There is no such thing as an average human being. If you have a normal brain, you are superior.

Benjamin Carson was born in Detroit, Michigan. His mother, Sonya, had dropped out of school in the third grade, and married when she was only 13. When Benjamin Carson was only eight, his parents divorced, and Mrs. Carson was left to raise Benjamin and his older brother Curtis on her own. She worked at two, sometimes three, jobs at a time to provide for her boys. Benjamin and his brother fell farther and farther behind in school. In fifth grade, Carson was at the bottom of his class. His classmates called him “dummy” and he developed a violent, uncontrollable temper. When Mrs. Carson saw Benjamin’s failing grades, she determined to turn her sons’ lives around. She sharply limited the boys’ television watching and refused to let them outside to play until they had finished their homework each day. She required them to read two library books a week and to give her written reports on their reading even though, with her own poor education, she could barely read what they had written.

Within a few weeks, Carson astonished his classmates by identifying rock samples his teacher had brought to class. He recognized them from one of the books he had read. “It was at that moment that I realized I wasn’t stupid,” he recalled later. Carson continued to amaze his classmates with his newfound knowledge and within a year he was at the top of his class.

The hunger for knowledge had taken hold of him, and he began to read voraciously on all subjects. He determined to become a physician, and he learned to control the violent temper that still threatened his future. After graduating with honors from his high school, he attended Yale University, where he earned a degree in psychology.

From Yale, he went to the Medical School of the University of Michigan, where his interest shifted from psychiatry to neurosurgery. His excellent hand-eye coordination and three-dimensional reasoning skills made him a superior surgeon. After medical school he became a neurosurgery resident at the world-famous Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. At age 32, he became the hospital’s Director of Pediatric Neurosurgery, a position he would hold for the next 29 years.

In 1987, Dr. Carson made medical history with an operation to separate a pair of Siamese twins. The Binder twins were born joined at the back of the head. Operations to separate twins joined in this way had always failed, resulting in the death of one or both of the infants. Carson agreed to undertake the operation. A 70-member surgical team, led by Dr. Carson, worked for 22 hours. At the end, the twins were successfully separated and can now survive independently.

Dr. Carson’s other surgical innovations have included the first intra-uterine procedure to relieve pressure on the brain of a hydrocephalic fetal twin, and a hemispherectomy, in which an infant suffering from uncontrollable seizures has half of its brain removed. This stops the seizures, and the remaining half of the brain actually compensates for the missing hemisphere.

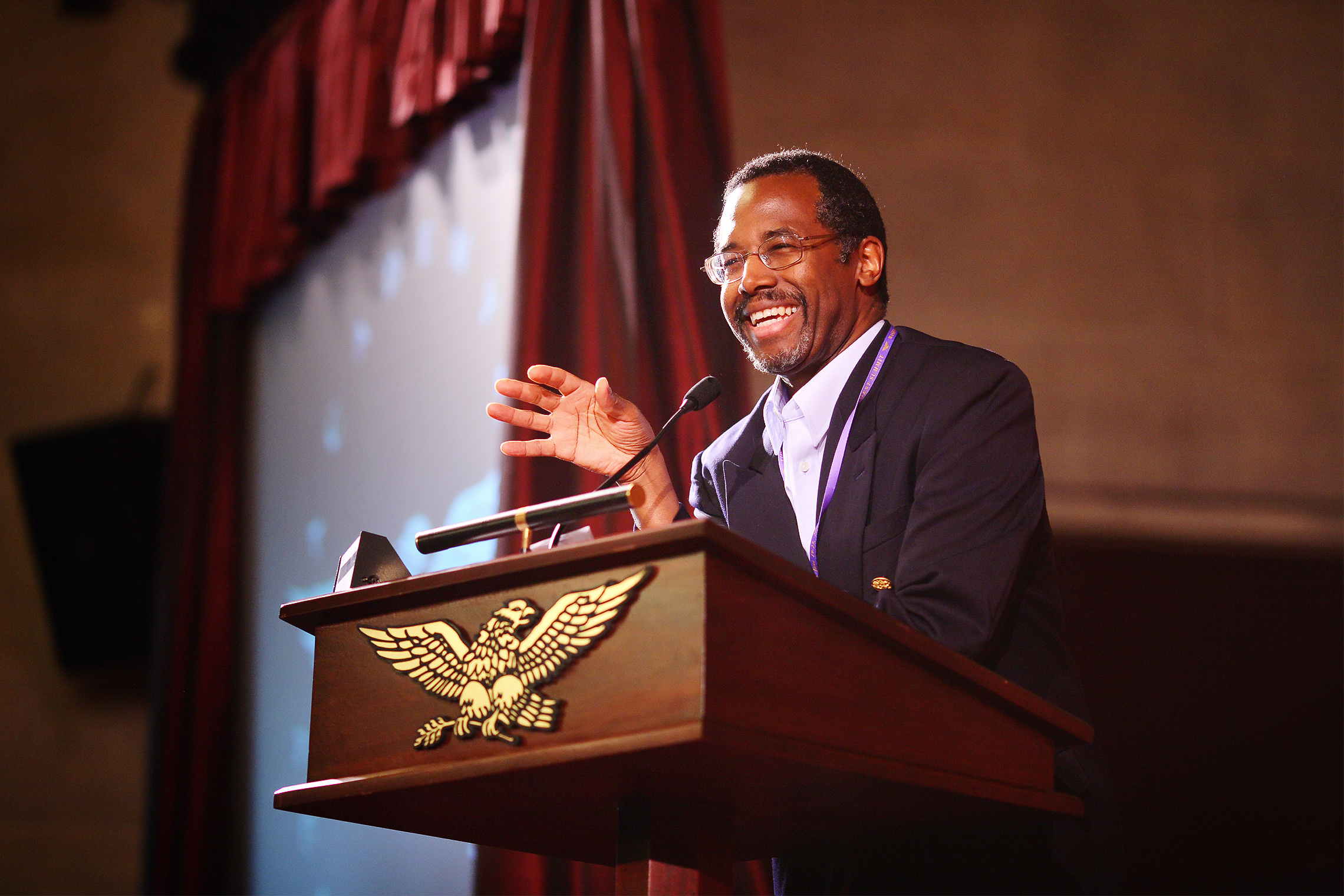

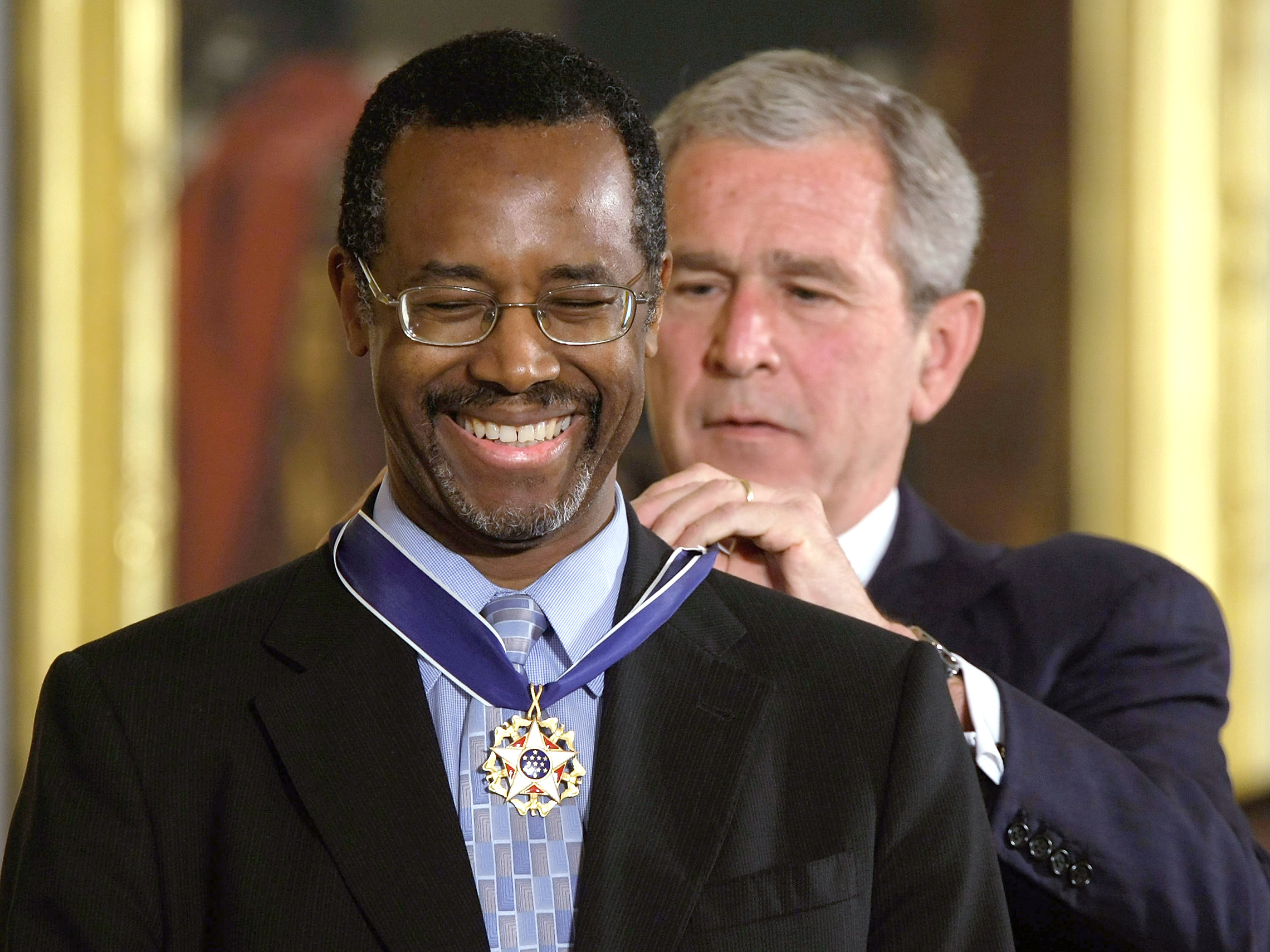

In addition to his medical practice, Dr. Carson has long been in constant demand as a public speaker, and devotes much of his time to meeting with groups of young people. In 2008, President George W. Bush awarded Dr. Carson the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Dr. Carson’s books include a memoir, Gifted Hands, and a motivational book, Think Big. Carson says the letters of “Think Big” stand for the following:

Talent: Our Creator has endowed all of us not just with the ability to sing, dance or throw a ball, but with intellectual talent. Start getting in touch with that part of you that is intellectual and develop that, and think of careers that will allow you to use that.

Honesty: If you lead a clean and honest life, you don’t put skeletons in the closet. If you put skeletons in the closet, they definitely will come back just when you don’t want to see them and ruin your life.

Insight: It comes from people who have already gone where you’re trying to go. Learn from their triumphs and their mistakes.

Nice: If you’re nice to people, then once they get over the suspicion of why you’re being nice, they will be nice to you.

Knowledge: It makes you into a more valuable person. The more knowledge you have, the more people need you. It’s an interesting phenomenon, but when people need you, they pay you, so you’ll be okay in life.

Books: They are the mechanism for obtaining knowledge, as opposed to television.

In-Depth Learning: Learn for the sake of knowledge and understanding, rather than for the sake of impressing people or taking a test.

God: Never get too big for Him.

Dr. Carson opposed passage of the federal Affordable Care Act of 2010, often called the ACA or Obamacare. After retiring from his position as Director of Pediatric Neurosurgery at Hopkins in 2012, Carson began to speak more frequently on other public issues and emerged as a vocal critic of the Obama administration. In the news media and political circles, he attracted considerable attention as a possible candidate for public office and retired entirely from medical practice in 2013.

In May 2015, Dr. Carson ended several months of speculation by announcing his intention to seek the Republican Party’s nomination for President of the United States. He led the polls for a brief period preceding the Iowa Caucus, but after a disappointing showing in that contest and early primaries, he suspended his campaign and endorsed former rival Donald Trump for the Republican nomination.

Following Trump’s election in 2016, the President-elect nominated Dr. Carson to join his cabinet as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. Although Dr. Carson had no previous experience serving in government, the Senate confirmed his appointment in March 2017, and Dr. Carson assumed leadership of the federal department charged with combating urban decay and assisting America’s renters and homeowners.

In 2021, Dr. Carson founded the American Cornerstone Institute (ACI), a conservative think tank centered around advancing policies that promote “faith, liberty, community, and life.”

“There is no such thing as an average human being. If you have a normal brain, you are superior. There’s almost nothing that you can’t do.”

When Benjamin Carson was in fifth grade, he was considered the “dummy” of his class. His classmates and teachers took it for granted that Ben would take an entire quiz without getting a single question right. He had a temper so violent that he would attack other children, even his mother, at the slightest provocation. “I was most likely to end up in jail, reform school, or the grave,” he remembers.

But Benjamin Carson turned his life around. He graduated from high school with honors, went on to Yale University and to medical school. At age 32, he became Director of Pediatric Neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. He is internationally recognized as a pioneer in his field. In his operation on the Binder Siamese twins in 1987, he succeeded where all predecessors had failed, in separating twins joined at the head.

Through his books and lectures, Dr. Carson eagerly shares the story of his success with young people. In his own words: “You do have the possibility of controlling your own destiny if you are willing to put in the appropriate amount of time and effort.” Or, as he tells young people everywhere, “Think Big.”

President Donald Trump named him to his cabinet following the 2016 election, and in 2017 Benjamin Carson became the nation’s 17th Secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

(Dr. Benjamin S. Carson was interviewed twice by the Academy of Achievement — on June 29, 1996, at the Achievement Summit in Sun Valley, Idaho, and on June 7, 2002, at the Summit in Dublin, Ireland. The following transcript draws on both interviews.)

People often speak of brain surgery as the epitome of something difficult and hard to achieve. When did you first have a notion that you actually wanted to do this?

Benjamin Carson: Medicine has always been the only career that I considered, but the aspect of medicine changed. It went from missionary doctor to psychiatrist and then I toyed for a while with the idea of being a cardiovascular surgeon. But, as I began in medical school — toward the end of my first year — to realize that I really didn’t want to do psychiatry, and I felt that although cardiothoracic surgery was challenging, that it didn’t offer me enough variety of cases. And then I said, “Well, what’s an area where you could become an authority very quickly?” and I said, “The brain, because nobody knows anything about the brain.” And I spent all those years thinking I was going to be a psychiatrist. So, I already knew quite a lot about the brain. So, it was toward the end of my first year in medical school that I decided that neurosurgery was going to be the right field for me.

You say you never really considered anything other than medicine. You must have been a very serious student, to get into medical school.

Benjamin Carson: I was not a serious student at all. In fact, I was a horrible student. But, you know, like many students, I kind of envisioned myself as a doctor anyway, despite the fact that I wasn’t doing well. I can remember we used to sit in the hallways at Detroit City Hospital or Boston City Hospital for hours and hours because we were on medical assistance, which meant we had to wait until one of the interns or residents was free to see us, and I didn’t mind at all because I was in the hospital. And, I was listening to the PA system. “Dr. Jones, Dr. Jones to the emergency room,” just sounded so fabulous. And I would be saying, “They’re going to be saying ‘Dr. Carson’ one day.” But, of course we have beepers now. But nevertheless, it was just wonderful to have that dream and to imagine myself in that setting.

It was perhaps unrealistic, because…

We lived in the inner city, single parent home, dire poverty, my mother only had a third grade education. I was perhaps the worst student you’ve ever seen. I thought I was really stupid. All my classmates and teachers agreed, and my nickname was “Dummy.” But fortunately I continued to hold onto that dream and, you know, when I was in the fifth grade, my mother put us on this reading program and said we had to read two books a piece from the Detroit Public Library and submit to her written book reports, which she couldn’t read, but we didn’t know that, and she’d put a little check mark on them and act like she was reading them.

So she actually could not read.

Benjamin Carson: She couldn’t read, no. She only had a third grade education, but she was horrified when she saw my report card at mid-term in the fifth grade. I was failing almost every subject. She knew what a difficult life she had, having only a third grade education, trying to raise two young sons in the inner city, with no resources. She saw me heading down the same path, and my brother as well. She just didn’t know what to do. She prayed for wisdom and came up with this idea of turning off the television set and letting us watch only two to three pre-selected TV programs during the week. I was considerably less than enthusiastic about this program, as you might imagine.

We had to stay in the house and read these books, and our friends were outside and they were playing and they knew we couldn’t come out. It seems like they would be making just that much more noise to torment us. I hated it for the first several weeks, but then all of a sudden, I started to enjoy it because we had no money, but between the covers of those books, I could go anyplace, I could be anybody, I could do anything. And I began to learn how to use my imagination more because it doesn’t really require a lot of imagination to watch television, but it does to read. You’ve got to take those letters and make them into words, and those words into sentences, and those sentences into concepts, and the more you do that, the more vivid your imagination becomes. And, I believe that’s probably one of the reasons that you see that creative people tend to be readers, because they’re exercising their mind.

A lot of people say, “I can learn everything I need to know. I can watch this video or I can watch this DVD,” or what have you, but that’s like saying you can develop your muscles by watching somebody else lift weights. You have to actually exercise your mind in order to get it to be active and to get it to be creative, and reading is a tremendous way to do that.

I was reading about people in laboratories, pouring chemicals from a beaker into a flask and watching the steam rise, and completing electrical circuits, and discovering galaxies, and looking at microcosms in the microscope, and I just acquired so much knowledge, and I had put myself into those settings, and I saw myself differently than everybody else in my environment who just wanted to get out of school so they could get some cool clothes and a cool car. And, I was looking down the pike and seeing myself as a scientist or a physician or something of that nature, and that was one of the things that sort of carried me through much of the ridicule and some of the hardships that a person would have to go through coming from my environment and going to medical school.

We’ve also read that you had to overcome a terrible temper.

Benjamin Carson: I had an incredibly horrible temper. I was one of those people who thought they had a lot of rights, and of course, the more rights you think you have, the more likely someone is to infringe upon them. And I did get into fights, I would injure people. I tried to hit my mother in the head with a hammer. I would just become irrational because I would get so angry. It all culminated one day when —

Another youngster angered me, and I had a large camping knife, and I tried to stab him in the abdomen, and fortunately he had on a large metal belt buckle under his clothing, and the knife blade struck with such force that it broke and he fled in terror. But, I was more terrified as I recognized that I was trying to kill somebody over nothing. This was after I had turned my grades around. I was an A student at that time, but I realized at that moment that with a temper like that, my options were three: reform school, jail or the grave. None of the options appealed to me. So, I just locked myself up in the bathroom and I started praying, and I said, “Lord, I can’t deal with this temper.” And, I picked up my Bible and I started reading from the Book of Proverbs. That was the first day that I started doing it, and I’ve been doing it every day since then because it had all these verses in it about anger, and it seemed like they were all applicable to me. And, while I was there, I had a revelation and that revelation was that the reason I was always angry is because I was always in the center of the equation. So, just step out of the center of the equation and then everything won’t be directed at you, and then you won’t be angry, and also, you’ll be able to look at things from other people’s points of view. Also, where I lived, you know, it was sort of like a macho thing. You get angry, you kick down the wall and punch in the window and it makes you into a big man. But, I came to understand that when you react like that, it actually is a sign of weakness because it means that other people and the environment can control you, and I decided that I didn’t want to be that easily controlled. And, I’ve never had another problem with temper since that day.

There were so many verses in the Book of Proverbs about anger. If you get an angry man out of trouble you’re just going to wind up doing it again, because anger is always going to have him in trouble. And “A man who can control his temper is mightier than a man who can conquer a city.” If people can make you angry, they can control you. So, why do you want to give up control to every little insignificant person walking along? From that point on, I found it much more interesting to watch people try to make me angry, knowing that they weren’t going to succeed. I almost made a game out of it. I was able to take myself out of the center of the equation, to look at things from other people’s perspective, not to feel that all the rights belong to you. Once you can do that, the things that make you angry become few and far between.

You went on to graduate from Yale and the University of Michigan medical school. How did you come to specialize in pediatric neurosurgery?

Benjamin Carson: Pediatric neurosurgery became fascinating to me, more because I didn’t like adult neurosurgery, in the sense that there were so many chronic back pain patients in adult neurosurgery, and they never got better no matter what you did until they got their settlement. So, it seemed like there were just so many secondary game issues and things. With children, what you see is what you get. You couple that with the fact that I like to do complex things. You can sit there and you can do these enormously complex operations on old people, and it might be successful, and your reward is they live for five years. Whereas with a kid, you do this incredibly complex thing and your reward may be 50, 60 or 70 years. So I like to get a big return on my investment. So, I’d rather go with the kids.

Isn’t it harder?

Benjamin Carson: It is more difficult in the sense that they’re smaller, you can’t afford the blood loss. But the big bonus with the children is the phenomenon we know as plasticity. All the neurons haven’t decided what they want to do when they grow up yet. So consequently, you can be more radical in terms of some of the things you do. For instance, the hemispherectomy, you can’t get away with that in an adult, but a child has the ability to actually transfer functions to other parts of the brain. So you can take out half of the brain of a kid, and you’ll see the kid walking around, you’ll see him using the arm on the opposite side, and in many cases even engaging in sporting activities.

How do you determine that a hemispherectomy is required? That must be the last resort.

Benjamin Carson: Right. We will do hemispherectomies in children who have intractable seizures; that is, they cannot be controlled. If the seizure focus is all in that one hemisphere, the surgery can be extraordinarily effective. This is one of the best examples of what teamwork does. We have to have a pediatric epileptologist evaluating these people, and then you have to have a surgeon who can do the work. I always say good surgeon and a bad candidate is a bad result, just like a bad surgeon and a good candidate would be a bad result. You’ve got to have good preoperative evaluation, and you’ve got to have good surgery and good postoperative care.

Weren’t you one of the first surgeons to perfect that operation?

Benjamin Carson: I was one of the first people to really revive it.

The very first hemispherectomy was done at Johns Hopkins 70 years ago by Walter Dandy, in an attempt to cure a malignant brain tumor. The procedure was brought back by MacKenzie and a few other people, and then fell into disfavor. At the time that I did my first one in 1985, it seemed like something new. An article came out in The Washington Post, and we started getting all kinds of calls from people. A couple of medical students from the Boston area called and said, “We read about you taking out half the brain to stop seizures, and we talked to our neurosurgeons, and they said that we were mistaken and that we hadn’t read it right.” Over the course of time, it’s become much more widespread again. The key thing is not so much that I was this wonderful surgeon, but I came and relooked at it at a time when I think we had much better tools, much better ways of evaluating things and controlling things, and I think that makes a big difference.

As Solomon said in Proverbs, “There is nothing new under the sun.” It’s a matter of relooking at things, particularly in light of advancements. It was the same way with separating Siamese twins. I looked at that situation. I said, “Why is it that this is such a disaster?” and it was because they would always exsanguinate. They would bleed to death, and I said, “There’s got to be a way around that. These are modern times.” This was back in 1987.

I was talking to a friend of mine, who was a cardiothoracic surgeon, who was the chief of the division, and I said, “You guys operate on the heart in babies, how do you keep them from exsanguinating” and he says, “Well, we put them in hypothermic arrest.” I said, “Is there any reason that — if we were doing a set of Siamese twins that were joined at the head — that we couldn’t put them into hypothermic arrest, at the appropriate time, when we’re likely to lose a lot of blood?” and he said, “No.” I said, “Wow, this is great.” Then I said, “Why am I putting my time into this? I’m not going to see any Siamese twins.” So I kind of forgot about it, and lo and behold, two months later, along came these doctors from Germany, presenting this case of Siamese twins. And I was asked for my opinion, and I then began to explain the techniques that should be used, and how we would incorporate hypothermic arrest, and everybody said “Wow! That sounds like it might work.” And, my colleagues and I, a few of us went over to Germany. We looked at the twins. We actually put in scalp expanders, and five months later we brought them over and did the operation, and lo and behold, it worked.