I didn't feel beautiful when I was growing up. And I found my niche. I couldn't compete with girls who were thought of as beautiful, so I found my niche in music. And that was where I found my beauty.

Carole King was born Carol Joan Klein in New York City. She grew up in Brooklyn with her father — a firefighter — and her mother, a school teacher. Mrs. Klein loved music and the theater, and made sure her daughter was exposed to both. By the age of three, Carol (the final “e” came later) was showing an enthusiasm for music and a highly accurate sense of pitch. At age four, her mother began teaching her the rudiments of piano technique, music theory and harmony. Carol easily learned the popular songs she heard on the radio, and soon began writing songs of her own. At age 15 she auditioned for ABC Paramount Records and caught the ear of producer Don Costa, who placed her under contract. She recorded her first singles as a singer, without notable success, but continued to write music and learn the record business.

A precocious student, she graduated from high school at 16 and enrolled at Queens College, where she met Gerry Goffin, an aspiring lyricist. They married and quit school, working at day jobs and writing songs together at night. After a few minor sales they struck gold with “Will You Love Me Tomorrow.” Recorded by the Shirelles, it went to Number One on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, as the bestselling single in the country. It was the first record by an African American girl group to go to Number One, and on the strength of its success, Gerry Goffin and Carole King, still in her teens, quit their day jobs to become full-time songwriters.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, the Brill Building in New York City was the center of the nation’s music publishing industry. Publishers and record labels occupied dozens of offices in the building, and an army of professional songwriters pounded pianos in tiny studios, writing the songs for the first generation of rock and roll stars. Goffin and King were among the most successful of the era’s songwriting teams, writing hits such as “The Loco-Motion,” “Up on the Roof,” “One Fine Day,” and “Take Good Care of My Baby” for solo artists and vocal groups like the Drifters and the Chiffons. As the British-inspired wave of guitar bands took over the charts in the mid-’60s, many of them recorded Goffin-King tunes, with the Beatles covering “Chains,” Herman’s Hermits singing ”I’m Into Something Good,” The Animals introducing “Don’t Bring Me Down,” and the American television band the Monkees playing Goffin-King’s “Pleasant Valley Sunday.” The team’s collaboration reached its pinnacle with Aretha Franklin’s recording of “You Make Me Feel Like a Natural Woman” in 1967.

Although Goffin and King’s writing career was a success, in 1968 their marriage ended, and King moved with their two daughters to Los Angeles, the new center of gravity for the recording industry. King had recorded a few singles as a solo artist during her years with Goffin; in Los Angeles she began to focus for the first time on building a career as a performer. A short-lived band, The City, recorded one album, now a collector’s item, before breaking up in 1969.

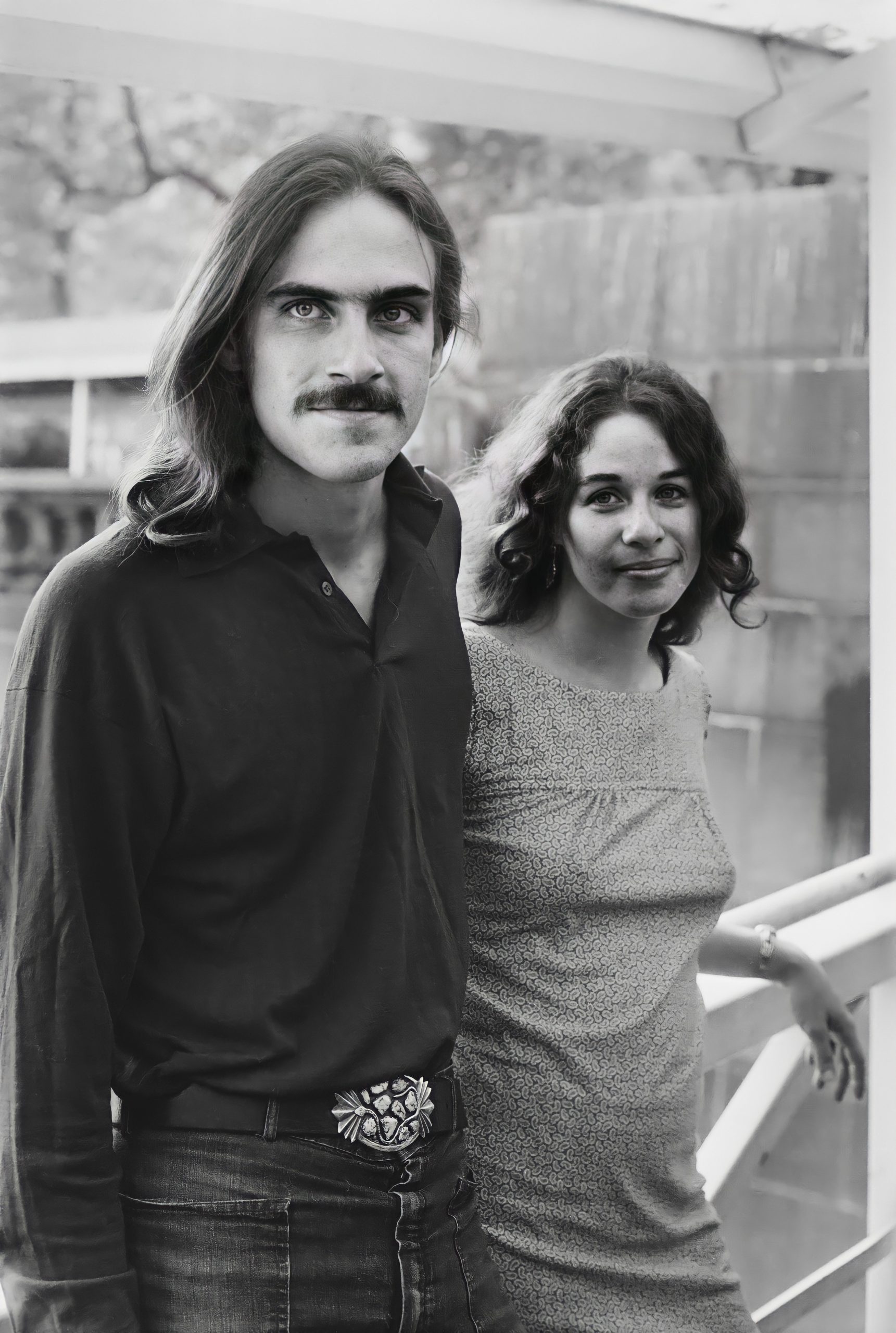

King was living in the hillside neighborhood of Laurel Canyon, overlooking the Sunset Strip and its legendary folk club, the Troubadour. Here, she formed friendships with other singer-songwriters, including James Taylor, Joni Mitchell and lyricist Toni Stern, who would become a frequent collaborator. In 1970 she married musician Charles Larkey. The couple would have a son and a daughter.

Carole King’s first solo album, Writer, failed to chart in 1970, but her next effort would change everything. Tapestry, released in 1971, included re-interpretations of some of her previous hits for other artists, including “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” and “You Make Me Feel Like a Natural Woman,” as well as the new songs “I Feel the Earth Move Under My Feet,” “It’s Too Late” and “You’ve Got a Friend.”

Carole King’s single of “It’s Too Late” went to Number One on the pop singles chart. as Tapestry was climbing the album charts. The album was the country’s bestseller for 15 consecutive weeks, and remained in the Top 100 for six years, selling 25 million copies worldwide. The album generated four Grammy Awards — a first for a female artist — Best Record (for the single, “It’s Too Late”), Best Song, Album of the Year and Best Female Pop Vocal Performance. For the next 25 years, Tapestry remained the bestselling album by a female artist.

King’s follow-up album, Carole King: Music, released in the last month of 1971, sold half a million copies in the first week, joining Tapestry in the Top 100 album charts and reaching Number One within a month of its release. It remained on the pop album chart for 44 weeks, eventually selling a million copies — a platinum record, in the industry’s terminology. Her next two albums, Rhymes and Reasons and Fantasy, were certified gold records for selling half a million copies each. At the peak of her fame and popularity in 1973, Carole King performed a free concert in New York’s Central Park, attended by over 100,000 people.

Wrap Around Joy sold half a million copies in its first year of release in 1974, and became the bestselling album in the country. Subsequent albums performed less well although King continued to record and collaborate with friends like James Taylor, David Crosby and Graham Nash, and resumed writing with her ex-husband, Gerry Goffin.

In 1976 her marriage to Charles Larkey ended in divorce. The following year, Carole King moved to rural Idaho with a new songwriting partner, Rick Evers. The couple married, but after Evers turned violent, she removed herself and her children to Hawaii. Evers died of a drug overdose shortly thereafter. King made a permanent home on a ranch in Idaho and became active in environmental causes, including the Alliance for the Wild Rockies, testifying before Congress on behalf of the proposed Northern Rockies Ecosystem Protection Act.

King continued recording through the 1980s and ‘90s and contributed songs to the soundtracks of The Care Bears Movie, Murphy’s Romance, A League of Their Own, and You’ve Got Mail. Over the years King has also made occasional appearances as an actress in film and on television. In the 1990s she appeared on Broadway in the musical Blood Brothers, and in Dublin, Ireland in Neil Simon’s Brighton Beach Memoirs.

At the beginning of the 21st century, King continued to record, perform and write, providing songs for both newer and more established artists, including k.d. lang, Steven Tyler, Celine Dion and Babyface. She toured the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand and recorded a successful live album. In 2007 she reunited with James Taylor for a series of sold-out shows at the Troubadour, where their performing careers had first taken off. In 2010 they took their double act on a highly successful tour of the U.S. and Australia, and recorded an album, Live at the Troubadour, that sold over half a million copies and remained on the charts for 34 weeks.

Carole King published her autobiography, A Natural Woman, in 2012. The New York Times bestseller made public for the first time the painful story of her abuse at the hands of third husband Rick Evers. King hoped that sharing her story would help other women to free themselves from abusive relationships.

In recent years she has limited her recording and performing activities, although she continues to appear on behalf of causes she believes in, campaigning for presidential candidates John Kerry in 2004, Hillary Clinton in 2008 and Barack Obama in 2012. In 2013 she and James Taylor performed a benefit concert for victims of the Boston Marathon bombing.

In many ways 2013 was a banner year for King, with the premiere of the Broadway musical Beautiful, based on her life and music. The show was a popular success and won two Tony Awards. That year, she received a Grammy Award for Lifetime Achievement and became the first female songwriter to receive the Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song, awarded personally by President Barack Obama. She received Kennedy Center Honors in 2015. The following year, she performed the entire Tapestry album live for the first time, at an outdoor concert in London’s Hyde Park.

In a composing career spanning six decades, Carole King has had more than 400 songs recorded by well over 1,000 artists, resulting in well more than 100 hit singles. No matter what changes occur in public taste, technology, or the economics of the music business in the years to come, singers and instrumentalists will continue to record and perform the songs of Carole King, and listeners will be as moved by them in the next century as they were in the last.

The most successful and admired female songwriter in the history of pop music, Carole King proves that one woman alone at the piano can be more powerful than a four-piece rock band or a 30-piece orchestra. At age 18, she scored her first Number One hit record – the first of 118 pop hits on the Billboard charts, including such classics as “Will You Love MeTomorrow,” “The Loco-Motion,” “Up on the Roof,” It’s Too Late, Baby,” “I Feel the Earth Move Under My Feet,” “You Make Me Feel Like a Natural Woman” and “You’ve Got a Friend.”

To date, she has recorded 25 solo albums, the most successful of which, Tapestry, sold 25 million copies, and for a quarter of a century held the record for a female artist for most weeks at the top of the charts. The recipient of the 2013 Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and the 2013 Gershwin Prize, she is a member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

For more than a half century, she has given voice to her innermost truth, and struck a resounding chord in the hearts of listeners around the world. Composer and performer, author and activist, she has brought the same passion, courage and unyielding honesty to her life, to her work, and to her defense of the woods and wildlife of her beloved Rocky Mountains.

So, in reading your book, you say that your mother exposed you to music while you were still in her womb. Why?

Carole King: My mother loved music and she had an eclectic collection of classical and show tunes and some popular music. So she just loved it and always listened to it, so I was exposed to it in the womb and as a child. I loved music and it made a lot of sense to me the gift that I have for it. I was able to understand it and learn it and recreate it.

You said that her mother actually encouraged her to be in music or theater or play the piano.

Carole King: It was important to my grandmother to have music in the house. My grandmother grew up in Russia and in her little small village, she was — my grandmother was the daughter of a baker and they didn’t have a lot of money. In her village, the girls with a lot of money her age had pianos in their living rooms. And so she dreamed that her daughter would play piano and she exposed my mother to music. And my mother’s real affinity was theater, but she learned enough music to pass on to me.

Could you tell us about your first recording?

Carole King: The first recording I ever made was “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” in a little recording booth in Coney Island. And I just remember it because, you know, I was with my mom and my dad and it was — it was a great experience, except that at the end for some reason I broke down crying. I was three, two or three.

Why did you cry?

Carole King: I don’t know. Because I was two or three probably.

At age four you started learning how to play the piano. Did you parents tell you that you were gifted?

Carole King: I don’t know if they told me I was gifted, and I don’t know if I knew I was gifted. I just liked it. I had almost perfect pitch.

What about the radio? Did that inspire you?

Carole King: Well, the radio was quite a wonderful thing. This was before television. One of the things I loved about radio is it stirred the imagination because you were only hearing it. You weren’t seeing what someone else thought you should see. And I remember many years later when MTV came along and they started making videos of songs. They really took away our ability to imagine for ourselves what — what the song evoked in each of us.

Were music and the arts something that your whole family valued?

Carole King: My mother always had an affinity for theater, which included music but her love was for — she wrote plays, she acted in them, she directed them. This was — she didn’t make a career out of it because her career at the time was being a homemaker and raising me.

I wrote a book about my journey called The Natural Woman. And I was able to see in writing the book all the different things that — different experiences I had that were unique to me, that informed who I am, and who I am now. As of this interview, I’m 72 years old, officially turned 72 earlier this week. And the journey includes having grown up and not thinking of myself as beautiful in the sense that most young girls were expected to be beautiful. There was an ideal that we were held to. I didn’t feel beautiful when I was growing up. And I found my niche. I couldn’t compete with girls who were thought of as beautiful, so I found my niche in music. And that was where I found my beauty. And I always knew I could do that. I always felt confident in doing that. And then as I grew up, I brought other, you know, insecurities, but I always knew that my music worked.

I married a lyricist. My first husband was a lyricist. And I wasn’t even thinking about being beautiful then. I was thinking about writing songs, and in that there was beauty. One of the things I admired about him was he had really — he’s still alive, but I’m thinking that we — he had great intelligence and he exposed me to ways of thinking about — I always liked to read. I always liked to go to plays. But he had a sensibility — my mother had the same sensibility. It was an understanding. I’m more instinctive about my understanding of things. They had the instinct of understanding, but also the ability to verbalize it, and make it an intellectual experience to talk about it. And I learned so much from Gerry and from my mother. And all of that went to inform my learning process. And then…

When Gerry and I eventually divorced, I had to find my own voice and my own way of thinking, but I brought to my life what I have learned from him. And I became a lyricist along with being a musician. The music was always there for me, always, always. It still is. It’s like I cannot do it for six months and when I need it, it just comes rushing out because that’s what I do. But the lyric writing, the understanding of intellectual processes that, you know — a Truman Capote play, for example, or, you know, there are just layers upon layers that I didn’t really understand but came to learn.

And then as I went through life and had other experiences, the experience of having success as a songwriter, it’s like, “Wow, this is great.” And becoming a singer. I was nudged into that by James Taylor, who taught me how to perform. Lou Adler, who gave me the confidence to make a recording as a recording artist on my own. I never wanted to be an artist. So now I’m a recording artist, and then I’m a performing artist. And all of this kind of unrolled. I never really had ambitions to do more than be a really good songwriter.

This is a journey, and alongside that journey my life experiences brought me to working on issues. I started out with Gerry working on civil rights issues in the ’60s. And then in the ’70s, you know, we demonstrated against the war, probably the late ’60s, but definitely ’70s as well. Late ’60s — it would have had to be actually mid-’60s. And then I gradually got involved in politics, not as a candidate, but working with people who had the power to make change. And that became really such an important part of my life, so important to me. It was a part of my life that wasn’t as public, but it’s so much a part of me. And as my two worlds developed together, I found my beauty and my purpose and my meaning and I found an understanding of all that.

So, as I sit here at 72, and I look back at my life, I realize, first of all, gratitude is my daily word. That is in my life, every cell of my body, every day. I just feel it all the time. And I’ve had a wonderful life so far. And, hopefully, I will continue to do that. And my goal in life — you know, people say, “What legacy do you want to leave?” Somebody asked me that recently. And the legacy I have left musically, I didn’t — I wanted to leave a musical legacy, but it more — it happened more than my pushing it. But the other thing that I do work on along with gratitude every day is being a mensch, being a good person. That is what drives me every day, to be a good person and try to realize the potential in this life with all the blessings that I’ve been given. Make it matter so that it carries forward to other people. And the opportunity to speak with you about this, hopefully, that will carry forward to other people.

You began to pursue a music career when you were so young. Where did you get that confidence?

Carole King: I have a level of chutzpah in that if there’s something that I would like to achieve, I don’t do it with arrogance but I think “Someone’s going to make it, why don’t I — you know, why not me?” And if you don’t try, you’ll never know. Maybe you could have achieved it. So there is that level of, “go for it.”

Could you tell us how you met Don Costa and what his influence was?

Carole King: I was a teenager when I first started going to record companies in New York. I was 15 and I loved the people that were making records then. And I thought, “Well, I want to do that too.” Not as an artist, but as a songwriter. And maybe at that time I thought, “Well, maybe I can sing them.” But I didn’t want to be a star or anything. I just wanted people to hear my music. And so I called up record companies and got appointments, because in those days you could. It was in the mid-’50s and you could get appointments. The music industry wasn’t a mammoth industry the way it is now. And there were things called A&R men, which were Artist and Repertoire — the people that actually knew music made the decisions and they had pianos in their offices. So I went for it and Don Costa recognized some talent. Don Costa was an A&R man. He was an arranger, producer, and he recognized my ability and let me make records and put them out.

A couple of years ago, Paul McCartney was in town to get the Gershwin Award, and he told a group of people that he woke up one day with “Yesterday” in his head. He went into the studio with John Lennon and said, “Do you know this song?” “No, I don’t know this song.” Where does that kind of inspiration come from? Is it something that you nurture or do you need a muse, someone to work with?

Carole King: Creativity comes in different ways. I’ve written with co-writers, and there’s a wonderful spark that happens when you write with a co-writer. Somebody, one of the two of you, it doesn’t matter which, says — puts out an idea and the other one, you know. It’s like any collaboration. You know, business people collaborate. There is that. There’s an idea. I don’t know where that comes from. That’s out of thin air.

You’ve written, “To this day, I can think of no greater musical joy than to hear a song arrangement come to life with instruments and voices.” Can you tell us what it’s like to hear your song on the radio?

Carole King: There are different stages.

Hearing your song on the radio is a big piece of it. You suddenly know, “Oh, my God, a whole lot of people are going to hear this.” But the stage for me is like — first of all, when an idea comes and I work on it and I shape it and, you know, it’s just a flowing thing that at the end of which, you know, I keep — I’ll reject something and then something will come in and I’ll fix it. So there’s — there’s inspiration, but there’s also the perspiration part where you actually craft a song. And then when I’m finished, I actually know when I’m finished. Some people say, “I’d work on it till they take it away from me.” But I actually know when it’s ready. And once it’s ready, that’s a first, “Oh, a song, where there was a nothing!” And then the playing of it for the first person you play it for, and you see in the person’s face and their reaction to it what you hoped you would see. That’s another level of appreciation that you go, “Oh, they like it!”

And then you record it, and that’s what you mentioned that I wrote about. The joy of imagining how an instrument would sound because it’s just me and my piano. And then it’s — all the things I hear that — a drumbeat, a guitar figure, violins, background vocals. And when you kind of hear them in your head, but, you know, then you actually hear them come to life and they’re better than you even imagined. That level of realizing. And then if I’m not the singer — and back in the early days I was never the singer. You give it to a recording artist who sings it and you go, “I can’t sing that well.” And by the way, I know I’m a good singer now, but — and what I bring to a performance is authenticity. But I can’t make those notes that Celine Dion or Aretha Franklin make. So hearing them sing those notes that I know I wanted to sing — sing them the way I wanted to, or to hear James sing “You’ve Got a Friend,” and the way that I imagined it might sound. That’s another level. And then the last stage is like hearing it on the radio or realizing that hundreds, thousands, millions of people are hearing it and that it’s meaningful to them. That’s — those are the stages. And it all starts with that little spark of idea that comes from whoever, whatever, wherever, through me.

This has been terrific. Thank you very much.

Carole King: Thank you.