Other writers we’ve talked to want to do all the research first, get it out of the way, and then start writing, but you like to stagger it.

Ernest J. Gaines: It was the best way that I thought I could do it, because once I was ready to write the book now, I was ready to write that book, and many of the books that I needed, I did not have. I didn’t know how to get them, and so I was making constant trips from San Francisco back to Louisiana, going to the library at LSU, or going to the library at Southern, or going to the State Library in Baton Rouge to get this information. So while I’m in San Francisco, I have to do something. So I’m writing, writing and writing.

What was your part-time job that you had?

Ernest J. Gaines: I worked for an insurance company as a mail clerk. I worked in the post office, and I worked as a printer’s helper. They call it a “printer’s devil.” I had to pick up type with a tweezer, some of the type was so small, and then set it up for printing. I did all those little things like that.

What do you say to your own students now, about writing and about how much time they need to put in, how hard they have to work?

Ernest J. Gaines: The first thing I tell my students when they ask me — well, anyone who asks me what do you say to an aspiring writer, I said, “I have six words of advice, and I have eight words of advice. The six words of advice are read, read, read, write, write, write, and the eight words of advice is read, read, read, read, write, write, write, write.” I said you have to read in order to be a writer. Oh, I have students who — I teach creative writing at the university there, advanced creative writing, and I have students who write a draft, and they think they need an agent already, and I tell them, “No. It doesn’t work that way.” I graduated in ’57 from San Francisco State, and I gave myself 10 years to prove that I could do it, and it was exactly what I — my first book was published seven years later in ’64. That would be Catherine Carmier, but hardly anybody read the book. I think 3,500 copies were printed, and 2,500 copies were sold. Then I went back to writing short stories, my Bloodline stories. I sent that to Dial, but my editor told me that he could not publish the stories by an unknown writer. I said, “But those stories will make me famous.” He said, “Well, you’re not famous yet. You have to get that novel out.” So I decided to write a novel for him, and the novel was published in 1967, Of Love and Dust, and it was from that book I began to get recognition by the critics and others.

Where did you get your love of literature and books? When did that come?

Ernest J. Gaines: My folks went to California during the war in the early ’40s, my mother and my stepfather, since there was no high school in the area that I could attend — the high schools were for whites only — when I graduated from the ninth grade. I went to the sixth grade on this plantation, and then I went to three extra years of school in a small town, the small town of New Roads, which was about ten miles from that plantation where I lived. Sometimes I got a ride, sometimes I had to hitchhike a ride. Sometimes I caught the bus to get to school and had to do the same thing to get back, because they had no school buses to take me there and back. When I graduated from the ninth grade — yeah, ninth grade — my folks sent for me to come to California to go to school, because there were no high schools for me in that parish, and there I ended up in the library, the public library, Andrew Carnegie Library there in Vallejo, California. Vallejo is about 30 miles northeast of San Francisco. We were living in Vallejo at that time, and it was there that I went to high school and also discovered the library there, their public library, and I started reading. There were no books there by or about blacks, but I read the books that were there. There were lots of books there, but none by and about blacks.

I fell in love with literature. I read plays. I read poetry. I read novels. I especially liked the 19th century Russian novelist, Turgenev, the stories of Tolstoy and Chekhov stories, and I read that. I began to read them because they — I suppose because the relationship between those landowners and their peasants, their serfs, were so much like — and not like — the ones that I had come from. Those serfs and those peasants could become, probably, landowners themselves, or they can improve themselves. Whereas, where I had come from, it was impossible. So I read those books. I liked reading those books.

I began to read French novels, without knowing the meaning of things, I was just reading for the storylines, for the characters. I discovered American writing as well about that time. Then after graduating from high school, I attended two years of junior college there in Vallejo. It was free, and I did not have money to go to a four-year college. So I enlisted in the Army.

When I was discharged from the Army, I enrolled at San Francisco State to study literature, and it was there that I really got seriously into the writing. I had some wonderful teachers there on the campus at that time who were writers as well, and they encouraged me to write, and I wrote short stories. At about that same time, they were organizing a literary group on the campus, and a little magazine called Transfer — Transfer magazine — and I had the very first short story published in Transfer, and I also had — in the next issue — a second story of mine was published in Transfer. I think the magazine came out — a little quarterly that came out. It must have been a quarterly. So I had two stories, and then I wrote another story. I was writing stories at that time, and these three I submitted to Stanford University, and I won a fellowship there to study. After graduating from San Francisco State, I submitted those stories to Stanford, and I won a fellowship at Stanford to study there (with) Wally Stegner, who was the founder and director of the program at Stanford.

He was a great writer himself.

Ernest J. Gaines: A great writer, and a wonderful, wonderful person.

What about your parents? Did they support your ambitions in literature?

Ernest J. Gaines: No, not in the beginning. I’m the first person, first male in the history of my family to go beyond high school, and what they wanted me to do was to become a teacher or become a business person or — I don’t know — but not a writer, because no one knew anything about writers or writing. So I was not encouraged by my mother or my stepfather to be a writer, but that’s all I wanted to do from the time I discovered the library and started reading all those books. So about a year after I’d been there in California, I tried to write a novel. Of course, it was a failure. I sent it to New York, and they sent it back, and then I burned it.

That didn’t stop you, that experience?

Ernest J. Gaines: That experience didn’t stop me, but I had to study. I was falling back in my grades in school because I was spending so much time trying to write a book. I wanted to impress… anyone. I wanted to impress my aunt, who was still alive in Louisiana, but of course I was unsuccessful in the beginning, and by the time I did start publishing, she had died.

How old were you when you visited a public library for the first time?

Ernest J. Gaines: I was 16 years old when I went to the library.

I gather that just as you weren’t allowed in high schools in your hometown, you weren’t allowed in the public libraries?

Ernest J. Gaines: I was not allowed in the public library in Louisiana, in the area where I lived. There were public libraries for African Americans in the cities, Baton Rouge and New Orleans or places like that, but they were not very big libraries. They were small, but a few books. But in the little town where I lived, there was no library there at all that I could attend. So my first experience in going to a library was in Vallejo, California, in 1949.

Do you remember the first time you stepped into the library?

Ernest J. Gaines: I used to like to hang around with my buddies in the evening, in the afternoon after school, until my stepfather came in one day from his trip in the Merchant Marine and told me I had to get off the block or else I was going to get myself in trouble, because the town where we lived was a Navy town, and a lot of sailors, a lot of bars, a lot of all kinds of things going on. He said, “You’ll get yourself in trouble if you stay there.” So I had three choices. I had the movies to go to, or the YMCA, or the library. I didn’t have any money for movies, so I couldn’t go to the movies. So I went to the YMCA, and I had hung around there, I suppose two or three weeks, until I got in a ring with a guy who knew how to box, and that guy really beat me up. So I went to the library. I was too embarrassed. It was too embarrassing an experience to stay there, because everyone had laughed at me. So I went to the library, and it was then that I really started reading, out of loneliness and out of being too embarrassed to go back to that YMCA.

You make an excellent point. Many people don’t realize how books can combat loneliness.

Ernest J. Gaines: Oh yeah. I had missed my folks. I had missed my brothers and my aunt and friends, and I just started reading books. I would always read books about rural life. That’s why I had mentioned the peasants and the serfs of mid-19th century Russia. Whenever I’d find a book that had something about rural life in it, I would read it, regardless of who had written it, or what country it came from.

You mentioned some authors you enjoyed. Were there particular books that had a big influence on you when you were starting out?

Ernest J. Gaines: I read Turgenev, Ivan Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons, and that book had a tremendous impact on me. It was about a young man who came back to the old village to visit the old people after he had graduated from his university, and he used to be a doctor, and falls in love with a beautiful woman and all that sort of thing. They lived out in the country. When I was writing my first novel, Catherine Carmier — I started writing it in ’58, I think, ’58, ’59 — I knew nothing about writing a novel, and I used that Fathers and Sons as sort of my Bible, my guide. My first novel was about a young man who had been away from the old place, and then returning, and falls in love with a beautiful girl, and he loses her. I was really very much impressed by — influenced by — Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons at that time, but then I started reading other books, of course. I was reading other books at the same time, but that was the book that had the earliest influence on my structure — structuring a novel. It was small, and it was tightly written. It was about the country and older people and a young educated man who was a nihilist. So I thought at that time I was a nihilist, too.

You’ve gone back to Louisiana so often in your books. One might think you would want to escape what you experienced and endured as a young person, but you keep returning through your fiction.

Ernest J. Gaines: Yeah. I’ve written seven books — eight with a children’s book, but the children’s book was one of the short stories — and my Bloodline stories. All of them have been about Louisiana. Although I lived in San Francisco during that time, all of the books have been about Louisiana. The body had gone to California to be educated, but the soul was still there in Louisiana, and it was only that place that I really wanted to write about, from the beginning and even to this day. Friends have suggested — and editors and publishers and agents too — that I should maybe write about something else, but I can’t. I know, yes, it was pretty hard, tough, living in the South as a small black child during that time, but I had a lot of fun too. There were some happy, happy days. We could fish. We could hunt. We played a lot. We could walk some distances without anybody caring about your walking across properties. We could collect the different fruit that grew in the fields and trees along the road. Those are some wonderful moments, and the people whom I loved the most, including my aunt, and many of the older people were still there.

Because my aunt could not travel, many of the old people used to visit her, come there and visit and talk all the time, really talked day and night. These people had never gone to school, so I’d write letters for them. I wrote their letters. I’d help create their letters, because they’d have two or three lines, and that was all they had to say, and then I’d have to help create the letters. So those are the kind of things that I wanted to put into my writing, about these people, and the younger people as well, my brothers and friends and the stories I’d heard. Some of them were very horrible stories, but some are wonderful stories, all of that. And I think the artist is very much — by the time he’s 15, 15-and-a-half — the direction which he’ll travel has already been established by that time. I don’t know how much you change after that, whether you’re a singer or a poet or a writer or a novelist. I mean a fiction writer or whatever. I don’t know how much you change after 15-and-a-half years, as far as your art is concerned.

In a work of yours, such as A Gathering of Old Men, the voice of the South is there. It’s almost like a transcription. You have such a tremendous ear for voices.

Ernest J. Gaines: I tried to write that novel from the first person point of view, and that was from the Lou Dimes point of view. Lou Dimes is Candy’s boyfriend, and he’s a newspaper guy, and I wanted someone like that, I thought, to tell the story. But then I realized after writing maybe six months or a year — well, I went through an entire draft, so it must have been more than a year — from his point of view, I realized that this book was not — I mean, his voice was not telling the story I wanted to tell. His voice could only tell what had happened, this guy had been killed, but he couldn’t tell it from the point of view of the characters, whose voices I wanted to hear, and that is why I chose to write the story over from that multiple point of view, starting out with an innocent little boy who does not know what is going on, and then gradually going to older people and people who knew what had happened and why it had happened.

We’ve read that you can almost hear these voices. I don’t mean in a parapsychological way, but just that you hear them in your imagination.

Ernest J. Gaines: Yeah. Right. Well, you know, I hate saying, “I hear voices.” I was interviewed in Fresno, California, about ten or 15 years ago, and the newspaper guy asked me how did I get my stories told. I said, “Well, I like writing from the first person point of view, but I have to get that voice down. I have to get that voice. I have to hear that voice.” So the next morning, I read the newspaper, and the newspaper headline was, “Writer Hears Voices.” So I thought that was not what I was telling him. I had to hear the voice of my characters, and that I had to concentrate so well on the area that I could distinguish one voice from the other.

I have about 15 different characters who speak, narrate in A Gathering of Old Men. I think there are 15 of them, and I had to get — some way I had to distinguish 15 different voices. I had to give each one of those voices different little characteristics, little nuances, each one needed to have, whether it was a small boy, Snookum, who was about — I suppose Snookum must be about eight years old or nine — to people who were 80 years old. I had several 80- or 70-year-old men in there. I have two educated white women, Candy as well as Miss Merle. How would I distinguish those two voices, difference in those two voices? I have a sheriff, a big sheriff in there. How’d I get his voice down? Then I have a little skinny deputy, his little deputy, I had to get his voice down. Then I had a minister who used a lot of religious terms, and another older lady who used a lot of religious terms. How do I distinguish those two voices? So I think it’s only through having lived in Louisiana and coming from such a place, because there we have so many different — we have several different dialects in my part of Louisiana. I come from Cajun, Creole, and of course both Creole black (and) Creole white there in Louisiana. I attended a Catholic school there for a little while. I knew the Baptist religion. My folks are Baptist. So you know, I draw from these experiences.

What impact did your teacher Wallace Stegner have on your decision to pursue a writing career?

Ernest J. Gaines: Well, I submitted the work, and he liked what I had done, and he gave me the scholarship to come there for a year. I was writing short stories. He is a wonderful critic, not only a writer himself, but just a wonderful critic and a wonderful teacher, and he saw one of my stories. He saw the three that I submitted to get to Stanford. Then he saw another one that was quite long. It must have been about 150 pages, I suppose, and he thought it was too long to be published as a short story, and not long enough for a novel, He edited it down, and I learned a lot from his editing. He also brought other potential writers into that classroom.

I was there with Ken Kesey, who wrote One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. I was in there with a fellow named Wendell Berry, who is from Kentucky, a wonderful writer, novelist and poet. I was there with a guy named Louis Haas; I think Louis was from Argentina. I was there with some guy named Waterhouse, and he was from England. So there were all of these people there, and we were all pretty much on the same level as writers go. Somebody had published maybe a little story somewhere, but we were all about the same level in the writing, and he (Wallace Stegner) worked with us all. We would have to meet. I think it was twice a week, and the rest of the time, he’d expect you to write. You know, at that time, I was writing eight hours a day. I had nothing else to do, other than meeting my class twice a week; I could write eight hours a day. So I was writing eight hours a day, he encouraged that. He wanted that.

Then he also wanted us to hang together. After leaving the class, he didn’t want us to just separate and go in different ways. He wanted you to sort of stay around Stanford. So we would go to a little bar and drink beer and talk and things like that. There was always a party going on, and he was giving parties or someone in the department giving a party. So we were always invited, and he was always there. He was always bringing critics there. Malcolm Cowley was there, and other critics came in.

Was it unusual at that time for a major university to have a writing program, with a major novelist leading it?

Ernest J. Gaines: With a major novelist, yeah, but there were people leading those programs at that time. Cal (Berkeley) had a famous critic over there at the time, and there was the Iowa writers workshop. There were programs.

We were speaking of your teacher, Wallace Stegner. I understand you were both on the short list for a Pulitzer in the same year.

Ernest J. Gaines: We were. That would be 1972, and both he and I knew that we were on the short list. He thought I was going to win it, and I thought I was going to win it, because a lot of people were telling me that Miss Jane Pittman has everything. And then, of course, I did not and Wally did, and I called him early that morning. I suppose he’d gotten many calls, and we talked, and I said, “Wally, you know, I thought I was going to win it.” He said, “Yes, I thought you were going to win it, too.” I said, “Well, if I didn’t get it, you know, you’re the man I wished got to receive that award.” He said, “Thanks, Ernie.”

What was his book that won?

Ernest J. Gaines: His book was Angle of Repose.

Did he communicate to you his pride in your being on that list?

Ernest J. Gaines: Oh yeah. He would always call, and I’d see him after I left Stanford. There were always parties going on in San Francisco. Someone was giving a party, someone was getting a book published, and he would show up, or something was going on down at Palo Alto at Stanford, and I would go down there. So he stayed in contact with his writers. I don’t know that he stayed in contact with all of them, because some of them got in trouble, but most of us came through pretty well.

Didn’t he ask you once who you were writing for?

Ernest J. Gaines: He asked me who was I writing for, and I said, “Well, Wally” — he wanted us to call him “Wally,” you know, because we were all informal around the place. He didn’t want anyone to call him “Mr. Stegner” or anything like that. I said, “Well, Wally, I don’t write for anybody in particular.” I said, “I’ve learned from many writers.” He said, “Well” — I said, “I’ve read all these writers.” I said, “I learned a lot from a writer like Ivan Turgenev,” but I said, “He was just an aristocrat writing in the 19th — mid 19th century — and I know he was not writing for an Ernie Gaines on a Louisiana plantation.” And I said, “Still, I learned from him because of the way he wrote that little novel. I learned about a young man coming back to the old place and how he reacted to the old place.” I said, “I didn’t know anything about that until I read that book,” and he said, “Listen, Ernie.” He said, “Suppose a gun was put at your head, and that same question was asked. Who do you write for?” I said, “Well, in that case, I’ll come up with an answer.” And I said, “The answer would be that, first, I’d write for the young black youth of the South, so that I could help him in some ways to find himself, his directions in life. Let him know something about where he’s coming from, what he came from, and how to try to help him find his way.” And then Wally said, “Well, suppose that gun was still at your head,” and I said, “Well, then I’d write for the white youth of the South, to let him know that unless he knows his neighbor for the last 350 years, he knows only half of his own history, that you have to know the people around you. And his neighbor, of course, was the blacks, African Americans.” So that was all the discussion on who I write for, but I don’t write for any particular group. When I face that wall, when I sit at that desk and face that wall to write, looking at the blank wall, I just try to create those characters as well as I possibly can create them.

Do you create them on a computer these days?

Ernest J. Gaines: I have a computer, but I still have to write longhand first. I have to feel the words. I have to feel what I’m doing, and then after I have written longhand, then I will go to the keyboard. All the books have been written on typewriters and not computers.

Longhand and then typewriters?

Ernest J. Gaines: Longhand. Longhand on a canary-color paper. I like writing on yellow paper because — it has to be a soft canary-color paper — and with ballpoint pens, several. I’d get a box of them around the place, and I’d get two or three reams of paper and start writing. And once I have done that, then I’d type it on the canary-color paper, and then I’d go over it, change things around if I have to, and then I’d go to the white paper, and then I send it to New York. So I’ve really gone over it about three times by the time I send it to my editor and my agent. I’ve gone over it three times already. And as I said earlier, I went over Catherine Carmier about six or eight times. I must have gone over it 18 times or more, 20 times or more.

I also read that you have a picture of Faulkner up in that room.

Ernest J. Gaines: I have a picture of Faulkner and Hemingway in my office at the university where I teach. Yeah. They’re right over the desk. I collected a lot of pictures back in my San Francisco days. I’d have pictures of writers and bullfighters and all kinds of things around the place, jazz musicians. But in my office at the University of Louisiana, Lafayette, I do have Faulkner and Hemingway there. Also, I have a picture of Martin Luther King, a picture of Cicely Tyson as Miss Jane Pittman, a picture of Booker T. Washington, all kind of pictures around that place, but yes, Faulkner and Hemingway are both there.

They keep you company? They don’t intimidate you?

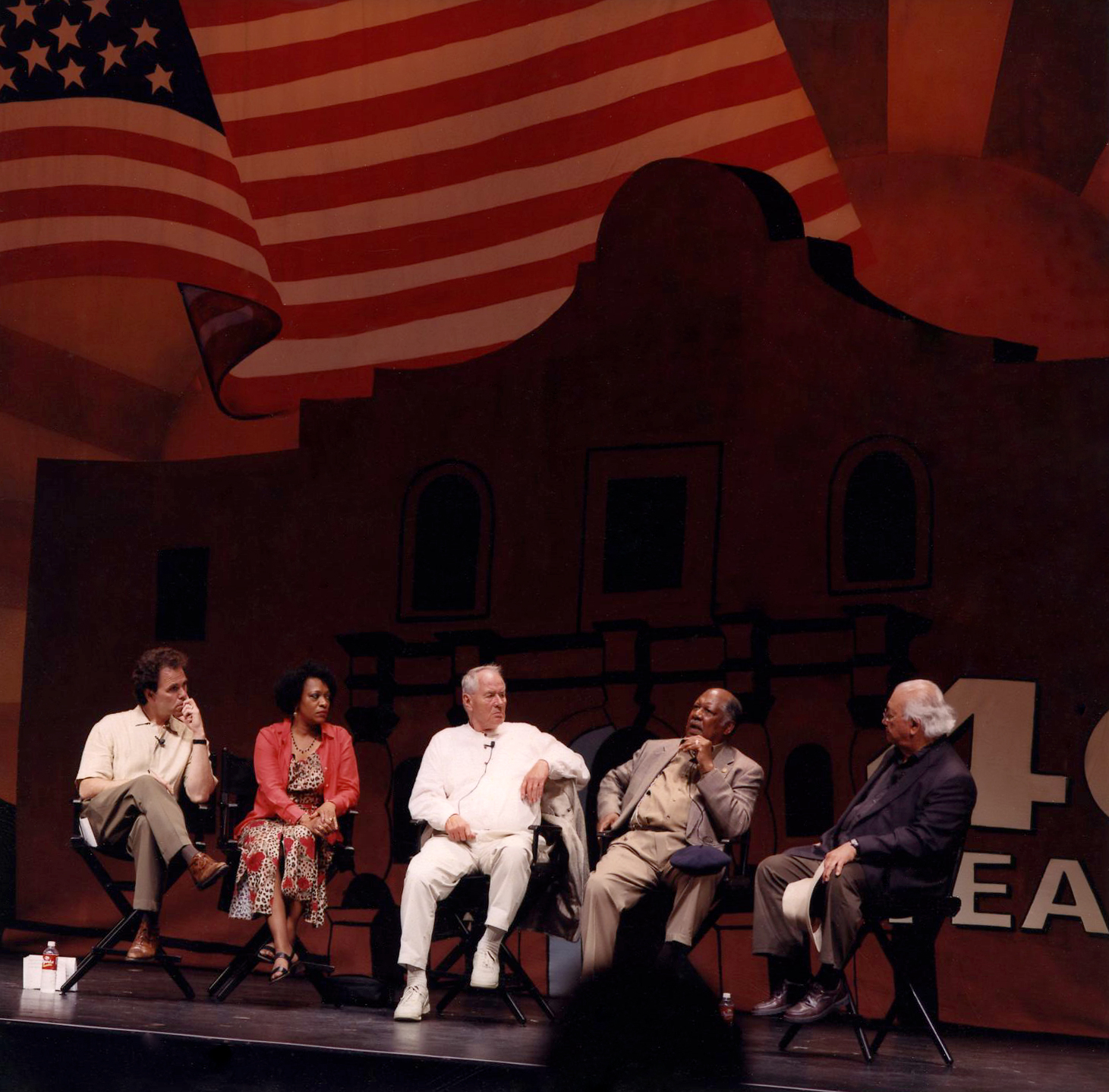

Ernest J. Gaines: No. Their picture can’t intimidate me. Maybe their writing can when I’m reading it. I see how well they could do certain things, how well Faulkner could do certain things, or Hemingway. So I’ve learned a lot from them. They’re like great uncles of mine. They may be intimidating, but you know, I can get along with them, because I think I know some things they don’t know. If they had lived beyond 60, they would be more intimidating, but so many things have happened. But I think Shakespeare and Tolstoy would have intimidated them, you know. So I feel that it’s just something like a baton that is being carried on. Shakespeare went so far, then he had to leave us, and then Tolstoy picks it up. He goes so far, and he had to leave us, and Faulkner goes so far, and we just keep going. I think it was Goethe who once said that “Everything has been done. The trouble is doing it again.” So we’re just doing it again. Someone mentioned last night on the panel that there are only two kinds of stories, a story about someone leaving and a story about someone coming in. They would have done the work had they been able to live. Shakespeare would have written everything that was necessary to write if he could have lived another 500 years, but since he did not, he could not, and someone had to write The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman. I did that. A Gathering of Old Men or A Lesson Before Dying, so I could do that, but we’re dealing with the same sort of old subjects, I suppose.

When you started getting recognition, was your routine still to write all morning and then stop for a while and then write more? Do you generally have a set routine?

Ernest J. Gaines: Yeah. I still do the same thing, because although I was getting recognition, I wasn’t getting any money. So I was going to have to work for a living. Well, I was getting some money. I got a Rockefeller grant, Guggenheims, I began to get some in. National Endowment for the Arts. I was getting some money, but not enough to support me. So I stuck to the routine of writing in the morning. I still like writing in the morning, start writing about 9:00 and go to — 9:00-to-2:00-type stuff — and working in the afternoon, I had to do it, but the last 25 years or, I suppose, 30 years now, I’ve been able to go to college and universities, given honorariums to come work. I’m teaching now, and I’m tenured at my university there in Louisiana now, but before I was tenured there, I would pick up little jobs at different universities. I went back to Stanford for a couple of quarters there, and several other universities where I would teach for two or three weeks, or whatever amount of time they would keep me there. So I’d make enough there for a while, about the routine of writing was always in the mornings. The teaching — the classes — were always in the afternoon, and the writing was always in the morning.

How did you first get the idea for the book A Lesson Before Dying?

Ernest J. Gaines: Living in San Francisco, I was living across the Bay from Marin County, and of course, Marin County is where the state executed the criminals in the State of California, at San Quentin. And whenever there was an execution, I would not write that day. I couldn’t work that day. I couldn’t do anything, or the day before, trying to imagine what this person was going through, and I would take off my watch and leave my watch. I’d go to the ocean and stay at the ocean the day of the execution. It was always 10 o’clock in the morning, and I would always just get away from everything, get away from people and go to the ocean. I could walk to the ocean, which was about four-and-a-half miles from my house, and I’d just stay there. I was always haunted by people being executed, for years and years. How do you feel about it? And I realized that in order to try to get rid of this, exorcise this, I had to try to write about it.

Whenever I heard about an execution, I’d read about it, but it’s hard to take. One of my favorite books about young people being executed was (Leonid) Andreyev’s The Seven Who Were Hanged, just a fantastic story. Andreyev was a Russian writer in the latter part of the 19th century. Because there were seven of them, I learned a lot about their habits, knowing that they were going to die on a certain morning, and I thought that maybe I could write a story somewhat like that.

A common theme in my writing, one of the things in my writing has been about someone teaching someone younger something about life. Miss Jane does the same thing, and in Of Love and Dust I did the same thing, and a short story called “Three Men,” we got the same thing. Someone is teaching somebody. Catherine Carmier. It was not always a teacher, but an older person, a much more wise person teaching a younger person about life, and I’ve always wondered in schools what were — what did we teach anyone? What did we teach people in school? Surely, when I went to school, I was taught reading and writing and arithmetic. The teacher — I only had one teacher in this classroom — and he could not have taught me anything about pride and about my race or history of Africa or whatever. He couldn’t teach me anything. He didn’t have time to teach anything other than the basic things: reading, writing, arithmetic. So I tried to combine the idea of teaching someone something and a young man who is innocent of a crime. I’d try to bring those two things together. And what does this young man owe the world — to the world — when he’s going to be executed for a crime he did not commit? What does he owe to the world? What does he owe to himself, when they think that he’s a piece of nothing? That’s all he’s been taught since a small child, growing up on a plantation, such as the one I created for that. He’s never been given love, except by his godmother.

But he learned nothing from going to school. He did not learn a thing in school, and this teacher who is teaching on this plantation at this time really hates his position there, hates the conditions which he’s teaching in. He’s a very bright person. He would like to do other things, run away, get away from there. Because at that time — this would be in the ’40s — it was limited to the things that a black could go into in a little place like that. He could be a storekeeper, or have a little night club, or he could be an undertaker or an embalmer or something like that, but he could not go into politics. He could not be an attorney. He could not vote. He could not be sitting on juries. He could not do anything. And he would like to get away, run, but he’s kept there by his aunt. His aunt makes such demands that he must stay around to help, to try to help the children in the school, and he does it. He does it very poorly until he has to go to this young man, Jefferson, on death row, and it was there that he tries to reach him, tries to teach him that, “You’ve gotten a rotten deal in this world. At the same time, you’ve got to be somebody. You’ve got to realize that you are somebody.” And he’s telling him this. At the same time, he still would like to run away. But as Jefferson began to come around — and it takes a long time, it doesn’t happen overnight — when he begins to come around and think that maybe he is somebody, this began to gradually work on the teacher himself, and it makes the teacher more humane toward others around him, toward his students, toward the older people around him, and toward his lady friend.

It’s a common theme I have that runs through so much of my work is that theme of commitment, of responsibility, that we are responsible for ourselves, regardless of whether we have four or five months to live, as Jefferson has before he’s to be executed, or someone like Grant who would have maybe 50 years more to live. What do you do with that time? What are you going to do for yourself, your family, your community? What do you do with your life during that time? So I was dealing with those kind of things. Of course, I have other characters running around the place, good ones and bad ones, to make the story realistic.

Speaking of those things, what does the American Dream mean to you?

Ernest J. Gaines: Oh, it’s probably just another cliché if I try to answer this in any way. I think that, to me, without love for my fellow man and respect for nature, that to me life is an obscenity. So that can be my feeling of the American Dream. Unless we care for one another and care for the world we live in, then it’s — what is the purpose of our life here? So I don’t know what the American Dream is supposed to be, but that all men should get along with all men, but, you know, that’s been said about a thousand times or a billion times.

You were picking potatoes at eight and you’ve lived to see such recognition, so many honors and awards.

Ernest J. Gaines: Yes, many. It’s me. I receive that, but what about my brother who did not receive that? What about all the others? I could probably name 50 guys my age — who would be my age now had they lived — who were destroyed in their 20s and their 30s and their 40s because of the world they lived in. Violence, death by gunshots or a knife or heart attacks or whatever, strokes because of the kind of stress they had to live under. They did not have my chance. So I’m only a chronicler. Who am I to write about some things, certain things? Yeah, I went from picking the potatoes and picking the cotton to winning all these awards and getting paid for my stories and my books I made, and the films and all that sort of thing, but I think about the others as well, the ones who never had a chance, and what I received just cannot possibly make up for what they’ve lost. It cannot possibly make up for it. And I realize that not all of us are going to have what I have, but how can we — how can the world — make it easier, so that these young men don’t wish for death at 20 and 30 years old, take any chance at 20 or 30 years old, or even their teens, because they don’t care, because they don’t see any future in their lives? If we can get a world like that, fix a world like that, make a world like that, then I think that would be the ideal American Dream, but I don’t know if that’s going to happen in our time.

How did you manage to write and do the research for your book A Lesson Before Dying? You said that in San Francisco, you couldn’t write on a day when you knew somebody was being executed across the Bay.

Ernest J. Gaines: No, I can’t. I just couldn’t think. I was numb. I had to get away. When I was doing research for A Lesson Before Dying, I met a fellow, an attorney there in Lafayette, and he described an execution to me. Up until 1952, execution in the State of Louisiana would take place in the parish in which the crime was committed — not at the State prison, as it is done today, with lethal injection. But at that time, the electric chair went from one place to another, one parish to another. And then it would be set up in the jail, in a little small room about the size of some closet, you know, just to put the chair in there, and the generator could be out on the truck, and run the wires through the window and connect it, and all that sort of thing. And the witnesses standing back and watching this stuff, not sitting or anything, but standing there and watching it. And this man told me this story. The case he’s talking about, the execution he’s talking about was in ’47, I think — ’46 or ’47 — and he must have told me that story in ’85, when I was doing research and working on A Lesson Before Dying. He told me that he could hear that sound of that generator for about two blocks away, and that so could the prisoner that’s right there, and everybody in that area within two blocks of the jail could hear this thing going on like this. And he just broke down, remembering this thing, so vividly remembering it. He broke down right there on my porch and started crying. A student of mine had brought him over there to talk to me, and she took him in her arms and just held him while he wept. I suppose this is the kind of feeling I had whenever these things were going on in San Quentin at that time.

You also said you were struck with the idea of knowing the hour of your death.

Ernest J. Gaines: Knowing the hour. To know exactly, when the guy tells you, 12 o’clock tomorrow, whatever time, and then to hear this motor thing out there, it’s…

What’s next for you as a writer? What are you working on now?

Ernest J. Gaines: It’s been a long time since I’ve written anything that’s publishable. My latest novel is seven years ago now, almost eight years ago. I have something in mind. It’s Louisiana again. I suppose by now, I could have written something about California. I’ve tried to write about California. I tried to write a ghost story. I tell people that it was so vivid that I scared myself, but that’s not really true. It was just bad stuff. I tried to write Bohemian life, about my Bohemian life in San Francisco, but I was not very good at that because I couldn’t take the sandwiches and the wine all the time. I’ve tried to write about my Army experience. I was stationed on Guam for a year, but I found that I was writing too much, or I was repeating Mr. Roberts or something like that. So I had to come back to Louisiana, and it’s been sort of difficult to get a novel about Louisiana, but I think I have something in mind now that might eventually turn into a novel. It’s about time. I know my agent is asking me, and some of my fans are asking me, and I know my editor is asking me, “When is the next one coming out?” I don’t know when. I should hope that within the next couple of years at least. That would be exactly ten years since A Lesson Before Dying came out, but A Lesson Before Dying came out ten years after A Gathering of Old Men. So maybe I’m one of these every-ten-years publishing writers. There was a time when I wrote four books in ten years, but now it’s much harder to do.

Do you think it hard for some writers to handle success?

Ernest J. Gaines: I don’t know. Someone was asking me the same thing today, “Why aren’t you writing?” I said I’m not writing because I’m at places like this. I do a lot of traveling now. When I was poor and nobody knew who I was, I had nothing but time to write. Now my books are out there and being taught in high schools, universities, colleges all over the country, and I’m always being invited to come to these places and talk to students, because they’re studying my books, and I go. When no one knew my name, I wrote, and now that they know my name, I’m visiting. So maybe that’s success. Maybe that’s what success does to some people.

We all look forward to your next novel. Thank you so much for this interview. It was really great talking to you.

Ernest J. Gaines: Thank you.