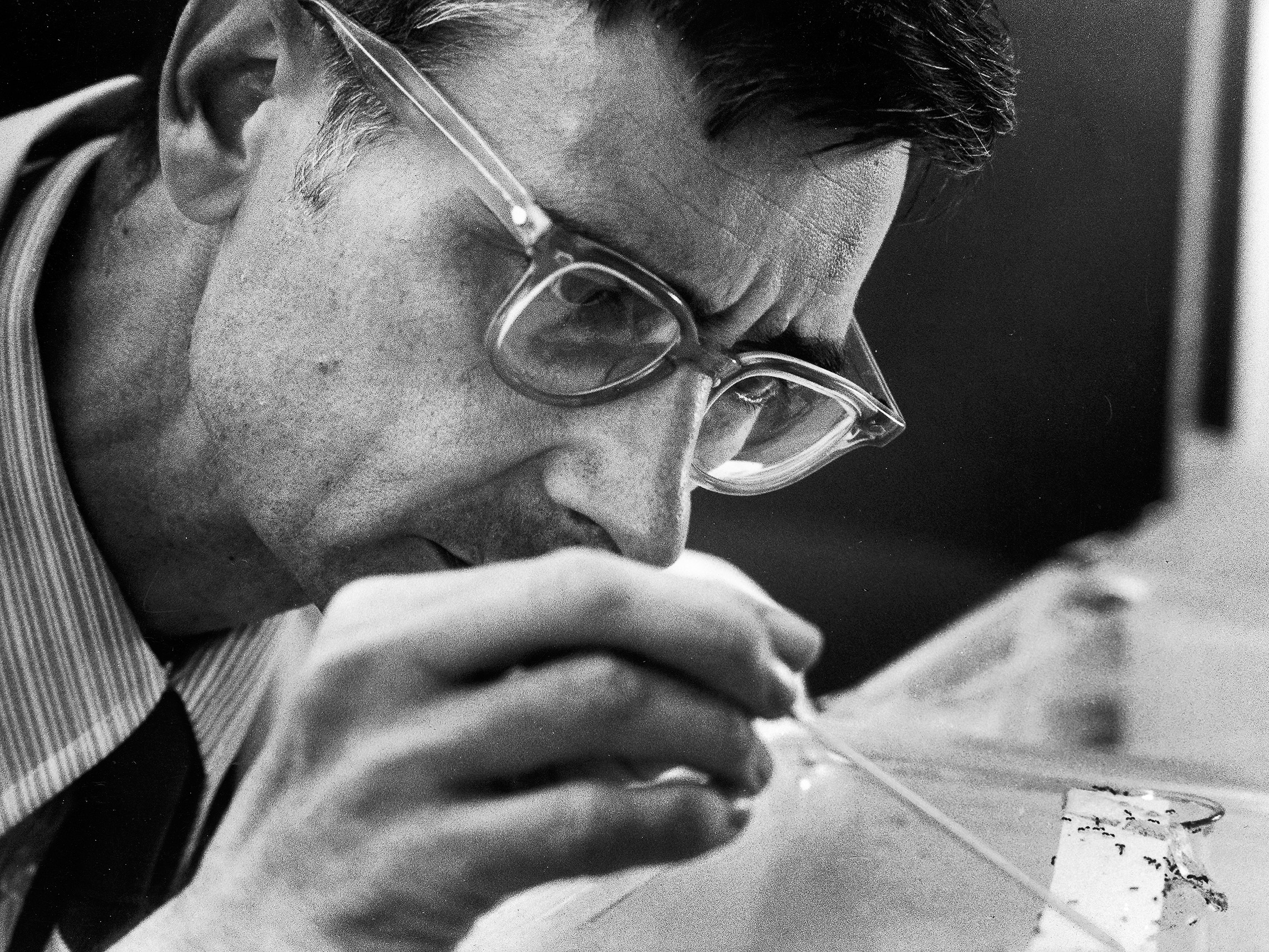

I had a bug period like every kid. I just never outgrew mine. I had a kid's natural inclination to explore the environment...Part of the reason was I was an only kid, partly because I could see in only one eye...So, I tended to look very closely at things that were very small.

Edward Osborne Wilson was born in Birmingham, Alabama. His father, a government accountant, moved the family frequently, as he was reassigned from Washington, D.C. to Florida, Georgia and Alabama. Lacking steady friends, the young Edward found companionship in nature, exploring Rock Creek Park in Washington, and the wilds of the Deep South. At age seven, while fishing, the fin of a spiny fish scratched his right eye, permanently impairing his distance vision and depth perception. He enjoyed acute near-distance vision with his left eye, and used it to examine insect life at close range. By age 11, he was determined to become an entomologist. When a wartime shortage of pins interrupted his collecting of flies, he turned his attention to ants, which could be stored in jars, and set himself the task of cataloguing every species of ant to be found in Alabama.

At age 13, Wilson discovered a colony of non-native fire ants near the docks in Mobile, Alabama and reported his finding to the authorities. By the time he entered the University of Alabama, the fire ant, a potential threat to agriculture, was spreading beyond Mobile, and the State of Alabama requested that Wilson carry out a survey of the ant’s progress. The resulting study, completed in 1949, was his first scientific publication. Wilson received his master’s degree at the University of Alabama in 1950, and after studying briefly at the University of Tennessee, transferred to Harvard for doctoral studies.

Wilson was made a Junior Fellow of Harvard’s Society of Fellows, an appointment that enabled him to pursue field research overseas. He embarked on a number of expeditions in the tropics, exhaustively collecting the ant species of Cuba and Mexico before moving on to the South Pacific. His scientific travels would take him from Australia and New Guinea to Fiji, New Caledonia and Sri Lanka. In 1955, he received his Ph.D. from Harvard and married Irene Kelley. The following year, he joined the Harvard faculty, a relationship that was to last his entire career.

In the first of many contributions to our understanding of species evolution, Wilson tracked the evolution of the hierarchical caste system among ants. Comparing his observations of the ants of the South Pacific with the extensive collection in Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, he then devised the theory of the “taxon cycle” to explain how ants adapt to adverse environmental conditions by colonizing new habitats and splitting into new species. The same pattern has since been observed among other insect and bird species.

By the end of the 1950s, Wilson had won recognition as the world’s foremost authority on ants, but his studies in taxonomy and ecology ran contrary to prevailing fashion. The discovery of the DNA molecule by James Watson and Francis Crick had focused the biological community’s attention on the molecular basis of life and away from natural history and the study of species evolution. Watson went so far as to compare natural history to stamp collecting. Wilson knew better, and deployed advances in microchemistry to inform the traditional practices of natural history. Collaborating with the mathematician William Bossert, he investigated the phenomenon of chemical communication among ants. Wilson and Bossert identified the chemical compounds, known as pheromones, that permit ants and other species to communicate by sense of smell.

In the 1960s, Edward Wilson enjoyed a fruitful collaboration with mathematician and ecologist Robert MacArthur. Together, they attempted to apply the theory of species equilibrium to the contained environment of small islands. The resulting book, The Theory of Island Biogeography, is now a standard work of ecology, and informs conservation policy and the planning of nature reserves around the world. Wilson effectively demonstrated the theory through a remarkable experiment. After eliminating the existing insect population of a tiny island in the Florida Keys, Wilson observed the repopulation of the island by new species, confirming the principles of island biogeographic theory.

Wilson synthesized his enormous body of knowledge on the social insects — ants, bees, wasps and termites — in his masterful work, The Insect Societies, published in 1971. This work invoked the evolving concept of sociobiology, the study of the biological basis of social behavior among different organisms. In 1973, Wilson was appointed Curator of Insects at the Museum of Comparative Zoology. Wilson’s work on the sociobiology of insects was well-received, but his next major work ignited a firestorm of controversy.

In Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (1975), Wilson extended his analysis of animal behavior to vertebrates, including primates, and in the last chapter, humans. Wilson speculated that hierarchical social patterns among human beings may be perpetuated by inherited tendencies that originally evolved in response to specific environmental conditions. A number of Wilson’s colleagues took strong exception, and others condemned Wilson’s work on the grounds that it justified sexism, racism, polygamy and a host of other evils. Although Wilson adamantly denied any such intent, demonstrators picketed his lectures, and in one instance protesters doused him with water during a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Through the commotion, Wilson stood his ground, and in 1978 published a highly acclaimed work, On Human Nature, in which he thoroughly examined the scientific arguments surrounding the role of biology in the evolution of human culture. Wilson was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction for his graceful and lucid explanation of his ideas. By the end of the decade, the furor over sociobiology had subsided and researchers in many fields now accept Wilson’s ideas as fundamental.

In the decades that followed, Edward Wilson continued to extend the domain of his interests. With collaborator Charles Lumsden, he published Genes, Mind and Culture (1981), introducing the first general theory of gene-culture co-evolution. He followed this with the intriguing Promethean Fire: Reflections on the Origin of Mind (1980). Wilson explored the bond between man and nature in Biophilia, a title that introduced yet another new term to the language of science. Wilson revisited his first scholarly love in The Ants (1990), co-written with Bert Hölldobler, a monumental work that brought Wilson his second Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction.

Over the years, Wilson has been an active participant in the international conservation movement, as a consultant to Columbia University’s Earth Institute, and as a director of the American Museum of Natural History, Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy and the World Wildlife Fund. In the 1990s, he continued to write and publish at a tremendous rate. His published works in this decade included The Diversity of Life (1992) and a memorable autobiography, Naturalist (1994). Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (1998) outlined his view of the essential unity of the natural and social sciences.

Edward Wilson officially retired from teaching at Harvard in 1996. He continues to hold the posts of Professor Emeritus and Honorary Curator in Entomology. Since retiring from teaching, Wilson has continued to write prolifically. His later books include Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth; and Nature Revealed: Selected Writings, 1949-2006. In 2013, he published Letters to a Young Scientist, a memoir in the form of 21 letters, in which he distills 60 years of teaching and a lifetime of experience. He and his wife Irene still make their home in Lexington, Massachusetts.

Edward O. Wilson’s childhood fascination with insects and other living things matured into an intellectual passion that fired one of the greatest careers in modern science. Wilson made his first major entomological discovery at age 13. By the time he completed graduate school he was already winning recognition as the world’s foremost authority on ants. From his base at Harvard University, he traveled the world, collecting rare specimens and gaining unprecedented insight into the evolution and behavior of these complex creatures.

Wilson pioneered the study of chemical communication among animals and devised the theory of island biogeography that informs conservation practice to this day. His landmark studies of the social insects became a cornerstone of the modern science of sociobiology, the systematic study of the biological basis of social behavior. In his 1975 book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, Wilson applied this discipline to the behavior of all species. His observations on the biological origins of human nature and society stirred a maelstrom of debate. Wilson endured bitter personal attacks from critics, many of whom grossly misinterpreted his work, but within a few years, his ideas had won widespread acceptance throughout the scientific community.

A graceful and lucid writer, Wilson holds the distinction — especially rare for a scientist — of winning two Pulitzer Prizes, awarded for On Human Nature and the comprehensive work The Ants. Over the course of his career, Wilson has written over 20 books and discovered hundreds of new species. His ideas have had an immeasurable influence on our understanding of life, nature and society. He remains an outspoken advocate for conservation and biodiversity, fighting to preserve the wondrous variety of the natural world.

Dr. Wilson, in the 1960s you made a departure from the historic practice of natural history, conducting an experiment in species immigration and extinction. What was your intention?

I wanted to make evolutionary biology experimental, and no one had thought of making biogeography experimental. How could you make biogeography experimental? And it dawned on me — because I was doing all this field work, more from the experience of natural history — that we weren’t going to be able to experiment with New Guinea or Fiji, or even a small island in the West Indies. Because what I had in mind was to eliminate all the species in a place where they could be eliminated without any real damage to the total fauna, and then study the return of those, and see how that accorded with the basic patterns predicted by the theory of island biogeography. And it dawned on me that whereas you have to have an island the size of Cuba, say, for a real population of woodpeckers or small mammals, that a very small island, like a mangrove island in the Florida Keys, would be an island for tiny insects where thousands of a species could live.

I arrived at the Florida Keys by looking at maps, detailed maps. I went up and down the East Coast, looking at different islands — rocky islands and sandbars and so on, and then I finally came to the Florida Keys, where I had done field work before — and it dawned on me. There are these thousands of little mangrove islands in Florida Bay.

In fact, there is an area called the Ten Thousand Islands, and my idea first, which I started in 1965, was to go down to the Dry Tortugas and survey and map every plant and animal on those little sandy islands off Key West and then wait for a hurricane to wipe them clean — because we know every time that a hurricane passed through there, they were wiped clean of life — and then I would go back and study them. We actually got that started. We even had a couple of hurricanes conveniently occur that season, but I realized that that wasn’t going to do it. So I had to figure out a way of eliminating all these little arthropods.

Weren’t the hurricanes efficient enough?

Edward O. Wilson: We didn’t get them frequently enough, and you couldn’t control it. We couldn’t have controlled experiences. We had to do better than that. We had to find a way of eliminating all the arthropods, essentially all animal life, from a small key, maybe 50 to 75 feet across. About this time, I had the great good fortune of being joined by Dan Simberloff, who had been trained in math. He had just become a naturalist at this point, in order to do this experiment. Dan and I plotted how to set this experiment up. Without going into too much detail, it was quite an adventure, our mishaps, our false starts…

Lining up an exterminator, getting the right technique… we pulled it off. We actually followed the recolonization of an empty island, in fact a whole series of them, with controls, and that was the first experiment in island biogeography. And although the data had certain limitations — we couldn’t really figure out the turnover rate exactly — we did affirm the main conclusions of the theory of island biogeography. The closer the island is and the smaller it is, the more quickly it fills up. The farther away it is, the larger it is, the more slowly it fills up. We learned a lot about the colonization of our islands in that experiment. It was very satisfying.

Your book, Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, caused quite a firestorm. Many people objected to your suggestion that hierarchical behavior in humans may have evolved in response to environmental conditions, as animal behavior does. Were you at all nervous about publishing it? Darwin, we know, was apprehensive about publishing The Origin of Species.

Edward O. Wilson: I wasn’t as scared as he was. I just never realized that a storm would erupt over that. He was afraid of the religious response, and I didn’t know or care about the Marxists or the current dominant ideology.

So you were caught really by surprise.

Edward O. Wilson: I caught them by surprise, (by) including humans, and I saw right then and there that this could be very important, to include humans in this. I caught them by surprise, and then they caught me by surprise because I didn’t expect to be blindsided, literally, from the left. I won’t go into all of that, except to say that it was a period in which the whole subject came close — that is, as it applied to humans — came dangerously close to being politicized. It was politicized. The animal part was enormously successful. It resulted in a couple of new journals, a very substantial increase in the studies of animal social behavior. It was accompanied by an explosive growth of behavioral ecology, a closely related subject which included solitary animals and their behavior. At one point, the Animal Behavior Society voted Sociobiology: The New Synthesis the most important book on animal behavior ever, even got more votes that Darwin’s book. But I think so many of the social scientists, philosophers, and particularly those who were defending a Marxist ideology, considered it the worst book on human behavior in history, or one of them, and it was a tumultuous period in which what they considered the dangers of returning biology to the consideration of human behavior were too great to be tolerated.

It’s surprising, re-reading that last chapter of Sociobiology now, 25 years later. It seems so innocuous. It’s hard now to see what the fuss was all about. Was it the political climate of the time?

Edward O. Wilson: Oh, that is exactly right. 1975 was the last year of the Vietnam War. It was also the twilight of the New Left in the academy, which had become almost dominant and very violent in several respects in the ’60s. It involved a minority of students and professors, but nonetheless, they were so vocal and demonstrative that they tended to rule the learning climate in the academy. It was a very unfortunate trend. The main antagonists — Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin, for example, and several others who organized the movement against it — their idea was to strangle it in the crib. So their language was extremely strong.

Didn’t that backfire on them later?

Edward O. Wilson: I think it quickly backfired.

Today, 25 years later, gradually the malodor drifted away, and today it is one of the most popular subjects, particularly going under the name “evolutionary psychology.” There is an entire library of books it seems, almost every year, published. It never was rejected as heavily as the criticism seemed to indicate — that is, the conspicuous criticism. I made a count not too long ago of books published from 1975 to ’95 — in my library, which is nearly complete — on human sociobiology, and in that period, the books favorable, predominantly favorable, ran something like 20 to one against those that were unfavorable. The ones that were unfavorable were often paid a great deal of attention to because everybody likes a fight.

Nowadays, they have just about gone to nothing. So I think that struggle is largely over.

You really have triumphed with the passage of time. Some of your worst critics have become researchers in the field.

Edward O. Wilson: What was new about sociobiology — and it finally began to dawn — was that, for better or for worse, right or wrong in its basic presumptions, for the first time, That will only happen once, and that was another reason why there was so much trouble. The social scientists weren’t prepared for this. They didn’t understand it, or they think they saw fundamental flaws in it. They thought it was unhealthy. They thought it was hegemonic, and a great many of them still feel that way. That is one reason that I wrote my book Consilience, was to try to show how knowledge might be unified, and in a manner that would mean coalition and cooperation and joint exploration of the big remaining gap, rather than translation of the great branches of learning — the other great branches of learning — into scientific language and scientific rules of validation. Many who resisted Consilience resisted Sociobiology for the belief that somehow the scientists who didn’t really know what they were talking about were coming into the social sciences, humanities, and trying to take over in a destructive way. I hope that Consilience might have moderated that response.

If you had a chance to rewrite the last chapter of Sociobiology now, knowing the controversies that ensued, would you have written it differently? Do you think it would have made any difference?

Edward O. Wilson: I would have written it differently. I think I would have written a much longer chapter, and of course, I would have been ignorant of so many things we know today in terms of how biology and culture might interact. I didn’t start studying that until about four years afterwards anyway, myself, but I certainly would have taken a very cautious tone, and I would have put in a lot about the political dangers on both sides. I would have tried to bulletproof myself from the left, and at the same time, I would have made concessions to the left about the high risk of misuse of any kind of biology on the right. I think that would have defused a lot of it, but I think there would have been a strong controversy. There wouldn’t have been the one coming from my colleagues here quite as strong anyway, because that would have disarmed them.