I think that’s why I’m a storyteller. I take all these disparate events and connect them. I have to make them seem inevitable and yet surprising and plausible. That’s what I think life is like too. I have the luxury to do exactly what it is we all need time to do... think about the mystery of life.

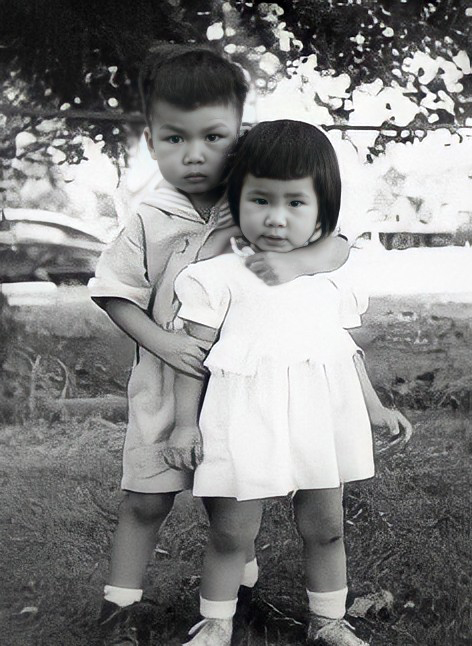

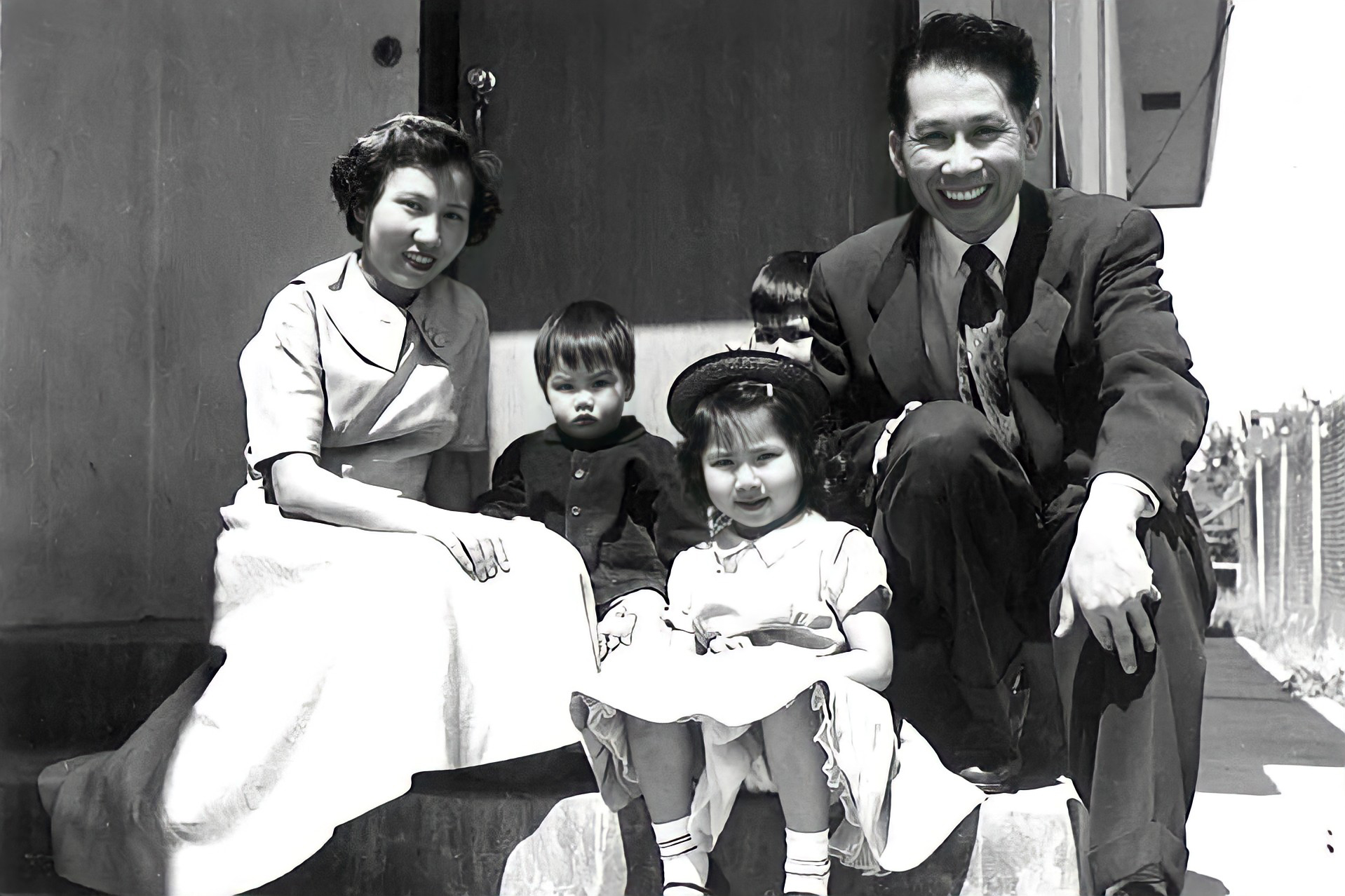

Amy Tan was born in Oakland, California. Her family lived in several communities in Northern California before settling in Santa Clara. Both of her parents were Chinese immigrants. Her father, John Tan, was an electrical engineer and Baptist minister who came to America to escape the turmoil of the Chinese Civil War. The harrowing early life of her mother, Daisy, inspired Amy Tan’s novel The Kitchen God’s Wife. In China, Daisy had divorced an abusive husband but lost custody of her three daughters. She was forced to leave them behind when she escaped on the last boat to leave Shanghai before the Communist takeover in 1949. Her marriage to John Tan produced three children, Amy and her two brothers. Tragedy struck the Tan family when Amy’s father and oldest brother both died of brain tumors within a year of each other. Mrs. Tan moved her surviving children to Switzerland, where Amy finished high school, but by this time mother and daughter were in constant conflict.

Mother and daughter did not speak for six months after Amy Tan left the Baptist college her mother had selected for her, to follow her boyfriend to San Jose City College.

Tan further defied her mother by abandoning the pre-med course her mother had urged, to pursue the study of English and linguistics. She received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in these fields at San Jose State University. In 1974, she and her boyfriend, Louis DeMattei, were married. They were later to settle in San Francisco.

DeMattei, an attorney, took up the practice of tax law, while Tan studied for a doctorate in linguistics, first at the University of California at Santa Cruz, later at Berkeley. By this time, she had developed an interest in the problems of the developmentally disabled. She left the doctoral program in 1976 and took a job as a language development consultant to the Alameda County Association for Retarded Citizens, and later directed a training project for developmentally disabled children.

With a partner, she started a business writing firm, providing speeches for the salesmen and executives of large corporations. After a dispute with her partner, who believed she should give up writing to concentrate on the management side of the business, she became a full-time freelance writer. Among her business works, written under non-Chinese-sounding pseudonyms, were a 26-chapter booklet called “Telecommunications and You,” produced for IBM.

Amy Tan prospered as a business writer. After a few years in business for herself, she had saved enough money to buy a house for her mother. She and her husband lived well on their double income, but the harder Tan worked at her business, the more dissatisfied she became. The work had become a compulsive habit, and she sought relief in creative efforts. She studied jazz piano, hoping to channel the musical training forced on her by her parents in childhood into a more personal expression. She also began to write fiction.

Her first story, “Endgame,” won her admission to the Squaw Valley writer’s workshop taught by novelist Oakley Hall. The story appeared in FM literary magazine, and was reprinted in Seventeen. A literary agent, Sandra Dijkstra, was impressed enough with Tan’s second story, “Waiting Between the Trees,” to take her on as a client. Dijkstra encouraged Tan to complete an entire volume of stories.

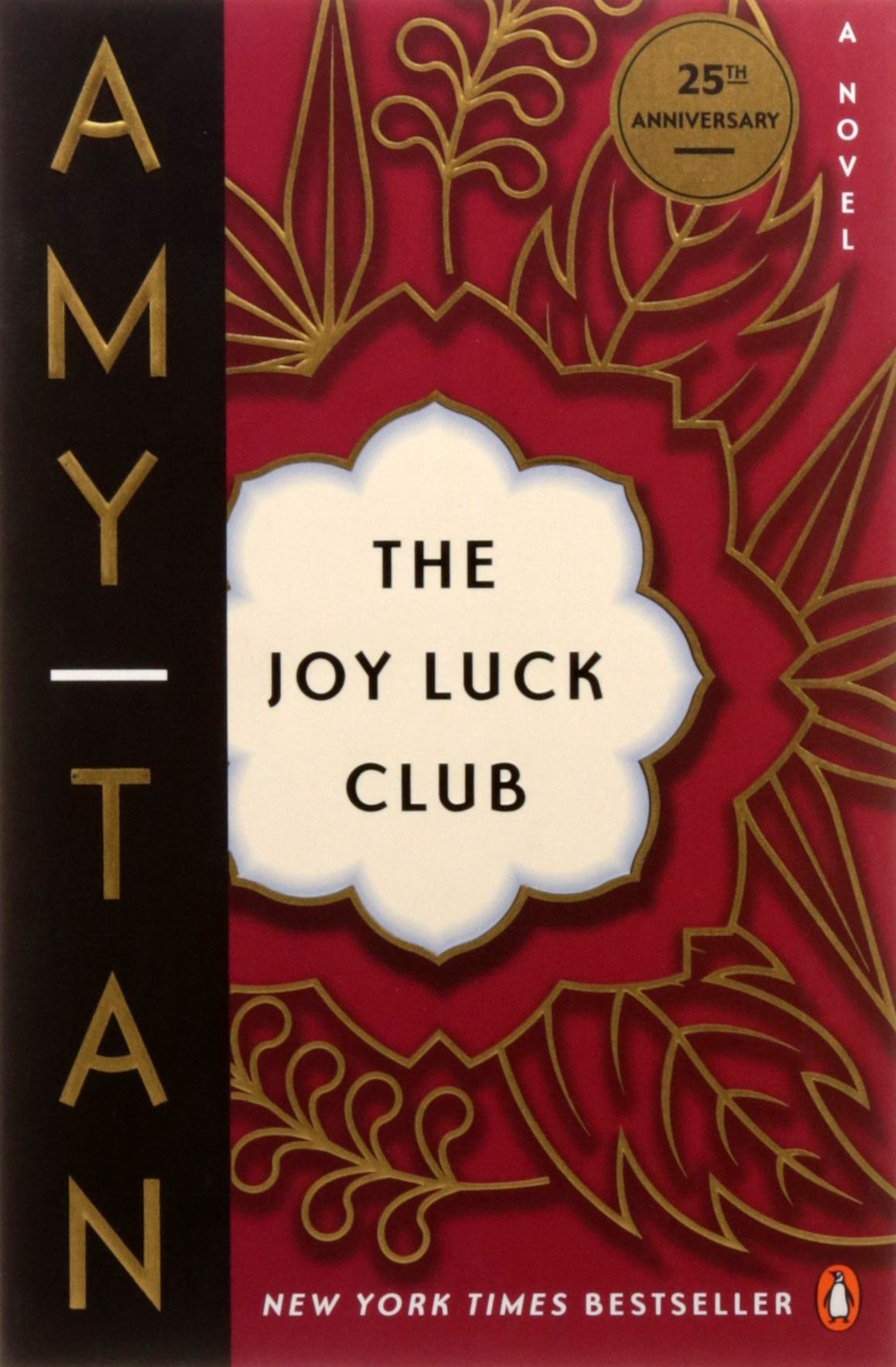

Just as she was embarking on this new career, Tan’s mother fell ill. Amy Tan promised herself that if her mother recovered, she would take her to China, to see the daughters who had been left behind almost 40 years before. Mrs. Tan regained her health, and mother and daughter departed for China in 1987. The trip was a revelation for Tan. It gave her a new perspective on her often-difficult relationship with her mother, and inspired her to complete the book of stories she had promised her agent. On the basis of the completed chapters, and a synopsis of the others, Dijkstra found a publisher for the book, now called The Joy Luck Club. With a $50,000 advance from G.P. Putnam’s Sons, Tan quit business writing and finished her book in a little more than four months.

Upon its publication in 1989, Tan’s book won enthusiastic reviews and spent eight months on The New York Times bestseller list. The paperback rights sold for $1.23 million. The book has been translated into 17 languages, including Chinese. Her subsequent novel, The Kitchen God’s Wife (1991), confirmed her reputation and enjoyed excellent sales. In the following years, Amy Tan published two books for children, The Moon Lady and The Sagwa, and two more novels: The Hundred Secret Senses (1995) and The Bonesetter’s Daughter (2001).

In 2003, she published The Opposite of Fate: A Book of Musings, an autobiography in which she disclosed her experience with Lyme disease, a chronic bacterial infection contracted from the bite of a common tick. Amy Tan’s case went undiagnosed for years before she received proper treatment, and she suffered intense physical pain, mental impairment and seizures. For years, Lyme disease made it impossible for Amy Tan to continue writing. With medication, she has been able to control the worst symptoms of her illness, and has resumed writing, but she also spends much of her energy raising awareness of Lyme disease, promoting its early detection and treatment, and advocating for the rights of Lyme disease patients.

With her illness under control, Amy Tan has completed two works of fiction. Her novel Saving Fish from Drowning appeared in 2005. In 2013, she published one of her most ambitious books to date, The Valley of Amazement, an epic saga told from the point of view of a part-American girl raised among the courtesans of Shanghai in the first years of the 20th century. Tan published a powerful memoir, Where the Past Begins, in 2017. The book recounts her difficult childhood and complex relationship with her mother, as well as her evolution as a writer and collaboration with her longtime editor Dan Halpern, in an intense exploration of the relationship between memory and creativity.

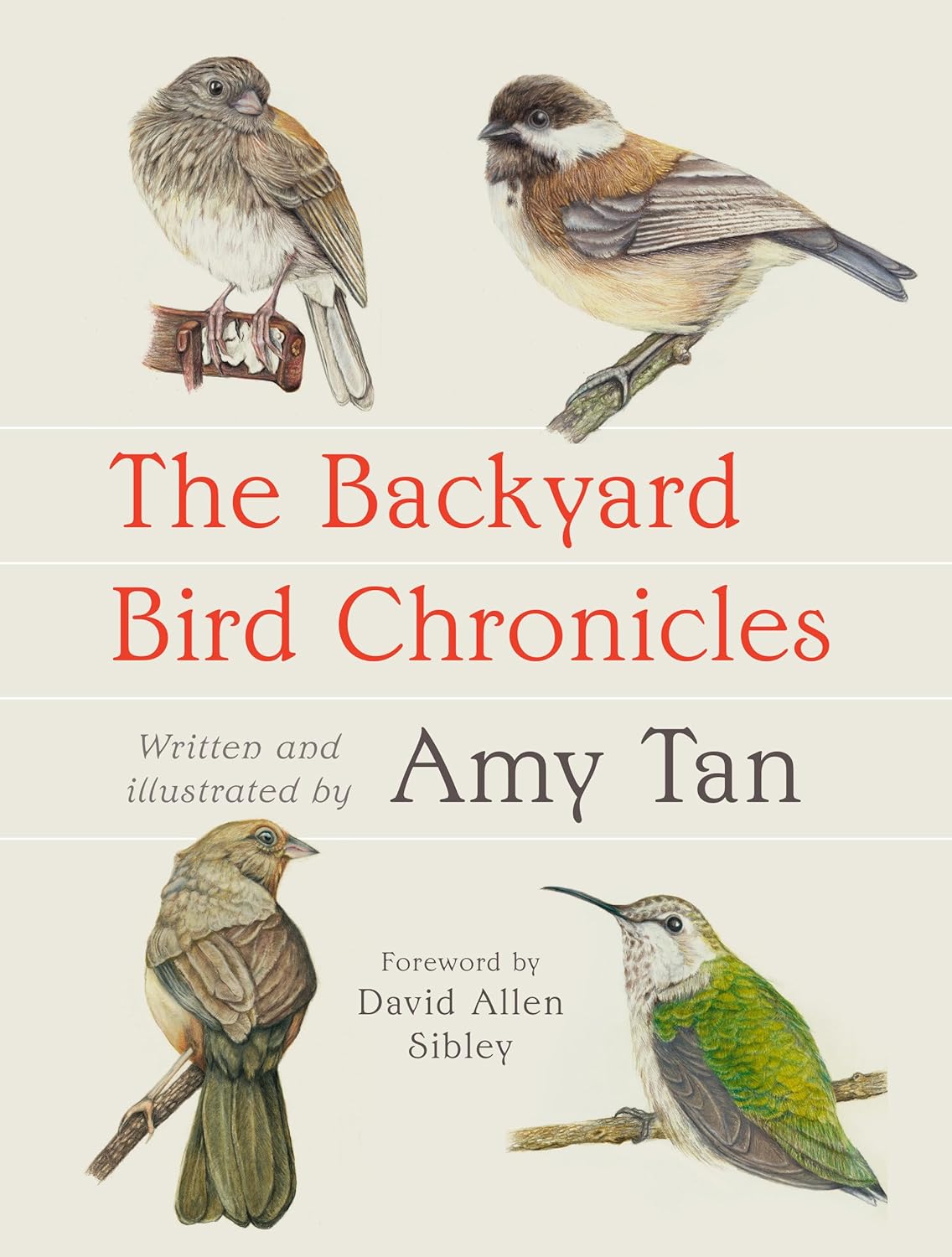

In 2024, Amy Tan released The Backyard Bird Chronicles, a reflective work on her birdwatching experiences. The book maps the passage of time through daily entries, offering thoughtful questions and original sketches. Amid the divisiveness of social media in 2016, Tan found solace and connection to nature through birding, evolving from a personal quest for peace into a deeper appreciation of the natural world around her.

In 1988, Amy Tan was earning an excellent living writing speeches for business executives. She worked around the clock to meet the demands from her many high-priced clients, but she took no joy in the work, and felt frustrated and unfulfilled. In her 30s, she took up writing fiction. A year later her first book, a collection of interrelated stories called The Joy Luck Club was an international bestseller, and Amy Tan’s life was changed forever.

Her subsequent books, The Kitchen God’s Wife and The Hundred Secret Senses, have been bestsellers, and the film of The Joy Luck Club was an unprecedented success. At the height of her success, Amy Tan was stricken with Lyme Disease. Although the infection went untreated for many years, she has overcome the devastating symptoms of this chronic illness and has continued to write bestselling novels, including Saving Fish From Drowning and The Valley of Amazement.

Only 30 years ago, a list of well-known American authors would have included virtually no Asian-Americans. Today Amy Tan is one of America’s most popular novelists. Although they are primarily concerned with the lives and concerns of Asian-American women, her stories have found an enthusiastic audience among Americans of all backgrounds, and have been translated into 35 languages.

How did you come to write The Joy Luck Club?

Amy Tan: I wanted to write stories for myself. At first it was purely an aesthetic thing about craft. I just wanted to become good at the art of something. And writing was very private. I also thought of playing improvisational jazz and I did take lessons for a while. At first I tried to write fiction by making up things that were completely alien to my life. I wrote about a girl whose parents were educated, were professors at MIT. There was no Joy Luck Club, it was the country club. I tried to copy somebody’s style that I thought was very clever. I thought I was clever enough to write as well as these people, and I didn’t realize that there is something called originality and your own voice.

One day, after being told one of these stories didn’t work, I thought, “I’m just going to stop showing my work to people, and I’m just going to write a story. Make it fictional, but they’ll be Chinese-American.” What amazed me was: I wrote about a girl who plays chess, and her mother is both her worst adversary and her best ally. I didn’t play chess, so I figured that counted for fiction, but I made her Chinese-American, which made me a little uncomfortable. By the end of this story I was practically crying. Because I realized that — although it was fiction and none of that had ever happened to me in that story — it was the closest thing of describing my life. Of the feelings that I had, of these things that my mother had taught me that were inexplicable or had no name. This invisible force that she taught me, this rebellion that I had. And then feeling that I had lost some power, lost her approval and then lost what had made me special. It was a magic turning point for me. I realized that was the reason for writing fiction. Through that, this subversion of myself, of creating something that never happened, I came closer to the truth. So, to me, fiction became a process of discovering what was true, for me. Only for me.

I went to a writer’s workshop. I met a wonderful writer there named Molly Giles. She looked at my work and said, “Where’s the voice? Where’s the story? There’s so many things that are happening that are not working, but there’s a possible beginning. If I were you, I would start over again and take each one of these and make that your story. You don’t have one story here, you have 12 stories. 16 stories.” She was right because those 16 stories became The Joy Luck Club.

I was at a stage where that kind of criticism didn’t dishearten me at all. It made me so excited because she had said it in the most constructive way — not simply saying, “This isn’t working, this is bad, this is nothing.” She said, “Look at this. Here you have a voice, and it’s inconsistent with this voice, but it’s an interesting voice. So maybe you should think about this question, what is your voice?” That’s a question I still ask myself today as a writer.

I had an agent who, by luck, read my stuff in a little magazine and wanted to be my agent. Believed in me as a fiction writer before I ever believed in myself. In fact, I told her, when she wanted to be my agent. I said, “I’m not really a fiction writer. I don’t need an agent. But if I ever write anything else, maybe ten years from now, I’ll let you know.” She pursued me, and she kept saying, “You have to write more fiction.” I said, “I can’t pay you anything.” She said, “I’m by commission. You don’t have to pay anything until you sell anything.” I said, “Well fine. You want to be my agent and not make anything.” I thought, “Boy, is she dumb.” She hounded me until I wrote a couple more stories, and then she sold that as a collection called The Joy Luck Club.

You’ve spoken of another turning point. In 1987 you traveled with your mother to China, where you had never been. What did you learn from that trip that was so important to you?

Amy Tan: I took this trip to China as a way of fulfilling a promise. I thought my mother was going to die, and I had sworn to God and Buddha and whatever spirits are out there that I would do this if she lived. And by God the little mother pulled through, so I went to China.

I was nervous about it because it meant three weeks with my mother, and I had hardly spent more than a couple of hours alone with her in the last 20 years. So it was a chance for me to really see what was inside of me and my mother. Most importantly, I wanted to know about her past. I wanted to see where she had lived, I wanted to see the family members that had raised her, the daughters she had left behind. The daughters could have been me, or I could have been them.

And I did see all of those things, and even more. I discovered how American I was. I also discovered how Chinese I was by the kind of family habits and routines that were so familiar. I discovered a sense of finally belonging to a period of history, which I never felt with American history.

When you read about the Civil War, a lot of people, like my husband, can say my great-great-grandfather fought in that war. We have the gun and all that kind of stuff. I have a good imagination, but I could never imagine my ancestors having been in any of this history because my parents came to this country in 1949. So none of that history before then seemed relevant to me. It was wonderful going to a country where suddenly the landscape, the geography, the history was relevant. That was enormously important to me.

It doesn’t necessarily have to be that way for everybody, but for me it was extremely important because I had spent so long denying that side of me. In fact, one of the subjects I hated the most was history. I thought it was completely a waste of time. It had absolutely no relevance. Today, I love history. I find it is absolutely relevant to everything that is going on. It’s not just some philosophical babble of how things repeat themselves. You see the undercurrents of change and culture and that is history. It’s those behaviors that are important. History really is a record of behaviors and intentions and actions and consequences.

So, I think going to China was a turning point. I couldn’t have written The Joy Luck Club without having been there, without having felt that spiritual sense of geography.

Was it also a turning point in your relationship with your mother?

Amy Tan: Oh yes. For example…

I used to think that my mother got into arguments with people because they didn’t understand her English, because she was Chinese. And I saw in China that she got in arguments with Chinese people. She was just as difficult in China as she was in America. I had to laugh about that. There are so many things that I could laugh about and see that my sisters were the same way, that we had inherited things from my mother. But there were differences as well. And my sisters, who had grown up thinking that they had been denied this wonderful, loving, nurturing mother who would have understood everything and been sweet and kind and never would have criticized them. Well suddenly they were shocked to find this mother saying, “You didn’t cook this long enough,” or “This is too salty,” and “Why do you wear that? It makes you look terrible.” They were shocked too. It had nothing to do with being American. They were daughters, also wanting their mother’s approval, and didn’t understand why their mother was so critical. So I saw my mother in a different light. We all need to do that. You have to be displaced from what’s comfortable and routine, and then you get to see things with fresh eyes, with new eyes. The new eyes can be very useful in breaking habits of relationships, the old irritations, the patterns of avoidance. You start talking about things. You still get into fights but you learn to just pick what’s important and say, you know, it’s not so important really for me to win this one. Really, what my mother wants is for me to think that what she has to say is valuable. That’s all.

So I saw my mother in a different light. We all need to do that. You have to be displaced from what’s comfortable and routine, and then you get to see things with fresh eyes, with new eyes. The new eyes can be very useful in breaking habits of relationships, the old irritations, the patterns of avoidance. You start talking about things. You still get into fights but you learn to just pick what’s important and say, you know, it’s not so important really for me to win this one. Really, what my mother wants is for me to think that what she has to say is valuable. That’s all.

Then there was The Joy Luck Club and endless weeks on the bestseller list. Many people are smart and have talent and potential. Why do you think it is that you succeeded, when not everybody does?

Amy Tan: You know, I get asked that question a lot and I never know the answer. The answer keeps changing. Sometimes I think that it’s pure luck, I won the lottery. Sometimes I think it’s because I’m a baby-boomer and what I wrote about are very normal emotions and conflicts that many people have, so somehow it struck a universal chord.

I think that I was in the right time and the right place. I met the right people, who were passionate about my work and, thus, able to get it in front of people who would sell the book in bookstores, readers who would pass the word along to their mothers or daughters or friends. I think it’s all of that.

I also begin to think there are things in life that we don’t understand, that are a mystery. I give credit to something beyond me. I’m not sure what that is exactly, except I think it’s a very benevolent force.

A lot of bad things have happened in my life. I never believed the sort of pap that ministers would say. You know, “Bad things happen for certain reasons. God decided to take your brother at this time for a reason.” I thought, “Bullshit, why would somebody allow such pain to happen to anybody?” It’s so difficult. We don’t have words to explain why things happen, and you can’t couch them in terms like that and explain them at the moment that they happen. It’s only later that you see what the connections might have been and how it led to something.

I think that’s why I’m a storyteller. I take all these disparate events and I have to connect them. I have to make them seem inevitable and yet surprising and plausible. That’s what I think life is like, too. I have the luxury to do exactly what it is we all need time to do, and that is just think about the mystery of life.

Speaking now only of your writing career, what setbacks or detours have you had along the way and how have you dealt with them and learned from them? Self-doubts, fear of failure?

Amy Tan: I didn’t fear failure. I expected failure. I think I’ve always been somebody, since the deaths of my father and brother, who was afraid to hope. So, I was more prepared for failure and for rejection than success. The success took me by surprise and it frightened me. On the day that there was a publication party for my book, I spent the whole day crying. I was scared out of my mind that my life was changing, and it was out of my control, and I didn’t know why it was happening. I thought it would ruin things, because at that moment in my life I was fairly happy. I was getting along with my mother. My husband and I had been married for a long time, we were happy, we had our first house, we had great friends, we were doing well, we weren’t starving. We had a comfortable living, and I thought, “Things are going to get messed up here, and I have no control over this.” I could already see how people were treating me differently. That’s the scary thing. You know, when people say, “How has success changed you?” you have to say, “No. How have people changed toward you as the result of success?” And “How have you dealt with that change in how people have changed toward you?” That’s the most difficult thing.

So I went through a terrible period of feeling that I had lost my privacy, that I had lost a sense of who I was. I was scared by the way people measured everything by numbers: where I was on a list, or how many weeks, or how many books I had sold. By the time it came to the second book, I was so freaked out, I broke out in hives. I couldn’t sleep at night. I broke three teeth grinding my teeth. I had backaches. I had to go to physical therapy. I was a wreck!

I started a second novel seven times and I had to throw them away. You know, 100 pages here, 200 pages there, and I’d say, “Is this what they liked in The Joy Luck Club? Is this the style, is this the story? No, I must write something completely different. I must write no Chinese characters to prove that I’m multi-talented.” Or “No, I must write this way in a very erudite way to show I have a way to use big words.” It’s both rebellion and conformity that attack you with success. It took me a long time to get over that, and just finally being able to breathe again and say, “What’s important? Why are you a writer? Why did you write that book in the first place? What did you learn? What did you discover? What was the most rewarding part of that?” Don’t think of what’s going to happen afterwards. If it’s a failure, will you think what you wrote was a failure, that the whole time was wasted? If it’s a success, will you think the words are more valuable? That crisis helped me to define what was important for me. It started off with family. It started off with knowing myself, with knowing the things I wanted as a constant in my life: trust, love, kindness, a sense of appreciation, gratitude. I didn’t want to become cynical. I didn’t want to become a suspicious person. Those were the things that helped me decide what I was going to write.

My mother, meanwhile, all the time kept saying, “Write my true story. That’s all you have to do. Write my true story.” I kept saying, “No, that’s not fiction. I’m not writing biography.” Writing is an extreme privilege, but it’s also a gift. It’s a gift to yourself, and it’s a gift of giving a story to someone. What better gift can I give my mother than to finally sit down and listen to her entire story, hour after hour after hour? She’s very repetitive. This is hard work, listening to her say the same laments in her life over and over again, but this time asking for more details. Getting this story out, I realized, was a gift that she was giving me. And there was a gift I could give back to her, and it didn’t matter what happened to that book afterwards. If it didn’t sell a single copy, if it was panned, that whole time I spent writing it, getting to know my mother, getting to know myself, all of it was worth it. Nobody — no review, no place on a list — could take that away from me or make it more important than what it already was.

I still have to think about that over and over again, with everything I do in life. It’s so easy to get derailed by success. You get distracted. You get opportunities. If I look back ten years ago, 15 years ago, I would not be able to believe that I would be saying, “No, I don’t want to make another movie. No, I don’t want to do a TV series.” You can get sucked into the idea that, “Gosh, this is impressive. Maybe I should do this. It will look good.” Or “I’ll write like this because it will impress that critic.”

I think a lot about death because of what’s happened in my life. And I like to hope that there is something after death. And I like to hope that if there is something afterwards, the people I love will be there. So, I say, “If I die, who’s going to be waiting for me on the other side — that critic, or that movie producer, or that TV exec? Or is it going to be my mother and my husband and my brother?” Gosh, it simplifies things a whole lot. It’s just crystal clear what’s important.