At that time, it was never acceptable that a black player was the best.

William Felton Russell was born in Monroe, Louisiana, a small agricultural community where his parents were subjected to the constant indignities that were the lot of African Americans in the Deep South at the time. His parents, Charles and Katie Russell, decided they would not raise their children in this environment. They migrated to Oakland, California, where Mr. Russell found work in the shipyards during World War II. Life in Oakland was difficult and the Russells often lived in public housing projects, but their father’s refusal to submit to discrimination was a source of pride to Bill Russell and his older brother, Charlie. Their parents encouraged them to work hard and excel. Charlie L. Russell would become a noted playwright, while Bill Russell earned lasting glory on the basketball court.

The game did not come easily to Bill Russell. Although he eventually grew to be more than six feet ten inches tall, he struggled at first to find his footing on the hardwood. He was dropped from his junior high school team, and barely made the junior varsity when he entered McClymonds High School in Oakland. A left-hander, he created a unique, innovative style of defensive play, jumping to block shots in a way that had never been seen before.

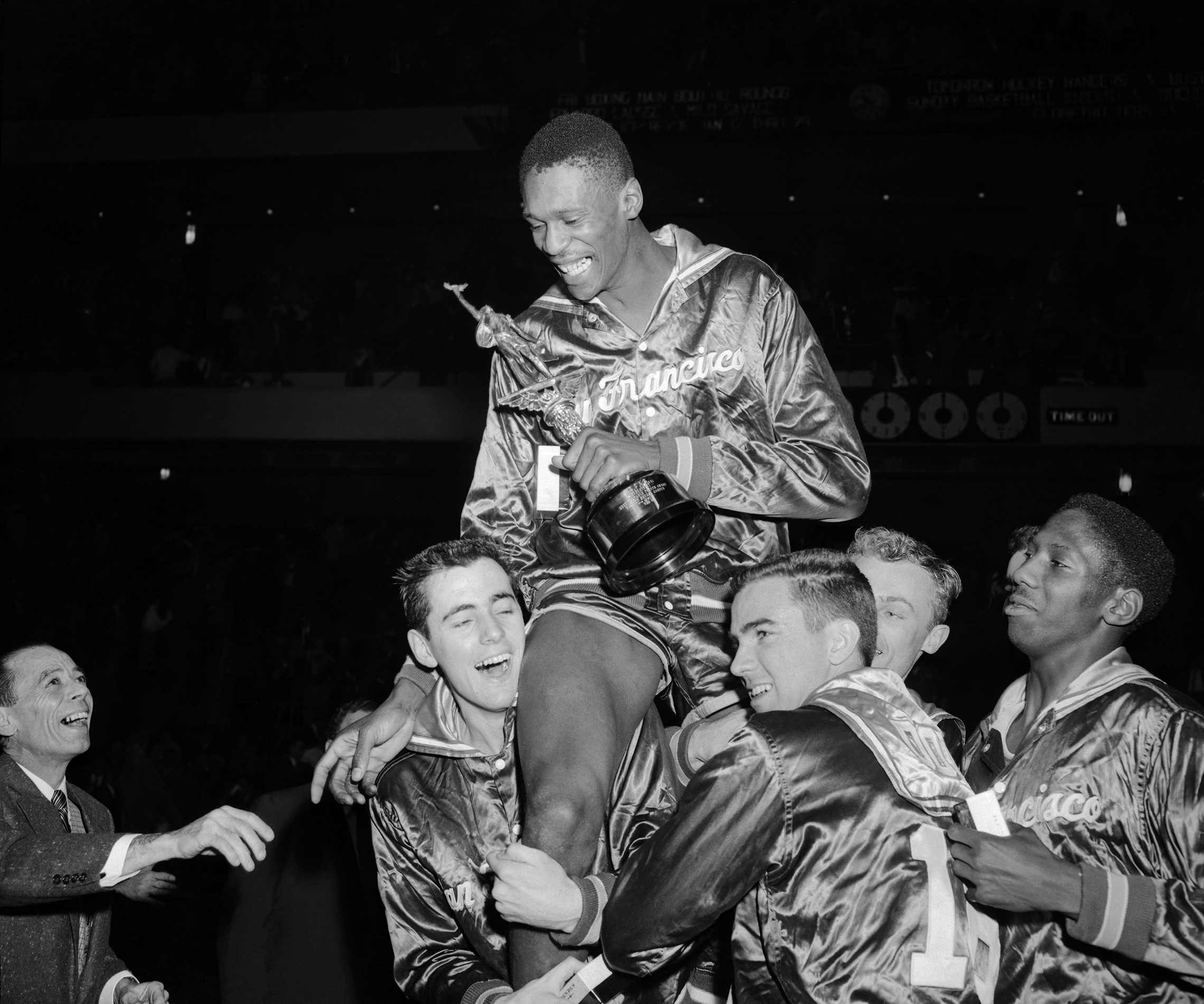

In high school, his team won three state championships, but his unorthodox playing style was not well understood by college scouts. The only school to offer him a basketball scholarship was the University of San Francisco (USF). African American players were still a rarity in college basketball, and the USF team, with Russell as captain, was the first to feature three African Americans in a starting line-up. Crowds on the road, and even at home in San Francisco, were sometimes vocally hostile toward Russell and his teammates. When Russell and the other black players were denied hotel accommodations in Oklahoma City during the 1954 All-College tournament, the white players on the team chose to stay with them in a vacant college dormitory.

Russell refused to let these experiences demoralize him and continually exceeded expectations on the basketball court. While at USF, he also competed in track and field, distinguishing himself in the 400 meters and the high jump. Russell applied these skills to the game of basketball, leading San Francisco to two consecutive national championships in 1955 and 1956. His prodigious defensive playing transformed the college game and made a deep impression on UCLA Coach John Wooden, among others. After the 1955 season, the National Collegiate Athletic Association instituted a number of rule changes, known as “Russell’s Rules,” to adapt to his powerful influence on the game. It was clear that as soon as he graduated, he would be joining the professional National Basketball Association.

As a college player, Russell had caught the eye of Red Auerbach, the legendary coach of the NBA’s Boston Celtics. Auerbach engineered an elaborate series of trades with other teams to secure Russell’s contract. Russell’s college coach, Phil Woolpert, had sometimes been skeptical of Russell’s novel defensive style, but Auerbach realized that Russell’s powerful defense was just what he needed to turn the Celtics from a good team into a great one.

Before Russell could join the Celtics, he had one more tournament to play as an amateur. He led the United States national basketball team in the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne, Australia. Russell was so eager to compete in the Olympics, he later told friends, that if he hadn’t been on the basketball squad, he would have competed in the high jump. Melbourne was another victory for Russell, with the U.S. team defeating the Soviet Union 89 to 55 in the final game.

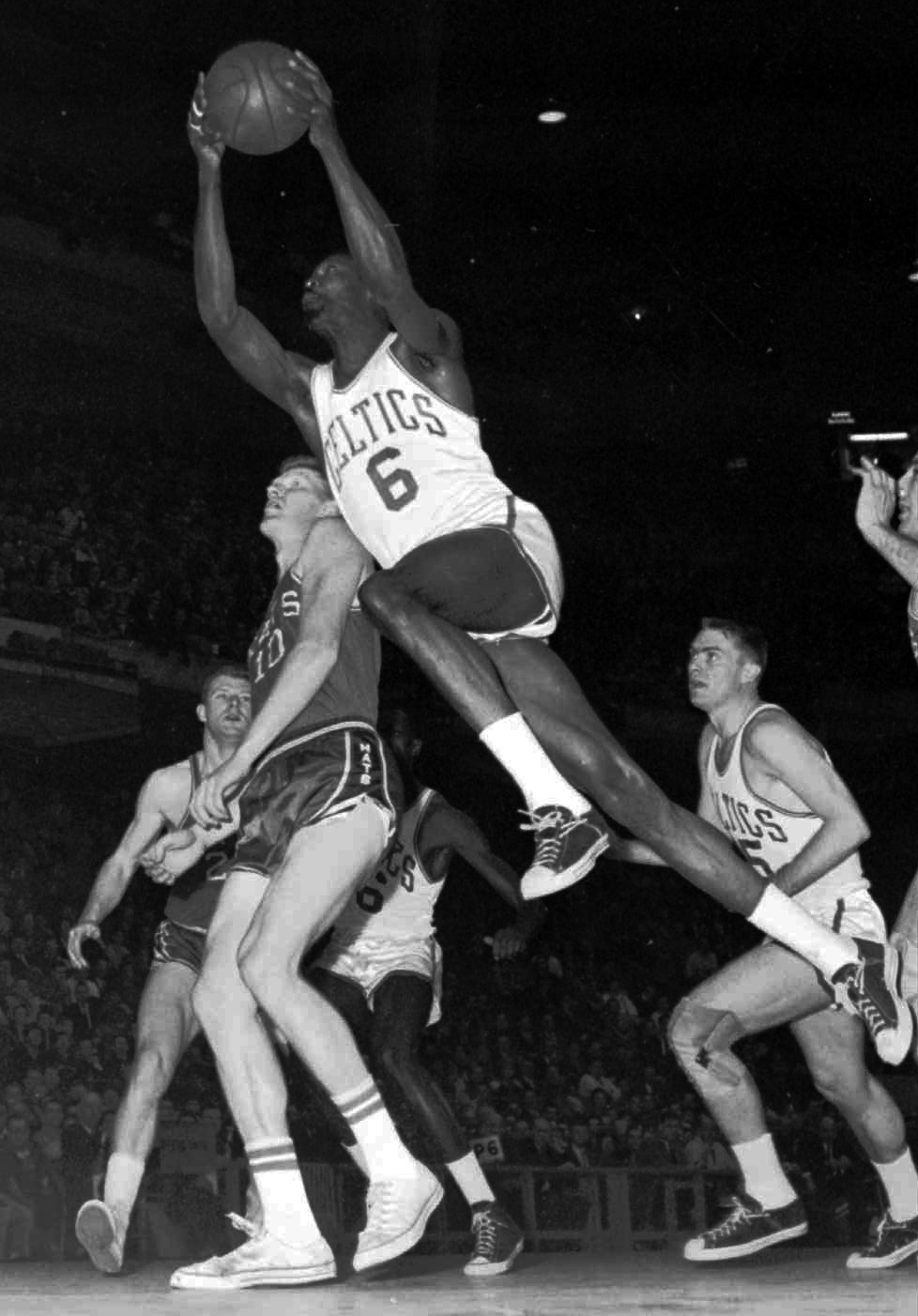

Bill Russell joined the Celtics with the 1956-57 season already in progress, and soon led the league in average rebounds per game. With Russell on board, the Celtics easily made it to the NBA finals, facing off against the St. Louis Hawks. After six games, the tournament was deadlocked. In the decisive seventh game, Russell made one of the most famous plays in basketball history, the so-called “Coleman Play,” bounding with lightning speed from baseline to midcourt to block a shot by Hawks guard Jack Coleman. Russell’s teammate, Bob Cousy, remembered it as “the greatest physical act I’ve ever seen on a basketball floor.” The Celtics won the game 125 to 123, securing their first NBA Championship.

Expectations were high for Russell’s second season in the NBA. Once again, he led the league in rebounds, and he led the Celtics to the NBA finals for a rematch with the Hawks. In the third game of the series, Russell injured his ankle, removing him from the game, and the Hawks prevailed. It was the only season in which Russell played for Coach Red Auerbach that the Celtics failed to take the national championship. Nevertheless, Russell was named the league’s Most Valuable Player.

By the following autumn, Russell was fully recovered and playing better than ever. For the next seven seasons he never averaged fewer than 23 rebounds per game. The Celtics also broke a league record by winning 52 games in the 1958-59 season. The Celtics easily regained the national title in a decisive rout of the Minneapolis Lakers. Russell’s uncanny ability to anticipate each player’s moves — and even the direction the ball would tip from the rim of the hoop — completely intimidated his opponents.

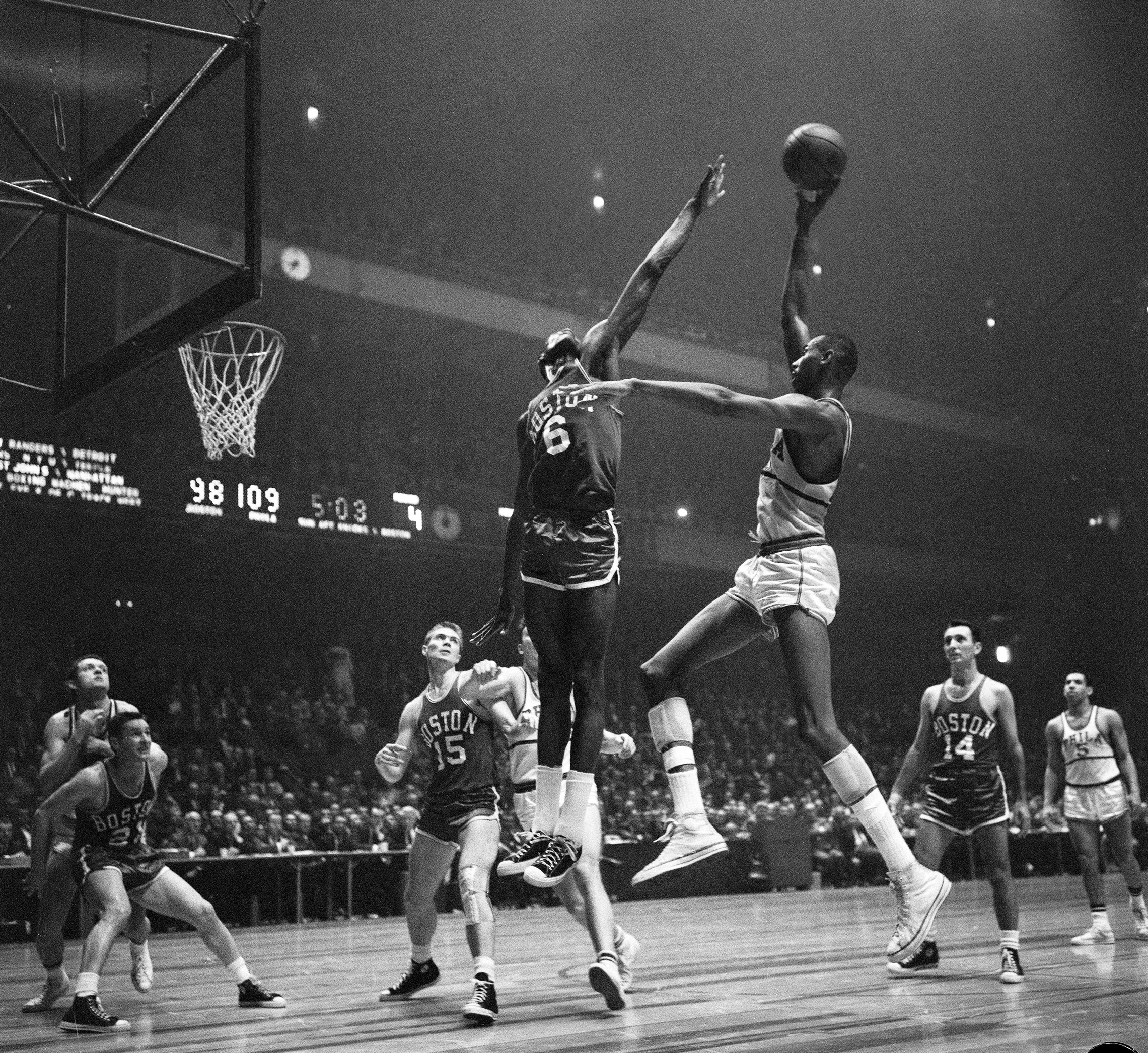

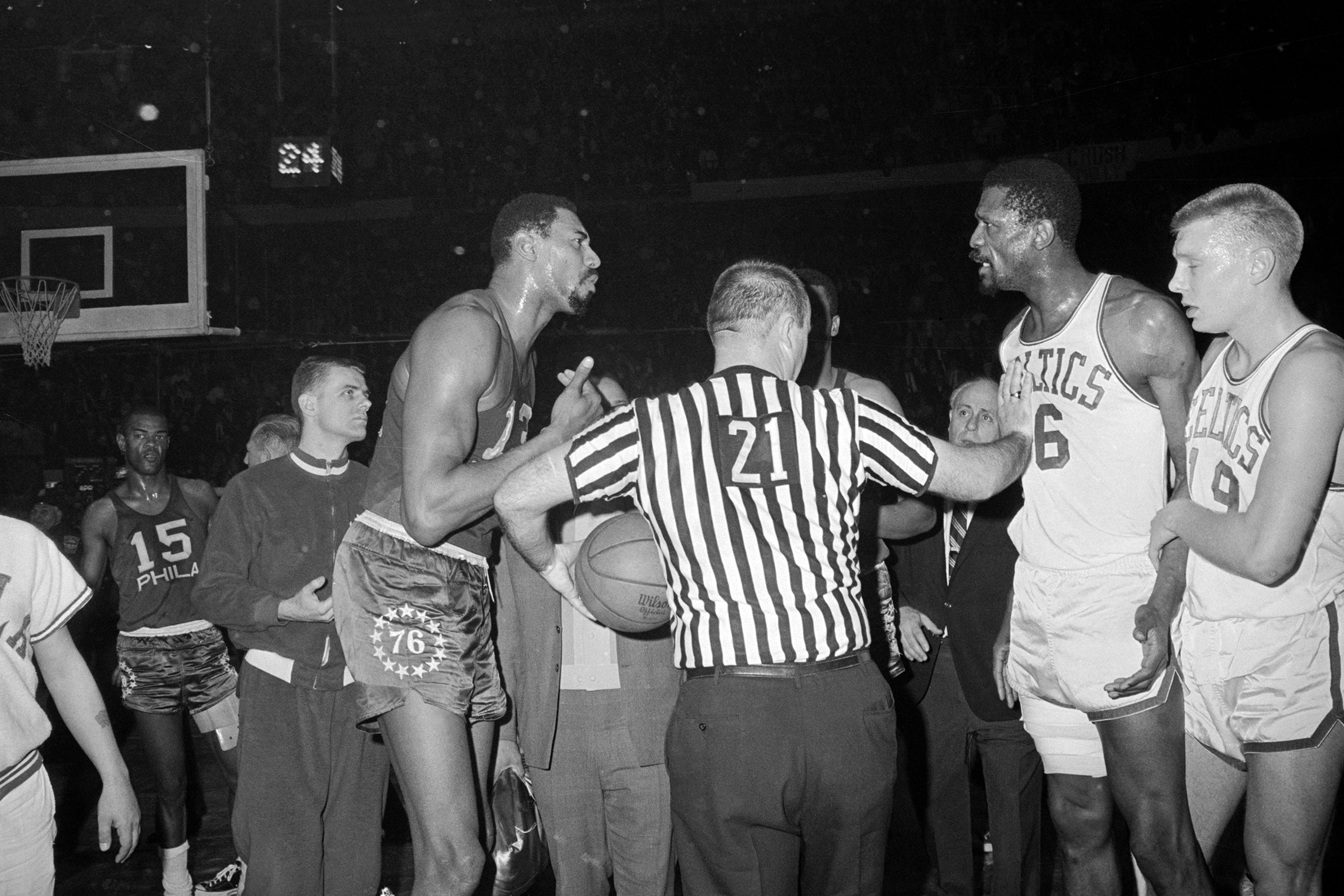

The 1959-60 season was the first in the most famous rivalry in the history of professional basketball. The Philadelphia Warriors had acquired the seven-foot-plus Wilt Chamberlain, a player who towered over even Bill Russell, and boasted offensive skills as formidable as Russell’s defense. Chamberlain personally outscored Russell by 81 points in the Eastern Division finals, but Russell’s incomparable sense of strategy and teamwork led to a four-to-two series win for the Celtics. The Celtics faced their old rivals the St. Louis Hawks again in the year’s finals, where Russell’s Celtics prevailed in a close-fought seven-game contest. Russell’s awesome rebounding ability came to the fore in this series; only Chamberlain would ever better his performance in that category.

The following season was another romp for Russell and the Celtics. As if on schedule, they defeated the Syracuse Nationals in the Eastern Division and beat the Hawks four games to one in the 1961 NBA finals. Russell received his second Most Valuable Player award. The next season saw Russell reach his peak in scoring. The Celtics broke their own record, winning 60 games, and Russell was voted Most Valuable Player for a third time. In the finals, the Celtics again defeated the Lakers, who had moved from Minneapolis to Los Angeles. Russell demonstrated a unique capacity to thrive under maximum pressure, scoring 30 points in the decisive seventh game to secure the Celtics another championship.

In 1962-63 Russell was named Most Valuable Player in the NBA for the fourth time, and also won Most Valuable Player honors in the All-Star game. The Celtics faced the Los Angeles Lakers in the finals, and fought each other to a draw in the first six games. In a double-overtime seventh game, Russell scored 30 points and made 40 rebounds to retain the championship for the Celtics.

As a highly visible public figure in the years when the country was emerging from a century of legally sanctioned discrimination, Russell threw his prestige behind the emergent Civil Rights Movement, participating with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the historic 1963 March on Washington. Russell’s years of living in Boston were not easy ones. At the height of the Celtics’ success there were many empty seats in the Boston Garden, while less successful teams in other cities played to full arenas. When Russell bought a fine home for his family in a historically white neighborhood, he received threats and insults. On one occasion, vandals broke into his home and splattered the walls with filth and graffiti. Unbowed, Russell focused his energies on his game, and enjoyed excellent relations with his teammates and other NBA players.

By 1964, Russell’s on-court nemesis — and off-court friend — Wilt Chamberlain had moved to San Francisco with the Philadelphia Warriors and faced Russell’s Celtics in the 1964 NBA finals. The Celtics scored a sixth consecutive victory, establishing a winning streak unmatched by any professional sports team in U.S. history. Russell had his best season ever for rebounds; his 24.7 per game average even exceeded Chamberlain’s that season.

The following season found Russell and the Celtics breaking records again, with 62 victories in one season. Russell led the league in rebounds and was voted Most Valuable Player for the fifth time. He found himself facing Chamberlain again in the Eastern Division finals, as Chamberlain had returned to Philadelphia to play for the 76ers. Russell suppressed Chamberlain’s devastating offense, and enabled his team to prevail in a seven-game playoff series. By comparison, the NBA finals were relatively easy that year, with the Celtics besting the L.A. Lakers in four games out of five. In the 1965-66 season Russell prevailed more easily over Chamberlain and the 76ers in four games out of five, but faced stiffer competition from the Lakers in the finals, dispatching them after a closely fought seven-game series.

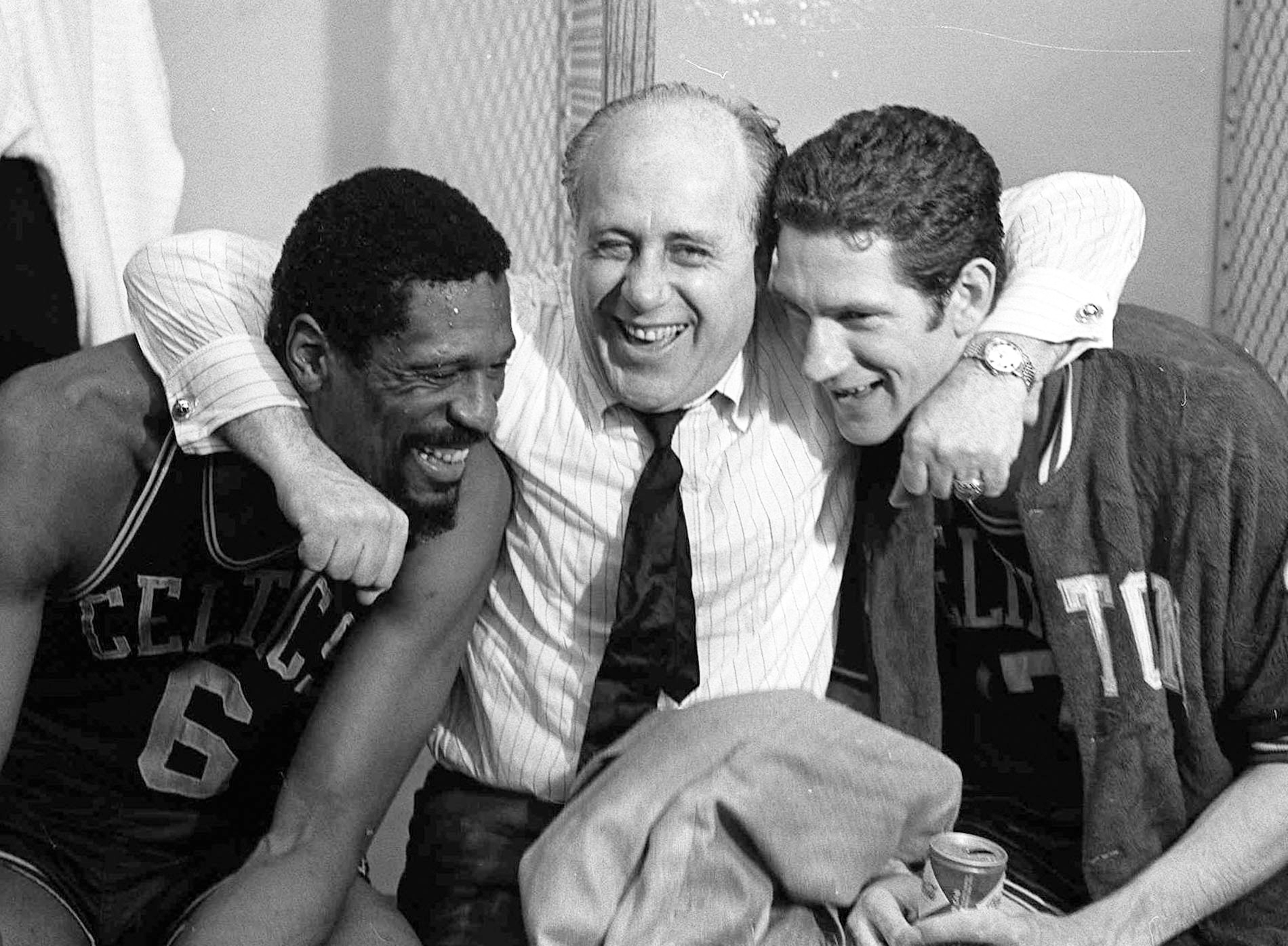

The Celtics had set the record of eight consecutive national championships. No other team in any sport has ever come close to this record. Russell’s awesome rebounding performance had finally begun to slip, however, and the team faced an even greater challenge with the retirement of their coach, Red Auerbach. Russell had never played for another coach in professional basketball, and Auerbach so respected Russell’s importance to the team that he promised to name no successor without Russell’s approval.

Unable to agree on any other choice, Auerbach suggested that Russell assume the role of coach himself, while continuing to play on the team. As Auerbach had never employed an assistant, Russell resolved that he too would serve without an assistant. The move was a bold one, not only because Russell had agreed to serve simultaneously as player and coach, but because no African American had ever coached a major league sports team in the United States.

Russell realized that serving as coach of the Boston team would be an opportunity to show what he could accomplish in a leadership position. The transition to coach was not an easy one. In the 1966-67 season, the Philadelphia 76ers, led by Wilt Chamberlain, finally broke the Celtics’ winning streak, defeating Russell’s team in the Eastern Division playoffs.

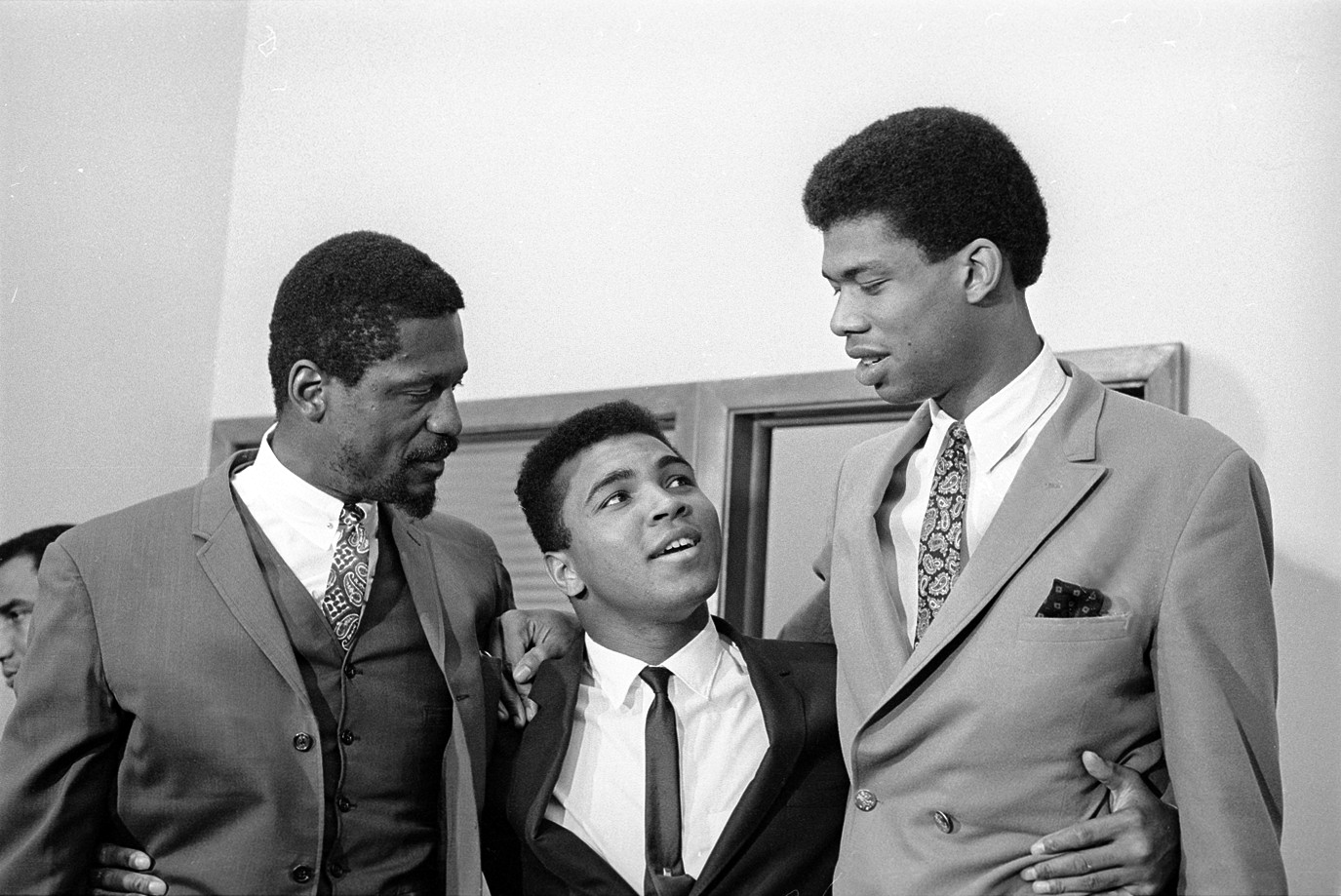

In 1967, Russell’s fellow athlete, heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali requested a deferment from the military draft, asserting that service in the Vietnam War would conflict with his Muslim religious beliefs. When the Selective Service denied his request, Ali refused to serve and was stripped of his championship title. While many athletes and celebrities rushed to disassociate themselves from the controversial boxer, Russell vocally defended Ali’s devotion to his beliefs. His defense of Ali did not endear Russell to the largely white Celtics following in Boston, but he remained steadfast in defense of his own principles.

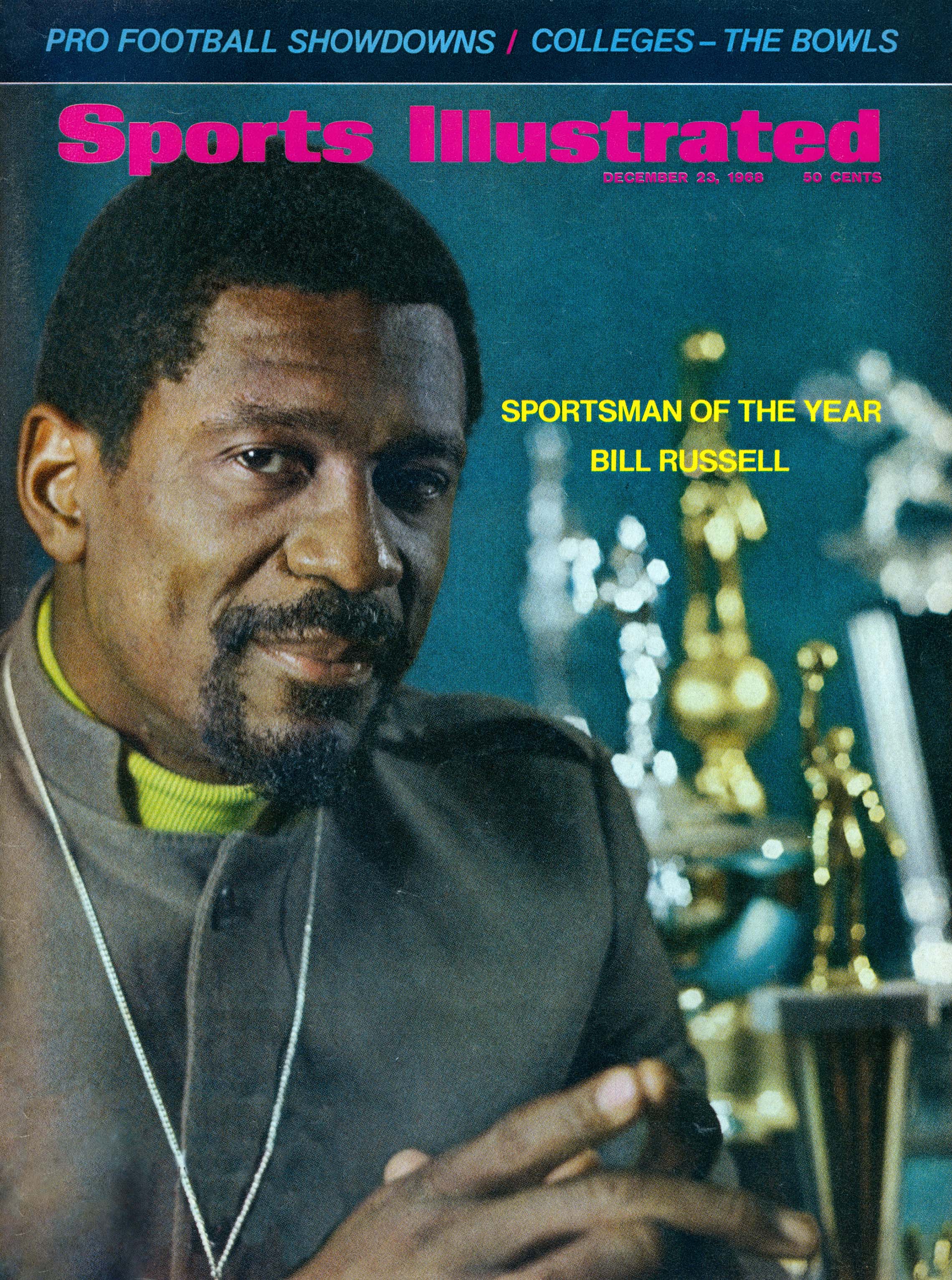

Though his powers as a player were finally waning, Russell threw himself into the task of coaching his team, and resolved to prevail in the 1967-68 season. Once again, the Celtics faced the 76ers in the Eastern Division playoffs, and the 76ers took three out of the first four games. Russell inspired his team to win two more games, tying the series. Again he led his team into a decisive seventh match, and once more, Russell rose to the occasion, successfully holding Chamberlain at bay. In the final moments of the game, he regained control of the ball, passing it to a teammate for the winning basket. Having clinched the division title, Russell led his team to a tenth championship, once again besting the L.A. Lakers in four out of six games. The sporting world stood in justified awe of the aging champion, and Sports Illustrated named him “Sportsman of the Year.”

The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the spring of 1968 was a traumatic event in America’s national life. Many African Americans felt alienated from their country after the violent death of a leader who had always preached nonviolence. Russell aligned himself with those who asserted the rights of African Americans to defend themselves against racist violence, and he was scourged in some quarters for these views, but he remained dedicated to both his career as an athlete and his convictions as a man.

Bill Russell played his last season in 1968-69. The rest of the Celtics line-up had aged along with him, and the whole team appeared played out through much of the regular season. Fourth-ranked as they entered the playoffs, Russell’s fighting sprit ignited the whole team, as one-by-one they bested more promising teams and headed for the finals again. This time, the Celtics faced the most formidable opposition of all, the strongest team in the Western Division, the Los Angeles Lakers, augmented by the addition of the most dangerous offensive player in the league, Wilt Chamberlain. The Celtics matched the Lakers game for game until the tournament was tied at three to three. In the dramatic seventh game, an injured Chamberlain left the floor and Bill Russell’s Celtics won their eleventh national championship. Although he was 35 years old, Russell played like a far younger man in this, his final game as a professional player.

Russell retired from the Celtics after the 1969 finals. He had succeeded in everything he had ever hoped to achieve in Boston, but had never felt welcome there. On retirement, he left the city behind. In his absence, the Celtics failed to reach the playoffs for the first time in 20 years. In 1972, Russell’s jersey, Number 6, was officially retired by the Celtics. Just three years later, he was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. He declined to attend either ceremony, apparently still stung by his experiences in Boston.

From 1973 to 1977, Russell served as coach of the Seattle Supersonics, taking the team to the playoffs for the first time. Although he never found the success in Seattle he had enjoyed in Boston, the team’s eventual success under Coach Lenny Wilkens showed the soundness of Russell’s defense-oriented strategy. Russell also lent his expertise to broadcast coverage of the NBA as a color commentator, and coached the Sacramento Kings from 1987 to 1988.

He has written a number of bestselling books, collaborating with the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Taylor Branch on an outspoken memoir, Second Wind (1979). More recently, he collected his thoughts on basketball, life and leadership in the book Russell Rules (2002). In recent years, he has become very much the elder statesman of the game, brokering a truce between feuding superstars Shaquille O’Neal and Kobe Bryant. In 2006, the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame was founded, and honored Bill Russell in its inaugural class. He was one of only five to be so honored, along with UCLA Coach John Wooden.

Of all his accomplishments, Bill Russell may be proudest of his achievements as the father of three children, including the noted attorney and television commentator Karen Russell. The years have healed many of the wounds of Russell’s difficult tenure in Boston; his achievement as a trailblazer was recognized with the NBA’s first Civil Rights Award. In 2006, Bill Russell participated in the groundbreaking ceremony for the Martin Luther King Memorial in Washington, D.C., an overdue tribute to his old friend and comrade.

As race relations in the City of Boston have improved, Russell’s hard feelings towards the city have softened. In 1995 the Celtics celebrated the opening of their new home, the Fleet Center, with a ceremony “re-retiring” Bill Russell’s jersey. Surprising many, Russell attended the ceremony, along with Wilt Chamberlain and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. The sellout crowd gave Russell a prolonged standing ovation, an overdue moment of reconciliation between the old champion and the city of his greatest triumphs. Russell has since returned to Boston many times; in 2008 the city presented him with him one of its We Are Boston Leadership Awards and Russell gratefully acknowledged that the city had truly changed for the better. Russell shared a highly positive view of his years with the Celtics in a 2009 memoir of the late Red Auerbach, Red and Me: My Coach, My Lifelong Friend.

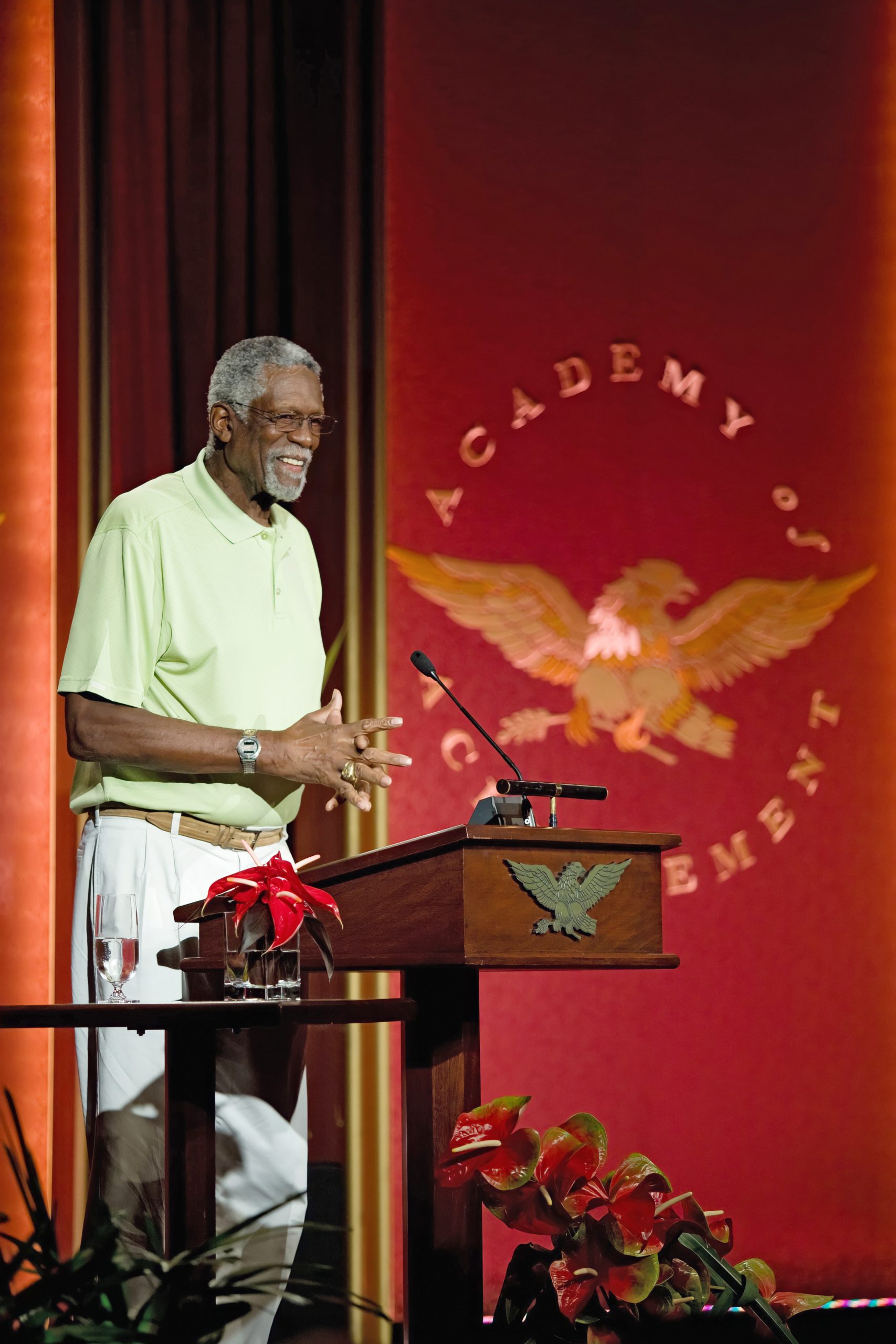

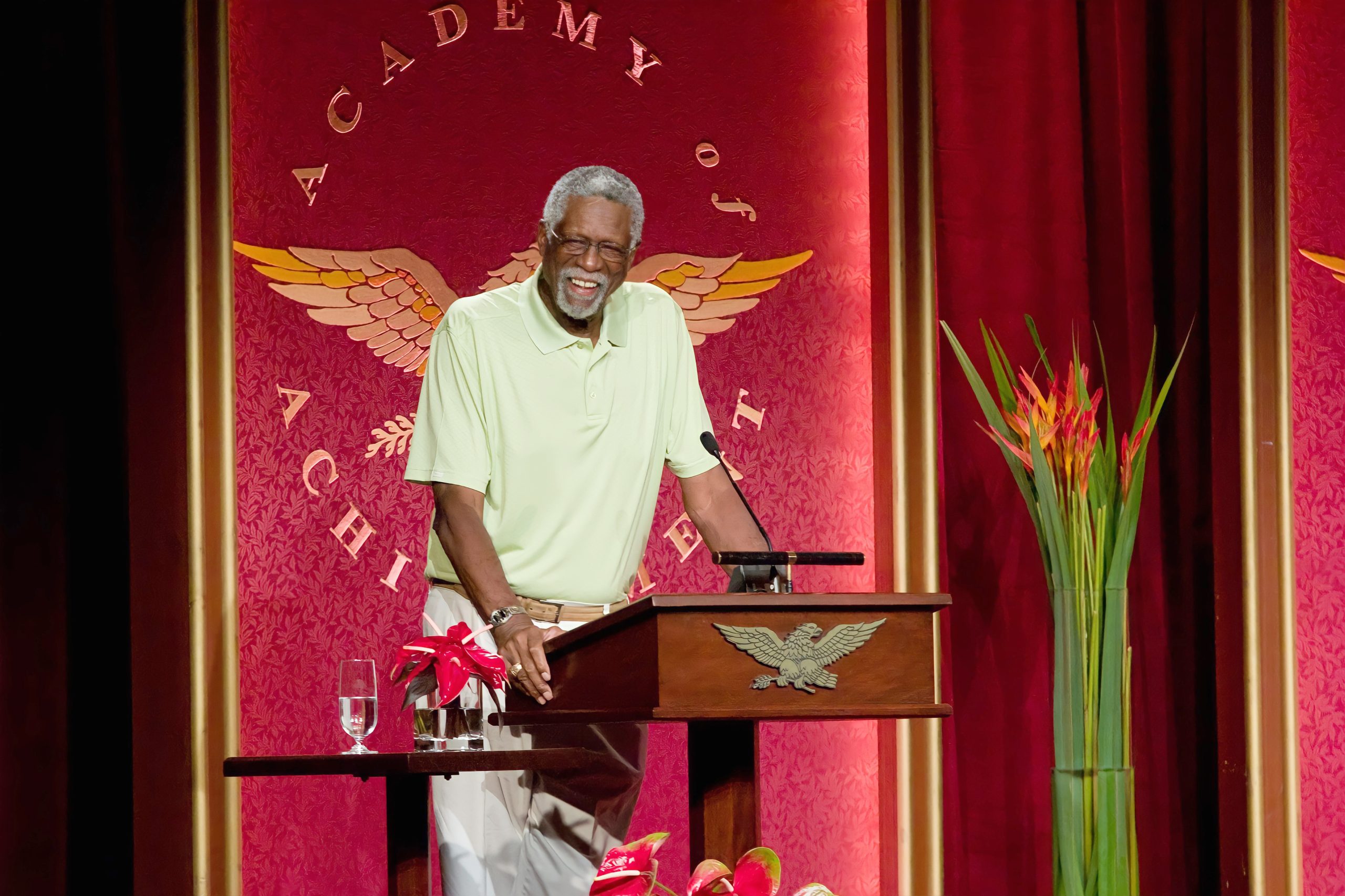

On numerous occasions over the years, Bill Russell has been called on by both the National Basketball Association and the U.S. State Department to represent his profession and his country abroad. As early as 1959, he was the first NBA player to visit Africa. Twenty years later, he made his first trip to China. He has now led basketball clinics in more than 50 countries on six continents, deploying his lifetime of experience to build bridges across the barriers that divide humanity. In 2011, President Barack Obama awarded Bill Russell the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

On July 31, 2022, Bill Russell died at the age of 88. On August 11, 2022, the National Basketball Association (NBA) and National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) announced they will honor the life and legacy of 11-time NBA champion and civil rights pioneer Bill Russell by permanently retiring his uniform number, 6, throughout the league. The iconic Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Famer will be the first player to have his number retired across the NBA.

Hailed as the greatest team player on the greatest team of all time, Bill Russell led the Boston Celtics in the longest championship streak in U.S. sports history. With a flair for defense never before seen on a basketball court, allied with an uncanny ability to excel under pressure and an indomitable will to win, Russell dominated the game of basketball from his earliest days as a student athlete to his triumphant career in the pros.

As captain of the Boston Celtics, he led the team to nine championships, including the unsurpassed streak of eight consecutive wins. In 1967, he succeeded the legendary Red Auerbach as the team’s head coach, becoming the first African American to coach a major league sports team in the United States. Serving as a player-coach, without an assistant, he guided the Celtics to two additional championships.

Bill Russell achieved this unprecedented record while facing down the incessant harassment and prejudice that hounded African Americans in the 1950s and ’60s. His courage and dignity in overcoming these obstacles have been an inspiration to all Americans.

In your first year in the NBA, you made perhaps the most celebrated play in professional basketball history. Can you tell us about the Coleman play?

Bill Russell: That was my rookie year. You see, up until that time, in general, rookies were not people yet. “All they do is cost you ball games, making rookie mistakes.” Well, Tom Heinsohn had one of the greatest games I’ve ever seen. He had 38 points and 23 rebounds, which was not a bad afternoon, and fouled out in the first overtime playing defense. Okay? And Frank Ramsey, who originated the six-man position, we had the last two points in the game, and we won by two in double overtime.

Getting into double overtime, I went, I made a “back-door,” and I got the pass too late to make the basket, so I went, I missed the shot and I went out. Well, they got the rebound uncontested and outlet it to a guy at half court, Coleman. And we didn’t have anybody past the top of the foul circle. So all he had to do was dribble down and lay it up. Well, I come back on the court, and I see what’s happening, and I take off. And I ran by everybody and I caught him. And when he got the ball at half court, I was still out of bounds on the baseline. And I saw nobody was going after him, so I went after him. And not being too modest, I was probably — if not the, closest to — the fastest man in the league. Nobody knew that though. So I caught him and I blocked his shot, and I didn’t knock it in the stands. I blocked the shot and kept it in play. I almost forgot about the play until Heinsohn and Cousy and those guys were talking about it that that was the greatest play they’d ever seen. I wasn’t going to let us lose, not standing around anyway. If we were going to lose, we were going to lose fighting.

You and Wilt Chamberlain had the most famous rivalry in basketball, but we understand you were actually friends off the court. What was that like?

Bill Russell: Wilt and I were — when he was playing in Philadelphia, we used to have a Thanksgiving night game in Philadelphia every year. It was like every year this… at noon he would come to the hotel and pick me up, and I would have Thanksgiving dinner with his family — you know, he had a lot of brothers and sisters — and his mother would let me take a nap in his bed after we had Thanksgiving dinner. And then we’d go to the game together. And as we left the home, she’d say, “You be nice to my boy!” And everybody thought for years and years that we were (rivals) because they projected. They didn’t know either one of us. We were not rivals. That’s what most people did not understand. That’s somebody that didn’t know either one of us. We were not rivals. We were competitors, which is a totally different thing, because in a rivalry there’s a victor and a vanquished. Neither one of us fit either side of that. We were competitors that played the same position in completely different ways. Both of us had our agendas, and our agendas were to win. Now he thought — and rightfully so — that he was the greatest basketball player that ever lived. And if he went out every night and performed as the greatest basketball player that ever lived, they should win a lot of games. So they won a lot of games.

My approach was it’s a team game. And the only important stat, if you want to call it that, is the final score. And so I was only interested in winning. But that goes back to my high school and college days. At that time it was never acceptable that a black player was the best. That did not happen. That’s like all the baseball players in the Negro leagues. They were never considered Hall of Famers or anything like that, although we found out later that they were just as good, if not better, than the so-called famous. So I’ll digress for just a minute. My junior year in college, I had what I thought was the one of the best college seasons ever. We won 28 out of 29 games. We won the National Championship. I was the MVP at the Final Four. I was first team All American. I averaged over 20 points and over 20 rebounds, and I was the only guy in college blocking shots. So after the season was over, they had a Northern California banquet, and they picked another center as Player of the Year in Northern California. Well, that let me know that if I were to accept these as the final judges of my career I would die a bitter old man. So I made a conscious decision: “What I’ll do is I will try my very best to win every game. So when my career is finished it will be a historical fact I won these games, these championships, and there’s no one’s opinion how good I am or how good other guys are or comparing things.” And so as I chronicle my career playing basketball, I played organized basketball for 21 years and I was on 18 championship teams. So that’s what my standard is: playing a team game and my team winning. I really applaud — and adore really — these great athletes, that play my game especially. So I feel humbled if someone wants to go past that and include me in that group, because I never include myself in that group.

Everyone includes you in that group now. You played in so many championship games against the L.A. Lakers, but you’ve mentioned that you have enduring friendships with several of them, contrary to what the public might have thought about the rivalry. You got a letter from Jerry West just recently. What did he say?

Bill Russell: He just said he honored and appreciated our friendship and how kind and considerate I’ve been of him throughout his whole career. And he wanted to thank me.

You see, when Jerry was a rookie with the (Lakers), that was the year that the Lakers moved from Minneapolis to Los Angeles. That’s where the name Lakers comes from, the Minnesota Lakers, because of all the lakes in Minnesota. When Jerry was a rookie, and we — the Celtics — came out to the West Coast to California and welcomed and introduced the Lakers to the West Coast. So we played I think 16 or 17 exhibition games, starting in San Diego all the way up to San Luis Obispo. And so we were just living together for a month. And Elgin Baylor — we had been friends since I was in college — and Jerry was a rookie and Elgin was a star, and Elgin sort of mentored Jerry. So everywhere Elgin went, Jerry went. And so we, all of us were, no matter who they were, rookies in the league. I know that all the people I know welcomed the rookies, because they could make our game better. And that’s what most of us were interested in, was making our game the best that we could make it.

Did Jerry West as a rookie show the promise of the player he would eventually become?

Bill Russell: Yes. He was very, very good. I think the only reason he wasn’t Rookie of the Year was because of Oscar Robertson. That does create a problem!

Jerry was a very, very competitive, very intelligent ballplayer. That’s one of the things that I like to tell folks about these great basketball players is that the greater they are, the smarter they are. And that no guy can reach the top of his field without knowing what he’s doing. The Lakers, like West and Chamberlain and Baylor, and a host of other guys who I knew quite well, they were at the wrong place at the right time, because you know, everybody says we beat the Lakers all the time. While that is true, the other thing you have to consider is we beat everybody! It wasn’t just the Lakers. A guy was telling me something about we lost one year and how I had had remarkable success against Wilt. I said, “If you can win eight straight championships you’ve beaten everybody.” There’s not one person that you said, “Well, I beat him.” You beat everybody! And that’s the way we felt about it. And as far as I can figure for myself, there was never any animosity towards other players.