It’s very tedious work and you go through tens of thousands of star images. I came to one place where it actually was, turned to the next field, there it was. Instantly, I knew I had a planet beyond the orbit of Neptune. That was the most instantaneous thrill you can imagine. It just electrified me!

Clyde W. Tombaugh was born in 1906 in Streator, Illinois. He attended high school in Streator and moved with his family to a farm in Western Kansas, where a hailstorm destroyed the family’s crops, dashing his hopes of attending college. Tombaugh continued to study on his own, teaching himself solid geometry and trigonometry.

In 1926, at the age of 20, Tombaugh built his first telescope. Dissatisfied with the result, he determined to master optics, and built two more telescopes in the next two years, grinding his own lenses and mirrors, and further honing his skills.

Using these homemade telescopes, he made drawings of the planets Mars and Jupiter and sent them to Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. The astronomers at Lowell were so impressed with the young amateur’s powers of observation, they invited him to work at the observatory.

Clyde Tombaugh stayed at Lowell Observatory for the next 14 years. The young astronomer earned a permanent place in the history of science when he discovered the planet Pluto on February 18, 1930. Pluto’s orbit lies three billion miles from the sun; it takes Pluto two and a half earthly centuries to complete a single orbit around the sun. Seen from Pluto, the sun appears merely as one bright star among many. Pluto’s moon, Charon, is nearly half the size of the planet itself and orbits Pluto once every 6.4 Earth days. From Pluto, Charon appears eight times larger than our moon appears from Earth.

In 1932, Tombaugh entered the University of Kansas, where he earned his bachelor of science degree in 1936. He continued to work at Lowell Observatory during the summers, and after graduation, he returned to work at the observatory full-time. In 1938, he received his master’s degree from the University of Kansas.

During his years at Lowell Observatory, Tombaugh discovered hundreds of new variable stars, hundreds of new asteroids, and two comets. He found new star clusters and clusters of galaxies, including one supercluster of galaxies. In all, he counted over 29,000 galaxies. Tombaugh remained at Lowell until he was called to service during World War II. The astronomer taught navigation to the U.S. Navy at Arizona State College in Flagstaff from 1943 to 1945.

After the war, Lowell Observatory was unable to rehire Tombaugh due to a funding shortfall, so in 1946, he returned to work for the military at the ballistics research laboratories of the White Sands Missile Range in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where he supervised the optical instrumentation used in testing new missiles.

In the course of this work, Tombaugh designed many new instruments, including a super camera called the IGOR (Intercept Ground Optical Recorder), which remained in use at White Sands for 30 years before it was finally improved upon.

After nine years at White Sands, Tombaugh left the missile range in 1955. He was awarded the medal of the Pioneers of White Sands Missile Range.

From 1955 until his retirement in 1973, Clyde Tombaugh was on the faculty at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces. In later years, Tombaugh crisscrossed the United States and Canada, giving lectures to raise money for New Mexico State University’s Tombaugh scholarship fund for postdoctoral students in astronomy. He died at home in Las Cruces, shortly before his 91st birthday.

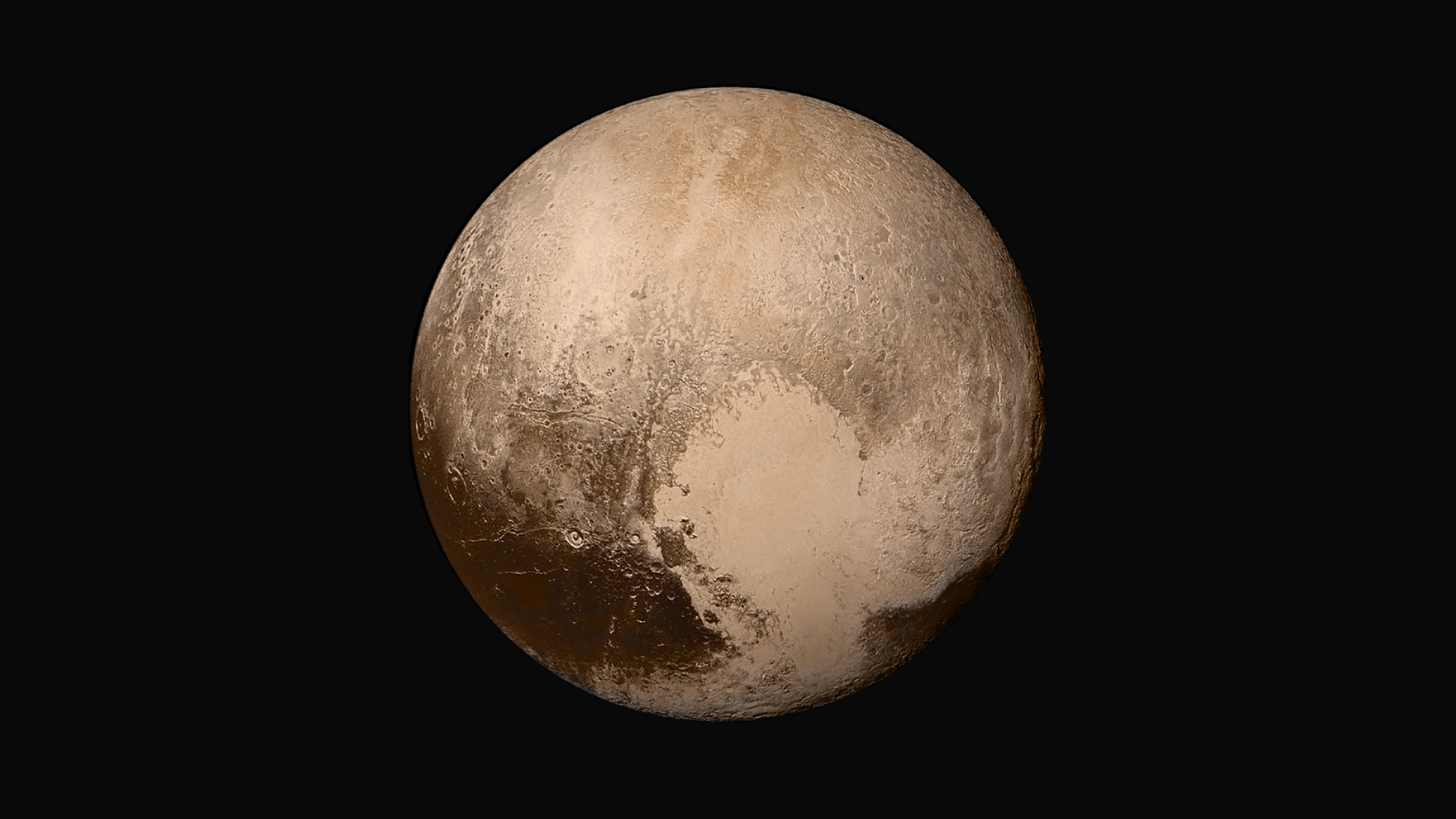

In recent years, a host of objects have been discovered circling the sun in the “Kuiper Belt,” a vast archipelago that extends billions of miles from a point between Neptune and Pluto. One, known as 2003 UB313, or Xena, is close to Pluto in size. Four others, all smaller than Pluto, have been discovered since 2002. For several years, the world’s astronomers debated whether these bodies should also be recognized as planets. In a highly controversial decision, the International Astronomic Union (IAU) voted in 2006 to redefine the word “planet” and to classify Pluto, Xena, and the newly discovered smaller bodies as “dwarf planets.” Thousands of objects comparable to these “dwarf planets” may yet be discovered, but many astronomers and members of the general public resisted the reclassification of Pluto and questioned the criteria cited as the basis of the IAU decision.

When the NASA space probe New Horizon flew by Pluto in 2015, it revealed that Pluto is a highly complex world, with dunes and mountain peaks of solid frozen methane and the possibility of a vast liquid sea beneath the ice. These discoveries intensified debate over the definition of planets and the status of Pluto.

When New Horizon took flight for the outer reaches of the solar system, it carried an ounce of Tombaugh’s ashes, bringing a trace of Clyde Tombaugh’s mortal self to the new world he discovered, beyond the frontier he opened for all mankind.

October 26, 1991: Clyde W. Tombaugh in the backyard of his home in Las Cruces, New Mexico, with his homemade telescopes, including the 9-inch Newtonian reflector he built in 1928 at the family farm in Kansas with discarded farm machinery and car parts.

“Now I had figured out beforehand, if there was a Planet X, how I would recognize it if I encountered it.”

When Clyde Tombaugh entered the University of Kansas, he tried to register for freshman astronomy. The professor in charge of the course refused to enroll him. He thought Tombaugh’s presence in the class would be inappropriate since Tombaugh had already achieved something only a handful of astronomers have ever done. As a 24-year-old research assistant at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, without the benefit of any formal training in astronomy, Tombaugh had discovered a new planet: Pluto.

Clyde Tombaugh’s interest in astronomy began when he was a young boy, growing up on a farm in the Midwest, without access to observatories, universities, or even a large library. Unable to afford a college education, Tombaugh taught himself solid geometry and trigonometry and studied the stars through telescopes he built himself.

After his discovery of Pluto won him world renown, Tombaugh at last acquired the college education he had long desired. He resumed astronomical research for the Lowell Observatory, taught navigation to the U.S. military during World War II, and after the war, used his expertise in optics to assist the military in the development of missiles at White Sands Missile Range.

Long into his retirement, Clyde Tombaugh continued to enjoy stargazing from the telescopes in his own backyard. Although the discovery of more objects in the Kuiper Belt beyond Neptune has caused astronomers to reconsider the formal definition of a planet, the significance of Tombaugh’s discovery has grown with the years. Clyde Tombaugh discovered much more than a single planet — he opened a door to the outer reaches of our solar system.

Let’s begin at the beginning. How did you first know what you wanted to do in your life?

Clyde Tombaugh: When I was in the fourth grade, I became intensely interested in geography, and I learned it well. And in fact, by the time I was in sixth grade, I could bound every country in the world from memory. By then, the thought occurred to me, “What would the geography be like on the other planets?” So that was my natural entrance into astronomy, you see. So I’ve been interested in that particular area ever since. Of course, I took all the science and math that was offered in high school, and I had an uncle in Illinois who lived about nine miles from us, and he was an amateur astronomer, and he had a three-inch telescope. So the views with that telescope were my first views of the rings of Saturn, and Jupiter’s moons, and the craters on the moon.

What event inspired you in this field as a young person?

Clyde Tombaugh: I was interested in eclipses when they occurred, things like that. And then later, my uncle and my father invested in a Sears Roebuck better-grade telescope, which I used thousands of times to look at objects in the sky I had read about. That was always a thrill, to find them in the sky. I was interested in telescopes and the way they worked, and so on, because I had an intense desire to see what the things looked like. So I learned how to use telescopes and find things in the sky. Although my early equipment was very modest, later I made my own, and they were more powerful.

How old were you when you built your first telescope?

Clyde Tombaugh: That was in 1926. I was 20.

Can you tell us about the first telescope you built yourself?

Clyde Tombaugh: It wasn’t a very good one because it had such meager instructions. It worked fairly well but not good enough to suit me. So the following year, the Scientific American published a book called Amateur Telescope Making. I bought a copy, and I digested it, and I realized where I’d made mistakes. So the next telescopes were much better because they had the benefit of more information. The nine-inch, for instance, in my backyard — you probably saw it there — was the third telescope of excellent quality. It was the drawings I made of the markings on Mars and Jupiter with that telescope, that I sent to the Lowell Observatory in 1928, that impressed them favorably so that they invited me to come out for a trial work with the new telescope at Flagstaff. So that was a big break.

Let’s talk about that time in your life. How did you come to send your drawings to the Lowell Observatory?

Clyde Tombaugh: What you do is, you have your drawing board and a pencil with you in hand at the telescope, and you look in and you make some markings on the paper. And you look in again, back and forth, many, many times, so as to get the stuff in the right proportion, the right intensity. It takes about a half-hour to make a good drawing that way. And when the temperature is freezing, it’s a bit hard on your fingers, but I was interested in putting down what I saw. And that’s what paid off.

As an amateur, what made you so confident that your drawings had some significance?

Clyde Tombaugh: At that time, the Lowell Observatory was the only planetary observatory in the country, and I was particularly interested in planets at that time, so I thought I would just like to see what they think of them. Of course, the planets are never the same twice; they’re always different. And so they could see from my drawings — they could compare the markings I had drawn with their current photographs, and they knew that I was drawing what I was really seeing, and it wasn’t copied from somewhere. So they realized that I was careful, I saw well, and so on, and so they thought I would be a good candidate to run this new photographic telescope they were installing.

Can we relive that experience of when you first realized you had discovered an unknown planet?

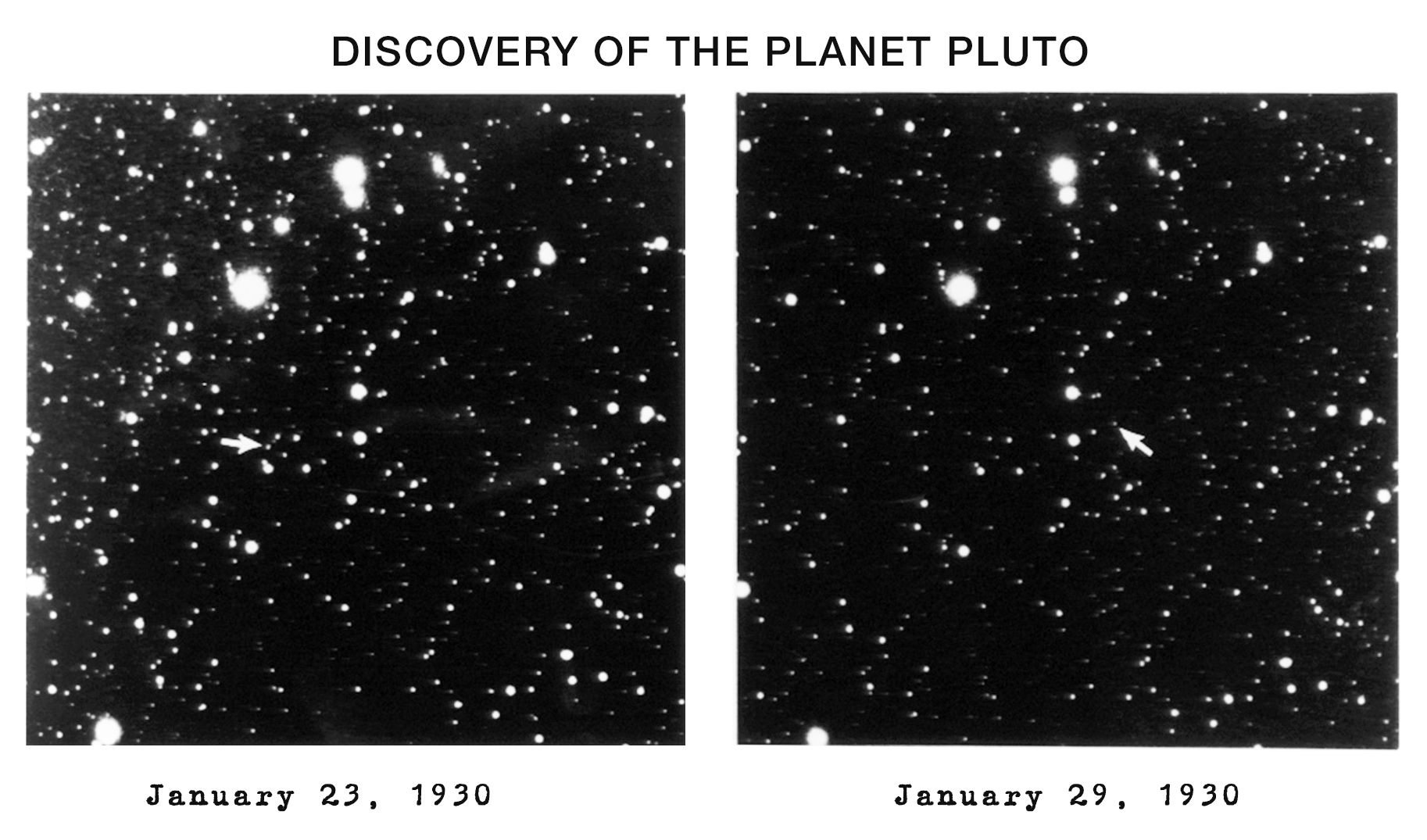

Clyde Tombaugh: I was assigned to taking photographs at night with the telescope. It was a wide-angle photographic telescope with a one-hour exposure. Then I developed the plates, and so on, and a few days later, I would put them on a special machine called the Blink Comparator, where you compared two plates rapidly in alternating views to see if any change occurred on the starfield from one plate to the other made a few nights later. That was the technique because these plates would have several hundred thousand star images a piece — and if you don’t think that’s an awesome thing to look at and realize you had to see all those images — which one moved, you see. So the challenge there was far more difficult than most people ever realized.

But I had some soul-searching questions of myself. Do I want to go through this very tedious job or not? But I didn’t want to go back to the farm to pitch hay, and I knew that they’d hired me to do this job, so either I do this job or go back to the farm. So I went through some pretty tedious hardship cases to accomplish this, but I was dedicated, and I liked the work, really, and I was very, very careful. All the suspects were checked with a third plate, did the job very thoroughly, and it paid off. That’s where others failed because they were not careful enough. Their strategy was not good, and I had thought this thing out very carefully in my own mind of how to do this, you see, and it worked.

At the time you discovered Pluto, there was a lot of talk about what they called “Planet X.” What did they mean by “Planet X”?

Clyde Tombaugh: Percival Lowell interpreted some of the — what they call “residuals” — slight irregularities in the orbit of Uranus, particularly, and later Neptune, as indicative of a mass out there as yet unseen — like the case of Neptune being discovered mathematically before it was seen, you see. These residuals were very, very small. In fact, so small that they were questionable whether they were real or not, but it was the best that he had. So he predicted that there was a planet out there about seven times more massive than the earth, beyond the orbit of Neptune. Of course, Pluto does not have that much mass.

When did you see it?

Clyde Tombaugh: It was daytime when I did the scanning. When I took the photographs, I had no idea that Pluto’s image was on those plates. Not until I began to scan them carefully sometime later — in fact, it was several weeks later when I got to that pair — and I encountered, as going through all these alternating views of starfields, and here’s one that shifted position by the right amount. Now I had figured out beforehand that if there was Planet X, how I would recognize it if I encountered it, you see. So I thought all this out beforehand. And so when it came, there it was, and instantly, I realized I had found a planet beyond the orbit of Neptune by the amount of shift. I knew the scale of the plates, I knew the interval, and it was just a matter of geometry.

I had taken the plates of the telescope the previous month, in January 1930, and I did not know that I had recorded the image of Pluto on those plates, not until I scanned them later, in February. And so you passed your gaze over all these stars — you have to be conscious of seeing every star image because you don’t know which one’s going to shift, if they shift. So it’s very tedious work, and you go through tens of thousands of star images. Well, I came to one place where it actually was, turned to the next field, there it was. Instantly, I knew I had a planet beyond the orbit of Neptune because I knew the amount of shift was what fit the situation, and that was the most instantaneous thrill you can imagine. It just electrified me!

It was an intense thrill. It made my day! That was the 18th of February 1930, about four o’clock in the afternoon. I realized, in a few seconds’ flash, that I’d made a great discovery, that I’d become famous, and I didn’t know what would happen after that. So it was a very intense thrill. You don’t have that kind of a thrill very often!

At first, I had a little sense of caution. I thought I’d better check this with a third plate, which is another date, to see if there’s an image there in the right place that would be consistent with the images on the other plates. That was the final proof. Sure enough, it was there. That was when I was 100 percent sure.

That’s when I notified the assistant director, Dr. Lampland, and he came in and looked, and then I went down and told the director, Dr. Slipher — Vesto Slipher. At that time, Dr. Slipher’s brother, Earl (E. C. Slipher) was in Phoenix serving as a senator in the state legislature of Arizona, so he wasn’t there at the time. Of course, it electrified them, too.

I told the assistant director across the hall from me. This machine makes a clicking noise that could be heard in that part of the building. His office was across the hall, and he understood the blinking business, too. He had been involved in some of the earlier searches. He said, “I heard the clicking suddenly stop and a long silence,” and he surmised I had run onto something, so I was checking out the third plate and all that kind of thing, and here this poor man was sitting at his desk in terrible suspense, waiting to be invited in for a look. I didn’t know about that until he told me that later. Well, I showed him the plates, the dates and all — that everything seemed to be consistent with putting the object beyond the orbit of Neptune. And then, I went down and told the director. He came up and looked and saw. So the Lowell Observatory was changed from that day on!

They realized they really had a prize. And, of course, they probably felt a little bit strange, especially V. M. Slipher, because he had gone through the platal field and missed Pluto one year earlier — missed it on the plates. He was doing blinking. He wanted to be the one to find Pluto, and he failed. So, I suppose, he probably felt a little chagrined, but he realized and knew that I had something because the aspects were very convincing. So then they got in touch with the observatory trustee who was living in Massachusetts — he’s Lowell’s nephew — and told him about it. So it was kept secret for a few weeks so we could follow it, and we could learn more about it so we could publish more about it when it came out. Because we knew that when it was announced, there’d be an avalanche — and there was. It exceeded what we expected. So we kept it secret for about three weeks.

How did you name it Pluto?

Clyde Tombaugh: Unfortunately, so many of the Greek gods’ and goddesses’ names had been given to the asteroids beforehand, so there weren’t very many choices left. Pluto seemed to be a good name, so the staff voted on it unanimously to adopt the name of Pluto.

We considered many names, of course, and Pluto was the final selection. It was chosen by the staff of the Lowell Observatory. The Lowell Observatory director proposed this name to the American Astronomical Society and the Royal Astronomical Society of Great Britain — that this name be given to the planet — and both bodies accepted it unanimously. So we knew the name would stick. We realized, in the case of the discovery of Uranus, that the name originally did not stick. We did not want to repeat that mistake, you see. So Pluto has stuck.

Pluto was the god of the lower world, of Hades. Pluto’s out there, far from the sun, where sunlight is the average distance: sunlight’s only one-sixteen-hundredth as bright as on Earth — rather dark. And if you think of Hades as a dimly lit place — or utter darkness — it kind of fits in with some of the characteristics of Pluto, probably, or of Hades. So it seemed fairly appropriate from that standpoint. And then, when the satellite of Pluto was discovered in 1978 by (James) Christy at the Naval Observatory, he named it Charon because his wife’s name was Charlene. Now Charon was the boatman who ferried the souls of the dead across the River Styx to Pluto’s realm of Hades. So the satellite name fits in very well with Pluto, you see. And the name Charon didn’t happen to be used. So that was good mythology there.

So, soon after the discovery, there was some apprehension that maybe this object I’d found was only an interloper and that the real Planet X was yet to be found, so they said they wanted me to go on searching more. So I searched a lot more of the sky and no Planet X ever showed up.