I believe in nonviolence as a way of life, as a way of living.

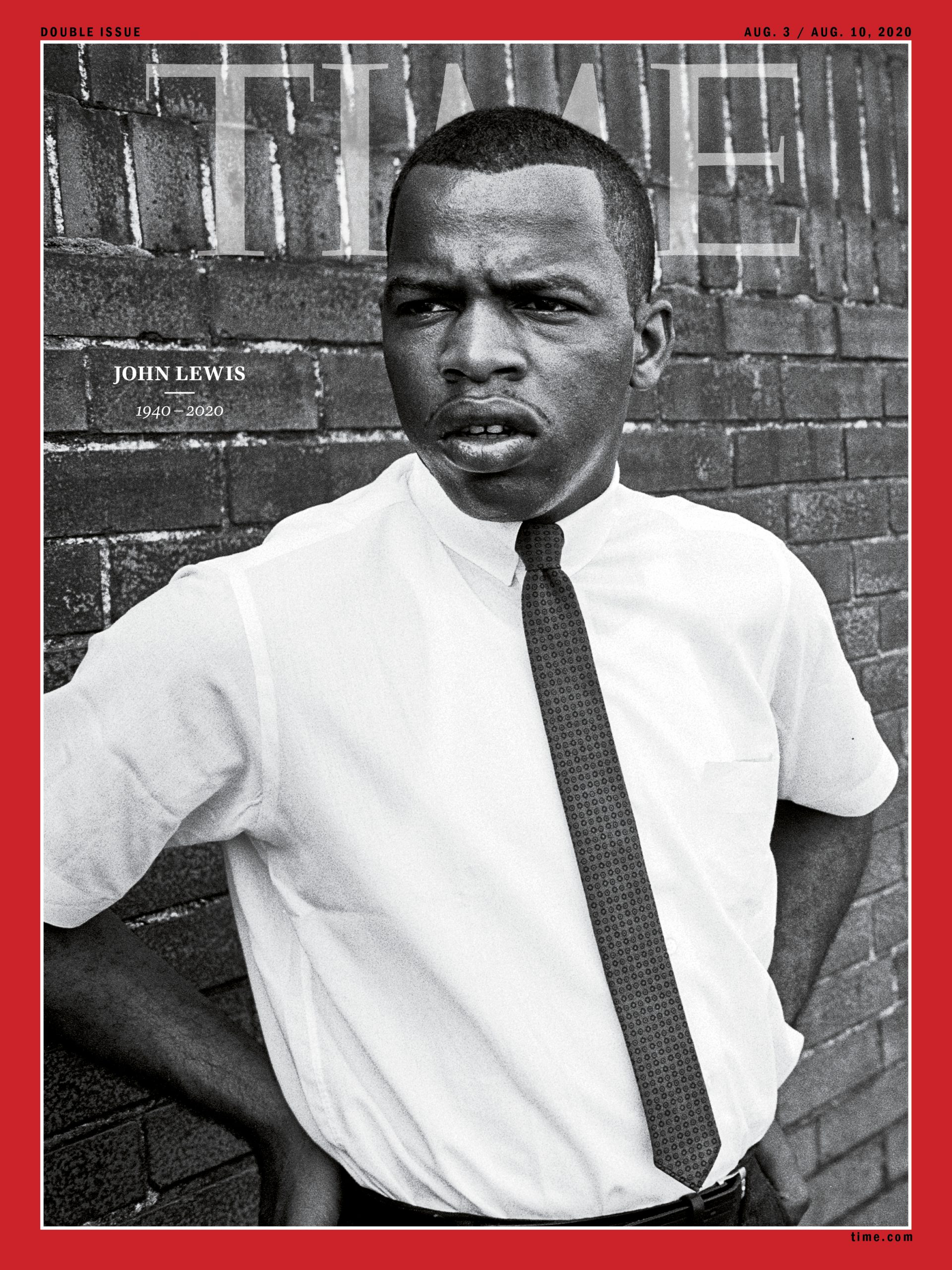

John Lewis was born to a family of sharecroppers outside of Troy, Alabama, at a time when African Americans in the South were subjected to a humiliating segregation in education and all public facilities, and were effectively prevented from voting by systematic discrimination and intimidation.

From an early age, John Lewis was committed to the goal of education for himself, and justice for his people. Inspired by the example of Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the Montgomery bus boycott, he corresponded with Dr. King and resolved to join the struggle for civil rights. After attending segregated public schools in Pike County, Alabama, he graduated from the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee and completed a bachelor’s degree in religion and philosophy at Fisk University.

As a student he made a systematic study of the techniques and philosophy of nonviolence, and with his fellow students prepared thoroughly for their first actions. They began with sit-ins at segregated lunch counters.

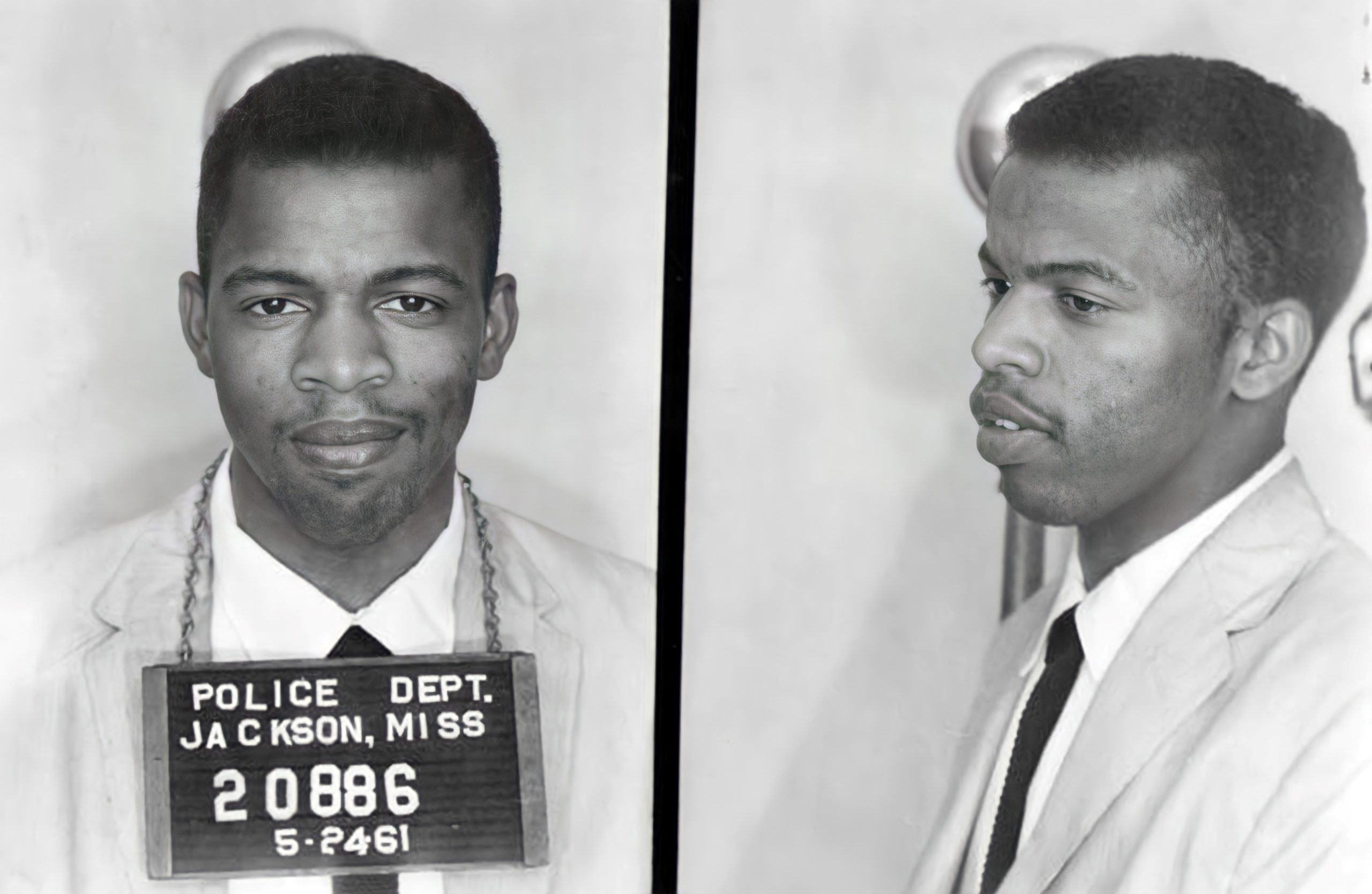

Day after day, Lewis and his fellow students sat silently at lunch counters where they were harassed, spat upon, beaten and finally arrested and held in jail, but they persisted in the sit-ins. In 1961, Lewis joined fellow students on the Freedom Rides, challenging the segregation of interstate buses. In the Montgomery bus terminal, he was again attacked by a mob and brutally beaten.

Lewis was one of the founding members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and served as its president from 1963 to 1966 when SNCC was at the forefront of the student movement for civil rights. By 1963, he was recognized as one of the “Big Six” leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, along with Dr. King, Whitney Young, A. Phillip Randolph, James Farmer and Roy Wilkins. He was one of the planners and keynote speakers of the March on Washington in August 1963, the occasion of Dr. King’s celebrated “I Have a Dream” speech.

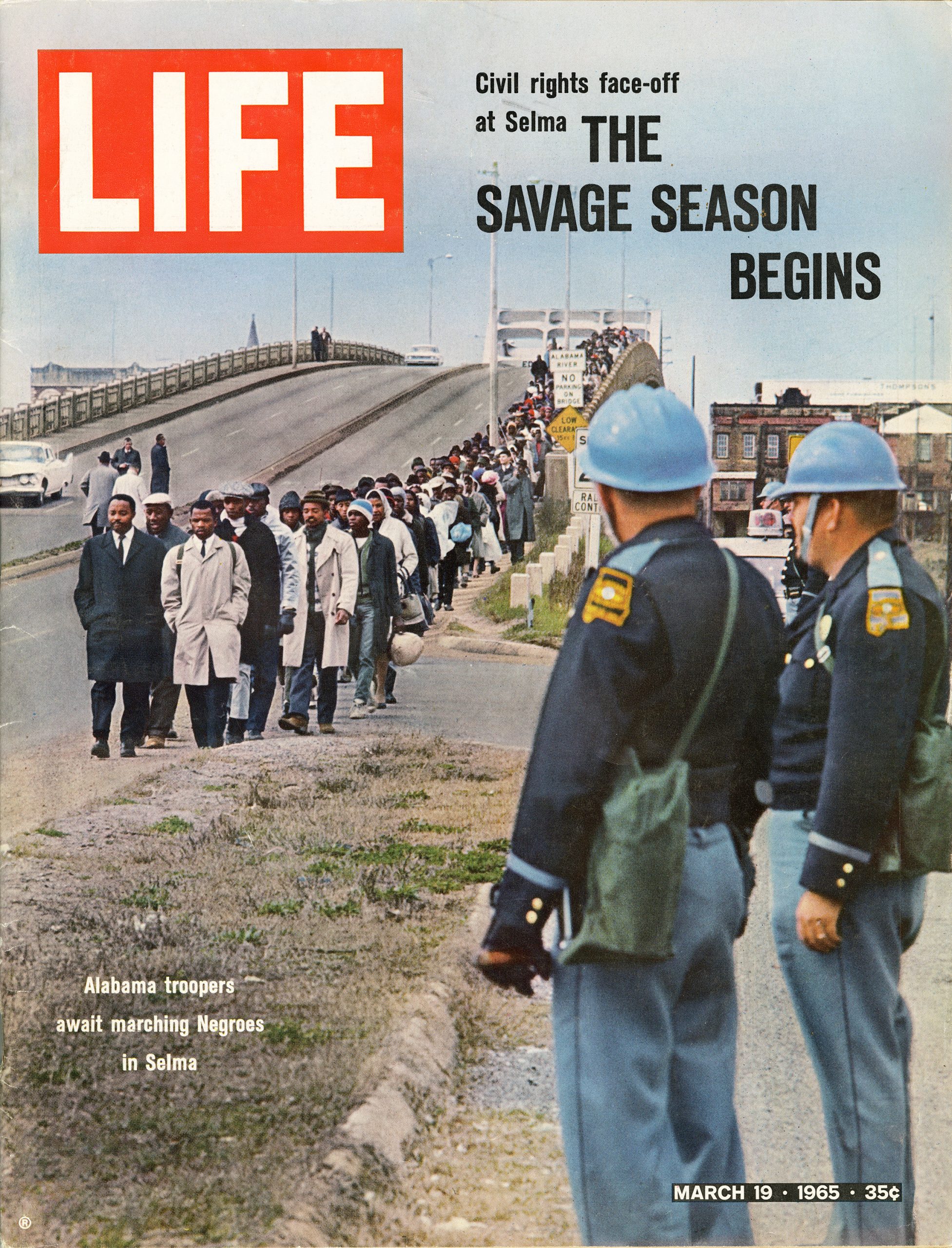

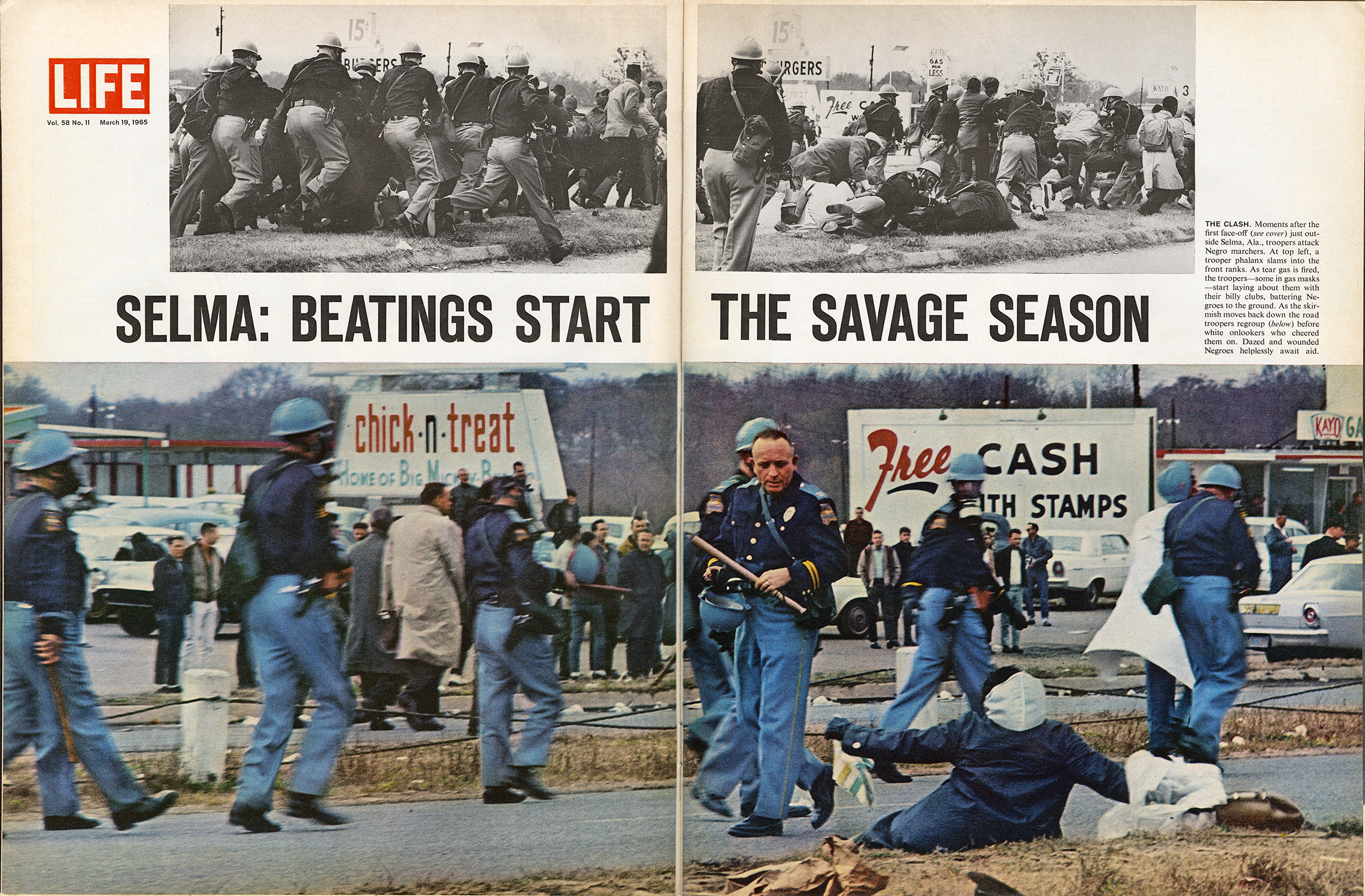

In 1964, Lewis coordinated SNCC’s efforts for “Mississippi Freedom Summer,” a campaign to register black voters across the South. The following year, Lewis led one of the most dramatic protests of the era. On March 7, 1965 — a day that would become known as “Bloody Sunday” — Lewis and fellow activist Hosea Williams led over 600 marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. At the end of the bridge, they were met by Alabama state troopers, who ordered them to disperse. When the marchers stopped to pray, the police discharged tear gas and mounted troopers charged the demonstrators, beating them with nightsticks. Lewis’s skull was fractured, but he escaped across the bridge to a church in Selma. Before he could be taken to the hospital, John Lewis appeared before the television cameras calling on President Johnson to intervene in Alabama.

Scenes of the violence, and of the injured John Lewis, were broadcast around the world, and outraged public opinion demanded that the president take action. Two days later, Dr. King led 1,000 members of the clergy on a second march from Selma to Montgomery, with the eyes of the world watching. A week and a day after Bloody Sunday, President Johnson appeared before a joint session of Congress to demand passage of the Voting Rights Act, empowering the federal government to enforce the voting rights of all Americans. The passage of the voting rights act finally brought the federal government into the struggle, squarely on the side of the disenfranchised voters of the South.

The violent deaths of his friends Martin Luther King, Jr. and Senator Robert Kennedy in 1968 were a great blow to John Lewis, but he remained committed as ever to the philosophy of nonviolence. As Director of the Voter Education Project (VEP), he helped bring nearly four million new minority voters into the democratic process. For the first time since Reconstruction, African Americans were running for public office in the South, and winning.

Lewis settled in Atlanta, Georgia, and when the former Governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter, became President, he tapped John Lewis to head the federal volunteer agency, ACTION. In 1981, after Jimmy Carter had left the White House, John Lewis was elected to the Atlanta City Council, where he became an effective advocate of neighborhood preservation and government reform. In 1986 he ran for Congress, and John Lewis, whose own parents had been prevented from voting, who had been denied access to the schools and libraries of his hometown, who had been threatened, jailed and beaten for trying to register voters, was elected to the United States House of Representatives.

From then on, he was re-elected repeatedly by overwhelming margins, on one occasion running unopposed. For more than 30 years, he represented a district encompassing the city of Atlanta and parts of four surrounding counties. Congressman Lewis sat on the House Budget Committee and House Ways and Means Committee, where he served on the Subcommittee on Health. He served as Senior Chief Deputy Democratic Whip, as a member of the Democratic Steering Committee, the Congressional Black Caucus, and the Congressional Committee to Support Writers and Journalists. Apart from his service in Congress, he was Co-Chair of the Faith and Politics Institute.

Congressman Lewis received numerous honorary degrees and awards, including the Martin Luther King, Jr. Nonviolent Peace Prize, the NAACP Spingarn Medal, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Award of the National Education Association, and the John F. Kennedy “Profile in Courage” award for lifetime achievement.

His courage and integrity have won him the admiration of congressional colleagues on both sides of the aisle. Senator John McCain has written a moving tribute to John Lewis in his book Why Courage Matters. Congressman Lewis gives his own account of his experiences in the Civil Rights era in Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement, published in 1998.

Congressman Lewis began the 2008 presidential campaign as a supporter of Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton. His decision to switch his support to Senator Barack Obama was considered a major turning point in the campaign. When Lewis appeared at President Obama’s inauguration, he was the only surviving speaker from the 1963 March on Washington.

In addition to his advocacy of domestic issues, Congressman Lewis took a passionate interest in human rights on the international stage. In 2009, he was arrested, with three other U.S. Representatives, outside the Embassy of Sudan, where they were protesting the obstruction of aid to refugees in Darfur.

The Congressman was an ardent supporter of health insurance reform. In an eerie echo of his past struggles, he was subjected to angry catcalls and abusive language by opponents of the 2010 health care bill as he entered the Capitol for a crucial vote. As in years past, his courage was unwavering, and the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act became one of the proudest achievements of his legislative career. In a ceremony at the White House, President Barack Obama awarded him the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

In the 2018 election, John Lewis was elected to his 16th term in the House of Representatives. In the last days of 2019, Congressman Lewis announced that he had been diagnosed with Stage 4 pancreatic cancer. He resolved to return to Washington for the 2020 session of Congress to continue working while he pursued treatment.

Following this announcement, supporters, admirers and his colleagues in Congress offered prayers, support and tributes to a beloved hero of the struggle for freedom and justice. John Lewis served in Congress until his last days, recording a virtual town hall with former President Obama, and speaking at Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington a month before his death.

“I thought I was going to die a few times. On the Freedom Rides in the year 1961, when I was beaten at the Greyhound bus station in Montgomery, I thought I was going to die. On March 7, 1965, when I was hit in the head with a night stick by a state trooper at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, I thought I was going to die. I thought I saw death, but nothing can make me question the philosophy of nonviolence.”

By age 23, John Lewis was already recognized as one of the principal leaders of the American Civil Rights Movement, along with Martin Luther King, Jr. The son of sharecroppers in rural Alabama, he led his first demonstrations while studying theology in Nashville, Tennessee.

As Chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, he was a leader in many of the most dramatic campaigns of the movement: the lunch counter sit-ins, the Freedom Rides and the March on Washington. He suffered serious injuries from mob violence and personal physical attacks, and would be arrested more than 40 times, but John Lewis would not be dissuaded from the pursuit of justice. In 1965 he led the historic march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. The marchers were attacked by Alabama state troopers, and John Lewis had his skull fractured, but the subsequent march from Selma to Montgomery led directly to the passage of the Voting Rights Act, finally committing the federal government to the enforcement of voting rights for all Americans.

Over the following decades, John Lewis led an explosion of minority voter registration that has transformed American politics. In 1986, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives. For more than 30 years, he has represented the City of Atlanta, Georgia and surrounding counties in Congress, where he remained one of America’s most courageous champions of human rights.

Congressman Lewis, as a student you participated in the lunch counter sit-ins. These were among the first organized acts of civil disobedience protesting segregation. Could you tell us about that?

I’ll tell you, I grew up overnight. By the fall of 1959 we had what we called “test sit-ins” in Nashville. We went through a period of role playing and social drama, and then it came time for a group of black and white college students to go to downtown Nashville and just sit at a lunch counter, to establish the fact that people were denied service. It was in November and December of 1959. And then from a sit-in started in Greensboro, North Carolina, on February the 1st, 1960, we started sitting in on a regular basis. And it was there that, by sitting down, I think we were really standing up. I saw many of us, and I know in my own case I grew up while I was sitting on a lunch counter stool. I became a different person. I became a different human being.

What went through your mind? What was in your head the very first time you sat down at a segregated lunch counter?

John Lewis: Somehow, in some way, I just felt that we were involved in something that was so large, so necessary, so right. It was almost holy. It was something very righteous and something very pure about it. I was sitting there with other young college students. For the most part we were well-dressed, we were orderly, we were peaceful, and we were looking straight ahead, or either we were doing our homework, and people would come up and call us “niggers.” They would come up and spit on us, put lighted cigarettes out in our hair or down our backs, pull us off the lunch counter stool, and we didn’t strike back. At times we would just look straight ahead. I just felt that we had to do what we were doing and that it was necessary.

Weren’t you ever just afraid?

John Lewis: As a participant in the movement, as I was sitting in, I came to that point where I lost all sense of fear.

I will never forget in late February 1960, one morning we were preparing to sit in, and a very influential citizen of Nashville came to the church where we were gathering and said if we go down on this particular day the officials were going to allow people to beat us, to pull us off the lunch counter stools, and then going to arrest us, and, “Maybe you shouldn’t go. Maybe it’s too dangerous.” And we all said we had to go, and we went down. When I was growing up, my mother and father and family members said, “Don’t get in trouble. Don’t get in the way.” I got in trouble. I got in the way. It was necessary trouble. While we were sitting there and we were being pulled off the lunch counter stools and then beaten, the local officials, police officials, the chief of police and others, came up and placed us all under arrest. I was arrested along with 87 other students. The Nashville sit-ins became the first mass arrest in the sit-in movement, and I was taken to jail. I’ll tell you, I felt so liberated. I felt so free. I felt like I had crossed over. I think I said to myself, “What else can you do to me? You beat me. You harassed me. Now you have placed me under arrest. You put us in jail. What’s left? You can kill us.” But as a group, and I know as one person, we were determined to see the end of segregation and racial discrimination in places of public accommodation. So I lost my sense of fear. You know, no one would like to be beaten. No one would like to go to jail. Jail is not a pleasant place. No one liked to suffer pain, but for the common good we were committed.

What did your parents think of all this?

John Lewis: My mother, my father. My mother, my dear mother, she was so worried. She was so troubled. She didn’t know that I was even involved, because I hadn’t had any discussion until she heard that I was in jail, when the school official called and informed her that I was in jail with several other students. The next day or so I got a letter saying, “Get out of the movement. Get out of that mess. You went to school to get an education. You’re going to get yourself hurt. You’re going to get yourself killed.” And I wrote her back and said, “I think I did the right thing. It was the right thing to do.” Years later she became very, very supportive, especially after the Voting Rights Act was passed and she was allowed to become a registered voter.

Did your belief in nonviolence ever waiver? Did you ever question the method?

John Lewis: As a participant, and even today, I have never ever questioned the method, never questioned this idea, this concept of passive resistance. I believe in nonviolence as a way of life, as a way of living. I believe that this idea is one of those immutable principles that is non-negotiable if you’re going to create a world community at peace with itself. You have to accept nonviolence as a way of life, as a way of living. I thought I was going to die a few times. On the Freedom Rides in the year 1961, when I was beaten at the Greyhound bus station in Montgomery, I thought I was going to die. On March 7, 1965, when I was hit in the head with a night stick by a state trooper at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, I thought I was going to die. I thought I saw death, but nothing can make me question the philosophy of nonviolence.

Or want to retaliate?

John Lewis: No, I cannot and will not retaliate. We grew to respect the dignity and the worth of every human being. When we were harassed by Sheriff Clark in Selma or Bull Connor in Birmingham, when I was being beaten by an angry mob in Montgomery, you try to put yourself in the place of the people that are abusing you, and see that person as a human being, and try to do what you can to win that person over, to change that person. In a sense we all were victims, victims of a system.

Let me ask about March 7, known as “Bloody Sunday.” What was going through your mind when you saw the array of state troopers on horseback, and you and Hosea Williams at the front of that line walked into that?

John Lewis: As we started walking across the Alabama River, across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, I really thought that we would be arrested and taken to jail. I was prepared to be arrested, and I was wearing a backpack, and in this backpack I had two books, an apple, an orange, toothbrush and toothpaste. I thought we were going to go to jail. I wanted to have something to read, something to eat, and since I was going to be in jail with my friends, colleagues and neighbors, I wanted to be able to brush my teeth. And we get to the high point, highest point on that bridge. Down below we saw the Alabama state troopers, the Sheriff’s Deputies, members of Sheriff Clark’s posse, and when Major John Claude said, “This is an unlawful march.” I think he said, “I am Major John Claude of the Alabama state troopers. This is an unlawful march. You will not be allowed to continue. I give you three minutes to disperse and return to your church.” And I think Hosea Williams said, “Major, will you give us a moment to pray?” And before we could even get word back, he said, “Troopers advance.” I knew then that we were going to be beaten. And you saw these men putting on their gas masks, and they came towards us beating us with night sticks, pushing us, trampling us with horses, and releasing the tear gas. I became very concerned about the other people in the march, because I thought I was going to die. I just sort of said to myself, “This is it. This is the end of the road for me. I’m going to die right here on this bridge.” And to this day, 39 years later, I don’t know how I made it back across the bridge, through the streets of Selma, back to that little church that we left from, but I do recall being back at that church that Sunday afternoon.

It was Brown Chapel AME Church. When we got back, the church was full to capacity. Several hundred people on the outside were trying to get in to protest what had happened. Someone asked me to say something to the audience, and I stood up and said, “I don’t understand it. President Johnson can send troops to Vietnam but cannot send troops to Selma, Alabama to protect people whose only desire is to register to vote.” The next thing I knew I had been admitted to the Good Samaritan hospital in Selma.

Was that a turning point in the Civil Rights Movement?

John Lewis: I think what happened in Selma was a turning point in the Civil Rights Movement and probably was one of the finest hours in the movement. Because of what happened in Selma, I mean people saw the film footage of what happened on television that Sunday night, that Monday morning. There was a sense of righteous indignation. People didn’t like it. The American people didn’t like it. There were demonstrations in almost every major city in America, on almost every major college campus, at the White House, the Department of Justice, at American embassies abroad. I remember Dr. King coming to visit me that Monday morning in the hospital, and he said, “John, don’t worry. We’ll make it from Selma to Montgomery. The Voting Rights Act will be passed.” And he told me that he was issuing a call for religious leaders to come to Selma the next day, and the next day, that Tuesday, March 9, more than a thousand ministers, priests, rabbis and nuns came to Selma and marched across the bridge to the point where we had been beaten two days earlier.

President Johnson called Governor Wallace to come to the White House to try to get assurance from him that he would be able to protect us if we decided to march again. Wallace could not assure the President. Lyndon Johnson was so moved that he had to do something. The American people were saying, “You must act.” The Congress was saying, “You must do something.” So he went on television, and…

On March 15, 1965, Lyndon Johnson made one of the most meaningful speeches any American president had made in modern times on the whole question of civil rights and voting rights. I was with Dr. King as we watched and listened to Lyndon Johnson the night of March 15. He spoke to the nation. He spoke to a general session of the Congress. He started that speech off that night by saying, “I speak tonight for the dignity of man and for the destiny of democracy.” He went on to say, “At times history and fate meet at a single place in man’s unending search for freedom. So it was more than a century ago at Lexington and at Concord. So it was at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama.” He condemned the violence in Selma, and he mentioned the fact that one good man, a man of God, was killed. Reverend James Reed, a white minister from Boston, had participated in a march on March 9. And then the night of March 9 he went out to try to get something to eat with two or three other white ministers, and they were jumped and beaten by members of the Klan, and a day or so later he died at a local hospital in Birmingham. President Johnson recognized that, but before he closed that speech and introduced the Voting Rights Act, he said, “We shall overcome.” He said it more than once, “And we shall overcome.” And he became the first president to use the theme song of the Civil Rights Movement in a major speech, and Dr. King was so moved he started crying, and we all cried a little when we heard Lyndon Johnson say, “And we shall overcome.”