I'm still astonished that somebody would offer me a job and pay me to do what I wanted to do. And to this day, that's been the astonishment of my life, and the wonder of my life...I like to work with the tools of my trade. The tools of my trade is a lot of paper and a pencil, and that's all it is.

Chuck Jones was born in Spokane, Washington. He moved with his family to Southern California when he was only six months old. The family moved often, living at various times in Hollywood and Newport Beach. In Hollywood, the young boy was able to observe the still-young film industry. He remembers peering over the studio fence to watch Charlie Chaplin at work on his silent comedies.

Mr. and Mrs. Jones encouraged the artistic leanings of their children, all of whom grew up to be professional artists. At age 15, Chuck dropped out of high school, at his father’s suggestion, to attend Chouinard Art Institute (now known as California Institute of the Arts).

Emerging from school in the depths of the Depression, the young artist found work in the fledgling animation industry, working in succession with Ub Iwerks (Walt Disney’s original partner), Charles Mintz and Walter Lantz (creator of Woody Woodpecker). He advanced from washing cells to in-betweening, finally landing a job at Leon Schlesinger Productions, the supplier of cartoons to Warner Bothers. Chuck Jones was to continue this association for the next 30 years.

In this company he worked for the great animation directors Friz Freleng, Frank Tashlin and Tex Avery, men he credits with teaching him the comic timing, vivid characterization and jubilant anarchy for which Warner Brothers cartoons were famous. He advanced to animator, working on Bugs Bunny and some of the earliest Daffy Duck cartoons. At last, he was promoted to animation director. His trademarks include highly stylized backgrounds and a slew of hilarious characters. His own creations include Pepé Le Pew and, most famously, Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote.

The first Road Runner cartoon was conceived as a parody of the mindless chase cartoons popular at the time, but audiences around the world embraced the series. In the 1940s and ’50s he directed some of the most durable and hilarious animated shorts, including What’s Opera, Doc? and Duck Dodgers in the 24-1/2th Century. In 1950, two cartoons produced by Chuck Jones’s unit won Academy Awards, “For Scent-imental Reasons” (with Pepé Le Pew) and an animated short (“So Much for So Little”), which won in the documentary category, the only cartoon film ever to do so.

In the 1960s, Jones produced Tom ‘n’ Jerry cartoons for MGM, and The Pogo Family Birthday Special for television. In 1962, in the waning days of the theatrical cartoon business, Jones loosened his ties to Warner Brothers and wrote an original screenplay for a UPA animated feature, Gay Purr-ee, which featured the voices of Judy Garland, Robert Goulet and other stars of the day. Jones collaborated with Theodor Geisel (a.k.a. “Dr. Seuss”) on a pair of cartoon specials for television, Horton Hears a Who and The Grinch Stole Christmas. The latter has become a holiday classic. Both won Peabody Awards for Television Programming Excellence. Chuck Jones won another Academy Award in 1965 for the animated short The Dot and the Line, based on a book by Norton Juster. He also produced, co-wrote and co-directed a feature film based on Juster’s children’s classic, The Phantom Tollbooth.

Under the banner of his own production company, Chuck Jones Enterprises, he produced, wrote and directed nine half-hour primetime television specials: The Cricket in Times Square, A Very Merry Cricket, Yankee Doodle Cricket, Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, Mowgli’s Brothers, The White Seal, Carnival of the Animals, A Connecticut Rabbit in King Arthur’s Court, The Great Santa Claus Caper and The Pumpkin Who Couldn’t Smile.

His books include his autobiography, Chuck Amuck; a children’s book, William, the Backwards Skunk; and How to Draw from the Fun Side of Your Brain.

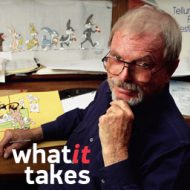

Chuck Jones made more than 300 animated films in a career that spanned over 60 years. In 1996, he received an Honorary Academy Award for Lifetime Achievement for his work in the animation industry. In February 2002, he died at the age of 89, leaving behind a legacy of comic brilliance that will live on forever.

“I’m still astonished that somebody would offer me a job and pay me to do what I wanted to do.”

From the early 1930s, films studios found it well worthwhile to pay Chuck Jones to do what he loved, and millions around the world have laughed themselves sore at Jones’s work with Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Elmer Fudd, Porky Pig, Pepé Le Pew, the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote.

In 1931, Chuck Jones was a penniless art school graduate, struggling to hang on to the lowest rung in the fledgling animation industry. He worked at first as a cel washer, diligently scrubbing transparencies clean of the art that collectors pay thousands of dollars for today. Jones bounced from studio to studio, until at last he found a niche working on the Merrie Melodies series of cartoons for Warner Brothers. At Warner Brothers, he advanced from “in-between” artist to animator and director, creating some of the most memorable cartoons and characters of all time, and collecting an armload of Academy Awards in the process.

Through his diligence, superb draftsmanship, brilliant comic timing and resolute dedication to the highest standards of excellence, Chuck Jones became a legend in the field of animated cartoons, a medium he raised to the level of delirious, side-splitting, fine art.

What got you started on this career path? Were you a good student?

I got good grades in things that I liked, and the people that I encountered, the characters I encountered, as with books. But I didn’t get along with the things that I didn’t. Finally, when I was about to enter my junior year, my father took me out and put me in art school. He figured that I’d probably had enough general education, but I needed to learn how to do something, he didn’t know what. There was a fine arts school there called the Chouinard Art Institute, which is now called the California Institute of the Arts. They have a fine animation division there now, probably the best in the world, which is a curious thing because, a lot of the young people that went to Chouinard Art Institute became the backbone of the animators that made the pictures which followed in due time. So in that sense, and really in only that sense, did my father lead me. He didn’t lead me into cartoons, he led me into learning how to draw in a practical way and not just drawing anything you wanted to.

I would say my mother had more to do with my education as an artist, if you want to call me that, than anything else. All of us drew, and all of us went into different fields of graphics. My sister is a fine sculptress, and my other sister taught painting. My brother is still a very fine painter, and a photographer. All of us went into it. Why? Because we weren’t afraid to go into it.

My mother said — and I didn’t realize how well it works — when I’d bring a drawing to her, she said, “I don’t look at the drawing. I looked at the child, and if the child was excited, I got excited.” And then we could discuss it. Because we were bringing something that meant something to me as a child. And so she would join in my lassitude, or my excitement, or my frustration. She wasn’t a psychologist, but she did understand this simple matter. Also, it accomplishes the only thing that has any meaning to a little child. The only thing an adult can give a child is time. That’s all, there isn’t anything else. That’s the only thing they need, really, is time. If you give them time, you’ll have to be understanding of them and give them time.

How did you get started in the animation business?

Chuck Jones: I went through art school and I came out of there. This was in 1931, and it was right in the Depression — the Depression hit in ’29 — two years before Franklin Roosevelt came in. The whole United States was flat. To expect to get a job when probably three out of every ten people were unemployed was ridiculous. Particularly a kid coming out without experience in anything. To a certain extent I worked my way through art school by being a janitor.

When I came out, one of my friends who had been at Chouinard with me had gone to work with Walt Disney’s ex-partner, a man by the peculiar name of Ub Iwerks. He was the one who animated most of the Disney stuff. Disney was not a good animator. He didn’t draw well at all, but he was a great idea man — always was — and a good writer. Iwerks was a great artist and a great animator. Somebody convinced him that he was the brains in the outfit, and the talent, so he left. Anyway, he was hiring people, and he hired this friend of mine named Fred Kopietz. Fred called me up and asked me if I wanted to go to work. So to my extreme astonishment — which has held for 63 years…

I’m still astonished that somebody would offer me a job and pay me to do what I wanted to do. And to this day, that’s been the astonishment of my life, and delight of my life, and the wonder of my life, and the puzzlement that anybody would be so stupid as to be willing to do that. I hear all these success stories of people, these captains of industry, these forgers of the world, and empire builders and so on. And they talk about all the money they’ve made and become presidents and all that, and I thought, jeez, but look at me. When I was offered a chance to be head of studios I wouldn’t take it. I like to work with the tools of my trade. The tools of my trade is a lot of paper and a pencil, and that’s all it is.

What was your first job in the animated cartoon business?

Chuck Jones: I started out as what they call a cel washer. The celluloids that the paintings eventually end up — that go into the camera in animated cartoons — which is simply the character inked in black, and then the opposing side of the celluloid you put the color. So the ink lines are on one side and the color is on the other. So, in those days — of course there wasn’t color, these were black and white — but they were made the same way. But those cels — and they were really celluloid in those days — they cost seven cents a piece. And so it seemed foolish… After you finished a picture and you used these 3- or 4,000 drawings that were used in those simple days in a seven- or eight-minute cartoon, afterward you washed them off and used them again. If you had a couple of those — two of those — particularly Mickey Mouse! One of those black and white Mickey Mouses recently sold at auction in New York for $175,000. And they were washing them off too! It’s ridiculous. But it’s just a question of nobody thought to save any of them. And why should they? They weren’t worth anything. So that was my first job, was washing them off. And then I moved up to become a painter — black and white, some color. And then I went up to become an inker, which is when you take an animator’s drawings and traced them on to the celluloid. And then I became what they call an in-betweener, which is the guy that does the drawing between the drawings the animator makes.

You bounced around a good deal in the early years, from one place to another.

Chuck Jones: Yeah, for about a year. I worked for Charles Mintz Studio, and then I worked for Walt Lantz, who later on did Woody Woodpecker.

When did you go to work for Leon Schlesinger and Warner Brothers?

Chuck Jones: In 1933 I went to work for Leon Schlesinger and that’s where I stayed for 38 years. Leon had formed a company called Pacific Art and Title. To this day that company exists. It does a lot of the title work for various studios and independent producers. Leon looked very much like an old-fashioned song-and-dance man, but he was a little old for that kind of thing. He was the kind of guy that wore pointy toes — pointies. Unfortunately, he was very lazy. All he knew was he made pictures that Warner Brothers bought. I think he was married to one of Warner’s sisters or something; there was a familial relationship of some kind there. He made pictures and sold them to Warner Brothers. And he didn’t care. As long as they bought them, that was fine.

Tell us a little bit about how Leon Schlesinger became one of the prime inspirations for Daffy Duck.

Chuck Jones: Well, Leon Schlesinger was very lazy, and that stood to our advantage because he didn’t hang over us or anything. He spent as little time in the studio as he could. He’d come back and ask us what we were working on, and we knew he wasn’t going to listen, no matter what we said. So we would say something like, “Well, I’m working on this picture with Daffy Duck, and it turns out that Daffy isn’t a duck at all, he’s a transvestite chicken.” And he would say, “That’s it, boys. Put in lots of jokes.” He had a little lisp. He said, “I’m off to the ratheth.” And so he’d go charging out. And if you don’t know what a “rathe” is, it’s where “horthes” run. So one day, when he went out, Tex (Avery) was directing and I was animating at that time, Bob Clampett was animating too, and Cal Howard, one of our writers, said, “Tex,” he said, “You know that voice of Leon’s would make a good voice for Daffy Duck.”

So he called in Mel Blanc and said, “Can you do Leon Schlesinger’s voice?” And Mel said, “Sure, it’s very simple.” And he said, “How much do you want me to do?” Okay, so they recorded all the voices and everything. The one thing we forgot was that Leon was going to have to see that picture, and hear his own voice coming out of that duck.

Did you think you’d be fired?

Chuck Jones: Oh yes. I expected to be fired. In fact, we all wrote our resignations, all of us that worked on the film. We figured we’d resign before we got fired. Fortunately, we didn’t send them in. Leon came crashing in that day, as he usually did, and we assembled all the troops to watch the picture.

Leon jumped up on his platform and said, “Roll the garbage.” That’s what he always said. It made you feel like he really cared. So we rolled the garbage, and of course everybody in the studio knew the drama of the situation, so nobody laughed. He didn’t care, he didn’t pay attention to what anybody else did anyway. It was only his opinion that counted. So at the end of the picture there was this deathly silence. You could hear crickets, and a horse neighing, like they do in westerns. Way out in the distance, a dog would be wailing. But old Leon jumped up and glared around, and we thought, “Here comes the old axe.” And he said, “Jesus Christ, that’s a funny voice! Where’d you get that voice?” So that was what it was, and he went to his unjust desserts, doubtless taking his money with him. But the voice lives on. As long as Daffy Duck is alive, Leon Schlesinger is there, in his corner of heaven.

We often ask people that we interview: “What person inspired you the most?” But in your case, we’ve heard there was a cat.

Chuck Jones: Well, there was a cat by the unlikely name of Johnson, the only cat I’ve ever known who had a last name for a first. I don’t know whether it was his first name or his last name. We were living in Newport Beach, California. This was around 1918; I was 6 years old. And my brother and I saw this cat… he came to visit us…take up residence, rather, as cats do. It was early in the morning, and my brother and I saw this cat come strolling over the sand dunes. He had scar tissue on his chest, and one ear was slightly bent. He had a piece of string tied around his neck, and an old tongue depressor, and in lavender ink it said “Johnson,” with crude lettering. We didn’t know whether that was his blood type, or his name, or his former owner’s name, or anything. So we called him Johnson. He answered to that as well as anything else. Like most cats, he answered to food, that’s what he answered to. It’s important to me, because it established once and for all in my mind that every cat is different than other cats. Anyway, he came to live with us, and he turned out to be a rather spectacularly different cat.

He came up to my mother while she was finishing breakfast and she figured he wanted something to eat. We’d already explained that he probably was going to stay with us a while. So she offered him a piece of bacon, and piece of egg white, and a piece of toast, all of which he spurned. He obviously had nothing like that in mind. Finally, in a little spurt of whimsy, which was typical of my mother, she gave him a half a grapefruit, and it electrified him. It was like he’d taken a hypodermic. Suddenly, there was this flash of tortoise shell cat whirling around with this thing. Then he came sliding out of it and the thing slowly came to a stop. The whole thing was completely cleaned out and we looked at him in astonishment. There must have been some juice that goes through cats that was lacking in old Johnson, because he loved grapefruit more than anything else in the whole world.

He’d eat it until all the inside was gone. Sometimes he’d eat it in such a way that he ended up wearing a little space helmet, which is really the whole grapefruit, with a flap hanging down on one side like a batter’s helmet. But when he had it on, he seemed to like it, and that was long before anybody ever heard of space helmets. And sometimes he’d walk out on the beach with this thing on his head. If it really bothered him, then he’d kick it off. He liked to be with people, particularly young people. He was very fond of children. We’d all learned to swim early, and…

One day we were swimming and we looked around and here was Johnson out there swimming with us. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen a cat swim or not. They can swim very well, but most of them don’t seem to like it. He really did, but only his eyes would show above the water. He looked like a pug-nosed alligator with hair. For some reason they grimace like this, and his teeth were hanging down, and most of him was under water. All the oil comes off the fur and trails behind them, along with a few sea gull feathers and other stuff. When he got tired out there, he would come and put his arms up on our shoulders and sort of hang there for a while. It was all right as long as it was only people in the family. But unfortunately, it wasn’t always, because if he couldn’t find one of us, he’d approach a stranger. People would come out of the surf with their face going… and you knew they’d had a social encounter with old Johnson out there. They always looked pretty disturbed.

At any rate, the great moment for Johnson came one time when he had eaten his grapefruit and it was stuck on his head, and he came out and strolled down the beach. We were up on the porch of our house, a two-story house, looking down at the sand. And he started off toward the pier, and as it happened, the Young Women’s Christian Association were having a picnic there. Well, not only did he have his helmet on, but somewhere along the line he had found parts of a dead sea gull and it had left a few feathers on his shoulders. So he was quite a sight. He strolled down to where these girls were having a picnic. And they took one look at this thing with the feathers, and the whole business, so they screamed, and jumped up and ran into the ocean. Well, that was a technical mistake, because of course, Johnson, being a gregarious sort, decided that he wanted to join the group. I don’t know, maybe he was going to appeal to the Supreme Court that male cats weren’t allowed in the Girl Scouts, or whatever it was. So he went in after them and they left in various states of undress — not undress, I mean their minds were boggled. And I never saw so many girls that were so boggled. And they never came back to Balboa, or Newport Beach.