Your best idea or work is going to be attacked the most…So you have to really be courageous about your instincts and your ideas, because otherwise you'll just knuckle under and change it. And then things that might have been memorable will be lost.

The son of composer and musician Carmine Coppola, Francis was born in Detroit, Michigan but grew up in Queens, New York, where his family settled shortly after his birth. Coppola entered Hofstra University in 1955 to major in theater arts. He was elected president of the Green Wig, the university’s drama group, and the Kaleidoscopians, its musical comedy club. He then merged the two into the Spectrum Players. Under his leadership, the Spectrum staged a new production each week. Coppola won three D.H. Lawrence Awards for theatrical production and direction, and received a Beckerman Award for his outstanding contributions to the school’s theater arts division.

After earning his Bachelor’s degree in theater arts in 1959, he enrolled at UCLA for graduate work in film. While still at UCLA, Coppola worked as an all-purpose assistant to independent film producer Roger Corman on a variety of modestly budgeted films. Coppola then wrote an English-language version of a Russian science fiction movie, transforming it into a monster feature that American International released in 1963 as Battle Beyond the Sun. Impressed by the 24-year-old’s adaptability and perseverance, Corman made Coppola the dialogue director on The Tower of London, soundman for The Young Racers, and associate producer of The Terror.

While on location in Ireland for The Young Racers in 1962, Coppola proposed an idea that appealed to Corman’s passion for thrift. On a minuscule budget, Coppola directed in a period of just nine days, Dementia 13, his first feature from his own original screenplay. Somewhat superior to the run-of-the-mill exploitation films being turned out at that time, the film recouped its shoestring expenses and went on to become a minor cult film among the horror buffs. It was on the set of Dementia 13 that Coppola met Eleanor Neil, who would later become his wife.

After he won UCLA’s Samuel Goldwyn Award for the best screenplay written by a student, Seven Arts hired Coppola to adapt the late Carson McCullers’s novel Reflections in a Golden Eye as a vehicle for Marlon Brando (who was to star for Coppola later, in The Godfather and Apocalypse Now).

In 1966 Coppola completed his Master of Fine Arts degree at UCLA, and directed his second film, You’re a Big Boy Now, which earned a commercial release and critical acclaim. He then directed the motion picture adaptation of the Broadway musical Finian’s Rainbow, followed by another original work, The Rain People, grand prize winner at the 1970 San Sebastian International Film Festival.

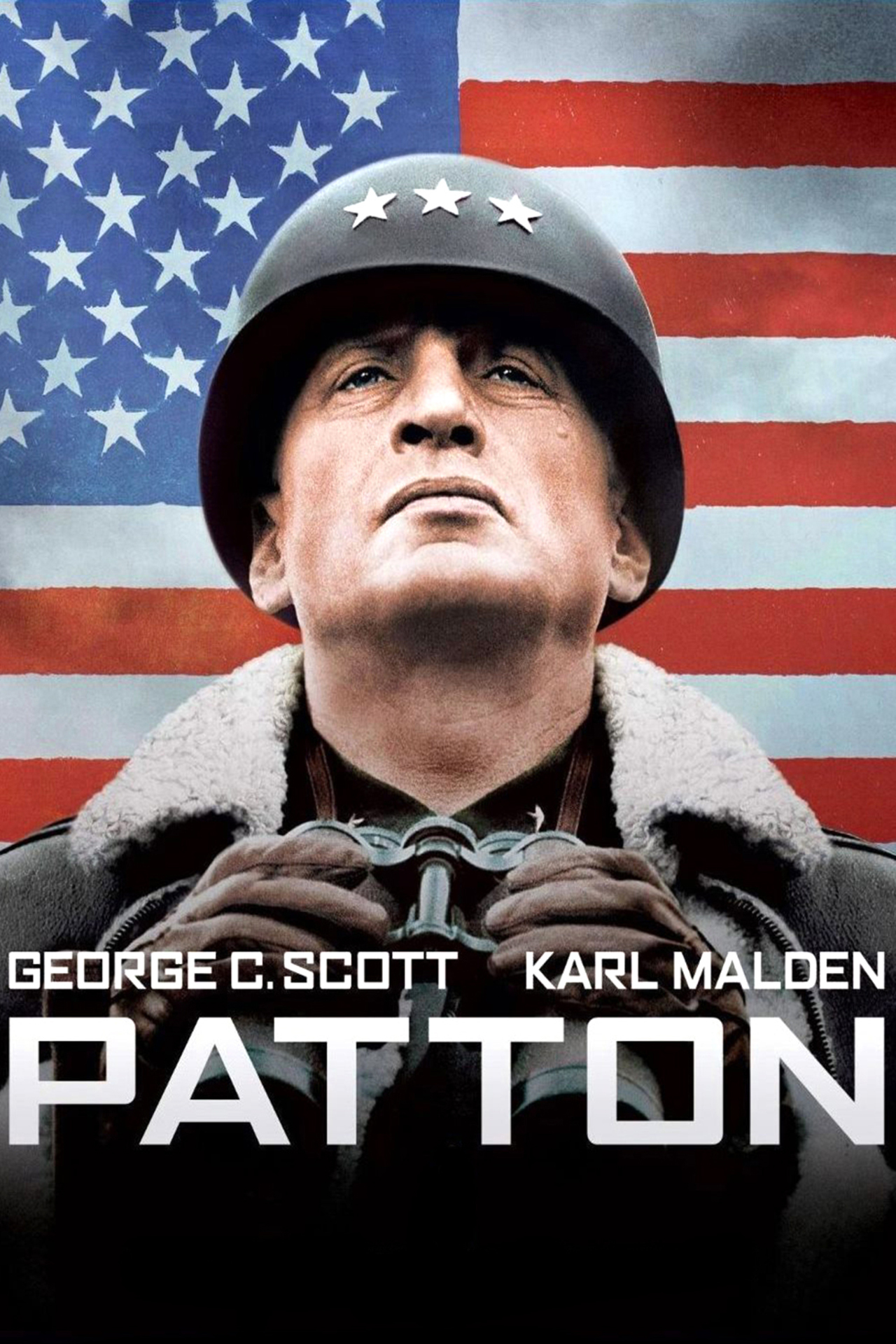

Coppola’s work on Reflections in a Golden Eye also led to a screenwriting assignment on the film Patton. Coppola shared the 1971 Oscar for best adapted screenplay with Patton co-writer Edmund H. North. During the next four years, Coppola was involved with further production work and script collaborations, including writing an adaptation of This Property Is Condemned by Tennessee Williams (with Fred Coe and Edith Sommer), and a screenplay for Is Paris Burning? (with Gore Vidal).

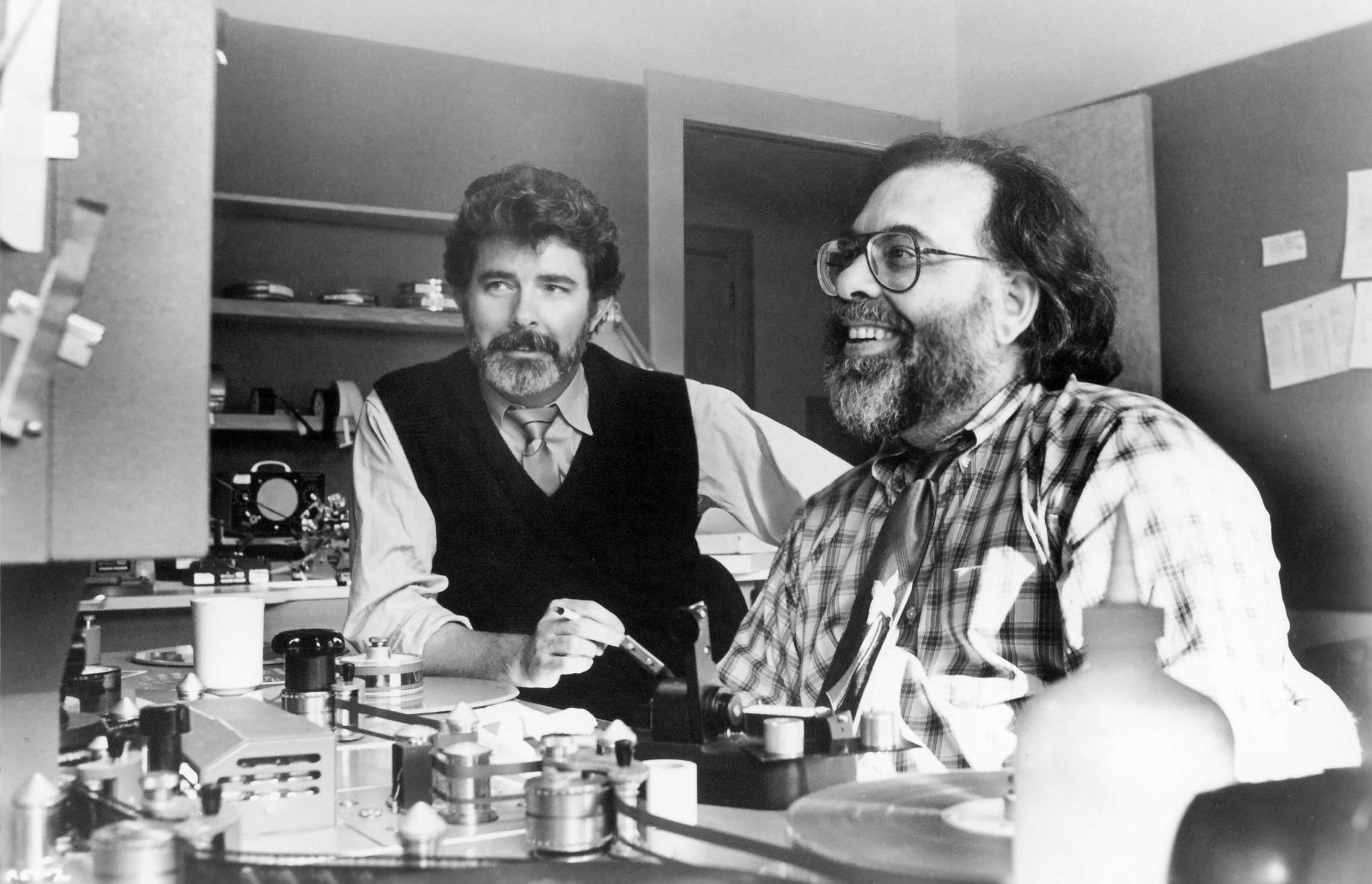

In 1969 Coppola and George Lucas established American Zoetrope, an independent film production company based in San Francisco. The establishment of American Zoetrope created opportunities for other filmmakers, including Lucas, John Milius, Carroll Ballard and John Korty.

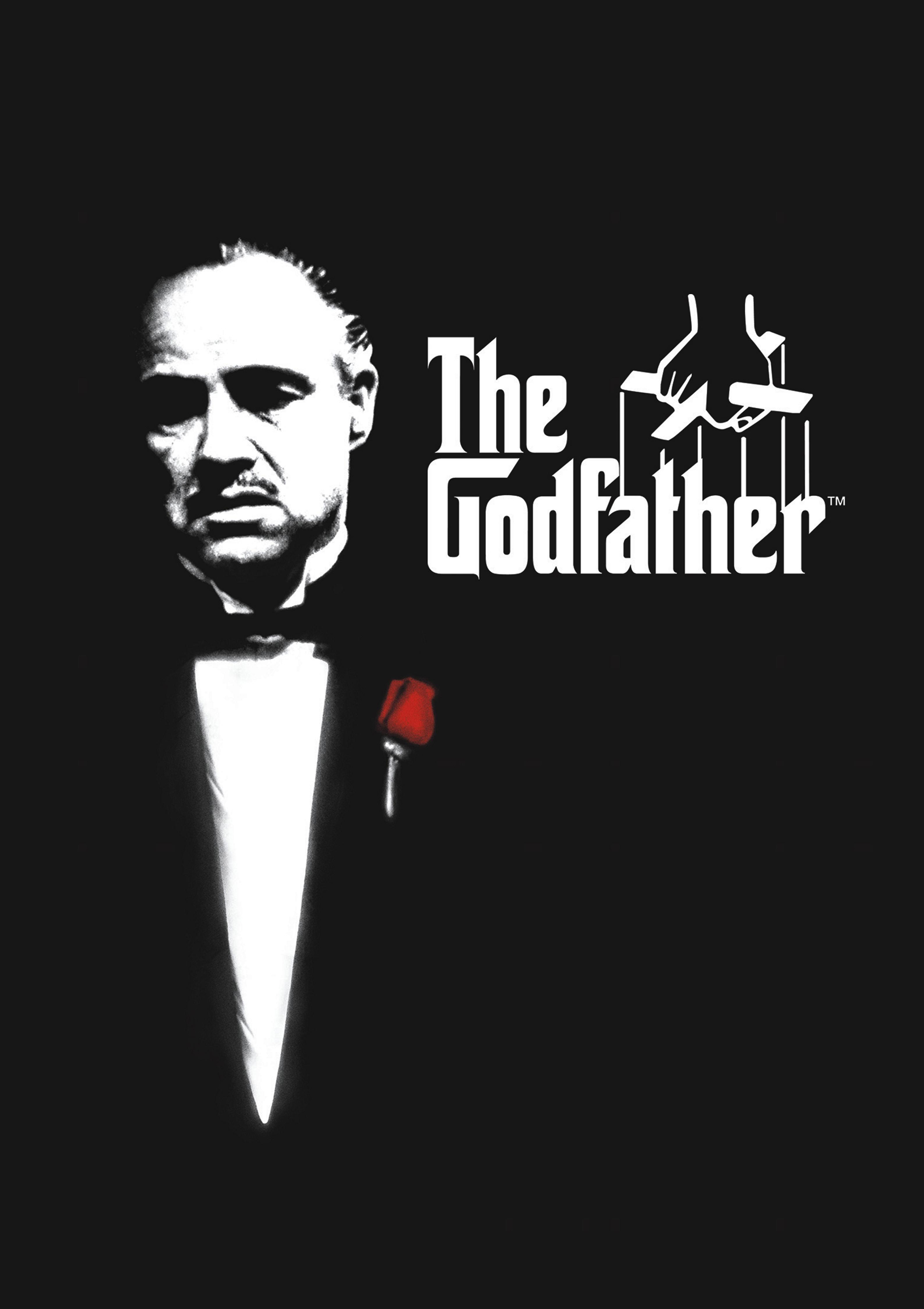

In 1971 Coppola’s film The Godfather became one of the highest-grossing movies in history, and brought him an Oscar for writing the screenplay with Mario Puzo. The film received an Academy Award for Best Picture and a Best Director nomination. Coppola’s next film, The Conversation, was honored with the Golden Palm Award at the Cannes Film Festival, and received Academy Award nominations for Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay. Also in 1974, Coppola wrote the screenplay for The Great Gatsby, and The Godfather, Part II was released. The Godfather, Part II rivaled its predecessor as a high-grosser at the box office and won six Academy Awards. Coppola won Oscars as the producer, director and writer. No sequel had ever been so honored. In all, Coppola had won six Oscars by the time he was 36.

At Zoetrope, Coppola produced THX-1138, and American Graffiti, directed by George Lucas. American Graffiti received five Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture. Meanwhile, Coppola had begun his most ambitious film, Apocalypse Now. The film was shot in the jungles of the Philippines over the course of a difficult year, chronicled in the documentary film Hearts of Darkness. This acclaimed movie won a Golden Palm Award from the Cannes Film Festival and two Academy Awards. Coppola was nominated for producer, director and writing Oscars.

Coppola’s idiosyncratic musical fantasy, One From the Heart, pioneered the use of video editing techniques which are standard practice in the film industry today. At the time, however, the picture made back less than $8 million of the $25 million Coppola spent producing it, most of which came from his own pocket. In 1983, Coppola was forced to sell his beloved Zoetrope Studio.

While some in the film industry predicted the end of Coppola’s career, he began his comeback immediately with a startling variety of films, many highly commercial, including the comedy Peggy Sue Got Married, the drama Gardens of Stone, and Tucker: The Man and His Dream, the real-life story of the maverick auto manufacturer Preston Tucker. The year 1990 saw the long-awaited release of The Godfather III. Although Coppola’s third film in the trilogy did not receive the critical acclaim or awards of its predecessors, it was a box office success, and Coppola’s professional vindication was complete.

![1990: Francis Ford Coppola directs Joe Mantegna (left), Al Pacino (center), Andy Garcia (standing right) and Eli Wallach (seated second from right) on the set of "The Godfather, Part III." [Paramount Pictures]](https://162.243.3.155/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/coppola-godfather226.jpg)

Coppola continued to direct successful films in the 1990s, including a remake of Dracula, but after shooting the acclaimed film version of John Grisham‘s The Rainmaker in 1997, he made no more films for a decade. Instead, he devoted his attention to a variety of business ventures, including a very successful winery, a restaurant — Café Zoetrope — in San Francisco, a mountain resort in the Central American nation of Belize, a production facility in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and a literary magazine, Zoetrope: All-Story.

After a decade away from the camera, Francis Ford Coppola returned to filmmaking in 2007 with Youth Without Youth, the idiosyncratic adaptation of a novel by the Romanian religious philosopher Mircia Eliade. Although the film pleased few critics, Coppola affirmed his intention to continue producing his own films independently, to avoid studio interference. His next project, Tetro, was an original story set in Argentina and shot at Coppola’s facility there. The film received mixed reviews but was a clear demonstration of Coppola’s determination to preserve his creative freedom. An experimental horror film, Twixt, shot on the grounds of his estate in Napa, California, also fared poorly with critics and audiences when it was released in 2012.

Undaunted, Francis Ford Coppola undertook his boldest and most innovative project to date, an unprecedented experiment in live cinema. Distant Vision is the multi-generational saga of an Italian-American family, winding through the early history of television. Experimental phases of the project have been conducted on sound stages at Oklahoma City Community College and at Coppola’s alma mater, UCLA. The epic production, which Coppola predicts will take five years to complete, employs multiple cameras to capture the story in continuous performance, to be streamed live in chapters to theaters around the world.

Francis Ford Coppola remains steadfastly dedicated to the cinematic arts. He sold his acclaimed winery in 2021 and invested an impressive $100 million from his personal funds into his new project, Megalopolis. This film, an adventurous mix of epic science fiction and romance, stands out as Coppola started writing its script 40 years ago.

Megalopolis signals Coppola’s return to the director’s chair after taking a break since his 2011 horror film Twixt. Premiering at Cannes in May 2024 with a stellar cast and otherworldly cinematography, Megalopolis was released in theaters in September, affirming Coppola’s enduring creative vision and legacy.

“They didn’t like the cast. They didn’t like the way I was shooting it. I was always on the verge of getting fired.”

Executives at Paramount had so little faith in the 32-year-old filmmaker they had hired to direct The Godfather, they actually hired another director to follow Francis Ford Coppola around the set, just to remind him he could be replaced at any moment. Despite studio interference, Coppola trusted his instincts, and The Godfather became a massive success with both critics and the public. Along with its even more acclaimed sequel, it is one of the highest-grossing films of all time, and appears on every list of the best films ever made.

Francis Ford Coppola has continued to trust his instincts, winning multiple Academy Awards forThe Godfather II, and directing such legendary films as The Conversation and Apocalypse Now. He has made and lost several fortunes over the course of a life as dramatic as his own films. Today, he is more productive than ever and, both by his personal example and his generous sponsorship of young filmmakers, has left an indelible mark on the history of motion pictures.

You were still a grad student at UCLA when you started working in the film industry. How did you get started?

I landed a job with Roger Corman. Originally the job was to take a Russian science fiction picture that he had bought and he wanted me to write the English dialogue for. Of course, I didn’t speak any Russian. Then I realized he didn’t care whether I could understand what they were really saying; he just wanted me to make up dialogue. The movie was really a very idealistic science fiction picture. He wanted to add some monsters and have the story be related to that. So I got that job, and I worked very hard on that. Ultimately, I became Roger’s assistant. That meant I had to wash his car, and he had me work as a dialogue director in the morning on a Vincent Price movie. Of course, they would pay my salary. But then I would leave at one and go work on his stuff. So he would basically get me for for free. The great thing about Roger was he exploited all of the young people who worked for him to the fullest, but at the same time, the other side of it was he really gave you responsibility and opportunity. So it was kind of a fair deal.

Tell us about the film you directed for Roger Corman.

Francis Ford Coppola: Roger had a technique. He would make a film, usually paid for by AIP, American International Pictures. He would put together the team and the equipment to make the film, and then, after it was over, he would make a second film, because all of those expenses were already paid. You’d get a real bargain on it.

Roger said he was going to make a film in Europe and asked me if I knew anyone who could be like the soundman on it. So I said, “Oh, I could.” Of course, I didn’t know anything about it. I mean, I was good with technology, but I had never done the sound. So I took the recorder home and read the instructions, and Roger did take me.

About three-quarters through that film, which was called The Young Racers, Roger was called back home to direct The Raven with Peter Lorre and Boris Karloff. I knew he couldn’t pass up a bargain to make another film while we were in Europe. So I said, “Roger, you know, I have a script that could be made. It’s kind of like Psycho.” He always wanted a film that was like some hit film. Hitchcock’s Psycho was a big deal at the time. I said, “I have this script…” and he said, “Show me some of it.”

I showed him the three pages I wrote that night, which was of course the most garish kind of action scene I could come up with. And he said, “Okay.” And I went off. He gave me a check for $20,000. He sent me with a young woman who had worked on the production who was going to be the co-signer — and I went to Ireland. When I was in Ireland, I met another producer, and I said I was making a film for Roger, and this guy offered to buy the English rights for another $20,000. So I had now $40,000. Roger, of course, expected to get his $20,000 back, still make the movie for the 20 with the English rights, and get the film for free. But I sort of just duped him. I took both checks and I put it in the bank. And I had this young woman sign the check, and I just kind of made the amount to the whole amount, so she basically was out of the check signing. Then I made the movie for $40,000, which was this little black-and-white horror film called Dementia 13, which we made in about nine days.

You wrote it in a couple of days?

Francis Ford Coppola: I wrote it that first week in Ireland. I had this one scene that I had showed Roger, and then I came up with the rest. I stayed up all night or something.

Which films really stand out in your memory?

Francis Ford Coppola: The professional world was much more unpleasant than I thought. I was always wishing I could get back that enthusiasm I had when I was doing shows at college. When I was young and it was new to me, it just seemed like so much fun. You didn’t want to go home at night, or you’d come back late at night and do some more work on it.

I always found the film world unpleasant. It’s all about the schedule, and never really flew for me in the way that my very happy college career did. I would have to say that the happiest days that I can remember were when The Godfather was over and I didn’t have to go there anymore, or when Apocalypse was over.

The Godfather was a very unappreciated movie when we were making it. They were very unhappy with it. They didn’t like the cast. They didn’t like the way I was shooting it. I was always on the verge of getting fired. So it was an extremely nightmarish experience. I had two little kids, and the third one was born during that. We lived in a little apartment, and I was basically frightened that they didn’t like it. They had as much as said that, so when it was all over I wasn’t at all confident that it was going to be successful, and that I’d ever get another job.

So I took a job right away when it was done. They needed someone to write a script of The Great Gatsby very quickly for the movie they were making. I took this job so I’d be sure to have some dough to support my family.

So I took a job right away when it was done. They needed someone to write a script of The Great Gatsby very quickly for the movie they were making. I took this job so I’d be sure to have some dough to support my family.

I went off, and I don’t know why I was in Paris, but I was in Paris, staying up all night writing this Gatsby script, and that’s when The Godfather opened. And it was this enormous success! So I would just get a phone call and they’d say, “Oh yeah, it’s going great! Everyone loved it!” I’d say, “Oh, yeah, really? I can’t get this script done.” It’s ironic that probably the greatest moment of my career, certainly at age 32 or so, making The Godfather, having such enormous success, wasn’t even one that I was aware of, because I was somewhere else and I was, again, under the deadline. Certainly, it was a wonderful night when we won all those Oscars for Godfather II, because at first, that picture came out, and people, they really didn’t like it too much. But I have to be honest, that I associate my motion picture career more with being unhappy, and being scared, or being troubled, or being under the gun, and not at all with anything pleasant.

What do you think are the most important characteristics for success in your field?

Francis Ford Coppola: Courage, I think, because I don’t think there’s any artist of any value who doesn’t doubt what they’re doing. That’s what I would say in looking back at my life, at the things that I got in the most trouble for, or that I was fired for.

I wrote the script of Patton. And the script was very controversial when I wrote it, because they thought it was so stylized. It was supposed to be like, sort of, you know, The Longest Day. And my script of Patton was — I was sort of interested in the reincarnation. And I had this very bizarre opening where he stands up in front of an American flag and gives this speech. Ultimately, I wasn’t fired, but I was fired, meaning that when the script was done, they said, “Okay, thank you very much,” and they went and hired another writer and that script was forgotten. And I remember very vividly this long, kind of being raked over the coals for this opening scene. My point is that what I’ve learned is that the stuff that I got in trouble for, the casting for The Godfather or the flag scene in Patton, was the stuff that was remembered, and was considered really the good work.

So, what that tells you is that…

In your own time, usually, the stuff that’s your best idea or work is going to be attacked the most. Firstly, probably because it’s new, or because they’d never seen an opening of a movie like that, or seen a gangster movie done in this style. So you have to really be courageous about your instincts and your ideas, because otherwise you’ll just knuckle under and change it. And then things that might have been memorable will be lost.

You need other things, obviously, a lot of energy and enthusiasm, because this kind of work is really grueling. You’re in a lot of uncomfortable situations for many, many hours. You try to stick to whatever your idea was, in a profession in which absolutely everybody is telling you their opinion, which is different.

The grips will tell you that you don’t know what you’re doing, or the camera operator, or the cameraman. Everybody. I mean, when you go on a set — that’s one of the reasons George Lucas never directed again. No one knows this, but when he made Star Wars over there in England — George is sort of a little, skinny version of me, you know, and he doesn’t have the most physical kind of stamina. And he was so ridiculed — you know, that kind of jock-like attitude that crews can have — putting him down for what he was doing and stuff. He was so unhappy making Star Wars that he just vowed he’d never do it again. Plus, he was like diabetic, so he was a little sick. That’s why someone today said, you ought to love what you’re doing because — especially in a movie — you really have to love the project and love the story, because over time you really will start to hate it. And the fact that you say, “Gee, but I really like what this is about,” is a very valuable asset.

Could you talk about the role of teamwork in your field?

Francis Ford Coppola: Our generation represented a major transition. It was the first time certainly that film students were given the chance to make films. Film, in the past, was a profession that you worked your way up. Frank Capra was a prop man; I think John Ford was a prop man. It was a little bit of a father and son thing, and you kind of worked your way up. When we all went to film school, my class, and my comrades there, we didn’t think we were ever going to really get to make feature films. We thought we would end up making industrial films, or possibly be on the fringe, or maybe get involved in television. My aspirations when I went — I had no idea. I just wanted to be part of the film business. I had no idea that I’d really get to direct feature films, or to be successful at it. And of course, my story is that when I was going for my graduate degree, I decided I was going to make a feature film as my thesis. That’s what I was famous for, was that I was not only the first film student to kind of become a professional director, but I also had my thesis film be a feature film, which was You’re a Big Boy Now.

So I was the first one to break in. I always loved the theater-like feeling of working together. That’s ultimately what I was trying to achieve in my life, because I had been a kid that moved so much, I didn’t have a lot of friends. Theater really represented that kind of camaraderie.

So a lot of younger would-be film directors started to come and hang out, because I had an office at Warner Brothers. I had directed Finian’s Rainbow when I was like 23 or something, and pretty soon all these kids — some of them my age, some of them a little younger — started hanging out with me. I had a little money, and I had a lot of ambition to set up a group, a company. So that’s when I met George Lucas, of course, who was younger, and then he had all his friends. Ultimately, it became kind of this gang of young filmmakers who really were friends and hung around together. The key thing about film students at that point is we all wanted to work in 35 millimeter. Film students were junkies for equipment. So suddenly I had penetrated the Hollywood studio, and due to very funny circumstances, which is that the company I was with, which was Seven Arts, had bought Warner Brothers. So for a while, no one knew who was running it, so I sort of had the keys of the whole studio, as though we suddenly had Warner Brothers. And we walked around and talked about, “We’re going to get animation going again.” Before I know it, there were all these guys coming there, and we’d talk about it, and that’s when I met people like Carroll Ballard, and George Lucas, and John Milius, and Phil Kaufman, I remember, and Brian Da Palma, and later, Marty Scorsese. They were all like a few years younger. Then we really decided we were going to be independent, we were all going to move to San Francisco, and we did. And that company produced some of those people’s first films, George’s films and what have you. I had always wanted to be part of that type of artistic scene like you hear about in Paris. What might have it been like to be there? There’s Hemingway in the Ritz Bar, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, or Sartre, and these wonderful people. When we were there (in San Francisco), broke, trying to figure out how to pay for anything, little did I realize that in effect, that’s what that was. That all those people were to go on and become wonderful artists and stuff. But then, it seemed like we were just a bunch of young people who wanted to take over the movie business. And in a way we did, but in a way we didn’t, because we really wanted better things for it than what really happened.