So after this long period of argumentation, and debate, I was better prepared to face critics who said, “Don, I think there really are two species in the collection, and you’ve made a mistake. I think the big ones are one species and the little ones are another species. What do you think about that?” I had already prepared my list of answers before that question even came up. We scientists, even though we think that we live in this ivory tower of truth, have to be prepared for the unanticipated. We have to be prepared to alter our views, to change or ideas, to make major changes in the way we view our own discipline. That was an extremely important learning experience for me. To this day, for example, I strongly believe that we have a pretty good idea of what the human family tree looks like. I think that many of my ideas are correct, but I’ll bet you, before my death other discoveries will be made that will prompt me to alter various ideas I have about human evolution.

So you not only have to take a lot of risks, but you really have to force yourself to be open-minded, and not be married to any one way of seeing things.

Donald Johanson: Absolutely.

I am very struck in reading about your achievements over the last 15 years or so, how early they came, relatively speaking, in your career. When did you first realize that you wanted to pursue anthropology? Did someone in particular help pique that interest?

Donald Johanson: In fact, there was one individual who became my mentor very early on. My father died when I was two years old, so I had no strong male image or personality in my life.

As a young boy, at about age eight, I met an anthropologist, who was out walking his dog. He was teaching at a theological seminary in Hartford, Connecticut. And, as I often jokingly say, his dog introduced me to him. And I became introduced because of that to anthropology. Something that probably most of us don’t even hear about until we are in college and take an introductory anthropology course, or whatever. But Paul Lazer, deceased now, was regularly going to Africa to pursue his area of work. He was a social-cultural anthropologist, in places like Tanzania, and Malawi, and so on. And I was thrilled as a young boy to sit with him, surrounded by his library of knowledge and to talk to him about his adventures in Africa. And I became very interested in Africa. I became very intrigued by the idea of going to a place as foreign and remote as Africa.

At the same time, I was particularly interested in biology. I had a huge butterfly collection. I went out and identified plants and insects, and so on. When the first fossils began to be found in eastern Africa, in the late 1950s, I thought, what a wonderful marriage this was, biology and anthropology. I was around 16 years old when I made this particular choice of academic pursuit. It was something I wanted to do more than anything else. I had a broad range of interests, biology and astronomy. But this was something that particularly intrigued me because of the personal contact I had with someone who I respected more than anyone else. What he was doing, to me, appeared to be extremely exciting. And I thought, wouldn’t it be marvelous if I could grow up to be an anthropologist. So my interest in evolution began in, of all places, a theological seminary.

Did you ever stop to wonder, if that dog hadn’t introduced you to the anthropologist, whether you would be doing something else today? Or do you think you would have found this field anyway?

Donald Johanson: I suspect that if I had not met Paul Lazer, if I had not had his remarkable influence, I would certainly have been doing something else. I think that, in fact, as I look back there was a very interesting thing which happened when I was a senior in high school. My first two years of high school, I was not a very good student. I was much more interested in what was going on outside of school. I was not stimulated to perform by the regular curriculum of high school. We didn’t have astronomy courses. We didn’t have courses in natural history, and there were so many other things I was interested in that schoolwork sort of got in the way and I did very poorly my first two years. After my sophomore year, Paul told me, “If you want to go to college, if you want to pursue an advanced degree, in whatever field it is you want, you need to get cracking in your school work.” I worked very hard the last two years of high school. In fact, I graduated something like 26 out of 300, did very well, but I did very poorly on examinations, Scholastic Aptitude Tests, for example. The reason I did so poorly was because I had read papers, which, of course, most students had not read, about the fact that these tests are highly biased. It really depends on one’s background. Taking a scholastic aptitude test that’s designed for a white Anglo-Saxon group of people and applying that to another group of people, these other people come out scoring very low, and the interpretation is that they’re not very bright. There’s a sense that they’re not terribly good, certainly weren’t at that time, very good ways to accurately reflect one’s intellectual capabilities, so I didn’t take them very seriously. As a result I did very poorly on them. There was a tremendous effort, or emphasis, placed on these examinations for entry to college. And when I went to the high school counselor, Mr. Olson, to discuss my college applications, he said, “Young man, I think you should apply to a trade school.” He said, “You’re not college material.” And Paul, at that point — I came back with this story. I was practically in tears, as you might imagine. Paul reiterated that these tests are not accurate tests of one’s capabilities and intelligence, and that I should apply. And I applied to several colleges and did get in. That sort of influence was terribly important to me because if I had not met him, and didn’t have that sort of influence in my life, I might have ended up going to trade school, becoming a plumber, or an electrician, or something else.

Were there particular books you read growing up that led you into this area?

Donald Johanson: I was particularly intrigued with astronomy. So I read a lot of books on astronomy. I read Lowell’s book on Mars, for example. I was very intrigued with the “canals” of Mars. But one of the books that played the largest role in my decision to become an anthropologist was a book written by Huxley in the late 1800s. Huxley was, as he is often called, Darwin’s bulldog. Charles Darwin formulated one of the most extraordinary ideas of the Western mind, the idea of evolution by means of natural selection. It’s interesting that today we have physicists trying to develop what they call the “grand unified theory,” something that would unify all aspects of the physical universe. We have spent billions of dollars sending telescopes into outer space, building radio telescopes, designing laboratory experiments to get down to things like the Z particle, and mu mesons, and all of these things that happen in cloud chambers, and so on.

Here was a guy, Charles Darwin, in the middle 1800’s who sat in a little home in Kent at Down and because of his five-year experience on the Beagle, traveling around the world as a naturalist, designed an idea of evolutionary change which is the grand unifying theory of biology. Today, even though biology is leaps and bounds beyond Darwin in 1859, when he published The Origin of Species, the basic core of biology is still natural selection. But, Darwin was a very retiring person. He didn’t want to go out and defend his theories when he was being attacked by, particularly by the church, but by other scientists. But, Huxley, one of his colleagues, really became the defender of his ideas. He wrote a book with a wonderful title, Man’s Place In Nature. Of course, the terrible thing that Darwin did was he removed humans from the center of the biological universe. He said that humans and human ancestors must have been susceptible to the same forces, the same whims and caprices of climatic change, evolutionary change, as any and all other living organisms. What Huxley tried to do in this book, was to really put man in his place in the natural world. I thought this was a brilliant idea. This was something that intrigued me, to realize that the same sort of plants and animals and insects that I was studying and was interested in — that we were there for the same reasons that they were. The same process of evolutionary change that brought about the Monarch butterfly, or the rabbits that I was observing in the neighborhood and so on, was the same process that brought us to where we are today.

Were you aware, when you were close to Paul Lazer as a young man, that there could be any kind of dichotomy or conflict between the seminary and the theory of evolution, the work that you were starting to do?

Donald Johanson: I was aware of it, but I grew up in a very a-religious family. My mother never went to church, she never had any religious training or background. It was never a part of our social interaction. I was aware of the conflict, but on the one hand, I felt that religion was pretty much based on an individual’s faith. I had colleagues in high school who were devout Catholics, who went to church regularly, who went to confession regularly, who really had religion play a large role in their lives. I felt that was their own personal belief. That was not something that I should necessarily tinker with or tamper with, or challenge. Because that was a personally held belief. But on the other hand, I thought that natural selection made so much sense, from the scientific viewpoint, that this was really something that one should evaluate in an entirely different realm, in the realm of science, which is very different from the realm of religion. So I was aware of it, but it did not cause me a great deal of conflict.

What was it about anthropology that attracted you so powerfully?

Donald Johanson: There is a tremendous amount of romanticism which surrounds going off on expeditions to remote parts of the world and camping in tents, and living in a desert and struggling with all of the trials and tribulations that one encounters. But, I think that what really intrigued me was the fact that I felt that this was and still is really, a science, a form of inquiry, which is still in its infancy. That there were so many things yet to be discovered, that the science itself would have, in my lifetime, still lots of surprises.

I was very strongly influenced by Paul not to go into anthropology. He said to me, “This is the age of science. Anthropology is sort of a 19th century study. The opportunities in biology, chemistry and physics are so enormous. We’re putting satellites in space. Computers are beginning to take over everything. You ought to go into something more practical than anthropology.”

I was a chemistry major for two years. But the whole time, I was still reading anthropology. I was going over to the anthropology department; I had taken some anthropology courses. It was still a love of mine, but I listened very closely to what Paul said: “You’d better do something that is going to pay off, something that is practical.”

Donald Johanson: One day I was sitting in — I believe it was organic chemistry class — and I realized that the 500 or so people who were in this lecture hall would all go home that night and solve the same problems and come up with the same answers. And those problems were the same problems that were answered by the class the last year and the year before. What I wanted to do was, I wanted to explore problems and areas where we didn’t have answers. In fact, where we didn’t even know the right questions to ask. Because often, the questions we ask, we found out were the wrong questions. We came up with new evidence that totally changed our whole view of what we thought about human evolution.

Paul and I started to have a long exchange of letters, back and forth, and I ultimately declared a major in anthropology. This was probably the only time I ever really disobeyed him. He died a few years ago, but before he died, I had the opportunity to make phenomenal discoveries in East Africa. I’ll never forget the afternoon when I arrived in Hartford, Connecticut and came to his apartment with the fossils I had found in Ethiopia, and unwrapped them. We sat on his living room floor and looked at them.

He must have been very proud.

Donald Johanson: Indeed he was. Yes.

You sound like you had the mind and the soul of a scientist almost from the beginning. Where did this come from? What kind of professions did your parents have? Were they in scientific fields?

Donald Johanson: No, not at all. My father, my real father died when I was two years old so I never knew him. He was a barber. He was a barber in Chicago. My mother had no formal education whatsoever. A very, very bright woman, very intelligent woman, but a woman when she was 16 years old living in Sweden, decided that the place where things were happening was the United States. It wasn’t in the old world as it was called. It wasn’t in Sweden. She wanted to be part of the new world. She borrowed money from her father. She didn’t speak any English. She left Sweden and came to the United States, landed in New York City and got a job in an ice cream parlor. Learned English, then went back and got the man she wanted to marry, who was my father. Once my father died, in 1945, my mother had a very difficult time financially. She spent her career being a domestic, being a cleaning lady. She earned enough money to support the two of us, and to assist me in my attempts to go to college. So there was a tremendous work ethic, which she had, and had a tremendous influence on me in terms of, if you want to do something, you can do it. There really are few obstacles that are going to prevent you from doing it. She was a very important role model for me, for very different reasons.

Still, anthropology didn’t sound like a terribly practical profession. Did she encourage you? Was she excited about this, or was she concerned about the practical aspects?

Donald Johanson: She was more supportive of my pursuing a career in chemistry. I had done very well in chemistry in high school; it was one of the things that really excited me. I was president of the Chemistry Club, and spent a lot of time in the lab doing all sorts of experiments. She could see a real practical application of this, so she encouraged me to do something in the more scientific realm. But when I changed to anthropology, she was supportive of that also. She never stood in the way. She encouraged me. I think she would have been happier had I done something more practical, but she was very supportive the whole way through. She just died this past year, at 88.

I’m sorry to hear that. She lived long enough to enjoy a lot of your triumphs. What were her reactions?

Donald Johanson: She was overwhelmed with the success I had, particularly success at such an early age. I had just finished my doctoral dissertation at the University of Chicago, that summer of 1974, and then went off to Ethiopia in September. In November of that year, I made a discovery which not only changed the course of anthropological theory and ideas, but changed my life’s direction enormously. This was tremendously gratifying to her, and she was very proud of what I had done. To see her son on the evening newscast with Walter Cronkite, or in the newspaper… She was extremely proud and gratified to know that I had made such a wonderful achievement.

You lost your father when you were still a toddler. What role do you think that loss played in your life?

Donald Johanson: Potentially, it could have been very damaging. I think it is important to have both a male and a female role model in one’s life. If I had not met Paul Lazer, I think my life would have been very different. I certainly would not have been as successful as I am now. When I was 13 years old, going through puberty, certain things would happen, and my mother would get very upset. Paul would come in and say, “Never hold a 13 year-old responsible for anything he did last week, because this week he is a different person.” He had a real understanding of the changes that we go through when we mature from a child to an adult. He played a very important role in my emotional development. And I think it is important to have both a male and a female role model in one’s life.

You were lucky in that. After you became an advanced student, was there anyone who gave you your first professional break?

Donald Johanson: Yes, there was. As an undergraduate, I had an opportunity to go on a number of archeological digs. So I had experience excavating, digging up remains of ancient Indian villages in the Midwest and in the Southwest. I was being channeled in that direction of North American archeology. But what really excited me was the idea that humans had a tremendous pre-history that went back millions of years. I wanted to go to Africa to find some of these creatures. I was at the University of Illinois, and there was no one there who was doing this kind of research, either in the field or in the laboratory. I was almost a year into my graduate work as an archeologist when I decided I really wanted an opportunity to work in Africa.

There was one man, Professor Clark Howell, who is now at the University of California at Berkeley, who was teaching at the University of Chicago. He is sort of the father of paleoanthropology, the study of human origins. He developed the whole multi-interdisciplinary approach to doing the sort of work we do in the field. He was at that time, working in southern Ethiopia at a site known as the Omo. I remember talking to my fellow graduate students about the fact that, “This is really what I want to do. I want to pursue human evolutionary studies, and I want to work with Clark Howell.” They said, “How are you going to do that?” I said well, “I have to meet the guy.” And they said, “How are you going to do that?” And I said, “I’m going to call him.” I called him at the University of Chicago. I called the anthropology department and was transferred to his office. He picked up the phone, and I told him who I was and that I was a student in Champaign-Urbana, and that I wanted to come to Chicago to meet him. He said that would be fine, and we set up an appointment. Here was sort of the Dean of American paleoanthropology who, you know, we had read about. Every student read his works. He was more influential really than any other individual in the United States and I had an appointment to see him. And I remember walking to his office the very first time – very cordial, very approachable man, and we sat down and talked. And then he said, finally he said, “What do you really want to do?” I said, “I’d like to go to Africa and find human ancestor fossils.” And he said, “Well, you know, a lot of people want to do that.”

He looked at me with a little grin, sort of telling me that this is not an easy thing. If we look at the number of people who are working in the field of human origins, in Africa, you can count them on one hand. The window of opportunity there is very small.

After this discussion, he invited me to come to the University of Chicago as an exchange student, for a half a year. I knew this was an opportunity that I had to seize, an opportunity that I had to devote myself to 110 percent. I worked very hard in the courses I took from him, and other professors, and after my first series of courses there, they asked me if I wanted to stay on as a permanent graduate student. There was a fellowship available that would support my work as a graduate student, so I left the University of Illinois and went to Chicago.

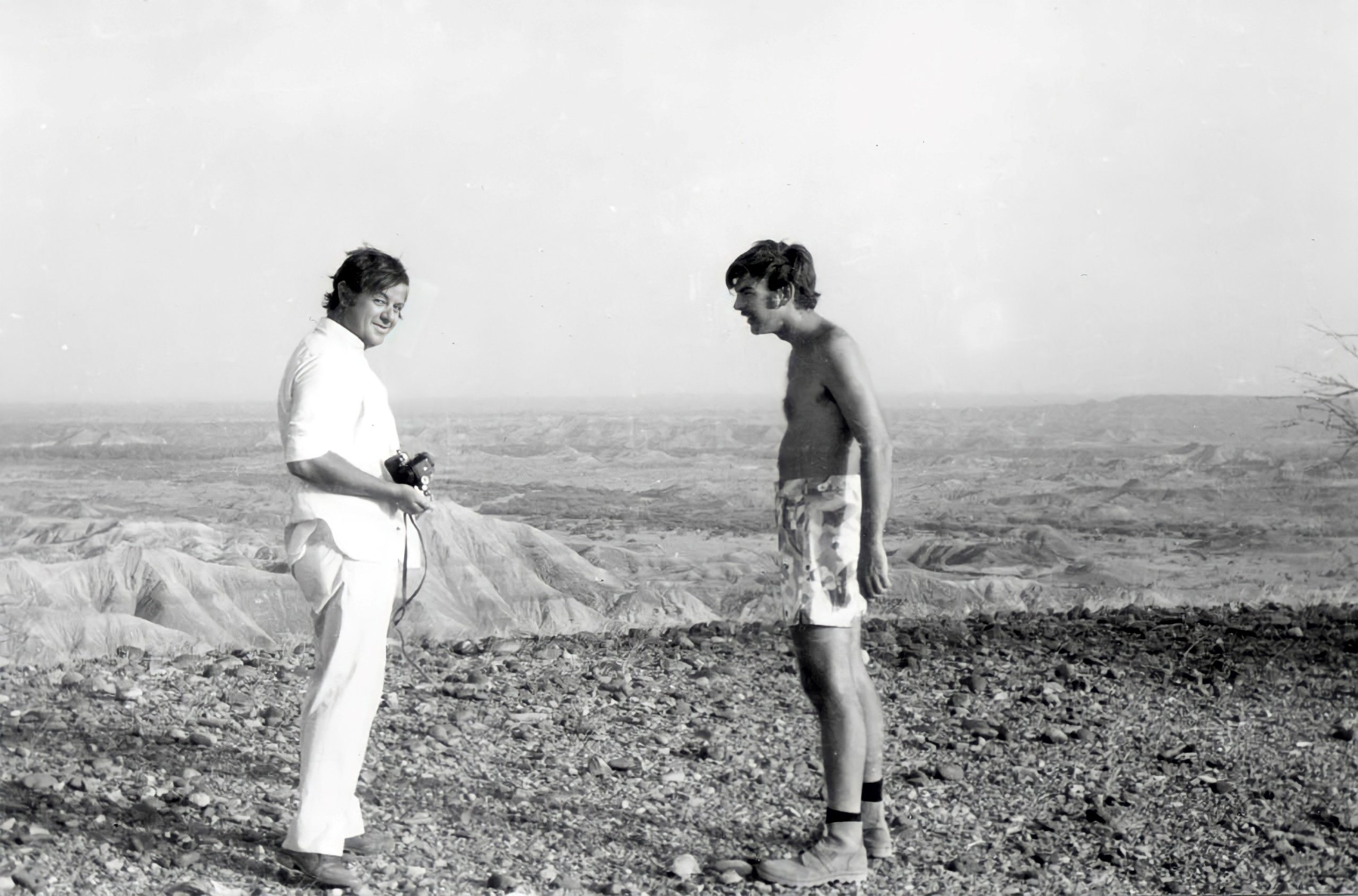

As a student, I was supported with a National Institutes of Dental Research Traineeship, so I was expected to do something in the area of teeth. And since teeth are the things that preserve the best in the fossil record, it was appropriate to do this sort of study. I did a long, very boring thesis on chimpanzee teeth. I traveled all over Europe and looked at museum collections, and published — or produced — a very thick thesis on all the detail of chimpanzee teeth. And that prepared me for understanding the teeth of our human ancestors better than anything else I could have done. During the course of my research for my Ph.D., Clark was working in Ethiopia, and he was going to study some fossils of human ancestors in South Africa. He was particularly interested in what he could learn from the anatomy of the teeth and he asked me if I had any ideas of things that he should look for. I spent several hours with him, and he said, “Why don’t you come with me on this trip?” Of course, I was thrilled to go to Africa to see the original fossils of this terrible tongue-twister, Australopithecus. And then I said, “Since I’m going to South Africa, and flying through Nairobi, why can’t I come up and visit your expedition?” He gave me that break. He said, “Why don’t you come up and visit us. Why don’t you come up and see what it’s like to be in the field, finding these fossils.” That was the break that all of us dreamed of as students. That was in 1970, and since then I have worked on and off throughout the Great Rift Valley of East Africa.

You sound like you were absolutely fearless at this young age. To just go to the phone and call up the most famous person in your field! How did you have the guts to do that?

Donald Johanson: I think a lot of this comes from what I saw in my mother. So often, personal tragedy cripples people to the point where they become emotional basket cases. They just can’t go on anymore. I saw a woman who, in spite of the most intense tragedy, had the strength to pull herself up and do something that wasn’t terribly flattering.

She had lived a very nice life with my father. He was extremely successful in his business, and they had a lovely home. The happiest moment in their life was my birth. From what my mother and her friends said, this was really the pinnacle in his life, to have a son. And he was so supportive, so helpful, so joyful, so full of love about this, that he just infected people with it. At the height of all of that happiness, this terrible tragedy happened. This man she lived with for most of her life died at a young age, in his early forties, when I was only two years old.

My mother was really left alone. The home had to be sold, the money that was saved in the bank had to be used, and she was faced with this problem: How did she support herself and me? She wasn’t trained, she wasn’t educated. One of the few things that she was able to do was go out and be a cleaning lady. But to her, this was not demeaning. She was still a proud person. This didn’t lower her status in her own eyes or the eyes of her friends. The people she worked for became very close to her and respected her tremendously. I still know some of these people. When they call or write a Christmas card, they always say how important an influence my mother was in their children’s growing up, because of the strength which she had.

Because of what she did, and how she faced difficult situations, she imparted to me a great strength, which is something that you don’t learn in the classroom. It’s not something that you learn from reading books. It’s not something you learn by getting a Ph.D. It’s something you need to learn in the real world. Any day, something could happen that would change your life and move you in a direction you never anticipated. You can grasp that, and flow with that opportunity, and say something good will come of this, as she undoubtedly did. If she had not done that, she would not have imparted to me the strength to go on.

When I was a student, and college became more and more expensive, I too had to get a job. I too had to work between midnight and four o’clock in the morning because we got 25 cents extra an hour by working the graveyard shift. So I worked for the physics department for two years and was able to finish my undergraduate work. And instead of complaining about that — instead of complaining about the fact that my roommates were all going out on Saturday night, they had say, a second-hand car, or they all went home for vacation when I stayed to make extra money so I could make it through the next semester — I faced it and embraced it as part of the learning experience. The learning experience of life. She imparted the strength which has carried me right through. That has helped me at every step in my career.

Do you think being an only child also had some effect on your fearlessness and ambition?

Donald Johanson: I think so. I spent a great deal of time by myself as a young boy, and had a very elaborate fantasy life. A very elaborate intellectual life, I guess you might say. Developed an interest in music as a young boy, listening to the radio, and so on. And I feel that being an only child, you have a lot of downtime when you aren’t interacting with your siblings. And instead of squandering that time, I used to dedicate that time to learning something more about music, something more about astronomy, something more about chemistry, or whatever.

I was very intellectually oriented, very early on. As an only child, I didn’t realize it at the time. I had dinner recently with some friends. One of them has four sisters, and she was telling stories about growing up with five in a family. I missed out on that. I don’t have siblings and, as I get older, I don’t have those people to fall back on, to share the common experience of how it was growing up. I have very few friends left who I knew in high school. So I am somewhat disappointed that I didn’t have siblings but, on the other hand, it gave me a lot of spare time to do other things.

Professor Clark must have seen that strength in you, to give a chance to this whippersnapper who calls him up out of the blue. He must have seen something in you that made him think, “Yes, this fellow can go far.” What do you think he saw?

Donald Johanson: It’s a difficult question for me to answer, but I think there is a clue. He was a farm boy who grew up in Kansas. I don’t know exactly why or how he got interested in human evolutionary science, but as an undergraduate, he wrote letters to some of the giants in the field. People like Franz Weidenreich, who is long dead. He was a German scholar who was most responsible for the Peking Man fossils. He had the courage and the strength as a student to write to someone like that. He carried on a long correspondence about evolution with one of the real giants. Think about a student today who is interested in astronomy, saying, “If only I could write to Carl Sagan. If only I could meet him and talk to him.” Well, you can. You can write to these people, and very often they will write back. I get wonderful letters from grammar school students, high school students who are doing a class project on Lucy, or doing class projects on human evolution. “Could you answer these three questions for my project?” Sometimes written in little ten year-old handwriting, or whatever. I always answer them. I think that Clark saw in me some of what he had in himself, the strength that he had to pursue what intellectually excited him.

When we’re kids, so often we are told by both our parents and our teachers, “Stay in your place. Don’t make waves. Do what you are told. Do what’s practical.” You seem to have broken all those rules, all along the way, and that’s how you were successful. Taking risks seems to be a very big part of being a successful scientist.

Donald Johanson: It certainly is. I’m trying to think of the first major risk I took. I guess it was when I was a senior in high school. It was a very conservative public high school. If you can believe, in the late 1950s, going to a public high school, where you had separate stairways for boys and girls. Separate cafeterias. Separate biology classes. It was like going to some sort of an academy. I was a very avid amateur astronomer, and we had a little astronomy club in high school. We had a remarkable telescope at the high school. It had been made in the late 1800s when the school was first built. We used this to observe all of the wonders of the sky.

I was talking to my physics teacher, whom I admired greatly, and he was despondent. The highway was coming through where the old high school was and there was no provision for an observatory in the plans for the new high school that was to be built. They were not going to move the telescope to the new school. I said, “They can’t do that! That’s impossible, they have to move the telescope. Who makes these decisions?” And he says, “They’ve done it. There is nothing that can be done about it. The Board of Education makes the decisions.” I found out that Board meetings were open to the public.

I corralled a couple of my fellow classmates and we went down to the Board of Education meetings and sat there. And when there was an opportunity to ask a question, this little 17 year-old kid got up and brought up the whole subject of the telescope. And they said, “Well, we are not moving it because it’s going to cost” — I forget what it was, $25,000 or something or other — “to build it, and that was not in the budget.” And I said, “Well, you can’t do that.” I said, “It’s too important.”

After that evening’s meeting, three or four of us got together, and I said, “Something can be done about this.” So we started writing to astronomy departments at Harvard and Yale and Princeton, and got letters of support. We delivered these letters to the Board of Education, and then we wrote a long letter to the editor of the Hartford Courant. This long letter appeared, and other letters came in supporting it, and before we knew it, the high school had to move the telescope. This was a risk, because of all the academic achievements I had made in the last two years. I was now part of the honors group and so on, even though there were people who thought I should go to trade school, because I did so poorly on my exams.

At this point the principal, Mr. Quirk, interesting name, came under a lot of pressure from the Board of Education to silence these students. And in fact, I was called in to the principal’s office and told that this was really not my role as a student, to interfere with what adults were doing and the decisions which they had made. And once the decision was made, there was a big article in the newspaper about how these young students had begun this movement and I all of a sudden became very unpopular with Mr. Quirk and others.

There was a really cold reception. I remember at graduation, when I did receive my prizes in a couple of different areas, they weren’t given to me as warmly as they were given to others. This was a risk I knew I was taking, because there was certainly a tremendous chance of failure, but I didn’t want to entertain the idea of failure. I said to myself, “We are going succeed at this”. If we succeeded, I knew that there would be a downside to it. And the downside was that I upset the apple cart. But I’ve always felt that risk-taking is an important part of what it means to be a human being.

As strong a confidence as you project, and as lucky as you were to meet Paul Lazer and so on, a lot of hard work has gone into the success you’ve had in this field. I wonder how you relate to the Edison quote about genius being one percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration.

Donald Johanson: I agree with him, essentially, 100 percent. One has to devote oneself to a particular pursuit. To be successful at anything, you have to make a total commitment to it. We so often see students who would love to play baseball like one of their heroes, or would love to be on the basketball court or the football field. They don’t see the 99 percent effort that went into practicing making baskets, or practicing hitting the baseball, or practicing catching a pass on the football field. It takes a tremendous amount of perspiration, a tremendous amount of hard work that you don’t always see or appreciate in the end result. You will find this over and over. Most achievers I know are people who have made a strong and deep dedication to pursuing a particular goal. That dedication took a tremendous amount of effort. That is certainly true in my case. It took a tremendous amount of work to get from point A to point B.

Despite all that hard work, I gather there was some resentment that success came to you relatively early. There may have been a sort of reverse ageism in your career. People may have made presumptions about you because you were young, and so successful. Do you think that’s true?

Donald Johanson: It’s partly true. There are some people in the field of anthropology who were stunned when these discoveries were made, and really stunned by the assertions which I made as a young scholar because I named a new species of human ancestor. I redrew the geometry of the family tree and overturned views of human origins which had been strongly held by individuals for, some of them, up to half a century. There was resentment that this young upstart came along, stumbled across this skeleton in the desert and now makes these tremendous assertions. And I think now, after more than a decade of debate and controversy, most of my ideas, many of my ideas, are accepted by a great majority of anthropologists. But there has been a long period of debate, a long period of controversy. And there certainly has been a certain degree of jealously, where people are stunned. “How could this person have made these discoveries? Why wasn’t it me? Why didn’t it happen to me?” And that has generated, unfortunately, a certain degree of jealousy.

Even when you’re in the upper echelons of academia and science, you are still dealing with petty jealousies. I guess you really have to form a thick skin, don’t you?

Donald Johanson: You do. There are always going to be people who are envious of what you have done. All you can do is hope that by showing them what you are doing, and why you are doing it, and inviting them in to be a part of it, that they will change their minds, and they will see that there is an important role to be played by everyone who is interested in this particular subject, whatever subject it might be.

Do you want to talk a little bit about the Leakeys?

Donald Johanson: Unfortunately this is one of the friendships which has dissolved over the last 15 years. It’s very unfortunate for our personal relationship, and it’s very unfortunate for the field, because we have seen different camps develop. You know, “Are you in the Leakey camp, or are you in the Johanson camp, or are you in somebody else’s camp?” I have always encouraged people within my research group to have their own ideas. There are people here at the Institute of Human Origins who disagree with various aspects of the way I interpret fossils. But I think that is extremely healthy for science. It’s unfortunate that the dissolution of our friendship has resulted in the establishment of different camps.

I take it that your inner strength, which you got from your mother, saw you through that period. It still must have been painful for you to experience this backbiting and these doubts.

Donald Johanson: It has been. There have been some friendships lost over this. That’s the most difficult for me. I find it very uncomfortable to know that I was at one time close friends with someone, and because of jealousies and misunderstandings and so on, these friendships have dissolved.

I feel personally hurt when someone says things about our research that are not true. For example, one of the important responsibilities that every scientist has is to share their research with everyone, and to share their ideas through publication and so on. But also to share their objects — the things they work with — with other scientists.

In our case, finding a Lucy is unique. No one will ever find another Lucy. You can’t order one from a biological supply house. It’s a unique discovery, a unique specimen. Everyone who is studying human evolution, particularly the early stages of human evolution, wants to look at her, wants to measure her with their calipers, and observe her anatomy, and make their interpretations on the fossils. The skeleton itself was on loan to us in the United States for five years, and scientists came on a very regular basis to come and make their own observations. I allowed everyone and anyone who wanted to come, to study the original specimens, because eventually they would be returned to Ethiopia, where they are now, housed at the National Museum.

It really hurts when you submit a grant proposal to the National Science Foundations and one of the reviews comes back, accusing you of refusing them access to the fossil. Of course these are anonymous reviews, so you don’t who wrote them. Somebody is very jealous of your accomplishments and says, “I don’t want him to get this National Science Foundation grant, so I will say that he is hiding information and refusing access.” In fact, this happened when I submitted a large proposal for the scientific evaluation of our discoveries. I had to invite the director of the National Science Foundation out to Cleveland, where I was based at that time, to show him our guest book, with two hundred signatures of people who had come to the lab. “Thanks for the opportunity to study the original fossils,” and so on.

That really does hurt, when someone uses an opportunity like that to try to damage your professional career. Because it’s not only damaging to yourself, it’s damaging to the whole team. The success which we have had in understanding human origins, finding fossils like Lucy and interpreting those fossils, has really been a coordinated multi-interdisciplinary effort. And it’s because we’ve had a team of scientists working together. The rest of the team gets tainted with this. People say, “Are you working with the guy who is accused of hiding fossils from other scientists?” Things like that are difficult to live with. You have to try the best you can — without reacting in the way that your gut tells you to react — to sit back, take a deep breath, and say, “This is not true. How do we turn it around, and make it productive?”

You obviously went through a barrage of criticism and professional jealousy. Looking back at that difficult, turbulent time, do you think any of that criticism was justified?

Donald Johanson: It depends. I was a very forceful young scientist. I really felt that these discoveries were of tremendous significance, would have a profound meaning for changing our whole view of human origins. I was very forceful at scientific meetings. I was sometimes very brash. I wouldn’t shout down other people, but I would certainly make an argument in a way that was so forceful that some people refused to argue with me. They didn’t want to get involved in it. I think that in some instances I was a little too aggressive. A little too right. If I had to go back, I’d probably soften some of my presentation. People criticized me, and said, “He’s really a brash young guy, who is presenting his ideas as if they are the ultimate truth.” If I could go back to do that, I would have presented them in a different way.

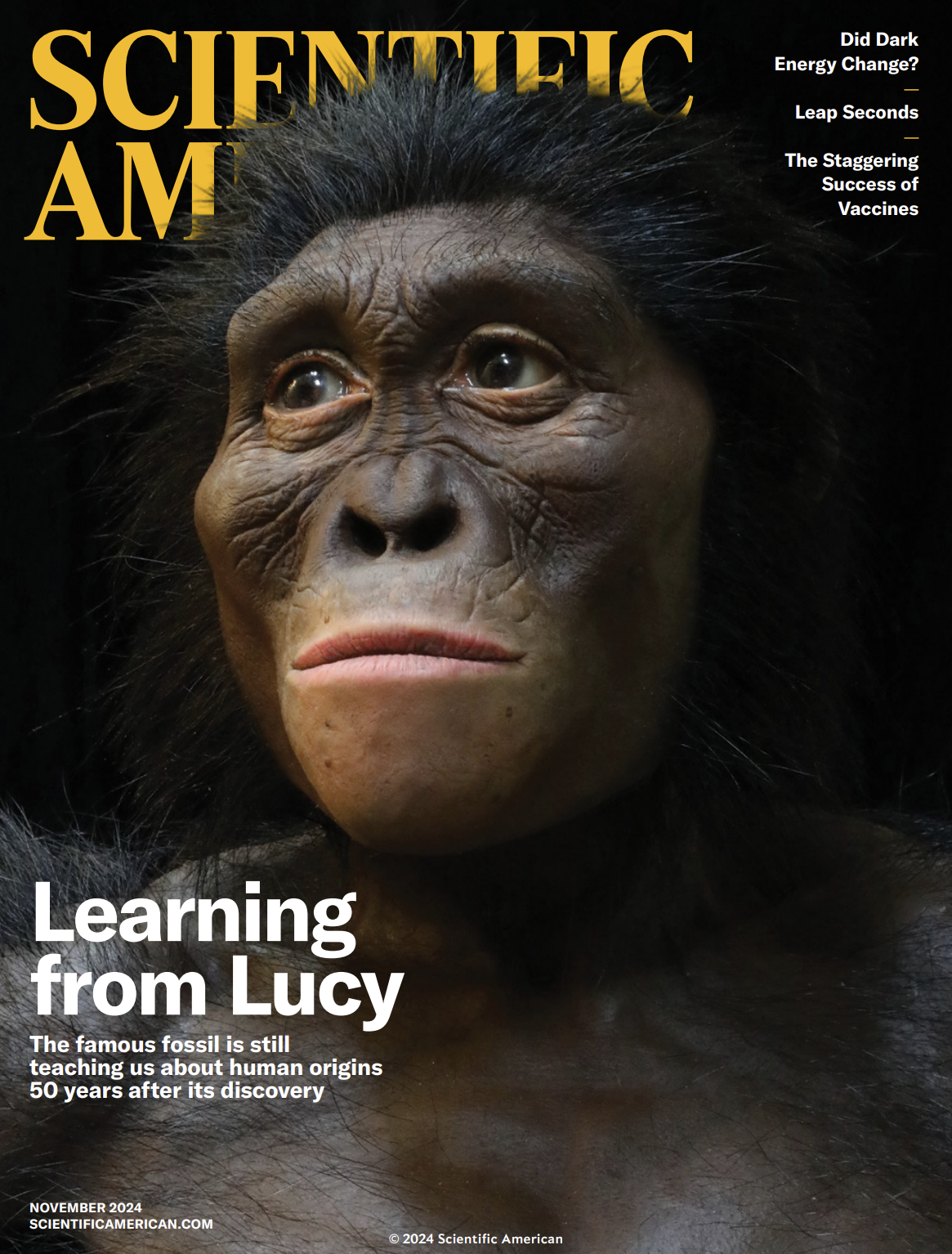

Why do you suppose Lucy captured the public’s imagination? It’s getting clearer and clearer why she captured anthropologists’ attention, but what about this unique set of bones is so compelling?

Donald Johanson: I think that all of us, at some stage in our lives, asked that question, ‘Where did we come from?” We’re satisfied with different answers at different stages of our lives. When we begin to look at our own personal lives and begin to trace our own ancestry back, we are lucky if we can go a few generations. But people are really intrigued with knowing something about the earliest origins of the human family. Knowing something about the conditions, the situation, what our ancestors looked like millions of years ago. There is a real thirst and desire amongst people to know something about origins. Origins of all sorts of things, but most importantly, origins of themselves. Lucy brought with her an image of our human ancestors that you don’t get when you find a jaw or an arm bone or a leg bone. Here was 40 percent of a single skeleton. I suspect also popularizing her by giving her an affectionate name like Lucy was important because people can identify with that. If I meet someone on an airplane for example, and we get into a conversation talking about, “What do you do for a living?” and so on, and I say, “I’m an anthropologist.” “What kind of anthropology do you do?” and I say, “Well, I look for fossil in East Africa, human ancestor fossils. And they say, “Oh, did you ever find anything?” When you say, “I found a fossil called Lucy,” they immediately know. If you said, “I found a skull of Australopithecus afarensis,” it really wouldn’t be as attractive. But once you personalize it with a name, people identify with it immediately. So I think she is very visible because of her name and because of her completeness. She gives us a better picture of what these creatures looked like than anything that had ever been found before.

In a sense, we’ve all found a mom.

Donald Johanson: Well, when we think of our origins, we often think of “the mother of mankind.” The “Eve hypothesis” of the emergence of modern humans has been talked about recently. There is a comfort that people have in identifying with a female image. That may be part of it.

Was it difficult for you to deal with sudden fame? What were the challenges of that?

Donald Johanson: The thing that I found most difficult to contend with was the fact that my life became very public. There was a piece in People magazine. There was a piece in the Style section of the Sunday newspaper. There were people taking pictures of me in my living room, asking me about my lifestyle. There were people following me in my laboratory. There were people who came to the field, and made movies. And I felt, “Gosh, I really would like to be left alone to pursue my own work. I’m really uncomfortable with this. I have to get up in front of an audience, and give a public lecture, something that I was not prepared for as a graduate student. I have to get on camera, and talk to people who are watching on television.” I was on the Today show, and Good Morning America, and so on. Yet, as it was happening, there was something in the back of my mind that found this attractive. I had to learn certain sorts of things, but it turned out that I was pretty good as a communicator, to bridge this big gap between the scientists and the non-scientist. I was involved in a scientific pursuit that did captivate people’s interests. People were interested in their origins. They weren’t going to sit down and read the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, and plow through all of that terminology on teeth and jaws and bones. But they wanted to know something about the importance of those discoveries for themselves. I realized that I could bring to these people the results of our scientific inquiries in a way that they could understand.

I was on Good Morning America, or one of those shows, with Diane Sawyer, and after the show I received a letter from Carl Sagan. He said, “You must have converted hundreds of young people to become anthropologists.” That was a wonderful thing for Carl to do. I met him subsequently. And we’ve talked about this. His peers, astronomers who have criticized him for popularizing science, too, have criticized him. Carl and I, and other popularizers of science, don’t think that science should be a secret. Science should be available to anyone and everyone who wants to study it, or understand it. It’s our responsibility to make it understandable to them in a way that they can grasp. While I was, at the beginning, caught between these two horns of the dilemma — one being a scientist, one being a popularizer — I realized there was tremendous value in making this material available to people who really were excited about knowing more about where they came from, and how they got here.

How has Lucy changed our perceptions about the evolution of the family tree?

Donald Johanson: The major impact which Lucy has had is on a previous scenario of human origin where people felt that there were a number of events, evolutionary changes, which all went together. That our ancestors stood up to free their hands so that they could make and use stone tools. In order to make and use stone tools, they had to have large brains. This has view has been pretty much a view that’s dominated human origin study, ever since it was suggested by Darwin in the middle 1800s. Here comes Lucy, about 3.5 million years old. She has a very small brain, not much bigger than that of a chimpanzee, and we have never found any stone tool, stone artifacts, associated with her species. Yet she is walking upright. So it appears that upright, bipedal posture and gait, walking on two legs, precedes by perhaps as much as a million and a half years, the manufacture of stone tools and the expansion of the brain. That means that there has to be a major new way of looking at what it was that sparked humans to separate from our closest relatives, the chimpanzees. What that precipitated was a whole series of changes in the way people understood the relationships between different species of human ancestors.

For example, the Leakeys have held for over half a century now that there are two parallel lines of evolution. That there is one line of true man, or Homo, the larger-brain form that goes back millions and millions of years, independent of these smaller brain forms. But Lucy draws those two lines together, into a common ancestor, between three and four million years. Now, over a decade since we made that initial announcement of a new species and a new geometry to the family tree, virtually everyone who deals with reconstructing the relationships between the different kinds of fossil ancestors, places Lucy at the trunk of the tree. So she really is the mother of all mankind. She is a mother to all the various branches, some which went extinct, and one which ultimately evolved into ourselves.

So she had a very major impact on how we understand the relationships between the different species, as well as a very major impact on our understanding of the sequence of events that led from an ape-like creature to a more human-like creature.

Why did the brain develop, if not for the reason that we all thought for so long?

Donald Johanson: We’re getting into an area of what questions are remaining in terms of human evolution and there are so many. One of the most important ones is “Why did the brain expand?” If it wasn’t associated with stone tool manufacture, if it wasn’t to make better stone tools, why did it expand? What were the selective forces in an evolutionary perspective that selected for individuals with larger brains? There is a suggestion by primatologists, people who are studying primate societies that intelligence is a very important element of social behavior and social interaction. Those creatures that live in more complex societies, like the primates for example, monkeys, and particularly apes like chimps and gorillas, are fairly intelligent. Not because they are making and using tools, but because they live in a society where there is a complex set of relationships. There is a web of interconnectedness between individuals in a society that demands a high level of intelligence. There is a suggestion that the social milieu in which our ancestors evolved was a fairly complex one. This is one of the interpretations which has been suggested for why our ancestors became upright. They became upright because of increasing complexity in their social and physical world. There developed a whole series of relationships that were centered around the human family, in fact. Lucy may represent the first step in the evolution of the human family. The human family is a very important aspect of our adaptation. And what helps solidify that is intelligence. So that, while Lucy didn’t have a brain much bigger than that of a chimpanzee, it probably was wired somewhat differently, and was probably relatively more intelligent than that of a chimpanzee. And that was because of the sort of social life that she lived.

You seem to be implying that human psychology has been terribly important, even 3.5 million years ago.

Donald Johanson: Well, what we have found, subsequent to Lucy, at the site of Hadar, was a remarkable collection of over two hundred bone specimens at one fossil site. Of adults, males and females, big ones and small ones, individuals as young as two years old. A child’s skull of about four years old. Which suggests that even back then, our ancestors had to have been living in groups. Look at the size of Lucy. She was only three and one-half feet tall at the most. Very short individual, very small in size. She would not have been able to live out on the savannas by herself, without the support of a larger group. So I think there is some evidence in the fossil record also, that our ancestors were living in groups and not living as individuals or just as a pair, for example.

Has that way of looking at things also provoked controversy in your field?

Donald Johanson: There is very little we say in our field that doesn’t provoke controversy. I gave a lecture a number of years ago at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and it was entitled “Human Origins: 3.5 Million Years of Controversy.” Because every time something new is announced in the field of anthropology, it goes through a period of controversy and conflict. Much of what I published in the late 1970s precipitated tremendous controversy. There were groups who felt that there were two different kinds of hominids at the time of Lucy, rather than one, as we suggested. That has generated enormous literature. There are some people who believe that Afarensis, the species to which Lucy belongs, was not yet fully terrestrial, and bipedal, that there are certain aspects of her anatomy, like the fairly long arms, that suggested that they were still climbing in the trees. Others say “No, absolutely not. They were wholly out of the trees. They were fully committed to terrestrial bipedal locomotion.” There are two major groups which have developed. Some of those individuals don’t even talk to one another, except in the scientific literature. So she has precipitated tremendous controversy about her origins.

You discovered Lucy in 1974. It is now 1991. What are the challenges ahead for you? What are you dying to get your hands on next?

Donald Johanson: There are two major areas which interest me the most. One of them is between two and three millions years. This is a period of time for which we have very few fossils. We have a few specimens from East Africa. We have some from South Africa. People often talk about the missing link. Every time you find one of these fossils, it’s another link in the chain, because the chain of evolution is a long and continuous one, so each one could be called the missing link. The link between Lucy and the ones which we think are our direct ancestors is still missing. Homo habilis, or the handyman, as he is called, was making stone tools two million years ago, and had brains twice the size of Lucy’s. It’s very provocative to think that Lucy existed, as a species, unchanged for a million years. What stimulated that species to change? What were the climatic, environmental pressures on that species to change, and for that change to generate a tool-using, culture-bound animal. We depend totally on culture for our survival. Without culture, we wouldn’t make it. Picture yourself totally stripped of your clothes, out on the grasslands of East Africa. How would you even survive a week, without something as simple as Swiss army knife? What was it that provoked that change from a non-tool making, small-brained form, to a larger brain, stone tool-making form. And that’s a mystery. That’s still one of the most exciting periods in the human career that is as yet unsolved.

The other one is what preceded Lucy? We can go back pretty well to about four million years. At four million years, we have bits of jaws, bits of skulls, bits of leg bones, which are virtually identical to those of Lucy. So her species went back to about four million years. Beyond that, once we dig deeper into the fossil records, we have a few molars, a little scrap of jaw, but nothing that tells us what caused the apes to go in one direction, and the humans to go in another. We know from genetic studies that humans and modern African apes are so closely related to one another, that they share 99 percent identity in their DNA. If you were to take that strand of DNA out of you or me, and stretch it out, and put next to it the DNA of the chimpanzee, there would be one percent difference. Yet look at the enormous differences there are between chimps and us. That means we must be evolutionarily closely related to the apes. That means the separation between the apes and the humans probably happened as recently as five or six million years ago. Not like people have wanted, Say 15 to 20 years ago, people believed that separation was 20 million years ago. We were comfortably separated from these “beasts.” Now we find out that they are very closely related to us. They are cousins in the true sense of the word cousins. They are remarkably close to us. The work that Jane Goodall and others have done on chimps in the wild shows that there are many behaviors which chimps have that forecast what we think of as human.

This leads to a consideration of things like, “If they are that closely related to us, how can we keep them in tiny little cages for experiments? They must have some of the same emotions which we have.” Lucy has been important in all of this, because she has sometimes been called the ape that stood up. Here was a creature which still has in her anatomy certain evolutionary baggage which is left over from her four-legged, quadrupedal ancestors. But yet, she made that crucial step towards what it means to be human.

I find it ironic, walking in the Institute of Human Origins, that this is connected to a Christian organization. Obviously, what you have spent your life studying is in direct contradiction to some religious view of human origins. Do you have any interaction with religious groups?

Donald Johanson: We are housed here, in Berkeley, in space which we rent from a church’s divinity school, which is an Episcopalian seminary. There really is very little interaction between their staff and our staff. We are really dealing with two different views of understanding our origins. One, as I said, is based on faith. It’s really based on what you believe in. That’s something that science should never invade. In other words, we should never take a person’s faith and subject it to scientific inquiry. You never set up a hypothesis which says: Jesus was the Son of God, true or false. There isn’t a true or false about it. You either believe it or you don’t. And you don’t take the scientific evidence and subject it to religious questions. We don’t ask the question, is gravity moral? Gravity is a fact, it’s a law. Everyone can accept that. I think that while there are, of course, conflicts and differences between the two, they deal with totally different philosophies and perspectives on how we understand the physical world around us. There are many people I know, and I’m sure you do, who are religious, who do believe in a divine creator, someone who has designed all of this, and that one aspect of that design was evolution. There is no conflict in their mind. Evolution can be accepted as a scientific fact and part of the whole glory of creation.

Were you born an anthropologist, or do you think you could have been as successful a chemist as you are an anthropologist?

Donald Johanson: It’s an extraordinarily difficult question. I believe I have been successful in my own scientific arena, partly because of the passion which I brought to it and the dedication I brought to it. But on the other hand, being in the right place at the right time, with the right preparation, is also important. In 1971, when I was working in Ethiopia, I met a French geologist. He was looking for an anthropologist to work with him in the northern part of Ethiopia, in an area which is very rich in fossil sites. So I was in the right place, I was there at the right time, and I had the right preparation. I seized that opportunity. I have no idea whether or not the right place and the right time would have been there had I been a chemist. The passion, the drive, the ability, the sensitivity, the hope, the wish, the desire, all of those things that are important would have certainly been a part of me. So I think you can make a prediction based on that, and say, yes, I would have been successful. Whether I would have been as successful as a chemist as I am as an anthropologist, is difficult to say.

What advice would you give a student who wanted to become an anthropologist? What are the most important things to be aware of and to follow?

Donald Johanson: For the last six years I’ve had a professorship at Stanford University. Unfortunately, because of other requirements on my time, I have had to resign this professorship. I was often asked by students who wanted to be anthropologists, “What do I have to do?” In the field of human origins studies, I’ve strongly emphasized a very substantial background in biology, in the earth sciences, particularly geology. These are the tools which one needs to interpret the evidence. There will always be very little opportunity for people to actually go to the field and find fossils. We have lots of fossils in our vaults at the moment which still need interpretation, evaluation, analysis. In the field of human origins, there are too many folks who don’t have a strong enough background, particularly in biology. Lucy, and these other creatures we spoke about, were subjected to the same forces of natural selection and evolutionary change as all the other animals and plants living at that time. The interpretation of these fossils will be based on a better understanding of biology and evolutionary change. I have suggested very strongly to these students that they develop a strong background in zoology, biology, genetics, evolution, and so on. Because there really are very few opportunities to go to the field and actually find fossils.

What personal characteristics do you think are most important for success in any career?

Donald Johanson: One of the most important things is to choose something which is emotionally, philosophically satisfying to you, and gratifying to you. I’ve taught, off and on, for the last ten years. So many of the students I have spoken with after class, have talked about how they want to go out and make a lot of money. They want to have a big car, they want to have a wonderful house, they want to control a lot of money. Yet they don’t bring a passion to any particular subject. If you can bring your own passion, your own excitement, your own emotional commitment to something, you will be successful. And success should not be measured in a materialistic way. Because success which is measured in a materialistic way does not have the depth of success that you reach when you really do something you are committed to. I was very fortunate in being successful in an area I gave commitment to very early on. You may choose a particular profession that will produce a lot of material wealth, but the bottom line is that you enjoy doing what you are doing.

You talk about the need for a geology background in your field. Why are the fossils so rich in that particular area of Africa?

Donald Johanson: The area of Africa where I worked since the early 1970s is known as the Great Rift Valley. The Great Rift Valley of East Africa has been developing because the horn of Africa has been slowly moving away from the bulk of Africa because of continental drift. As it has been doing so, it’s been thinning the earth’s crust and allowing volcanoes to emerge. It has had areas of subsidence, where you have had lakes and rivers. This has been an ideal environment for animals to die, fall into these lakes and rivers, and be slowly transformed into fossils. The same processes of earth movements which were going on to create this environment are still going on, and promoting a great deal of erosion. The same processes that brought about their preservation are bringing about their re-exposure on the surface. It’s an ideal environment in which to find these fossils.

What was it like for Lucy? Do you have a picture of what the earth looked like when she walked upon it?

Donald Johanson: We do. We have done extensive studies to reconstruct the paleo-environment where she and her species lived in Ethiopia. We know that it was dominated by a very large lake, fed by rivers coming off of an escarpment, where there were heavy rains. There was a diversity of environments. There were deltaic environments around the delta of the river, there were environments along the lake margin, there were riverine forests, open grasslands, woodlands, and so on. We can reconstruct much of that environment because we have remains of the fossilized animals that lived alongside of her, the antelopes and gazelles that lived in more open areas, certain kinds of monkeys that lived in more closed areas. We even have the fossil pollen grains of these various plants. So we can say something about the specific kinds of trees and grass and so on that were available. We know what kind of a world she actually lived in.

What would you do, other than anthropology, if you had a next life? Are there other fields that seduce you?

Donald Johanson: I have two major interests. One of them is photography. I do a lot of still photography. I bring my cameras along on these expeditions and make some nice pictures. Whenever I’m out on a photographic safari in East Africa, it’s always one of the great moments of tremendous happiness, to be out there at dawn, watch these animals, photograph them, and come back and look at these fantastic pictures. Photography is an area which I have pursued as a hobby, and have also been able to use in my own profession.

The other area I have been very interested in is music, particularly opera. I’ve jokingly said if I ever do come back, I’d like to come back as an Italian tenor who is also a photographer. Many of us in science are dedicated to our work almost 24 hours a day. I think about my work all the time. As I’m driving home, or sitting at dinner with my wife, or going out with friends, I’m talking about my work, talking about recent discoveries, recent ideas about the fossils. It’s very important for us to take a deep breath and move away from that. Get involved in something else that is really separate from this world that captivates you all the time. Then you return to your work refreshed. In the United States, there is this terrible urge to become workaholics, to work seven days a week, to not take vacation. “Oh, I haven’t taken a vacation in five years.” When someone says that to me, that’s not a positive remark. It’s a negative remark. Last summer, I was in Europe for three weeks with my wife, and I came back totally refreshed, ready to embrace all sorts of new ideas and problems in my own science.

I’m sure. Do you have any athletics that you pursue, any sports?

Donald Johanson: At the moment, tennis. My wife and I play tennis several days a week. She’s a better tennis player than I am, but we have a great time. I hate to keep relating it back to Lucy, and the fossils, but think about it. We’ve been here five million years. Most of that existence was spent in a very physically active world. People think human beings are the pinnacle of evolution. We have to buy videotapes, and watch some person exercising to encourage us to exercise. We have to pay money to go to an exercise club and work out during the day, when, this was part of our natural world for millions and millions of years. It is important to get out there and do something physically strenuous. It’s a way of cleansing you of all the emotional baggage that is brought about through culture, for example. Physical activity is very important for our whole functioning, our mental clarity. So I think exercise and sports are very important.

We do seem to have come a long way from Lucy. We live very different lives today. I gather from some of your writings that you are deeply concerned about man’s increasing distance from nature, and from our animal roots.

Donald Johanson: I am. I don’t like to take the doomsday perspective, and say, unless we do this for the environment, or this for the world, we are all going to go extinct. I think we still have the ability to make a major impact on the globe, to put something back into the environment other than pollution. We can do something to make the world a better place not only for ourselves, but for all creatures to live in. But I think part of what has happened is that we have become very dramatically separated from the world, which created us. The world of natural selection, the natural world in which Lucy and these other fossils lived is a world we lived in for millions and millions of years. Because of the development of culture, and our dependency on culture for survival, we have been removed from that environment very dramatically. I have a sense that, in our genes, we’re still programmed for living on the savannas of East Africa. Those millions of years of evolution are still part of our genetic make up. Yet culturally, we have moved so for beyond that, that there is an imbalance between our natural background, and our artificial world of culture. I think this imbalance is something you need to recognize, to overcome the problems that are associated with it.

I don’t believe we are innately destructive animals. When we recognize certain behaviors in human societies which are destructive for the natural world, we can do something about them. We have the most intelligent brain we know of. We can use that brain to do wonderful things for this planet. It is my hope that, by understanding our ancestors, understanding where we came from, we will ourselves leave descendants who will sometimes look back and ponder their ancestors.

You talked about our self-deception, the fact that we humans think ourselves superior to other animals. That’s another idea that I think is thrown out of kilter by your research.

Donald Johanson: Evolution, for me, is no longer a theory. It’s virtually a law. I think that evolutionary change which was brought about by means of natural selection is, in fact just like gravity, a law. No matter what organism we look at on this planet, we can explain its existence and its origins through this process of natural selection. What this does, what this constantly does for me and what it does I think for many people who read some of the things I’ve written is be reminded of the fact that it was the natural world that was important for our origins. And we ought to be kind to that natural world, and do what we can to preserve it. Not only for ourselves, but also for all those other creatures in the natural world.

With that comes the fact that we also are vulnerable. There is nothing in the history of this earth, for three and a half billion years that life has been on the earth,that guarantees in any way whatsoever, that we, unlike all of the other species which have gone extinct, will not go extinct. If one looks at the evolutionary record in a broader perspective, the majority of animals, organisms that have lived on this planet are extinct. There are very few that have survived, and those that survived will also go extinct. We have to think about the fact that even though the dinosaurs ruled the earth for tens, hundreds of millions of years, they too went extinct. That it is a way to remind us of our vulnerability.

In photographs of your digs, you are accompanied often by a guide carrying a gun. Why the gun?

Donald Johanson: The area of Ethiopia where we work is occupied by nomadic tribesmen, Afars, who wander from place to place. They have had a long-standing conflict with another tribe, and both sides carry weapons. There often are skirmishes between the groups, so one has to have some protection when we are out there.

So actually, anthropology can be quite dangerous.

Donald Johanson: It can be, but in the field where we work, we have made friends with a number of these Afar tribes. Some of them we have worked with for over 13 years, and they have become close friends to us. I don’t think we’d be able to work there if we didn’t have their trust and understanding. It’s a very special environment for us to work in.

Well, you are a lucky man, and you’ve given us a lot. It’s been great talking to you. Thanks a lot.

Thank you.