role as the sort of person steering the tone, the temper, the quality, and insuring that there were good teams working on the constitution.

There were many of us working on the constitution. Many, many, many. Cyril Ramaphosa, a lawyer who’d been a trade union leader, became the head of the negotiating team, and we would work with him and with Nelson Mandela. We even had a quarrel with Nelson Mandela at one stage. I was sent by the ANC Constitutional Committee to fight with him. He wanted the votes to go to 16-year-olds, and we said, “No. Eighteen is the international standard.” He said, “No, but the youth fought hard for our freedom.” And we said, “But that was the youth of ’76, and now it’s 25 years later. They’re older people.” He said, “No, we’ve got to get the youth in.” He said there are seven countries that allow votes to even 14-year-olds. It was North Korea and Yemen, and we said, “We can’t be associated with countries that are not known for the open, pluralistic, democratic system.” Eventually he said, “Well, you will see. You will see that I was right.” But he accepted. He was wounded. Years later he gave that as an example. He was trying to drop a hint to President Thabo Mbeki about presidents must know when to admit that they’re wrong and to climb down, that they can make mistakes. So he acknowledged that he’d been wrong on that particular one.

We had a very industrious team. We worked day and night, day and night. We’d lived everywhere in the world. We’d lived in the United States and Canada. We’d lived in East Germany and West Germany. We’d lived in Cuba and we’d lived in the Argentine. We’d lived all over Europe, all over Africa. We didn’t have to study textbooks to know about political systems. We had to remember our lives in the Soviet Union. We’d seen advantages and disadvantages of different systems, and we had a very, very powerful negotiating team. And in the end, I think it’s fair to say all the main elements of our constitutional order derived their strength from the wisdom of the leadership of the ANC in wanting a constitution that would embrace everybody, and that was the vision of Oliver Tambo. He’d always had that. He’d always had the vision of the Freedom Charter, an open, pluralistic, democratic society where people could say their say. They could agree to disagree, as long as they agreed on certain basic fundamentals. No human being was more important than any other human being, that everybody had to be looked at with equal respect and concern. That was foundational, and that was our answer to the idea of the whites having special reserved seats and veto powers which would have been a disaster in South Africa. Whites had to be people like everybody else, with the same rights, responsibilities and duties. The same concerns, anxieties, hopes for their children, whatever it might be. Fully respected, but not somehow a specially protected group in our society. We fought hard for that, and we won that in the new constitution order.

Can you recall the first time you voted in a democratic South Africa?

Albie Sachs: I was in Cape Town. I stood in a line, thinking our whole lives had been devoted to the vote, because South Africa was an independent state. We didn’t want independence in that sense. We wanted “One person.” We used to say, “One man, one vote,” but we changed that to “One person, one vote.” It was our equivalent of a Declaration of Independence, and now we’d achieved it, and we stood in line, black and white, brown. Everybody — young, old. I didn’t feel anything. I was so surprised. I thought I would be elated, and somehow it was so banal, and just putting a little X. My vote is my secret but I can whisper to you — it was next to Nelson Mandela’s photograph — and I felt flat. I was surprised and disappointed. I wanted that sense of exultation, and somehow I suppose it made me equal in a way that I didn’t want.

I wanted to be a freedom fighter, doing something special for my life, for my country, and what this did was make me the equal in a marvelous — and in some ways a terrifying way, of the oppressors, of the rich, of the poor, people who’d done nothing. It was like a very ordinary act, and it’s not easy to become ordinary. Then I would start telling myself, the paradox of South Africa was we’d fought — all our passion — to create a boring society. A boring society in the sense that people didn’t kill each other and push each other around. We had all the normal complaints and dramas and hopes and disappointments of a democratic society.

You have to detox, and not everybody managed to do that. Living in dread, living in hope, living with your body on the line, living with physical pain, living in exile, living in imprisonment, confinement, all these years, and now you’ve just got to be an ordinary person in an ordinary society. And then another emotion started surging. It’s wonderful to be able to heal, to construct, to build, to enable things to grow. We’d spent all our lives dedicated to pulling something down, something evil and wicked. And I personally found that terrific.

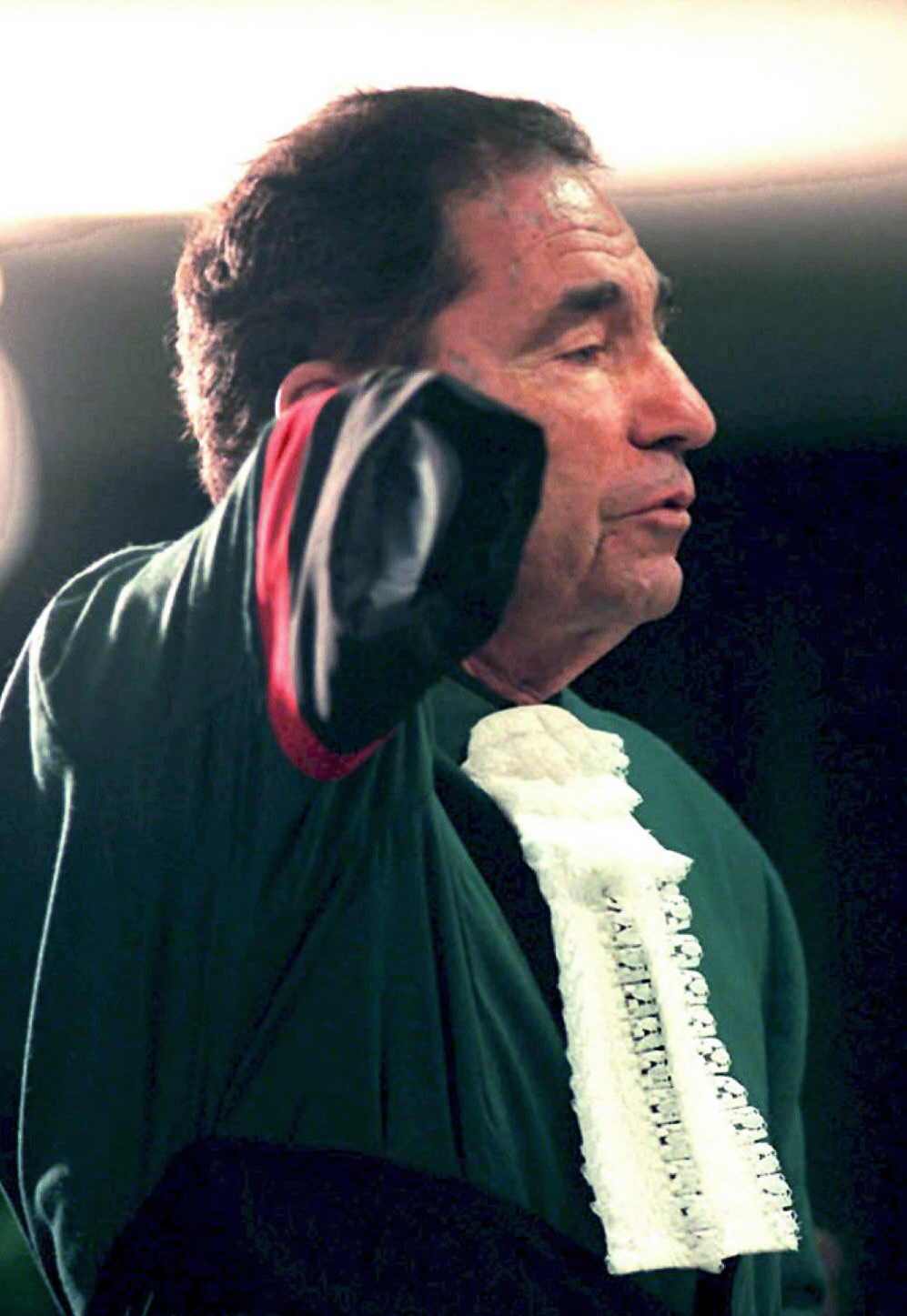

For me personally, as an individual, it was part of my physical recuperation to see the country now beginning to grow, and the constitution was the bedrock of everything. It didn’t build houses. It didn’t get people access to schools. It didn’t solve the problems of the country, but it gave a mechanism, a matrix, a way in which people could solve the problems without being at each other’s throats. So it was the foundation of everything. And then to be appointed to the court that defended that constitution in which our lives were invested, it was just a marvelous continuation of what we’d been struggling for. And now it’s 15 years. Whew! It just passed like seconds. I just remember being sworn in. We started our court with nothing.

We had one chair. I know we had one chair, because when the Chief Justice Arthur Chaskalson retired a few years ago, his secretary said how terrifying it was, sitting on the one chair that the court had, with this tall figure going around firing questions at her. And so from one chair we had to build up. It’s now an exceptionally beautiful building in the heart of the Old Fort Prison, where both Gandhi and Mandela had been locked up. It’s got a library that’s trying to be the biggest human rights library in the southern hemisphere. We get people from all over the world doing internships there. We have young South Africans working there, spending a year with us, recent law graduates. It’s a marvelous, open, friendly place, and I think our court has helped to pioneer legal thinking in a number of very, very difficult areas. We struck down capital punishment as being a violation of the fundamental dignity of every human being. The state just doesn’t kill in cold blood. Corporal punishment of juveniles, we’ve declared that was unconstitutional. We’ve developed a foundation for dealing with fundamental social and economic rights, that rights are not simply “keep out” in relation to the state, but obligations on the state to meet certain core ways of protecting human dignity when it’s really under threat. We have written on same-sex marriages. The court asked me to write the judgment, and we were unanimous that to deny people the right to celebrate their love, affection, intimacy, mutual responsibilities and supports — simply because they happen to love someone of the same sex — violated our equality clause. So it’s been not just a court trying to catch up with other courts in the world, but a court that’s been providing leadership in many, many areas.

Did you come to know Archbishop Desmond Tutu at the time of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission? When did you first meet Archbishop Tutu?

Albie Sachs: The first time I met him he wasn’t Archbishop. He was, I think, at Kings College, studying or teaching theology in London. This very bright little chap shared a platform with me, and we kind of eyed each other, and I was very, very serious and I think I spoke far too long. I was very worried about this, that and the other and I used the word “imperialism” quite a lot. I think it was him. I’m not even sure it was him. And then years passed, and suddenly he’s Archbishop Tutu, and he’s making wonderful speeches and he’s bringing civil society into the big debates, the grand dramas. He’s at the right place at the right time. He’s supporting the struggle for democracy with that very effective voice that he had, and of course he gets the Nobel Prize and we all feel we are getting the prize. Then, when it came to a truth commission, I was a strong supporter of the truth commission. Partly, we had to deal with crimes committed by ourselves, against people who we’d beaten up and tortured when they — before we introduced the Code of Conduct into the ANC. We had to come back to South Africa with clean hands, no secrets. We had to acknowledge this, explain why and what we did about it. But it was more important to deal with all the assassinations, the tortures inside South Africa, the violations. So I argued for a truth commission even before we got our new constitution.

By the time the Truth Commission was established, I was a judge so I couldn’t deal with that. In fact, we had to sit in judgment on whether the act — the statute that created the Truth Commission — could exonerate the torturers, the killers, from civil liability as well as criminal prosecution.

In a most exquisite judgment, filled with almost poetic legal language, written by the deputy head of our court, Ismail Mahomed, we explained why the project of getting truth — in exchange for not prosecuting the people who came forward to acknowledge what they had done — that project meant to encourage the truth to come out, we wouldn’t allow civil damages or imprisonment. And it had a very special meaning for me, because one day I got a phone call, and reception says, “There’s a man called Henri and he says he has an appointment to see you.” I said send him through. Henri had phoned me to say that he had organized the placing of the bomb in my car. He was going to the Truth Commission. Would I meet him? I was curious, and I was pleased that he had the courage, if you like, to come and see me. And opened the door and there’s a young person — tall, thin like myself. I’m looking at him. So this is the man who tried to kill me, and he’s looking at me. “So this is the man I tried to kill?” We don’t say that but it’s in our eyes. And we walk down, and he’s striding like a soldier, and I try to hold him up, to walk like a judge, to slow him down. We get to my office and we talk, talk, talk, talk, talk, talk, talk, talk, talk and eventually I stand up and I say, “Henri, I have to get on with my work now. I can’t shake your hand, but go to the Truth Commission. Maybe we’ll meet one day, and who knows?” I remember, when we walked back, he was just shuffling like a defeated person, going out the security door. It was over.

Months passed, and I’m at a party at the end of the year, and the band is playing. I’m very tired. We work very hard as judges. I hear a voice says, “Albie!” I looked around. “Albie!” My God, it’s Henri! And we get into a corner and I say, “What happened? What happened?” And he said, “I went to the Truth Commission, and I spoke to Bobby and Sue and Farouk.” He’s calling me Albie. He’s using their first name terms, people who were put into exile with me, who also could have been victims of the bomb. “I told them everything and you said that one day….” and I said, “Henri, only your face tells me that what you’re saying is the truth.” And I put out my hand and I shook his hand. He went away absolutely beaming, and I almost fainted. I heard afterwards that he suddenly broke away from that party. It was television people. He went home and he cried for two weeks. That moved me a lot. To me that was more important than sending him to jail. I wrote a book called The Soft Vengeance of a Freedom Fighter, saying that if we got democracy in South Africa, roses and lilies would grow out of my arm. Sending people to jail wouldn’t help me at all, but to get the country we’d been fighting for, that would be quite wonderful. That would be my soft vengeance. And now Henri and I — I don’t phone him up and say, “Let’s go to a movie.” But if I’m sitting in a bus and he sits down next to me, I say, “Oh Henri, how are you getting on?” We’re living in the same country because of the Truth Commission.

How would you describe the Archbishop’s role in the Truth Commission?

Albie Sachs: Archbishop Tutu had an absolutely fundamental role. He didn’t create it. He didn’t establish it. But he gave it a personality, a presence, a leadership. It couldn’t be somebody who said, “I’m neutral on torture.” You can’t be neutral on torture. He had emotion and feeling. He encouraged the people to sing hymns beforehand. African people would often feel — poor people — that they would get courage and strength from singing hymns. He encouraged witnesses to testify with a comforter next to them, to hold them, to hug them when they started crying and remembering the terrible things. He gave it an African feeling, a humane feeling, a quality of ubuntu, of coming out with the truth, acknowledging the interdependence of everybody. Perhaps it had more of a confessional aspect then I personally might have felt appropriate to my particular world view and outlook. But he was very much in touch with millions and millions of ordinary people. He said his section of the Truth Commission allowed the little people to speak.

They moved around. It wasn’t some big, important commission in a big, important building. They would go to little school halls. People would come and they would feel represented there. Since the Truth Commission has completed it’s work I’ve encountered Desmond Tutu quite often. Of course we’ve shared platforms. There’s a marvelous bond between us. There’s just something. It’s unstated so I’m not going to try and state what it is. He comes from a deeply religious background. I come from a totally secular background. When we went to an event at the Anglican Cathedral in Grahamstown, where people were asked to bless others by waving wands of plants, of branches, he asked me to bless him. In some ways it was quite cunning and tricking, because he’s involving me in a religious ceremony. But I did it with all my heart, because there is a bond and a connection — spiritual relationship — between us that’s very strong. He’s a marvelous voice for our country, and he’s funny and he’s provocative and projects himself in a way that really communicates with people.

What about former President Mandela? Have you seen him recently?

Albie Sachs: Nelson Mandela I’ve seen less of in recent years. As he said, he’s retired from his retirement. But his legacy, his memory, his personality is just so strongly with all of us, in so many ways. But he represented a generation, a culture, and many, many other people of that generation. I feel I must be one of the most privileged people on earth, because I was born into white privilege. It just came whether I wanted it or not. I could dream if I wanted to go to the moon. Having read Jules Verne, I could imagine I could do that. If I wanted to become a lawyer, I could imagine I could do that, or whatever it might be. But then I had the privilege of belonging to a freedom struggle. A wonderful, wonderful experience. You break through barriers, you work with others, you develop a sense of common humanity you could never do otherwise. Now, the privilege of working on the court that defends fundamental rights of the people, and the happiness that comes from having what I call L-L-L. Everybody knows www. L-L-L — “light, life, love,” and working in a beautiful court building that will be a legacy that will go on, with the marvelous art collection, and having a gorgeous little child, Oliver, born to Vanessa and myself. Lots of happiness at this period of my life.

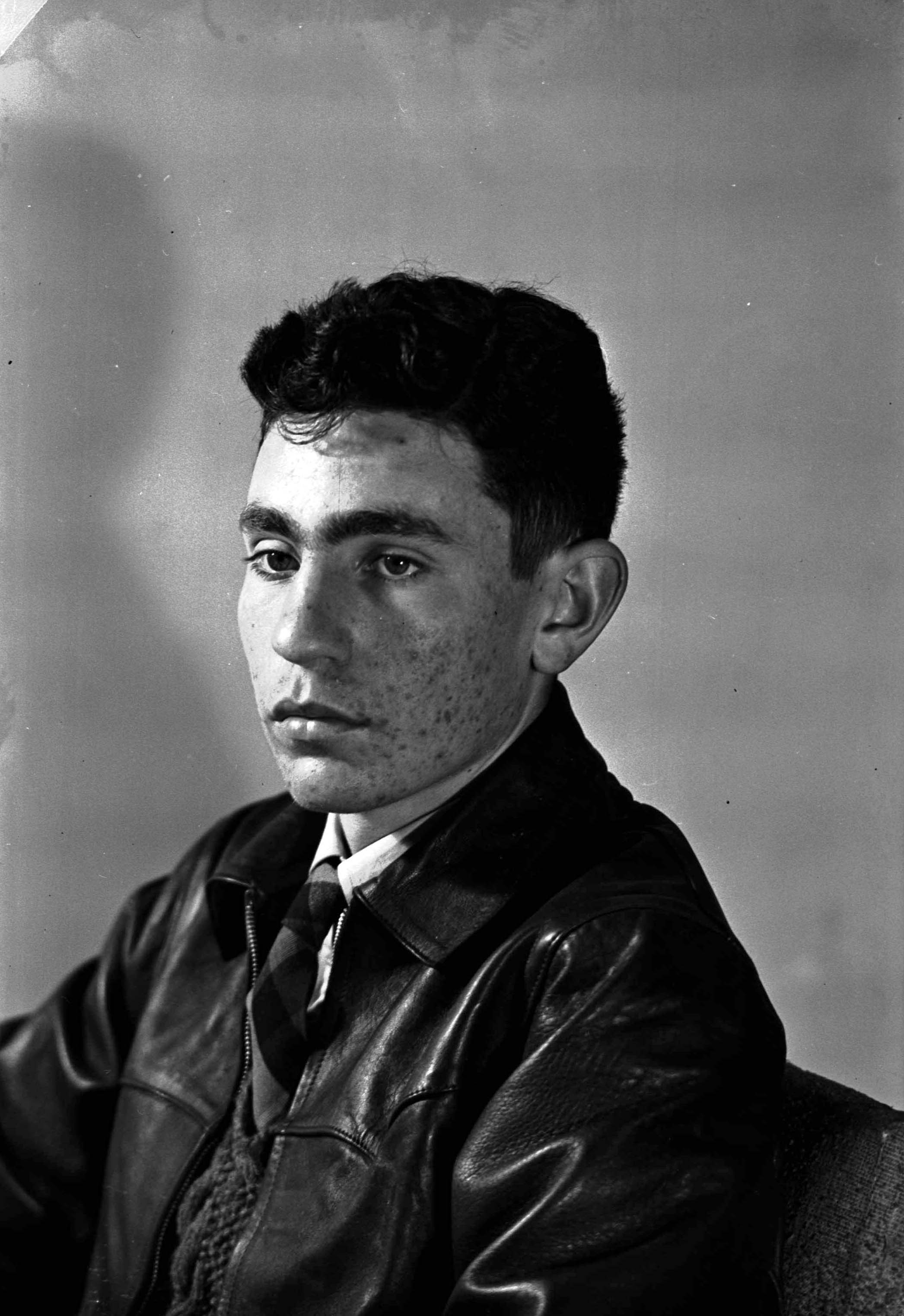

Speaking of children, we’d like to ask you about your own childhood. To start at the beginning, where were you born?