That's one of the horrors of war, that you can train a person, train them to hate, train them to kill.

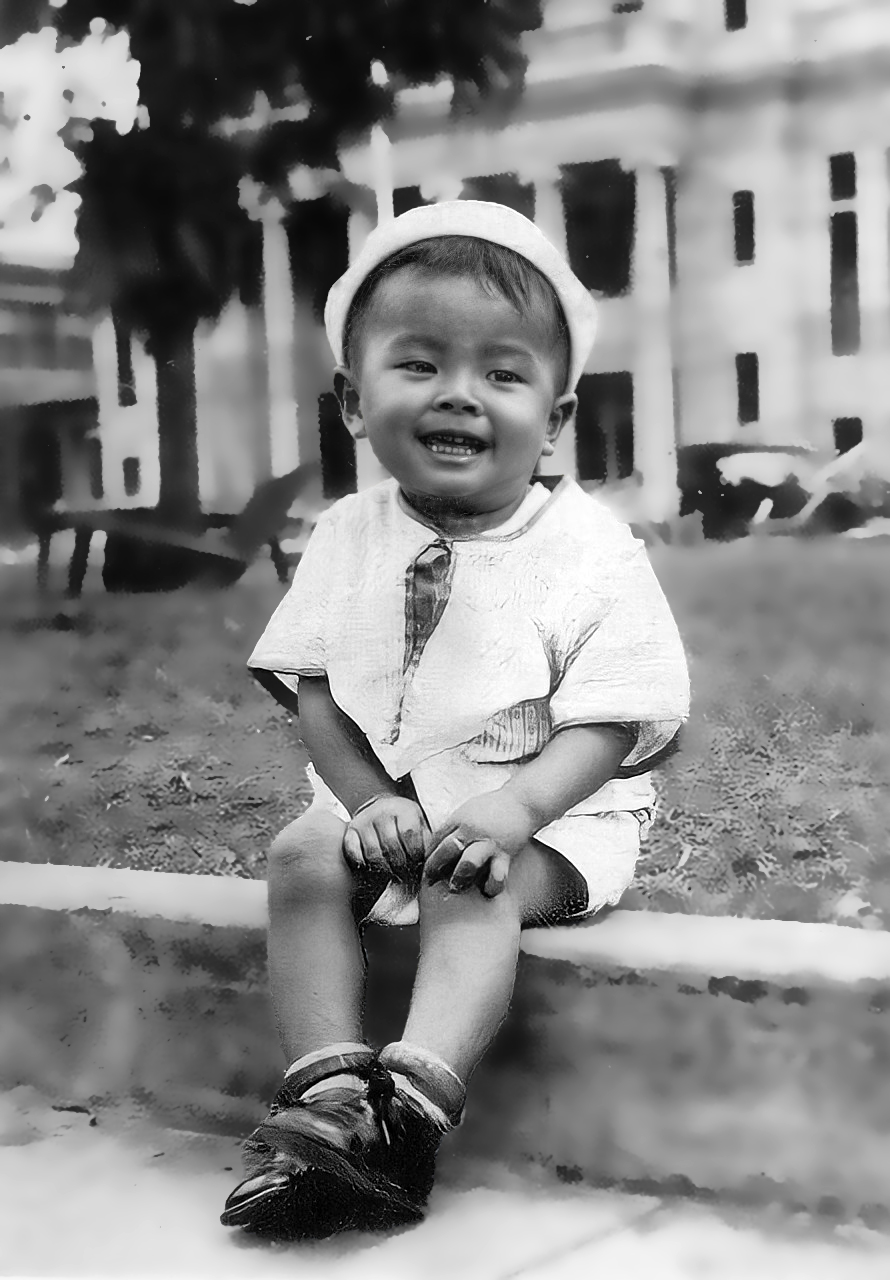

Daniel Ken Inouye was born in Honolulu, Hawaii. His father’s parents, like many others, had come to Hawaii from Japan as laborers, to work on the sugar plantations. His mother, also a child of Japanese immigrants, was orphaned at an early age and later adopted by a Methodist bishop. Daniel Inouye was raised in the Methodist faith and named for his mother’s adoptive father. At the time, Hawaii was a territorial possession of the United States, but not yet a state. Political life on the islands was dominated by the white business community, particularly the sugar companies known as “the Big Five.” Although the Inouye family placed a strong emphasis on education as the route to success, that route led through a school system where opportunities for Asian American students were severely limited.

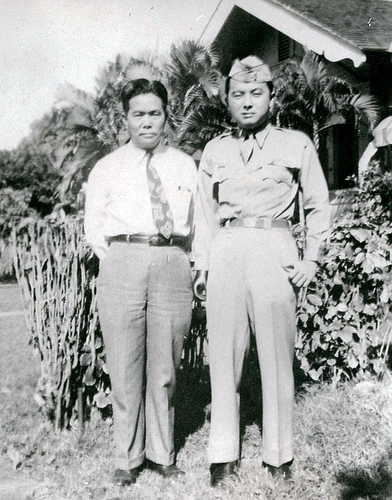

After undergoing orthopedic surgery for a wrestling injury, young Daniel decided he wanted to become a surgeon himself, and planned to study medicine. In high school, he volunteered at the Red Cross Aid Station. He was 17 when Japan attacked the U.S. naval base at nearby Pearl Harbor, and as a medical aide, Inouye was among the first to treat the wounded. Even though Japanese Americans on the mainland were being interned by the U.S. government as potential security risks, Daniel Inouye and his peers were eager to serve their country. At first the War Department classified the Nisei (American-born children of Japanese immigrants) as “enemy aliens,” unfit for service. But after Inouye and others petitioned the White House, the Army accepted Japanese American men for service in segregated units. By this time, Inouye was enrolled in pre-medical studies at the University of Hawaii. As a pre-med student and an Aid Station worker, he was exempt from military service, but he quit his job and dropped out of school to join the all-Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Inouye distinguished himself in basic training, although he struggled to reconcile the violence of war with his Christian beliefs. Within his first year, he was promoted to sergeant, and became a platoon leader. His unit participated in the brutal Rome-Arno campaign of 1944 and Inouye was shocked to learn how quickly he became accustomed to killing enemy soldiers no older than himself. After D-Day, the 442nd moved to France. Inouye distinguished himself further in combat in France; shortly after he turned 20 he was promoted to lieutenant. He was awarded the Bronze Star for his service in France, which included the two-week mission to rescue the “Lost Battalion” of Texans trapped behind enemy lines. He narrowly missed death in France when a bullet struck him in the chest. His life was saved by a pair of silver dollars he carried in his shirt pocket. He continued to carry them as a good luck charm when his unit returned to Italy to clear the remaining strongholds of Axis resistance.

On April 21, 1945, weeks before the fall of Berlin ended the war in Europe, Lt. Inouye realized his lucky silver dollars were missing. That day, Inouye led an assault on a heavily defended ridge known as Colle Musatello, near the town of Terenzo. Inouye’s unit was pinned down by fire from three machine gun placements. An enemy bullet tore straight through Lieutenant Inouye’s midsection, but he continued to lead his troops forward, hurling two hand grenades into the enemy position. Inouye had pulled the pin on a third when an enemy grenade launcher struck his right arm, severing it almost completely. Inouye’s own live grenade was still clutched in the right hand over which he no longer had any control. Warning his troops away, Inouye pried the grenade loose with his left hand and pitched it into the remaining machine gun nest. With his damaged arm spewing blood, he continued to lead his troops forward, firing his machine gun with his left hand until an enemy bullet struck his leg, and he lost consciousness.

When he revived, he refused evacuation until he was sure his men had secured the captured ridge. Nine hours after he was wounded, when he reached a field hospital, the doctors quickly concluded Inouye had no chance of survival, but he insisted they operate. By then he had been given so much morphine, the doctors could not give him general anesthesia without further endangering his life, so he remained conscious through the operation that followed. The surgeons saved his life, but they could not save his arm. Inouye was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism; he remained in the Army until 1947, when he was discharged with the rank of captain.

At the time, it was clear that Inouye’s exploits, and those of other members of the 442nd, merited the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military decoration, but no Asian American received the award at war’s end. On his return to the States, Inouye and other minority veterans were subjected to much of the same discrimination they had met before the war. Inouye committed himself to the cause of equal rights for all Americans, and for all residents of Hawaii as fully enfranchised American citizens.

The loss of his right arm had ended Inouye’s dream of being a surgeon, so when he returned to the University of Hawaii he pursued studies in government and economics. He married Margaret Shinobu Awamura in 1949, while attending the university on the G.I. Bill. After graduating in 1950, he entered George Washington University Law School in Washington, D.C., receiving his law degree in 1952.

Returning to Hawaii, he took up the practice of law and then served as Deputy Public Prosecutor for the City of Honolulu. Inouye was already active in the Democratic Party and the movement to end the domination of state politics by the “Big Five” sugar companies. In 1954, Inouye was elected to the territorial legislature, where he served as leader of a new Democratic majority. In 1958 he was elected to the territory’s Senate.

Despite fierce resistance from members of Congress who feared Hawaii’s non-white majority and newly empowered unions, Hawaii was finally approved for admission to the union as the 50th state. With statehood imminent, Inouye was elected to serve as Hawaii’s first U.S. Representative; he took his seat in Congress on August 21, 1959, the day Hawaii became a state. He was re-elected to a full term in the House the following year.

In 1962, Daniel Inouye was elected to a vacant seat in the U.S. Senate, where he was soon appointed to the Senate Armed Services Committee. In the years that followed, as a member of the Appropriations Committee and the Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, he won a reputation as a tireless advocate for the development of his native state. Outside of Hawaii, many Americans saw Daniel Inouye for the first time as the keynote speaker of the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. He achieved even greater visibility as a member of the Senate Select Committee investigating charges arising out of the Watergate affair, proceedings which led directly to the resignation of President Richard Nixon in 1974. The daily hearings were nationally televised, and viewers across the country were impressed with Inouye’s tough but fair questioning of the committee’s witnesses.

The Watergate hearings and subsequent investigations had revealed serious abuses in the nation’s intelligence agencies, and in 1975 Senator Inouye was selected to serve as Chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee. Again, Inouye won praise for evenhandedness, as he sought to improve legislative oversight for the agencies without impairing the intelligence-gathering necessary for national security.

In 1984, Senator Inouye served as senior counsel to the Kissinger Commission, a bi-partisan panel reviewing U.S. policy in Central America. The controversies surrounding this issue soon brought Inouye into the national spotlight once again. In 1987, he was called on to chair a special Senate committee investigating the Iran-Contra affair. The administration of President Ronald Reagan had sold arms to Iran, an ostensibly hostile government, with the apparent goal of obtaining Iranian influence to free Americans held hostage by the radical group Hezbollah in Lebanon. Funds from the sales were apparently used to arm the Contra rebels in Nicaragua, violating an explicit congressional ban on intervention in the Nicaraguan conflict. Inouye’s findings were severe, and he accused the administration of creating a secret military establishment answerable only to itself.

In the same year as the Iran-Contra hearings, Inouye assumed the chairmanship of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, seeking justice for the descendants of America’s first inhabitants. Inouye was also instrumental in securing full benefits for Filipino veterans who had served in the U.S. Army in World War II, but who had long been denied the pensions and medical benefits to which they were justly entitled.

An injustice of another kind was addressed by President Bill Clinton in 2000. Although the actions of the Nisei soldiers of the 442nd Battalion were widely regarded as some of the most courageous of the war, none had been recognized with the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military decoration. After extensive review, the Distinguished Service Crosses awarded to Senator Inouye and 21 other Asian-American heroes of World War II were upgraded to full Medal of Honor status. For some, the honor came too late. Fifteen medals were awarded posthumously, but Senator Inouye and the other survivors were on hand to receive their Medals of Honor from President Clinton at the White House.

Senator Inouye affirmed his longstanding commitment to bipartisanship in 2005 when he joined a group of senators from both parties in a mutual agreement to limit debate over judicial appointments. Inouye and his Democratic colleagues in the so-called Gang of 14 allowed long-stalled judicial appointments of President George W. Bush to come to a vote, while both sides forswore the use of the filibuster over judgeships except in extraordinary circumstances.

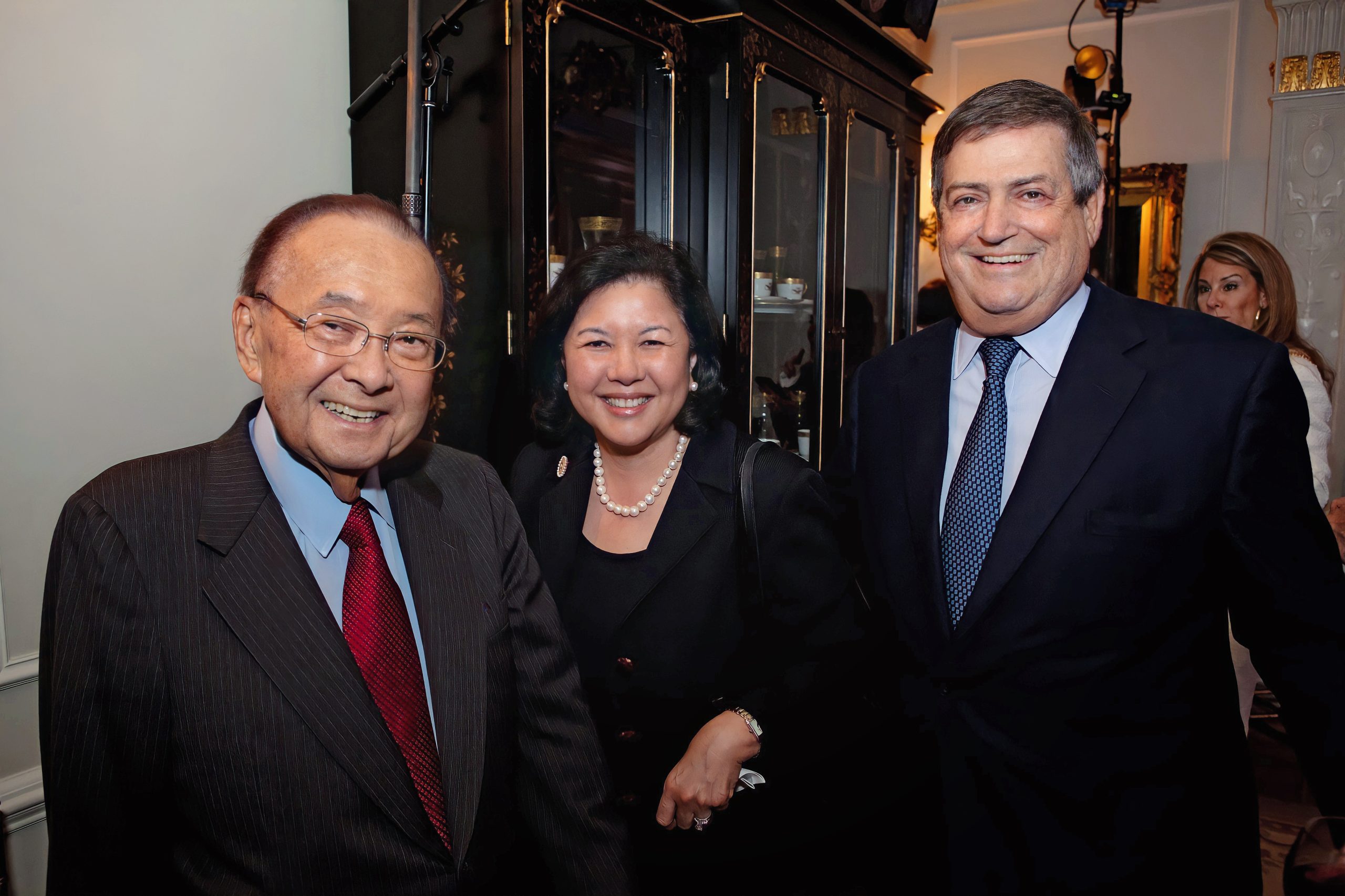

Maggie Inouye, the Senator’s wife of 57 years, died in 2006. The couple had one son, musician Kenny Inouye. In 2008, Senator Inouye, age 84, married Irene Hirano, the CEO of the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. An accomplished administrator, she now serves as President of the U.S.-Japan Council, and chairs the Board of Trustees of the Ford Foundation.

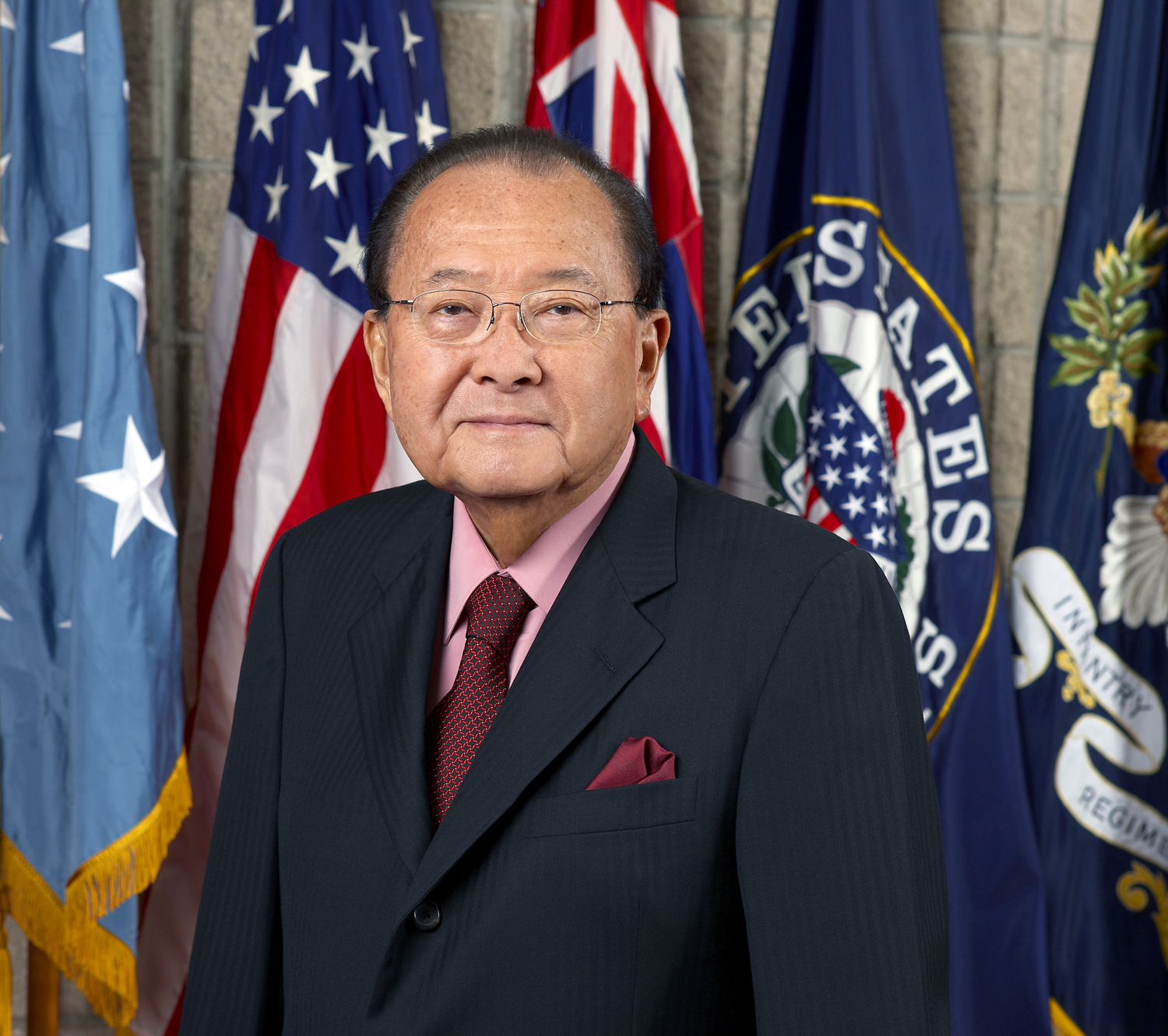

In 2009, Senator Inouye was appointed to chair the Senate Committee on Appropriations, widely considered the most powerful of Senate committee assignments. The following year, he was elected to his ninth term in the United States Senate. After Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia, he was the second-longest serving senator in the history of the body. With the death of Senator Byrd in 2010, Inouye became the Senate’s senior member, and in keeping with Senate tradition was named President pro tempore of the Senate. This placed Senator Inouye third in line of succession to the presidency, following the Vice President and the Speaker of the House. The grandson of immigrant plantation workers, the young man who had been barred from service as an “enemy alien,” had won his nation’s highest honors and risen to the heights of political power.

At age 88, the Senator was admitted to Walter Reed Army Medical Center for treatment of respiratory complications. His wife and son were by his side at the moment of his death. His office reported that his last word was “Aloha.” After his death, Daniel Inouye, who had already received the nation’s premier military decoration, was awarded its highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Daniel Inouye was a 17-year-old high school student in Honolulu when his country, the United States, was attacked by Japan, the country of his ancestors. Initially denied the right to serve, as a so-called “enemy alien,” he fought successfully for the right to wear his country’s uniform and distinguished himself as an infantry officer in France and Italy. In the last days of the war in Europe, he lost his right arm in combat.

After the war, Daniel Inouye became a leader in the movement for Hawaiian statehood, and was chosen to serve as his state’s first member of the U.S. House of Representatives. For nearly 50 years, he served in the United States Senate, an outspoken champion of equal rights for all Americans. Forty-five years after the end of World War II, he was awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroism on the field of battle.

Daniel Inouye was the second longest serving senator in U.S. History. As President Pro Tempore of the Senate from 2010 until his death, he was third in line of succession to the presidency, the highest position in government ever attained by an Asian American.

Thank you, Senator, for sitting down with the Academy today. We’d like to discuss your experiences in the war. There is a story about a face-to-face encounter you had with an enemy soldier that had a big impact on you. Could you tell us about that?

Daniel Inouye: Well up until then I’d killed many Germans, I won’t tell you. This is one secret, because you must keep in mind that if you run across a dog driving, would you ever forget that? You could never forget that, that bump. It’ll haunt you for the rest of your life. Imagine if you killed a human being. You’re not going to forget that. Well I killed many, but this was at a time when I was still a sergeant, not an officer yet. And the machine gun on the second floor had been firing at us and killed one of the men and I was angry. We charged up there, there were three Germans, two were dead and one was alive, but he was sitting on the floor, back against the wall, his legs were wounded. His hands were up, “Kamerad! Kamerad!” And I didn’t speak German worth anything, so I proceeded towards him. Then suddenly he stuck his hand in his jacket, like this. My initial and natural reaction was, this fool is going for his gun. So I swung my rifle up, hit his face on the butt, and he was dead. His hand flew out and up came a packet of photographs of his wife and kids. That’s what he wanted to show me, that he was a father, he was married, he’s got children, so be good to me. I killed him. You don’t forget that.

That’s a situation that a lot of people probably can’t understand.

Daniel Inouye: I told the chaplain, I said, “I don’t think I can continue doing this.” He says, “Well the war is still on, and if we don’t put them away, they’re going to put us away.” So reluctantly, I went along. I didn’t enjoy my work. Up until then I must admit I enjoyed it, and men who have served, some of them have experienced this. To this day I cannot fathom this, but I was a young corporal — a sergeant — leading a contact patrol from my battalion to the next battalion. We were walking along the trail and all of a sudden I looked up on a hill, not too far away, and here’s this German. He’s crouched, he’s defecating. Nothing glamorous about it. And I told them, “That’s mine. Get down.” I set my sights carefully, pshh, boom. And the men all came up to me, “Terrific Dan, terrific!” Killed a human being, terrific, and I felt good. You know? I’m a Sunday school teacher and I felt good. When I think about it, that’s one of the horrors of war, that you can change a person, train them to hate, train them to kill. It’s a terrible thought. You would think that no one can change you, your soul, your heart, your compassion. But here I was, I shot this German and I was proud, and the men around me came around, “Terrific, Dan!” How can you forget that? That was number one.

I had heard a story, Senator, about two coins in your pocket?

Daniel Inouye: Oh, that was my good luck coin.

This is a secret I don’t know if I should share with you, but in my younger days, when I was a sergeant, I ran the biggest crap game in the regiment. That’s achievement! But not to make money. I gave them away because I didn’t want to write home and tell my mother I’m a gambler, because you know she would die. So I didn’t save anything. I gave it all away, so my game was very popular. The losers got their money back, and I saved two silver dollars, and I carried them with me in a bag, a little packet, as a good luck charm, because those two dollars had saved my life. Because a bullet struck the coin, went off, instead of entering my body. So I kept them. The day I got my final injury, I looked for my coins, they were gone. It must have slipped out, so I knew something was going to happen. In fact, I told the platoon leader of the next platoon. I said, “Today I get it.” He said, “You’re crazy.” I said, “No. I know I get it. I hope it’s not too bad.”

Could you tell us about the day you were wounded. When was it? How old were you?

Daniel Inouye: April 21st was the last time. I was 20 then.

And you were in Italy. Can you tell us how that day started out?

Daniel Inouye: I was an officer then, first lieutenant, and about a week before this attack, we had an officers’ meeting and the captain says, “I want you to pledge silence. You’re not going to tell anyone what transpires in this room.” Okay. His words were very simple: “The war is over.” I looked at him. “What do you mean, the war is over? They’re still shooting!” “They’re now negotiating. So be careful, keep up the pressure, because you don’t want to prolong the war. You want to end it fast, so put the pressure on, but be careful.” Well, at that point, you don’t want your men to be wounded, so keeping that in mind, moving up. On that day I was wounded a couple of times. The first one I thought somebody punched me in the stomach, but no one was around. A bullet had gone through my abdomen. Believe it or not, it just felt like a punch, but there’s no pain nerves inside. The pain nerve’s on your surface. It is much more painful if somebody stepped on your toe. So I kept on going. The bleeding was very minor. It wasn’t fatal at that point. Then we were confronted by three machine gun nests.

So you were leading your men forward when you came under machine gun fire from three different locations. How many of you were there?

Daniel Inouye: I think about 15, and I was leading them, so I say, “Stay down!”

To show you how lucky I am — but I knew this was the day — the first one… Boom! The second one… Boom! Until a grenade launcher came directly at me. Instead of hitting me here, it hit my arm. Now that’s luck. Don’t you think so? I lost my arm but I was still alive, until I got hit in the leg and then I couldn’t walk. I must have looked terrible, because with blood gushing out, I’ve got this submachine gun, brrr, like the movies!

You were grievously wounded but you weren’t carried out right away. Is that right? Why did you stay?

Daniel Inouye: You have certain responsibilities as a platoon leader. I wanted to make certain before I left that the men were deployed in positions of defense, because you can always count on the enemy counterattacking. Once you’ve pushed them out, they try to get back. We were now at the high point, and I might as well tell you now, but most people think I got hit by Germans, right? No. In the early stages of World War II, the Italian army, navy, air force surrendered. If you think back to the African war, they surrendered. They sunk the navy, the aircraft were all burnt. One division refused to surrender, the Bersaglieri. They were the — I would say the successors to the Praetorian Guards. In the old days the Praetorian Guards protected Caesar, the dictator. These were Bersaglieri troops, crack troops, protected the king. And their attitude was, “We will put down our arms if the king tells us to do so.” Well the king was nowhere around, it was run by Mussolini. So they fought until the end of the war, and these brave fellows, when the war came to an end I think there were less then 500 out of the whole division. And so if you go to my office you’ll see the hat and the plaque. I’m a member of the Bersaglieri, because years later — I’m a senator now, chairman of the defense committee — I was in Rome as part of the negotiating team for the use of Aviano, the airport. And after the negotiations were finished, I looked at the prime minister and I said, “I’m looking for someone who fought with the Bersaglieri.” He says, “Why?” and I told him. “These were brave men. None of them ever surrendered. They fought until they were killed or wounded, and I just want to shake their hands to say that it was an honor fighting them.” He says, “This general is in charge.” A battalion of Bersaglieri was run by a four-star general, that’s how important they were.

You said you were lucky. How big a factor do you think luck is in life?

Daniel Inouye: I was hoping you wouldn’t ask me this.

I’m supposed to be a normal, sane type person, but after you go through war and such, you become superstitious. I am convinced that somebody is looking after me. Now for example, when I was wounded the last time — I was wounded four times, that’s how lucky I am — none of them killed me. The last one was a terrible one. The arm flew off and everything else. It took nine hours to evacuate me. I was wounded just about noontime, but I stuck around until three, when I felt that the platoon was in shape, then I said, “I’m ready to go.” From three to midnight, because everything was on a stretcher. Today, if I had been wounded under the same circumstances, I would have been evacuated by helicopter and I’d be in a hospital within 30 minutes. As a result, in my regiment — the regiment I served in — no double amputee survived, because they bled to death. No brain injury survived, and that’s what the nature of war was like.

So here I am, I get to the hospital at midnight. I’m in a room about — oh, five times this size — it was a tent. And you can see hundreds of stretchers lined up, and some of the men are dead, some are severely wounded. And there were about three or four teams of doctors and nurses going up and down the line and they’re mumbling. But after awhile I’m watching them, and it became very clear that they were deciding. This one? “Immediately in the surgical room, because he needs treatment.” Next one? “You can wait. Not that serious.” The third category? “God bless you.” Well when the doctors came by, and the nurses, they looked me over and they put me in that category. Category three, that they say good-bye. Because the hospital had so much in resources and so many nurses, and so many doctors, and so many beds. They couldn’t accommodate all. And some of them were already dead or unconscious. So when the chaplain came by, and he’s following the doctors, he came by and he looked at me. “Son, God loves you.” I said, “Oh yes, I know God loves me. I love God too, but I’m not ready to see him.” He looked at me, he said, “You’re serious, aren’t you?” I said, “Absolutely. I’m not ready to go yet.” He ran up to the doctors, and I don’t know what he said, he was mumbling away. Doctors came by, looked me over, shipped me out right away to the operating room. I had to do my first surgical procedure without anesthesia because they were afraid that I might not wake up. See how lucky I am?