That's been my sort of aim in life, to never miss an opportunity.

The internationally famed soprano, Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, was born Claire Mary Teresa Rawstron in the small New Zealand seaside town of Gisborne, where Captain James Cook first made landfall. Just at the edge of the international dateline, it prides itself as the first city in the world to greet the sun.

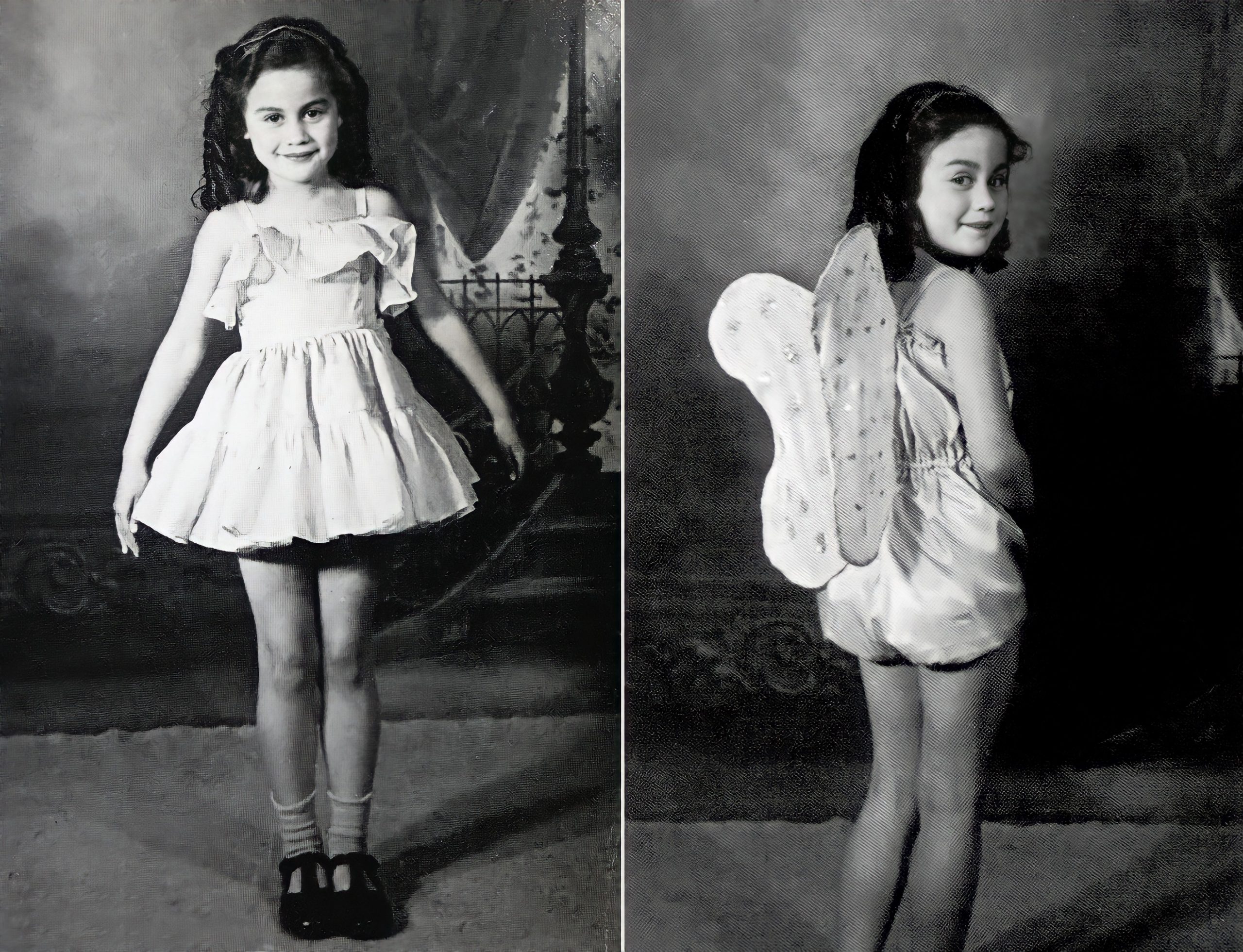

Here, the birth child of a native Maori man and a woman of European extraction was adopted at five weeks of age by a local couple, Tom and Nell Te Kanawa, he also a Maori and she with family ties to the British Isles. The Te Kanawas named their daughter Kiri, the Maori word for bell. She was to be their only child. The family came from modest circumstances: Tom Te Kanawa ran a truck contracting business, while his wife stayed home with Kiri. Some of the soprano’s earliest recollections are of blissfully swimming in the sea with her father and of fishing. On one outing, she nearly drowned when a boat capsized, trapping her underneath, until her father managed to dive down and rescue her. And for almost as long as she can remember, she sang. Her first performances were on a little stage jerry-rigged in the Te Kanawas’ house, complete with a curtain; “the curtains would come back,” she recalled, “and I’d get up and sing.” Without a television in the home, music and singing quickly became the primary entertainment. But although her mom played piano, from early on, Kiri eschewed command performances: “I was rather sort of miffy about it even then. I’d only sing when I felt like it.”

Yet where Te Kanawa had a breezy indifference to her own voice, her mother heard something magical: the raw beauty and talent of her dulcet tones. She told her daughter one morning that she had seen a wondrous vision of Kiri singing at London’s Royal Opera House in Covent Garden. Soon, for Te Kanawa’s mother, transforming that vision into reality became her own life’s dream. But the journey from the languid, peaceful New Zealand coast to top billing in London and New York, and then super-stardom literally around the globe, was a long and arduous one. Te Kanawa says simply that it would take “years and years” to detail how much her parents sacrificed for her, adding with genuine emotion, “the reasons that I’m here today is because of the sacrifice of my parents.”

Te Kanawa began her remarkable rise in the most ordinary of venues, singing at a local school. From there, she would go on to perform at weddings and funerals. The money she pocketed helped pay for her basic necessities, like clothes, as well as for her singing lessons. By 1956, wanting to do whatever they could for their daughter’s talent, the Te Kanawas had packed up for Auckland, New Zealand’s largest city, so Kiri could study with a former opera singer turned nun, Sister Mary Leo, at St. Mary’s College for Girls. The schedule was brutal and the schooling, more often than not, a disaster. Te Kanawa was routinely plucked from class in the middle of her lessons to work on her singing whenever Sister Mary was free, and as a consequence, her grades suffered. Within two years, Te Kanawa was asked to leave St. Mary’s.

Undaunted, she enrolled in a business school, where she learned to type and write in shorthand. But she never gave up on her singing. She took a job as a receptionist and then as a telephone operator so she could work at night and study singing during the day. And with pluck and daring, she began to enter competitions. Her breakthrough started in 1960, when she won the Auckland Competition. From there, it was on to voice competitions in Australia. By 1965, she had won most of the South Pacific’s major vocal prizes. She also sang in music show choruses and nightclubs — during one memorable performance, Te Kanawa, dressed all in white, serenaded a drunken club crowd with “Ave Maria.” Then, at age 21, having banked her prize money and earnings, not to mention a scholarship from the New Zealand government, she set off across the globe to England. There, she would finally sing in her first opera.

Te Kanawa enrolled at the London Opera Centre and began her formal instruction in earnest. After a master class at the Centre, it was the celebrated Australian conductor, Richard Bonynge, who told Te Kanawa that she was a soprano, not a mezzo soprano. In 1967, she married Desmond Park, an Australian engineer whom she met in London, and within seven years, her life would be utterly transformed. Her first milestone was finding former Vienna opera star Vera Rozsa, who became her singing coach. Rozsa systematically schooled her in interpretation and stage acting, as well as the technical aspects of operatic singing. By 1970, fulfilling her mother’s dream, Te Kanawa made her debut at the famed Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, singing the roles of Xenia in Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov. She also appeared that season as a flower maiden in Wagner’s Parsifal, but the performance that began her stratospheric rise was as Countess Almaviva in Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro in December of 1971. For that, she earned 50 to 100 English pounds per week, a salary that remained unchanged for the rest of her five-year contract.

Critics have described Te Kanawa’s voice as having a “platinum tone and regal aura,” but she herself is far more regular than regal; she has often said that she prefers rehearsals with her fellow cast members to full operatic performances. Indeed, Te Kanawa describes opera, which requires not simply singing talent, but the ability to act and move in concert with all the other performers on the stage as, quite simply, “a mess.” She explains, “There’s the music. There’s the coaching. There’s the instruction. There’s the language. There’s the stage movements, the conductor, the agents, singing teachers, and everybody else.” It is, in her view, nothing short of “a circus.” Actually, Te Kanawa marvels, “You feel as though your brain is going to break.” Her answer, she says, is to retreat into her “typical South Pacific, Polynesian mode” of just going “whoo” and not taking any notice of the whirlwind around her.

In 1974, Te Kanawa was released by Covent Garden to journey to New York’s Metropolitan Opera as the understudy for noted soprano Teresa Stratas, who was headlining as Desdemona in Verdi’s Otello. Te Kanawa watched a dress rehearsal, ran through the entire staging on a cold and snowy Friday and then went home to bed. The next morning, she awoke and contemplated a day of shopping. Stratas, after all, was the one who was the marquee star, and the one who was set to take the stage. Then the telephone rang. Jokingly, she told a friend who was staying with her that if it was the Met to tell them that she had indeed “gone shopping.” The friend took her at her word and hung up. The next call, from Te Kanawa’s agent, was far more frantic, telling her to get down to the opera house. Without even so much as a dressing gown in hand, she hailed a cab on the snow-covered New York streets and hopped in. The cabbie, it turned out, was from Brooklyn and had never been to the Met. Te Kanawa ended up directing him herself and raced through the front door. The matinee curtain was rising imminently, and the backstage staff bundled Te Kanawa into her wig and costume and makeup. The performance was scheduled to be broadcast across the United States. There was, she remembered, no time for nerves, only “all-out panic.” This one illustrious performance made Kiri Te Kanawa an international sensation. Remarkably, she made her New York debut with not a single friend or family member in the audience. “I went on, the loneliest person in the world.”

Te Kanawa still has mixed emotions about that unprecedented debut, describing it as akin to being “in a jumbo jet going faster than anybody else in the entire planet on that day.” And even the charmed career that followed — demanding performances around the globe, media profiles, numerous recordings, the legendary status as one of the world’s greatest opera stars, and in 1981, the personal invitation to sing at the wedding of England’s Price Charles and Lady Diana Spencer at Westminster Abbey before a record global audience of over 600 million — has left her with an imprint of surprisingly ambivalent feelings. An early riser, Te Kanawa never enjoyed late-night post-performance parties or suppers, preferring instead to return home and go to bed. Almost indifferent to the public eye, she dismisses many of her accolades, saying that praise simply “comes and goes.”

There also remains in Te Kanawa a wistful sadness about the high price of a career that required her to live out of suitcases for months on end. In fact, for all the thunder and noise of the opera stage, she hears with equal and even keener precision the silence, describing the loneliness of leaving the stage after being cheered and handed flowers: “Then you go back to the hotel and all the flowers are dying. And it’s very lonely in the hotel room. There’s nothing there.”

Her own life too has had its quiet hurts and tragedies. Te Kanawa’s mother died not long after her 1971 debut at Covent Garden. After a serious bout of illness that forced her to quit performing for three months, Te Kanawa and her husband adopted a daughter, Antonia. Three years later, they adopted a son, Thomas. But the marriage ultimately could not hold; she and her husband divorced in the late 1990s. She zealously guards her private life, but cryptically says, “if you’re going to have a career like this, I think there’s huge problems.” In part, she blames her career for the break-up of her marriage and suggests that it took a toll on her children. Moreover, at more reflective moments, she wonders if she should have given it all up and left the stage. “Sometimes in the darkest time, when I regret a lot, in that dark part of the night when it’s really black, I just see this stinking career took so much. Yet it gave me so much.”

Glamorous, elegant, stunningly beautiful, Kiri Te Kanawa is still a household name. The little girl from a tiny corner of New Zealand ultimately rose to become a Dame Commander of the British Empire and the recipient of distinguished honorary degrees from Oxford and Cambridge Universities. A concert she gave in Auckland attracted a record-breaking 140,000 fans, and she sang the first song of the new millennium in Gisborne, to a global audience in over 80 countries of some one billion. She was also invited to perform at Buckingham Palace for Queen Elizabeth II’s Jubilee.

As an artist, she is most at home among the works of Mozart, Verdi, and Strauss; Mozart, she has often been told, is the perfect match for her voice. She once described Strauss as “music that fits me like a glove, lyrical and passionate at the same time.” Yet for her own pleasure, Te Kanawa prefers the sounds of the instruments alone; in periods of solitude, she listens to Wagner’s orchestral music, rather than having “to pay attention to voices.”

Te Kanawa remains a deeply patriotic New Zealander, who seeks solace and rejuvenation in the lush, green north coastal region, where the ocean amiably wanders in and out of peaceful inlets. Ironically, the diva who made her mark singing the roles of royalty in elaborate costumes on ornate stages, is a self-described tomboy, who enthusiastically fishes, hikes, boats, plays golf and tennis, and even shoots clay pigeons. Now retired from the operatic stage, she has gradually reduced her engagements, but continues to perform in concert. Her current passion is the Kiri Te Kanawa Foundation, which she founded to help support promising young New Zealanders with musical talent. The Foundation provides them with mentoring, coaching, and some financial support. She hopes to open doors for them, something she lacked early in her own career. She shares her simple formula for her own success, that she “never ever missed a green light.” She adds that, walking down the street, she would not stop for a red light. “I’m sort of criss-crossing to get to the green light all the time. And that’s been my aim in life: to never miss an opportunity.”

Dame Kiri Te Kanawa performed at the 2006 International Achievement Summit in Los Angeles, accompanied by Academy member John Williams and the L.A. Philharmonic. Watch Dame Kiri sing “O mio babbino caro” from Gianni Schicchi by Giacomo Puccini.

Before she became an internationally celebrated opera star, Kiri Te Kanawa struggled to earn money to pay for her singing lessons. She worked as a telephone operator and performed at weddings and in night clubs to save the money she needed to travel from New Zealand to London. From those hardscrabble beginnings, she rose to dazzle critics and audiences alike with her performances of the classic operatic works by legendary composers such as Mozart, Strauss, and Verdi.

She made her debut at Covent Garden in 1970, but it was a last-minute substitution in 1974 — as an understudy for the role of Desdemona in Verdi’s Otello at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House — that propelled her into opera’s exclusive legion of greats when she was barely 30 years of age.

Her lush and lyrical soprano so entranced England’s royal family that she was personally invited to perform at the wedding ceremony of Prince Charles and Lady Diana — before a live television audience of some 600 million — and later for Queen Elizabeth’s Golden Jubilee. She was also honored as a Dame Commander of the British Empire by the Queen. Having made her mark in performances across the globe, Te Kanawa, a deeply patriotic New Zealander with a strong Maori heritage, is now helping to mentor other talented young New Zealand singers and musicians through her Kiri Te Kanawa Foundation.

Tell us about your debut as the Countess in Marriage of Figaro at Covent Garden, in December 1971. Did you have a feeling this was going to be a very big night for you?

Kiri Te Kanawa: No, no. Not at all. I knew that things were working up to it. But you know, when you’re in it, you’re in sort of a mess, because there’s the music, there’s the coaching, there’s the instruction, there’s the language, there’s the stage movements, the conductor. And then you’ve got everybody else coming. You’ve got agents, you’ve got singing teachers. You’ve got this whole world, a circus. You feel as though your brain is going to break, and I think I’m just going to go crazy. I just went into my typical South Pacific, Polynesian mode. I just wouldn’t take any notice of it. I just sort of let it all fly over me. That’s the only way I could cope with it. There’s only so much you can take in in a day. I was coming in from the country. My journey was an hour and a half. I was working long hours, so I could only take in so much.

You were pretty well prepared. You’d done the role before, albeit in English.

Kiri Te Kanawa: Yes.

I’d actually done the Countess, which was very important. I’ve actually done it on stage, yes, with a director. Yes, I worked for several weeks in Santa Fe, which was a wonderful experience. I mean, it was very precious, that experience. I look back and always remember that glorious time. That gave me the strength to do the Covent Garden one. Because I’d done it. I’d been there. And yet, I was in a more superior production, of course. Everything was just super-super-duper. It was really fantastic.

That night in December of 1971, when you first sang the Countess at Covent Garden, did you realize immediately what a big deal this was for your career?

Kiri Te Kanawa: No. I don’t think I thought about that until it really took off. Suddenly, you’ve got agents and jobs, and you’re doing this and doing that. You’re wanted everywhere. And there’s interviews and newspapers. And the Met’s calling and Covent Garden is booking you again. And then Glyndebourne suddenly wants you. Once again, this melee, and I just went into my little spot of just going into cuckooland and not taking too much notice of it for awhile. And then you can cope with it. There was a time when I couldn’t cope a couple of years later. I just overdid everything and decided to take a huge break because it was all too much.

When you’re in that kind of demand and you’re fairly new in your career, it must be hard to say no to very prestigious invitations.

Kiri Te Kanawa: I think it’s harder today. It’s harder today to say no, because there’s less around. And there are a lot more singers who will agree to do anything and sometimes not be capable of doing it. That’s what I’m more worried about, the singers who do a job, an opera, performance of whatever type, and then after the performance, they’ve basically killed their voice off. That’s what I’m more worried about today.

When you approach a role like the Countess in Marriage of Figaro, do you approach it all together, the singing, the acting, the words? Or do you just learn the music first?

Kiri Te Kanawa: Gosh. Now that you ask me the question, it’s going to be hard to answer.

First of all, of course, you’ve got to know the music. You’ve got to know all the different things. And so the music came, of course, first with me. Then you had to know what you were doing, then you have to know what your colleagues were doing. You had to know what they were talking about and how they were moving around you. And then you have to make sure that your timing — and your colleague was not, as they say, upstaged during what you were doing. So you had to sort of take your place in the jigsaw puzzle. And the jigsaw puzzle was doing your job within the job. But yet, always being part of the action and having the energy behind all you were doing. So you all live with the same mission, was to complete the story and tell it to the audience. That was my thing all the time. Make sure the audience knows what we’re doing. Of course, you know, surtitles and subtitles have come out. And I think that’s wonderful. Because the audience, if they don’t speak the language, they’re right in it with you. You say, “I understood every word!” And I think, “Yes. Of course, you did.” That’s fantastic.

Can you talk about performing “Porgi, amor” in Marriage of Figaro, and the effect it had on the audience? How did you prepare yourself for that, and how did you react when the audience went crazy?

Kiri Te Kanawa: Well, I never ever believed in any accolades. Because I sort of thought if my singing teacher says it’s okay, and the people who are really, really close to me — and there are only one or two — if they say it’s okay, then I wait for that signal. I wasn’t really taken in by it, and still haven’t been taken in by it because accolades come and go. It’s how you feel about yourself.

I do remember the preparations every night, and during the dress rehearsal, that the pianist would come to my room and we’d go up, walk up two or three flights above the dressing room. And I’d literally sing that aria four times through. And then I’d be in costume. And I’d walk. I’d have my costume on. I was all ready. And from that point of work, singing it through three or four times, very softly — never sing full voice — I walked straight down to the stage, sit in position and I was ready. And that’s how I did it. And I continued to do that for many years, every time I did Figaro.

So you went through the whole aria four times before singing it onstage?

Kiri Te Kanawa: It was just another time through by the time I got on stage. It wasn’t more important than the first one or the sixth one I was going to do. I was singing it and singing it and singing it and singing it. It’s one of the most difficult arias in the repertoire. It sits horribly for the singer because it’s a long wait. You’ve got to wait out the first act, and you’re listening to what’s going on, and of course you’re getting more nervous. But there wasn’t time to get nervous because I was too busy singing the aria through. So I had no time to think about anything. That’s what the whole thing is when you’re occupied, you just go on and do it.

You had a remarkable debut at the Metropolitan Opera, when you went on as a last minute substitute for Teresa Stratas in Otello. What was that like?

Kiri Te Kanawa: Gosh. I was brought over to cover Teresa Stratas and watch the production. Covent Garden had released me but I think they resisted my coming here. They weren’t too pleased that I was coming to the Met. They said it was too soon, and I think there was a little bit of opposition there. But anyway, that was fine. I came. And I was going there, watching rehearsals, watching everything they did. I went through the dress rehearsal, watched it, and thought, “Gosh. This is fairly amazing,” and then went home and that was it. That was the end of it. Jon Vickers came into one or two of the rehearsals, and they said, “Let’s go through the whole thing with Jon,” which I did. And it was a horrible afternoon. I went home and it was starting to snow. And I thought, “Well, that’s that.” I woke up the next morning and I thought, “Well, I’ll just go shopping or something.” And then I was going to go to the afternoon performance. And I had someone staying with me.

The telephone rang, and I said, “If it’s the Met, tell ’em I’ve gone shopping,” or whatever it was, and she did. And it was the Met, and she hung up on them. I thought, “God damn it.” I said, “What did they want?” “Oh, they want you to call.” I said, “What? They called?” And I thought it seems like, you know, my antennae went up, and I thought something’s gone wrong. Anyway, I think my agent called me and said, “I think you’re going to have to get down there.” Well anyway, I sort of threw some clothes on. I didn’t have a dressing gown or anything. So he went to the store, got something for me to wear in the dressing room. All hell went loose. I got in a taxi — who came from Brooklyn, didn’t know where the Met was. I said, “But it’s straight down this street here.” I didn’t know where the street was. I was up on 79 or something. And I thought, “This is getting worser and worser.” It was snowing, it had snowed all night and there was snow all on the road. And the guy was saying — I said, “Look. Just stop here. That’s the Met. If you ever need to know it again, there it is.”

And so I rushed across the square or the plaza, straight through. I think you were able to go through the front door by that time. And I did.

I just went like a mad thing through the front door. And everyone was there. Of course, it’s once again the circus. That “bzzzz” that’s going on. And there’s every man and his dog is there trying to give you information. And there’s the director trying to do something and the conductor’s there. Of course, Jimmy’s there. And Jon Vickers is there. And they’re all there. And you think, “Shut up and get out!” And I just said, “I just need time.” So somehow people threw a wig on me and some makeup and we were on. We’re on the number 52 bus to heaven. So it was like that. It was just this absolute panic. And then I got through the first act. And I thought, “Thank God!” And you know, no one — none of my family — my singing teacher was going to be there in a few weeks to come and see my first performance. And my husband, who was then, was going to come. And all my friends were going to come. And I couldn’t get them, because it was snowing. And it was just — it was impossible. So I went on, the loneliest person in the world.

And I did this performance. And it just went crazy. And I thought, “I think this is what it’s like to hit the jackpot.” It was just the most crazy day in my life. And then for two days after that, it just went sort of crazy. And I thought, “I’m going to have to come down to earth soon. I’m just going to have to start being realistic.”

Were you nervous?

Kiri Te Kanawa: There was no time for nerves. I was absolutely in a panic. Nerves, I was past that. It was beyond that. I was in a panic.

But you knew the role of Desdemona, and you’d had at least some rehearsal.

Kiri Te Kanawa: I think so. I was young and stupid. I was not even 30. When you’re young, you’re invincible. You can do anything you like. And I’ve certainly thought back, and I look at young people now, and I think, “God, they’re young!” I was young, and you could do anything you liked, and I thought, “I can handle this. I’m fine at all this.” And I did. I handled it. Then I had to wait another month to go on for my real performance. Of course, I was more nervous then, so it was a crazy time. It was one of the most exciting two or three days of my life.

Desdemona is a very beautiful and demanding role, dramatically as well as musically.

Kiri Te Kanawa: Oh yes, it’s one of the best. And I wouldn’t have changed a single moment in all of it. And then having someone like Jon Vickers sitting next to you, that’s amazing. People have done debuts like that before, but I don’t think anything as extraordinary as that. For someone who least expected to go on at 11:00 in the morning, and I’m on at 2:00. That was so far out of my zone, I was not there. But I made it. I made it. And I did it.

After that, you must have really been in demand.

Kiri Te Kanawa: Yes, then it all started. That’s basically what happens in a career if you’re lucky enough to have that sort of start. You’d like it to go a little slower of course, as I would have done. I would have been happy. Two years before, I had a little Covent Garden debut basically, but nothing as whiz bang. I was sort of in a jumbo jet, going faster than anybody else in the entire planet on that day. I look back, and I think, just a moment of that again would have been nice to sort of experience. Because when you’re in it, it’s just going too fast. But I could relive it sometimes, which was nice.

In 1981, you were invited to sing at the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer. Six hundred million people around the globe were watching on television. What was that like?

Kiri Te Kanawa: I suppose it wasn’t quite as bad as the debut at the Met, but it was close. It was, once again, a huge melee of people, and the right things to do and the wrong things to do, and where you had to be. And there’s no toilet. So be sure you know what you’re doing. And I thought, “Well, I have to drink.” I think if there had to be a down side of it — I did the silliest thing in my entire life, but I wanted to do it. Because I’d done it sort of the way I wanted to.

I decided to do Cosi and Don Giovanni side by side. One night would be Don Giovanni, one night would be Cosi fan tutte. One night off. One night it would be Cosi fan tutte and one night it would be Don Giovanni. Night off. I did that four times, and nearly killed myself, because we all did. There was a little bit of a pact amongst us, Tom Allen, and I can’t remember who the others were. But we all decided to do these roles, two of them, for Covent Garden. It was like a Covent Garden fest. I think there was most probably (Magic) Flute, Don Giovanni, Cosi and Figaro. I’m not sure if I — I’m pretty sure I did the Don Giovanni and the Cosi. I can’t remember exactly. And in the middle of it, I did the royal wedding. And I thought, “How dumb is this, to have got myself to this stage that I’ve just actually wiped myself out? There’s going to be no voice left.” So I went and stayed up in London for two weeks in a hotel. So I’d go and do the performance, I’d walk down back to the hotel. It wasn’t very far from Covent Garden. And I’d get in that bed and I’d sleep all day. And I’d get up, get up for air, go and have a meal and go back to bed. And I’d shut up for the whole two weeks and just stayed in bed and sang, bed, sang. And that was it.

And I got to the royal wedding by chance. I can’t remember the exact day, what my schedule was. But Covent Garden and then the royal wedding! I thought, “Oh God. I’ll never do this again!” Because it was already set in stone. The productions were set in stone. I was booked to do it. Then the royal wedding came up, and I thought, “Oh my God, how am I going to get through this?”

How did you receive the actual invitation?

It came through Covent Garden. It was John Turley, and he must have rang my agent. Then my agent rang me. And he said, “Charlie wants you to sing at his wedding.” And I said, “Charlie who?” He said, “Charles.” I said, “Charles who?” “Charles Windsor.” “Oh,” I said, “that Charles.” Because I already knew a Charlie. He’s my driver. I thought, “What am I doing singing at Charlie’s wedding? He’s already married. ” It wasn’t that Charlie. It was Charles. So that came through like that. And they said, “And you can’t say a single word.” That was it.