A trial is essentially a morality play. You've got to have a narrative.

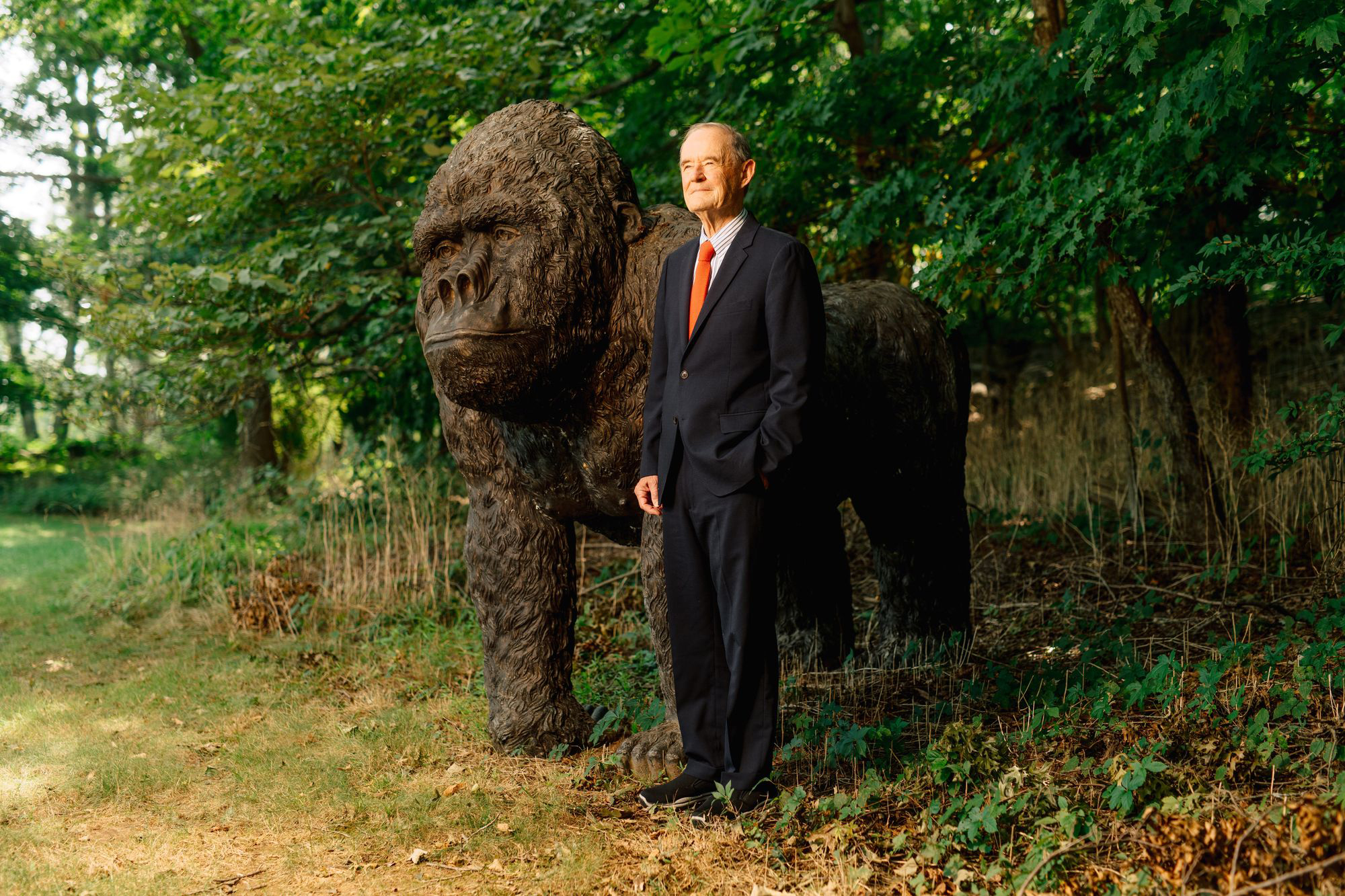

David Boies was born in Sycamore, Illinois, and spent the first ten years of his life in the countryside. Both parents were school teachers, and he recalls being inspired by his father’s passion for American history.

In his first years of school, he had difficulty learning to read, a condition he now recognizes as dyslexia, although the term was unknown at the time. He excelled at other aspects of his studies, and cultivated his capacity for memorization, enabling him to compensate for his disability.

When he was 11 years old, the family moved to Fullerton, California, where he graduated from Fullerton University High School. He enrolled at the University of Redlands, where he completed three academic years in two. He credits reading the Perry Mason novels as a youngster with first inspiring him to become a courtroom attorney. He took the Law School Admissions Test while still in his first semester at college. He won admission to Northwestern University Law School; midway through his program at Northwestern he transferred to Yale Law. At Yale, he concentrated on antitrust law, and graduated second in his class.

He joined the firm of Cravath, Swaine & Moore in New York City, where he defended IBM in a series of antitrust cases brought by the Justice Department and many private competitors. He earned a reputation as a formidable litigator and became a partner of the firm in 1972, two years ahead of schedule. He was 31.

Boies put his expertise in antitrust law at the service of the United States Senate in 1978 as Chief Counsel and Staff Director of the United States Senate Antitrust Subcommittee. The following year, he served as Chief Counsel and Staff Director of the Senate Judiciary Committee. While in Washington, he met Mary McInnis, an attorney working in the White House of President Jimmy Carter. The couple returned to New York, married and started a family.

In 1982, Boies became involved in one of the most heavily reported civil cases of the era, Westmoreland v. CBS. A CBS documentary, The Uncounted Enemy: A Vietnam Deception, had asserted that General William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. forces in the Vietnam War, had deliberately underrepresented the enemy’s troop strength to preserve political support for the war effort. General Westmoreland sued CBS television and its correspondent Mike Wallace for libel. David Boies represented CBS, and his masterful cross-examination of the plaintiff’s witnesses, including the General himself, so impressed the jury that the General agreed to dismiss the case without payment, retraction or apology. Each side issued a conciliatory statement and paid its own legal expenses.

Boies defended CBS again in its successful attempt to resist a takeover attempt by Ted Turner. These and other cases further burnished Boies’s growing reputation as a litigator. While his courtroom exploits attracted increasing coverage from the national press, the attention paid to Boies personally contributed to friction between Boies and some of his colleagues at Cravath, Swaine & Moore. Matters came to a head in 1997, when Boies agreed to represent New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner in a dispute against the other teams of Major League Baseball. Time Warner, a longtime Cravath client, was also the owner of the Atlanta Braves and objected to Boies’s participation in the Yankees’ suit. Boies’s decision to leave Cravath, Swaine & Moore after 30 years made the front page of The New York Times.

Shortly after leaving Cravath, Boies founded a new firm with a Washington-based lawyer, Jonathan Schiller, and the firm grew rapidly. Meanwhile, a case was brewing that returned Boies to his original area of expertise, antitrust law.

In the 1990s, Microsoft enjoyed a virtual monopoly in the personal computer marketplace with its Windows operating system. As consumers increasingly used their personal computers to explore the Internet, upstart companies like Netscape were supplying the needed software. The U.S. Justice Department saw Microsoft attempting to suppress competition in the browser market by bundling its own Explorer browser with Windows, and manipulating the operating system to make it incompatible with competitors’ products. The Justice Department sought Boies’s assistance in the case. At the time of the antitrust suit, Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates was not only one of the most admired leaders in American business, he was believed to be the richest man in the world.

Microsoft’s counsel enjoyed an almost limitless budget to conduct its defense, while the government could only pay Boies and his firm a fraction of the rate he charged his corporate clients. Despite Microsoft’s vast resources, Gates and his colleagues could not stand up to Boies’s cross-examination. The trial judge found that Microsoft had created a monopoly in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act, and ordered that the company be broken up, so that its operating system could be produced by an entity separate from that of its other software products. The appeals court overturned the judge’s ruling but did not dispute the facts of the case and ordered a lower court to reconsider and devise a different remedy. Meanwhile, the Department of Justice and Microsoft reached a settlement, requiring Microsoft to make its application programming interfaces available to third-party developers.

While the Microsoft case worked its way through the courts, Boies took on a case that will be studied and debated for years to come. The outcome of the 2000 presidential election hinged on the results in the State of Florida. The Florida Division of Elections reported that Governor George W. Bush of Texas had won the election by a narrow margin, less than 0.5 percent of the votes cast, triggering an automatic machine recount. When an incomplete machine recount reduced Governor Bush’s margin of victory still further, the Florida Supreme Court ordered a statewide manual recount. The Florida legislature opposed the State Supreme Court’s decision, and the matter was referred to the United States Supreme Court. Partisan sentiment colored every step of the controversy. The legislature, controlled by Republicans, supported the claim of Governor Bush, a Republican. The Florida Supreme Court, dominated by Democratic appointees, ordered the recount requested by the Democratic candidate, Vice President Al Gore.

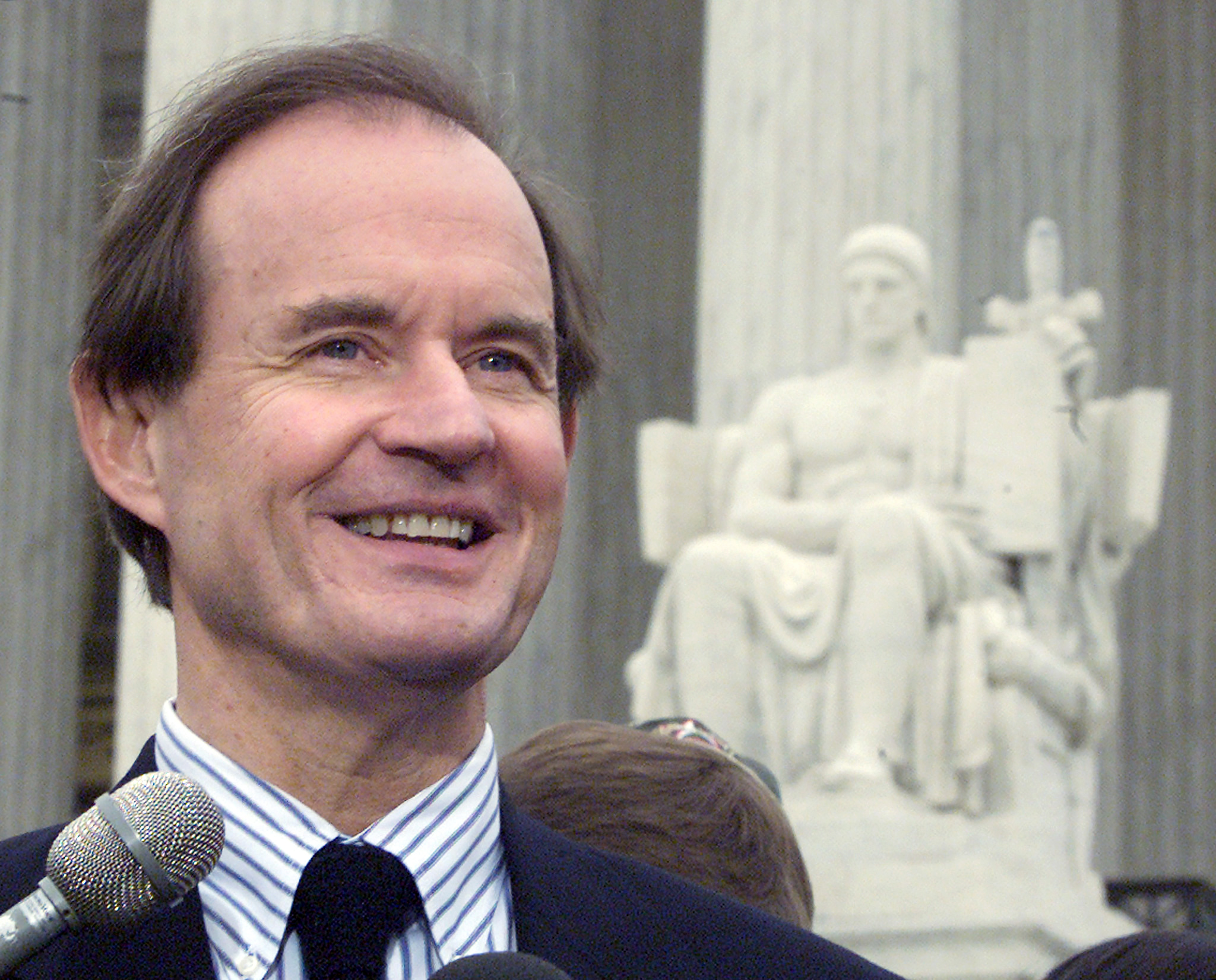

Prior to hearing the case, the Supreme Court voted five to four to stop the recount ordered by the Florida Court. The Court heard oral arguments in Bush v. Gore on December 11, 2000. Governor Bush’s campaign was represented by attorney Theodore Olson. David Boies represented the campaign of Vice President Al Gore. Typically, the Court considers a case for several months after oral argument, but due to the urgency of resolving the presidential election, the Court issued its finding the following day. Voting five to four once again, it ordered a stop to the recount, effectively leaving the state legislature free to award the state’s 25 electors to Governor Bush, giving him the minimum of 271 votes in the Electoral College needed to win the presidency.

Inevitably, observers noted that the five Justices voting to stop the recount were appointed by Republican presidents. Of the four dissenting Justices, two were appointed by a Democratic president, two by Republicans. Although Boies was disappointed by the outcome of the case, a rare defeat in his career, he was impressed by the collegiality of the process, and particularly by the skill of the opposing counsel, Theodore Olson.

In 2009, Boies and Olson joined forces to overturn the State of California’s Proposition 8 ban on gay marriage. The District Court judge ruled in their clients’ favor, finding Proposition 8 to be unconstitutional. In 2013, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Perry v. Hollingsworth that the proponents of Proposition 8 did not have standing to challenge the ruling, allowing the District Court judgment to stand, and same-sex marriages resumed in California. Boies and Olson told the story of the case from their point of view in their 2014 book, Redeeming the Dream. The Supreme Court struck down bans on gay marriage in the remaining states in Obergefell v. Hodges, in 2015.

David Boies continues to chair his law firm Boies, Schiller and Flexner, LLP, with over 200 attorneys in offices across the country. His clients include Altria, American Express, Apple, Barclays, CBS, DuPont, HSBC, NASCAR, The New York Yankees, Oracle, Sony, Theranos, and The Weinstein Company.

David and Mary Boies make their home in Armonk, New York. In addition to his law practice, David Boies enjoys ocean sailing and owns the Hawk and Horse Vineyards in Northern California. Among their many benefactions to education, David and Mary Boies have endowed chairs at the University of Redlands, the University of Pennsylvania, Tulane University Law School, and Yale Law School. They also fund a Mary and David Boies Fellowship for foreign students at the Harvard Kennedy School. Overseas, they support the Central European and Eurasian Law Institute (CEELI), a Prague-based institute that trains judges from newly democratized countries in Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Close to home, they donated $5 million to build a new emergency room at Northern Westchester Hospital, in Mount Kisco, New York, and host an annual picnic for hundreds of incoming Teach for America volunteers. David Boies currently serves on the Board of Trustees of the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, a museum dedicated to the U.S. Constitution.

In August 2024, David Boies, now 83, found himself once again opposing Microsoft, this time on behalf of Delta Air Lines. Following a severe tech outage that disrupted Delta’s operations, Boies threatened legal action against both Microsoft and CrowdStrike, accusing them of gross negligence. This potential lawsuit echoes Boies’s earlier landmark case against Microsoft, reaffirming his enduring influence in high-stakes litigation.

As a boy, raised in a farming community in rural Illinois, David Boies overcame a reading disability and graduated magna cum laude from Yale University Law School. He gained a reputation as one of the top litigators in the profession, praised as a “brilliant lawyer” and “mad genius” for his courtroom arguments in high-profile cases. He represented CBS in a libel action brought by General William Westmoreland, defended IBM in 13 antitrust cases brought by the U.S. Justice Department, and appeared for the Department in its case against Microsoft, winning at trial and on appeal.

A former counsel to the U.S. Senate Antitrust Subcommittee and to the Senate Judiciary Committee, he represented U.S. Vice President Albert Gore before the Supreme Court in the historic case Bush v. Gore (2000). That year, Time magazine named him “Lawyer of the Year.” Theodore Olson, the opposing counsel in Bush v. Gore, joined forces with Boies to challenge California’s Proposition 8 ban on gay marriage. The unlikely team prevailed in Federal District Court, on appeal, and before the U.S. Supreme Court in Hollingsworth v. Perry.

Today, David Boies chairs the law firm Boies, Schiller & Flexner, representing the most dynamic companies in American business, including American Express, Apple and Oracle. He is a leading philanthropist who has endowed chairs at law schools across the country as well as a center for the study of dyslexia at Yale University.

You’ve said that if you couldn’t have been a lawyer you would have enjoyed teaching American history like your father. But some of your cases have put you in the middle of history in the making. Could you tell us about Bush v. Gore? That was the Supreme Court case that ultimately decided the 2000 presidential election.

David Boies: In Bush v. Gore, you had sort of the highest stakes that you can in a politically related case. That was a case in which the presidency of the United States was on the line. And as someone who, as I said earlier, would have been an American history teacher if I hadn’t been a lawyer, just being present at that debate, that litigation, that controversy was exciting. But it was particularly exciting to be part of that legal battle, because it was such a critical battle for the American people, our country, our culture and our law. It was, in some senses, more important than we knew at the time. At the time, I don’t think that most of us fully appreciated the difference to this country and to the world that it made as to whether George W. Bush or Al Gore was going to become president. But what we did know is that it was a momentous decision, and it was a decision where, for the first time in American history, the United States Supreme Court decided a presidential election. There had been one election in the past where three members of the court had participated in a government commission. Three senators, three congressmen and three Supreme Court Justices had assembled together to decide the results of the 1876 election. But never had the Supreme Court, as a court, weighed in to decide a presidential election, and particularly not on a partisan basis.

Tell us briefly about the circumstances. It concerned the vote count in Florida.

David Boies: Al Gore won the popular vote, which in every other democracy is the vote. But of course in the United States, we have what is called the Electoral College, where each state gets a certain number of electoral votes, and those go — with two small exceptions — those go all to one candidate. So if somebody wins California by 50.0001 percent, and somebody loses California by 49.9999 percent, what happens is, all of California’s electoral votes go to the winner. So in a winner-take-all situation, you can get a situation where somebody wins by the popular vote but doesn’t get a majority of the electoral votes. In the 2000 election, it was clear Gore won the popular vote, but the electoral votes — he needed four more electoral votes to be elected. Florida had — and I don’t remember the exact number — but had many times more than what he needed. But if he lost Florida, because he lost all the Florida votes, Bush would be elected president. So the election really came down to Florida. All the other states had been decided. Florida was still undecided. And there were only a few hundred votes that separated the two candidates. And what Florida provided, and had provided for 80 years, is that in those cases you have a manual recount of all the ballots. And the reason for that is that Florida has four different kinds of vote-counting machines. There are four different machines that are used to record votes in different parts of the state. And in order to make it all equal, you’ve got to have a recount that allows people to have a consistent result, which is what the manual recount is designed to do. And we had litigation in Florida as to whether or not we would get that manual recount, and the Florida Supreme Court ultimately held that, “Yes, there has to be a statewide recount. We’re going to recount the entire state to be fair, and we’re going to decide the winner based on the actual voter intent of the particular ballots.” That was what Florida law had always been. The Bush camp appealed that to the United States Supreme Court, and they had two arguments. One argument was a legal argument that said the Florida courts can’t do that, because only the Florida legislature can do that. The Supreme Court rejected that argument six to three. They also, however, argued that the vote count ought to be stopped because it somehow violated the Equal Protection Clause. That decision was five to four against us, and it was a decision that the Supreme Court initially made on a Saturday without ever hearing argument. They heard argument two days later and came out with the same result. But they initially stopped the vote counting before they even had an argument, over the very bitter dissent of four of the Justices. But in our legal system, when the United States Supreme Court makes a decision, that’s the end of the road. There isn’t anything else you can do.

That must have been a tough blow.

David Boies: It was a tough time. It was a frustrating time. It was a disappointing time, and as time has gone on, I think people have moved on from that, and I think that’s the right thing to do. But I think we will always wonder how the world would have been different, how our country would have been different, how the economy would have been different, how our international relations would have been different, the lives that might have been saved, the treasure that might have been saved, if the Supreme Court had ruled five-four in favor of Gore as opposed to five-four in favor of Bush.

Did you realize, taking that on, that this was going to be a very, very important case?

David Boies: Oh, it was clear it was a very, very important case. Important to who became president, but also important to the integrity of our law and the way we resolve disputes. Now, I think that the case, fortunately, is not going to be a precedent for future elections. I think everybody has sort of learned, in retrospect, the lesson that the Supreme Court ought not to play that kind of role. And indeed, even in the Supreme Court decision itself, it says, in effect, this isn’t a precedent for the future. So I think that the long-term damage that the case does to our law is not going to be significant.

The dissents were pretty powerful on that case.

David Boies: They were. Four of the Justices wrote very, very strong dissents, very passionate dissents, and obviously dissents that I agreed with. On the other hand, one of the things that I think is critically important is our belief in and our allegiance to the rule of law. And when the Supreme Court makes a decision, I think we accept it and move on.

Could you tell us the circumstances of Perry v. Hollingsworth? This is the Proposition 8 case concerning same-sex marriage in California.

David Boies: In 2008, California passed so-called Proposition 8 that banned marriage between anybody of the same sex. It just declared that marriage was limited to a man and a woman. And that was contrary to what California law had been immediately preceding that, because the California Supreme Court earlier in 2008 had declared that, under the state constitution, any loving couple had a right to get married. Now when that was changed, that deprived gay and lesbian citizens of the right to get married. And Ted Olson and I brought a lawsuit to challenge Proposition 8 under the federal constitution. And ultimately, the judge ruled that the ban on same-sex marriage violated the federal constitution, violated the Equal Protection and Due Process clauses of the federal constitution, and invalidated Proposition 8. And that decision was ultimately sustained by the Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court on the grounds that the people on the other side, the defendants, really didn’t have standing to oppose the judgment.