America is a great place. From the days of my not being able to enjoy the luxuries of a country club, I now own the club and I do enjoy it. And I'm very pleased and I feel very privileged that this country has given people like myself the opportunity to do the things that I've been able to do.

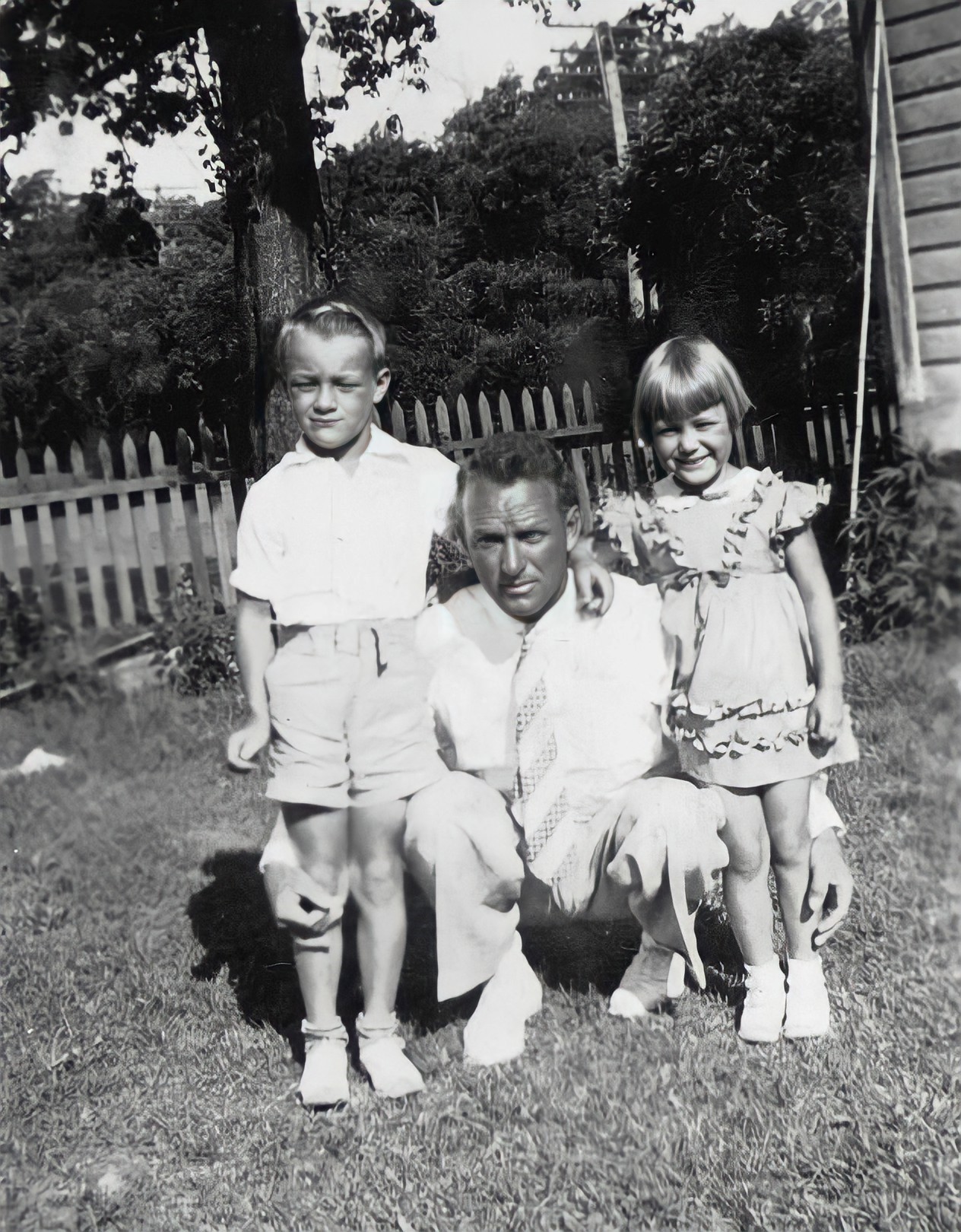

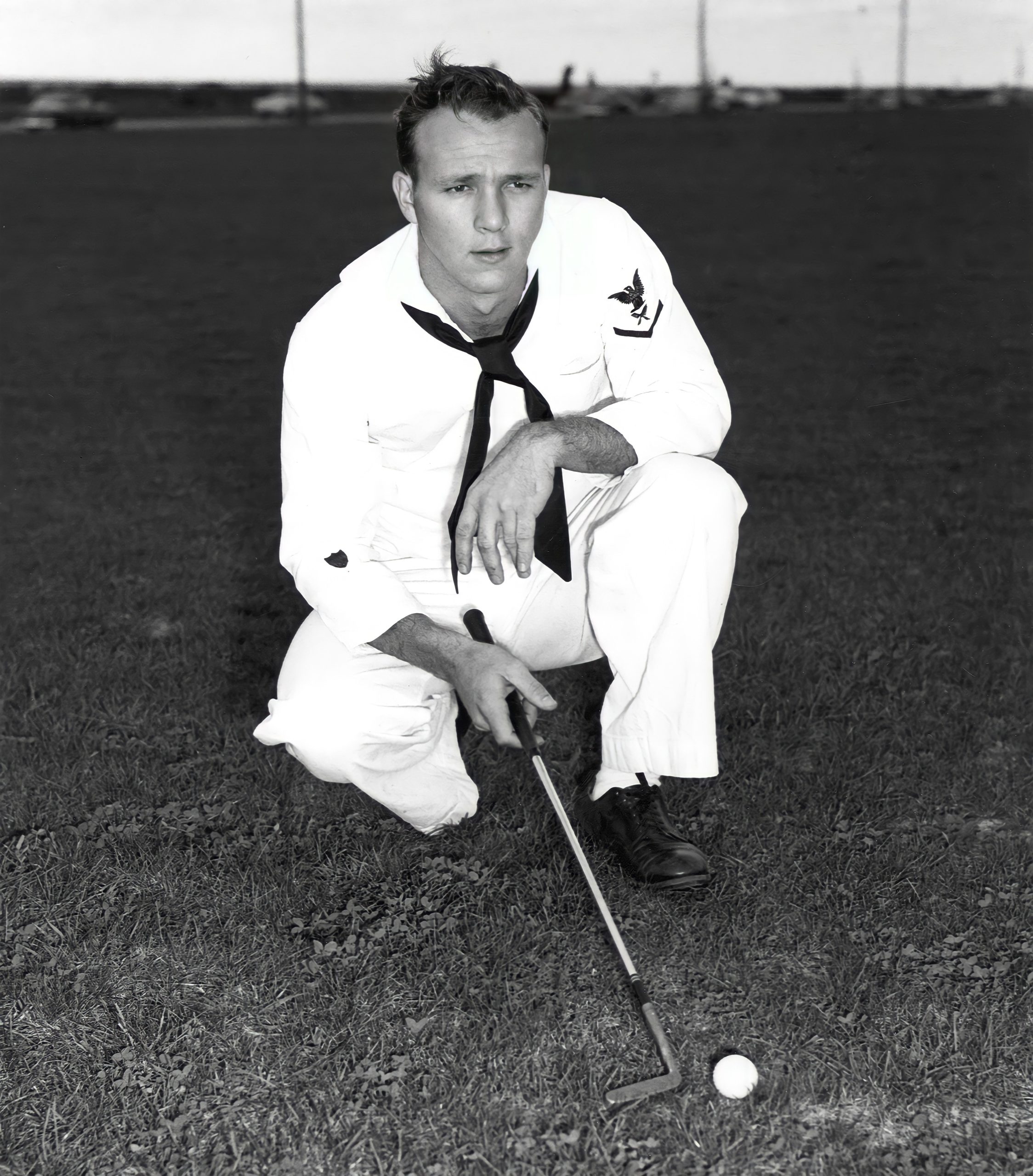

Arnold Palmer was born in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, a steel-producing town in Western Pennsylvania. His father worked as a greenskeeper at the Latrobe Country Club; the family lived at the edge of the golf course. An enthusiast of the game, the elder Palmer eventually became the club pro. He began teaching young Arnold the rudiments of golf as soon as the boy could hold a short-handled club. Arnold Palmer showed a precocious talent for the game, winning the Western Pennsylvania Junior three times and the Western Pennsylvania Amateur championship five times. He attended Wake Forest College on a golf scholarship, but left after three years to enlist in the Coast Guard. In 1954 he won the U.S. national amateur championship in Detroit, and began to plan a professional career. The same year, he met and married Winifred Walzer. Their marriage would last until her death 45 years later.

In his first season as a professional, 1955, he won the Canadian Open. Television was presenting golf to a mass audience for the first time. Palmer’s good looks, winning personality and aggressive style of play made him the game’s first television star. He solidified his position as a major figure in the sport with his victory in the 1958 Masters Tournament.

For decades, horse racing, boxing and baseball had enjoyed the loyalty of mass audiences in the United States, while golf had labored under its reputation as a rich man’s game. In Arnold Palmer the game found a star with appeal to average Americans, and participation in the sport at all levels soared.

In 1960, Palmer formed a partnership with attorney Mark McCormack. The pair had met playing golf in college. McCormack was starting a sports agency, and Palmer became his first client. Together, Palmer and McCormack pioneered new strategies in sports marketing. McCormack’s firm became International Management Group, the world’s leading sports agency.

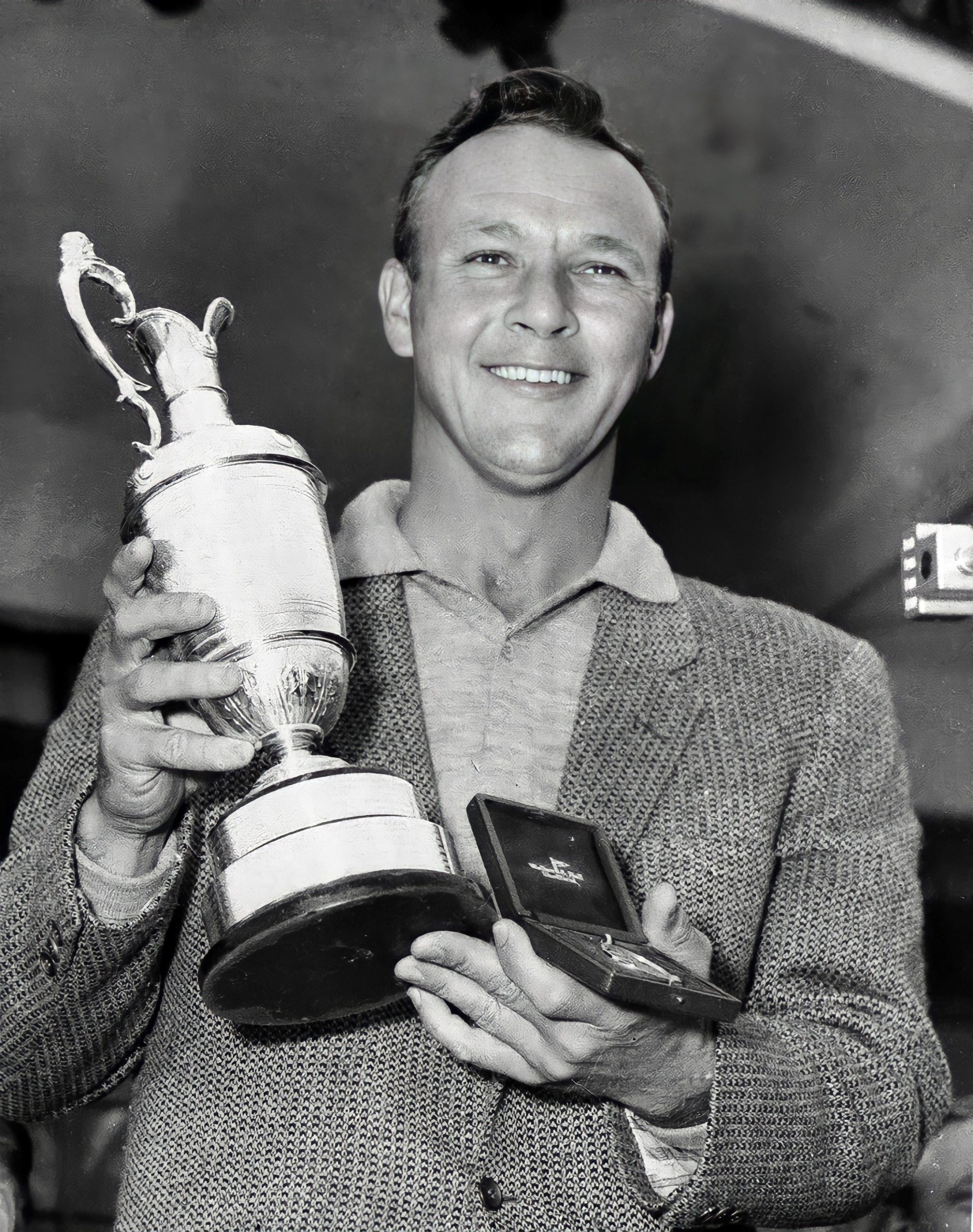

The 1960 season was a decisive one for Palmer. Having won the Masters and the U.S. Open, he came within a single shot of winning the British Open. He was named Sportsman of the Year by Sports Illustrated magazine. His appearances on the tour now attracted a large following that sports writers dubbed “Arnie’s Army.”

Palmer returned to the British Open the following year and triumphed. In 1962 he won the Masters again and scored a second victory in the British Open. From 1960 to 1963 he won 29 titles in national or international competitions. In 1964, he won the first World Match Play competition and won the Masters for a fourth time. His earnings in prizes now exceeded those of any professional golfer prior to that time. In 1967, as in three previous seasons (1961, ’62 and ’64) he won the Vardon Trophy, for lowest scoring average in PGA events. That year, he became the first professional golfer to earn $1 million from the game.

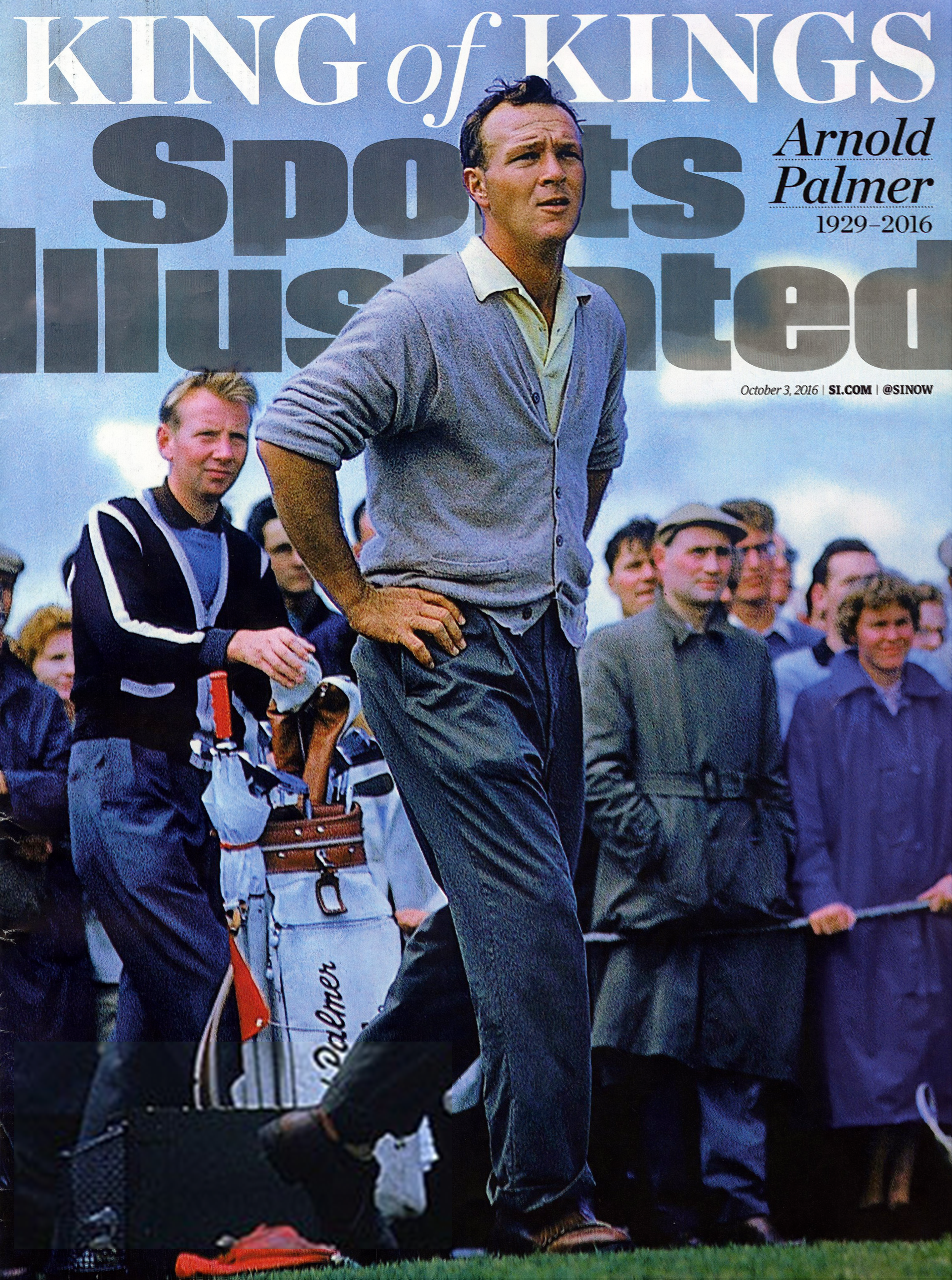

Arnold Palmer won a PGA Tour event every season from 1955 to 1971. He played on the U.S. Ryder Cup team six times from 1961 to 1973, winning more than 22 Ryder Cup matches and leading Team USA to two victories as Captain. He was named “Athlete of the Decade” for the 1960s in the Associated Press poll. Over the course of his professional playing career, he won 92 championships in national and international competition, 62 of them on the PGA Tour.

Arnold Palmer’s endorsements and investments in golf-related businesses made him one of the highest earners in the game long after he stopped winning tournaments. One endorsement, in particular, brought him special satisfaction. In 1971 he bought the Latrobe Country Club, where he had first learned the game. He was a part owner of the Pebble Beach Resort in California; he also owned the Bay Hill Club and Lodge in Orlando, Florida, where he hosted the Arnold Palmer Invitational. For the rest of his life, he lived in Latrobe in spring and summer, wintering in Orlando, Florida, which he helped turn into a golfers’ mecca.

In the early 1970s, Palmer negotiated a deal to build the first golf course in China. Palmer himself became a member of the American Society of Golf Course Architects. He founded the Arnold Palmer Design Company, which has built more than 300 golf courses in 25 countries on five continents.

Early in his international career, Arnold Palmer took up flying, often traveling from tournament to tournament in his own plane. He graduated from prop planes to jets in 1966, and in 1976 set a speed record for one class of jets flying around the globe.

Arnold Palmer was a member of the inaugural class of the Golf Hall of Fame in 1974. He participated in the first Senior PGA Tour (now known as PGA Tour Champions) in 1980, winning ten events, including five senior majors. Having done so much to popularize golf as a spectator sport in the early days of television, in 1995 he helped found a new channel dedicated entirely to the sport, and served as founding chairman of the Golf Channel.

In 1998, Palmer received the PGA Lifetime Achievement Award. The same year, at age 70, Arnold Palmer underwent surgery for prostate cancer. He soon returned to active play on the Senior Tour, and used his celebrity to raise awareness of the disease and its treatment. The following year, Winifred Palmer died at age 65, after 45 years of marriage. The Women and Children’s Hospital in Orlando is named for her.

Arnold Palmer’s contributions to the communities where he lived have been recognized in the names of Arnold Palmer Regional Airport in Latrobe and Arnold Palmer Boulevard in Orlando. His name is spoken every day by thousands of Americans in another context. He popularized the combination of iced tea and lemonade which is called by his name in bars and restaurants all over the United States.

Arnold Palmer competed in the Masters Tournament for the 50th and final time in 2004, although he would continue to appear as an honorary starter for the rest of his life. In 2005, Palmer married Kathleen Gawthrop, and the following year he retired from all-tournament golf.

Over the course of his career, Arnold Palmer published a number of books on golf and several volumes of memoirs, the last of which summed up his story in its title, A Life Well Played. He died in Pittsburgh, at age 87, while awaiting heart surgery. His ashes were scattered at Latrobe Country Club, where he spent so much of his childhood, and first learned the game that made him famous, and that he did so much to foster.

In the second half of the 20th century the game of golf experienced a worldwide boom in popularity. Once considered an elite sport played by ladies and gentlemen of leisure, it has since become a pastime embraced by men and women of all backgrounds. No one person did more to democratize and popularize the sport than Arnold Palmer.

Born to a working class family in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, Arnold Palmer learned the game from his father, the greenskeeper at the local country club. Blessed with natural physical gifts, enormous dedication and undeniable passion for the game, Palmer developed a devastating drive and became the dominant golfer of his era. In a six-year winning streak, he won the U.S. Open once, the British Open twice, and the Masters Tournament four times. In all he recorded 92 victories as a professional, 62 of them on the PGA tour.

Palmer’s rise coincided with the arrival of television in a majority of American homes. His easygoing, unpretentious personality and daring approach to the game endeared him to television audiences from coast to coast. His personal popularity is often credited with a dramatic increase in the popularity of golf as both spectator sport and recreation.

His achievements won recognition by the sporting press as Sports Illustrated’s Sportsman of the Year and the Associated Press’s Sportsman of the Decade in the 1960s, by his peers with the Lifetime Achievement Award of the Professional Golfers Association, and by his government with the Congressional Gold Medal and the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Could you tell us about the early days in Pennsylvania, and your dad and how he affected your life?

Arnold Palmer: I think we have to start with the fact that I was born in 1929, that’s a long time ago. And most people don’t even remember what happened in 1929 or 1930. But if you think about the Depression, and life being raised in the Depression was considerably different than we recognize things today. My father was a young man who had been afflicted with polio, or infantile paralysis, and he was handicapped to a degree by having his left leg and ankle affected by the disease. And as a result, he developed his upper body, and to the point where he was about as strong as anyone I had ever seen, from his waist up. And that had an influence on me and my future. He also started at age 16 working on a golf course as a laborer. That also had an effect on my life. And what, of course, we know it today as my life. But he was a very determined person, and that job that he got at 16 on the golf course led to his entire life and his future. He went from working on the golf course as a laborer building the golf course, to the superintendent, or as we knew it in those days, the greenskeeper. And all of this was happening in the early ’30s. And having been just born, I was a part of all that. And I can remember being babysat by the crew on the grounds who were working for my father, taking care of a nine-hole golf course in Latrobe, Pennsylvania.

You say it had a direct impact on his life, but obviously on yours as well. Is it fair to say your father believed in discipline?

Arnold Palmer: It’s very fair to say. He was a man that was grateful for the job he had during the Depression. And we, of course, living on the edge of the golf course, did a lot of things that you wouldn’t think about today as having happened on the edge of a golf course. We raised chickens, we picked the eggs. We had pigs, which we butchered in the fall. And all of these things were a part of my early life and had a definite influence on me. And the fact that we were living right on the edge of the golf course.

I can recall back as early as 1935, when the ladies would play golf and my father and his discipline wouldn’t allow me on the golf course. So I used to lie on the sixth tee, and some of the ladies used to come by, and they got to know me and know who I was. And one day one of the ladies said, “Arnie, if you drive my ball across the ditch, which was about 125 yards from the tee, I’ll give you a nickel.” Well in 1935, two or three nickels would get a movie and an ice cream cone, and I was aware of that. So I took the lady’s club and I drove the ball across the ditch for her and I got my nickel.

Is that the first money you earned on the golf course?

Arnold Palmer: I guess you could say that, yes.

You grew up around the course, but you weren’t able to play at the club. It was a different set of circumstances for you than those that played the club.

Arnold Palmer: As we know country clubs today, it was out of bounds, so to speak. My father in the early days only went into the club himself on business. And of course, as far as my being at the club, that was out of the question. And the only time I was even allowed on the golf course was with my parents, or on caddie’s day. And I played golf in the summer on caddie’s day. And occasionally when my mother would take me out in the evenings after the golf course was virtually deserted, and I would play with her. I didn’t even get to play very much with my father, who I longed to be able to get out and play with him, ’cause he could hit the ball and he was a pretty good player. But as you say, it was different. The country club atmosphere was certainly there, but it wasn’t something that I was permitted to enjoy at my early age.

Was that something you thought you wanted to someday accomplish? Was that something you aspired to do and to become?

Arnold Palmer: There’s no question about the fact that I wanted to be able to swim in the swimming pool with the other kids, and I wanted to be able to go into the clubhouse like the other kids could, but I wasn’t allowed to. I suppose the only satisfaction that came from some of the things that happened in those days was that when I went swimming, I swam in the stream that ran by the golf course, and I got to use the water before the members got to use it. They pumped the water from that stream into the swimming pool. But that was sort of an inside thing with us, and we did get a kick out of it. But as I say, and as you had said, my father was a disciplinarian. And he considered it a privilege that he was able to work at the club. And as far as the privileges of the club, that was off-bounds for us.

Now you own that club, so if you want to swim in the pool, you can.

Arnold Palmer: America is a great place. And from the days of my not being able to enjoy the luxuries of a country club, I now own the club and I do enjoy it. And I’m very pleased and I feel very privileged that this country has given people like myself the opportunity to do the things that I’ve been able to do. I think that could define the American Dream for anyone. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a country club, or steel mill, or whatever it might be. The opportunity to go from the lowest position in the steel mill, the golf course, the business, whether it be an accounting firm, or a law firm, or whatever it is, that you can go from that position to the head of that firm, or to the head of the club, or to own the club, or the steel mill, or whatever it might be is, as they say — and as I’ve heard many times from some of my ethnic friends — it can only happen in America.

Is there anyone else that you can think of growing up that served as a real role model for you or an inspiration?

Arnold Palmer: My father was my major teacher, disciplinarian. But my mother lent a lot to me and to my life, in that, when things weren’t going right, or when my father was too tough, I had the soft feel of my mother to help me, and she did. And she a lot of the times gave me confidence that I needed to overcome some of the things that happened that weren’t so pleasant.

It was good to have the hard and the soft, that’s what makes us who we are.

Arnold Palmer: I think that’s what I’m saying. I had both sides. My father and I became very, very close friends, not just father and son, but friends. And when there was a problem, my mother was able to kind of smooth that problem out.

Were there any books that you read along the way that inspired you?

Arnold Palmer: When I got a little older and got interested very much in the game of golf, I followed (Bobby) Jones’s life and read a lot about him. And I also studied the Byron Nelson book. When he was the pro at Inverness in Toledo, he went through a program of self-teaching, and I read that thoroughly. And of course, I thought that Byron Nelson, from a golfing standpoint, was one of the finest players that ever lived.

Talk about your final amateur match in 1954. Was that a turning point in your life?

Arnold Palmer: You could say that was the turning point in my life, the final match of the U.S. Amateur. There was more than just that match that was the turning point in my life.

I played Bob Sweeney, who was the jet-set type, if you wish. He was the European who came to America and played golf in the winter, and back to Europe in the summer. And I suppose that you could say that here is the ultimate in golfing living. But he was also a fine man and a great player. And I was awed by him, even when I was playing him in the finals of the Amateur. And of course, to beat him was probably one of the great moments of my life. And that, along with what happened in the next month after that, really set up the turning point in my life. One being National Amateur Champion, playing in the Fred Waring Memorial Golf Tournament. Meeting what became my wife a few months later at that tournament. All of that, along with a decision to turn pro was the turning point in my life.

Was that the match where you had a putt that you backed off at the last moment, and you waited to stand over that putt until in your mind you said you knew you were going to make it? Was it that match?

Arnold Palmer: Well, I don’t think that I ever stood over a putt that long. I just said, I knew I was going to make it. But I tried very hard to get very comfortable over a putt that I was nervous about, or I was scared of, if you want to call it that. And I made it. It was more concentration than probably style, or anything else. And again, it worked for me and I was most appreciative of that.

How do you reach a point in your life that you’re confident enough to let yourself relax over the putt that you’re nervous about, and you let yourself accomplish that? How can people do that in their lives?

Arnold Palmer: I don’t think you can ever get over a putt, or a situation in a life where you can just totally relax. Whether it means something as important as the National Amateur Championship, or the U.S. Open, or anything in golf. But I think that you can train yourself to be in situations like that and then when you get in that situation, use the thing that you’ve learned, and that you’ve concentrated on in your practice, or in your make-up to do something. And again, I have to go back to the fact that my father had a tremendous influence on me when those situations arose. And he had never really done those things, but he had a feel for what I was trying to do and instilled in me the ability to rely on the things that he had taught me about the game of golf. And the basic fundamentals of the game. And whether it be a putt, or a drive, or whatever it might be, to be able to call on the things that I had practiced, in the basic fundamentals. And of course, in the positive thoughts in my mind, the concentration that was there. And I feel like those are the things that helped me accomplish what I accomplished.

You leaned on the lessons that your father taught you.

Arnold Palmer: Well, there’s no question about that, I did. And I think that the learning, and being able to call up those situations, or the training that I had, the discipline. I think that in America today we don’t have the discipline that I was brought up to understand as a part of my life. Whether it’s holding a knife and fork properly, or whether it’s using the proper English language, whatever it might have been, those are things that I was most appreciative of. And the fact that sometimes I thought I was being leaned upon a little too hard, or harshly by my father. But after having grown up and experiencing all those things that he taught me and made me understand, I couldn’t be more appreciative. And the only thing that I could be sorry for is that sometimes maybe I can’t transmit that to other people, so that they understand that. And I think that’s all a way of life and what is happening in our way of life today. I don’t think we appreciate what we have, and how to enjoy what we have. And I suppose that, again, one of the things that makes my life so full and so enjoyable is the fact that I went through some times that weren’t quite so enjoyable and they weren’t so easy. And if I could have other people understand it, I think they would enjoy their lives even more.

Do you feel as if some of this was destined to happen?

Arnold Palmer: Destiny? I’m not sure. I think destiny comes with what you want and what your desires are and how much you’re willing to give to create the things that you enjoy. Call it destiny, if you wish.

You can make your own destiny.

Arnold Palmer: That’s kind of what I’m saying.

How did you develop your style on the course?

Arnold Palmer: I was taught to play the game of golf like a game, and to enjoy it as a game. You know the saying, everything isn’t winning, but it is almost. And I leave a little room there for “almost.” Certainly, I didn’t win every event that I played in. And I didn’t win a lot of the times when I wanted to win very badly, but it didn’t end my life. It wasn’t so dramatic that it changed my lifestyle, or my style of living when I lost. And I think that being able to lose and being able to cope with losing was almost as important as winning. And winning was first and foremost, because it was necessary. But losing was as much an education as winning was. And I think the combination of the two is very, very important. And being able to understand that is very important in a person’s life.