I never doubted that we were going to be free because, ultimately, I knew there was no way in which a lie could prevail over the truth, darkness over light, death over life.

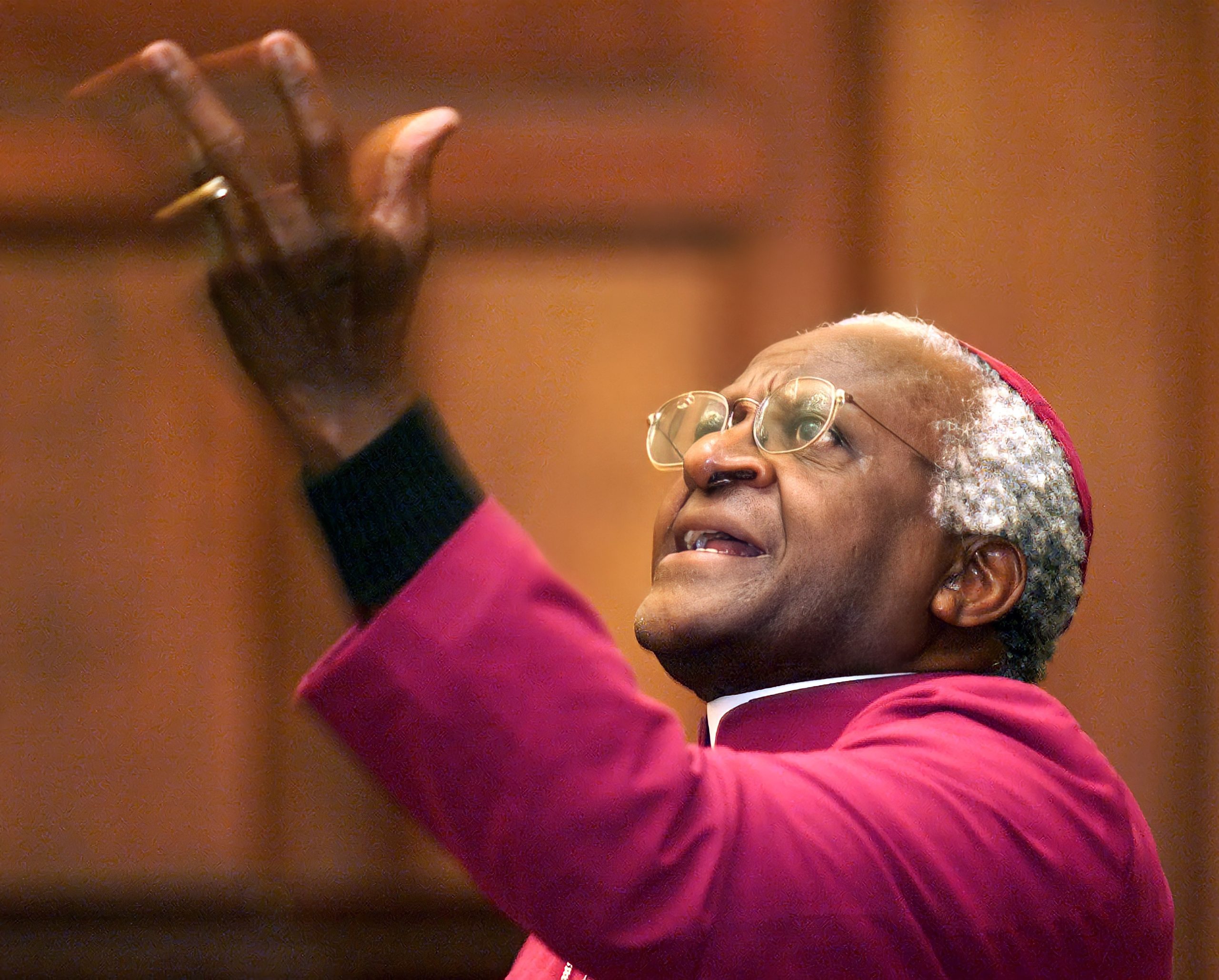

Desmond Tutu was born in Klerksdorp, in the South African state of Transvaal. The family moved to Johannesburg when he was 12, and he attended Johannesburg Bantu High School. Although he had planned to become a physician, his parents could not afford to send him to medical school. Tutu’s father was a teacher, he himself trained as a teacher at Pretoria Bantu Normal College, and graduated from the University of South Africa in 1954.

The government of South Africa did not extend the rights of citizenship to black South Africans. The National Party had risen to power on the promise of instituting a system of apartheid — complete separation of the races. All South Africans were legally assigned to an official racial group; each race was restricted to separate living areas and separate public facilities. Only white South Africans were permitted to vote in national elections. Black South Africans were only represented in the local governments of remote “tribal homelands.” Interracial marriage was forbidden, blacks were legally barred from certain jobs and prohibited from forming labor unions. Passports were required for travel within the country; critics of the system could be banned from speaking in public and subjected to house arrest.

When the government ordained a deliberately inferior system of education for black students, Desmond Tutu refused to cooperate. He could no longer work as a teacher, but he was determined to do something to improve the life of his disenfranchised people. On the advice of his bishop, he began to study for the Anglican priesthood. Tutu was ordained as a priest in the Anglican church in 1960. At the same time, the South African government began a program of forced relocation of black Africans and Asians from newly designated “white” areas. Millions were deported to the “homelands,” and only permitted to return as “guest workers.”

Desmond Tutu lived in England from 1962 to 1966, where he earned a master’s degree in theology. He taught theology in South Africa for the next five years and returned to England to serve as an assistant director of the World Council of Churches in London. In 1975 he became the first black African to serve as Dean of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Johannesburg. From 1976 to 1978 he was Bishop of Lesotho. In 1978 he became the first black General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches.

This position gave Bishop Tutu a national platform to denounce the apartheid system as “evil and unchristian.” Tutu called for equal rights for all South Africans and a system of common education. He demanded the repeal of the oppressive passport laws and an end to forced relocation. Tutu encouraged nonviolent resistance to the apartheid regime and advocated an economic boycott of the country. The government revoked his passport to prevent him from traveling and speaking abroad, but his case soon drew the attention of the world. In the face of an international public outcry, the government was forced to restore his passport.

In 1984, Desmond Tutu was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace, “not only as a gesture of support to him and to the South African Council of Churches of which he is leader, but also to all individuals and groups in South Africa who, with their concern for human dignity, fraternity and democracy, incite the admiration of the world.”

Two years later, Desmond Tutu was elected Archbishop of Cape Town. He was the first black African to serve in this position, which placed him at the head of the Anglican Church in South Africa, as the Archbishop of Canterbury is spiritual leader of the Church of England. International economic pressure and internal dissent forced the South African government to reform. In 1990, Nelson Mandela of the African National Congress was released after almost 27 years in prison. The following year the government began the repeal of racially discriminatory laws.

After the country’s first multi-racial elections in 1994, President Mandela appointed Archbishop Tutu to chair the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, investigating the human rights violations of the previous 34 years. As always, the Archbishop counseled forgiveness and cooperation, rather than revenge for past injustice.

In 1996 he retired as Archbishop of Cape Town and was named Archbishop Emeritus. For two years, he was Visiting Professor of Theology at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. Published collections of his speeches, sermons, and other writings include Crying in the Wilderness, Hope and Suffering, and The Rainbow People of God.

In 2007, Desmond Tutu joined former South African President Mandela, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, retired U.N Secretary General Kofi Annan, and former Irish President Mary Robinson to form The Elders, a private initiative mobilizing the experience of senior world leaders outside of the conventional diplomatic process. Tutu was named to chair the group. Carter and Tutu have traveled together to Darfur, Gaza, and Cyprus in an effort to resolve long-standing conflicts. Desmond Tutu’s historic accomplishments — and his continuing efforts to promote peace in the world — were formally recognized by the United States in 2009, when President Barack Obama named him to receive the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Watch a tribute to Nobel Peace Prize-winner Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s life and work. Listen to former South African President Nelson Mandela, other Nobel Peace Prize recipients, and inspiring achievers speak about the leadership of Archbishop Tutu in post-apartheid South Africa in the film Just Call Me Arch.

“We received death threats, yes, but you see, when you are in a struggle, there are going to have to be casualties, and why should you be exempt?”

When Desmond Tutu became General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches, he used his pulpit to decry the apartheid system of racial segregation. The South African government revoked his passport to prevent him from traveling, but Bishop Tutu refused to be silenced. International condemnation forced the government to rescind their decision. He had succeeded in drawing the world’s attention to the injustice of the apartheid system. In 1984, his contribution to the cause of racial equality in South Africa was recognized with the Nobel Peace Prize.

As Archbishop of Cape Town, spiritual leader of all Anglican Christians in South Africa, his spiritual authority dealt a death blow to white supremacy in South Africa. As chairman of the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission, he helped his country to bind up its wounds, and choose forgiveness over revenge. He continues to raise his voice for peace and justice all over the world.

Being the Archbishop of Cape Town carried political responsibilities. Had you seen the black African’s struggle to end apartheid escalating from one of peace to a more forceful resistance?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: I wasn’t really a political animal in the sense of being outraged almost all of the time but when I was at Theological College — I went to Theological College in 1958, and the year when I was going to be ordained a deacon is the year of Sharpeville, the Sharpeville Massacre when police opened fire on peaceful demonstrators against the past laws. Then, you know, you began — I mean, you intensified a sense of outrage that you had, which had developed actually even at Teacher Training College.

You see, in 1955 the ANC had this passive resistance campaign which didn’t succeed. In 1960 you had Sharpeville. You kept thinking that our white compatriots would hear — you know, would hear the pleas that were being made. I mean, we had people like Chief Albert Luthuli, who won the Nobel Peace Prize, the first South African to do so, who had been president of the ANC. And remarkably moderate really in the kind of demands that they were making, but it was — it kept falling on deaf ears, and increasingly people felt that it was going to be more and more difficult to bring about these changes peacefully.

I mean, even people like Nelson Mandela. I mean, they were striving to work for those changes nonviolently, and when they began engaging in acts of sabotage, they were very careful to ensure that they were attacking installations and not people. They tried to avoid casualties as much as possible. And it was 1960 that changed them when, after Sharpeville, and they were banned — the ANC and the PAC were banned — that they decided there was no real hope of a nonviolent end to apartheid. They were forced to take on the armed struggle, but even at that time I was not articulate, and there was an evolution.

I was appointed Dean of Johannesburg in 1975. And that — we were sufficiently political, my wife and I, because up to that point the Dean of Johannesburg had been white and the deanery was in town. My wife and I, we were in London. When we were appointed we said we’re not going to ask for permission, which we might have got, to go and live in town and the permission under — I mean, it wasn’t a right. We said, “Well, we’ll live in Soweto.” And so that — we begin always by making a political statement even without articulating it in words.

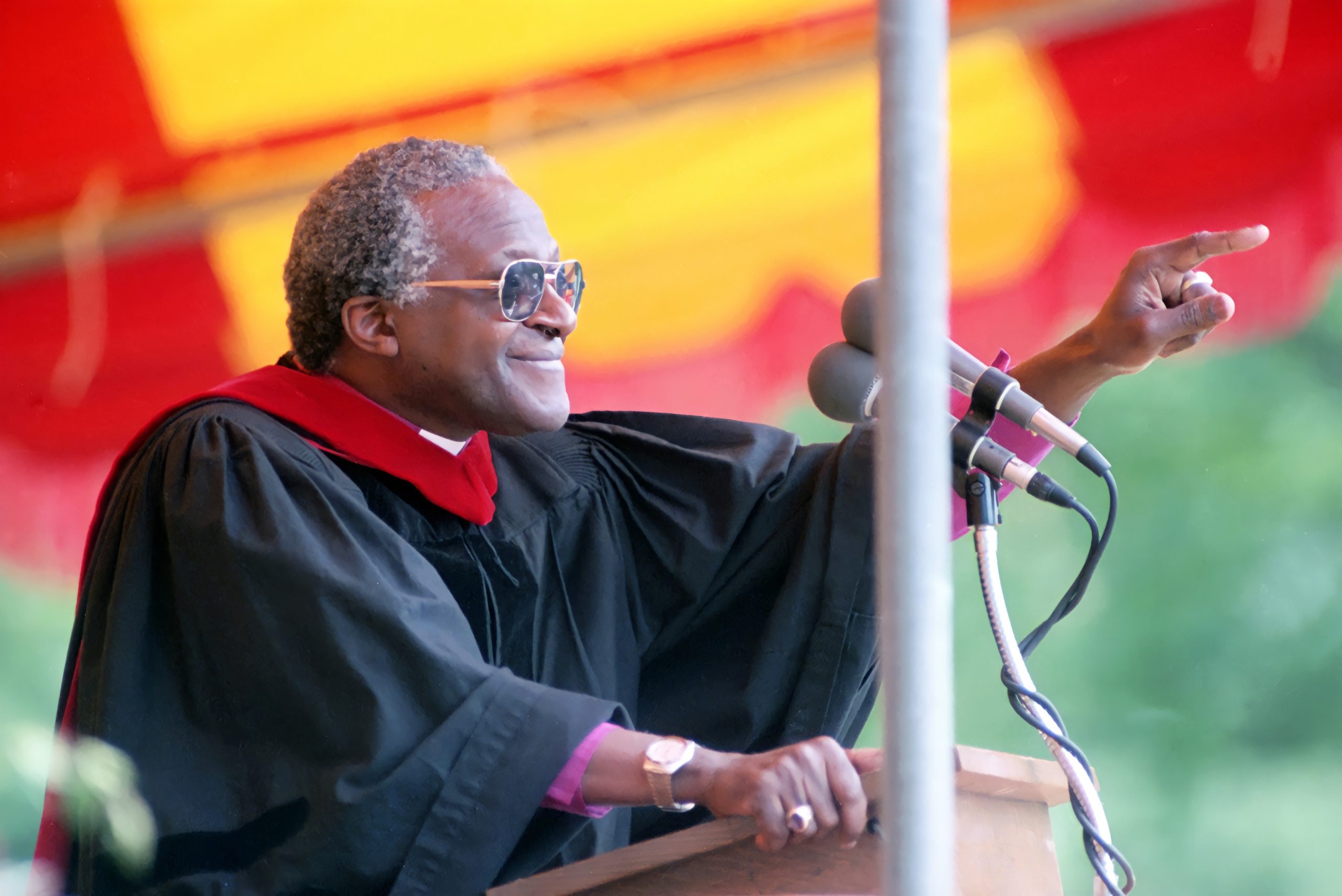

And when I arrived I realized that I had been given a platform that was not readily available to many blacks and most of our leaders were either now in chains or in exile. And I said, “Well, I’m going to use this to seek to try to articulate our aspirations and the anguishes of our people.” And I was — I mean for some reason the press were very friendly. I mean virtually anything I said it got fairly wide publicity, which was a great help.

But the thing I think that thrust me possibly into the public consciousness, I had just been elected Bishop of Lesotho. I had gone there to become bishop and I went for a retreat. I don’t know — I mean, I don’t know what happened but it just seemed like God was saying to me, “You’ve got to write a letter to the Prime Minister.” And the letter wrote itself.

In May of 1976 you wrote a letter to the Prime Minister warning of a building tension among black South African youth over the government-imposed Bantu education. What was its significance leading up to the June 16, 1976 riots?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: I wrote the letter to the Prime Minister and told him that I was scared. I was scared because the mood in the townships was frightening. If they didn’t do something to make our people believe that they cared about our concerns I feared that we were going to have an eruption.

I sent off the letter. I probably made a technical mistake by giving it to a journalist before hearing from the Prime Minister because this journalist was working for a Sunday newspaper and gave it enormous press, and I think quite rightly the Prime Minister was annoyed that I had not given him the opportunity but never mind. He, the Prime Minister, dismissed my letter contemptuously. I wrote to him in May of 1976. I said, “I have a nightmarish fear that there was going to be an explosion if they didn’t do anything.” Well, they didn’t do anything and a month later the Soweto [uprising] happened.

The South African government for some odd reason had ignored my letter where I warned. I didn’t have any sort of premonition, although I felt there was something in the air, but when it happened, when June the 16th happened, 1976, it caught most of us really by surprise. We hadn’t expected that our young people would have had the courage. See, Bantu education had hoped that it was going to turn them into docile creatures, kowtowing to the white person, and not being able to say “boo” to a goose kind of thing, you know, and it was an amazing event when these schoolkids came out and said they were refusing to be taught in the medium of Afrikaans. That was — that was really symbolic of all of the oppression. Afrikaans was the language they felt of the oppressor, and protesting against Afrikaans was really protesting against the whole system of injustice and oppression where black people’s dignity was rubbed in the dust and trodden underfoot carelessly, and South Africa never became the same — we knew it was not going ever to be the same again, and these young people were amazing. They really were amazing.

What was it about these kids that makes you use the word “amazing?”

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: I recall that on one or two occasions, I spoke to some of them and said, “You know, are you aware that if you continue to behave in this way, they will turn their dogs on you, they will whip you, they may detain you without trial, they will torture you in their jails, and they may even kill you?,” and it was almost like privata on the part of these kids because almost all of them said, “So what. It doesn’t matter if that happens to me, as long as it contributes to our struggle for freedom,” and I think 1994, when Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as the first democratically elected president, vindicated them. It was the vindication of those 1977 remarkable kids.

When you first began to speak out publicly against the apartheid system as Bishop of Lesotho, there must have been people who said, “This is hopeless. It’s not going to make a difference. There’s nothing you can do that will ever change anything.” How did you cope with that?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: Many of us had moments when we doubted that apartheid would be defeated, certainly not in our lifetime. But, I never had that sense. I knew in a way that was unshakable, because you see, when you look at something like Good Friday, and saw God dead on the cross, nothing could have been more hopeless than Good Friday. And then, Easter happens, and whammo! Death is done to death, and Jesus breaks the shackles of death and devastation, of darkness, of evil. And, from that moment on, you see, all of us are constrained to be prisoners of hope. If God could do this with that utterly devastating thing, the desolation of a Good Friday, of the cross, well, what could stop God then from bringing good out of this great evil of apartheid? So, I never doubted that ultimately we were going to be free because ultimately, I knew there was no way in which a lie could prevail over the truth, darkness over light, death over life.

And actually now having had the advantage of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and being able to look at some of the records of what the apartheid government was doing, the thing that is surprising to me is why so many of us survived. I mean, how is it that they did not assassinate more of us? And it is in a sense a mystery unless, of course, you say, well, God does have very strange ways of working because, I mean, they could have — you know, I mean, people say, “Well, maybe you were saved by the fact that you were in the church and you — ” and I believe that that is true.

I really would get mad with God. I would say, “I mean, how in the name of everything that is good can you allow this or that to happen?” But I didn’t doubt that ultimately good, right, justice would prevail. That I said — there were times, of course, when you had to almost sort of whistle in the dark when you wished you could say to God, “God, we know you are running the show but why don’t you make it slightly more obvious that you are doing so?”

And I mean, you know, you look and you say today there really isn’t a cause today in the world that captures the imagination, the support, the commitment of people in the way that the anti-apartheid cause did. I mean, the anti-apartheid cause was global. You could go almost anywhere in the world and you’d be sure to find an anti-apartheid group there. We are beneficiaries of an incredible amount of loving. People were ready to be arrested. They were demonstrating on our behalf. People kept vigils on our behalf. I mean you see it now in some ways — well, even before Nelson Mandela was released in 1988, Trevor Huddleston, who was my mentor and was President of the Anti-Apartheid Movement suggested that young people should come on a kind of a pilgrimage which would culminate in Hyde Park Corner on the day or very close to the day of Nelson’s birthday, the 16th, I think the 16th of July, and young people responded. Young people who most of them were not born when Nelson Mandela went to jail, in 1988, and they flocked. There must have been at least a quarter million young people congregated in Hyde Park Corner in London and Trevor Huddleston said — this was Nelson’s 70th birthday — “Let this be his last birthday in jail.” Now that was ’78 — in ’88. It’s not too bad when you think that two years later he was out. But, you know, here was a man who could command so much reverence and support especially from people — young people who had never seen him, heard him, seen pictures of him, were not born when he went to jail. That was a measure of the support that we have had.

What I have to say really bowled me over was how quickly the change happened when it happened.

One moment, Nelson Mandela is in jail, and the next moment, he is walking, a free man. One moment, we are shackled as the oppressed of apartheid; the next, we are voting for the very first time. I was 63 when I voted for the first time in my life in the country of my birth. Nelson Mandela was 76 years of age. But it happened, it happened. It happened partly because the international community supported us. People prayed for us. People demonstrated on our behalf, especially young people. Students at universities and college campuses used to sit out in the baking sunshine to force their institutions to divest and the miracle happened. We became free because we were helped and we want to say a big “thank you” to the world. And, you can become free nonviolently.

Did you and Nelson Mandela meet for the first time after he was released from imprisonment in 1990?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: I had seen him only once before, before he got arrested, in the 1950s when he adjudicated at a debating contest, and I was part of that. I never saw him really again, although now our houses in Soweto are not so very far apart. In 1990, I think it’s the 11th of February, he came out and came to spend his first night in the house which was the official residence of the Archbishop of Cape Town, and I was the Archbishop of Cape Town! He was ensconced with the leadership of his party, the African National Congress, and now and again, they would be interrupted. There is a phone call. This is the White House, and there is a phone call. This is the Statehouse in Lusaka. I mean, he was getting telephone calls congratulating him and wishing him well, and he then had his first — on the Monday, he had his first press conference as a free man on the lawns of Bishop’s Court. Sort of, that was the extent of our meeting. I mean, I met him in the morning just to say “hi,” but what I do remember is he went around thanking the people, my staff, for, you know, people who had cooked their meals. He’s always been gracious in that kind of way, but this is sort of the first time I saw his charm working on people.

There were times when you were subjected at the least to fierce criticism, and there were times when you must have feared for your life. How do you deal with that?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: We received death threats, yes, but you see when you are in a struggle, there are going to have to be casualties, and why should you be exempt? But I often said, “Look, here, God, if I’m doing your work, then you jolly well are going to have to look after me!” And God did God’s stuff. But it was — I mean people prayed. People prayed. You know, there’s a wonderful image in the Book of the Prophet Zechariah, where he speaks about Jerusalem not having conventional walls, and God says to this overpopulated Jerusalem, “I will be like a wall of fire ’round you.” Frequently in the struggle, we experienced a like wall of fire — people all over the world surrounding us with love. And you know that image of the Prophet Elijah — he is surrounded by enemies, and his servant is scared, and Elijah says to God, “Open his eyes so that he should see,” and God opens the eyes of the servant, and the servant looks, and he sees hosts and hosts and hosts of angels. And the prophet says to him, “You see? Those who are for us are many times more than those against us.”

When you first began, you knew what you were trying to do, and you perhaps had some idea of what you thought it would take to achieve this goal. Now that the goal of ending apartheid and creating democracy in South Africa is achieved, what do you know now that you didn’t know before?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: I have come to realize the extraordinary capacity for evil that all of us have because we have now heard the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and there have been revelations of horrendous atrocities that people have committed. Any and every one of us could have perpetrated those atrocities. The people who were perpetrators of the most gruesome things didn’t have horns, didn’t have tails. They were ordinary human beings like you and me. That’s the one thing. Devastating! But the other, more exhilarating than anything that I have ever experienced — and something I hadn’t expected — to discover that we have an extraordinary capacity for good. People who suffered untold misery, people who should have been riddled with bitterness, resentment and anger come to the Commission and exhibit an extraordinary magnanimity and nobility of spirit in their willingness to forgive, and to say, “Hah! Human beings actually are fundamentally good.” Human beings are fundamentally good. The aberration, in fact, is the evil one, for God created us ultimately for God, for goodness, for laughter, for joy, for compassion, for caring.