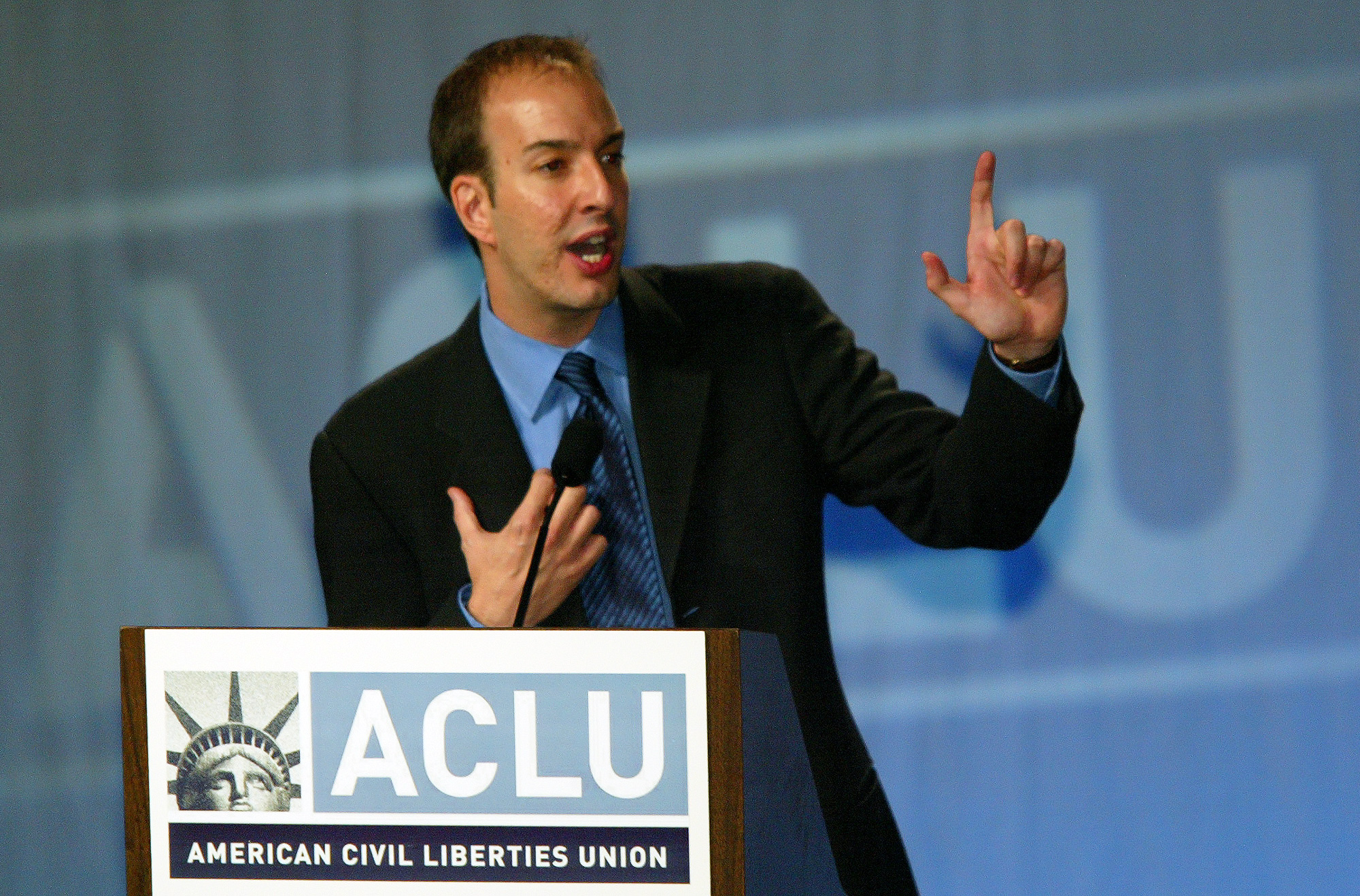

Anthony Romero: The struggle for civil rights and civil liberties is really a very basic one. It’s one we all understand. We have the right to live with dignity. Each of us — regardless of who we are, or what background we come from, or what religion or what race — have a right to determine how we think about the world, what we say, whom we love, who we associate ourselves with. It’s the ability to tap into that most beautiful part of the human experience, of saying, “I decide what I want to be and what I do and what I say and what I think.” We all feel that, we all feel the sense of personality, of individuality, and the idea then that there are barriers that impede our ability to live our lives fully, there are barriers that impede our ability to be all we can be. That’s what we do, we remove the barriers, we remove the blocks. It’s about taking every person whose life is precious and making sure that they can make the most of it as they wish. That’s, in the end, what we do every day.

What do you find to be the most productive way to go about solving problems?

Anthony Romero: I think the most productive way of solving problems is to hear all sides, that you have to hear different points of view. That if you only listen to the viewpoints that you agree with, you get half the picture. That’s why the ACLU is so significant. It’s an organization that believes in the freedom of speech, and that democracy can be a great many things, but it can never be a quiet business. And the reason why that is, is because we want everyone to be able to access all different viewpoints, all different analysis, and then you sort out how you think about something, what you think. That’s very personal to the person. I think in the end, whenever you tackle a problem, whether it’s at the political level or at the personal level, the societal level, you have to hear the different viewpoints. You have to consider what different people will say. Sometimes you learn more from your critics than you do your allies, and that is an essential part of what we do every day. We try to take apart a very complex issue, to try and understand why our opponents think the way they do, and why we think the way we do, and how best to bring about an understanding of these issues. I think we have to ask the tough questions, you have to kick the tires. You can’t take anything for a sacred cow. You have to be willing to consider the alternatives, and then you make up your mind.

How do you evaluate competing points of view? How do you decide which side you are going to come down on, or how you’re going to argue?

Anthony Romero: In law, it’s pretty easy to consider different points of view. That’s our job. We have to hear the opposing side and we have to respond to it. When we hear arguments, either for or against a particular issue, or for or against a particular case, we have to make up our minds as to what we think makes sense.

I think it’s also important to have your ear to the ground in terms of how people think and feel about a particular issue. Lawyers can be very esoteric, can be very abstract, some of these issues. You have to hear how people think about it, how they experience it in their everyday lives. Then you have to be able to communicate that to people, because you can win in courts, and you can win in Congress, but if you lose in the court of public opinion, you lose the battle. That is why it is so essential for us to talk about the work we do, why we do the work we do, what we are hoping to accomplish, and being able to tell the story. Good lawyering is great storytelling. There’s a good guy — that’s us. There’s a bad guy, the opponent. There is some type of orbiting force, a court, good versus evil. There is a denouement, there is a resolution. Either the good guys win or the bad guys win, and then we get to fight another day. So if you can tell the narrative in such a way that you tell people why this is important, and help them think through, “Well, why would this matter to me? If I am not that person, why would I care?” But the fact is that the American public, we are a very fair people. We are a good-hearted people, we are an altruistic people. We are an idealistic nation. We believe it can always be better. That’s the promise of this country. That’s the great history that we have come through. So you can appeal to the best of people’s intentions, the best of their heartstrings, and you give them a role to play. You give them a reason to care, you give them a role to play. You give them a reason to think that the world can be better and different. Then you make change and then you make momentum.

How do you conceive of fairness or justice? Has your conception evolved over time?

Anthony Romero: Fairness is something we feel, whether we’re in the supermarket and someone tries to cut in front of us in line, or whether we’re trying to make sure that our kids get their fair shake at school if a teacher is being unfair or punishing our kids. We all feel it. We all know that when we feel the victim of unfairness. We think it’s awful, we think it’s wrong. In a lot of respects, what you’re tapping into is that moral compass that each of us has. You’re trying to help people understand how their own personal moral compass affects other people, and that there has got to be a societal moral compass.

Each of us feels fairness in a very personal way. We feel it in our everyday lives. And the idea of our work is to make sure that people understand the idea that — not just their own personal fairness, but what is fair for other people? A decision I make for myself may be the right one for me, but may be the wrong one for another person. Is it fair for me to impose my decision onto someone else’s life? So part of what we have to do is we have to help people understand how it is deeply personal, the work we do, but how it’s relevant for everyone. There can’t be one size fits all for everyone.

Also, fairness evolves. Our notion of fairness in America is very much evolved, in the beginning. We were a great democracy built on fighting the tyranny of a king. The people who had their rights were white propertied men. And over more than two centuries that “rights of the citizen” would evolve to include women, to include blacks, to include different groups that were not ever part of the initial social compact. So the idea of fairness is one that continues to evolve as our society continues to evolve, as our sense of possibility continues to evolve. It’s not a static viewpoint. I think that’s the beauty of this work, it’s just that we will never be done with it. We should never be done with it. For as long as we have an America, we’re going to need an ACLU. We’re going to need lawyers who are going to push the boundaries of what fairness and equality and dignity really mean in society at the time. And that’s the work we do, in and out, every day of our life.

Do you think that there are things that we need to do, as a society, to reaffirm or rehabilitate that social compact? Do we do enough to maintain it among ourselves?

Anthony Romero: I think what is terribly sad is that the notion of the social compact is fundamentally breaking down in politics. Politics has become so polarized. There are the winners and the losers, and there is not an understanding of the importance of compromise in politics. Yet the social compact requires us to talk about compromise, to talk about the need for meeting everyone else halfway, to understanding why these issues may be important for someone else, even if they are not relevant for us. I think each of us is taught certain key aspects of the social compact when we grow up. I grew up in a very Catholic household. The Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” That’s what this is about: the ability to be treated fairly, to treat others the way you would want them to treat you if the shoe were on the other foot.

I think we have to keep tapping into those basic notions of what is fair, of what is right, what is good, what should be a part of the social compact. Sometimes we attach it to laws and regulations or politics or political parties, and that is often the wrong source. Because those are always up for grabs and up for debate, or being put down or denigrated. But when you’re tapping into the best of the human spirit, “Why is this important? Why is it important that we allow people to be involved in loving, committed relationships recognized by the law?” Even if I’m very heavily religious, and I don’t believe that I would want my kid to be gay or marry another same-sex partner, as an American I want the law to recognize people’s decisions, and to value their decisions and to value their rights. And to make sure that when you have a committed loving couple that made the decisions for themselves, that the law should not treat them like strangers. That they should have the full protections of the law, just like my mom and dad did. When we make those arguments that way — and not political arguments, and not arguments that deal with the partisan politics — but deal with the very basic nucleus of why is this right. Even if it’s not right for you, is it right for someone else? If it might be right for someone else, then is it right for you not to let that other person live life that way? I think that’s the conversation we need to have more and more.

In making these arguments, communicating to others, is there a role for creativity?

Anthony Romero: Lawyers are not normally known as being creative people. But you know what? We are, we are. We are about creating rights and creating opportunities where they don’t exist. We are about looking at the most serious systemic structural barriers and trying to find a solution. We are about envisioning a world not that is, but that should be. So when you look at a social problem and you say, “Okay, why are the schools delivering such poor educational outcomes for our kids?” And as a lawyer you come in and say, “Okay, how are we going to solve it? How do we make sure that there is more money going to the poor classrooms and that the teachers are better trained, that there are better resources for students, that we equalize between the rich schools and the poor schools?” You have to approach this with creativity. You have to approach this with a sense of possibility.

This is not just about counting the numbers that are on the ledger; this is about looking at the world and seeing what it is and seeing what it should be. And then you have to figure out creative ways of getting there, and sometimes you have to make it up, you have to try it. Who would ever have guessed that the law would ever recognize the rights of women? When the ACLU was founded in 1920, women didn’t have the right to vote. Blacks were second-class citizens by rule of law. There was no discussion of the rights of gay people. Gay people existed, obviously, but there was no discussion of the rights of gay people. The law has been such a creative force for helping us understand what we should be, not just what we are, not the reasons why we are stuck in a place, but to think about the ways in which we could overcome and supersede our challenges and our difficulties. So the best lawyers are creative ones. They are saying, “Okay, this is what it is. What should it be, and how do I convince someone to get us there?” And you think of the different ways you can do it. And sometimes you lose, sometimes you fail. Sometimes you have to fail to be able to come back and fight the battle another day. But the creativity is all about the human existence. And if we lose sight of the fact that creativity is an essential part of what each of us does, then why live?

What kinds of setbacks have you had along the way in pursuing the issues that have mattered to you, and what did you learn from those setbacks?

Anthony Romero: I think about our work at the ACLU almost like a baseball team. I have never played baseball, but I watch it, and a good baseball player, if he’s hitting three times out of ten up at bat, it’s a good batting average. So I try to think about it that way: three times out of ten we win. We win more than that usually. The fact is that we have to think about the impact of it long-term. We have failed seven times up at bat, and we strike out, and I think, “How can I learn from that failure? What went wrong? What could I have done differently?” You have to take it apart to understand your failures. Failures teach you much more than your successes. Sometimes it is better just to pause on a setback, on a failure, on a screw-up, and say, “What did I learn from this?” You learn how to do it better and you recommit yourself.

I am privileged to represent an organization that will be here forever. It’s a permanent fixture in the American political landscape. We’ve been here for 92 years. We have outlived every president since the early 20th century. We have sued them all. The fact is, as long as we have a constitution, as long as we have the United States of America, we’re going to need an ACLU to defend the rights of all people, and we’re going to be there forever. We can lose a case, like Bowers v. Hardwick in 1986, where the rights of a gay couple to have consensual sex in the privacy of their bedroom was — that was being criminalized and that statute was being upheld by the Supreme Court — until today, where the courts are on the verge of recognizing full equality for gay and lesbian people. You have to lose in ’86 to win in 2012. The fact is, this organization is going to be around in 2022, ’32, ’42. I’ll be old or dead, but I know that the spirit of this work will continue. That is what gives me courage, that even when I lose today, we know we’re going to be back in there at some other point, pushing the envelope and making it right at some other point in the future.

How is failure a good teacher? How is it that you can learn more from your failures than your successes?

Anthony Romero: The failures teach you what you could have done differently, what you didn’t anticipate, what you misjudged, how worthy your opponents are. The successes? We can learn from them too. We can learn the importance of celebrating successes. Sometimes we don’t stop enough to smell the roses when we win, and we’re off to the next battle. But with failures, you have to sit with it, you have to unpack it. Why didn’t this go down very well? What could we have done differently? If we could do a rewind, how would I play back the tape differently? It’s an essential part of what we do to make social change, to understand the failures in one context so you can succeed at some later point, and make sure you don’t repeat the same failures.

If we don’t learn from our failures, then we’re doomed to create them over and over again. And what’s the point of that? We want to win. So if you fail once, take the time out to learn. Take the time out to ask the questions, take the time out to be analytic and self-critical. All of us have failed. I mean — Christ! I have. Today, I have failed more than I would like to imagine on a couple things. Yet there are moments when you say, “Okay, I can do better.” We have to focus on the idea that it’s progress, the idea that we can make a difference. I think there’s also a bit of humanity in it, there is a bit of humility in it. That if we don’t ever learn from our failures and don’t recognize that we’re going to fail, then we have an overblown sense of who we are. That’s not very good, because arrogance is what comes before the fall. So I think it’s important to approach this work with optimism, with energy, with creativity, with tenacity, with a sense of humor. Oh God, if we stop laughing, that’s really a sorry state of affairs. And a willingness to learn from one’s mistakes.

One of the issues that comes up frequently these days is privacy, because the world of social media is transforming our understanding of privacy. What do you see as the challenges and issues for protecting privacy in the 21st century? Is social media transforming the privacy landscape?

Anthony Romero: The notion of privacy is one that is very important to the American people. It goes to the beginning, the idea that the man or woman is the sovereign over his or her castle. The idea that the colonists were very clear that the government couldn’t force their way into their homes, into their lives. And that we understood the importance of having that sanctity of that private space. That’s why there are certain key things about the Fourth Amendment, the protections against unreasonable searches and seizures, and that the government can only force you to quarter soldiers in times of war. Very clear parameters, like “Thou shall not cross this line…” the private line. Now that has evolved over time, and now it’s not just homes, but it’s actually our cars, and it’s actually the Web and the Internet, financial records or medical records. I still think that there is a part of it that we understand, that the right to privacy is the right to be left alone, that you don’t want the government screwing around in your private affairs. And that we understand that if government gets too far into the private affairs of a person, that becomes a very caustic dynamic for a society. That part of the reason why we have great individuality, great creativity, great entrepreneurs, great entertainers, great writers, is because we don’t countenance unwarranted intrusions into our personal sphere.

How we adapt that to the world of the Internet is critically important. For a lot of people, the Internet now is a way that they communicate with their loved ones, with their family members, with their employees, with their colleagues, with the world. Making sure that the law catches up to the way in which we are living our lives, and making sure that we have the same protections over the Internet that we had over our houses, and that the government shouldn’t conduct an unreasonable search and seizure of our inbox on AOL just as it wouldn’t conduct an unreasonable search or seizure of our home. There’s a lot of catching up to do. It’s interesting, because a lot of young people see the communications technology as an essential part of their lives. It’s who they are: “My Facebook page… My Twitter account…” It’s funny, because I grew up in a time when the Internet didn’t exist. I tell that to a lot of interns. I tell them, “When I was in college, your age, there was no Internet.” And they look at you like you’re prehistoric, like a dinosaur. They are never separated from their iPad or from their smart phone. So they see it as an extension of themselves. I don’t know if enough young people really understand the ways in which some of their private expressions — their own personal lives, and their thoughts and their aspirations — could be open for interception by the government, could be open for interception by the private sector. There are two different conceptions of privacy, though: when you deal with the private sector and when you deal with the government.

There’s a huge concern over whether or not these private corporations that amass all of our pictures, all of our text messages, all of our e-mails, whether they should be able to own that data as a way to make money off of our personal communications. That raises very serious concerns. Because I sent an e-mail to someone doesn’t mean I want AOL to be able to read my e-mail and then pitch me a product in the next pop-up ad. But it’s also really quite different with the government, because when the government intercepts our communications, only the government has the ability to take away the most fundamental liberties. Only the government can take away my money. Only the government can take away my liberty. Google can’t imprison me, and Google can’t seize my bank account. The government, however, can. And that’s why our greatest concern is when the government begins to amass data, sometimes collected by the private sector, that can be used against the very individuals who are unsuspecting about certain communications, or certain e-mails. That raises enormous concerns for us as a society. There are moments when you want to make sure that the government just leaves you alone. For a lot of people concerned about privacy, it’s clear why we want to keep that information private.

It seems some people today aren’t really concerned about the right to privacy, or they don’t see how the issue affects them.

A lot of people don’t think about the right to privacy. They say, “Well, I’ve done nothing wrong, why do I care?” It’s not like we’ve done anything wrong, but does each of us want to be judged by the worst statement or the worst action on our worst day? Does each of us want to have stuff that we live to regret put in the hands of someone else? When I answered my mom in an impertinent way, and I’m not really giving her the love or respect she deserves, do I want that irreverence and that childishness to be in the hands of another person? Do I want another person to be able to judge by the wrong thing I said at the wrong moment to a great mom? It’s not that we’ve done anything wrong, it’s the fact that some of these things are inherently personal. So if we see them as personal, we want society to treat them as personal. That’s why we have to put in place protections, to make sure that what I say to you here is as protected as it is when I send you an e-mail.

The government can’t come barging into this door and listen to our conversation without a warrant. They can’t do that. We’re not doing anything wrong. You need to have probable cause. You need to have the judge sign the warrant. If they’re going to barge into this room, you’re going to have to show me why they have a right to intervene in our nice little tête à tête. Well, why should it be different on an e-mail? If I’m sending you an e-mail, why should the government be able to just intercept it without judicial review? Why should my communications to you be open game for anyone else? A different medium, same words. That’s why we have to catch up with these protections. Privacy is so essential, it’s about the person. The right to be private is the right to be who you are. It’s the right to think what you want, to say what you want. The right to be right, the right to be wrong. The right to be a magnanimous individual, the right to be a jerk. So the ability to live a life of privacy is the ability to live life in its fullness. If we don’t have the right to privacy, then our ability to live life fully, without anyone looking over our shoulder or worrying about someone following us or tracking us, that gets jeopardized.

Where do you think your greatest education took place? Was it at Princeton or law school, or was it afterwards? Or were these fundamentally different experiences?

Anthony Romero: I’ve been lucky that I’ve been trained at some of the best schools in America. I’ve gone to Princeton, I’ve gone to Stanford, I had some great teachers in high school. So I love our educational system, and I think that teachers in public schools taught me enormous amounts, and teachers in private universities and private schools taught me enormous amounts. But I have learned in life. I’ve learned on the street, I’ve learned talking to people. It’s the conversations you remember, it’s the people who make you stop and think differently about something. It’s less the classes I took in college and more about the late night conversations or debates about the world that I remember. It’s the conversations you have with people who are struggling in their lives. That one thought from a taxicab driver that just kind of sticks with you and makes you think differently. Or talking to someone who’s about to lose their home and finds themselves in eviction proceedings. Or talking to someone on death row, and understanding how they still find meaning in their life, and why it is important to safeguard the sanctity of life, that life is precious. That there’s even a sense of the human spirit even for people on death row. It’s not the same thing to be on death row as to be executed — there is life, there’s thought. So I’ve learned most from my interactions with the people, conversations with people, traveling overseas, little interactions. Arguments are sometimes places you can learn. You can learn how to be wrong, you can learn how to apologize. So I think life is an education. I think the schools of higher learning and the public schools and the private schools are great, but they’re only training ground for the real education, which is living, which is life, which is the beauty of walking outside a door and confronting something new and unexpected and learning how to adapt to it.

What does the American Dream mean to you?

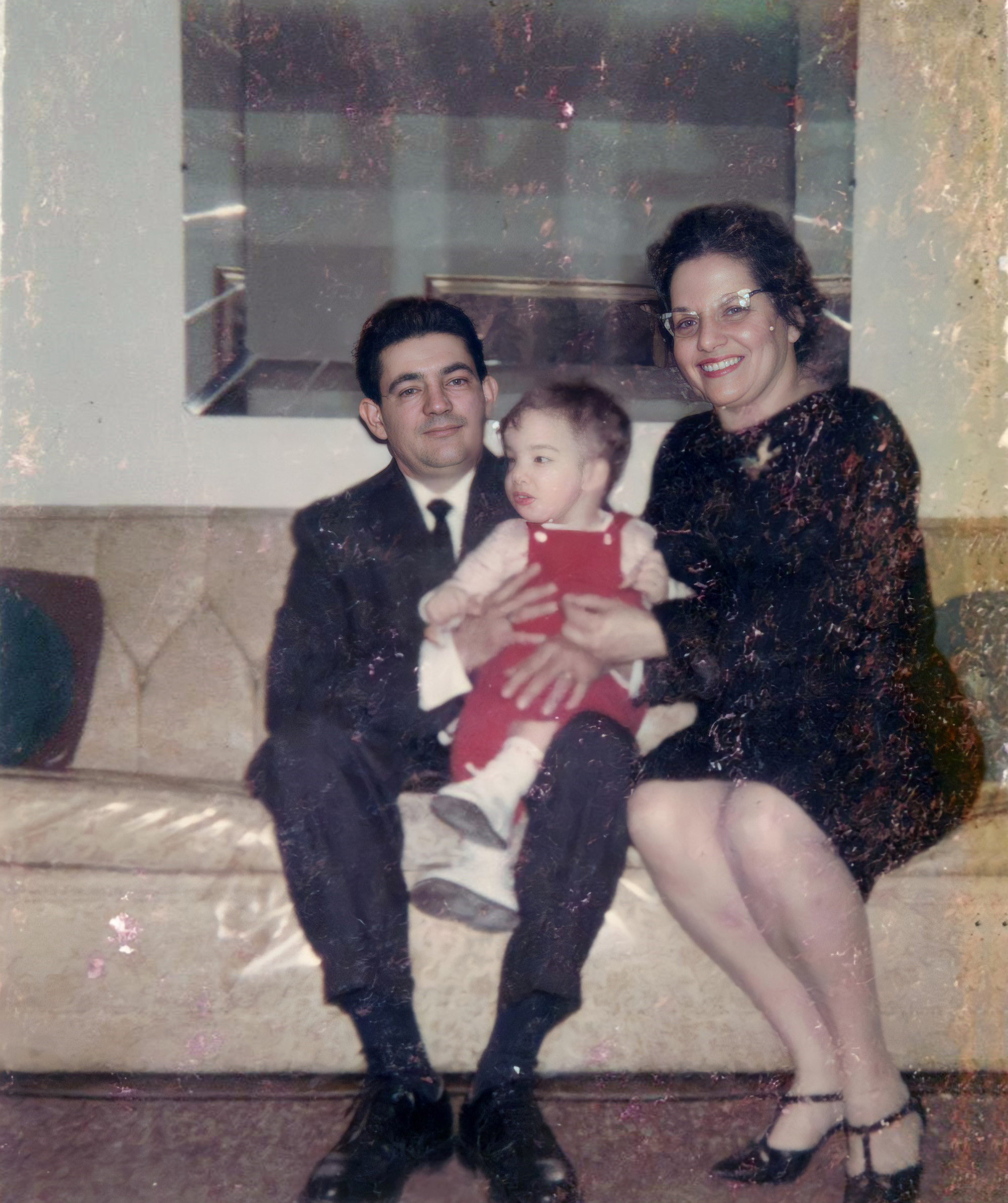

Anthony Romero: The American Dream is about you deciding what it is you want with your life. It’s about seeing all the potential. It’s about making very personal decisions over how we’re going to spend our lives and how we’re going to think about the world. It’s about having full, unfettered ability to think about what we care about and what we do. And of course, there are limits over our ability to affect other individuals, but it’s the idea that the person is sovereign over his or her own body, and that anything is possible. The American Dream gets described as someone who comes from humble beginnings and makes it to the top. And I’ve been lucky in the fact that I started out from a humble background, with great family, and Lord knows I never imagined I would be here talking with you today. So having gone to the best schools, and leading a remarkable organization like the one I lead, is living the American Dream. But the American Dream is every day. The American Dream is being able to walk outside your door and not worry about government surveillance, not to worry about where the next paycheck comes, to be able to think about the potential, the possibility, the learning. So the American Dream is all about possibility. It’s about dreaming. That’s why it’s called the dream. It’s the American Dream, it’s not “the American Promise,” it’s the American Dream. What do you dare dream? What can you imagine in your mind’s eye? What will you do? You can daydream. You can live the dream. You can act the dream. You can make the dream come true. And it’s so much greater than anything we’ve ever been able to describe. It’s not about the next good job, it’s not about the next promotion, it’s not about the next fancy car. The American Dream is about potential of the human spirit, that anyone can do it. That even the most humble among us have a lot to offer and contribute and can dream.

Where would you like to see this country in 15 or 25 years, and where are you worried that we actually might be in 15 to 25 years, as opposed to what you would like to see?

Anthony Romero: I worry about America getting cynical on its own promise. That the land of opportunity, that now maybe we don’t believe in that as much. And the land of possibility is one where there’s possibility for some, but not for all. And that’s not the America we started out creating. I worry that we will accept things like poverty or injustice or discrimination or bigotry as just an ordinary part of life. “That’s the way it is, that’s the way we roll.” That cynicism is enormously frightening. That cynicism would eat away at any ability to make a difference. That cynicism would impede our ability to take the next step forward. This was a country that believed in all potential. We believed that we could fight against the most powerful imperial power, England, and win. We believed we could expand our way throughout the entire northern continent, and we did. We believed we could put a man on the moon. We believed we could find cures to diseases that would strike down my grandparents, and we did. There was nothing that seemed impossible to America at some point. Now there are issues that we think are just impossible to solve. “Poverty? Well that’s just a part of everyday life. Bigotry? Discrimination? Injustice? That’s the way people are.” That resignation, that acceptance of the status quo betrays the American Dream in ways that will stunt our growth. That’s what I most worry about.

I think there is a certain level of cynicism, certainly in our politics. Our politicians too often talk about the realpolitik of making politics. “That’s just the way it is, nothing we can do to change it.” That we have to worry about the folks who can succeed, and focus less on the folks who can’t. I think part of what we have to do is to recommit ourselves, that each and every single person in America is a precious person, whether they are an immigrant or a citizen, whether a woman or a man, whether they are gay or straight, whether they are physically able or disabled. That there is a preciousness of the human existence and that we all have a responsibility to cultivate that in each other, that we are the farmers of that American Dream. That it’s not enough about me growing my own little crop right here, that I am responsible for making sure that the crops of my neighbors grow. That’s the promise of America. And that you hear less and less. That you hear less and less in politics. That you hear in families. That you hear among friends. That you hear in local communities. But we really don’t talk about the possible. We don’t ever talk about tackling the impossible. We don’t ever stretch our sights over what it is that we should accomplish, what makes us feel good.

At the end of the day, America is about a great many things. We are not a people sharing a common language, we are not a people sharing a common religion, we are not a people sharing a common ethnicity or race. We are a people sharing a common dream, a dream that each of us decides individually, but a dream of potential, a dream of change. A dream of achievement, of achieving whatever it is we want. That perfect little sonnet, that big paycheck, that being the greatest mom in the world, that being a committed father or a committed husband. That dream each of us gets to decide for ourselves. And that the law should be a way to help us achieve that dream and not be an impediment. That these things transcend us, and that we’re not asking people to buy into someone else’s definition of what is right or wrong, but to recognize that each of us has the ability to decide for ourselves what is right for ourselves. That it is our collective efforts to unleash that potential in everyone. And that is the America we know and love. That’s the America that is still very much alive and well. Even though our politics doesn’t reflect the good-hearted nature — the optimistic nature, the tenacious underdog nature of the American spirit — that spirit is there. That spirit is there in people, in our clients, in our cases, and the communities, and that’s what we have to unleash. Because our leaders don’t lead, our leaders follow, and we need them to follow our sense of optimism and hope and change. And not for it to be a very cynical or selfish way of thinking about the world, but to really say that the rising tide will raise my boat, and I want my neighbor’s boat to be fully upright in the water. That makes me proud about the country I live in, because that’s who we are. To touch into that again, I think, is the great promise of America.

Beautifully said. Thank you so much for sitting down to talk with us today.