It’s a very sensual experience to eat. And I think romance is about the senses and a connection with somebody or with a group of people. It’s about that connection that is without words. Sometimes you just want to feel it.

Alice Waters was born in Chatham, New Jersey, the second of four sisters. Her father, Charles, worked as a management consultant while her mother, Margaret, worked at home. Her mother was interested in making healthy food choices for her family and limiting her children’s sugar intake, but by her own account, the young Alice was a picky eater, who took no great interest in where her food came from or how it was produced.

She enrolled in the University of California at Santa Barbara, then transferred to the University of California at Berkeley, arriving in 1964, just as the campus was rocked by the first of the era’s student-led protest movements. The Berkeley Free Speech Movement arose in response to the university’s ban on campus political activity by groups other than the two national political parties. Students who had participated in the Civil Rights Movement’s “Freedom Summer,” registering African American voters in the Deep South, fought efforts by the campus police to enforce the ban met with civil disobedience by Berkeley students, and mass arrests. Waters was inspired by the movement, particularly by the impassioned oratory of one of the movement’s leaders, graduate student Mario Savio. Berkeley students eventually won the right of free political expression on campus, allowing more students to question the political consensus of the Cold War era. The Berkeley campus and the surrounding San Francisco Bay Area became a center of resistance to what many saw as the oppressive conformity of the previous decade.

Waters was studying French history and culture with particular emphasis on the tumultuous century encompassing the French Revolution and its aftermath. As part of her program, she had the opportunity to study for a year in France, and at age 19, she packed her bags for Paris. In France, Waters found that her fascination with things French extended beyond history to the food culture and cuisine of contemporary France. She lived at the bottom of a market street where she was enchanted by the fresh seasonal produce for sale and the custom of buying fresh ingredients daily.

In the United States, the growth of suburban communities and interstate highways had separated most people from the source of the food they ate. In the 1950s and ‘60s, more and more Americans shopped at supermarkets or grabbed food on the run from fast food establishments. The nation’s diet was increasingly dominated by processed foods, transported over great distances and preserved by freezing and canning, or with chemical additives. In France, Waters found, more people shopped at farmers’ markets, buying produce in season from the farmers themselves, with close attention to the source and quality of everything they ate. While Americans bought their bread and baked goods sealed in plastic, the French more often bought theirs fresh from the oven of a neighborhood bakery. In later years, Waters recalled her experience in France as a great awakening of the senses and an expanded consciousness of the value of dining as a communal experience.

After a year, she returned to Berkeley and found the campus and surrounding community more convulsed than ever by resistance to America’s military involvement in Vietnam. Waters volunteered for the congressional campaign of antiwar journalist Robert Scheer, and surrounded herself with a circle of like-minded friends, preparing communal meals for political meetings that lasted long into the night.

After graduating from Berkeley in 1967 with a degree in French cultural studies, she trained at the International Montessori School in London, intrigued by the Montessori method of childhood education, which emphasizes hands-on experience of practical activities. She traveled to Turkey, experiencing another food culture and an ancient tradition of hospitality, and then spent another year in France, deepening her knowledge of French gastronomy.

Back in Berkeley, she taught in a Montessori school and continued cooking for friends, experimenting with local produce and the cooking techniques she had absorbed in France. More and more of her time and interest centered on food and the cultivation of a mindful practice of eating and entertaining. She began writing restaurant reviews for a local “underground” weekly, The San Francisco Express Times, and her column soon became a forum for her thoughts on tasteful, healthy eating. By this time, she had concluded that whatever contribution she would make to society would not be in the form of traditional political activism.

As friends from the antiwar movement extended their activism into environmentalism and other causes, Waters increasingly came to see the communal table as the centerpiece of a healthy society. In 1971, at age 27, Waters opened a restaurant with a small group of friends. With only $10,000 in capital, they rented a two-story stucco house on Shattuck Avenue in Berkeley.

Waters named it Chez Panisse for a character in the memorable trilogy of films by French playwright and director Marcel Pagnol. She sought to recreate the experience of dining at a French country inn. Using only the freshest seasonal ingredients, Chez Panisse offered a single fixed-price, four-course dinner menu that changed every evening.

The restaurant opened to a packed house for two consecutive servings on its first evening, but Waters found it difficult to control costs. Her father mortgaged his house to help keep the business afloat and volunteered management advice to rationalize the restaurant’s operations. Eight years passed before the business showed a profit, but Waters maintained her insistence on the highest quality of seasonal, locally sourced ingredients, and Chez Panisse gradually won a devoted following. Waters formed close working relationship with her suppliers, building a network of farmers, ranchers and artisans. She gave menu credit to the farms that provided her ingredients, a practice that other restaurateurs soon emulated.

In 1980, Waters expanded the operation to include an upstairs café serving an à la carte menu for lunch and dinner. Waters married San Francisco wine merchant Stephen Singer; their daughter, Fanny, named for another character in the Pagnol films, was born in 1983. The following year, Waters opened Café Fanny, a breakfast and lunch establishment a few blocks from Chez Panisse.

Initially, Waters had sought fresh ingredients for taste alone, but in her dealing with farmers, she found that organic produce offered the best flavors, and in time, she became an enthusiastic advocate of organic farming and environmentally sustainable agriculture. Organic farmer Bob Cannard of Green String Farms in Petaluma, California joined her network of suppliers in 1985. Cannard’s principles of caring for the soil that produces the food we eat have guided Alice Waters ever since.

In 1992, Alice Waters became the first woman to receive the James Beard Award as the Best Chef in America. As visitors from around the world flocked to the little restaurant in Berkeley, Alice Waters became a national figure. The phrase “California Cuisine” entered the language, and restaurants around the world proclaimed their dedication to “farm-to-table” dining. Waters continues to insist on serving locally sourced foods, and devotees of her philosophy have become known as “locavores.” The Chez Panisse supply network now encompasses 85 farms and ranches, all within 100 miles of the restaurant.

Alice Waters has worked to promote her ideas in the world beyond Berkeley’s so-called “gourmet ghetto.” A letter to President Bill Clinton persuaded him and First Lady Hillary Clinton to create an organic vegetable garden at the White House. Waters has shared her ideas — and her recipes — in a series of bestselling books, beginning with The Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook in 1995.

That same year, Waters founded the Edible Schoolyard Project at Martin Luther King, Jr. Middle School in Berkeley. Waters had begun working with the Berkeley public school system to integrate growing, cooking, and serving food into the school curriculum. Informed by her earlier training in Montessori teaching, the Edible Schoolyard Project allows the students to tend a one-acre organic garden and has turned an abandoned cafeteria into a “kitchen classroom, ” where the students learn to prepare the food they have grown themselves. On the 25th anniversary of her restaurant, Waters created the Chez Panisse Foundation to support educational outreach. There are now Edible Garden programs in Greensboro, North Carolina and in New Orleans, as well as in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

In 2001, Gourmet magazine named Chez Panisse the Best Restaurant in America. The PBS television series American Masters profiled Waters in its 2003 film Alice Waters and her Delicious Revolution. As the world has learned to enjoy and imitate the style of cooking Alice Waters pioneered, she has received numerous honors for revolutionizing the way we eat and the way we think about food. In 2004, she received the Lifetime Achievement Award of the James Beard Foundation, while the National Audubon Society honored her with the Rachel Carson Award for her commitment to sustainable agriculture.

In 2002, Waters became vice president of Slow Food International, an organization that works to preserve biodiversity and local food traditions. She conceived and helped create the Yale Sustainable Food Project in 2003, and in 2007, the Rome Sustainable Food Project at the American Academy in Rome. She was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2007 and shared the Harvard Medical School’s Global Environmental Citizen Award with Kofi Annan in 2008.

In a 2009 appearance on the 60 Minutes television program, she made an open appeal to the newly elected president, Barack Obama, to set the example of cultivating an organic vegetable garden. The First Lady, Michelle Obama, took her up on the suggestion and made the White House vegetable garden a centerpiece of her campaign against childhood obesity.

The Edible Garden Project has expanded into an international movement, teaching schoolchildren to grow and prepare natural healthy foods. Alice Waters has created the School Lunch Initiative, a national program aiming to make healthy, fresh, and sustainable meals a part of every school day. She collaborates with the UC Berkeley Center for Weight and Health and the Center for Ecoliteracy, to advocate for free school lunch programs and to develop a sustainable food curriculum in every public school. She hopes to see history and the sciences taught through the cultivation and preparation of food. She is now campaigning for the Department of Agriculture to include organic fruits and vegetables in the nation’s school lunch program.

Alice Waters has been honored not only by her own country but by the nation whose culture inspired her life’s work. In 2010, she was inducted into France’s Legion of Honor. On the 40th anniversary of Chez Panisse in 2011, Alice Waters was honored with the inclusion of her likeness at the Smithsonian Institute’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington. In 2015, she was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Obama, recognizing her achievement in raising Americans’ awareness of healthy, sustainable eating and sustainable agriculture as the keys to a healthier population, a more livable environment, and a happier society.

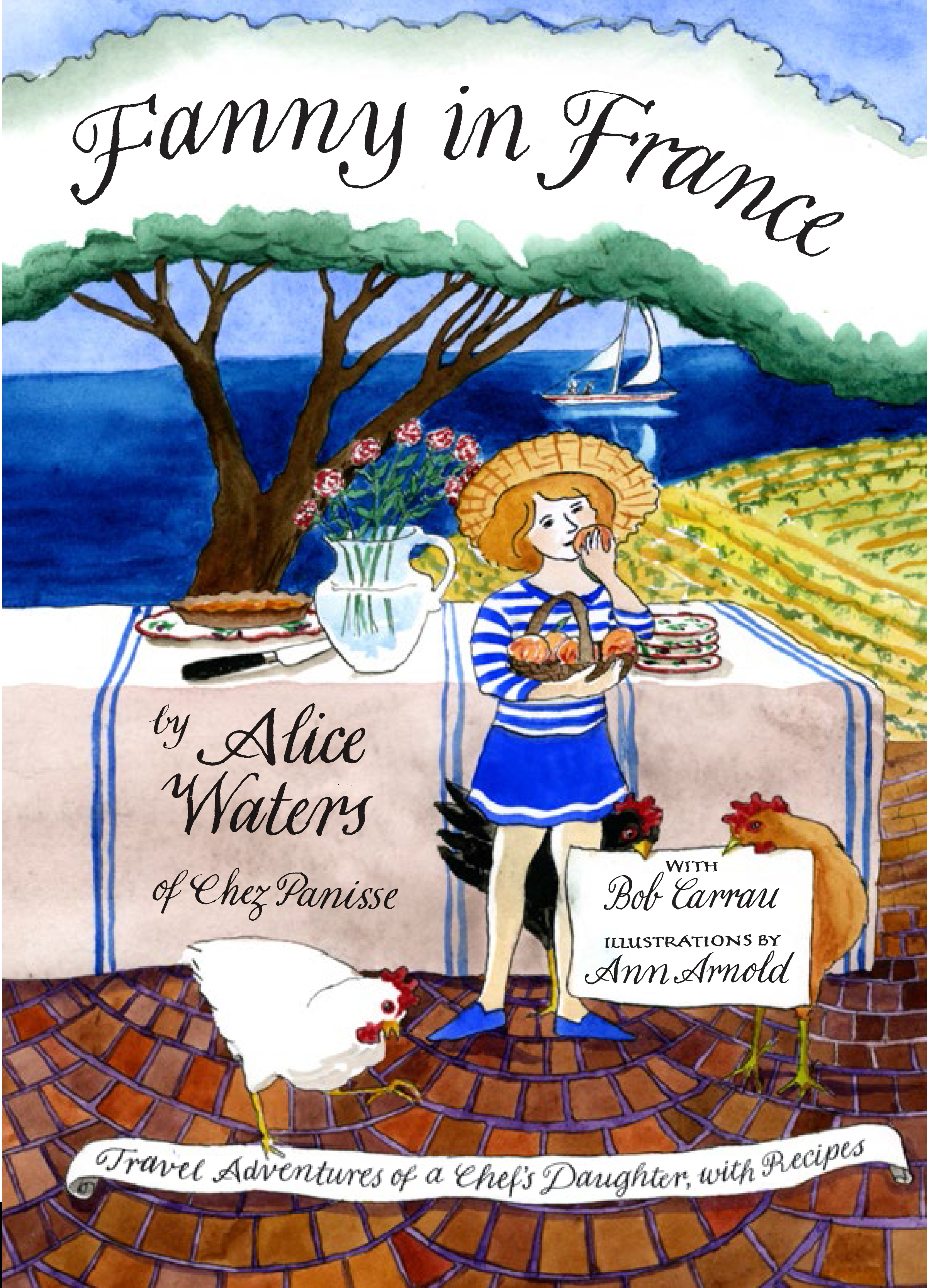

Waters has now published more than a dozen books, including The Art of Simple Food (2007), The Edible Schoolyard: A Universal Idea (2008), In the Green Kitchen (2010), 40 Years of Chez Panisse: The Power of Gathering (2011), My Pantry (2015), and Fanny in France: Travel Adventures of a Chef’s Daughter, With Recipes (2016). The latest is her critically acclaimed memoir, Coming to My Senses: The Making of a Counterculture Cook (2017).

Although Waters has employed a series of talented chefs to run the kitchen at Chez Panisse, she continues to eat in the restaurant almost every day, while supervising the overall operation from her modest 1908 Craftsman-style home a few blocks away.

Owner of Chez Panisse, “the nation’s most widely-acclaimed restaurant,” Alice Waters has transformed modern cooking. She first became inspired by great food and the culture surrounding it on a trip to France at age 19. After earning a degree in French cultural studies at the University of California, she traveled throughout France, then returned to Berkeley, California.

At first, Waters intended to be a teacher, but she soon found she preferred cooking to teaching, and decided to open a neighborhood bistro like those she had loved in the South of France. It was eight years before Chez Panisse showed a profit, but in time, food lovers sought it out, and restaurant chefs in other cities began to imitate her approach.

Her interest in serving the finest produce in season taught her that foods grown organically, in environmentally sound conditions, would produce the best flavors. Today, Alice Waters encourages American families to eat together, and to take an interest in what they eat, and how it is grown and prepared.

You went to Paris when you were 19. When you started eating over there, what was the influence that had on you?

Alice Waters: The food was really a very big surprise because I just was afraid of things that I didn’t know about. And yet, in the context of a country that really cared so much about how people ate and what people ate, I was drawn into it. You know, like the aroma of the bakery. You go in and you taste that warm baguette. And then you go in the next day, and you want that same baguette. It was a seduction, in a way. It was like, just seeing a beautiful place setting, seeing all of the fruits, the vegetables, that were going to be on the menu displayed in the front of the restaurants to bring you into that experience. And I was just drawn in.

I was going to school, and every day, I walked from my little apartment up the market street to get to the university. And I couldn’t believe the beauty of the vegetables — the lettuces, the colors. And it was always changing because it changed with the seasons. It even changed from a morning market to an afternoon market because the farmers would bring in different things in the evening. And I guess the aliveness of the food was irresistible.

You’ve said the strawberries you ate in France reminded you of something you had known long before.

Alice Waters: Well certainly, those wild strawberries that I had in France had a kind of intensity about them. I do remember eating strawberries right in the garden when I was a little child, when they were warm in the sun. And I picked them off the plant. And so, that stayed with me somehow. And then, when I tasted that wild strawberry, I wanted to know exactly where it came from. And then I found out that you had to go out in the woods to pick them. And I wanted to have those again here in California. And actually, I found somebody who was willing to plant the forests at Chez Panisse.

Lots of people have gone to Europe and noticed that there was better food, more intense food, as you say. What was different about you that caused you to bring that experience home and make it a life’s work?

Alice Waters: It’s hard to say exactly what it was because it was a big picture of the culture of France. It wasn’t just about the food. It was about the concerts we went to. It was about the beauty of the parks, of the cathedrals, of the cafés — the life that the people were living. It seemed so civilized to me; it seemed so real, somehow. And I just wanted to live like the French. And when I came back home, I tried to find the food, of course. But I lit the candles on my table when I sat down for dinner. I set the table in a very particular way. I bought the napkins, and I folded them. I even picked flowers in the neighborhood to put on the table because I wanted it to be beautiful.

And food, good food, was the center of conversation and connection to the community.

Alice Waters: Exactly. I didn’t make that connection to the community at the beginning. Even at the beginning of the restaurant, I was looking for taste. I was really looking for taste. And ultimately, I ended up at the doorsteps of the organic local farmers because they were the ones that were growing food for taste, and they had different varietals that they planted. And when they brought them to the restaurant, or they brought them to the farmer’s market, they were just picked. So they had that aliveness about it — the food.

When you returned from Paris, you were back in Berkeley. It was the ‘60s. It was ground zero for the anti-war movement, the Free Speech Movement. How did the politics of the time influence you?

Alice Waters: I know I became politicized. I was so on the fringes of that movement — the Free Speech Movement. But I listened very carefully to what Mario Savio was talking about. I found out later, of course, he was Sicilian and always had a bottle of wine with his meals. And he had, I’m sure, this big vision of how we could change the world into a place that we all came together — that we felt responsible for each other, in a way. And I really believed him.

Even before you opened Chez Panisse, you were having small dinners with very interesting people in Berkeley. Can you tell us about the time right before you opened your restaurant?

Alice Waters: A friend of mine, David Goines, was a good friend of a number of people that were printing a small newspaper in San Francisco. It was called the San Francisco Express Times. And so, they would have meetings at our house, and I would be there, sort of listening to their conversations about what they wanted to put in the newspaper. And then David had this idea: “Why don’t we do a restaurant column?” — and called it “Alice’s Restaurant.” So I would try and find a recipe to be in that part of that column. And it pushed me into asking everybody I knew, “What do you like to eat?” and “Do you have a special recipe that I could use for this column?” I started making these dishes at home and then feeding them to the people that had gathered to work on the newspaper, and they loved what I cooked. So it was kind of a way for me to research about food. At the same time, I was sort of cooking because I was researching for the column and trying out the recipes of friends.

Was there a point when you realized that you had a special gift for cooking?

Alice Waters: I wasn’t sure that I had a gift for cooking, but I knew that I had a gift for finding the ingredients, finding the dishes the people liked to eat, and that I was still intimidated by the cooking process. So that’s why I relied on recipes from other people. I wasn’t at all ready to improvise. Luckily, someone gave me the cookbooks of Elizabeth David. And her recipes were very bare bones. So I had to interpret what she meant, and sometimes I was less successful, and sometimes I was more. But she gave me a real aesthetic about food — the simplicity of it, the kind of purity of it she instills through her beautiful writing.

So if it’s not a quarter cup of this and a pinch that, what’s the essence of a good meal?

Alice Waters: I think it all has to do with ingredients. It’s about ripeness. It’s about finding the right olive oil and tasting and comparing. Which one do I like better? What vinegar do I want to use? How much garlic? But you’re always tasting and adjusting, all the way to the end. But I cook very, very simply.

You’ve said that you’re a good cook but a great taster. Do you have a heightened sense of taste?

Alice Waters: I think I might have a heightened sense of taste, but it comes a lot from practicing. It’s always interesting to me, that dialogue with myself, with other colleagues. Does it need more of that? Should we add that to it? And when you come out with something that’s better than the sum of the parts, it’s exhilarating.

Do you like to cook with others or alone?

Alice Waters: I love to cook with other people. I do. I usually have friends come for dinner on Sundays. I buy the ingredients, and then they all come, and we talk about what we want to do. It’s really fun to be getting the opinions of other people. And it’s the way that we cook at Chez Panisse. We don’t have recipes that we follow. Yes, we do in pastry, when we know certain quantities, because you need that. But we’re using our oral history of cooking in the kitchens. We’re being inspired by cookbooks, but we’re really fine-tuning it together. And every day, it’s a new day.

Let’s talk about 1971. You didn’t have that much money. You were only 27 and you wanted to open a restaurant. How did you pick this place on Shattuck Avenue?

Alice Waters: I was looking at a lot of different places in Berkeley with my friend — my good friend Tom Letty — who was so excited about the idea of my opening a restaurant. He thought it was the greatest idea because he had eaten my food, and we had been such good friends, and he knew that this was my passion. So we went to places that were sort of a little too dark or too big. And then we saw this house on Shattuck Avenue that was a plumbing shop. It was just a two-story stucco house, but it was commercially sound. And I said, “Ah! It could be in a house.” So it could be just like I was serving my friends at home.

Why didn’t you just call it Alice’s Restaurant, like your newspaper column?

Alice Waters: Well, “Alice’s Restaurant,” that song, was attached to an Alice on the East Coast. And I knew I didn’t want my name involved. I had gone to see movies with Tom Letty, who was running a repertory theater, and I saw the films of Marcel Pagnol, and I fell in love with these films made in the ‘30s in France. And one of the characters in the films, his name was Panisse. And it had a certain ring to it. It could have been Chez Marius or Chez Fanny. But the name Panisse stuck. And as Tom pointed out, he was the only one in the films that ever made any money.

We’re in your kitchen with this gorgeous fireplace. When you lit it, you put some rosemary on the log. Do you always do that?

Alice Waters: I always like the perfume of the fire in the house and rosemary. It quickly changes the tone of the room. It changes the way that I feel. So whenever I come home from a trip, I just put some rosemary, light it on fire, and just walk around the house. I used to do that at Chez Panisse, and sometimes we need to do that to make the entryway really inviting, if we’re cooking a dinner from the South of France or having a party. And aroma is very, very effective. Bread cooking or pizza cooking up in the wood oven upstairs really helps people to feel at home.

It’s not just the taste or even the look?

Alice Waters: It’s not just the taste. No. I want to really excite all of people’s senses. So I want it to smell good. I want it to taste good. I want it to look really beautiful. I don’t want too-loud sounds — the music to be too interruptive. I want maybe a little bit of music, when it’s quiet at the beginning of the evening, or a little jazz late at night. But I don’t want it to be interrupting people’s conversations.

But I like people to pick things up with their hands, too. So we always serve something — whether it’s a little candy at the end, or whether it’s a crouton to begin, and they pick that up. That you want them to peel the orange or — again, I always thought that sometimes we should have a little sign that says, ”Eat with your hands,” so that you feel comfortable about picking up the quail and eating the bone — the leg.

I was struck in the master class that you teach online. You said at one point, “Peel the lemon toward you,” because it’s more beautiful.

Alice Waters: Well, I think also more aromatic, again.

Is there a connection between food and romance?

Alice Waters: For me, absolutely. Absolutely. It’s a very sensual experience to eat. And I think romance is about the senses and connection with somebody, or with a group of people. It’s about making that connection that is without words. Sometimes you just want to feel it.

Your parents helped you when you started the restaurant. What did they think of your success?

Alice Waters: They were so proud of me. It’s so great when your parents really support you, but that you are so grateful to them for doing so. My parents have always had a garden, and my father had a feeling he could help me with the restaurant. I resisted it at first. But he came in, and he was so patient. He worked with our staff. He just introduced all of his organic, if you will, management skills. And he said — one of the things he said is, “You have to say, Alice — you can’t order people to do things. You have to say ‘please’ and ‘thank you.’ And you have to tell them what they do well first, before you tell them what they don’t do so well — and how they can improve.” And I have really tried to practice what he proposed.

I have never really managed the restaurant. We had a little group of us, and we divided up the management between the dining room manager, the café manager, the bar manager, the main cook in the kitchen, the main pastry person, and we all had our jobs. It was somebody also in the office. My father set up that group, too. He called it the ops group.

You could have expanded. It’s almost 50 years since you opened. You could have easily expanded the place and filled it every night and made a lot of money. How come you didn’t? It’s still a small restaurant in a house.

Alice Waters: I really believed in the values that I learned in the ‘60s. And one of them was not to do something to make money. Don’t do it to make money. Do it because you love the work. And I was never, ever interested in making money. I was ashamed even that I put the money from the restaurant in a bank. But I knew that if I made really tasty food, that people would come to eat, and that I would be able to keep the restaurant open. And fortunately, it has made money. But it’s important to me to pay the people well who work there. It was never about having an empire with lots of different restaurants. I didn’t want to travel to another place.

I just couldn’t imagine doing it. I couldn’t imagine doing it well. I felt like there would be a compromise always because it takes so much to keep Chez Panisse just at a certain level of quality. I just couldn’t imagine doing it. And again, I never wanted to sort of get on a plane and go visit these other places. I love knowing the customers who come in. I know them by name. I love knowing all the people who work there. There are almost 110 people who work at Chez Panisse.

You must have been asked so many times to open a restaurant in Los Angeles or New York. You were even asked to open one at the Louvre in Pair.

Alice Waters: Well, that was the one place where I really entertained the idea because it was to be part of the decorative arts wing of the museum. I thought it could be sort of an international symbol of the beauty of food and of nourishment. And what better place than the center of Paris? I never imagined that I would run that place myself, but I imagined that it could be a place maybe run by a whole number of chefs from around the world who would bring his or her cooking to that location.

It was fairly shocking at the time that an American woman was asked to open a restaurant in France. What happened?

Alice Waters: Well, I understood that it was a very big bureaucracy. And that when, in fact, all of the different people who made decisions about that particular location — that I wouldn’t be able to do it the way that I wanted to do it. I was given a contract basically for a kind of fast food restaurant. And I said no.

At a time when so many people are talking about income inequality in the United States and the difference between the owners or the CEOs and the workers, you gave the workers in your restaurant stock options.

Alice Waters: Yes, we did.

That was fairly revolutionary.

Alice Waters: I guess, again, that when you have the pleasure of working with a group of people — when you’re not in that pyramid structure of a normal restaurant kitchen, where there is a chef at the top and there’s sort of the commis, the workers, at the bottom — when you’re working more as a team, that it seems right to have some benefit from the success of the restaurant. I’ve even thought maybe it just should be like the Cheese Board across the street, a cooperative.

You recently had a yard sale at the restaurant. Whose idea was that?

Alice Waters: Well, Fanny and I had always had yard sales out in front of the house, and I believe that there are beautiful things to be had at the flea market. I’ve always gone to the flea markets around the world, particularly in France, and brought things home. At the beginning of Chez Panisse, we used to go to the flea market to buy mismatched silverware that we had in the dining room. We had glasses. We had dishes that we bought. But especially, things like a cast iron pan. All of my cast irons have been purchased from the flea market. And they’re inexpensive. They’re so well made, you know. Whether it’s a belt or whether it’s a dress — I mean to last for 40 years, something that is made well, it’s a gift to me. I love finding them in the flea market. I wish that I could not buy one new thing ever again. I love to go to those second-hand stores.

There was something about the fact that I was sitting there, and that there were all these menus from the years before, and that there were clothes — my hats, my dresses — that I wore at the beginning of Chez Panisse. There was something about them being practically given away in a yard sale that touched people. And of course, I just felt the emotion of that.

Do you feel different now than you did in the ‘60s? Francis Ford Coppola, Bill Clinton, movie stars, everybody comes to your restaurant. You teared up when you were talking about the yard sale.

Alice Waters: That’s the kind of feeling that we all had in the ‘60s. It was like, you’d take your bike down to the freeway; you’d park it. You never locked it up. You put your thumb out; you’d get picked up, driven to San Francisco. Same way back home. Pick up your bike. Ride up the hill. I just felt a sense of generosity. And we weren’t afraid. We weren’t thinking about: “What is that person going to give to me?” It was always just a feeling of “You can share this. You need a room? Come stay in my room.” And it was the way I felt when I traveled around the world, that those indigenous cultures have that sense of hospitality. I went to Turkey, if you can imagine, and pitched a tent. Two women pitching a tent out in a field. And the next morning finding a bowl of warm goat’s milk under the tent flap. You know? Where is that sense of humanity now?

It’s in there. I really feel like it’s in there. It’s just been buried by greed. And we have to find our way out. I really feel like public education, it’s our last truly democratic institution, as Gloria Steinem said many years ago, and I believe that. We can reach every single child. Well, here she is, open and learning. And we can. We can be the change we want to make. We can teach these values. We can teach them how to take care of the plants. Look at the soil. See all the earthworms and the little bugs in there and how important they all are to the big picture. And it’s utterly fascinating to children. Utterly fascinating.