Whatever is the scariest is almost always what I end up choosing, because I figure that’s where there’s something to be learned.

Audra McDonald was born in Berlin, Germany, where her father, Stanley McDonald, Jr., was stationed with the U.S. Army. Following his military service, the family settled in Fresno, California. Both of Audra McDonald’s parents were educators. Her father, after serving as a high school teacher and principal, became assistant superintendent of human resources for the Fresno Unified School District. Her mother, Anna McDonald, later became an administrator at California Polytechnic University in San Luis Obispo. Both parents played piano and came from highly musical families.

The older of two daughters, Audra was a rambunctious, hyperactive child. Rather than medicate her, her parents sought an outlet for her prodigious energy. When a local theater group, the Good Company Players, announced the formation of a children’s musical theater group, her parents took her to audition, with her father acting as accompanist. The theater became the center of young Audra’s life. The company’s director, Dan Pessano, taught her the basics of stagecraft and theater etiquette. She became a favorite with local audiences, playing roles such as Dorothy in The Wiz.

On graduating from the performing arts magnet program at Theodore Roosevelt High School, she auditioned for the Juilliard School of Music in New York City. The school has a highly regarded actor training program, but young Audra, who had had little formal voice training, was accepted into the classical voice program. Although her heart was already set on the Broadway theater, she spent the next years singing classical music rather than acting. She eventually chafed at the discipline and took a year off, landing a spot in the chorus of the Broadway musical The Secret Garden. She stayed with the show on its national tour before returning to Juilliard to graduate in 1993.

The following year, she landed her breakthrough role, New England mill worker Carrie Pipperidge in a revival of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s classic Carousel. Even critics who were skeptical about the colorblind casting of the show were enthusiastic about McDonald’s soaring voice and sly comedic skills. In this, her first featured role on the New York Stage, she won Drama Desk and Critics Circle awards, and a Tony Award for Best Perfromance by a Featured Actress in a Musical.

In 1995, McDonald won a role in the play Master Class by Terence McNally. McDonald was cast as a young voice student who survives a grueling lesson with the legendary opera singer Maria Callas, portrayed by the British actress Zöe Caldwell. Although Master Class was a straight dramatic play, rather than a musical, the action required McDonald’s character to sing a notoriously difficult aria from Verdi’s Macbeth — a far cry from the comic numbers she sang in Carousel. Her performance drew universal praise, not only from the drama critics, but from opera lovers drawn to the play’s subject matter. McDonald won a second Tony Award for her performance, this time for Best Performance by a Featured Actress in a Play.

She followed this with her feature film debut in the film Seven Servants. Meanwhile, playwright McNally was at work on a script that would give McDonald her first chance to originate a role in a Broadway musical. In McNally’s musical adaptation of E.L. Doctorow’s novel Ragtime, McDonald played the tragic role of Sarah, a doomed working woman in turn-of-the-20th century New York. The show opened in Toronto, where it ran for a year before transferring to Broadway. Prior to the Broadway opening, the original cast album featuring McDonald was released. The show flourished on Broadway, and once again, McDonald was honored with a Tony Award for Best Performance by a Featured Actress in a Musical.

In 1998, McDonald released her debut recording as a solo artist, Way Back to Paradise, a collection of songs by contemporary composers. The same year, she made her Carnegie Hall debut, a season-opening concert with the San Francisco Symphony, broadcast live on PBS. The following year she starred in an original Broadway musical, Marie Christine, retelling the classical tragedy of Medea against a setting of 19th century New Orleans and Chicago. The show closed in the second month of its run, but McDonald’s performance was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Performance by a Leading Actress in a Musical, her first nomination for a starring performance.

In 1998 and 1999, McDonald appeared in the films The Object of My Affection and The Cradle Will Rock. The year 1999 also marked the beginning of a distinguished television career for McDonald with a leading role in Having Our Say: The Delany Sisters’ First 100 Years. She followed this with appearances in the television remake of the musical Annie, the HBO film of the play Wit, a recurring role in Law and Order: Special Victims Unit, and a regular role in the series Mister Sterling. McDonald made more feature films as well, including It Runs in the Family and The Best Thief in the World. In the year 2000, Audra McDonald married musician Peter Donovan. The couple would have one child.

Audra McDonald returned to Broadway in the 2004 revival of the classic American drama A Raisin the Sun, starring opposite Sean “Diddy” Combs in his Broadway debut. McDonald received a fourth Tony Award for her performance. She assumed her first major Shakespearean role in a New York production of Henry IV in 2004. She made an even more daring leap in 2006, leaving the world of Broadway musicals and drama altogether to make her opera debut at the Houston Grand Opera. In a single evening, she performed Francis Poulenc’s one-woman opera, La voix humaine, and the world premiere of another one-act opera, Send, by Marie Christine composer Michael John LaChiusa. In the same season, she was seen by television audiences in The Bedford Diaries and Kidnapped.

The following year, McDonald appeared at the Los Angeles Opera in Mahagonny by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill. The recording of this production received Grammy Awards for Best Opera Recording and for Best Classical Album. Later in 2007, McDonald starred in the Broadway revival of 110 in the Shade, a lesser-known work of Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt, the team behind the long-running off-Broadway show The Fantasticks. During the run of 110 in the Shade, McDonald received word that her father, an experienced pilot, had died in a flying accident. Following her Broadway run in 110 in the Shade, McDonald moved to Los Angeles to work in movies and television. For the next three seasons, she appeared as Dr. Naomi Bennett in the primetime network series Private Practice. In 2008, she reprised her Tony Award-winning dramatic role in a television film of A Raisin in the Sun. Her marriage to Peter Donovan ended in 2009. She continued to appear in feature films as well, including the 2012 police drama Rampart, with Woody Harrelson.

In 2012, McDonald returned to the Broadway stage for one of the greatest challenges of her career, Bess, in George and Ira Gershwin’s American opera Porgy and Bess. First produced in 1935, Porgy and Bess has been subject to previous reinterpretations and revisions. The 2012 revival, billed as The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess, with a script revised by playwright Suzan Lori-Parks, went further than ever before in reconciling George Gershwin’s operatic ambitions to the limits and freedoms of the Broadway stage. In McDonald’s hands, the role of Bess, often stereotyped as a heartless “loose woman,” emerged as a distinctly injured and uniquely human character. The production was a sensation and earned Audra McDonald a fifth Tony Award, this time for Best Performance by a Leading Actress in a Musical.

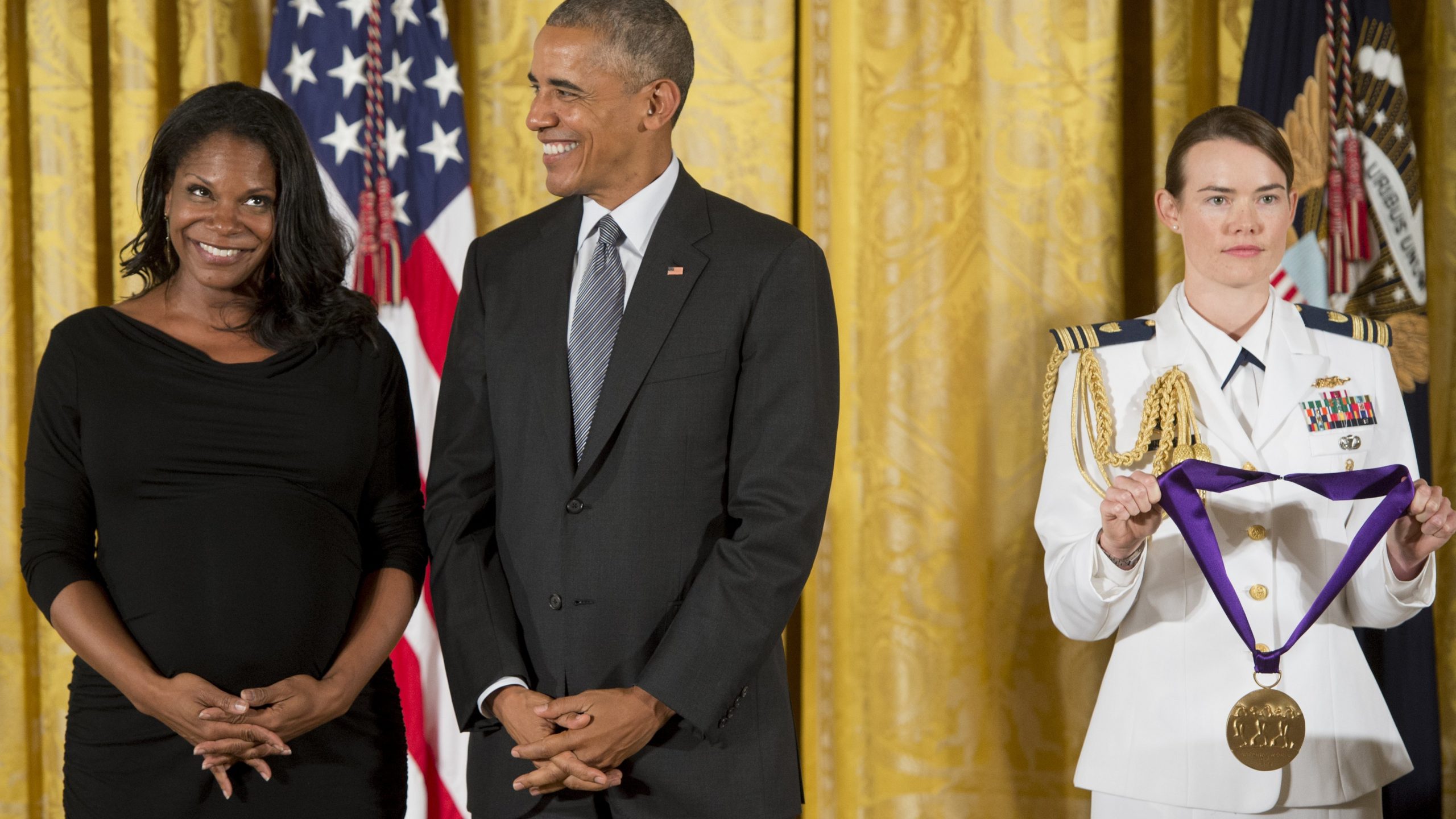

Between starring roles in the theater and on television, Audra McDonald appears in concert with America’s greatest orchestras, and hosts television programs such as the PBS series Live From Lincoln Center. Her bestselling record albums include How Glory Goes and Build a Bridge. In October 2012, she married actor Will Swenson. Their blended family includes their three children from previous marriages. In 2014, Audra McDonald took the role of jazz singer Billie Holliday in a Broadway revival of the play Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill. Once again she received rave reviews and won the year’s Tony Award for Best Actress in a dramatic role. This unprecedented sixth Tony makes her the most honored actress in the history of the award.

Many young girls dream of stardom on the Broadway stage. The few who achieve it share talent, dedication, and a consuming passion for their art, but for one of that rare company to stand out among all the others requires something more. More than a luminous stage presence, more than a luscious voice and impeccable musicianship, Audra McDonald brings to every song and every role, old or new, the deeper insight that finds the human being inside the character, and pierces the heart of all who hear her.

As a little girl in Fresno, California, her parents encouraged her to join a theater group to channel her hyperactive energy. She became a local favorite and went on to study classical singing at New York’s Juilliard School. She made her Broadway debut before graduating, and had won three Tony Awards before the age of 30.

Equally at home in dramas and musicals, she has won six Tonys to date — an all-time record — for her performances in the musicals Carousel, Ragtime, and Porgy and Bess, and in the dramatic plays Master Class, A Raisin in the Sun and Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill. In addition to dominating the Broadway stage, Audra McDonald has made successful forays into grand opera. She enjoys a successful career in film and television, and as a recording artist, and regularly appears in concert with America’s greatest orchestras.

You’ve had such a great career as a musical theater performer. But you’re also a concert artist, a recording artist, and a dramatic actress on stage and films and television. Is there one medium that you prefer? How are they different for you?

Audra McDonald: I think in the end there is one ultimate goal with all of them, and that is, as a performing artist, you want to explore the deepest, most truthful way to express a point of view, or whatever the character is thinking, or whatever emotion you’re trying to convey. I think with the different media it’s just about what muscles you use to express that.

Obviously, if you’re doing something in the theater, what you’re doing has to be on a large enough scale that everybody in the theater can experience it. You have to hit the back wall, as they say. You have to be able to make sure, if you’re experiencing some incredible thing on stage but no one can hear you, then you might as well not be on stage. However, if you were to be that big on television or in film, you’d look grotesque. It would look odd and weird, because the camera is right in your face, so you just have to learn how to exercise different muscles, but still going for the same goal, which is the most truthful way that you can express a character or an emotion. So for me it’s just about staying within that truth, and then learning about the different techniques. And then the same thing with concertizing too. You have no script. You’ve got no fourth wall. There’s nothing, really, no character to hide behind. So for me it was about learning how to communicate with the audience, and be comfortable with who I am is enough, and then slip into character for each song. But in between each song, you have to be honest and be comfortable with who you are. So that was also another sort of thing for me to learn. It’s trial by error. I fell on my face many times, figuratively and literally. I have fallen on my face in concert. But someone said to me once — a lady I was doing my first national tour with, Mary Fogarty. She had done a million plays by this point. She was about 70 years old, she’s passed away now. But I said, “Where did you study acting?” She said, “The stage, honey. I learned on the stage.” I said, “You didn’t go to college? “She said, “No, no, no, no. I had to get on stage to figure out what I was doing wrong, and the stage will teach you.” And I’ve never forgotten that either.

In 2012, you starred in The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess on Broadway. In some ways, this staging was a departure from previous productions of Porgy and Bess. How would you describe it?

Audra McDonald: I’ve seen many productions of Porgy and Bess, and there have been so many different interpretations over the years, even within the few years that George Gershwin was alive, from the time that he first wrote it until the time he passed away, and then again in Ira Gershwin’s lifetime too. Many different permutations. One that everybody talks about is the uncut version that was brought back in the ’70s by Houston Grand Opera and made very popular. How our production differed from that is we cut out a good deal of the repetitive stuff within, like repetitive choruses, or instead of five verses of something we would do maybe three verses of something. And we added a little more dialogue. We weren’t the first ones to do that. That was done right after Gershwin died, when it was brought back to Broadway, the first revival by Cheryl Crawford, with Ira Gershwin’s blessing. He actually did some of the work on that as well.

Because we were doing it on a Broadway stage, we were not doing the big operatic version that you usually see at the Met, or many opera houses across the world. We wanted to make ours a more intimate experience, so we looked at it more like a play or a piece of musical theater than necessarily an opera. I guess that’s the main difference. But I think the other difference is, usually, when you see productions of Porgy and Bess done in an opera house, they’ll do about 15 performances total. We did over 250, 260 performances of that. No, 300! We made it to 300, because we were doing it eight times a week. So there’s a chance to really get into those characters and explore in a way that you might not necessarily get a chance to do. You meet up with a company, you work for a couple of months. You do 15 performances and then everybody goes off to do maybe another version of Porgy and Bess or whatever, but you don’t get that cohesive sort of day in and day out, month in and month out, I think, that we were lucky enough to get with that long, long run.

Did you try to approach anything differently in the character of Bess?

Audra McDonald: My goal in taking the role wasn’t “I’m going to do something completely different than what everyone else has done.” That wasn’t it. For me it was, “I know this piece. I love this piece. I’ve seen it and I’ve memorized it. I want to understand Bess. I want to understand why she makes the choices she makes. What is her history that has led her to these choices?” You don’t just all of a sudden appear somewhere. You’ve got to have history that takes you there. What has happened in her life that has led her to this point? And even with every time I’ve seen the production, I think, “Oh, gosh. Why does she… …he’s so wonderful.” And I think the whole audience thinks that. It’s part of the tragedy of it. Why does she go away at the end? Look at what a great guy Porgy is. Why does she leave that? Why does she succumb? So I really, really wanted to understand. I wanted to get as deep inside her head as I possibly could. So I went back to the original book — because that’s the wellspring, that’s where these characters were first born — to DuBose Heyward. I wanted to see. Because obviously you can’t put everything that’s in the book in an opera.

Fascinatingly enough, a lot of the book is in the opera. DuBose Heyward wrote many more lyrics than I think he’s perhaps credited with. A lot of the lyrics are credited to Ira Gershwin, but if you read it, they’re lifted right out of the book, right into the score. Many, many of the passages.

So I went back to the book, which has a little more detail about Bess, and then I studied women of that era. I studied African American women of that era. I studied cocaine usage. I studied the effect it has on the body. I studied opportunities that would have been available to women of that time if you didn’t have a job or a husband, and you were addicted to drugs. You don’t have many choices nowadays, but certainly not then. And all that helped me just to understand her a little better. I also wanted to get down to the core of her, which for me was she’s an addict. Once I understood this is someone who is an addict, I was able to understand her choices a little better. She goes from being addicted to Crown to being addicted to Porgy, and then gets sucked in by Crown again, and then once Porgy and Crown are both gone, she gets addicted to some sort of comfort again, which is the cocaine. But that addictive personality helped me make more sense of who Bess was. That’s something that probably hadn’t really occurred to me before. Everybody else used to say, “Oh, what. She just loves life. She’s a fast woman, that’s all. She’s just a fast woman who loves life.” Well, that’s not true. That’s surely what she projects, but that’s not what’s going on underneath. And that’s what I wanted to get to, what’s going on underneath.

Does winning awards, like a Tony Award, change your life?

Audra McDonald: Yes and no. I think in other people’s eyes your life changes. You become identified with it. You’re a Tony winner. You’re not just Audra McDonald, you’re a Tony winner, a two-time — whatever — Tony winner. That’s a wonderful thing, and there’s a lot of prestige that comes with that, and the gratitude.

Winning a Tony completely surpassed my dreams. I just wanted to be on Broadway. That’s all I wanted. So winning one Tony, I thought I was done. So what’s happened is just hard for me to fathom. So I don’t think about it all that much. So to answer your question, no. It doesn’t change my life all that much, because I’m still me. I’m still an artist who’s searching, trying to evolve, an artist who — nine times out of ten — is dissatisfied with her work, and beats herself, and goes out there and tries again and again, and falls on her face and looks for new challenges. I think the Tony says, “Okay. Great job. Keep going.” But it doesn’t bring money. Maybe Oscars do, but Tonys do not. Theater doesn’t bring money in general. That’s not why you do it. If you go into theater for money then you’ve really gone into the wrong business. What’s the joke? “I want to tell you how to make a million dollars. Invest $10 million in a show! That’s how you make it.” I never felt any different on the inside. So I guess, no, it didn’t change my life, but outwardly it did. Does that make sense? I don’t know.