My mom really gave her kids this sense of the possible, this strong sense of self, a sense of community.

The man who would become the 41st Mayor of Los Angeles was born Antonio Ramon Villar, Jr. A third-generation American on his mother’s side, his grandfather immigrated from Mexico early in the 20th century. Young Antonio Villar grew up in City Terrace, one of the neighborhoods making up the unincorporated area of East Los Angeles. His childhood was a difficult one. His father drank to excess and became violent when drunk. Villar, Sr. left the family when young Antonio was five years of age, leaving his mother to raise Antonio and his three siblings on her own. Although the family lacked many material comforts, Mrs. Villar instilled in all her children a respect for education and hard work, and a keen sense of justice and social responsibility. Young Antonio delivered newspapers and worked at other odd jobs to help support the family. At 15, he left his job at a Safeway grocery store to join a picket line supporting the United Farm Workers, who were leading a boycott against the growers of table grapes in California. Although he knew little of their cause at the time, he identified with the farm workers and their struggle. He later participated in the organized walkouts of Mexican-American high school students, protesting discrimination in the school system and the larger society.

At age 16, a benign tumor in his spinal column temporarily paralyzed him. When he recovered and returned to his Catholic high school, he was no longer able to participate in organized sports and became increasingly alienated from school, his peers and society in general. By his own account, suppressed anger from his father’s abusive behavior contributed to his violent temper, and the teenage Antonio increasingly responded to frustration and difficult situations by lashing out violently. Expelled from Cathedral High School, he transferred to a public high school but quickly dropped out again when he was assigned to vocational classes rather than the college preparatory courses he had taken at Cathedral. He continued getting into fights and appeared to be caught in a downward spiral. His mother eventually persuaded him to return to school, where he caught the attention of a sympathetic English teacher, Herman Katz. With Katz’s encouragement and support, he took extra classes in the evenings and graduated on schedule. He entered East Los Angeles College, where his grades improved and he was able to transfer to the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

At UCLA, Tony Villar, as he was then known, was active in student politics and the movement opposing U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. After graduating with a degree in history, he studied at the People’s College of Law, but failed to pass the California bar exam. With his ambitions for a legal career on hold, he became a field representative and organizer for the United Teachers of Los Angeles (UTLA). Over the next few years he won a reputation in labor circles as a gifted advocate. He became President of the Los Angeles chapter of the American Federation of Government Employees, and of the local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. In 1987, Antonio Villar married Corina Raigosa. The couple elected to merge their surnames, and would henceforth be known as Antonio and Corina Villaraigosa.

As a rising star in the labor movement, Antonio Villaraigosa became a familiar face to the city’s elected officials. In 1990, he was appointed to serve on the board of the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transit Authority, where he worked alongside the elected County Supervisors, as well as the Mayor of Los Angeles and members of the city councils of Los Angeles and neighboring cities. Villaraigosa’s friends in labor and local government had long urged him to consider running for public office, and the introduction of term limits to the California state legislature in the 1990s created just such an opportunity. In 1994 he entered the race for an open Assembly seat representing much of Northeast Los Angeles. Although he was opposed by the outgoing Assembly member and his allies in Sacramento, Villaraigosa won an upset victory in the Democratic primary and was easily elected in the general election.

In Sacramento, Villaraigosa quickly joined his party’s leadership team. In his first term, he was named Assistant Majority Leader (or whip) and by the end of his term was serving as Majority Leader. In 1998, he was elected Speaker of the Assembly. Term limits forced him to leave the Assembly in 2000; the following year he made his first run for Mayor of Los Angeles. He came in first in the initial round of voting, but was defeated by fellow Democrat James Hahn in a run-off. Villaraigosa won election to the Los Angeles City Council in 2003, defeating the incumbent councilman. Mayor Hahn’s firing of police chief Bernard Parks, an African American, cost the Mayor crucial support among African American voters, and Villaraigosa prepared for a rematch in 2005.

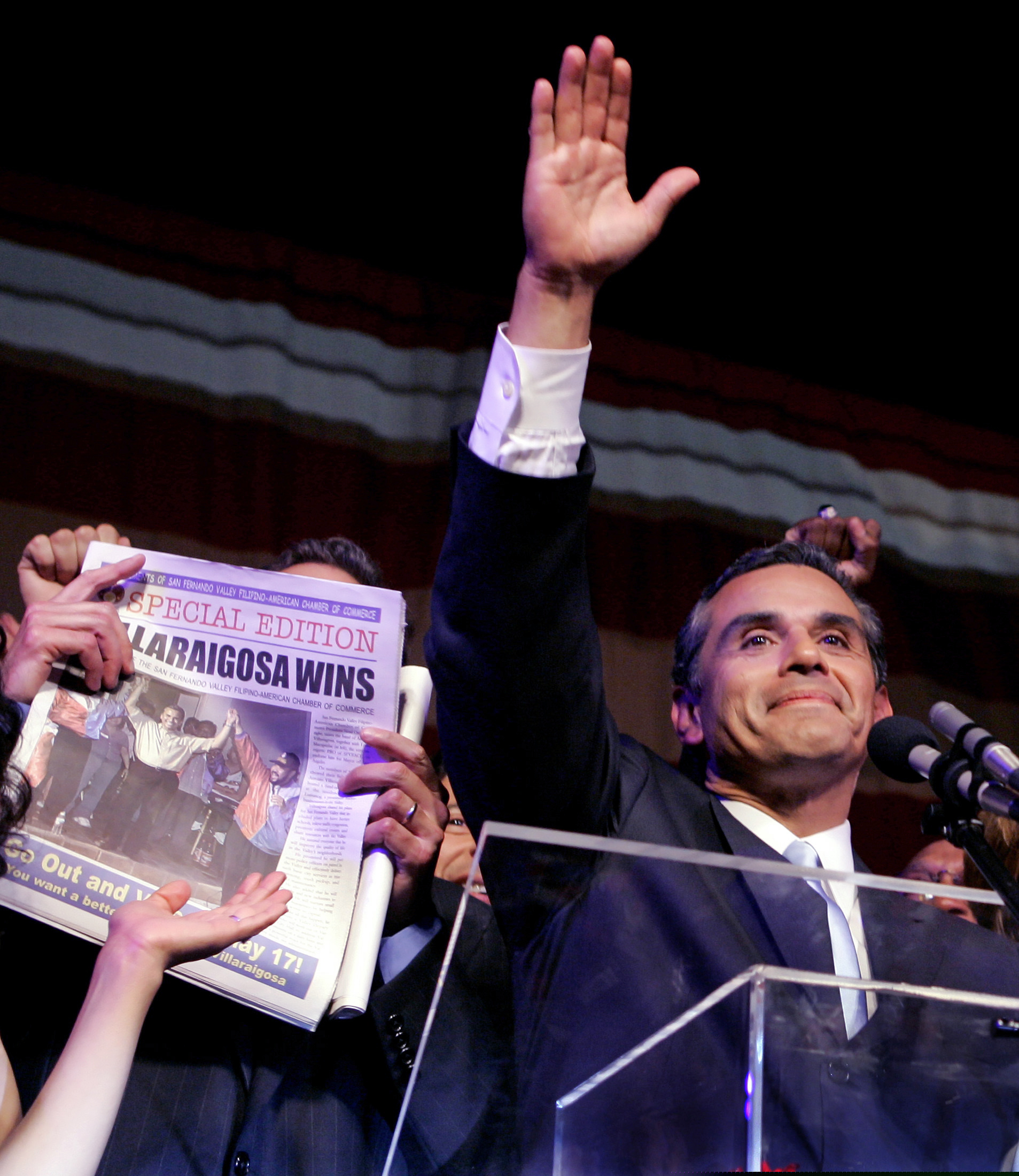

This time, Villaraigosa finished first in both the primary and the run-off elections, and on July 1, 2005, he was sworn in as the 41st Mayor of Los Angeles. Although the city was founded under Spanish rule and, along with the rest of California, was part of Mexico until 1848, Villaraigosa was the first person of Latin American descent to serve as mayor since 1872. His election was widely seen as an affirmation of the growing political power of Latinos, not only in Los Angeles and California, but in the United States as a whole.

As he had in the State Assembly, Villaraigosa took pains to build coalitions across ethnic lines, and increasingly across ideological divides as well. After taking office, he charged head-on at the city’s most intractable challenges, including education and transportation, overcoming entrenched opposition within his own party. Almost immediately on taking office, he persuaded a number of the region’s leaders to drop their opposition to a long-delayed expansion of the city’s subway system.

One of his greatest challenges lay in improving the performance of the city’s schools. He angered many of his old allies in the UTLA by seeking direct mayoral control over failing schools and limitations to teacher tenure rights. Although he failed to gain complete control over the Los Angeles Unified School District, much of which lies outside of the city of Los Angeles, he created a partnership to oversee 22 underperforming schools.

The Mayor faced personal challenges during his first term as well. After 20 years of marriage, Corina and Antonio Villaraigosa divorced in 2007, and some observers wondered whether personal issues would curtail his effectiveness as mayor, and prevent his re-election. The following year saw a major victory for Villaraigosa, when the voters of Los Angeles County passed Measure R, a ballot initiative the Mayor had supported vigorously, raising the sales tax by one-half cent to fund a number of badly needed public transportation projects. The measure enabled the County to invest $40 billion in new rail, road and highway projects. Despite the upheaval in the Mayor’s personal life, he was easily elected to a second term in 2009. Pundits raised the possibility of Villaraigosa running for the governorship of California in 2010, but he quickly affirmed his intention to complete his second term as mayor before seeking any other office.

The financial panic of 2008, and the subsequent deep recession, caused a massive drop in city revenues, requiring deep cuts to municipal services and painful concessions from the Mayor’s former allies in public employees’ unions. In spite of these constraints, Villaraigosa’s second term saw the fulfillment of many of his goals for the city.

The number of schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District meeting the state’s academic performance goals doubled during his time in office. Four new transit lines had opened, and four more were under construction by the end of his second term. Los Angeles became the first big city to synchronize all of its traffic lights, reducing travel time for drivers and eliminating a metric ton of carbon emissions. The Mayor also undertook billion-dollar modernizations of the city’s airport and harbor, and took 2,000 of the harbor’s diesel trucks off the road, reducing emissions by 80 percent. In a city once notorious for its poor air quality, the Villaraigosa administration met the Kyoto Protocol goal for reducing greenhouse gases four years ahead of schedule. By the end of his term, the city was getting 20 percent of its energy from renewable sources. The Mayor made good on a campaign pledge to increase the city’s park space, adding 650 acres of new park land, more than the previous 12 years combined. He also fulfilled his promise to put 1,000 more police officers on the streets, and saw crime drop to its lowest level in 60 years.

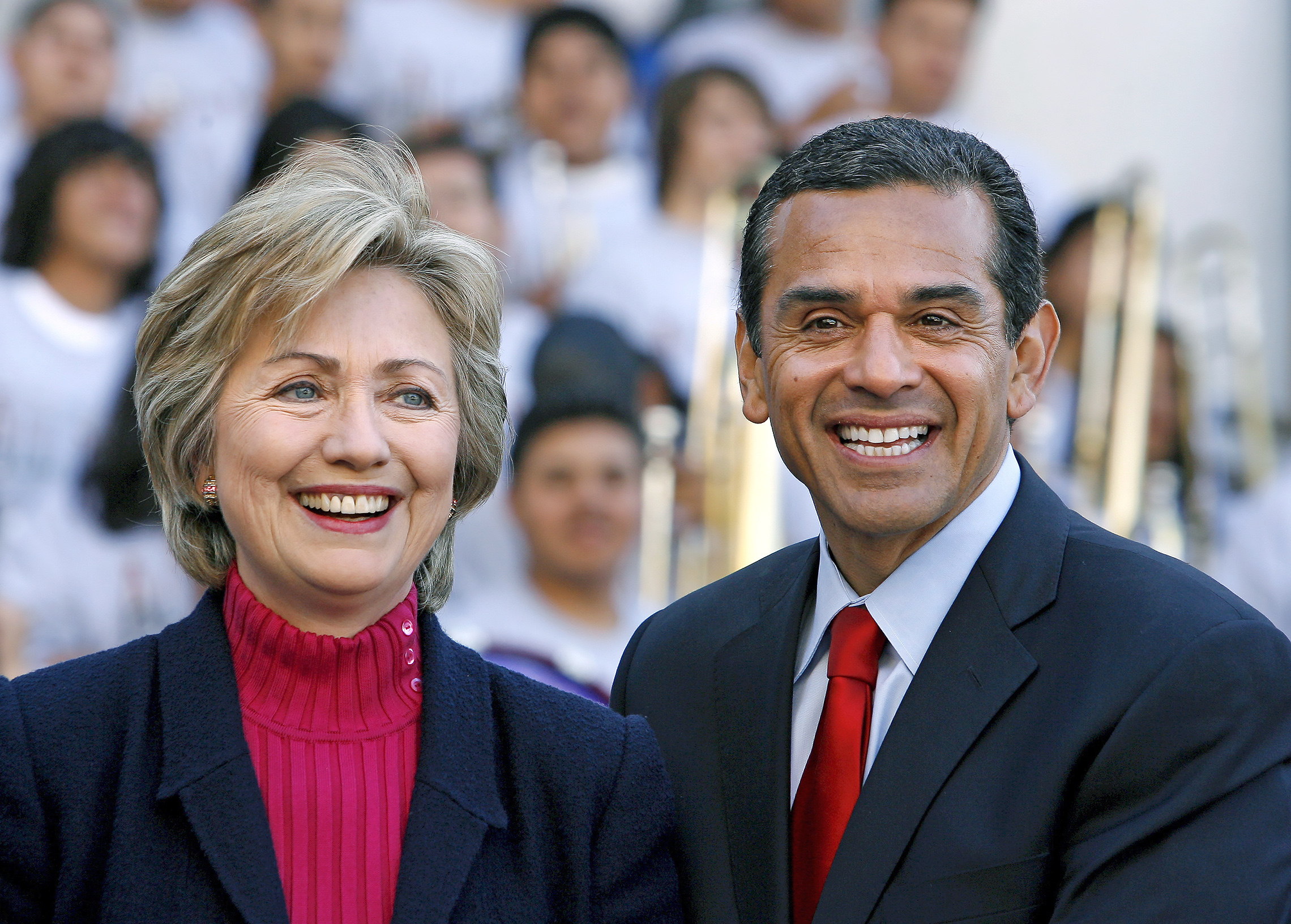

As President of the U.S. Conference of Mayors, Antonio Villaraigosa became a national spokesman for education reform and expanded investment in America’s transportation infrastructure. He received additional national exposure as Chair of the 2012 Democratic National Convention in Charlotte, North Carolina, which re-nominated President Barack Obama and set the stage for the President’s re-election in November.

After completing his second term as mayor in 2013, Villaraigosa worked as a consultant and adviser to Banc of California and the nutritional supplements company Herbalife. In 2016, he married Mexican-born businesswoman Patricia Govea at a ceremony in San Miguel Allende, Mexico. After considering and rejecting a 2016 campaign for the United States Senate, Villaraigosa ran for Governor of California in 2018, finishing third in the state’s “blanket primary” election behind Republican John Cox and the eventual winner, Democrat Gavin Newsom. Later that year, Villaraigosa became co-chairman of the global public strategy firm Mercury.

Whatever his future plans, his impact on the City of Los Angeles has been unmistakable. The transition he championed from reliance on fossil fuels to sustainable energy continues to accelerate. The expansion of the city’s subway and light rail systems, and the turn away from suburban sprawl to a model of increased population density around public transit hubs will remain an enduring hallmark of Antonio Villaraigosa’s leadership.

As Mayor of Los Angeles, Antonio Villaraigosa presided for eight years over the nation’s second largest city, but his life might have turned out very differently. He grew up poor, in a tough neighborhood on the city’s east side. A high school drop-out at 16, he was headed for trouble, but his mother would not give up on him. At her urging, he returned to school, attending night classes to finish his diploma. A sympathetic teacher saw his potential and paid his college entrance examination fees.

At the University of California, Los Angeles, Villaraigosa distinguished himself as a student leader in the civil rights and antiwar movements. As a union organizer, labor leader and Speaker of the California State Assembly, he earned the admiration of allies and adversaries alike with his formidable gift for building consensus across party lines and ethnic divides. In 2005, he was elected Mayor in a historic landslide. The first Latino to lead the city in over 130 years, he won election with support from every community in the most diverse of American cities.

Easily elected to a second term in 2009, he emerged as a dynamic national spokesman for education reform and expanded investment in America’s transportation infrastructure. His administration increased the city’s use of renewable energy, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, improved air quality and saw crime drop to its lowest level in 60 years.

When did you first know that you wanted to go into public service? What piqued your interest in that?

Antonio Villaraigosa: Let me distinguish public service from elected office. I was 15 years old and I was working at a Safeway and there was a boycott, a picket line in front of the Safeway, and it was a picket line and a boycott against the grapes. United Farm Workers were participating in that boycott. And almost from the very beginning — I have never worked in the fields, I didn’t speak any Spanish, I certainly didn’t even totally understand the plight of these workers — but I understood intuitively that I had to participate. And ever since then, as a high school student, and college, really throughout my life, I have been committed to standing up and speaking out for people who don’t have a voice. So I would say I was 15 years old. I never was interested in actually running for office, but I did want to be a change agent. I did want to be part of something bigger than me that empowered people and that made a difference.

Why was that so important to you? What did you see that needed to be changed?

Antonio Villaraigosa: I grew up in a home with a mom who really inculcated in her kids the sense of justice, right and wrong, fairness. This sense of responsibility to family, community, country. And I think early on — and as I said, even at 15 — I felt like where there was an injustice, a wrong, it was incumbent on me to be part of righting it, righting the wrong and searching for justice. So I think it has a lot to do with the upbringing. I grew up in a Catholic home. We believed in social justice, and our mom was very spiritual and very much focused on this responsibility that we all have to our families, as I said, to our communities and to our nation.

What person inspired you most when you were young?

Antonio Villaraigosa: I grew up in a home of domestic violence and alcoholism, and with a mom of just unconditional love and this indomitable spirit to overcome. And she gave all of her kids — all four of her kids, but the three that I grew up with — she gave us this really sense of self, this strong character that we all have, this belief in the possible. She always emphasized education. She would say to us things like, “Maybe you’re poor, but nobody can take away your education. Education is very, very important.” So my mom was, without question, the most important influence in my life and the person who I owe the greatest debt of gratitude to. There are a lot of people who have come in my life that I have looked to and look up to, but nobody has had the influence on my life that my mom has.

You spoke of education and how important that was to your mother. Were there any teachers who inspired you, or played a big role in your life?

Antonio Villaraigosa: The other person, the stranger if you will, that I talk about all the time and particularly since I’ve first ran for office — I was asked by someone, “Who was an inspiration in your life?” just as you are asking me now — and of course I started with my mom, and they said, “Yeah, okay, but what about a stranger? Someone else?” And that someone else is Herman Katz. Herman Katz was my teacher at Roosevelt High School. Now let me backtrack for a moment. I went to Catholic school for most of my life. When my mom couldn’t afford it, we went to public school. I tell people it was a Catholic school that gave me a foundation, but I was kicked out of high school. I led the walkouts at high school, and I got in a lot of fights and was kind of on a road, a bit lost. So I got kicked out of Catholic school and I went to public school. And even though I was getting college prep classes and scored fairly high on academic tests, back in the 1960s they put you in shop classes.

Going to public school, they put me in shop classes and basic reading classes and basic ed classes. And I dropped out. And then I decided to go back, and I met a teacher who I was taking a basic reading class with, and he realized that I had a little more on the ball than that. And he asked me to take a test, and he said, “You’re probably not going to do real well on the test, but I want you to take it anyway.” And I guess I aced it or something. And the rest was something I have chronicled over the years, and that was a guy who just pushed me to take the SAT, offered to drive me to take it because I registered late and I was going to have to take it at another school and my car was broken. Wanted to pay for it when I made excuses about I didn’t have the money. When I got a fairly high verbal score, wanted me to go to college and just pushed me, pushed me, pushed me. And I have always told the story of Herman Katz, because this was a stranger who didn’t know me, but saw something in me and really pushed me to excel. And when I met him, finally, when I was running for office some 23 years after graduating, he didn’t remember me. And I always tell people he didn’t remember me because he helped so many people. I was just one of many that he just set a high bar for and really pushed. So Herman Katz is someone who is still around, and I talk to him from time to time, and he is still an inspiration. Because — a little different than my mom, we know your mom would be your inspiration — this was a stranger, a teacher who dedicated his life to making other lives better. And Herman Katz is his name.