You take pieces you love and then you fashion a life out of it, rather than looking for the pieces to fit some particular mold.

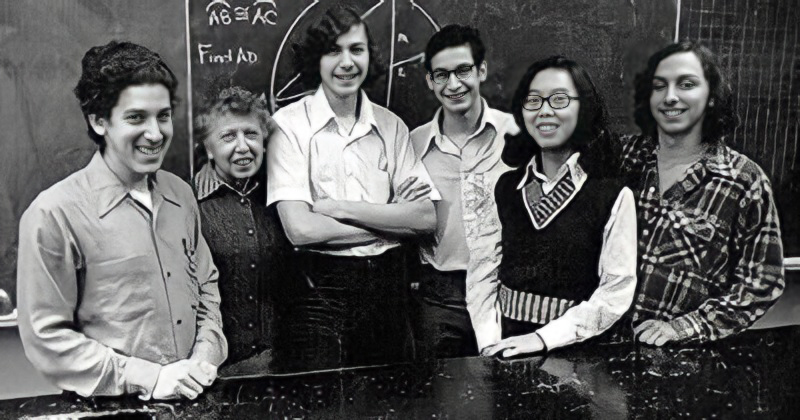

Eric Steven Lander was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. His father was disabled by multiple sclerosis through much of Eric’s childhood and died when Eric was 11. Although Eric’s mother had been trained as an attorney, opportunities for women lawyers were few at the time, so she worked as a teacher to provide for Eric and his younger brother Arthur. In junior high school, Eric became fascinated by mathematics. At New York’s Stuyvesant High School — a public school specializing in math and science — Lander led the school’s math team, and won a silver medal for the United States in the International Mathematical Olympiad. At age 17, a paper he wrote on quasiperfect numbers won the national Westinghouse Science Talent Search. He participated in the American Academy of Achievement’s 1974 Salute to Excellence program in Salt Lake City as a student delegate.

Lander continued to excel in mathematics as an undergraduate at Princeton University, but he also found time to work as a reporter on The Daily Princetonian. Intrigued by politics, polling and statistics, he persuaded the Gallup organization to support his poll of university students in the 1976 presidential election. In an elective class on constitutional law, he met fellow student Lori Weiner for the first time. Eric made a point of joining campus committees and other activities Weiner was involved in. The two became friends quickly, but romance blossomed more slowly.

Eric Lander graduated from Princeton in 1978. He was valedictorian of his class and was awarded the Pyne Prize, the university’s highest undergraduate honor. He pursued graduate studies at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, studying combinatorics and applications of representation theory to coding theory. He completed his Ph.D. thesis on symmetric design but had grown restless in the world of pure mathematics. On returning to the United States, he was certain he wanted to marry Lori Weiner but was less sure how to apply his training in mathematics.

Rather than consulting his former math professors at Princeton, he sought advice from the university’s political scientists and statisticians, who urged him to try his luck in Boston, where the large concentration of universities might lead to unexpected opportunities. To his surprise, Lander was offered a job as lecturer in managerial economics at Harvard Business School. The field was new to Lander, but he plunged ahead, and became a popular lecturer and professor. He married Lori, and the two started a family.

Although Lander enjoyed his teaching duties at Harvard, he had not found the career he was looking for. He was completing a book on information theory when his brother, Arthur, now a physician and neurobiologist, suggested he apply this interest to the most complex information system of all — the human brain. The proposal excited Eric Lander, but the more he explored the subject, the more he felt the need for basic training in biology. At Harvard, the business school professor sat in on undergraduate lab classes taught by graduate assistants. He quickly came to enjoy laboratory work and began to moonlight in the molecular genetic laboratory. Lander took a leave of absence from Harvard to pursue genetics research at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). His mathematics background proved invaluable in identifying the minute genetic variations that predispose individuals to a host of disorders, including cancer, diabetes, schizophrenia and obesity.

Lander made the rounds of international conferences, speaking on the application of mathematics to genetics. In 1986, he joined the MIT-affiliated Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research. The following year he received a MacArthur Fellowship — often called the “genius grant” — to further develop mathematical techniques of genetic analysis. He was offered tenured positions in the biology departments at both Harvard and MIT. He accepted the position at MIT first, although his subsequent career has bridged both institutions.

The professor of managerial economics had become a professor of biology, but his management studies did not go to waste. In 1990 Lander founded a new Center for Genome Research at Whitehead and MIT (WICGR). The new center became a major partner, with the National Institutes of Health and other research labs, in the international Human Genome Project (HGP). The HGP intended to make its data freely available to the public, and soon found itself in a race with the for-profit company Celera Genomics, which planned to patent its findings.

Lander pushed his team to complete their work ahead of schedule, developing new methods for sequencing human genes. The target date moved from 2005 to 2003. The public draft of the human genome was published in the journal Nature in 2001, years ahead of schedule. The WICGR was listed first among the article’s contributors, with Eric Lander as the first named author.

The work of Lander’s team at WICGR continued, sequencing genes of the mouse, pufferfish, Neurospora crassa fungus and Sacharomyces cerevisiae yeasts. These organisms are among the most useful for basic medical research, easing the identification of key gene regulatory elements throughout the plant and animal kingdoms.

In 2003, Lander became founding director of the Broad Institute, merging the genome research efforts of the Whitehead Institute, MIT and Harvard. The Broad Institute is dedicated to creating comprehensive tools for genomic medicine, and developing their application to the understanding and treatment of disease. By assembling a catalogue of the variations of the human genome, Lander and his associates are determining which variations are linked to which diseases, identifying precise molecular targets for potential therapies. Lander has developed a molecular taxonomy of cancer, grouping each form of cancer according to gene expression, determining their relative susceptibility to chemotherapy or other treatments. In 2004, Time magazine name Eric Lander one of the “100 Most Influential People of Our Time.”

In addition to directing the Broad Institute, Eric Lander continued to participate in teaching the undergraduate introductory biology course at MIT. Shortly after the 2008 presidential election, president-elect Barack Obama named Eric Lander to co-chair his Council of Advisors on Science and Technology.

In 2021, newly elected President Joseph Biden chose Lander to direct the Office of Science and Technology Policy. For the first time, this office was elevated to cabinet-level, reflecting the new administration’s emphasis on the role of science in public policy and the importance of Dr. Lander’s counsel as the President’s chief science advisor. On January 7, 2022, Lander resigned after the White House confirmed that an internal review found credible evidence he mistreated his staff.

In July 2022, Lander joined a new nonprofit, Science for America, as the organization’s chief scientist. Its mission is to serve as a “solutions incubator” for some of the world’s most pressing problems today. That includes addressing the climate and energy crisis, human health issues like cancer and pandemic preparedness, equity in STEM education, developing new models for innovation, and making America a global leader in critical, cutting-edge technologies like synthetic biology, artificial intelligence, semiconductors, and quantum computing.

From an early age, Eric Lander made a name for himself as a mathematical prodigy, winning the Westinghouse Science Talent Search. Class valedictorian at Princeton, Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, he was poised for a career as a theoretical mathematician. Yet he was dissatisfied. He wanted his research to serve a more immediate human purpose. He embarked on a career teaching managerial economics at Harvard Business School; although he loved the teaching, he found the research unsatisfying.

In the midst of a promising career, with a growing family to support, he dropped everything and made a midlife course correction. Although he was already a professor in the business school, he undertook basic studies in biology. He soon found a new application of his mathematical prowess in the emerging field of genomics, the study of all the genes in a given organism, and their function in sickness and in health.

He played a leading role in the Human Genome Project, and is the first listed author on the article describing the complete human genome published in Nature in 2001. He served as Founding Director of the Broad Institute, a joint project of Harvard, MIT and the Whitehead Institute, where he has led a revolution in our understanding of the nature of life — and the causes and treatment of disease. In 2021, incoming President Joe Biden named Dr. Lander to his cabinet as Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy.

This is not your first visit to the American Academy of Achievement’s annual Summit of young scholars and international leaders. You’ve been here before.

Eric Lander: For me this is a return trip to the American Academy of Achievement. I first came in 1974, as a high school senior, to the American Academy of Achievement after having won the Westinghouse Science Talent Search. And for me it was a very interesting experience. I had grown up in Brooklyn, New York, and really not gone all that far from Brooklyn in my days. Certainly never out West, and certainly never to a place like Salt Lake City, where that particular Achievement Banquet was held. It was remarkable meeting this range of students from all over the country, from so many different cultural backgrounds, meeting large numbers of people who had never heard of a bagel, for example. It was really interesting meeting some of the adult honorees, but I must say I was most struck and most remember the other students, the cross-section of American students I met then. So for me, it was a very eye-opening affair, and it’s really charming and wonderful to be back now, 25 years later, and to look back on myself then, and see myself out in the audience with all these wonderful, bright high school students today. And I think it perhaps gives me just a little bit of a special relationship to talk to them about what their next 25 years may be like. I certainly imagined at the time that I had more of a plan than it turned out I did. I’m trying to give them some notion that, in fact, their lives are probably going to be like that, too. That whatever they’re planning today, the most exciting things that will really happen in their lives are things that don’t even exist yet.

Today you’re known to us as a professor of biology, a leader of the Human Genome Project, but you originally trained as a mathematician.

Eric Lander: After I left graduate school and pure mathematics, I didn’t know what in the world I wanted to do, and by a series of accidents — largely because I’d randomly met some economists and statisticians — I got a job teaching as a professor at the Harvard Business School. Not the sort of thing that usually happens as an accident, but it was a very lucky accident. I taught managerial economics there for nine years.

You say it was an accident that led you to Harvard Business School. Can you talk about that accident?

Eric Lander: Sure. Well, in one sense my own career sounds very linear and straightforward. I was a math whiz in high school. I was a math major in college. I went on a Rhodes scholarship, to do a math Ph.D. A very linear chain. But in point of fact there were wonderful distractions all along the way. When I was in college, my very first week, I came back from a play, stopped in at a beer and pretzel party at the student newspaper,The Daily Princetonian at Princeton. I had a wonderful time and stayed for four years doing journalism. I loved writing. I worked on the newspaper just a vast majority of my time in college. I took a great course from John McPhee, a spectacular nonfiction writer. I was a stringer for Business Week magazine over the summer on an internship. I just really loved it.

One of the things I did was I decided to start a public opinion poll in 1976 for the presidential election. George Gallup’s organization is located in Princeton, and I got up the courage to go across the street and convince the Gallup organization to help us start a student poll, which we did. We involved a number of colleges up and down the East Coast, and launched a public opinion poll. That got me talking to a bunch of economics professors and political science professors and statisticians, and I just made some friends there, even though I was a math major doing other things. When it finally came to pass that I got into graduate school, and I didn’t quite know what I wanted to do, it seemed to me that all this, economics and worldly things, would be useful. It was something I ought to think about doing, so I went back and I saw them. I didn’t go back and see my math professors. I went back and saw people like Ed Tufte, a political scientist and statistician, and he pointed me to a few people in Boston. And they pointed me to the Harvard Business School, saying that was a place that would take an itinerant mathematician with good credentials, who didn’t necessarily know anything about economics, and would let them learn on the job. And sure enough, I don’t quite know why they did, so they gave me a position teaching managerial economics, and I didn’t know a thing about managerial economics but neither did the students. I was okay, and I learned faster than they did so it worked out just fine.

In fact, I became an exceedingly popular teacher, and I just threw myself into the teaching and the work, but after a year or two, I realized that while I enjoyed the teaching tremendously, the research component — the sort of serious research that I had been doing — I still felt was missing in my life, and I had no clue what I wanted to do.

One summer I was finishing up a book, coming out of my thesis on a very abstract subject — algebraic combinatorics, for goodness sakes! — and I didn’t know what to do, so I spoke to my brother. My brother was a development neurobiologist and was going through graduate school, and Arthur suggested to me, “You’re a mathematician. You know all about information theory. You should learn about the brain. The brain is a really great place to apply it.” So being hopelessly naive, I said, “Okay, I’ll learn neurobiology this summer.” I got a couple of books and papers and things on mathematical aspects of neurobiology. They were interesting, but they didn’t ring very true, and I, in any case, decided I had to learn more neurobiology. So I started learning about neurobiology, wet lab neurobiology. I decided in order to do that I needed to know more biology, so I decided, okay, next semester I’d learn biology.

I sat in on a biology course. I took the laboratory component of it, freaking out the poor graduate student who has this business school professor sitting in on his course. But he was kind enough to take me back to his lab and introduce me to his own advisor, and Peter and Lucy Cherbas gave me a bench in their laboratory and taught me how to clone genes. So I moonlighted cloning genes in their lab for a couple of years, figuring that genetics was the most rigorous place to start, figuring I’d work my way back up to the brain. That’s how I became a biologist. I became a biologist very much through that suggestion of my brother’s, and through this lucky series of accidents, and stumbling upon people who were kind enough to take me, and then picking up biology on street corners — admittedly very good street corners — in Cambridge, Massachusetts. But largely, most of my biology education came while I was teaching as professor of managerial economics at Harvard Business School.

It’s never too late.

Eric Lander: It’s never too late. It leaves me singularly unqualified to advise my students on how they should run their careers, because they certainly think that this is a crazy way to do things, and I occasionally have to remind them that these crazy ways to do things are about the only ways that really in the end turn out satisfying.

It’s fun to read a brief bio of you, because for all the world it looks like it’s a typo. We go from, “Ph.D. in math, taught managerial economics at the Harvard Business School…”

Eric Lander: Then it switches to molecular biology.

“Oh! Obviously they made a mistake. That must be somebody else’s bio.” We’re glad to hear the story directly from you, because it finally makes sense.

Eric Lander: Well, as much as any of these do make sense.

We talked to John Gearhart recently. He started out studying apples and pears and ended up in gynecology. He had no idea he was going to be in stem cell tissue research. Is there a message there for kids?

Eric Lander: It’s a crucial message for kids. In my case, after I began to pick up biology, I still wasn’t really clear what I was going to do with it. I was despairing for several years of having thrown away a great career in mathematics. Not really pursuing this thing at the business school that I had, and learning biology, and what was I going to do with it?

I eventually talked the business school into letting me take a year’s leave of absence, and I went down to MIT to work with some geneticists working on the nematode worm, which is a very good model of genetics, and by chance, again, one Tuesday afternoon I met David Botstein. He was a yeast geneticist who had recently come up with a brilliant idea for how to do human genetics, but what he really was lacking was a mathematical quality, because it needed a lot of mathematics to really develop it. So David and I just hit it off. We started talking. He was from the Bronx, I was from Brooklyn. We were arguing in the halls, having a great time, and one thing led to another, and I dropped everything else I was doing and began to work intensely with David on these ideas about human genetics.

I got invited — David dragged me along — to an international meeting in Helsinki in ’85, and then he got me invited to speak at a famous meeting at Cold Spring Harbor in 1986. The meeting that year was on human genetics, and it is the scene of the famous debate on the Human Genome Project that took place. And there were all these highfalutin Nobel Laureates up on the stage expressing opinions, and then they turned to the audience, and even though I was tremendously inhibited and intimidated, I raised my hand anyway and sort of threw myself into the discussion. Remarkably, after the discussion, a couple of senior people came over and said, “Oh, do you want to come to dinner? We really liked some of the things you said,” and we were chatting. And a couple of weeks later I found myself invited to participate in some meeting on the Genome Project, and a couple of months after that I found myself invited to chair some subcommittees on the Genome Project, and I quickly realized that there were no experts on this subject, and I could pass for an expert on this and that was just fine. So all told I was still very worried about it. I asked Botstein, “What am I going to do to ever get a job in this?” I was still teaching in the business school at the time, while I was moonlighting doing all this, and I said, “I don’t look like a standard issue molecular biologist. Who’s ever going to give me a job?” David said, “You’ve got it all backwards. It’s the guys who look like standard issue molecular biologists who have a problem. They all look the same. You look different. Any place would be glad to have one of you. Maybe not two, but glad to have one of you.”

And he was so right, because…

The way it shook out, by 1988 or so, was here I had this training in genetics. I had training in mathematics that was turning out to be tremendously important for all this genome stuff. I had a background in business, from having taught at a business school, at a time that biology was organizing its first large scale project that required organizational thinking. And I had a bunch of experience from journalism writing, at a time when expressing what this project was about and formulating it was tremendously important. So I suddenly had a recipe for a whole bunch of skills here that fell together, and I’d love to take credit for having planned it that way, but it wasn’t that way at all. It was completely by accident. And I found, within a year or so after that, I had an offer of tenured positions teaching at both Harvard and MIT in biology. A year after that, I launched one of the first Human Genome Centers in the United States. A year or two after that, I helped co-found a biopharmaceutical firm, and onward like that, but it was very much an accident. Even as recently as two years ago, when I got elected to the National Academy of Sciences, around age 40 or so, I found myself rather surprised and stunned to be taken seriously at all this stuff. Because I still viewed myself — as I still sort of do view myself — as an accidental interloper in all this, who just stumbled upon this field, but a very lucky field to stumble upon, and some very wonderful people to guide me along the way.

Timing can play a big role in any career. In your case, it seems like the timing was unbelievable.

Eric Lander: Genomics didn’t exist at the time that I came down to MIT and met David Botstein. The few beginning seedlings were beginning to come up, and I found myself bumping into one of the people who knew a lot about it, and within 12 months of that point the Genome Project was breaking on the world scene. The timing couldn’t have been better. I had nothing whatsoever to do with the timing — it was dumb luck — but somehow managed to take the opportunity and run with it.

There were other changes happening just as you were becoming involved in biology. One change was the proliferation of computers in biology, and the whole concept of computational neurobiology. Twenty-five or 30 years ago that’s not how people did science.

Eric Lander: Fifteen years ago computers played no significant role in biology. Biology has only become a computational discipline primarily in the last decade or so. So the time that I was getting into it as a mathematician, I was reasonably convinced that what I had done in mathematics was utterly irrelevant, and would be utterly irrelevant in the biology I did. Now biological computation — bioinformatics — are becoming tremendously important areas, and it’s becoming very clear that a large portion of biology is going to start with the information first, to generate the hypotheses for the lab, and so the field will have undergone a dramatic transformation over this period. If I had sought really good advice when I was in school, no one would have told me to use mathematics as a way into biology. Luckily, I never sought any of that advice. It just sort of happened.

Do you have any sense of destiny at work in all this?

Eric Lander: No, not a chance. I don’t think it was a sense of destiny.

I think we construct our lives out of the pieces we have, and the only rules to go by are to surround yourself by wonderful people, by smart people, very decent people, and then, as the physicists say, wait for productive collisions to occur. If there are a large number of high energy collisions, then there’s a large subset of productive collisions. So if you put yourself in those environments, things happen. And you take the pieces you have, which have to be the pieces you love. I didn’t go into journalism with the idea that writing would turn out to be tremendously important to me as a scientist. I didn’t go into studying the brain and biology with any idea of where I’d end up. You take the pieces you love, and then you fashion a life out of it, rather than looking for the pieces to fit some particular mold.

That’s beautifully said. When you tell the story today there’s a lot of humor and a cheery spirit, but there must have been a point when you had doubts about this jagged journey. Were there any setbacks or self-doubts along the way?

Eric Lander: Oh, it was mostly setbacks and self-doubts.

I now tell the story with a smile because it’s all worked out just fine, and I look back and I laugh. But through all of these peregrinations, through different fields and random walks, I was very frequently depressed about all of it, and deeply worried about this. After all, world class math student, a Rhodes scholar, won thesis prizes in mathematics. I had a great career prospect to go ahead and do pure mathematics. I discarded all of that and I wasn’t sure what for, and I recriminated often about that. I worried deeply about it, that I would never really have a good position in a university, or doing anything else for that matter. So anybody who imagines that you make these transitions without tremendous agonizing is absolutely wrong. I tell the story with a laugh today, but certainly it’s a very painful thing to be searching around like that, and not knowing what you really want to do. Eventually, you make enough transitions that you realize that life is about making those transitions. I still doubt I made them very gracefully. I reckon I have a few more career changes left in me, and I don’t imagine I’m going to do them completely gracefully. I hope, for the sake of my wife and my kids, I do them more gracefully than the ones I’ve done up to now, and worry maybe a little bit less, but you take these seriously. You throw yourself into them and they matter a lot, and somehow there’s great internal turmoil as you reinvent yourself and find out what you really want to do. What you have to do is balance it with a lot of fun along the way, but I would certainly be wrong to say that the whole thing was easy. It certainly, I don’t think, looks easy in retrospect, and it certainly wasn’t easy. What I was very blessed by was wonderful people to do it with, and wonderful help.