I must have been 12 years old. I remember it was raining. We passed by the National Gallery, and that wonderful pink marble, in the rain it gets a very rich rose. I remember looking up and saying to my parents, ‘That’s the kind of job I would like to have some day.’

John Carter Brown was born in Providence, Rhode Island. His family had been prominent since before the Revolution, providing the initial endowment for what is today known as Brown University. His parents shared a passion for the arts and public service. His father, John Nicholas Brown, served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy under President Truman. While living with his family in Washington, D.C., the young J. Carter Brown fell in love with the National Gallery of Art and first conceived of a career that would allow him to pursue his love for all the arts and to share them with a larger public.

Although he was already committed to a career in arts administration, Brown spent his undergraduate years studying history and literature, and acquired a master’s degree from Harvard Business School. With this preparation, he immersed himself in the study of art history in Europe, including studies with the renowned art historian Bernard Berenson, and completed a second master’s degree in art history at New York University.

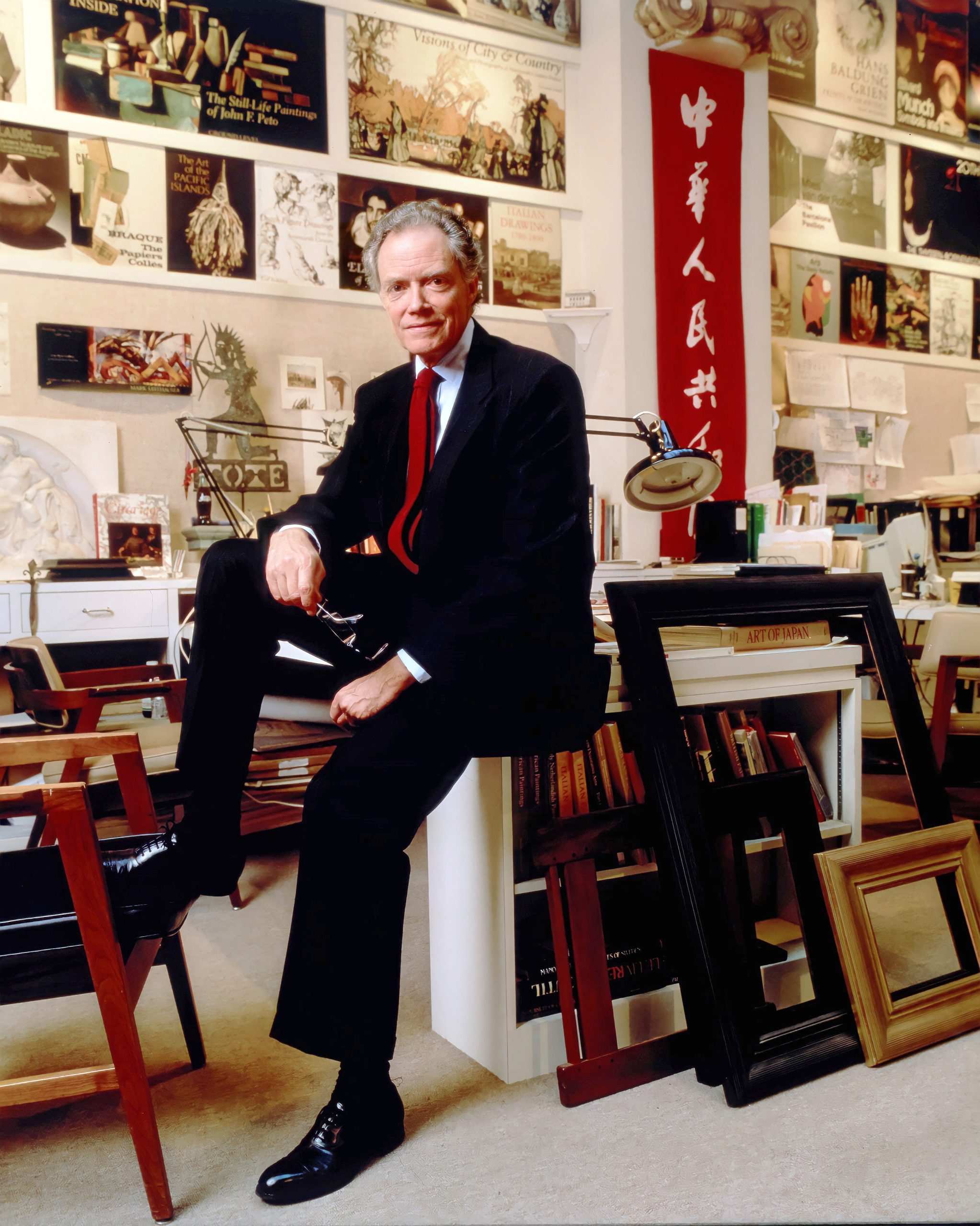

In 1961, Brown joined the National Gallery as an assistant to the director, John Walker. He was appointed assistant director in 1964, and in 1969, at the age of 34, he was appointed Director. He was only the third person to hold this position and would become the longest-serving director in the Gallery’s history.

Carter Brown was the first American museum director with a business degree. When he set out to raise $50 million for a new acquisitions fund, he overshot the target and raised $56 million. Even as public funding from the arts came under intense political attack, he induced Congress to increase the Gallery’s operating budget year after year, from $3 million in 1969 to $52 million when he retired in 1992. During his tenure, the Gallery’s endowment grew from $34 million to $186 million.

Having enjoyed an incomparable exposure to the world of art, and a thorough professional and academic training, Brown set himself a goal of bringing the joys of culture to a larger audience than the hermetic world of connoisseurs and art historians. In addressing the public, the Director always referred to the institution he headed as “your Gallery.”

With his special gift for diplomacy, Carter Brown persuaded foreign governments to loan priceless works for visiting exhibitions, and led American collectors to donate their treasures to the nation, including works by Cézanne, van Gogh, Picasso and Veronese. In his 23 years at the helm of the Gallery, he increased the collection by 20,000 works of art, including pieces by old masters and modern giants, from Leonardo da Vinci to Claude Monet, Henri Matisse, and Jackson Pollock.

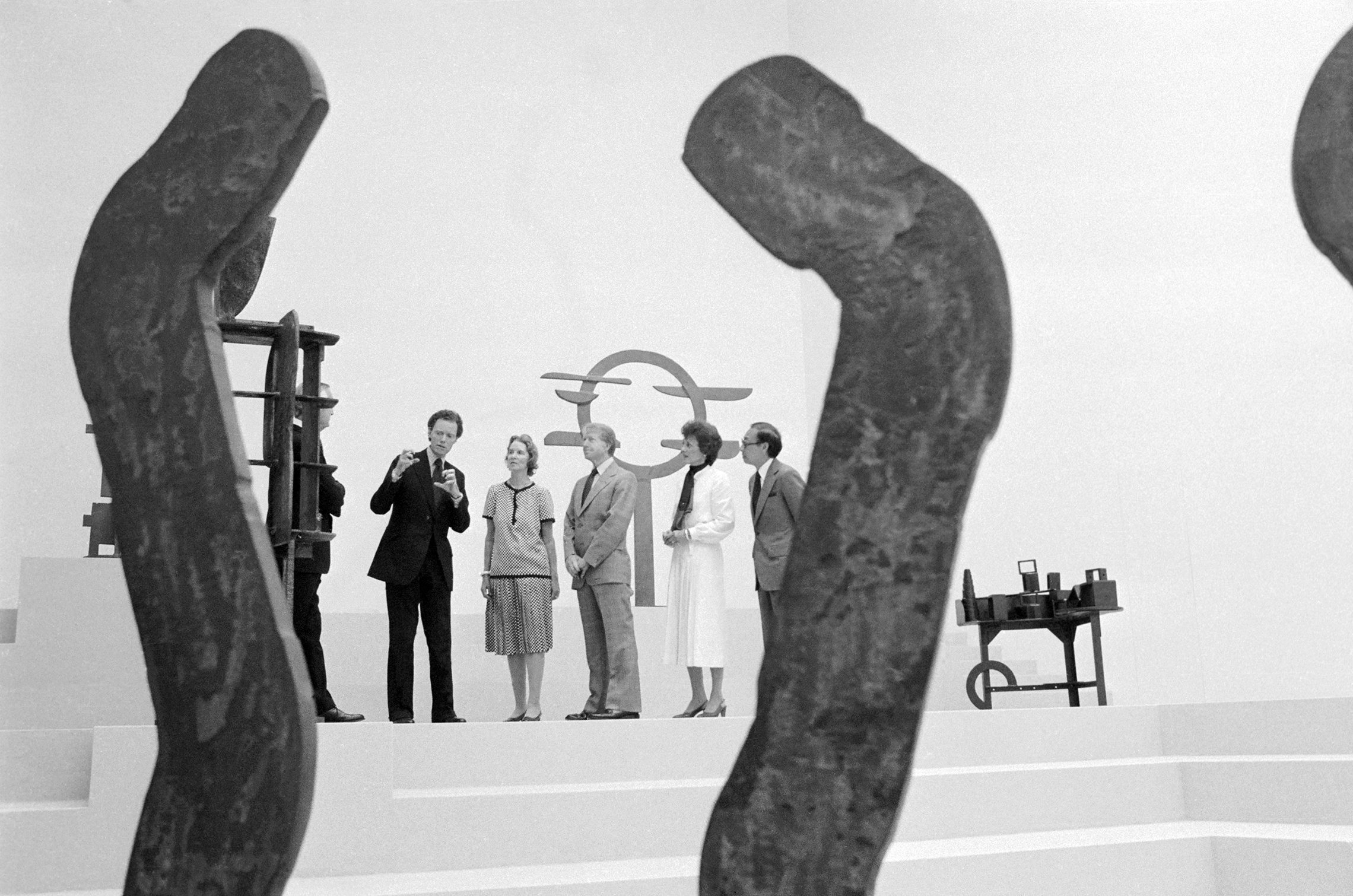

Combining rigorous scholarship with a unique theatrical flair, Brown instituted a series of dazzling special exhibitions. In 1977, “Treasures of Tutankhamen” inaugurated a new era of “blockbuster” museum shows. One exhibition alone, “Treasure Houses of Britain,” in 1985, attracted almost a million visitors. He also broadened the scope of the gallery beyond its traditional emphasis on European and North American art, with exhibitions of African sculpture, Chinese archaeological discoveries and the historic riches of Japan. Under Brown’s leadership, the Gallery’s annual attendance rose from 1.3 million in 1969 to almost 7 million visitors a year.

Brown greatly expanded the Gallery’s exhibition space, doubling its square footage. Perhaps his greatest triumph was the construction of the Gallery’s East Building in 1978. I. M. Pei’s angular modern design encountered fierce opposition from traditionalists and preservationists who feared it would spoil the view of the Capitol, but the finished building has become a major attraction for visitors to the city. Named to a list of the ten best buildings in America, it ignited an international trend of new museum buildings as innovative works of art. Brown ended his service to the Gallery on a high note, with “Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration,” an unprecedented extravaganza of art from five continents, marking the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s voyage to the New World.

After retiring from the National Gallery in 1992, he continued his crusade to bring the splendors of art to the mass public. He founded the cable television arts network Ovation and served as its chairman. During the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, he mounted a magnificent display of works from every continent and period of human history: “Rings: Five Emotions in World Art.”

His service to his adopted city continued until the end of his life. He served for 30 years as Chairman of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, an independent agency that advises the Federal and District of Columbia governments on matters of art and architecture that affect the appearance of the nation’s capital. In this capacity, Brown was a leading advocate of the controversial Vietnam Veterans Memorial, designed by 21-year-old Maya Lin. As with the East Building of the National Gallery, Carter Brown’s judgment was vindicated by the American people, who have made the Vietnam Memorial the most-visited site in the nation’s capital. Brown also played a crucial advisory role in the creation of the Korean War Veterans Memorial and the memorial to President Franklin Roosevelt.

In August 2000, Brown was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a terminal blood cancer. He confronted his illness with the same dignity and courage that had characterized his entire life and career. Six months before being interviewed by the Academy of Achievement, he received an autologous stem cell transplant and enjoyed an active life for the following year-and-a-half, before succumbing to a lung ailment in June 2002.

In his last years, he participated in a host of new building projects in Washington, D.C., including the Smithsonian’s American Indian Museum, and the National World War II Memorial. Through these works and the National Gallery of Art, the generous spirit of J. Carter Brown will contribute to the life of his country for many years to come.

“I was hopeless. I was very unathletic, and when I was in school I was two years younger than everybody in my class, so I got beaten up all the time, and I got laughed at for being interested in studying and doing stupid things like that.”

J. Carter Brown’s interests may not have won him many friends in school, but his subsequent career made him one of the best-loved figures in the cultural life of his country. For 23 years, he served as Director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., building one of the world’s greatest collections of art, and keeping it available to the public, free of charge.

He more than tripled the Gallery’s annual attendance, drawing record crowds with once-in-a-lifetime exhibitions like “The Treasures of Tutankhamun” and “Treasure Houses of Britain.” He doubled the Gallery’s exhibition space and massively enlarged its holdings, persuading collectors to donate their treasures to the nation. Critics howled when he commissioned architect I. M. Pei to build a modern gallery alongside the existing neoclassical structure, but the result was an undisputed triumph, named by the American Institute of Architects as one of the ten best buildings ever built in the United States.

When J. Carter Brown died in 2002, he was not only mourned as the man who had transformed a great arts institution, but as a populist who had brought great art to the masses.

How did you choose your career path? Was it something you planned from the beginning?

J. Carter Brown: I didn’t know what channel I would follow to carry out this idea of cultural administration. But it was very simple. I didn’t have enough talent to do any one thing superbly well. I couldn’t draw. I wasn’t that musical, although I’ve sung all my life in choruses. I wasn’t that good an actor. I didn’t do math, and didn’t do the visual expression that it would take to be an architect, although I loved architecture. And, I wasn’t going to be a poet. And, I wanted to achieve, so I figured the solution is to combine something so you can get a niche that other people haven’t got. So, I would go into the arts from an academic point of view, and I’d combine that with a business school degree. And then, I could market myself as a kind of cultural administrator, a kind of midwife for culture, and someone to arc the connection between an audience and the work of art, or of the arts. And so that was a career objective that I carved out for myself as a kid.

I was driving from the station in Washington, home to Georgetown. My father was working in the government, and I think I must have been 12 years old. I remember it was raining. We passed the National Gallery, and it was — that wonderful pink marble in the rain it gets very rich rose, and… I remember looking up and saying to my parents, “That’s the kind of job I would like to have some day.” Now, little did I know that I would actually be the director of that museum. But I felt that institutions had the stability to bring the arts to people, and perhaps art museums were the most stable because theater companies come and go, and there’s a lot of risk in the various performing arts and it’s sort of ephemeral. But, there’s something wonderfully permanent about those collections in art museums, and then you can use that as a base to bring in other art forms.

We had performing arts at the National Gallery. We have our own orchestra, one of the only museums that does have free concerts every week. We would bring dance groups in to relate to our Munch show or whatever. And then we had outreach. Our education system went out and reached, in my day, 80 million people a year. So out of this institution one had a kind of base, and that seemed to make sense.

How many graduate students from Harvard Business School in those days were thinking of going into the arts?

J. Carter Brown: In my day, I was the only one. I made my application on the basis that I wanted to go into cultural administration and in the nonprofit world. They took me in spite of that. Maybe they thought they could convert me. But, since then I understand that up to 20 percent of the business school class at Harvard are interested in the not-for-profit sector. So there’s been a tremendous sea-change. They accept women too, and that’s helped. They didn’t in my day. And they don’t let you do what I did, which was come — bang! — off from Harvard. You have to have worked. I would have gotten more out of the business school if I had worked before I went there. But I had a lot more education than I had in mind in the history of art.

I did not major in history of art as an undergraduate, and that was on purpose, on the advice of a hero of mine, the former director of the Metropolitan Museum, Francis Henry Taylor, who was just one of the most charismatic people. And, I went to see him and ask his advice about preparing for a museum career. So he said, “Well first of all, don’t major in fine arts.” I said, “What?” He said, “You’ll be doing that for the rest of your life. You’ll have to go to graduate school, you’ll be deep into it. Get a broad cultural background, so that what you do after that all has meaning.” And so, I majored in history and literature, which Harvard offered to a small percentage of the class, and which was a wonderful field. And I took some art history courses, but very little. I really got my art history aboard later.

What do you think your experiences overseas as a young man did for you?

J. Carter Brown: Oh, it changed my life. Being in a position where you don’t take anything for granted any more — you have to understand what it is to be an American.

Europe, you know, every few feet there is some extraordinary visual or cultural experience. My mentor, Francis Taylor, said, “You’ve got to go to Europe and wash your eyeballs in the stuff.” And it’s true. He had this great phrase, he said, “A museum is a gymnasium for the eye. The stuff,” he said, “that’s in America has been filtered through dealers. It’s only what’s movable, what’s fashionable at the time. In Europe you get things that are painted on the walls and they’re not going to move, and you’ve really got to expose yourself to that.” And now, of course, we have this global outlook that’s important, because there’s Asia to see. No one will understand a Japanese garden until you’ve walked through one, and you hear the crunch underfoot, and you smell it, and you experience it over time. Now, there’s no photograph or any movie that can give you that experience.

In any field there are many smart and talented people who do not succeed. Why do you think you succeeded?

J. Carter Brown: I was immensely lucky. I was at the right place at the right time, and I just had fortune smiling. That doesn’t happen to everyone.

Timing is really everything. When I got to be Director, I got into the files, and I saw that if I had gone through with my plan to get my doctorate and wouldn’t have been available to be hired as a lowly assistant to the director at the Gallery at that time, and then groomed to be Director very quickly, my then-boss had had another person all lined up. The “ifs” of history, these are the roads not taken. If I had just said, “No, I’m sorry, I’m not available for a year,” that would have been the end of a National Gallery opportunity. So it is useful to be where the lightning is coming down at a given moment. I credit a lot of what’s called “success” to just serendipity.

Weren’t you also well prepared?

J. Carter Brown: I was immensely prepared. I was eleven years in studying after getting out of high school. I had a year in Europe studying with Bernard Berenson, and traveling, and learning German, and going to the Louvre Museum school, and later the Hague Art History Bureau. And, I had both the business school and this very rigorous master’s at NYU Institute of Fine Arts, with this Germanic thoroughness, two-and-a-half years with a full-blown thesis, comprehensive exams in the whole history of art, and two language exams. And so, yes — and I’d had this fabulous opportunity growing up of exposure — but I’m interested in the inscription that is carved, apparently, over the lintel, the entrance of the institute founded by Fleming, the discoverer of penicillin: “Fortune smiles on those prepared to receive it.” And, you know, the Bermuda Race in yacht racing, my father called it “the great Atlantic lottery,” because where the Gulf Stream is, and what the weather is, is so fraught with accidental eventualities. And yet, when we were doing it, Carlton Mitchell won it three years in a row. And so, you know, there must be more to it than just luck.

You have suffered some disappointments and setbacks too. How do you deal with that?

J. Carter Brown: It’s tough. You lick your wounds, and you pick up and go on.

Talking of ocean racing, one of the best lessons I learned was the concept of the rhumb line, R-H-U-M-B. You lay down a course from Newport to Bermuda, and that’s your rhumb line. And then for some reason, you get blown off course. And, a lot of people make the mistake of saying, “Oh, we’ve got to get back to the rhumb line.” There’s a new rhumb line. It’s from where you are to where you’re going. And, it’s so important to be able to pick up and forget all that and say, “Okay, play it where it lays.” This is the new situation.

How do you deal with resistance, with criticism, with controversy?

J. Carter Brown: Well, I have a lot at the moment.

I’ve gone on, stayed on under my other hat as chairman of the Fine Arts Commission. And boy, did we get it at the time of the Vietnam Memorial! I mean, I had Ross Perot in my office pounding the table! I knew that he’d sent in operatives to Iran. I didn’t know what was going to happen to me. He wanted it his way. And, there was great brouhaha about that. Now, we have brouhaha about the World War II Memorial. And, as of just a couple of days ago, that’s all been ripped open again, and we’ve got to go through more of these hearings where a small dissident group has ginned up a lot of complaint. And basically, it’s a resistance to change. There’s a nostalgia about the way things were, everybody thinks they were always that way. They forget that the Mall is a 20th century concept, and the Jefferson Memorial also had people lying down in front of bulldozers. But, it was built in 1941, and we have added and changed the Mall continuously, and this is only going to enhance the great design of the vista between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial. And yet people just want to keep everything the way it is. And fine, sometimes it’s better the way it is. But, we feel that this little Fine Arts Commission — which are chosen to have some kind of credentials in the visual world — has a lot of experience in visualizing what something’s going to be. And, we think it’s going to be okay.