We all need respect. Everybody wants respect of some kind.

Aretha Franklin was born in Memphis Tennessee, but at an early age, her family moved, first to Buffalo, New York, and finally to Detroit, Michigan, where she spent her formative years. Although Aretha Franklin spent much of her adult life in New York and Los Angeles, she would always regard Detroit as her hometown and returned to the city for the last three decades of her life.

Aretha’s mother died when she was ten, and she was raised by her father, a Baptist minister. For 33 years, Rev. C. L. Franklin was pastor of New Bethel Baptist Church in Detroit. Rev. Franklin was not only a popular pastor but an influential civil rights activist, in demand for speaking engagements around the country. Several of his sermons were recorded and issued as phonograph records. Admirers called him the “man with the million-dollar voice.” Notable figures from the civil rights movement were regular visitors to New Bethel Church and were welcome guests in the Franklin home. The country’s premier gospel singers — Mahalia Jackson and Clara Ward — as well as secular jazz and blues musicians, also paid calls on Rev. Franklin, Aretha, and her brothers and sisters.

Aretha’s father encouraged her to sing. When she was very small, her father would stand her on a chair to be seen from the pews when she sang in church. She learned to play piano by ear, although she resisted formal lessons, and by age ten, she could foresee a career as a gospel singer. In her teens, she joined the junior choir that traveled with her father on his speaking engagements. While in California, the Franklins met the young Sam Cooke, lead singer with the gospel group the Soul Stirrers; they followed his career with interest as he left the Soul Stirrers to focus instead on secular pop music. Sam Cooke’s success made a deep impression on young Aretha, who began to wonder if she too might pursue a music career outside of the church.

Her teenage years were difficult; while still a teenager, she gave birth to two sons by different boyfriends. Her grandmother and older sisters helped raise the children while Aretha continued to work at her music. With Rev. Franklin acting as manager, she recorded some gospel songs for a local record label, but her father felt she could do better with a larger national record company.

Passing on an offer from Berry Gordy’s Motown Records in Detroit, Rev. Franklin prevailed on musician friends to form a small group to make a demonstration recording for Columbia Records. An executive at Columbia, the legendary producer John Hammond, was impressed with Aretha’s demos and invited her to New York for a live audition. Hammond and his colleagues were sold, and at age 18, Aretha Franklin was signed to a contract with the most prestigious of American record companies. Leaving her daughters with her family in Detroit, she moved to New York City to make her first major-label recordings.

Hammond teamed Aretha Franklin with some of the best arrangers and musicians in the business and recorded a variety of material, emphasizing the breadth of her talent. Her early sessions included some blues and gospel-tinged numbers, but for the most part, Columbia seemed to see Franklin as a jazz and pop vocalist in the mode of Dinah Washington. Her first single for Columbia, “Today I Sing the Blues,” placed in the Top Ten on Billboard magazine’s Rhythm and Blues (R&B) bestseller chart in 1960. In January, Columbia released her first album, Aretha: With The Ray Bryant Combo. Her first single on Billboard’s pop music Top 40 chart was a 1920s standard, “Rock-a-bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody.”

In 1961, Franklin married Ted White, a friend from Detroit who became her manager. Her records were well reviewed, and she swiftly acquired a reputation in the industry as a compelling new voice. Shy and unassuming by nature, Franklin worked with the veteran African American dancer and choreographer Charles “Cholly” Atkins to acquire a more forceful stage presence. By the mid-‘60s, she was winning an enthusiastic following for her live performances, and critics had begun to call her the “Queen of Soul,” a title that would never be challenged.

Despite her popularity with critics and audiences, Franklin’s record label seemed uncertain about which direction to take her career. Columbia had her recording both R&B and “easy listening” pop songs. She scored hits on both the R&B and Easy Listening charts, but with the new sounds of rock and soul music dominating the charts, Franklin did not believe Columbia was providing the best opportunity to fulfill her true potential.

Determined to make a change, in 1967, Franklin moved from Columbia to Atlantic Records, the R&B-oriented label founded by Ahmet Ertegun. Ertegun, the son of a Turkish diplomat, had spent his student years in Washington, D.C., where he fell in love with jazz, blues, and the entire rich tradition of African American music. He had focused on bringing black artists to the attention of a larger public, enjoying particular success with singer and pianist Ray Charles.

Ertegun assigned producer Jerry Wexler to work with Franklin. Rather than selecting material for her, Wexler urged her to choose her own songs. Rather than having elaborate orchestral arrangements written for her, he urged her to accompany herself on the piano and create the groove for each song, allowing improvising musicians to follow her lead. Her first single for Atlantic, “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You),” shot to number one on the R&B chart, and to number one on the Billboard Hot 100, and gave the title to her first album. In December of 1967, the B-side of her first single, “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man,” also made the R&B Top 40.

The following spring, Atlantic released the single that will forever be inextricably associated with Aretha Franklin. The soul singer Otis Redding had originally written and recorded the song “Respect” in 1965. Franklin rearranged the song, adding the break in which she spelled out the word “R-E-S-P-E-C-T” while her sisters rapidly sang the words “sock it to me,” a popular catchphrase of the day. The new arrangement, her performance — and the unmistakable significance of a woman rather than a man demanding respect from her loved one — spoke to the pent-up frustrations of men and women around the world. The song was embraced as an anthem by both the civil rights movement and by the burgeoning women’s movement.

“Respect” brought Franklin two Grammy Awards, for Best R&B Record and Best Female R&B Performance. Her first Atlantic album became a gold record, selling half a million copies. Franklin scored two more Top Ten singles in 1968: “Baby I Love You” and the unforgettable “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman,” which was written by Carole King. The following year, she released two Top Ten albums, Lady Soul and Aretha Now! The year also saw some of her most successful singles, “Chain of Fools,” “Ain’t No Way,” “Think,” and “Say a Little Prayer.”

In February 1968, she was presented with the Drum Beat Award of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whom she had known since she was a teenager. When Dr. King was murdered in April, Franklin performed the spiritual “My Precious Lord” at his funeral. Now an international star, she toured Europe that spring and was featured on the cover of TIME magazine.

Franklin divorced husband Ted White in 1969 and took full charge of her career for the first time. In the early 1970s, she continued her run of hit albums with Spirit in the Dark and Young, Gifted and Black. She was the first soul artist to play at the San Francisco rock venue Fillmore West, a performance documented on the album Aretha Live at Fillmore West, in 1971. Returning to her roots in gospel music, she recorded a live album at New Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles. Amazing Grace sold over two million copies, making it the bestselling album of her career and the bestselling gospel album of all time.

Jerry Wexler’s departure from Atlantic left her without a strong partner at the label. A collaboration with Quincy Jones on the album Hey Now Hey was a disappointment. She scored her last R&B hit of the ‘70s with “Something He Can Feel” from the soundtrack of the film Sparkle. Her last albums for Atlantic sold poorly, and in the middle of the decade, her career was faltering.

Franklin moved from New York to Los Angeles in search of renewed inspiration and opportunity. In 1978, she married actor Glynn Turman, making a new home for her children as well as his. Family matters took center stage in 1979. In Detroit, Rev. C. L. Franklin was shot at his home, presumably by a burglar attempting a robbery. He survived the shooting but fell into a coma. His children provided 24-hour nursing care at home. Her father lingered in a coma for five years and never regained consciousness.

Franklin ended her 12-year relationship with Atlantic Records in 1979 and began looking for a new label. She was back in the public eye with a memorable performance in the highly successful film The Blues Brothers, singing her 1960s hit “Think.” She signed with Arista Records, run by proven hitmaker Clive Davis. Franklin gradually returned to the top of the charts with her albums for Arista, scoring a gold record with her 1982 album, Jump to It. The same year, Franklin separated from her husband, Glynn Turman, and returned home to Detroit to be near her family. With her brother and sisters at her side, she saw her father through his last days. C. L. Franklin died in 1984.

For Aretha Franklin, personal loss coincided with renewed career success. Her 1985 Arista album, Who’s Zoomin’ Who, was certified platinum and included the massive hit single “Freeway of Love.” The same year, she became the first woman to be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. In 1987, she recorded another gospel album, One Lord, One Faith, One Baptism, at her father’s old church in Detroit. She enjoyed further chart success throughout the 1990s with the singles “A Deeper Love,” “Willing to Forgive,” and “A Rose Is Still a Rose.” The album of the same name was also a gold record. The music industry honored her with a Grammy Legend Award in 1991 and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1994.

In 1998, Franklin was scheduled to appear at the Grammy Awards. When fellow guest performer, the famed operatic tenor Luciano Pavarotti, was forced by illness to cancel at the last minute, Franklin was asked to fill in his place in the program. The orchestra had prepared to accompany Pavarotti in one of his signature pieces, the aria “Nessun Dorma” from Puccini’s opera Turandot. Franklin already had sung the aria herself at a benefit concert a few months earlier, in her own key. To the amazement of producers, musicians, and the audience, she offered to sing it with the orchestra in the tenor’s original key. Her astonishing performance stopped the show. The aria became a regular part of her concert repertoire and inspired her to further explore classical vocal literature. In 2003, after 20 years with Arista Records, she recorded her last album with the label, Jewels in the Crown: All-Star Duets with the Queen.

More than a beloved entertainer, Aretha Franklin had become a treasured living symbol of the American spirit. In 2005, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush. She was no stranger to public ceremonies, having performed at President Bill Clinton’s inaugural gala in 1993. An even more emotional moment occurred when she performed in the frigid open air at the inauguration of President Barack Obama in 2009, delivering a memorable performance of “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee.”

Her 2014 album, Aretha Franklin Sings the Great Diva Classics, included not only her version of “Nessun Dorma” but a version of “Rolling in the Deep,” previously a hit for the British singer Adele. Franklin’s version became her 100th song to make the Billboard R&B/Hip-Hop chart. She had now received every conceivable honor from her peers in the music world, in addition to her 18 Grammy Awards.

After canceling some concerts due to health issues, she toured the United States again in 2014. In 2015, she sang “Nessun Dorma” for Pope Francis at the World Meeting of Families. At that year’s Kennedy Center Honors, during a tribute to Carole King, Franklin sang “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” to an audience including President Barack Obama and Mrs. Obama, winning a standing ovation from the audience and moving the president to tears.

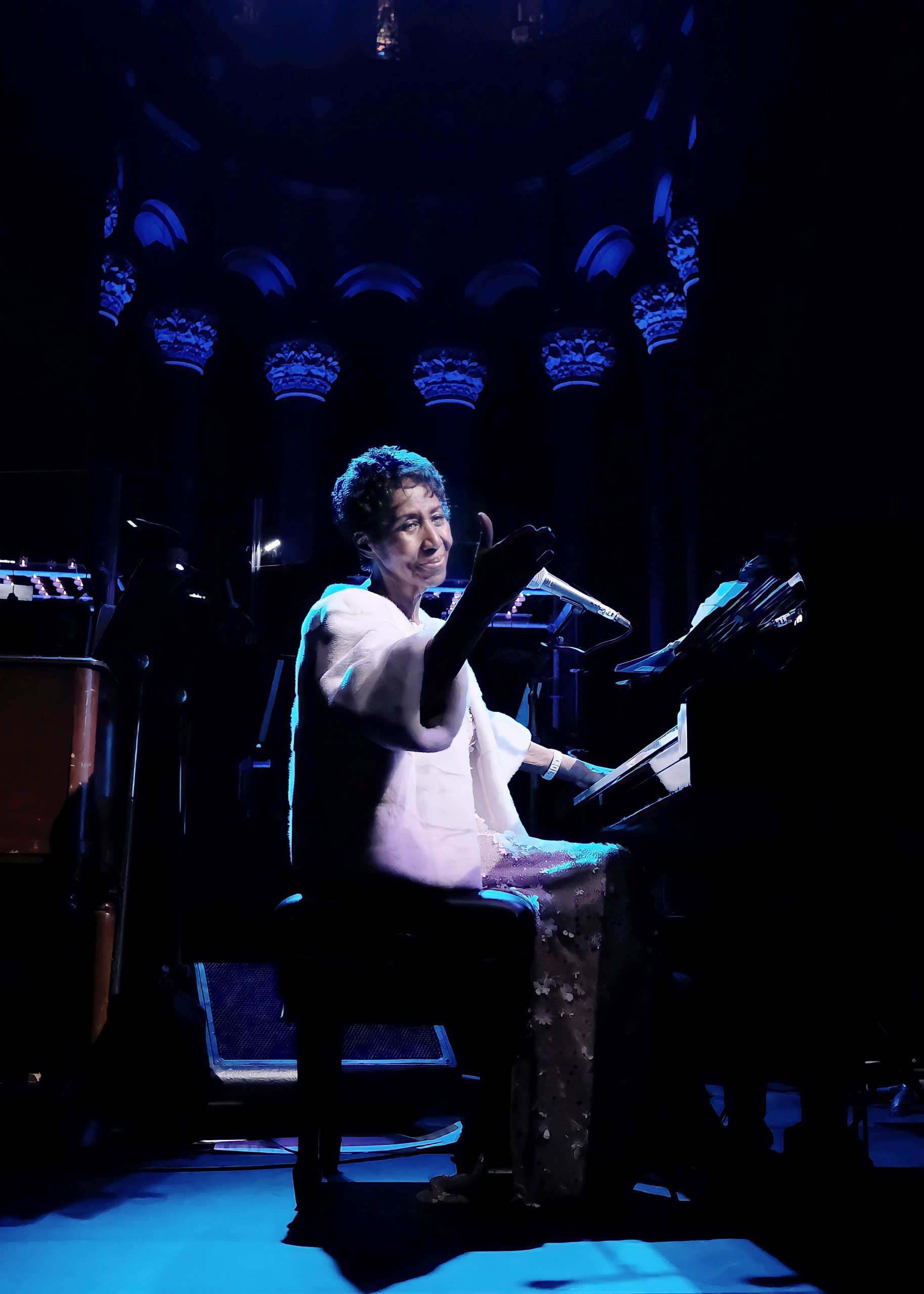

On November 7, 2017, she gave her last public performance, singing at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City, at the 15th Annual Elton John AIDS Foundation Gala. Aretha Franklin succumbed to pancreatic cancer at the age of 76 in 2018. She was mourned around the world. Speakers at her funeral included former President Barack Obama, who said her life and work “helped define the American experience.” Her recorded legacy and the example of her passion, endurance, and commitment to her art continue to inspire musicians, music lovers and ordinary men and women the world over.

On September 15, 2021, Rolling Stone released its list of the “500 Greatest Songs of All Time,” and Aretha Franklin’s “Respect” topped the list as the No. 1 song. The outlet said the 1967 hit “catalyzed rock & roll, gospel, and blues to create the model for soul music that artists still look to today…Just as important, the song’s unapologetic demands resonated powerfully with the civil rights movement and emergent feminist revolution, fitting for an artist who donated to the Black Panther Party and sang at the funeral of Martin Luther King Jr.”

In the late 1960s, the world came to know and love Aretha Franklin as the “Queen of Soul Music.” Her hit recording “Respect” became an anthem of the civil rights struggle and of the nascent women’s movement.

As a child, she sang gospel at the Detroit, Michigan church of her pastor father; with his encouragement, she pursued a career as a professional singer, signing with Columbia Records at age 18. A move to Atlantic Records in 1967 led to a series of hit singles — “Think,” “Chain of Fools,” and “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” — that defined the changing consciousness of the era.

Aretha Franklin continued to record hit albums for the next 30 years, expanding her repertoire to encompass a vast spectrum of music — blues, gospel, R&B, jazz standards, and operatic arias. She was honored by her peers with 18 Grammy Awards and by her country with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

You were born in Memphis. What was that like?

Aretha Franklin: I don’t know what Memphis was like because I was so small when I left there; I don’t even remember being there. I don’t know. It’s a very tiny place, what I saw when I went back to the home where I was born. I can’t say I grew up there because we went to Buffalo from there, I guess when I was maybe about two or three, maybe. I’m not sure.

How did you come to move from Memphis to Buffalo?

Aretha Franklin: My father moved the family to Buffalo, New York. He pastored the Friendship Baptist Church there for about four years. After that, we moved to Detroit and he pastored the New Bethel Baptist Church for about 28 years.

Did your father encourage your singing?

Aretha Franklin: Oh, sure. My dad always encouraged me to sing. Many times, I was too small to be singing, so they would put a chair there, and I would just stand on top of the chair top and sing at the Sunday night broadcast or the Sunday morning services.

So you started singing in the church?

I sang in the junior choir. And I was one of the lead vocalists for the choir. I played piano for the choir occasionally. And customarily on the road when my father would go on the road and have services in major auditoriums and arenas across the country, I would precede him singing, then he would minister from there.

Did you have formal lessons on the piano?

Aretha Franklin: Yes and no.

Aretha Franklin: I started out playing by ear, and my dad wanted me to take lessons, and I didn’t want to take lessons, so I would run and hide every time the teacher came — hide in the closet behind the coats — and once I thought she was gone, I would come out. But I wish today that I had taken the lessons. Now I plan to go to Juilliard sometime soon and hopefully do at least a couple of years there. So I really wish that I had learned the fundamentals then.

When did you start to think about singing outside the church, as a career?

Aretha Franklin: I don’t know. I think maybe about 15 or 16. Something like that.

I had the occasion to meet Sam Cooke, who came to one of our gospel presentations after church that we would have regularly on Sunday evenings. And after meeting Sam and listening to him, he left the gospel field and began to record for SAR, S-A-R, Records. That was Sam Alexander and S. R. Crain, who was one of the Soul Stirrers, and he also was Sam’s manager. Sam had such great success in leaving gospel, or certainly broadening his horizons, I wondered if I could do the same thing. I wondered if I could be as successful singing secular music as gospel. So I talked to my dad about it. And he said, “If that’s what you want to do, by all means.”

Can you tell us about the journey from singing with the church choir to becoming a secular entertainer?

Aretha Franklin: Well, there was a lot of rehearsal involved, certainly. Many hours spent rehearsing, learning the lyrics, and so on. Presentation. Cholly Atkins, who just passed about two weeks ago (in 2003), was my very first choreographer. And pretty much, coming up, it was choreography, lyrics, and selection.

Tell us about the first record you made.

Aretha Franklin: The first record I made for Columbia was “Today I Sing the Blues,” but before that…

Aretha Franklin: I recorded for Chess Records, with whom my dad was affiliated, and in concert out in the Oakland Arena in California. We had services there. My very first recording really was “Precious Lord” (Part 1 and Part 2). After that, there were a few things for the Chess label prior to Columbia. And Columbia, in 1962 — I was brought to the company by John Hammond. I did an audition for Mr. Hammond in a little, small room, just a little larger than this one, with a piano; and my manager at the time, Joe King, who took me over to Columbia; my dad, who put a rhythm section together for me, people that he knew. As he and Art Tatum were very good friends, he would always go and see Art Tatum when he would come in town, and Art Tatum would come to church when he would come to town and have dinner at our home or something like that. But anyway, he knew some of the musicians, so he put a saxophone player — and he called his friend; he asked him to put the rest of the musicians together. He knew the bass player, but he didn’t know anyone else. So anyway, the bass player, Mule Holley — who was rather prominent in those days — put the rhythm section together actually.

You were in Detroit while Motown was getting started. We understand that Berry Gordy, the founder of Motown, was interested in signing you, but your dad turned him down. Is that right?

Aretha Franklin: He went and he visited Berry (Gordy). He went to see Berry, and they met, and they talked. He didn’t feel that Berry had the kind of distribution that he wanted for me. He wanted me to have national and international distribution, and at that time, Berry was just a fledgling label really. He was not “the” Berry Gordy that we know today. Columbia was suggested to him, and it was to my dad’s liking, much better — Columbia — because they had national and international distribution and promo.

You’re lucky to have a father who was so…

Aretha Franklin: Savvy.

So involved and so supportive.

Aretha Franklin: Yes, that’s right.

How did you feel about it at that time? Did you trust him to take care of you and take over your career?

Aretha Franklin: My dad didn’t take over my career. He was just the guiding light to New York. He saw to it that I had the right management and agents and so on before he went back to Detroit.

When did you start writing songs? Was that when you got to New York?

Aretha Franklin: “Without the One You Love” was one of my first compositions. Bob Mersey at the time — who also did some things for Streisand — was on Columbia. We were both on Columbia at the same time. And Mersey arranged that. I walked in the studio that evening and the string players were there. I’d never had strings or anything on any of my records. And just to hear my music being played like that, I just broke down in tears.

How long were you with Columbia?

Aretha Franklin: I was with Columbia for six years before I went to Atlantic Records and signed with Jerry Wexler and Ahmet Ertegun.

That was a big leap.

Aretha Franklin: Yes. That was a quantum leap from Columbia.

What was the difference?

Aretha Franklin: At Columbia, everything pretty much was arranged for me by Mr. Hammond. He would secure the musicians and arrangers — Bob Mersey, who was just magnificent in those days. He probably still is. Clyde Otis did some of the production work in the early days. Ray Bryant did some of the production work, a fabulous pianist. But the difference — I think the main difference was Jerry (Wexler) asked me to sit at the piano and bring in some things, where, at Columbia, they pretty much were telling me what to do rather than just letting me do. So I think that was the main difference. I made the selections once we got to Atlantic.

You went for kind of a new sound, didn’t you?

Aretha Franklin: Well, it was there all the time. We just hadn’t done it.

Could you tell that you were breaking through at that point?

Aretha Franklin: Not really. Not until I heard “Respect” was on the charts, and it was very close to the top of the charts. Then we kind of knew something was happening.

When you recorded “Respect,” did you ever imagine people would be listening to it and loving it all these years later?

Aretha Franklin: You never know. You never know until you put it out there, and the people tell you whether they like it or not, whether you have something or not. It’s standing up pretty good. It’s standing up. That’s what Jerry used to say. We would record, and sometimes we would be in there for maybe four or five hours, but the proof of the pudding for him was the next day. If it stood up and it sounded as good the next day as it did the night before, then he felt like we had something.

The thing about that song is not just the greatness of the performance, it became kind an anthem for different movements in our society.

Aretha Franklin: Well, we all need respect. Everybody wants respect of some kind.

How did you feel when you saw that picked up that way?

Aretha Franklin: I thought it was fabulous. “Hey, go ahead!”

Can you remember how you felt when you won your first Grammy?

Aretha Franklin: First Grammy? I was not there. I wasn’t even aware of what the Grammy meant. Jerry Wexler and Arif (Mardin) and Ahmet (Ertegun) were there, picking up the Grammys. I didn’t know what Grammys were for maybe the first couple of years, one or two years, and then somebody went, “Hey, you won a Grammy!” “I did? Okay. And a Grammy is what?” Well, I found out what Grammys were, and what they meant, and I’m very, very proud of the fact that I have a record number of them.

You stayed with Atlantic and Jerry Wexler for a long time. Was that unusual?

Aretha Franklin: I don’t think so. I don’t argue with success. I was there from ‘67 through ‘79. That’s 13 years. I think Ray Charles was with the label longer than that. It’s not very long.

What made that such a successful relationship?

Aretha Franklin: We were just compatible and had mutual respect, I think, for each other.

Do you ever have stage fright?

Aretha Franklin: In the early years, yes. After time, I became more confident about it. You learn a lot as you go

Did you have any tricks to try to get over it?

Aretha Franklin: No. I am a trickless artiste.

You mentioned going to Juilliard to get some more training. What do you want to do with that?

Aretha Franklin: Teach. Teach and coach. I’d really like to teach a master class in soul at Juilliard, yes.

We’ve all loved hearing you sing Puccini’s “Nessun dorma.” Are there other operatic arias or classical songs you’d like to sing?

Aretha Franklin: “Nessun dorma,” yes. I love that. That’s one of my favorites, and yes, I love Puccini. “Song to the Moon” (Dvořák) and some other arias that I’m learning, “Doretta’s Aria,” and “O mio babbino caro” — things like that.

There are people who say you are the greatest singer of all time. Do you agree with that?

Aretha Franklin: I’ll leave that to other people. It’s not for me to say. But as far as singers are concerned, some of the singers that I particularly like would be Barbara Hendricks — classical — and Kathleen Battle, and Leontyne Price, of course. And I think that Judy Garland was one of the world’s great singers as well.

Have you ever recorded “Somewhere Over the Rainbow?”

Aretha Franklin: I have. In fact, it was on one of my first recordings at Columbia.

Well, thank you very much for your time.

Aretha Franklin: Thank you.

What a pleasure talking to you.

Aretha Franklin: My pleasure. Thank you very much.