The big lesson for us is that all you have to do is spend a moment holding the hand of the person you love as she’s dying—and wishing, praying for another minute, another second, another month—to realize that if you get it, you’re not going to waste another moment with anything that’s irrelevant.

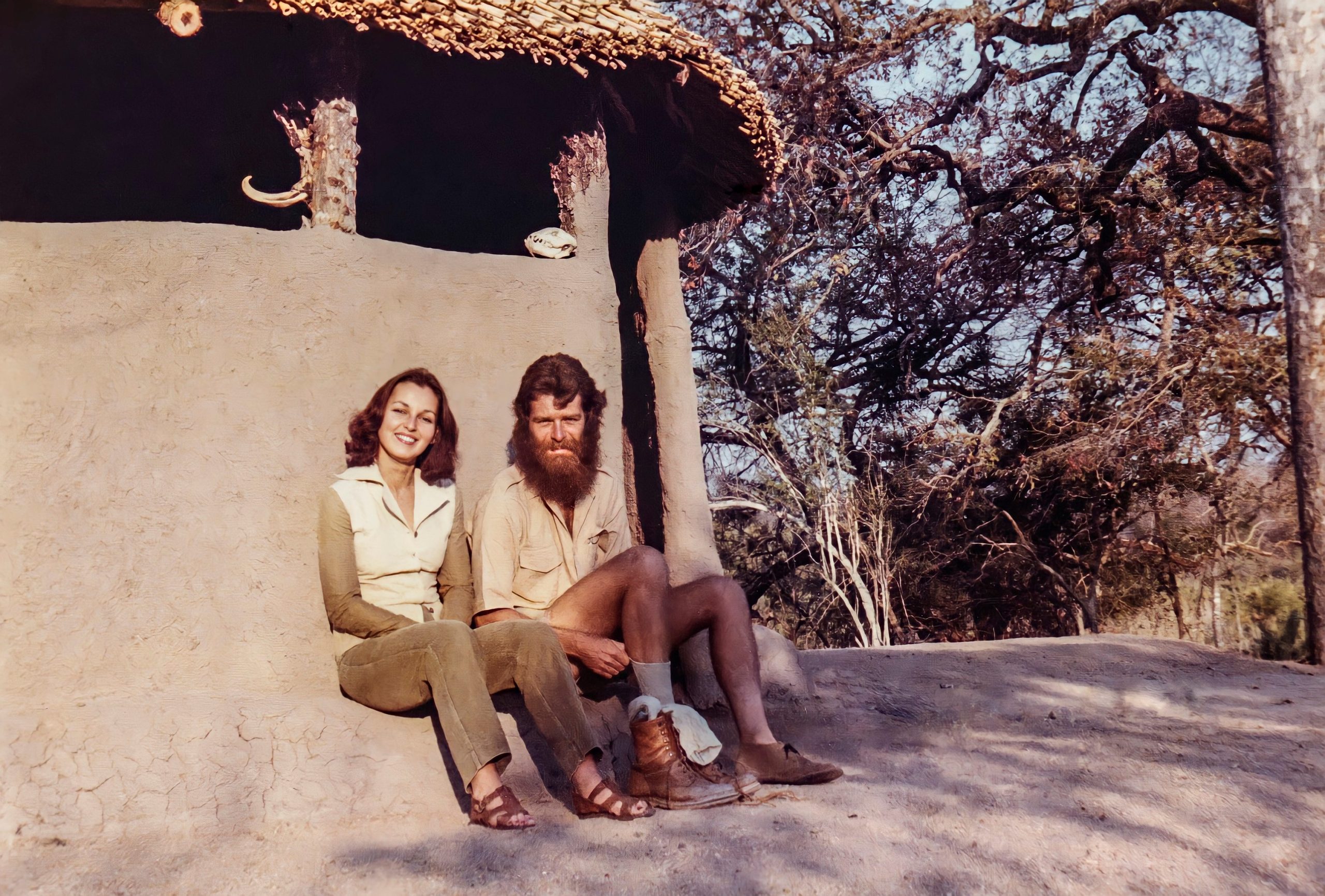

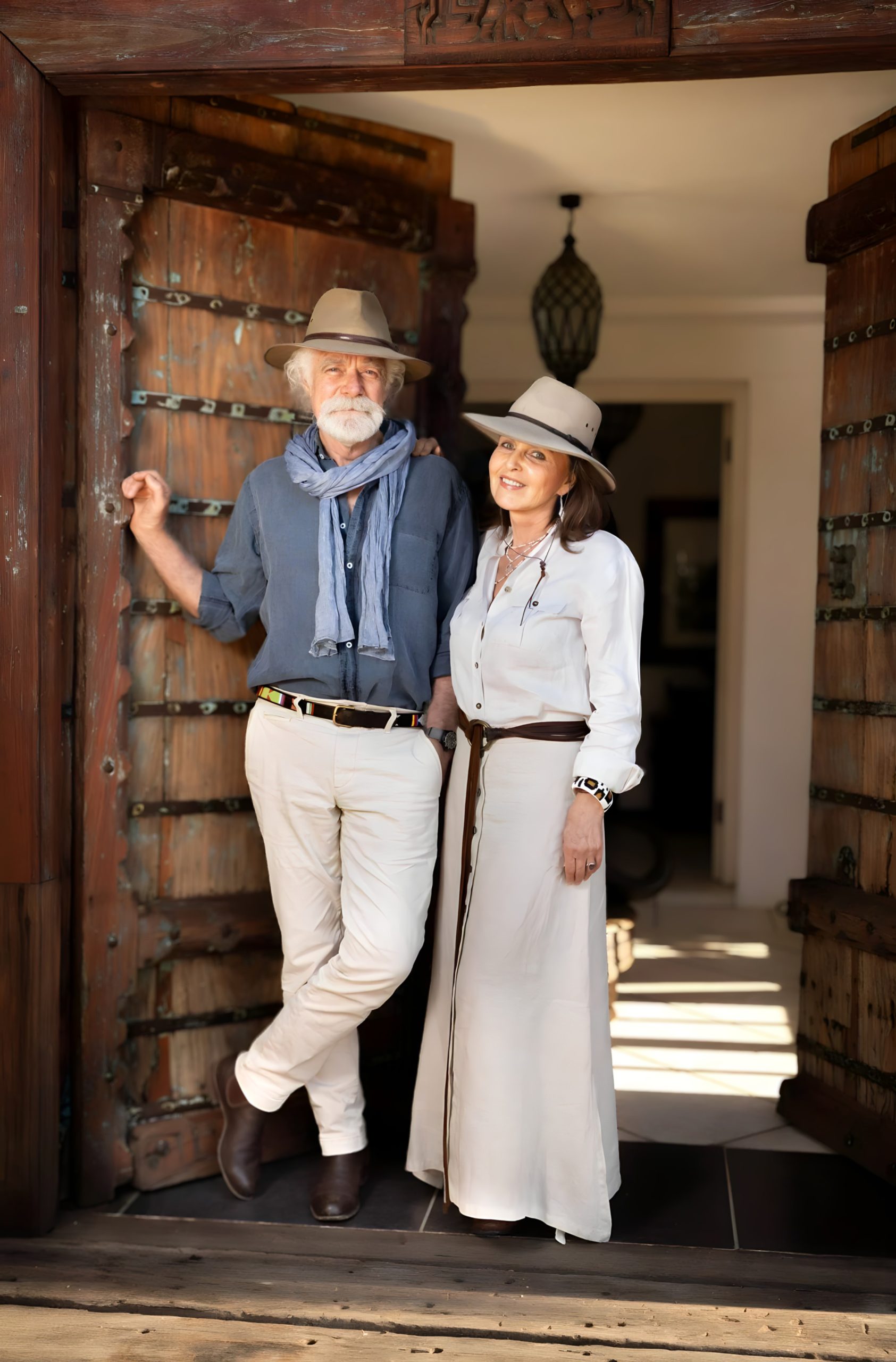

Dereck and Beverly Joubert were born a year apart in Johannesburg, South Africa. Although they met for the first time in high school, their first date would not occur until Dereck had returned from compulsory military duty in the South African Army. Once he had fulfilled his commitment, Dereck had no interest in further military service, but the survival training he had received would serve him well in his future career.

Dereck studied geology, and Beverly business, but the couple shared a greater passion. What motivated them above all was their love of nature, a passion for the landscape of unspoiled Africa and the fascinating creatures of the wild. Early in their relationship, the pair lived in the Eastern Transvaal, where they could explore nearby Kruger Park, one of Africa’s largest game reserves. Although they enjoyed observing lions and elephants on excursions from the park’s safari lodge, a holiday trip to the neighboring country of Botswana was a revelation. Canoeing in the delta of the Okavango River, they found themselves in true wilderness. This was the life they wanted for themselves, and they decided to make a life for themselves in Botswana.

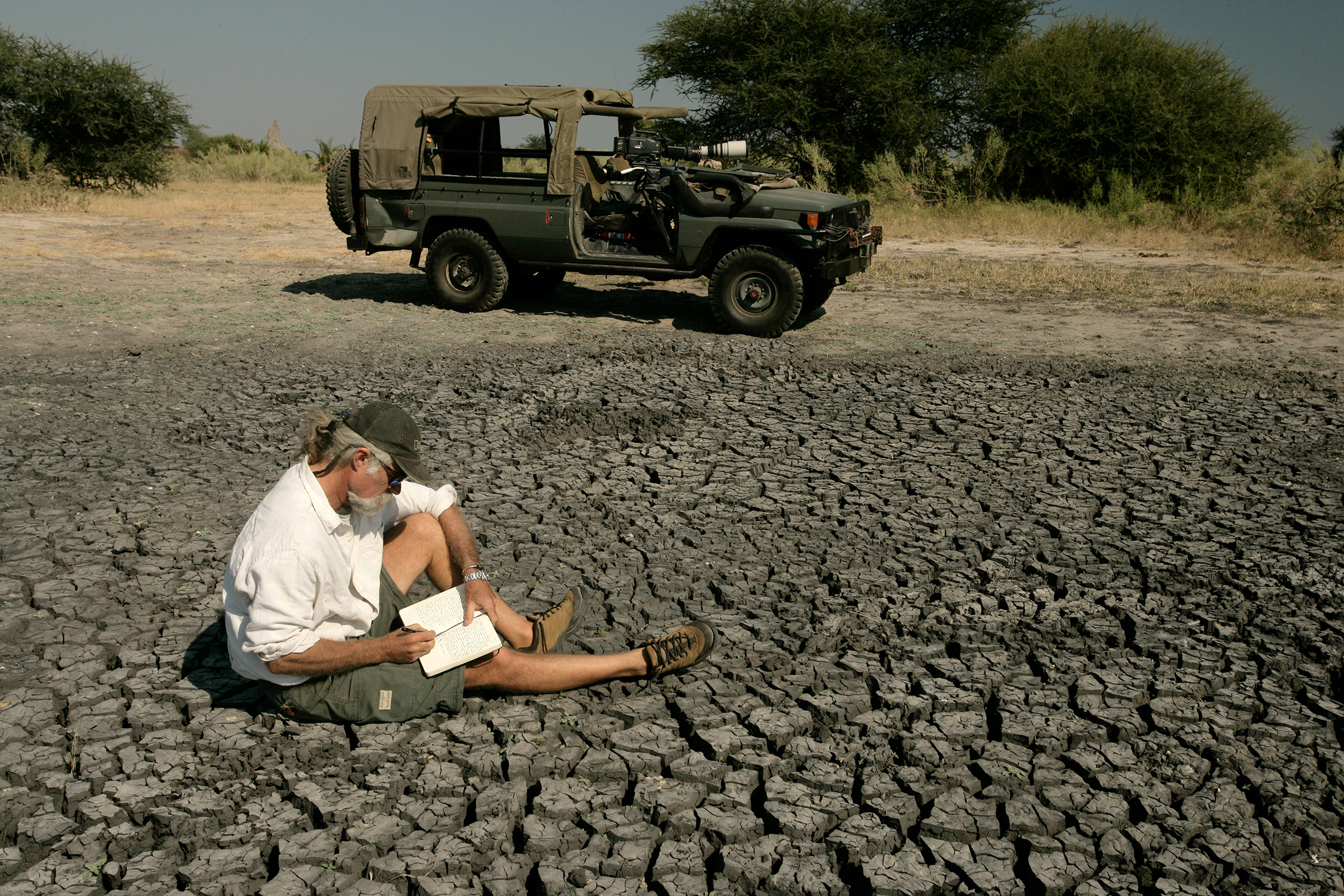

The couple, who married in 1983, joined the Chobe Research Institute, a conservation center in Botswana, and set to work observing the nocturnal movements of a pride of lions. They outfitted a truck and mastered the skills of surviving in the wild for months on end. They learned to live and work in their truck between campsites, suspending a tank of water from a tree to shower in the open air.

In an area they were studying, the principal water source, the Savuti Channel, was drying up, a situation that intensified competition among the area’s wildlife. To their astonishment, the Jouberts repeatedly witnessed a pack of 40 to 50 hyenas battling with a pride of roughly 30 lions. These ferocious struggles, which took place under cover of darkness, upended the conventional wisdom of natural science. Hyenas were thought to be cautious scavengers, not combative predators, and lions and hyenas had been observed to coexist peacefully by day. The Jouberts knew they would need photographs and motion pictures to document what they had seen.

Enthusiastic amateur photographers, they now became professionals and equipped themselves with the necessary gear for night photography and film editing. Dereck worked as a cameraman in advertising to raise money for their filmmaking project. In the field, Beverly recorded sound and took still photographs while Dereck handled the movie camera. It took many years to assemble their footage of the combat between lions and hyenas into a finished film, but in the meanwhile, they were collecting breathtaking footage of other creatures in the wild, and their work attracted the attention of the close-knit international community of wildlife photographers.

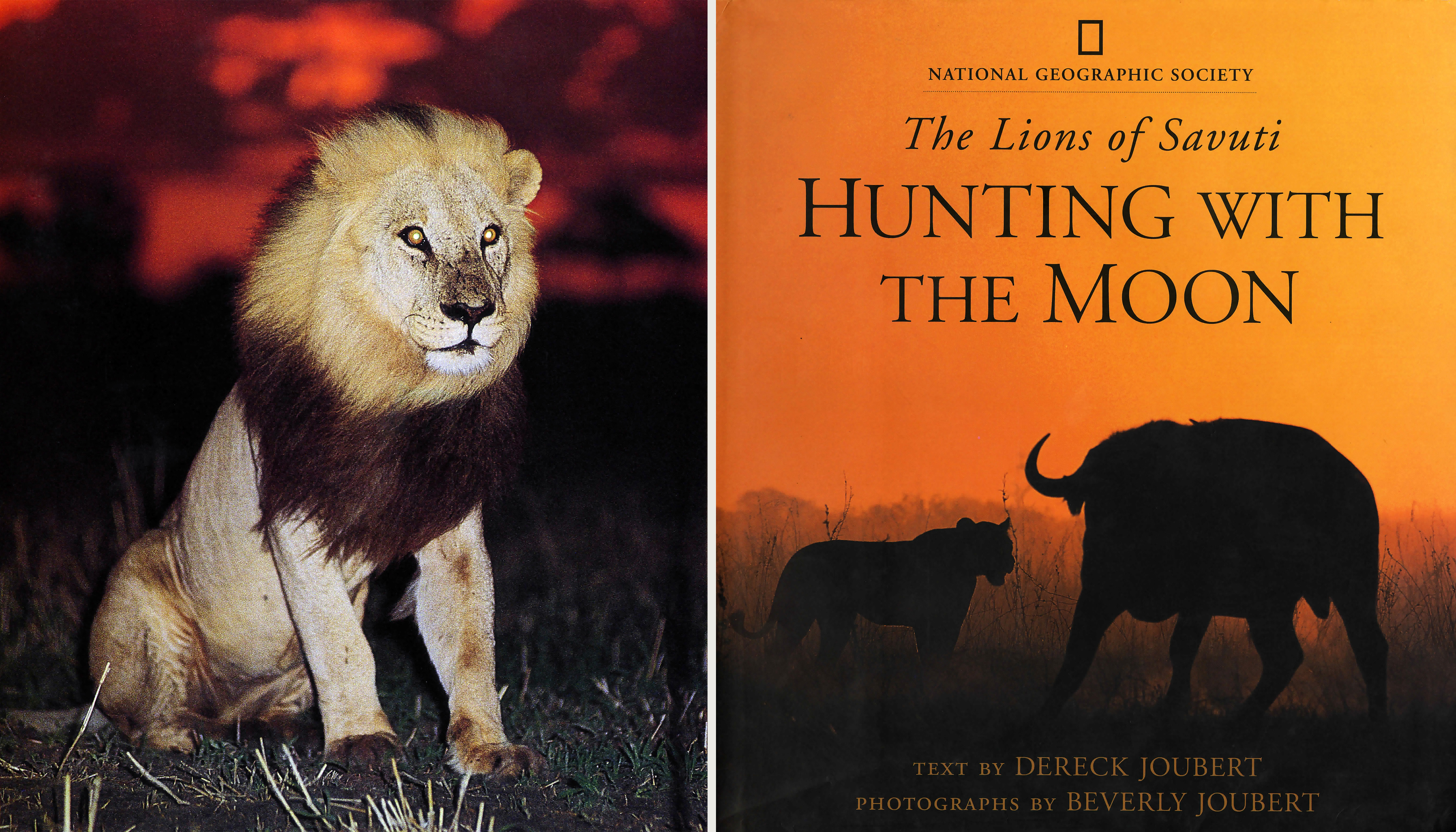

In 1988, they completed their film Stolen River, recording the disruption of the Savuti Channel ecosystem. Stolen River aired in the United States as a National Geographic Special on the Public Broadcasting System in 1988, the beginning of a long partnership between the Jouberts and the National Geographic Society. They continued the story of the displaced animals of Savuti in Forgotten River (1990). Their next films, Trial of the Elephants and Patterns in the Grass, aired on the Turner Broadcasting System. In 1992, the Jouberts completed the documentary that won them international renown. Since its release, Eternal Enemies: Lions and Hyenas has been shown in 127 countries, and it is estimated that this powerful film has been seen by more than a billion viewers.

To date, the Jouberts have created 30 films for National Geographic and published more than a dozen books, and Beverly Joubert’s photographs have been exhibited in galleries around the world. They have been profiled on television programs such as 60 Minutes, and their films have received eight Emmy Awards and a Peabody Award. They have been named National Geographic Explorers in Residence, alongside Sylvia Earle and Richard Leakey, and have received the Presidential Order of Merit from the President of Botswana.

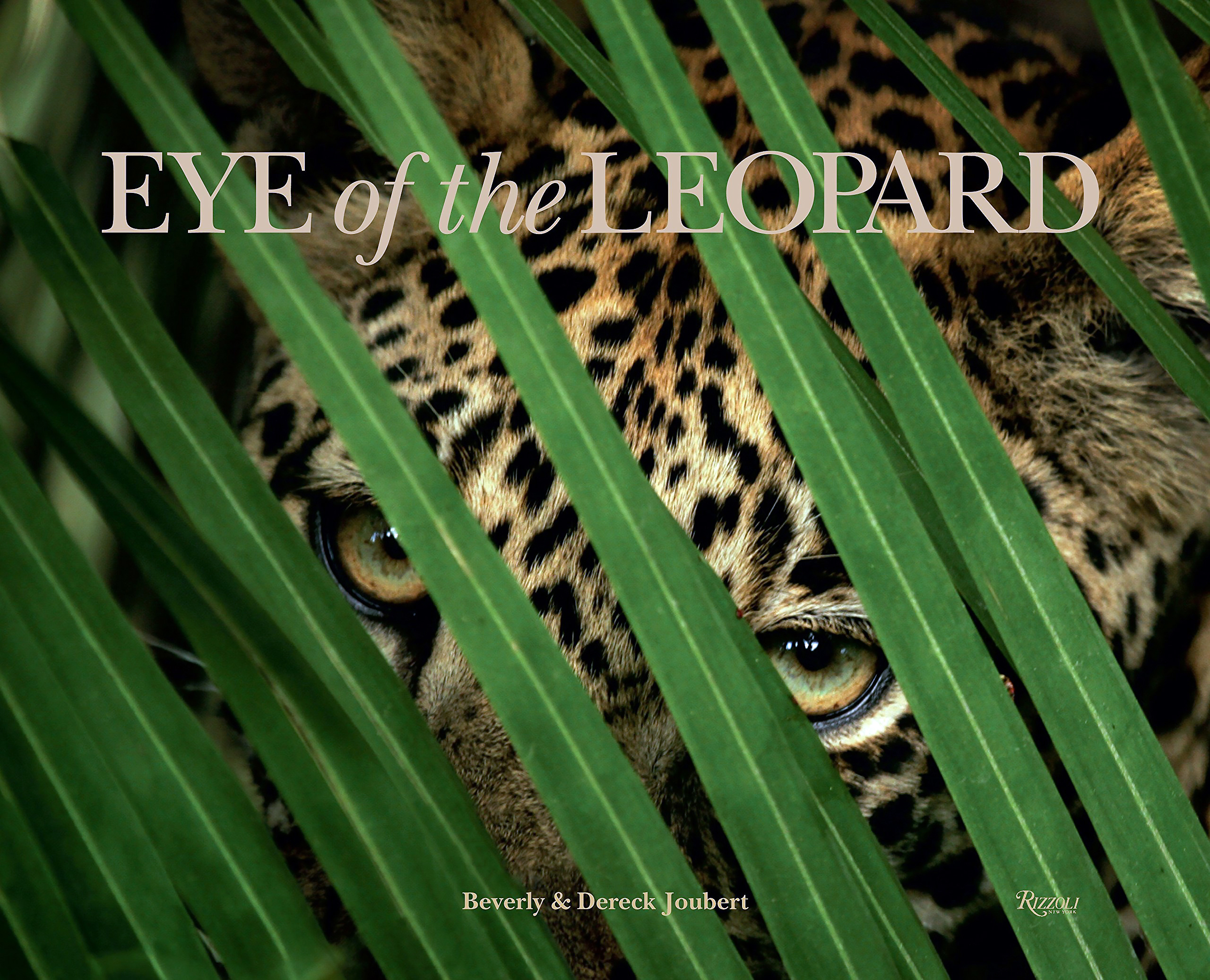

Their Emmy-winning 2006 film Eye of the Leopard follows the life of a single female leopard from infancy to maturity. In recent years, the Jouberts have focused more of their attention on efforts to preserve the endangered populations of lions, leopards, elephants and rhinoceroses. Their documentary Rhino Rescue recounts the struggle to save the endangered rhinoceros of Southern Africa. The Jouberts have organized a program, Rhinos Without Borders, to transport rhinos to safety from areas where they are at risk for poaching.

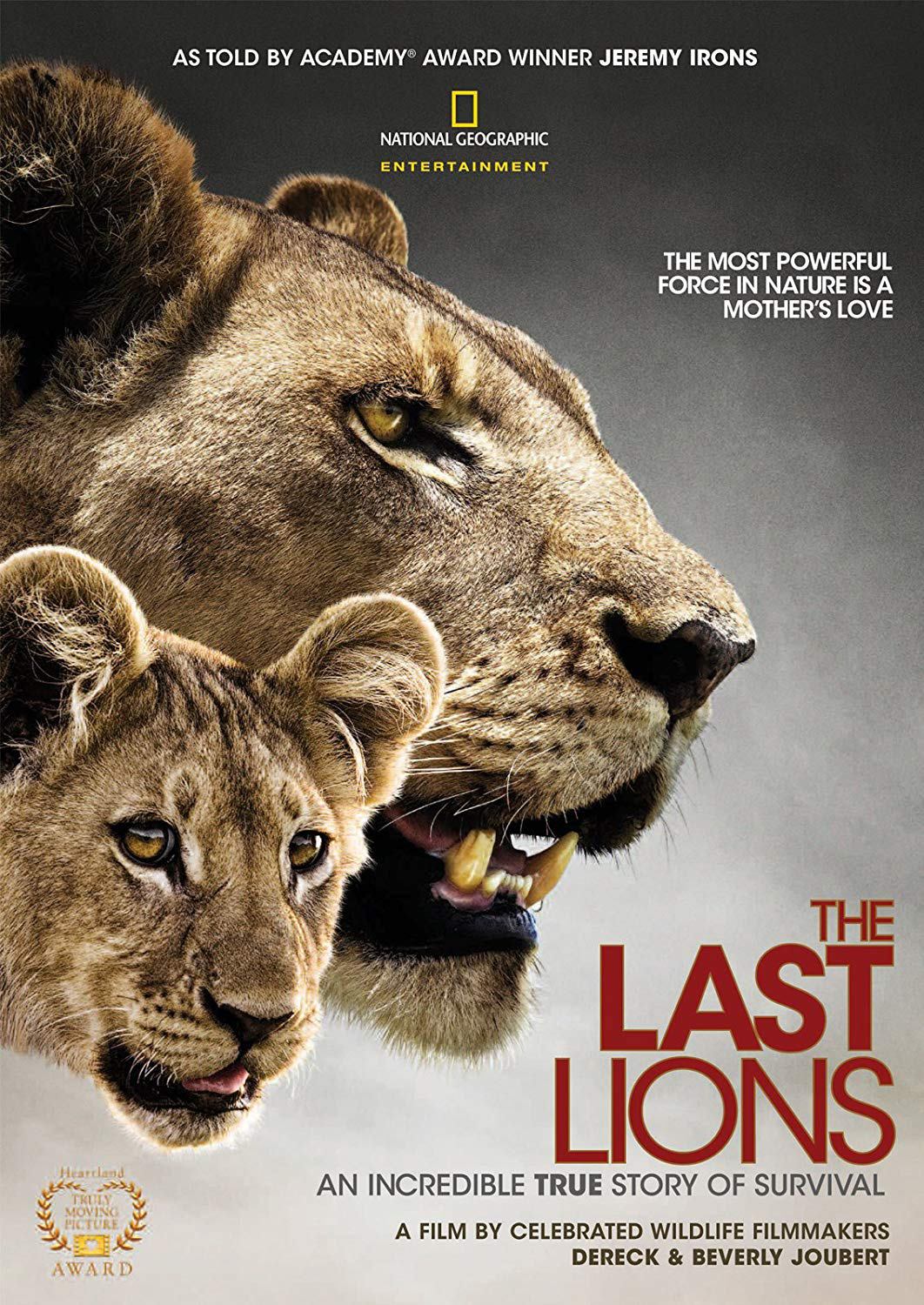

In 2009, the Jouberts partnered with National Geographic to found the Big Cats Initiative, “a long-term effort to halt the decline of big cats in the wild and protect the ecosystems they inhabit.” Their 2011 documentary, The Last Lions, filmed in Botswana, has helped alert the world to the danger that unrestricted hunting and habitat destruction pose to the “king of beasts.”

Living among lions, leopards, and hyenas, the Jouberts have faced danger many times, but nothing so terrifying as the incident they survived in 2017. While walking near their camp after dark, they were charged by an enraged buffalo. The animal, maddened with pain from a previous injury, knocked Dereck aside, breaking several of his ribs and cracking his pelvis. The buffalo struck Beverly with full force, driving one horn into her side, through her chest, and into her throat. The animal ran on with the half-conscious Beverly impaled on its horn. Despite his injuries, Dereck followed and managed to kick the beast hard enough to turn it around. The animal shook Beverly from its horns and struck Dereck again before running off.

The wounded couple spent the next 11 hours in the dark waiting for an airlift to the hospital while Dereck tried to stop Beverly’s bleeding by reaching inside her wound with his hand wrapped in gauze. Her heart stopped twice during the night and again in the plane the next day. She had lost five liters of blood, her lung had collapsed, her collarbone was broken, and her cheekbone cracked into 21 pieces. The buffalo’s horn had barely missed her carotid artery and stopped just short of her optic nerve.

Beverly’s injuries required 20 hours of surgery and 22 sutures, three months in the hospital and eight more of rehabilitation. On recovery, she was determined to return to the field to assist in the relocation of 100 rhinos from South Africa to safety in Botswana. Completely recovered, Beverly and Dereck are back in Botswana, in the land they love, recording the beauty of the country and its irreplaceable living treasures.

In January 2025, Dereck and Beverly Joubert returned to Botswana after six years away, marking a significant moment for their conservation work with Great Plains Conservation. Through the Foundation and its partners, they manage and protect more than 1.6 million acres across Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Kenya, focused on preserving iconic species such as elephants, lions, leopards, giraffes, and rhinos. In recent years, the Female Rangers program has grown, with women now conducting biodiversity patrols—one recent example covered 7,500 kilometers of wildlife monitoring by female and male rangers together. The “Solar Mamas” initiative, in collaboration with Barefoot College, has trained women from Botswana as solar engineers; these engineers have helped install solar panels in hundreds of rural homes as part of ongoing expansion. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Project Ranger delivered over US $1.5–2 million in emergency support to conservation staff and guides, while the broader team expanded from around 620 to over 800 people. With the opening of Sitatunga Private Island in the Okavango Delta, the Jouberts continue to unite conservation, local empowerment, and eco-tourism to help secure Africa’s wild landscapes for future generations.

In October 2025, Beverly Joubert released Wild Eye: A Life in Photographs, a magnificent large-format volume showcasing more than 250 of her most striking images taken across Kenya, Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Tanzania during four decades of exploration. Organized into five themes—Awe, Compassion, Humility, Intimacy, and Legacy—the book captures the spirit of Africa’s wildlife and landscapes through Beverly’s lens and includes Dereck Joubert’s reflections alongside each image. Together, they present a vivid portrait of the continent’s beauty and fragility, serving both as a celebration of the natural world and a powerful call to protect it for future generations.

Dereck and Beverly Joubert have spent the last 25 years living among nature’s most fearsome predators. From their camp in Botswana, hours from the nearest village, they record the social behavior and hunting practices of lions, cheetahs, and leopards, the most endangered — and dangerous — creatures on Earth.

The pair first met in high school in Johannesburg, South Africa, and fell in love with wildlife and each other while studying at the Lion Research Institute in Botswana. Dereck writes, directs and shoots their documentary films, while Beverly, an internationally acclaimed photographer, serves as producer and sound engineer. Together, they remain in the wild for months on end, editing their films in their tents. To date, they have produced over 25 documentary films, and written nearly a dozen books and numerous magazine articles, winning eight Emmy Awards and international environmental honors for their work. Their award-winning documentaries include Eye of the Leopard; Eternal Enemies and Soul of the Elephant.

Living among the animals they study, they have often found themselves in mortal danger. In 2017, Beverly survived horrific injuries when she was gored by a wild buffalo. Undeterred, the Jouberts continue their work, documenting and preserving the majestic creatures of the wild.

Let’s talk about the moment when you first set off. Do you remember the first time the two of you went out looking at the big cats that became the love of your life?

Beverly Joubert: Absolutely. I remember the first time going to Botswana. Dereck and I started working in the field in the early ’80s. We lived in the Eastern Transvaal — as it was then called — in South Africa. It was very close to the Kruger Park. And immersing ourselves in nature was thrilling, but it was in a very different way because we were at a safari lodge. And then…

Around about ‘80, ’81, Dereck and I went to Botswana on a holiday trip. Really, it was an exploration-adventure trip. And it was really canoeing in the Okavango Delta. And we immersed ourselves in the most incredible true wilderness, had no idea that what we had thought was true wilderness was totally different. And it was an exciting trip. We bathed in the Okavango — probably foolish at the time, with all the crocodiles — and really realized that we wanted to make Botswana our home. And it didn’t take long; it probably took about six months, and we were back in Botswana. We joined a lion research station. It was called the Chobe Lion Research. And that’s what we did for many years. The lion research was all researching lions, mainly at nighttime — observing them —because these lions were truly nocturnal, sort of 80 percent nocturnal, unlike many other places in Africa.

Dereck Joubert: So I think for us it really was about exploring, going out to that heart of Africa as we — as Beverly says, within that first trip into Botswana, and then realizing that what we had thought was wild was not that wild, and we needed to go wilder. We needed to go deeper into Africa. I think it speaks to both of our needs to understand the continent we were born on. Cape Town is part of that — so is Johannesburg — but it’s much more like the Riviera of Africa. We wanted to go further. We wanted to go beyond the Limpopo, beyond the Zambezi, and study where our DNA came from.

Can you tell us about the magic of Botswana and what it looks like, for those of us who will never get there?

Dereck Joubert: Botswana has many faces. But the part of it that we love most is in the Okavango, in the northern regions, where there are rolling plains at Kalahari sandveld, a huge variety of wildlife — big herds of elephants, probably one third to arguably half of the world’s elephants there. And for me, it’s the smell of the wild sage, and the elephant dung, and the mud, and the flood that just conjures up that wild place.

Beverly Joubert: And then putting us into our work there. We truly are discovering things that have never been seen before, especially the nocturnal work. We were working with 30 lions in a pride and a hyena clan of about 40 or 50, and they would come in and challenge the lions at nighttime. And we were watching battles that we had never, ever dreamt would happen. And in fact, I mean East Africa, when we spoke about it to the other scientists, they said, “It’s impossible. We see lions and hyenas lying together in the shade during the day. It could never happen.” And that’s really when we picked up cameras. We decided we had to document everything we were seeing so that it was really evident to all scientists through Africa.

What year was that?

Dereck Joubert: It was 1982.

Beverly Joubert: Right around 1982.

Dereck Joubert: We had sort of stepped into a war zone there. We didn’t expect it. We sort of fell in love with the beauty of this place. But two things were going on. One is the Savuti Channel — where we were kipped — was drying up. So when these rivers dry up, everything is in conflict around them. So we stepped right into that and then, almost immediately, into these epic battles between lions and hyenas that nobody in the world had seen before.

How close were you to these epic battles?

Beverly Joubert: Sometimes we wouldn’t push ourselves in, but they would come closer and closer to us. They got so used to us being out there nightly. We did that solidly for seven years, and I can tell you sleep deprivation is extreme. It really does make you go a little bit crazy. But we realized that what we were seeing was so unique and that nobody had ever seen it before, that we needed to keep going, we needed to document. But I think, at the same time — funny that you get so immersed in what you’re doing — that I think the daily adrenaline rushes that we were getting with the animals — I mean these battles were intense. We could pick up what the lions were feeling and then, of course, that aggression of the hyenas. And I think we started off — it was a great adventure, and intrigued — and then passion took over, immense passion, and we couldn’t stop. And even though we were totally exhausted a lot of the time, we just couldn’t stop. So the only way we could see it is this became an incredible obsession that we had to discover and unveil what was going on.

What about the danger?

Dereck Joubert: And working with these lions and hyenas, we got so attached to them, and they got so used to us, that in the lone moments when there wasn’t a battle going on, they would sleep underneath the vehicle. So we had these animals around us all the time. Very often, we found out that we could actually sleep in our vehicle — an open vehicle, no doors, no roof — with the lions sleeping underneath the vehicle and around us. And we were attuned to them getting up and moving and greeting. That would wake us up, and then we would all go on the hunt together. So we were embedded in a sort of war-correspondent way, embedded in the lion pride.

You did this for years, but just last year, a terrifying thing happened to you. Can you tell us about it?

Beverly Joubert: We were actually in our camp, and we were going from our tent to the main area. We both had torches; we were moving along a path that we’ve done for over 30 years. And out of the darkness, all that we heard — we had less than three seconds to react — was the snort of this very irate individual buffalo bull. And he came charging towards us. Dereck and I were walking together, and he just sort of came right to us. My instant response was to stay as quiet as possible and he will go away from us because we’re clearly not pinning him in at all. We’re not putting him in a corner.

And Dereck’s was — at that time, we saw that there was nothing to change the flight of this buffalo — Dereck put his hands up to sort of try and scare him away. But he hit Dereck on the side of his body. Dereck went flying— you know, the force of a one-ton creature. Dereck went flying and landed down the path. But at the time — and then the last thing I saw was this enraged eye, the white of his eyes — you could see he was angry and fearful at the same time. And he hit me straight in the face, and that was the last thing I remembered because he concussed me.

But I woke up on top of his horns, and I was impaled. At the time, I didn’t know I was impaled. And when I woke up, I remember instantly thinking, “This is interesting. I’m galloping with an animal.” And then it came all back that I’m probably on the buffalo, and I actually did give a silent plea of help within my mind. And then I said to myself — I was just so amazed that I was alive — and I said to myself three times, “I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive.”

So a 2,000-pound buffalo put his horn right through you. Did it go in one side and out the other?

Beverly Joubert: It didn’t come out. It went in under my armpit, through the chest, carried on, going through the throat. It lacerated inside the throat, and it ended up right here. It broke 21 bones in my cheek, my eye orbit collapsed, and then, of course, it shattered my collarbone, obviously, getting on that route.

Dereck Joubert: But then it came out the same way.

How did it come out?

Dereck Joubert: The buffalo hit me first, broke some ribs, cracked my pelvis, and then impaled Beverly. And as I looked up, I saw her being dragged off freely into the dark. And so I got up, and I chased after the two of them, shortened the distance, and calculated, I guess — or instinctively worked this out — landed on my left foot and kicked the buffalo with my right. And I kicked it in a spot where we later found out it actually had a wound, and that wound split open. So when that happened, he then tried to get to me, and he tossed his head and threw Beverly off. If that hadn’t have happened, Beverly would have been dragged off into the bush, and we would have heard hyenas later on. So then she crumpled down at my feet, and you remember, I put my finger under her nose to see if she was still alive, and she was.

Beverly Joubert: And I didn’t come round that I could speak to Dereck, but I was still unconscious. But I remember again, in my mind, I sort of said to myself, “My gosh, Dereck thinks I’m dead.”

Did you think she was going to die right there?

Dereck Joubert: As I was doing that, I heard the buffalo coming back. So again, we got a second chance at dying. So I jumped over Beverly, and I ran towards the buffalo and drew him where he sort of followed me at a 45-degree angle, knocked me down again, and then ran off. And then I went back, and I tested Beverly again and then realized that — and I often say, this is probably the hardest decision of my life, then, because you’re told in first aid that you shouldn’t move the patient. But I couldn’t imagine not moving Beverly, leaving her in the dark there, and going to camp for help. If she had woken up, it would have been traumatizing.

Beverly Joubert: Or the buffalo would have come back. Yeah.

Dereck Joubert: So I bent down, picked her up, cradled her head in my armpit, in the crook of my elbow, and then carried her for about 150 meters. And then the pain in my hip kicked in, and so then I fell down, and Beverly then woke up and said, “Don’t pick me up. I can walk.”

Did you think she was going to die right there?

Beverly Joubert: He fell, but it wasn’t hard on me at all. Maybe it was enough of a shock to get me to wake up.

Dereck Joubert: I put her onto her feet.

Beverly Joubert: But I remember sort of being on the ground, crumpled up, and looking at Dereck trying to pick me up, and I said to him, “I’m way too heavy for you to pick me up. I can walk.” And I kind of just unfolded my body, not knowing if there was anything broken or not.

Dereck Joubert: I wanted at that stage to say, “You could have told me that 150 meters back!”

Beverly Joubert: And of course, I started walking. Obviously, I was being supported by Dereck, and there was a lot of blood coming out. and I was bleeding and swallowing the blood down into my stomach from my face and from my nose. We walked probably about roughly the same distance Dereck had and then got to this wooden deck, and I stopped there. Dereck wanted to still get me into camp and get into a cooler area, and I said to him, “I can’t go any further.” So I just slid on the ground, and that’s where I stayed for 11 hours. That’s where Dereck had to cover me in ice to try and stop the bleeding and to get all the bandages and start looking at where the problems were.

Why 11 hours?

Beverly Joubert: Because it’s dark in the Okavango. They’ve got a policy that there’s no exterior lights. What I really am saying is it’s dark everywhere at nighttime. But they don’t want anybody flying at nighttime for security reasons, you know, for poaching, for many reasons.

Dereck Joubert: Safety reasons.

Beverly Joubert: And safety reasons.

Dereck Joubert: So we couldn’t get a helicopter in.

So you called, and they said, “Okay, we’ll come and get you in 11 hours.”

Beverly Joubert: No.

Dereck Joubert: They said, “We will catch you at dawn.”

Beverly Joubert: At dawn, yeah.

Dereck Joubert: We had communications with the president of Botswana, and he was going to come up in his helicopter to get us, but there was a cyclone in the town where the helicopter was, so he couldn’t get off the ground.

Beverly Joubert: There were many things. It was almost against all odds that I was going to survive because to have that experience and actually be impaled and pushed off the horn, a lot of the surgeons said it was remarkable. If they had put a surgical instrument into me and gone the same route and brought it out, they more than likely would have cut the carotid artery or the esophagus because that’s exactly where the horn had gone. So they were amazed at that part, that I survived. They were absolutely flabbergasted that I survived those 11 hours.

What did you do during those 11 hours?

Dereck Joubert: I was applying first aid. The biggest thing is I had to stop the bleeding. So I discovered, only after about 20 minutes, that this wasn’t just a scratch on the side of the face, which was the first thing, or a broken nose, but that the buffalo wound had gone in and left a wound on that side and underneath her arm.

Dereck Joubert: I tried to stop that bleeding. Ultimately, what I had to do was wrap a pad and bandage around my fist and insert it into her chest and change it every 20 minutes — but basically, left it there for about six hours to try and get that bleeding to stop. So five liters of blood she lost. And then at 2:32 she died, and I had to bring her back from that, and then at 4:40 she died again. But the journey through that was really much more an exercise in first aid, but also in keeping everybody calm. I think that when I had my hand inside Beverly’s chest, I realized that her lung had collapsed and that her collarbone was smashed. But even then, I had no idea how deep the horn had gone and that it had traveled up into her skull.

Beverly Joubert: Dereck has a wonderful way of saying, “No, don’t worry, it’s not going to be a problem.” But within myself, I was starting to feel certain sensations, and one was that I had this incredible crackling in my neck, and it was slowly blowing up, and that’s because the lung had collapsed. So the air had to go somewhere, and it was going into the cells and into the fascia of the muscle and all that, and that’s why I was getting that sensation. And then with the amount of blood that was pouring down the throat, I felt like my throat was burning like crazy. And Dereck said, “You know, it probably is the blood.” But what we discovered, only four days into the hospital — that he had lacerated and cut my throat, and so that was…

Dereck Joubert: The buffalo had, not me.

Beverly Joubert: Yeah, the buffalo, with the horn going in. So that was part of it. So I was feeling a lot of what Dereck was discovering on the ground. We were not talking about too much of it, although eventually, the pain in my shoulder was so extreme that I said to Dereck, “I think I’ve broken my collarbone.” And by that time he had also discovered that it was shattered in five places.

Dereck said you died twice that night — your heart stopped. Do you remember that? People talk about this feeling like they’re gone and then coming back. Did you feel that?

Beverly Joubert: I don’t recall anything that is this long tunnel or anything like that. Before that moment, I had got to a point where I realized that the amount of blood that I was losing — and obviously, my body was getting weaker — I said to Dereck, “Please don’t overdose me with painkillers.” And he said, “Why?” And I said, “I just want to be fully conscious. I want to be fully conscious because I think this might be the last time, and, who knows, when that time comes, I want to be able to say goodbye.” So that was incredibly emotional for both of us, and obviously, Dereck said, “I’m not letting you go. You’re not going to die.” I didn’t have the will to die, and I didn’t think that this was an easy way out. I really wanted to live. I really do feel that life is precious. But I knew that I wanted to leave my life in a very respectful way. I didn’t want to be shouting and screaming or anything like that. I wanted it to be a loving moment. So that was important to me. It might make it a little emotional now. But apparently, in the rescue plane, as well, there was a moment where all the — what do you call them?

Dereck Joubert: So we are flying down to — we’ve finally got help, at about seven in the morning, and then we started the journey back down to South Africa. And in that plane, Beverly crashed again and lost all vital signs. We had to give her a good shot of adrenaline into the heart, but she came back.