What could be worse than getting to the end of your life and realizing you hadn't lived it.

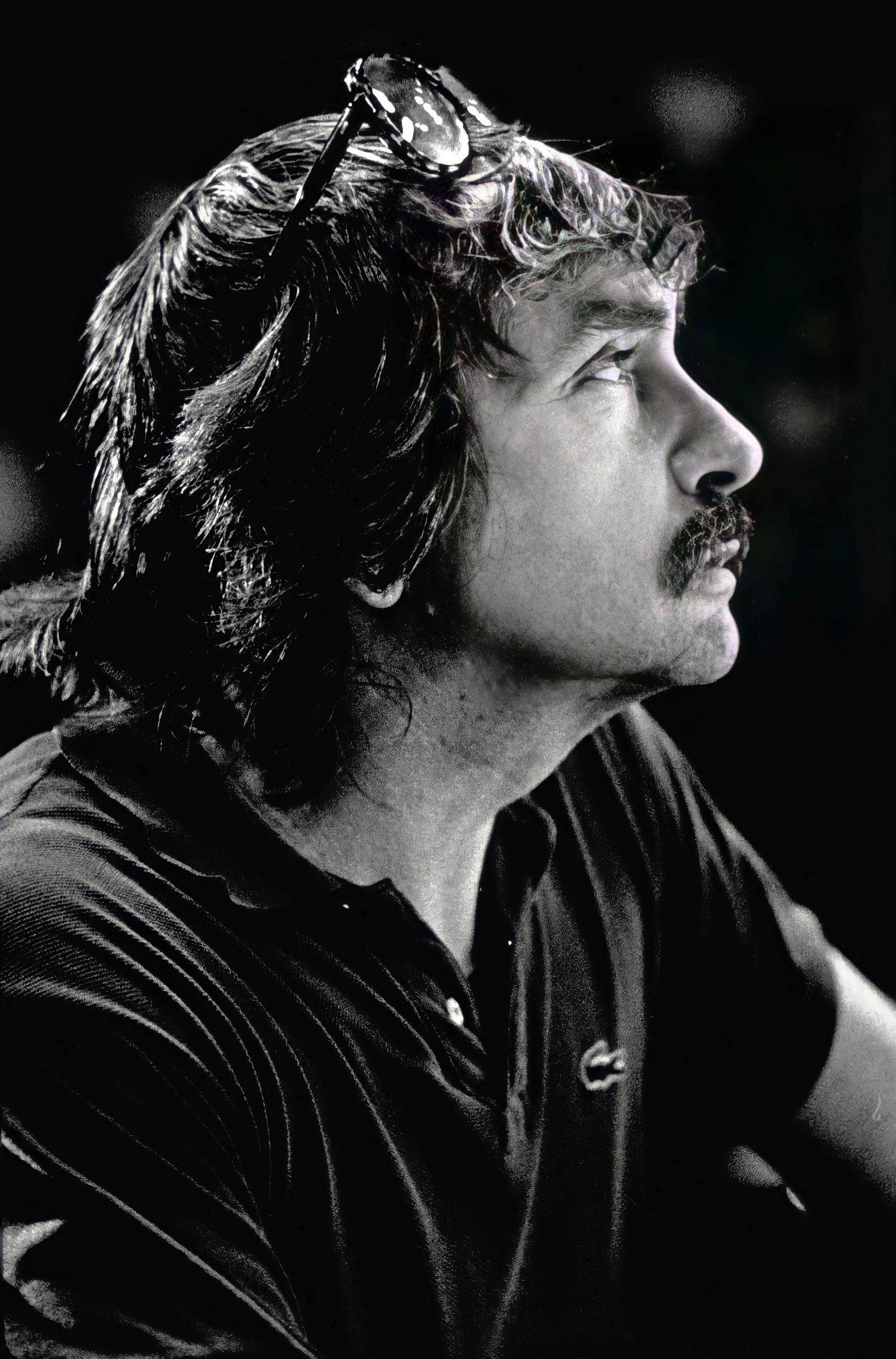

Edward Albee was born Edward Harvey in Washington, D.C. At the age of two weeks, he was adopted by Mr. and Mrs. Reed Albee of Larchmont, New York, and renamed Edward Franklin Albee III. From an early age, Edward Albee knew that he was adopted, but he has never attempted to locate his birth parents.

The Albees enjoyed wealth and social position from the family’s interest in a national chain of theaters. The Keith-Albee organization had played a dominant role in the American theater since the 19th century, from the days of vaudeville and the great touring companies and into the era of motion pictures, when the chain merged with two other companies to become Radio-Keith-Orpheum, the parent company of the RKO motion picture studio.

Through his family’s business, Edward Albee was exposed to the theater at an early age and developed a passionate love for the arts, but his adoptive parents expected him to pursue a more conventional business or professional career. From the beginning, he found himself at odds with his adoptive family over their expectations for him and his own artistic ambitions.

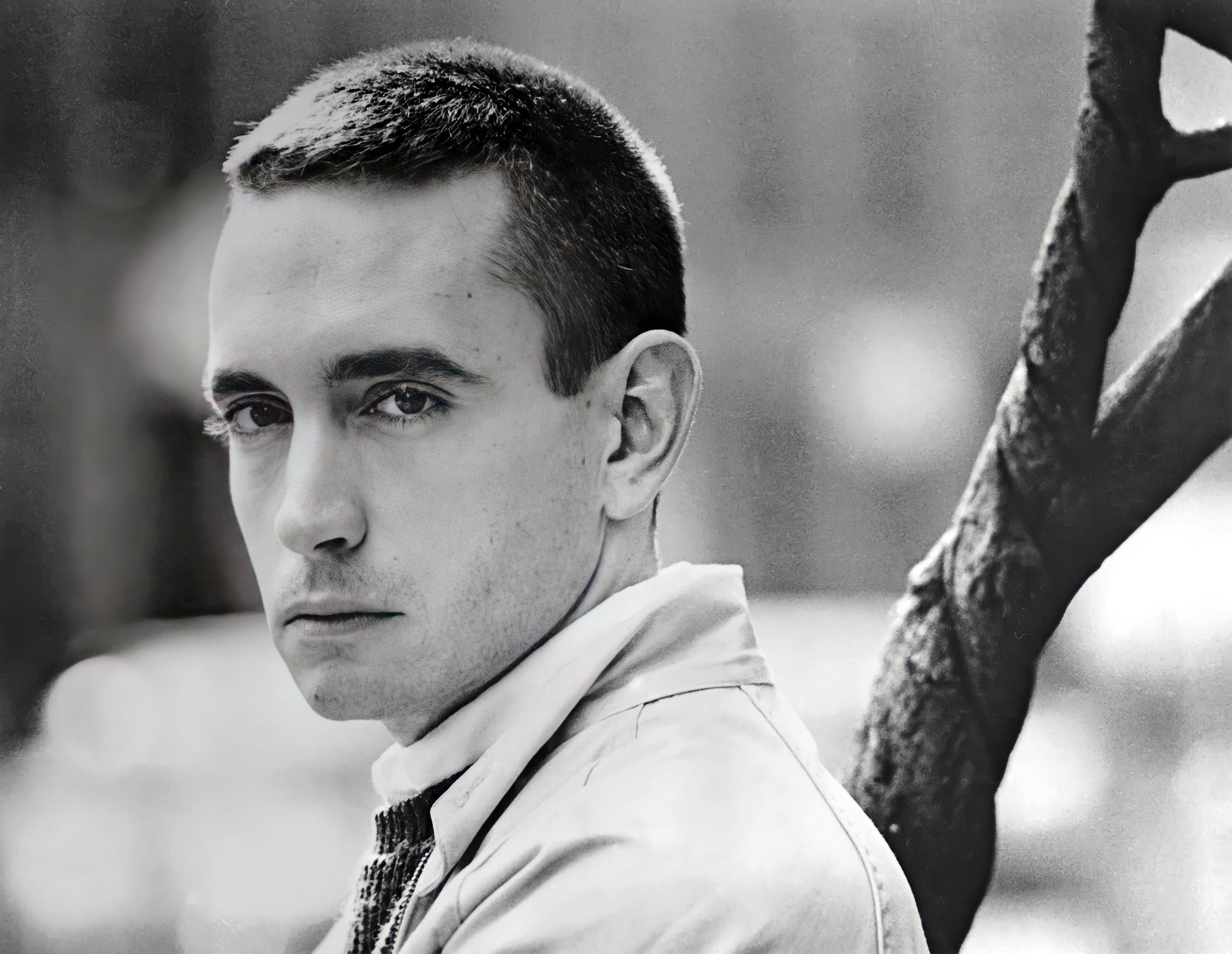

He was expelled from two private schools before graduating from Choate, and dropped out of Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut midway through his sophomore year. At 20, he broke with his family and moved to Greenwich Village. He never saw his father again, and would not see his mother for 17 years.

For the next decade, Albee lived off of a small inheritance from his grandmother, supplemented by a succession of odd jobs, such as one delivering telegrams for Western Union. Enthralled with the artistic ferment of Manhattan in the 1950s, he absorbed every innovation in art, music, literature and the theater. After unsuccessful experiments with poetry and fiction, he finally found his calling in writing for the theater.

At age 30, he completed his first major work, The Zoo Story. The play received its world premiere in Berlin, Germany in 1959, and opened Off-Broadway the following year. This startling one-act, in which a loquacious drifter meets a conventional family man on a park bench and provokes him to violence, won Albee an international reputation as a fearless observer of human alienation. Albee brought absurdism to the American stage with his one-act plays The Sandbox and The American Dream. In the same period, he dramatized America’s simmering racial conflict in a more conventionally realistic short drama, The Death of Bessie Smith.

In only a few years, Albee emerged as the leading light of the burgeoning Off-Broadway movement. By 1962, he was ready to storm Broadway, the bastion of commercial theater in America. His first Broadway production, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, was a runaway success and a critical sensation. The play received a Tony Award, and Albee was enshrined in the pantheon of American dramatists alongside Eugene O’Neill, Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams.

A searing evening in the company of two unhappy married couples, Albee’s play also drew its share of criticism. When the Pulitzer Prize drama panel voted to award Albee the year’s drama prize, the Pulitzer Committee overrode their choice on the grounds that the play did not represent a “wholesome” view of American life. No drama prize was awarded that year and half of the drama jurors resigned in protest. History has long since vindicated their original judgment. In the four decades since its debut, the play has been produced around the world, and is now regarded as an indispensable classic of modern drama.

Albee’s adoptive father, Reed Albee, died before the success of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, but in 1965, Edward Albee attempted a reconciliation with his adoptive mother, Frances. Relations between the two were never easy, but Albee worked hard at the relationship until his mother’s death in 1989. With the profits from Virginia Woolf, Albee created the Edward F. Albee Foundation in 1967. The foundation sponsors a summer artists’ colony in Montauk, Long Island, where the playwright owned a summer home.

Albee’s work in the 1960s ranged over a wide variety of forms and styles, from straightforward literary adaptations, such as a stage version of Carson McCullers’s novel Ballad of the Sad Café, to frankly experimental works such as the one-acts Box and Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung. The violently anti-clerical allegory Tiny Alice was met with responses ranging from frank bafflement to outright hostility when it opened in 1965. Albee made one brief, unhappy foray into musical theater with an adaptation of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, canceled before it even opened.

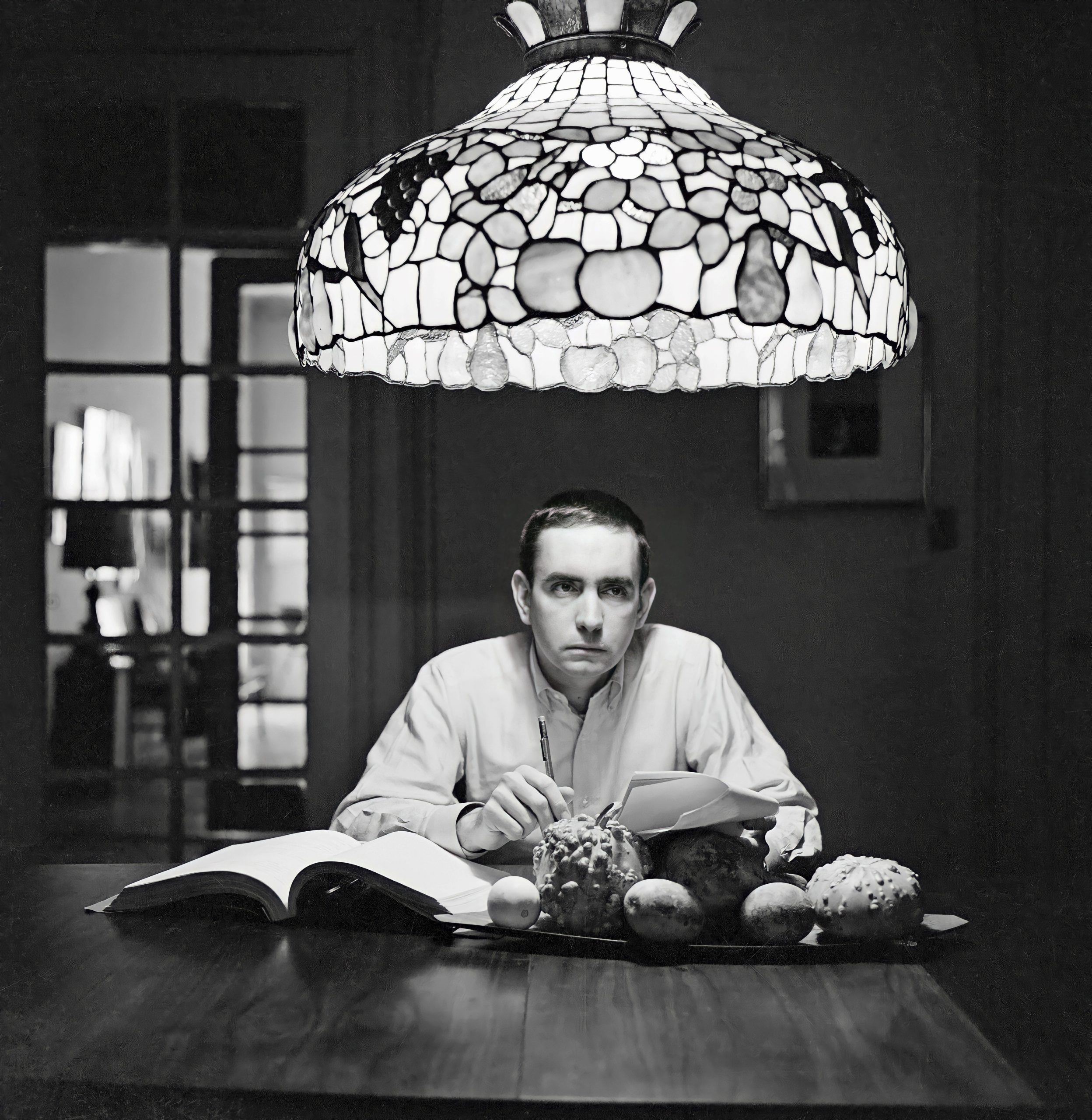

The Pulitzer Committee finally honored Albee in 1967 for his metaphysical drawing room drama A Delicate Balance. Another play dealing with two troubled couples, A Delicate Balance tempered the apparent realism of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf with a faint touch of the absurdism of Albee’s early one-acts. It foreshadowed the technique of many of his later works, in which improbable situations, expressionistic devices or elements of fantasy mingle with utterly realistic characters and dialogue. For many years, Albee was unable to repeat the success he had enjoyed with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, but he continued to engage difficult subject matter, as in All Over (1971), a stark look at death and the aging process. Albee won back the New York audience with Seascape in 1975, an expressionist fantasy in which two couples meet on the beach at Montauk. One couple is human; the other, a pair of anthropomorphic lizards who discuss love, relationships, and the evolutionary process. As bizarre as the idea sounded on first hearing, the result was both humorous and moving. The play charmed audiences and critics and won Albee his second Pulitzer Prize.

After Seascape, the New York theater turned its back on Albee again. In the 1970s, he was drinking heavily and had fallen far behind in his taxes. Ready at last to curtail some of the excesses of his youth, he quit drinking and embraced a more sober and disciplined way of life. Critics and audiences remained lukewarm to his work for much of the next decade. Plays such as The Lady from Dubuque (1980) and The Man Who Had Three Arms (1983) had their admirers, but met with outright critical hostility and enjoyed only limited runs. Nearly 15 years passed without a new Albee play enjoying a successful run in New York, but Albee remained committed to the theater, serving on the board of the Dramatists’ Guild and directing revivals of some of his earlier plays.

In an era of Hollywood-style “play development” by committee, Albee remained an uncompromising defender of the integrity of his own texts and a champion of the work of younger authors. Over the years, he scrupulously reserved part of his time for the training of younger writers. He conducted regular writing workshops in New York, and from 1989 to 2003 taught playwriting at the University of Houston. He persistently asked young writers to hold themselves to the highest artistic standards and to resist what he saw as the encroachment of commercialism on the dramatic imagination.

Edward Albee made a triumphant comeback with Three Tall Women in 1994. Praised by many critics as his best play in 30 years, it struck many students of Albee’s work as a final coming to terms with the memory of his vital but domineering adoptive mother. The play won every award in sight and earned Albee his third Pulitzer Prize. In 1996, Albee was one of the recipients of the Kennedy Center Honors and was awarded the National Medal of Arts.

Albee enjoyed a resurgence of creativity at century’s end. The Play About the Baby (1998), was followed by a surprising success, The Goat or Who Is Sylvia? (2002). The same year, Albee, a passionate art-lover, unveiled Occupant, a dramatic study of the sculptor Louise Nevelson. Unexpectedly, he revisited the characters of his first play, The Zoo Story, in a new work, Homelife, to be performed with The Zoo Story under the collective title Peter and Jerry.

A revival of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? was one of the hits of the 2004-2005 Broadway season. Although the play had enjoyed many successful revivals over the decades, its return to Broadway in the 21st century prompted critical re-evaluation of his long career. Days after his interview with the Academy of Achievement, the American Theater Wing presented Edward Albee with a Special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement, recognizing him as America’s greatest living playwright.

Peter and Jerry reappeared in yet another incarnation as At Home in the Zoo in 2009. In a later work, Me Myself and I, a painfully narcissistic mother and her sons, identical twins both named Otto, struggle with troubling questions of kinship and identity. Me Myself and I opened at New York’s Playwrights Horizon in 2010. Admiring reviews and enthusiastic audiences confirmed that in his ninth decade, Albee’s work had lost none of its power. Edward Albee’s status as America’s greatest living playwright remained unchallenged at the time of his death in 2016.

In the years since his death, Edward Albee’s plays continue to be performed around the world as directors and actors vie for the opportunity to interpret his creations for new audiences. A revival of his 1994 play Three Tall Women was a highlight of the 2018 Broadway season. The actresses Glenda Jackson and Laurie Metcalf received the year’s Tony Awards for Best Performances by a Leading Actress and by a Featured Actress, for their work in Three Tall Women, demonstrating once again the enduring power of the drama of Edward Albee.

Edward Albee exploded onto the theater scene at the end of the 1950s with plays that foreshadowed the turbulence of the decades to come. Adopted as an infant, he rebelled against his socially prominent adoptive family, and fled to Greenwich Village to pursue a literary career. His 1959 play The Zoo Story and 1960’s The Death of Bessie Smith won him an early reputation as a fearless observer of human alienation and the American scene.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf provoked an unprecedented controversy in 1962 when the trustees of the Pulitzer Prize Committee overrode the judgment of their own drama jury to deny Albee the award, but Albee’s unblinking portrait of a tortured marriage has long since become an undisputed classic of world drama. The Pulitzer Committee soon honored Albee for another family drama, A Delicate Balance, in 1966, and awarded him a second prize for Seascape in 1975.

While the Broadway stage turned away from serious drama in the 1980s, Albee ignored the fads of the moment and maintained his own high standards. Three Tall Women enjoyed a sold-out New York run in 1994 and earned him his third Pulitzer. His 2002 success, The Goat or Who Is Sylvia?, once again demonstrated his unique gift for treating the most unusual and disturbing matter with clear-eyed humor and humanity. And more than 40 years after its premiere, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf was back on Broadway, as powerful as ever.

What was it like for you growing up in and around New York City as a kid?

Edward Albee: I was an adopted kid, and I was raised by this wealthy family who had been involved in theater management — vaudeville management, the Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit. And so, the house would be filled with retired vaudeville performers all the time. So, I got to meet Billy Gaxton, Victor Moore and Ed Wynn, and all those people that nobody’s ever heard of. And, I started going to the theater when I was really young. I think when I was six years old I went to see Jumbo at the old Hippodrome theater, that musical with Jimmy Durante and an elephant. That was my first experience in the theater. So I was raised on live theater, which was about the only good thing about the adoption.

How would you describe yourself as a kid?

Edward Albee: Forming myself, I suppose.

I never felt comfortable with the adoptive parents. I don’t think they knew how to be parents. I probably didn’t know how to be a son, either. And, I stayed pretty much to myself. I had a fairly active inner life. I certainly didn’t relate to much of anything they related to. They sent me away to school when I was nine, ten years old, not to have me around. So that was fine. It was all right. I took care of myself.

Did you like school?

Edward Albee: Yes, I liked school, only when I was doing the stuff that I wanted to do. I was always very, very good at the classes that interested me and very bad at the ones that didn’t. I think I knew very, very young — or at least had some inkling of — the direction that my life was going to take. I was always interested in the arts. I started painting and drawing when I was eight years old and writing poetry when I was nine or 10. I wanted to be a composer after I discovered Bach when I was 12 and a half, but that didn’t work out. He was too good!

How do you explain that? Why do you think you knew what you wanted to do at such a young age?

Edward Albee: I don’t know. Obviously, it’s the way my mind works, or worked at the time. Those things interested me. I have no idea who my natural parents were. Back in the days when I was adopted, you weren’t allowed to find that sort of thing out. So I couldn’t. But I don’t think that matters much, anyway. Some of the brightest kids that I’ve known, I’ve met their parents and I can’t believe that there was any relationship between them.

When you were growing up, were there any books that were important to you? What did you read?

Edward Albee: I read as much as I could. I have a funny story. The family had a big library in their huge house in Larchmont, leather-bound books. And, I was looking for a book to read one night. I was 14, maybe 13. Who was this Ivan Tur-gun-eff? Turgenev, of course. So, I took one of the books out of the library. It was Virgin Soil, as a matter of fact, and I read it. And the next morning I came down for breakfast — the family had to have breakfast together, it was a formality — and they were rather cool, I thought. I said, “What’s the matter?” They said, “There is a book missing from the library.” I said, “Yes, it’s by Ivan Tur-gun-eff, ” not pronouncing his name correctly. “And it’s a wonderful book. I took it upstairs…” “It belongs in the library. You have left a gap on the shelves.” That gives you some idea of the disparity between our points of view.

What was it about your early family life that troubled you?

Edward Albee: I never felt that I related to these people, which may be interesting, because most kids are trapped into feeling an obligation to their natural parents. For what? For being born, I guess. Foolish notion, but still. And, since I didn’t relate to these people, and I knew that I wasn’t from them, I had a kind of objectivity about the whole relationship. This is all second-guessing, of course, but I suspect it probably was in my mind. I am a permanent transient. That’s probably where that line in The Zoo Story came from! “I’m a permanent transient. My home is the sickening rooming houses on the Upper West Side of New York City, which is the greatest city in the world. Amen!” I bet that’s where that line came from — in The Zoo Story.

You weren’t exactly a poster child for success in school, we understand.

Edward Albee: Well — no.

I got thrown out of a lot of schools, yeah, because I didn’t want to be there. I didn’t want to be home either. I didn’t want to be anywhere I was. But, I managed to get an education before I got thrown out, in the stuff that interested me. Teachers seemed to sense that, in some terribly unformed way, there might be something going on in the mind there that should be encouraged. So, they would encourage me towards the things that interested me. And, that was nice. So, I’d learn something at one school, get thrown out, go to another and learn some more.

Were there teachers who influenced you? Who were important to you?

Edward Albee: Oh sure.

There were some teachers who were very, very helpful and, as I say, sensed that maybe I had a mind worth cultivating, and pointed me in the right direction to a lot of things. I can’t be specific about it, but I know that was going on. These are all private schools, not public schools in the bowels of the city. These were private schools, a lot of wealthy kids there. But, the teachers were paid fairly well, and they were better educated than their students — which is not necessarily true in many of our public school systems now — and some bright people. They had small classes — seven or eight kids in a class — and they could spend time finding out who the kids were. I’m very, very grateful that, even though I didn’t get along with my adoptive parents, they did offer me an extraordinarily good education.

You say you started writing poetry at eight or nine.

Edward Albee: Yeah. I’d already started drawing before then.

What do you think motivated you to do that?

Edward Albee: Probably because I thought I was a painter, and I thought I was a writer.

You left college early, didn’t you?

Edward Albee: Yes, I did. It was a mutual agreement.

I was not going to many of the courses I was supposed to in my freshman and sophomore year. I was going to a lot of interesting courses the seniors were taking, getting a good education on a graduating level, and of course, being marked absent and failing my required courses. They didn’t like that. And, they gave me a choice: go to the courses I was supposed to, or leave. So I left. I was the one being educated; I thought I should have some say as to the nature of my education. Foolish notion.

You also left home for good after that, didn’t you?

Edward Albee: Yes, I did. I tried first when I was 13, because one of my grandmothers had given me little Christmas presents, and I had a few hundred dollars. So I went into New York with my little suitcase and tried to get on an ocean liner — Cunard, or whatever the line was — and discovered that I didn’t have enough money. Also, I didn’t have any identification or anything, and they weren’t going to let me on board the ship.

Where did you want to go?

Edward Albee: Anywhere. London or Paris, probably Paris. But that didn’t work out. So I waited until we were so completely fed up with each other there was nothing for it.

When you left home, you went to Greenwich Village in New York City. What were you looking for?

Edward Albee: I guess I’d been told that Greenwich Village was where whatever intellectual ferment was going on in New York was going on. That’s where all the interesting people were. So I went there.

And you found it?

Edward Albee: Yeah. It was very easy in those days. Nobody had agents. Nobody was famous.

What did you do when you got there?

Edward Albee: I completed — or not completed — continued my education, by going to see all the great abstract expressionist paintings, and listening to all the contemporary music up at Columbia at McMillan Theatre, going to see all the wonderful Off-Off-Broadway plays. The paperback book market was around, so when I couldn’t steal a book I could buy it real cheap. It was good. And, there were a lot of saloons that we all went to, all the writers. All the painters, of course, would go to the Cedar Bar, and you would go there and watch them fall down. It was sort of nice. And, then all the writers would be going to — what was that bar on the corner of Bleecker and McDougall called? San Remo. Everybody would be there, sitting around talking. And, if you wanted to be with the young composers you’d go up to the Russian Tea Room — not the Russian Tea Room — there was a bar on the southwest corner of Carnegie Hall. I forget what it was called. And, all the composers would be there. We all knew each other. Everybody was friendly. Yeah, it was a nice time.