Did Lincoln’s position as a moderate within the Republican Party make him more effective during his years in the White House or did it create problems for him?

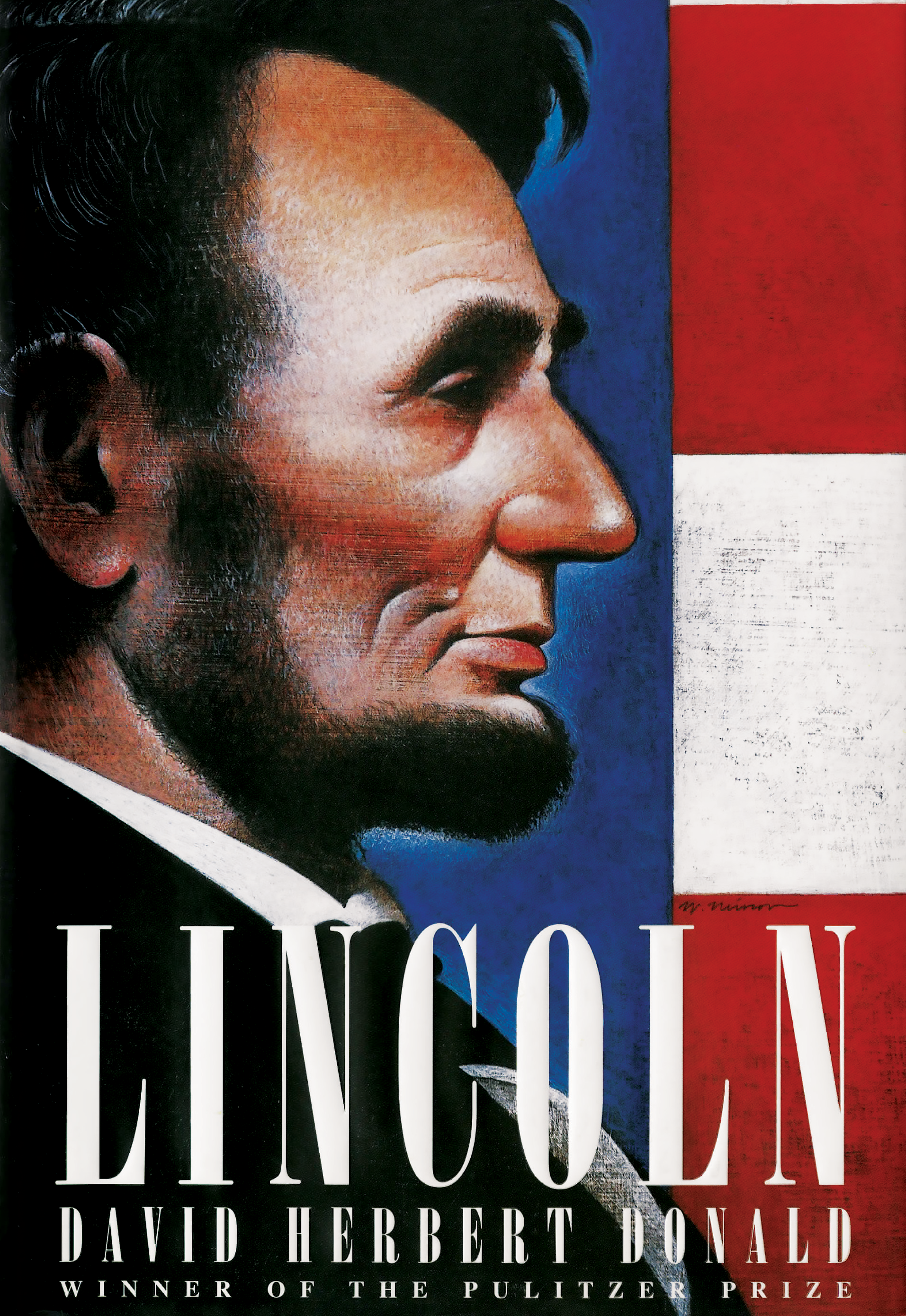

David Herbert Donald: Lincoln thought of himself as a moderate, as somebody who did not go to extremes. There were, within his own party, radicals like Charles Sumner who wanted to act decisively against the South, whether they had the power to do so or not. They wanted to declare all slaves free, they wanted to divide up Southern plantations, and so on. Lincoln was not interested in that kind of dramatic, drastic action. He knew that to get any measure through Congress, he had to have a certain amount of Democratic support. This Democratic support could come from the group called War Democrats, those who went along with Lincoln in fighting a war for the Union, but once he announced, “I am going to abolish slavery. I am going to remake Southern society,” they would drop off, and he knew it. He had a Republican base. He reached out to the Republican radicals, but even more, he reached to moderate Democrats. By the end of his term, he was a centrist, so much so that it was not possible to nominate anybody who would outflank him either to the right or the left. The Democrats felt this, and the Republicans even more so. There was kind of a rump Republican movement to replace Lincoln in 1864, and they thought of people like Salmon P. Chase, the secretary of the treasury, who was indeed a strong abolitionist and a very careful figure in promoting himself. People realized that it wouldn’t work, and he had almost no following, and when he tried to set up a party of his own, Lincoln let him go his own way. He didn’t dismiss him from the Cabinet for ages, and when Chase was ready to form his own party, there he was, marching with his banner, and nobody was behind. It was a wonderful feat of allowing people to have their own way, not cutting them off, but gradually working them into your following and very successfully so.

Lincoln showed extraordinary patience with General McClellan during the first years of the Civil War. This led to enormous frustration in the North. Why was Lincoln so patient, and did it ultimately serve a purpose?

David Herbert Donald: Lincoln put up with more from George McClellan than any other person. He repeatedly urged him to take action, and McClellan couldn’t. The army wasn’t ready. “My horses’ mouths are sore.” And Lincoln wrote, “What on earth have your horses been doing that makes their mouths sore?” He couldn’t get supplies in time. He was not ready to attack. There would be all of these things. Why didn’t Lincoln fire him? One big answer and good answer is that there was nobody to take his place. Ultimately, Lincoln did dismiss McClellan and look what happened. In his place, there was Burnside, bumbling Burnside, who led to catastrophe. Oh, good gracious. There was Joe Hooker, who boasted he was going out and kill all the Southerners, and he again had disaster. They could not lead. There was nobody in the offing that Lincoln could say, “Ah-hah! If I put this man, he would do better than McClellan.”

Now, over two years in the West, he watched very closely as generals developed, away from Washington, away from his overseeing eye, away from politics, and several of them were becoming major figures, notably Grant and Sherman. Watching them closely, Lincoln thought, “Ah-hah! This is the team that I really ought to have.” So when the final blow came — it became necessary to dismiss McClellan — Lincoln turned at once to Grant. He went out to the West. He did not know Grant. Maybe they had met once, but I think probably not. Grant did not know him, but Grant was a very loyal soldier in contrast to McClellan, who played his own hand. Grant would do whatever the president wanted and do it extremely well, as he had already done in the West. He brought him to Washington. He made much of him, and Grant was indeed totally loyal to Lincoln. So this is the evolution. Would McClellan ever have fought a battle if he’d been in power, a major battle? Would he ever have won a victory? I think nearly everybody agrees not. He might have had an occasion and then pulled back before he got underway. He probably would have retreated and tried a new plan or maneuver. McClellan was not an aggressive soldier. His forte was arming, getting equipment, getting the horses ready, all the entourage, but not for fighting. Grant, on the other hand, cared little about this. He appeared in his old work uniform, no epaulets and medals and so on, all ready to go. He settled down at once to work, not for show, and he got the results.

As you see it, what were Lincoln’s beliefs about slavery before the Civil War, and how did his thinking change during the course of the war?

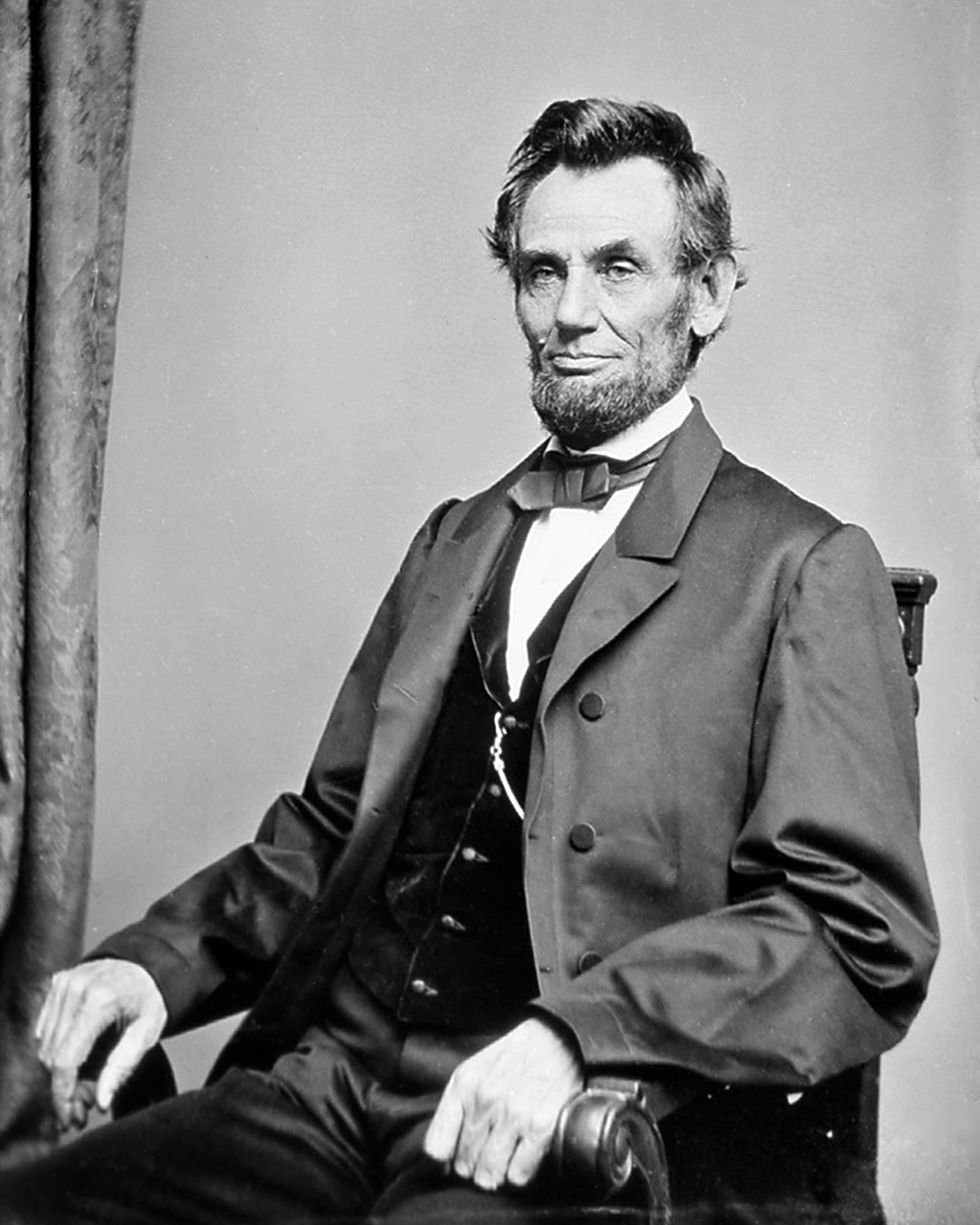

David Herbert Donald: Abraham Lincoln, as a young man, knew almost nothing about slavery. He was born in Kentucky, but he was too young to have any memories there. In Indiana, of course, there were no slaves. In Illinois, he saw very few blacks. They were not enslaved. He did take a visit to Louisville and its environs and was well treated there by a great plantation which did have slaves, but he didn’t really know much about slavery. So what his concern was in those early days was not particularly slavery, though I’m sure he thought of it as a bad institution. What he was thinking about was how it impinged on the white settlers, how it would make areas like Kansas, for instance, a slave state — or rather, that it be free. Kansas would become a new, shall we say, South Carolina rather than a new Pennsylvania. This worried him a great deal. So his early stand about slavery had to do, very simply, with its expansion. He did not want it to go further than it was. Now, at the time, a great many people agreed with him that slavery was a dying institution, that if you could constrain it, if you put these limits around the Southern slave states, they would ultimately have to get rid of the institution itself. It would die of its own accord, and it had to expand in order to live. Now, that was the mindset of the pre-Civil War Lincoln. He was, of course, opposed to slavery, and when he appeared in the Lincoln-Douglas debates, he said flatly, “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.” And he said that “As I would not be a slave, I would not be a master,” but he didn’t plan to do anything particularly about it.

He was constrained by the Constitution, which said this is a domestic institution that individual states rule on and decide about, and if they could just keep it that way, he thought it might be all right. Then the Southern slave states became expansionist, first the move into Texas — that vast area that potentially had the makings of being four more states, all slave states — and then further into the West. Presently, in 1854, Stephen A. Douglas opened up the rest of the national territories to choose whether they wanted to be free or slave. From Lincoln’s point of view, this showed slavery on the warpath, that “We’re going to be hurt here because slavery is going to encircle us rather than we contain slavery.” So his views became stronger, but even so, he did not propose any practical measures to do away with it. Then comes the secession of the Southern states. He becomes president of the United States. What should he do? In his first inaugural, he assured the Southerners that, “Your peculiar institutions are safe in my hands.” That sounded all right, except the Southerners didn’t believe him, and they started withdrawing from the Union, and as they did, he increasingly came to see that they were withdrawing because of slavery. Slavery was the central institution in the Confederacy.

Furthermore, living in Washington as president of the United States, he saw a great many slaves — also a great many freedmen — and for the first time had some acquaintance with blacks as individual people, notably Frederick Douglass. Before that time, Lincoln had thought of blacks as maybe somebody who cut your hair every now and then or takes care of milking your cow. Now Frederick Douglass appears. This is a powerful man, well educated, an immense orator with a huge following who comes and gives specific plans to Lincoln of what ought to be done, and Lincoln is taken by him. This is a man of intellect. “Clearly, some blacks, at any rate, are as smart as some whites.” And his view toward slavery gradually becomes very different from what it had been. Presently, he came also to see that the Confederacy would not exist — could not survive — if slaves were emancipated because their economy depended on slavery, and if they didn’t have those slaves working in the field, the whites in the army would have to go back and support their families. So something had to be done here. Finally, as the Union armies advanced, more and more blacks flocked around them, hundreds, thousands of them, a kind of black trail, so to speak, following the Union armies, and many of these were able to help the Union fight. And President Lincoln, he enlisted them in the Union armies, so that by the end of his first term, Lincoln had come to have a very different view about blacks and about slavery. And when that occurred, he was now ready to move to the next step.

He knew he could not unilaterally free all the slaves successfully. His constitutional powers did not allow it. He could free them under military order, but that might not be constitutional. It might not last. The time had come for an amendment to the Constitution. And Lincoln, as a practical politician, worked carefully with the Congress to get exactly the number of votes that were needed to pass the 13th Amendment and, of course, it was, to his great joy. He also came slowly and sometimes reluctantly to see that blacks were people of real achievement, that they served nobly in the army, and they did very well at places like Fort Hudson, where they led in the attack. They were to be depended on, and when it came to the question of reorganizing the Southern states once they were conquered, he began to see that we are going to have to take blacks into account; we are going to have to see that they are freed. And the best way to do this is to see that at least some of them — at least the educated ones — ought to have the vote, and this was rank heresy, something that Lincoln in 1846 would never have said and Lincoln in 1856 probably would never have said. But comes 1865, he realizes we have got these people, they are our allies, and we have got to do something for them, as they have done for us.

What might the aftermath of the Civil War have been like if Lincoln had not been assassinated? How might this have changed the process of Reconstruction?

David Herbert Donald: Historians like to play “if” games and “what if” and “What would happen if Lincoln had not been assassinated?” or “What if he lived after an assassination attack?” And of course, the answer is we don’t know, and nobody does know. We make some guesses. Probably, the readmission of the Southern states, or some of the Southern states, would have been easier. There would have been less draconian Reconstruction measures, and probably, there would have been some guarantee of the rights of freedmen. The Black Codes enacted in Reconstruction would not have been tolerated. Whether this would ever have led to real equality for blacks, I think, is uncertain, and indeed, I’m not sure blacks still have complete equality. Things would have been different also on a political level. Lincoln had just been re-elected by an overwhelming majority. He had now the mandate that he never had in 1860. He was able now to go to Congress and say, “I want this done, and the people are behind me.” And he can move with that fashion, which he could not do earlier, so that measures for Reconstruction could have been enacted by Lincoln that would be more moderate, more careful, slower probably, and on the whole probably even worked out better, but who knows?

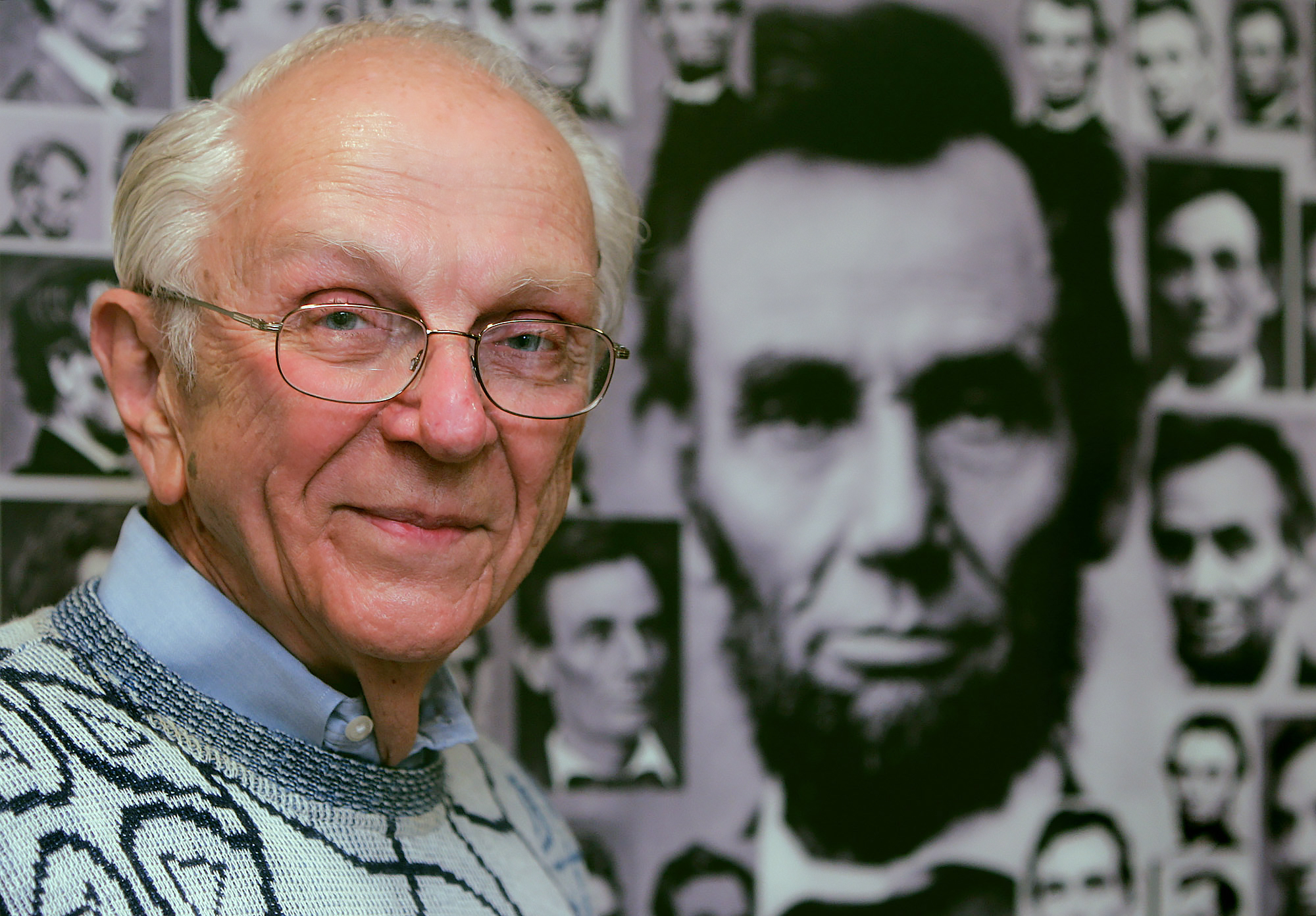

What do you see as Lincoln’s legacy today?

David Herbert Donald: Some years ago, when I didn’t have anything much else to do, I went through a series of newspapers, looking at a presidential race to see how often people invoke Abraham Lincoln. The answer was everybody invoked Abraham Lincoln. If you are a racist, you say Lincoln hated the blacks. If you were an equal rights person, Lincoln loved blacks and tried to give them freedom. If you were a Republican, Lincoln loved the Grand Old Party. If you were a Democrat, Lincoln was at heart really a Democrat; he just ran for the Republican ticket. Everybody loved Abraham Lincoln. Now, some legacy to give is the legacy of understanding this was, first of all, a very great leader, and we’ve had so few in our history. Second, that this was a man of absolute integrity, that you could trust whatever he said, and we’ve had so few people like that in our history. But also, this was a man of peace, who wanted to adjust, who did not want to dominate, who did not want to rule like a czar, who did not want to be an emperor of the South. He had modest goals. He kept to them, and I think that is one of the legacies that our presidents ought to keep from Abraham Lincoln, namely that there are realistic limits on the powers of a president that Abraham Lincoln knew and that we ought to know, too.

We’d like to take a few minutes to talk about the woman behind the man, Mary Todd Lincoln. Can we talk a little bit about Mary and her journey from Springfield to the White House?

David Herbert Donald: Yes. I have great sympathy for Mary Lincoln. Mary Lincoln was left an orphan at a fairly early age. Her stepmother did not like her and pushed her out of the nest as soon as she could. She went to live with her sisters, including the one in Springfield, when she was an adolescent. So she had a hard bringing-up. She had a father who loved her, that’s true, but her stepmother really did not like her, and they didn’t get along at all. So Mary had no experience in close, relaxed friendship with other women, and this made it hard for her when she moved to Springfield. Her sister put up with her, but they were not really close friends. She had very few close friends, and it was easy to take a dislike to Mary because, first of all, she was pretty, she was lively, she was vivacious, and she caused envy among the other young women in Springfield. It’s easy to see why she might well be disliked. All the young men were courting her, and if you were a young woman in Springfield, you might think that Mary Todd is a dangerous character.

Well, she married Abe, and their marriage was in many ways a very rocky one because he really was not used to dealing with women at all. He didn’t know anything about women. His mother had died. His stepmother was an uneducated dear old lady, but he didn’t learn anything from her. He had little association with women of education and competence, so he had to adjust his sights too. It was a rocky first start for them, and they had some serious quarrels, including a break-off of the engagement before they got married. But they did get married, and they decided to make do. It was a hard life for her because he was away so much of the time on the circuit. She was a good mother. They had how many children?

They had Robert. They had Eddie. They had Willie, and they had the young boy called — the youngest — called “Tad” — Thomas. Now, Robert grew up not really knowing his father at all, raised by his mother, and he was not a lovable person. On the other hand, Eddie was always sickly, and we have no personality for him. Willie was apparently the delight of the family. He was smart. He was clever. He was witty. He wrote poems at age eight that were published in the newspapers. He had a wicked sense of humor in the White House as a little boy. As his father was out in front on the stand, he would speak about how we would support our troops and we would support the Union, and the people in front started laughing because there behind him, Willie and Tad, the littlest boy, had got a big flag of the Confederacy stretched out behind him. There was no malice. They were just being funny. When Mary Lincoln was having a big reception, all the ladies in their crinolines and their big skirts, they were all around, and they were in the East Room sipping whatever you gave them in those days. The doors would burst open, and here would be Willie and Tad pulled by a nanny goat on a chair rushing through the flock of ladies, who would gather up their skirts as best they could, because they were riding a sled. It was a chair from the White House. They had very little discipline, but Lincoln did not believe in discipline for children. He said, “Oh well, let them grow up as they like. They will be constrained much in the future. Let them try.” Mary was perhaps a little more strict, but she could not bear to punish her children, and she loved them. She doted on them.

We know this in an odd sort of way from digging in the septic tank behind the Lincoln house. There was no garbage collection in those days, so you threw all your waste in a pit behind your house. Some people — I don’t envy them the task — excavated this to find what did the Lincolns eat, how did they live. Rumor had it for years and years that Mary Lincoln was so stingy, she barely fed her family. Well, you dig out the septic tank, and here are bones from the best cuts of beef and the best cuts of lamb. Clearly, Mary kept a good table. She was a good cook, and she fed her family and cared for them very well. She loved them. Now when she gets to Washington, things are different. First of all, she has an old entourage of servants. Most of them had been there from the previous administration, most of whom she did not trust.

Second, she had a budget that she was to remodel the White House, and Mary had no experience with money. She knew the White House was, as Lincoln himself said, “this damned old barn,” and it needed something done for it, and so she went out on a shopping spree to get things for the White House. She went to Philadelphia in the big department stores and looked at what they had in the way of drapes and furniture and so on. She went on to New York and did the same kind of thing, and she ordered like mad, one might say, because $40,000, which she had at her disposal, was a vast amount of money for Mary Lincoln, who had never seen more than, I guess, $100 at a time. So she ordered all these things for the White House, and they came in. She furnished the White House in what was for those days good taste. We would think it is ornate, overstuffed, very Victorian, but people commented on it that it was indeed very nice. And then the bills began coming in, and Mary had no way to pay for them. She committed much, much more than the Congress had allowed, and the manager went to Lincoln and said, “What are we going to do about it?” And Lincoln, for once, lost his temper. He said, “I’m not going to pay for these things, these trinkets that she’s buying, all these foofoos. Why, this house was better when we moved into it than any house we ever lived in out in Springfield. I won’t pay it.” Then he said, “I’ll put it out of my own pocket,” which, of course, he couldn’t afford to do. Well ultimately, they sneaked it into the budget under a different item, and they did pay for it, but Mary Lincoln’s extravagance became well known.

It persisted after that when she bought jewels, when she bought necklaces, when she bought bracelets. She had an irresistible time of buying, and this is more understandable, I think, when one realizes that before she became Mrs. President, she had lost her first son, Edward, whom she loved. Children did die early in those days. She comes to the White House with three boys. Robert himself was actually at Harvard studying, but the other little boys were there, and she wanted them to be well dressed. She wanted them to be well mannered. She wanted things to be exactly right for them, and this is one reason why she bought so much, she spent so much, she cared so much, and she wanted to impress the public. And the public, of course, was not impressed. They would come in the house, and they would see all this money she has spent, and this went on for a while, though she gave a couple of major parties that people seemed to enjoy a lot.

At that point, poor Willie fell ill, probably typhoid fever. The water in Washington was all polluted. They drank right out of the Potomac, and Willie — Tad to a less degree — fell ill. During one of their big parties, Mary Lincoln and a tired Abraham Lincoln stole off and went upstairs from time to time to nurse their severely ill child and try to bring him through it. And he got through for a few days, but then one morning, the secretaries in the office saw Lincoln come in bursting into tears. They said he said, “Boys, my Willie is gone. He’s dead.” The poor little boy, the brightest of the Lincoln family, had died. This was a blow to Lincoln and a blow to Mary Lincoln. She had her whole heart fixed on those children, whom she adored, and she simply could not get over the loss of Willie. The funeral was very sad. She was much too ill to go to it, and Lincoln buried his little boy in a mausoleum there in Washington but went back with Stanton, by the way, to have it opened once or twice. He just could not believe the boy was gone. Mary Lincoln never recovered from all this. She grieved so for the rest of the administration. She was cloaked in veils of black garments. You could hardly see her through that. She was so moved and so distressed, at one point Lincoln had to take her to the window and point down to the Potomac where there was an insane asylum, and he said to her, “Mother” — he called her “Mother” — “Mother, you had better get control of yourself, or you are going to have to be sent down there one of these days.” And she tried. She really did try, but she had had such losses. Coming on top of that, the assassination of her dearly loved husband — and she adored her husband — was just more than anybody could bear. She collapsed. Presently, her mind was not safe, and she lived a tragically unhappy life for the rest of her years.

Is there anything else you’d like to add about President Lincoln?

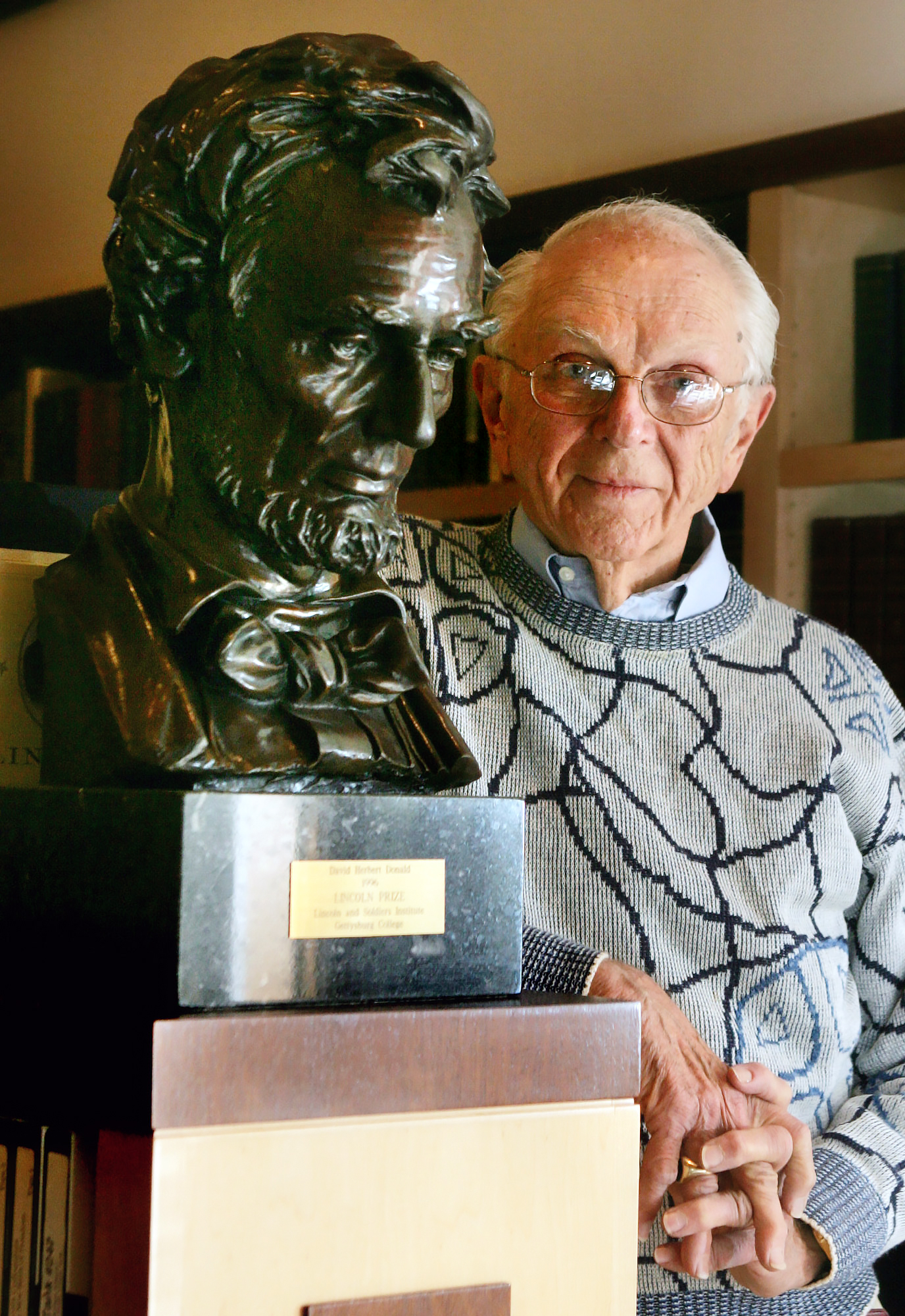

David Herbert Donald: Indirectly. One of my former students is just publishing a new book called Did Lincoln Own Slaves?: And Other Frequently Asked Questions About Abraham Lincoln. It is a wonderful, wonderful book. Of course, Lincoln never owned slaves. This has raised every conceivable question anybody has ever raised about Abraham Lincoln: “What was the size of his foot?” “What did he drink for breakfast?” Anything you can think of, and he answers them calmly, coolly, and often very funny. It’s a very amusing book as well as a very capable book. So we haven’t answered all those questions, but if we did, we’d be answering 350 pages of questions.

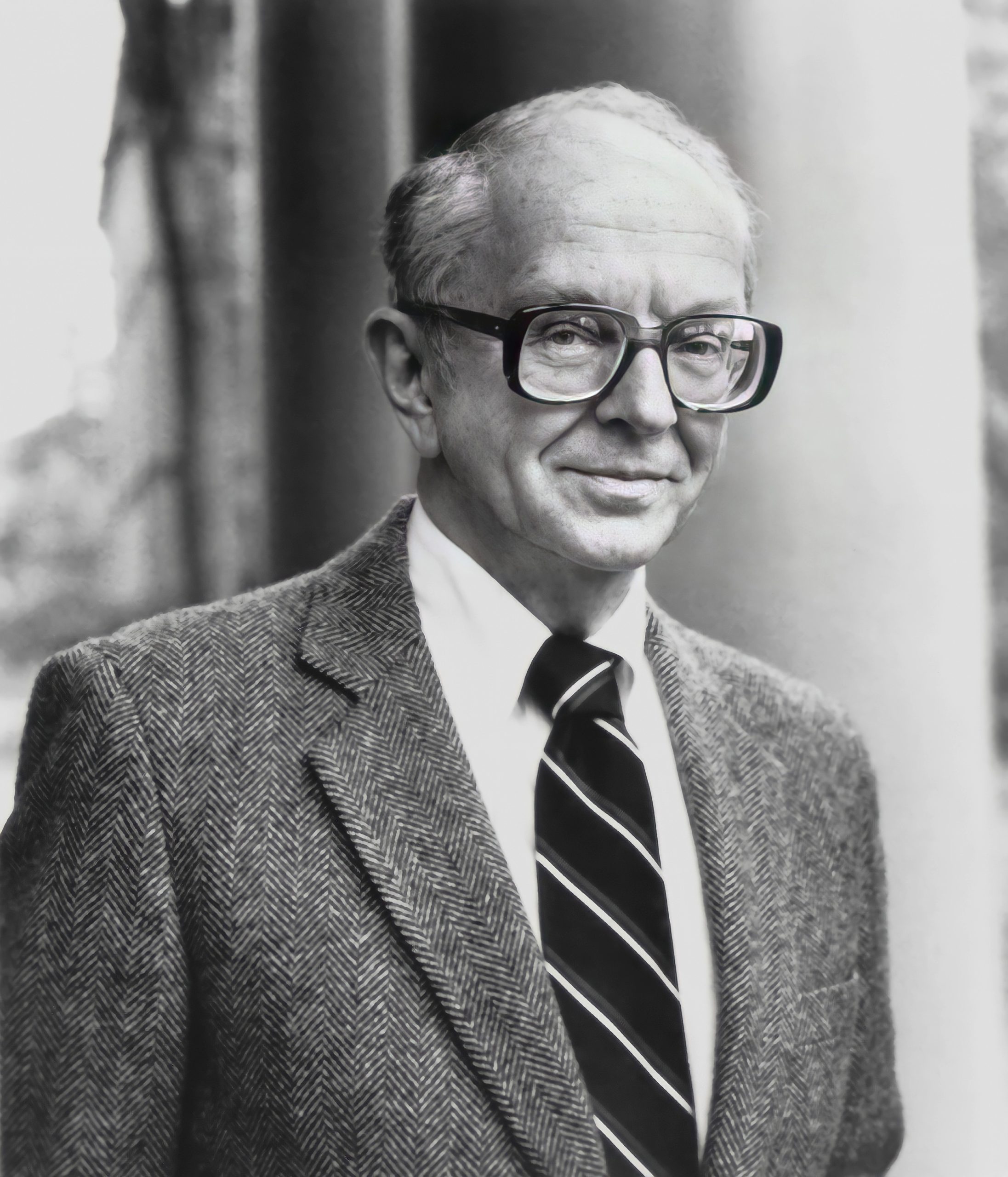

How did you first become interested in American history? You’ve spent your adult life writing about it. Was this an interest that started when you were young?

David Herbert Donald: When I was a little boy, I didn’t have access to a lot of books, but my mother had bought a series called The Real America in Romance. I don’t think anybody has heard of it since that time. It was about twelve volumes, and it was a beautifully illustrated narrative history of America from discovery down to whatever the present date was, maybe the 1920s. Looking back on it, it was sappy, it was sweet, it was altogether a story of triumph, but it was fun to read. And I learned a lot about the Aztecs and the Mayas and things like that as well as about American history. I think that got me interested in American history — trapped by American history, so to speak, and I have been with it since.

So when you were reading those books, did you think you’d want to be a historian, an author, and a history professor?

David Herbert Donald: I was pretty sure until I graduated from college that I wanted to be a band director. I played the clarinet rather well, if I may say, and my expectation was to get a job as a band director in some high school in Mississippi, where I grew up, and that would be my life. Maybe I’d teach social studies on the side. Well, I have a little story about that. Like Lincoln, I have a little story. It was summer. I was in my senior year. I heard of a job over at Indianola, Mississippi, which is in that flat delta area. It goes on and on and on, no hills, no anything, hot as Hades. I heard there was a job there. I went over to see it. I had no money. So I hitchhiked over there. I came — rather dusty I’m afraid, by the time I came to the principal’s office — but he seemed pleased to meet me, and we talked about the job and what I would be doing, would be teaching this, that, and the other, and there were a couple of things that bothered me about it. One was, as we went around, he said, “You will be leading the band, and the band is financed by this Coca-Cola machine.” I said, “Oh. I don’t think that’s very sound financing.” “Oh,” he said, “You don’t know Mississippi and Indianola in the summertime where it’s 100 degrees. That coke machine is a steadier source of income than the state taxes ever would be. You would be fortunate that it would be dedicated to you.” Well, that sort of took care of that. I went back to his office. He said, “Now if you come, you will want to find a place to stay. There’s a boarding house right up the street here. I will introduce you if you like.” I said, “That’s fine.” So he got up and collected his papers and such, and I got whatever little thing I had and followed him. He turned, and he said, “Where’s your hat?” I said, “I never wear a hat.” He looked at me, and he said, “You teach in my school, you’ll wear a hat,” and I decided I don’t want to be a high school teacher. So after that, I went off to graduate school.

When you decided to go to graduate school, were you just following your curiosity about American history or was there a goal in mind that you wanted to accomplish?

David Herbert Donald: When I graduated from college, I had no idea what to do, and I certainly had no skills that were marketable, and I heard about graduate school. I didn’t know anything about graduate school at all, what you did, except that it would be a substitute for a job. So I applied at, I believe, twelve different places. A little story about that: I went to Millsaps College, which is an excellent small college in Jackson, Mississippi, but it’s small. I had a professor that I leaned on a lot and loved, Vernon Wharton, an American historian. So I told him I had been applying to these twelve places. He said, “David, I’m glad to write for you, but I don’t have a secretary, and I don’t have the time. I cannot sit down and write twelve letters for you.” I said, “But I’m applying at twelve places.” “Well,” he says, “this is what I’ll do. You write the letters, and I’ll sign them, whatever you say about yourself.” So I went back to my typewriter, and I wrote twelve letters recommending me most notably. I’m kind of amused to say that ten of them got me fellowships. Well, a long time after that — one was the University of Illinois, which I attended — a long time after that, Illinois asked me back to give a lecture or some such thing, and we revisited and so on. And because it was a long time ago, and I hadn’t remembered everything, I had asked could a graduate student look over my graduate records, just to remind me what I had been doing when I was there, and he came up with something interesting. In my file there, there was a letter of application signed by Vernon Wharton and written by me, of course, and on the margin was a note of the dean. “Admit this man,” he said. “He has excellent letters of recommendation.” So I’ve always felt rather fraudulent, but I certainly enjoyed my years in Illinois.

Did your parents encourage you to pursue this career? Did they think you were a gifted child?

David Herbert Donald: I don’t think I was treated as a gifted child. I was hardly a spoiled child, in a large family of children. I don’t think they had any idea about a professional career as a historian and so on. It would be conceivable to take up a career as a lawyer. It would be conceivable to be a doctor, though that required more money than my father had to put into for one child. So the idea was simply the children got a good college education and they were on their own. All of us did different things. My one sister became a bacteriologist; my brother became an agronomist, and things like that. I didn’t really have any skills to do anything, except I’m a good typist, so the idea was maybe you should keep on going to school until you learn something.

Was there a particular book you read that inspired you in your high school or college years?

David Herbert Donald: There were several books that inspired me, one of which I don’t think I’d recommend particularly these days. But H. G. Wells’s Outline of History is a wonderful book that tells all about history from the prehistoric down to the present. And it, for the first time, gave me some perspective of where we stand: a very long history of the world and a very small segment. That kind of book did fascinate me a great deal, and perhaps it got me steered in the direction of history.

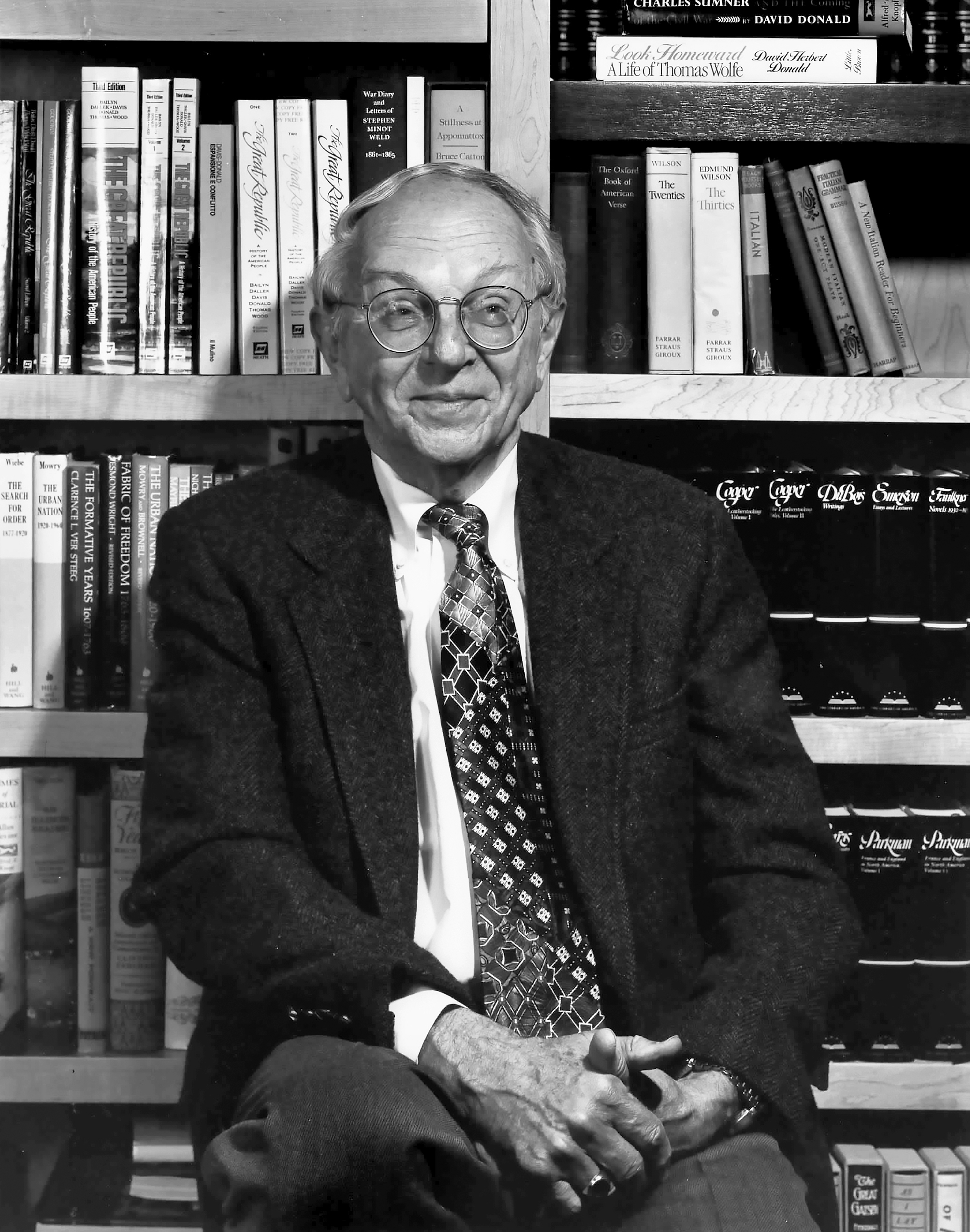

When I started graduate school, I had no idea that I would wind up studying Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War and such things. You don’t hear a lot about Abraham Lincoln or the Civil War in central Mississippi, you know. I just was going to school, as I said, to have something to do. I got to the University of Illinois where, fortunately for me, the great professor on the American history side was James G. Randall. Professor Randall and his lovely wife, Ruth Randall, took a liking to me, partly, I think, because she was very Southern, and I was very Southern, too, at that time, I guess. And they, in effect, virtually adopted me. I was at their house time after time for dinner, for supper, particularly if they took me to plays. They took me to movies. They treated me like an adopted child, and so when the chance came to be his assistant, a graduate assistant, I leaped at it, and even so, I had no idea what I was going to do. I just had it as a job. He was working on his big biography of Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln the President, and he needed somebody to check references and look up books and so on, and so I was doing that. After a year or so of that, Professor Randall came — I can’t remember clearly. He came stomping over to my apartment, saying, “You know, the time has come for you to think about a thesis subject,” and I said, “You know, I do think that’s right, but I don’t have anything.” “Well,” he said, “you have been working on Abraham Lincoln now for about a year for me, and you have accumulated a lot of information. It would be a pity for it to go to waste. So I suggest that you might want to write a biography of William H. Herndon.” Herndon was Lincoln’s law partner and biographer. His papers had just become available in the Library of Congress, and we had them on microfilm, and he said, “With what you already have, you can work on these papers and write a life of Herndon. It would also be about Lincoln.” And I thought, “Hey, that’s an interesting idea,” to sort of capitalize on what I did know. I worked on it. That was my doctoral dissertation. I was fortunate enough to have it accepted by Alfred Knopf first round, and they published it in 1948, and that sort of, can you say, trapped me in the Lincoln Civil War figure.

Would you say James Randall was the teacher who had the greatest influence in shaping your career?

David Herbert Donald: Professor Randall was a great advisor and a great mentor. He taught me, I think, in the best possible way. He was not a brilliant lecturer. His courses were fairly pedestrian. I didn’t think his seminars were particularly interesting. But working with him on a one-to-one basis as his assistant, I think that’s the way one has to learn to be a historian. That is, he was writing, and if he needed some particular reference, I had to go find it and get it. If he was writing, he wanted everything checked meticulously over and over again. So I had to take the manuscript over to the library and check it all out. So that by working closely with him, I got to see, first of all, a lot of the library and its extensive holdings, but I got, even more important, to understand what a scholar is about. It is about care. It is about “pains-taking.” It is about judgment as well as it’s about very skillful writing. He was an excellent writer as well. So in that sense, Professor Randall and Mrs. Randall shaped my future career.

As you see it, was there any connection between your background as a Southerner and the history of the Civil War era that you chose to study?

David Herbert Donald: There really was no connection with my growing up and my academic interest. I didn’t know what I was going to do when I went to graduate school, but I had a vague feeling that maybe I should write a history of Mississippi, my home state. That would give me something to connect with my roots, so to speak, and I thought about it for quite a while, and then I realized I don’t know much about Mississippi, and my own training experience was very meager. I lived in a town of 680 people, half white, half black. My knowledge of the broader aspects of Southern history was very skimpy. So that I decided that’s not for me. I’d better stick to something where Professor Randall knows a lot and can help me find something that I can learn a lot about.

Does it matter that I was a Southerner? Yes, I think it does, and in a certain sense, I think the fact that I grew up in the South, the Deep South, has contributed to the fact that I am, as you can judge, a nonstop talker and storyteller, and Southerners tend to be. This, I believe, was a help in my early books because when most people are writing a dissertation, it’s like an abstract or a recipe. I sort of spread myself, and I told stories, and people found it interesting. One of the people, a great professor of mine — after oral exams — read the dissertation. He said, “Mr. Donald, I see that you are trying in some places to write very well and to reach a large audience.” I said, “Well, yes, I would like to do that.” “Well,” he said, “I don’t think that’s to be encouraged. I have a rule.” He says, “When I have written anything that I think is clever or witty or striking, I always go through and rub it out. You should do that.” And I said, “Well, maybe that’s what I should do.” And then he said, “After all that, I really enjoyed reading your thesis, and I usually don’t.” So I thought, “Well, okay. Maybe I’m hitting on something here.” So I think something, in that sense, had something to do with it — also, the fact that I grew up in a “half white, half black” environment. I’ve always found African-American people perfectly happy to be associated with me and vice versa. I don’t have any race prejudices whatsoever, and this has made it a lot easier for me to talk about the South, to talk about racial relations, to talk about civil rights than perhaps some other people who have fixed ideas on these matters.

If you were speaking to someone who knows nothing about your field, how would you explain what makes it so exciting to you?

David Herbert Donald: American history is exciting, first of all. We are really the only modern nation whose entire career in our history is available to us. That is, we can go over the first papers, the settlement of Jamestown, all the way down to the present, and the documents are there. There are no mysteries about it. If you were writing about the history of England or Sweden or so on, you’d have to go back in the depth of time and still wouldn’t know how things began. So in America, you have a kind of case study of the development of a nation and how it grew and why it grew and why it grew in this particular way, and this has always had a special fascination for me. With the Civil War, it is, in particular, the fascination of two roads. One might have led to an independent Confederacy, two nations on this continent. What would have happened since that time? So it encourages you to imagine things were different, and the other was the road that was taken. So one puzzles over these aspects and tries to figure out, “What can I do with this? What can I make out of it?”

You spoke about being Professor Randall’s research assistant when you began to write your dissertation in the 1940s. Were you already shooting for a Pulitzer Prize? What were your goals then? What motivated you?

David Herbert Donald: My ambitions as a graduate student were quite modest. I hoped that someday I’d get a Ph.D. That with a dissertation that was acceptable, I might get a job teaching at Illinois College in Jacksonville, Illinois. It’s a lovely little college, right near Springfield, but not too close, 40, 50 miles. It has good, high standards. It is a wonderful place for undergraduate education in the Middle West. It is sort of the Middle West equivalent of, say, Amherst, maybe Williams, and that was my aspiration. It never occurred to me that I would go on to a university, that I would go on to write books that people would read and so on. I was just looking for something quite local. There is a postscript here, that a couple of years ago I had the great fortune to be given an honorary degree from Illinois College. I went out there, and loved it, and reminded them that this is the career that I almost had. But I did not start out like Abraham Lincoln with “a little engine that had no rest” as my ambition. I started out thinking, “Well, maybe I can make a reasonable living teaching at Illinois College.” One thing led to another, and I got a traveling fellowship from the Social Science Research Council. It was to allow me to investigate sources in many parts of the country, and I traveled a lot, mostly by bus, from Boston to Los Angeles, and did visit all the major libraries, and learned a lot from them, and wrote up a good long report of what I had found. Somehow or another, this report went to the Social Science Research Council, and one of their members picked it up and said, “You know, this is an interesting young man, been out doing all these things. Why don’t…” — he taught at Columbia — “Why don’t you bring him to Columbia? He would be kind of fun to have around.” So then I got a letter in the mail asking how I’d like to teach at Columbia, and I said, “Oh sure, I would.” So off I sped to become an instructor at Columbia University. Such a thing would have been absolutely unimaginable to me when I entered graduate school, but I think it was a fortunate break.

You won your first Pulitzer Prize in 1961. Was that a surprise to you?

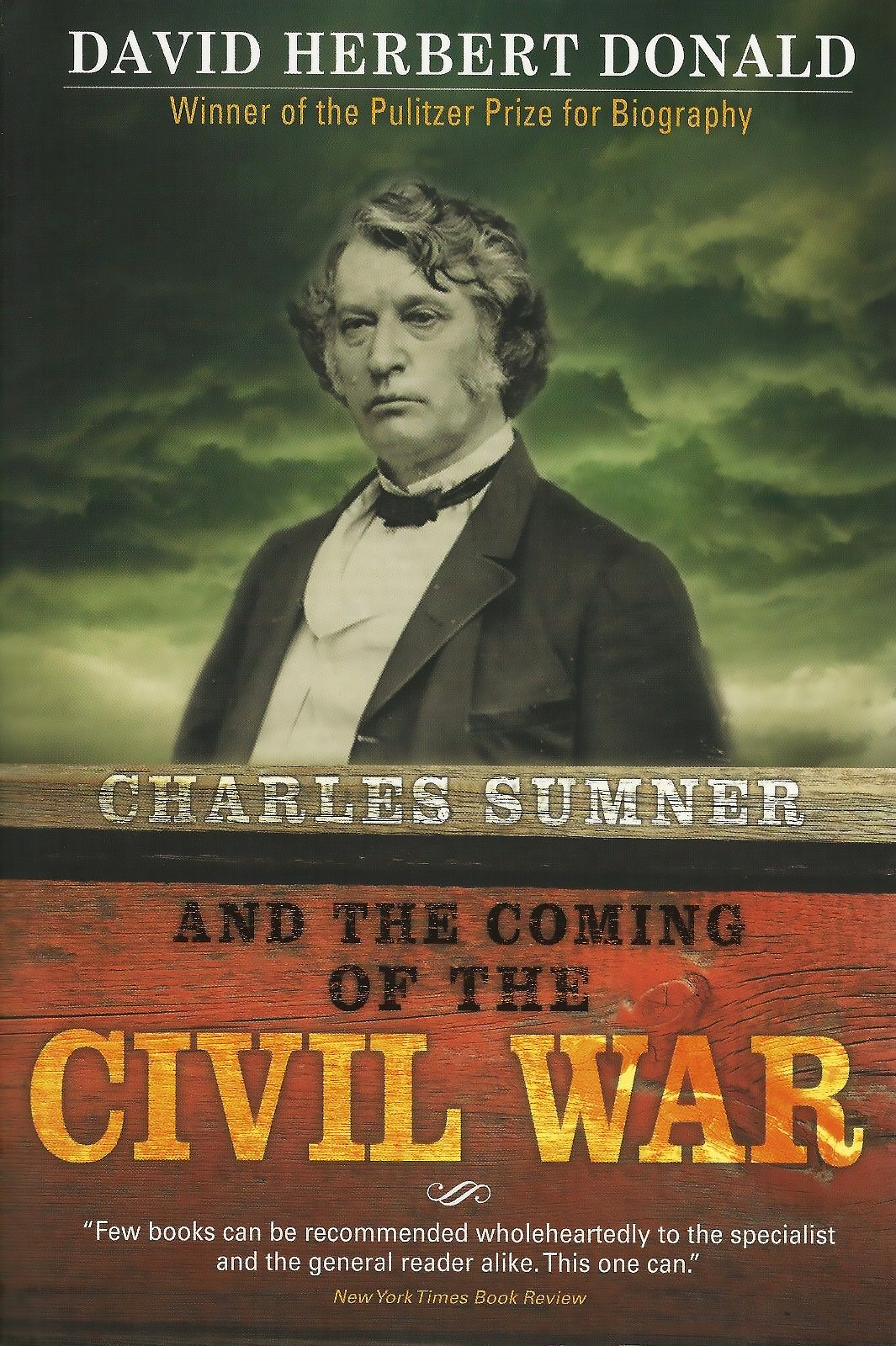

David Herbert Donald: My first Pulitzer Prize was for my first volume of Charles Sumner, the Massachusetts abolitionist. By that time, I had been working for some time on it. I was very much surprised. The book was supposed to be one large book, but I had been given an appointment in England to teach for a year. I talked to my publisher about it, and he said, “Look, if you stop for a year, you’re going to find it very hard to come back to the subject and finish it. Why don’t we publish what you have finished? And then you come back and you start the second volume.” The first of what I had finished ended with the outbreak of the Civil War, and therefore, it formed a kind of unit. And so I said, “Great, let’s do that,” and they published that book, Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War. It never occurred to me, honestly, that it would win a Pulitzer Prize because no one, no single volume in a series, had ever done that before. Nobody had ever taken volume one of a multi-volume series, and I was just astonished. Pleased and delighted, of course, and I did get back to Sumner, and I did go back and write a second one, a rather long one after that. But on the whole, I think historians don’t, by and large, work with a view of prizes and rewards. If they do, they’re nearly always going to be disappointed. My great editor at Simon & Schuster once told me, “These prizes are so political that nobody can count on them going one way or another. So nobody should set his heart on them,” and I never really had, to tell the truth.

It sounds like you didn’t start out with a big grand plan, but you seized opportunities when they arose. You created opportunities. Did you always think large achievements lay in your future? Or did you find yourself struggling at some point during your career?

David Herbert Donald: Well, somehow or other, I always thought of myself as rather special. Who doesn’t? But it never occurred to me that one day I would be an ancient historian being interviewed for television! I was just going to be, I hoped, a good college history teacher, and then things sort of broke for me. I started teaching in Columbia in the influx of GIs from World War II, and they needed extra people. So they had hired me, and I liked it there, and it turned out that they liked me, and the students liked me. So again, I thought of this as a very temporary kind of thing. Mrs. Randall kept the letters I wrote during those years, and one of them says, “You know, I am enjoying New York a lot, and I like living here, but I can’t imagine living here for any length of time.” I assumed that when my two-year contract was over that I’d go back maybe to Jacksonville, Illinois, but they needed people, and apparently, I filled the bill. I still was so uncertain about the future, though, that when Smith College was looking for a professor and they wrote down to Columbia and asked if I’d be interested, I said yes. So I resigned at Columbia and went off to Smith. The people at Columbia were baffled by this. They said, “Why would you leave Columbia to go to Smith?” I said, “Well, I don’t belong in Columbia. You know that. I’m very different from the rest of you. I’m going to Smith,” and they were angry that I had spurned them, so to speak. I went to Smith, and while I liked the students individually, it clearly was not for me. And in the second year there, I was fortunate enough to be asked would I go to Princeton, would I go to Yale, or would I come back to Columbia, and I didn’t know Princeton or Yale. I thought I’ll go back to Columbia, where at least they know who I am, and so I went back to Columbia and at that point decided, okay, I guess I’m going to make a career as a historian and tried to do so.

All modesty aside, what contribution do you feel you’ve made to your field, and what was the most exciting moment in your career?

David Herbert Donald: I don’t know how anybody judges the contributions he’s made to a field. I can tell you that my largest contribution — I’m sure the most lasting one — is my graduate students. I began having graduate students at a very early age and continued until my retirement. And ultimately, I had between 70 and 100 graduate doctoral students, of whom 50, at least, have published major books. Many of these were dissertations that they did under my direction and then published, and these students are now major professors at major institutions all over the country. I can think of myself as, in a sense, a kind of a Johnny Appleseed, spreading the word, so to speak, in a lot of different places. I believe I am right in saying they are all fond of me. I am in touch with them all. I write to them. I think of them frequently. I think of their children as being my intellectual grandchildren, and in a few cases, I have actually taught their grandchildren, which is nice, too. Now, was there any particular moment that I would say, “This is the peak of my career”? In a sense, it was. By that point — this is 1960 — teaching at Princeton; vacation was just over. We came back, and I was meeting my class all over again. It was a sizable class — 200 students, something like that. And I enjoyed lecturing; I enjoyed talking. I liked these students. I liked talking to them and so on, and we were going along one day after another, and one morning, I came in. As I came in, every student rose and started clapping. They had just heard that I had won a Pulitzer Prize, and I hadn’t heard it myself. I was just overwhelmed, and I think that may have been the high point of my career.

That’s a good one! You had some serious decisions to make, about which opportunities to take, but did you encounter any major obstacles or setbacks in your career?

David Herbert Donald: I have generally had few setbacks and few obstacles. I have been very fortunate in that things have been handed to me rather than my going out after them. There are a few roads that I didn’t take that I maybe could have. When I was a graduate student, maybe a second-year graduate student, I worked frequently at the Illinois State Library in Springfield, and one day, the director of that library called me into his office and said, “I have some news to tell you that is still very hush-hush, but I’m resigning from this job. I’m going to the Chicago Historical Society, and I’m going to recommend that you be appointed in my place.” I was stunned. A second-year graduate student! I hadn’t published a thing and suddenly to have this dropped in my lap. And I thought about it. I was like, you know, this is a real opportunity, but I don’t think it’s for me. I’m not the administrative type. I don’t like to run things. I don’t like to boss other people. I just like to be on my own. So I said, “I think I’d better pass on this, though I am deeply grateful for it.” So that was one path that wasn’t taken. A little later, I was teaching at Columbia, and I got a phone call from the Abraham Lincoln Association in Washington, D.C. It was the Lincoln Bicentennial Commission, and the spokesman was Daniel Boorstin, who was working in that commission at that time. “David,” he said, “there has been a change in the Bicentennial Commission here. We need a new director. Would you like to do it?” I thought to myself, “I don’t want to do this sort of thing. This is a public relations kind of job. It is in Washington. You deal with all these senators and congressmen trying to get appropriations.” I said, “This isn’t for me at all, Dan. I just really don’t want it,” and so they went to somebody else. So there have been careers that I didn’t take, really quite deliberately. I stuck to a fairly narrow career, and I have enjoyed it.

You’ve had a prolific career as a published author, so you must have encountered criticism. Is there any difference between how you handled criticism in your early years and how you took it when you were older?

David Herbert Donald: In my early years, I got almost no criticism. This was in part due to the fact that I was young, and people tend to be kind to young people, but it also had some other factors as well. I was writing my book on Herndon, which was my first published book, and Professor Randall sponsored that as a dissertation and read the manuscript for me. That summer, I encountered Carl Sandburg at the Library of Congress, and he read the manuscript and liked it and volunteered to write a foreword for it. So when the book came out, Orville Prescott, who was then the reviewer of The New York Times, said, “I don’t know how to review this book.” He said, “It’s endorsed by the two greatest Lincoln people in the country. J. G. Randall is a noted scholar, Carl Sandburg is a noted poet, and they both say that it is good. So I have to like it.” And then he goes on to say, “I really did like it, anyway.”

I generally had a very easy life. This doesn’t mean that I have always been easy in my own criticism. I used to write enormous numbers of book reviews, many of them sharp. Perhaps I was trying to bring people up to my standards. Perhaps I was just young and acerbic. Anyway, over the years, I came to think that’s not the best way of encouraging people or even discouraging people. So I tend either not to review books that I don’t like, if I already know I’m not going to like them, or to review more generally, putting it in some kind of broader context, and that has been my tone for the last 25 years.

As far as criticism I’ve had in these years, there’s been some of it, and some of it is kind of interesting. One argument is that I’m an apologist for the slave society of the South because, after all, I am a Southerner. Things like that. I haven’t let them bother me, and I really don’t. Every now and then, somebody comes up with something that sort of tweaks the record a bit, saying that this is a man who wrote a two-volume life trying to demolish Charles Sumner and show he was mad. This is the one time I wrote to the Times, saying, “Why did you publish that? I have never written anything like that about Charles Sumner.” And I give a quotation: “He’s one of the great men of the time.” “I don’t know why you did this,” and they agreed. “We don’t know why we did it either. It was a mistake.” But mostly, criticism doesn’t affect me much.

Do you see any changes at work in the method of teaching and researching American history? What do you think is the next great challenge?

David Herbert Donald: American history has already changed so very much. I look back on my own career, and believe it or not, when I was teaching at Columbia, I used to give two-hour lectures on the nullification controversy in South Carolina, and believe it or not, I knew everything about it at that time. Don’t ask me now. I don’t know anything about it. That kind of close political history has almost disappeared. Instead, now we have a psychological history, much of which is very good. We have women’s history, and we have minority history, especially black American history. So the subject of history and the subject of historians has already changed a great deal, and you differ as you write about these very different subjects. I don’t dare to write about women or women’s history because I am not sure a man is able to write about women’s history, and I have never written anything significant about black history because I suspect that only blacks are capable of writing and understanding black history. But these are frontiers that the next generation is going to have to deal with, and I hope we get some masterworks out of them.

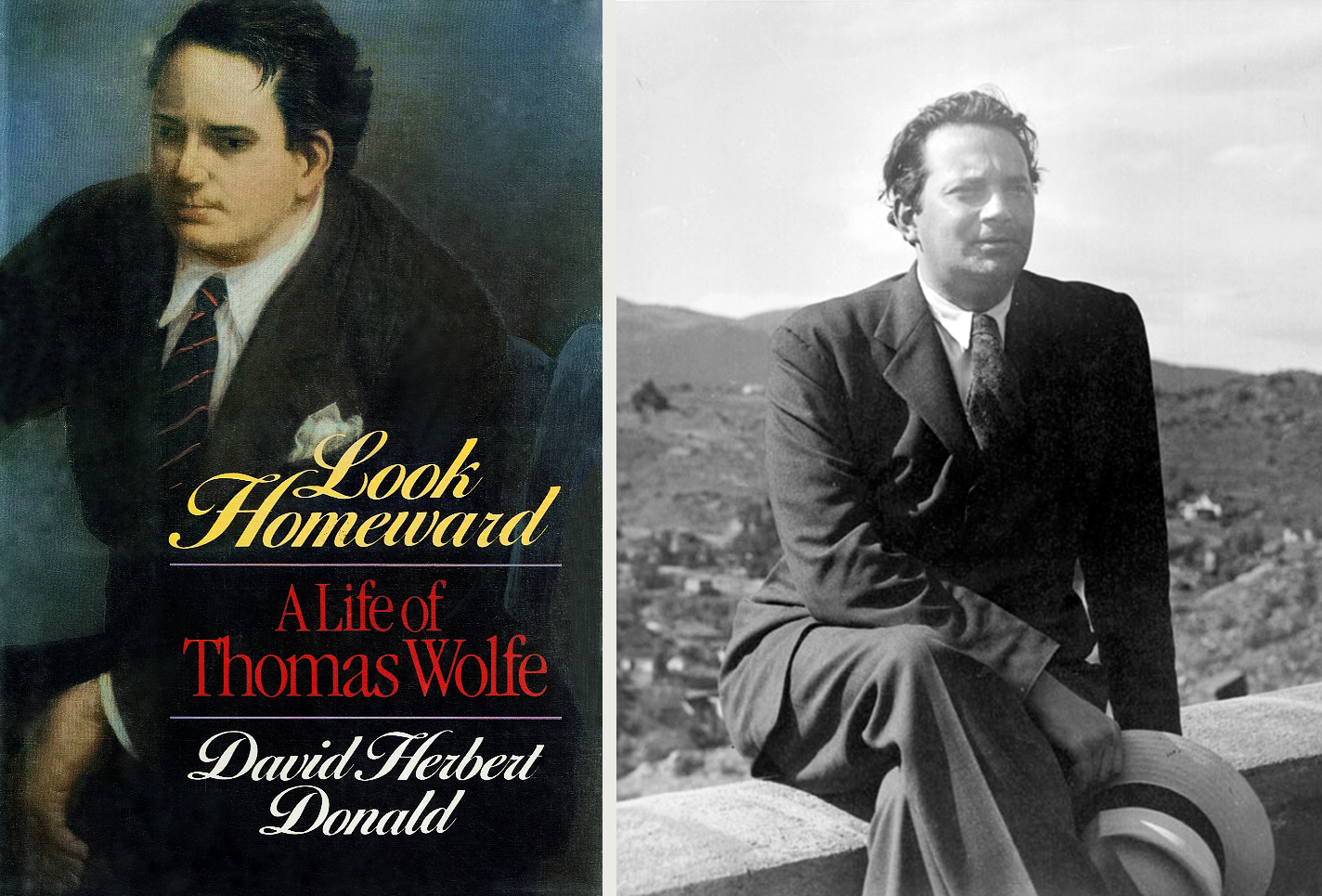

In the 1980s, you took a different direction and published a book about the novelist Thomas Wolfe that earned you a second Pulitzer Prize.

David Herbert Donald: My biography of Wolfe was something of a surprise to everybody, perhaps including myself. I had finished several Lincoln books about aspects of Lincoln in the Civil War, and I thought to myself, “I don’t think I want to do that again, right now anyway,” but what would I do? About that time, we decided we’d go on vacation in North Carolina. There are wonderful areas out there in the western mountains, and we enjoyed it immensely. And driving back from the mountains, we went through Asheville, and I thought, “You know, we ought to stop there and see Thomas Wolfe’s house,” which I had seen once before, but my wife never had, and so we did. We went through that house. It was a very impressive old house, in a sense; it was huge. It was, indeed, as Wolfe’s father said, “a damned old barn.” It was practically empty, all these little cubicles with a light hanging down by a cord in the middle of it, a narrow, flat bed, maybe one bureau and a chair. That’s all it was furnished with. People came to rent rooms there because of the mountain air, and Julia Wolfe made a living for the family by renting. And I thought to myself, “Isn’t it odd that Thomas Wolfe, who writes the most luxuriant prose of any American, so full of description, so full of wonderful language, should emerge from this absolutely barren background?” And I told my wife, I said, “You know, somebody ought to do something about Thomas Wolfe.” And she said, oh yes, I ought to, and we drove home.

It sort of buzzed in the back of my mind. I came back to Harvard, where I was teaching at that point, wondering what I was going to do, and I thought, “I wonder where Wolfe’s papers are?” I began looking at it, and they’re all in Houghton Library at Harvard, and I thought, “Well, this is quite unusual.” So I go over to take a look at them, and I asked the curator of manuscripts, “Will you show them to me?” He took me to that wonderful building, and you go down two floors, deep into the subterranean vault, all air-conditioned and all that sort of thing, and there are rows and rows of black boxes of papers and so on. He took me to a wall that stretched probably, oh, we’ll say really the length of this house that we’re in now, as far as you could see. “Those,” he says, “are Thomas Wolfe’s papers,” and I said, “You’ve got to be kidding.” “Yes,” he said. “He never threw away anything.” And that is true. I thought I heard him say, “Three to six million pages.” He later said, “I didn’t really say all that, did I?” But there was a lot of paper there. And I thought, “Okay, this is something I can do while living in Lincoln, Massachusetts. This is a subject I’ve been interested in. It’s a change from Abraham Lincoln. Why don’t I do it?” And so I set to work doing Thomas Wolfe, and it was quite a change. I had to teach myself something about literary criticism, about deconstructionism, about a number of matters that I had not previously dealt with. So it was an educational process for me, and I loved it! I liked the people who worked on Thomas Wolfe. They were all very helpful. So Thomas Wolfe emerged from that.

In 1988, when you received your second Pulitzer, it was 27 years later. You were a different person, with a lot more experience under your belt. Was it a different experience, receiving your second Pulitzer?

David Herbert Donald: Well, it necessarily is. After you’ve done it once, the second time is wonderful, but it’s not quite the excitement of the first one.

Is there something about achievement that you know now that you didn’t perceive as a young person?

David Herbert Donald: When I talk about achievement, I tend to use flat, much-too-frequently-used phrasing, namely, that you have to work hard. I think most people don’t realize that writing is very hard work. It doesn’t come easily to anybody. Then you have to revise and work over, over, and over again. Second, it requires a lot of time to research what’s behind all of this before you start writing. And third, it requires what I think many of us do not do: a lot of thinking. What does this all add up to? Why am I writing about this person? Why is he worth my time? That’s hard to answer sometimes. You could mine a subject and wring a book out of it, but unless you’re sure in advance that it’s a major subject for you, it’s probably not worth all the close attention and hard work it’s going to take.

We often ask our honorees for their definition of the American Dream. What does the American Dream mean to you?

David Herbert Donald: The American Dream is one of those loose phrases that we use in too many contexts, I think. But by and large, Americans have had similar aspirations: aspirations to be free, aspirations not to be meddled with, not to be told what to do, aspirations that mean the whole future is ahead of you. You can do all sorts of different things and you don’t necessarily have to do what you were slated to do in the ninth grade or the twelfth grade or the first year of college. The world is really open to you, and there are so many choices that you can make. And in many cases, you will do as well in one choice as another. You’re not sort of fixed from the beginning: I’m going to be a scientist; I’m going to be a historian; I’m going to be a farmer. You probably could be good in all three of those roles, but you have to choose between them.

You’ve spent your career examining America’s past. Looking ahead, what do you think will be one of the big achievements in the next quarter century?

David Herbert Donald: Gosh. I wish I could predict what the greatest achievement in the next quarter century is going to be. I can predict what I hope it will be: a new source of energy. If we do not find for this world, this globe, a new source of energy, we are going to be running out very shortly. We already see shortages in many different areas. We need sources of energy to take care of our water supply. Atlanta, Georgia is really perishing for lack of water. We need sources of energy for our cars, or else we’re going to be back to traveling on foot or bicycle. We need sources of energy for faster communication, and these have to be devised, not something immediately in sight, where we can say, “Oh well, that’s going to come in ten years.” We’ve got to spend a good deal of thought and care in producing that. It’s got to be a revolution as great as the Industrial Revolution was in its time.

Thank you, Professor Donald, for a wonderful interview.