There's a range of creativity possible, and I think it behooves us to explore that envelope and push at it.

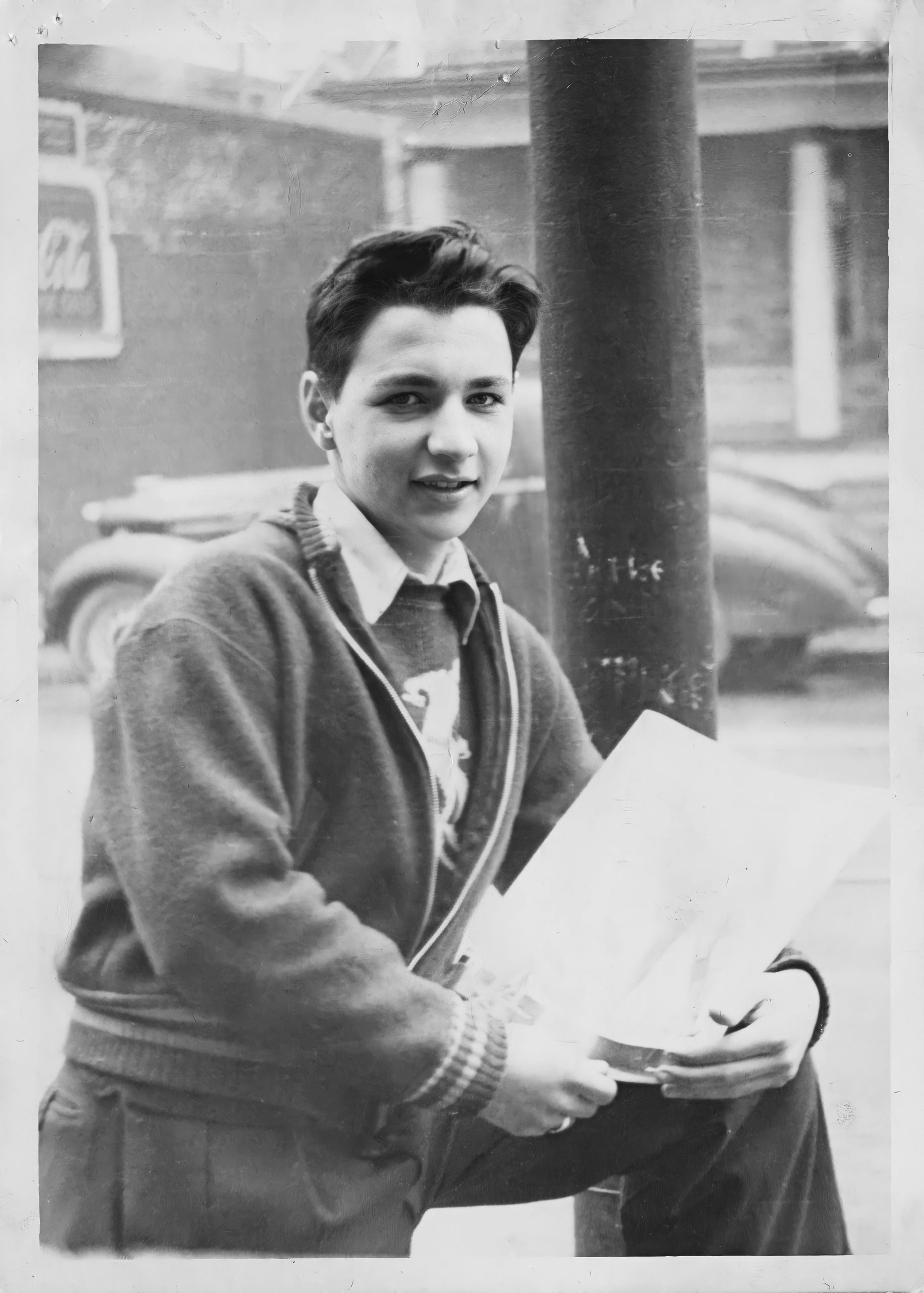

Frank Gehry was born Ephraim Owen Goldberg in Toronto, Canada. He moved with his family to Los Angeles as a teenager in 1947 and later became a naturalized U.S. citizen. His father changed the family’s name to Gehry when the family immigrated. Ephraim adopted the first name Frank in his 20s; since then he has signed his name Frank O. Gehry.

Uncertain of his career direction, the teenage Gehry drove a delivery truck to support himself while taking a variety of courses at Los Angeles City College. He took his first architecture courses on a hunch, and became enthralled with the possibilities of the art, although at first he found himself hampered by his relative lack of skill as a draftsman. Sympathetic teachers and an early encounter with modernist architect Raphael Soriano confirmed his career choice. He won scholarships to the University of Southern California and graduated in 1954 with a degree in architecture.

Los Angeles was in the middle of a post-war housing boom, and the work of pioneering modernists like Richard Neutra and Rudolph Schindler were an exciting part of the city’s architectural scene. Gehry went to work full-time for the notable Los Angeles firm of Victor Gruen Associates, where he had apprenticed as a student, but his work at Gruen was soon interrupted by compulsory military service. After serving for a year in the United States Army, Gehry entered the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where he studied city planning, but he returned to Los Angeles without completing a graduate degree. He briefly joined the firm of Pereira and Luckman before returning to Victor Gruen. Gruen Associates were highly successful practitioners of the severe utilitarian style of the period, but Gehry was restless. He took his wife and two children to Paris, where he spent a year working in the office of the French architect Andre Remondet and studied firsthand the work of the pioneer modernist Le Corbusier.

Gehry and his family returned to Los Angeles in 1962, and he established his own firm, Gehry Associates, now known as Gehry Partners, LLP. For a number of years, he continued to work in the established International Style, initiated by Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus, but he was increasingly drawn to the avant-garde arts scene growing up around the beach communities of Venice and Santa Monica. He spent more of his time in the company of sculptors and painters like Ed Kienholz, Bob Irwin, Ed Moses and Ed Ruscha, who were finding new uses for the overlooked by-products of industrial civilization. Frank Gehry began to look for an opportunity to express a more personal vision in his own work.

He had his first brush with national attention when some furniture he had built from industrial corrugated cardboard experienced a sudden popularity. The line of furniture, called Easy Edges, was featured in national magazine spreads, and the Los Angeles architect experienced an unexpected notoriety. Although Gehry built imaginative houses for a number of artist friends, including Ruscha, in the 1970s, for most of the decade his larger works were distinguished but relatively conventional buildings such as the Rouse Company headquarters in Columbia, Maryland, and the Santa Monica Place shopping mall.

Gehry found a creative outlet in rebuilding his own home, converting what he called “a dumb little house with charm” into a showplace for a radically new style of domestic building. He took common, unlovely elements of American homebuilding, such as chain link fencing, corrugated aluminum and unfinished plywood, and used them as flamboyant expressive elements, while stripping the interior walls of the house to reveal the structural elements. His Santa Monica neighbors were scandalized, but Gehry’s house attracted serious critical attention, and he began to employ more imaginative elements in his commercial work. A series of public structures in and around Los Angeles marked his evolution away from orthodox modernist practice, including the Frances Goldwyn Branch Library in Hollywood, the California Aerospace Museum and the Loyola University Law School. A number of his works in this period featured the unusual decorative motif of a Formica fish, and he designed a number of lamps and other objects in the form of snakes and fishes.

By the mid-’80s, his work had attracted international attention, and he was commissioned to build the Vitra furniture factory in Basel, Switzerland, as well as the Vitra Design Museum in Weil-am-Rhein, Germany. These projects established him as a major presence on the international architecture scene. His buildings displayed a penchant for whimsy and playfulness previously unknown in serious architecture. Most distinctive of all was his ability to explode familiar geometric volumes and reassemble them in original new forms of unprecedented complexity, a practice the critics dubbed “deconstructivism.” His international reputation was confirmed when he received the 1989 Pritzker Prize, the world’s most prestigious architecture award.

Although he originally completed his design for the proposed Walt Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles in 1989, funding shortages and political infighting delayed construction of the project for many years. The Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota, completed in 1990, was to be Gehry’s first monumental work in his own country, a billowing fantasy in brick and stainless steel. Meanwhile, his interest in collaboration with other artists was expressed in the fanciful design for the West Coast headquarters of the advertising firm Chiat Day, in Venice, California. The entrance to the building took the form of a pair of giant binoculars, created by the sculptors Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen.

Although his main project for Los Angeles went unbuilt through the ‘90s, he completed major projects in a number of other countries. His playful side reappeared in the “Dancing House” in the Czech capital, Prague. Comprising two undulating cylinders on a corner facing the river Vltava, the Czechs nicknamed the building “Fred and Ginger.” His proposal for a museum in Seoul, South Korea, which he discusses in his 1995 interview with the Academy of Achievement, was ultimately rejected, but an even more ambitious undertaking lay just ahead.

Gehry’s most spectacular design of the 1990s was that of the new Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, completed in 1997. Gehry first envisioned its form, like all his works, through a simple freestyle hand sketch, but breakthroughs in computer software had enabled him to build in increasingly eccentric shapes, sweeping irregular curves that were the antithesis of the severely rectilinear International Style. Traditional modernists criticized the work as arbitrary, or gratuitously eccentric, but distinguished former exponents of the International Style, such as the late Philip Johnson, championed his work, and Gehry became the most visible of an elite cohort of highly publicized “starchitects.” He drew fire again with his design for the Experience Music Project Museum in Seattle, but in his adopted hometown of Los Angeles, a long-delayed project was reaching fruition.

The year 2004 saw the long-awaited completion of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles. The building opened to great public celebration and immediately became the sprawling city’s landmark building. Although built after his Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the design actually predated it and featured a similar panoply of exploding titanium. The splayed pipes of the hall’s massive pipe organ were likened by more than one writer to a packet of French fries, but the public response was ecstatic. Gehry’s earlier experience building and renovating concert halls and amphitheaters had paid off in a facility that not only attracted international attention with its striking appearance, but thrilled musicians and listeners with its acoustically brilliant interior.

Over the years, Gehry has lent his imaginative designs to a number of products outside the field of architecture, including the Wyborovka Vodka bottle, a wristwatch for Fossil, jewelry for Tiffany & Co. and the World Cup of Hockey trophy. In 2006, the architect and his work were the subject of a feature-length documentary film, Sketches of Frank Gehry, by director Sydney Pollack.

In the following years, Gehry immersed himself in a number of projects, including the Barclays Center sports arena in Brooklyn, New York, a concert hall for the New World Symphony in Miami Beach, and another branch of the Guggenheim Museum in Abu Dhabi. Most ambitious of all is the massive Grand Street project, a plan to entirely remake the thoroughfare leading from Los Angeles City Hall to Disney Hall. When it is completed, a wide swath of downtown Los Angeles will bear the indelible stamp of its adopted son, Frank Gehry, and his restless imagination. In 2010, Vanity Fair magazine polled 52 of the world’s best-known architects and architectural critics, asking them to name the most significant works of architecture of the last 30 years. By an overwhelming margin, they placed Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao at the top of the list.

In 2014, the architect, age 85, completed one of his most dramatic structures yet: the billowing glass and steel Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, France. The project was built as a center for contemporary art and culture, and to house the rapidly growing art collection of the charitable arm of the French luxury-goods company LVMH Moët Hennessy-Louis Vuitton. The 126,000-square-foot, 2.5-story building is sunk slightly below ground level to comply with the height limits of Paris’s main park, the Bois de Boulogne.

The building’s glass and steel exterior framework, which Gehry calls the Verrière, was inspired in part by photographs of a greenhouse that had formerly stood on the site. The interior, which Gehry terms “the iceberg,” is formed by an array of white concrete cubes, supplying ample neutral space for the exhibition of art. The interior employs water in the form of a moat and a waterfall to reflect the ample light that floods all connecting areas of the structure. Located among the fields and trees of the Jardin d’Acclimatation, the historic children’s playground of the Bois de Boulogne, the Fondation Louis Vuitton may soon become the newest beloved landmark of the City of Light.

In 2016, Frank Gehry’s accomplishments were honored by President Barack Obama with the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The presidential awards citation, read in part, “never limited by conventional materials, styles, or processes, Frank Gehry’s bold and thoughtful structures demonstrate architecture’s power to induce wonder and revitalize communities.” It continues, “From his pioneering use of technology to the dozens of awe-inspiring sights that bear his signature style, to his public service as a citizen artist through his work with Turnaround Arts, Frank Gehry has proven himself an exemplar of American innovation.”

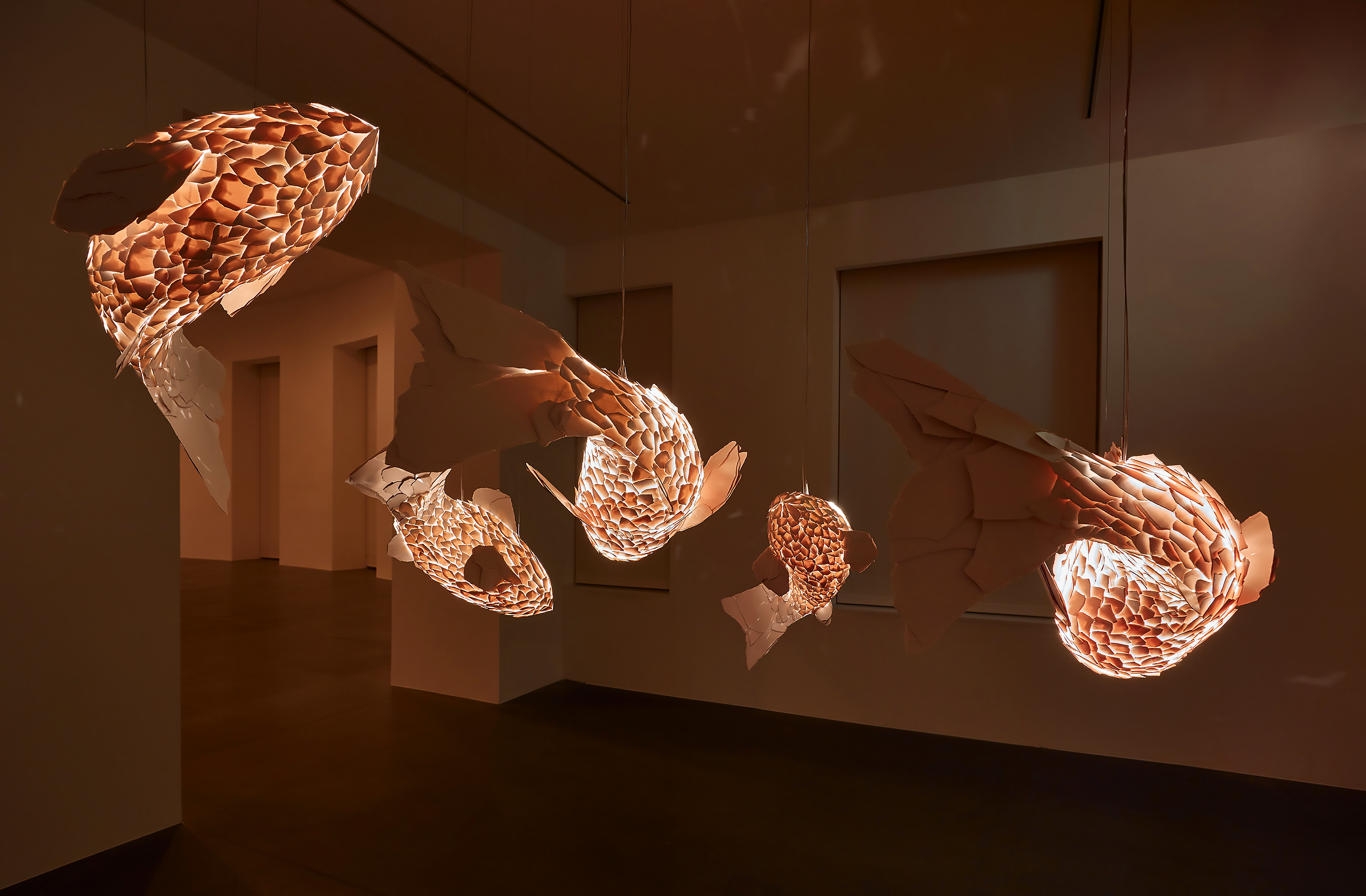

In his 90s, Frank Gehry’s creativity continued to extend beyond architecture. He designed sets for a jazz opera Iphigenia, by Wayne Shorter and Esperanza Spalding, created a fanciful design for the 150th-anniversary commemorative bottle of Hennessy XO cognac, and opened a new exhibition of his whimsical sculpture, including an Alice in Wonderland tea party and a vertically suspended array of his giant “fish lamps.”

Meanwhile, Gehry was still hard at work with an army of partners, collaborators, and assistants, completing a dazzling assortment of projects across the United States and around the world: a headquarters for the media and Internet holding company IAC in New York City, a renovation and expansion of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, a building for the New World Symphony in Miami and a memorial to President Dwight D. Eisenhower in Washington, D.C. He created twin towers for the King Street development in his birthplace of Toronto, designed a museum of medicine in Taiwan, and created the Luma Arles, a new arts complex in the South of France. After a long interruption, work resumed on the Guggenheim Museum project in Abu Dhabi.

Gehry’s influence is most pervasive in his adopted hometown of Los Angeles and neighboring communities, where he and his firm have undertaken projects such as new office buildings for Warner Bros. in Burbank, a hotel complex in Santa Monica, and new buildings for the Grand Avenue development in downtown Los Angeles. In a still more dramatic creation, Gehry projects construction of a green park and cultural center to be built on a massive platform bridging the Los Angeles River in Southeast Los Angeles. The SELA Cultural Center and park are envisioned as the signature structures of a long-term project to restore and revitalize the 50-mile channel.

He co-founded Turnaround Arts: California, a nonprofit that promotes arts education in the state’s poorest school districts. He transformed an old bank building in the South Los Angeles community of Inglewood to create a new home for the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s youth orchestra (YOLA), and has designed housing for homeless veterans in West Los Angeles. As the world’s great cities add buildings by Frank Gehry to their lists of historic sites and monuments, Gehry himself speaks most passionately of the projects that serve the communities in his own backyard.

Frank Gehry died on December 5, 2025, at his home in Santa Monica, California, at the age of 96. To the end of his life, he remained fully engaged in ambitious projects in Los Angeles, Beverly Hills, and Paris, continuing the inventive spirit that defined his long career.

When the other products of a culture have faded from human memory, it is the works of architecture that remain to define an era for successive generations. As the 20th century gave way to the 21st, it was hard to dispute that the definitive architect of the age was Frank Gehry, Canadian by birth, a resident of Los Angeles by choice.

He first drew notice in his adopted city with works deploying commonplace industrial materials in unexpected ways, but he came to international prominence with works which exploded the geometry of traditional architecture to create a dramatic new form of expression. He deployed cutting-edge computer technology to realize shapes and forms of hitherto unimaginable complexity, such as the startling irregularities of his Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, or the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles. In these monumental buildings, the uninhibited whimsy of his pencil sketches took shape in powerful structures of gleaming titanium.

From Switzerland to Japan, from Santa Monica to Prague, his buildings have transformed human expectations of the designed space. Once mocked for their astonishing originality, his buildings have become the signature structures of the challenging times we live in.

You’re famous for achieving a sense of movement in architecture, with complex curving shapes. What led you to this concept?

If you recall, Arthur Drexler did a big show of the past of great buildings, 19th century. He did a show at the Modern and it was stunning, and everybody at that time was sort of looking for an alternative to modernism, which was cold and inhuman, and they wondered how do we get out of this. And there Arthur presented them with the way out is to go back, and that was called postmodernism, and Philip did the AT&T — Philip Johnson. And then everybody jumped on it. And I remember being in a lecture somewhere or in a conference somewhere, and they were all talking about how wonderful the new architecture was and I objected. I said that the postmodern work came from Greek temples. Greek temples were anthropomorphic. And I said, “If you have to go back, you can go 300 million years before man to fish.”

And I just said that. Because I was looking for a way to express movement with architecture, because I couldn’t do decoration that was postmodern. I was looking for something to replace the feeling in a building. And I think so much of that came from looking at the Greek statues. If you look at the Elgin Marbles, those warriors are pressing the shields into the stone, and you feel the pressure, and you feel the horses are moving, and if they could do that with inert materials, I thought, “Why not see if that could become an architectural direction that would enliven the buildings, humanize them, and create humanity?”

Because very primitive is “the fold,” which there have been books written about it, Leibniz and people like that. Michelangelo spent years drawing the fold. And so you know the reason is when you’re a baby, you’re in your mother’s arms and you’re in the fold. And there’s something primitive, beautiful, and humanity about it. And I thought the Greeks knew how to express it. Can we do that in architecture?

I then started to sketch fish. Then I went back to my roots of architecture, which was Japan and I looked at Hiroshige’s wood cuts, and the beautiful fish drawings and how they were very architectural and expressive. I started to look in the koi pond and realized that there was something there to look at, emulate, and try to play with. Formica asked me to do something and I made a fish lamp. That was the beginning of it because the Formica was translucent and we put a light behind it. It was beautiful. So, and that led to a fish lamp, which Gagosian Gallery took on for some reason at that time and sold a bunch of them, and it still represents us and fish lamps. So we’ve tried to take them somewhere and do other things with them, but it’s something that seems to continue.

I made a fish for a fashion show at the Pitti Palace. And the fashion show was a company that billed Valentino, and I forget the names, all the great fashion designers. And I made this wooden fish 35 feet long. And inside the fish was a mannequin dressed in a beautiful new garb sitting on a chair and you could see it through the eyeball. And then some mannequins standing beside. And it was embarrassing, because the wood was very kitsch. The tails were there. The eyes were there. I didn’t have much time because I had to do this mostly over drawings sent and stuff. I had Cinecittà make the fish, and it was very quick.

When I saw the fish in — they took it to the — in Torino to the museum that started there. I can’t remember the name. But there’s an old castle. They turned it into a museum, and they had a show and they put that fish there along with some of my other models in a room. And I walked in and saw this kitsch piece of wood with — I mean it really was — I mean it was so embarrassing. I mean, “Oy oy oy!” And I remember standing beside it with the director of the museum at that time, a contemporary guy, a very famous guy — I forget his name — who was not a fan of my work, or he wasn’t into architecture. But I sort of represented maverick stuff. I remember standing beside him and I noticed that the fish moved. It seemed to move. And I didn’t say anything. He said to me, “Hey, can we have a drink?” Sure. I went down to the restaurant and had a drink. He said, “How’d you do that?”

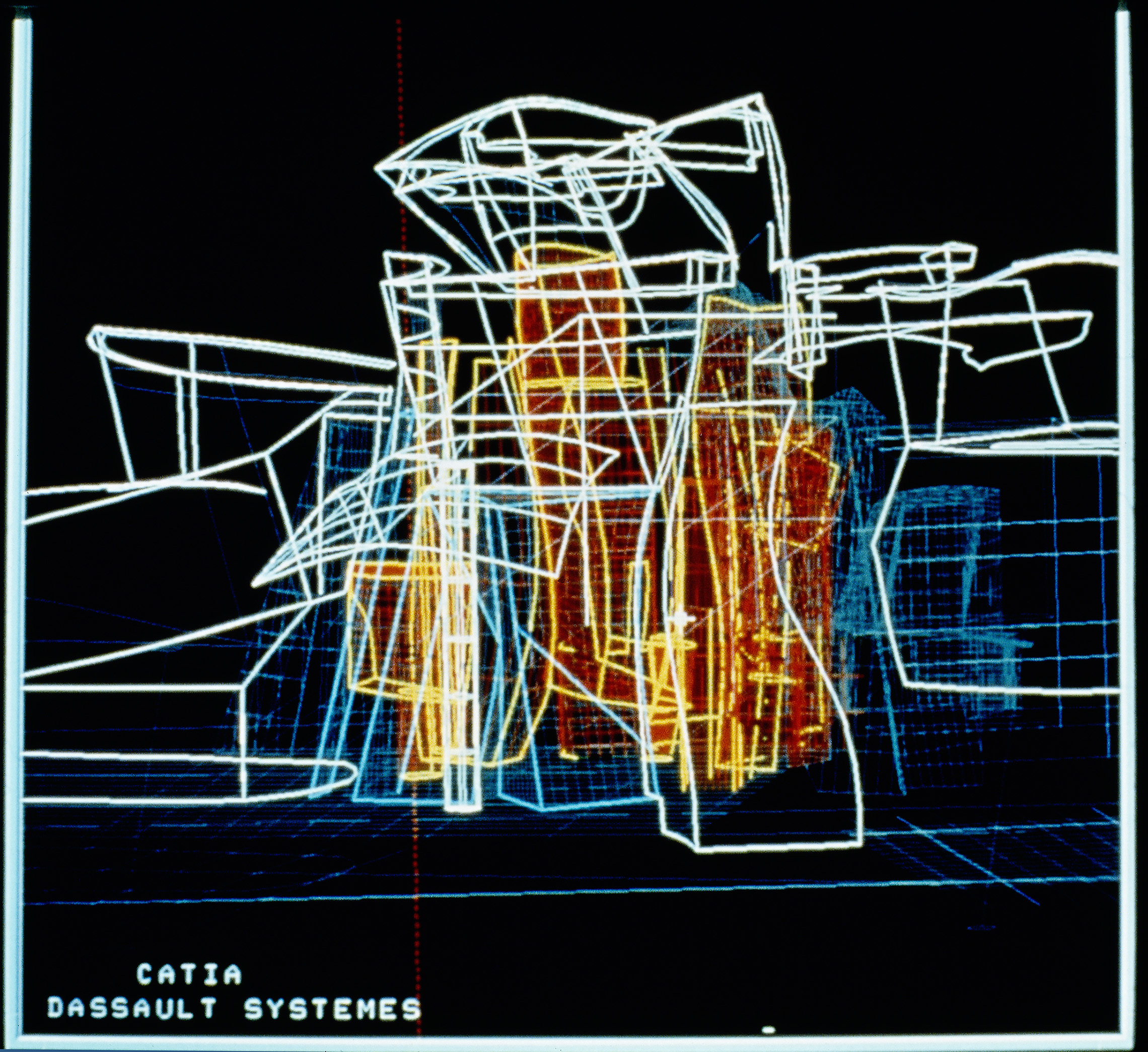

So the next thing I did was I did the show at Walker. I cut off the tail. I cut off the head. I got rid of the eyes and everything, made it as abstract as I could, and it still worked. You still felt a movement. So then I was able to take it into buildings. And that’s the history of that. And the only way I could build it — I couldn’t build it, because you couldn’t do it with descriptive geometry. The first attempts at it were kind of awkward and that was at Vitra. But through IBM they took me to Dassault, people that build airplanes in France, and their software, and I met with them in this office sitting here. We formed a kind of partnership and started working on using their software to define these buildings so they could be built. And Bilbao was the second building we tried it on. The first one was in Spain, this big fish sculpture where we were able to define multiple compound curves and build them.

Is it true that this software was originally developed for aeronautics?

Frank Gehry: The software was developed for airplanes.

I didn’t know it could be done inexpensively. I thought, “This isn’t going to be slam dunk.” We tried it on Bilbao and we trained the subcontractors. I sent people over to Spain and they spent time with the subs. And Bilbao is — they’re the greatest people. They’re willing to do things and make things. If they believe in it, they’ll – click! — if you’re not trying to pull the wool over their eyes. If you’re straight about what you’re doing, it was… So they became complicit in — and we had six steel companies bidding on the steel structure and there were no two pieces of steel in the steel structure that were the same. The bids came in one percent spread. That means the documents they were bidding on were tight, because everybody got the same answer. And they were 18 percent under budget. Now normally, if you get a few bidders they’ll be within six, five percent, four percent, and one of them is under. You won’t take that because you know they did something wrong. When you have six bidders, one percent spread, and all of them are 18 percent under, you can pick anyone you want, which is what we did. And they lived up to it. So that was nirvana. That was eureka, the eureka moment, Archimedes.

I went to Bilbao. I meet the people. They take me with Tom to the site. I look at it, think about it. We go to dinner. I felt very negative about the site, and I didn’t know how to express it or should I express it or should I say it. Should I talk to Tom about it first? And I delayed it, and anyway, I found myself at dinner sitting next to Tom [Krens] and having some drinks and everybody was happy and clink, clink, clink. And they asked me, “Mr. Gehry, what do you think of the site?” And I said without a blink, “It’s the wrong site.” I said, “The reason it’s the wrong site is that the wall — the 19th century wall which fits into the neighborhood perfectly— in order to build a museum like you want, you’d have to tear it down, and that would destroy the continuity of the neighborhood. I think it’s a beautiful relic. You shouldn’t tear it down. You can find other uses for that site that are more communal with that wall, can work with it.” And I was sitting there as I was talking, thinking when is he going to kick me, and he never did. So it went over like a clunk, right? There was this sort of clunk. Gehry came in. Clunk. But they were nice. They took us up on the hill overlooking the city. We had a few more drinks. Everybody was sort of, “So okay, if you don’t like that site, where would you put it?” By then I had a pretty good feeling from Patxaran and whatever they poured down my throat. I said, “I saw this bridge, and I saw this site with the brick factory and it looked derelict.” I don’t know what got in me. I said, “There.” And I don’t usually do things like that. In another circumstance I would have taken more time and said, “Let’s study this one, let’s study this one.” I brazenly said, “There.”

Right at the bend, right by the bridge. And you could see from the hill looking down that there was a straight-line view to City Hall across the river. I don’t know how much of this I really was aware of when I said it. And they said, “Well, that site can be acquired. It’s a derelict factory and the city would have to try to buy it. It’s probably expensive.” You know, they made up all these excuses. And Krens supported me and said, “If we could do that one, that’s one of the best sites.” And he said that he had been running along there in the mornings and picked that site as well. And apparently the people that he ran with said, “Yes, he did.” So he wasn’t making it up.

Did you already have an image in your mind of what you wanted Bilbao to be?

Frank Gehry: I did not. Because I had been talking to Tom I knew that he had his eyes on a [Dan] Flavin piece that was 400 feet long that Panza owned. I saw it in action at Count Panza’s villa or wherever he had it. When you turned it on, the lights went on and it was like static. It was like static. It was like gunfire. It went tick-tick-tick and went on for about ten minutes as it lit up across the room. It was quite beautiful.

Dan Flavin wasn’t really known for kinetic work. His stuff was beautiful but mostly it was fixed. It was about perception, perceptual relationships. And this was like a gunfire and lights. It was quite beautiful. And so that meant we had to have a 400-foot-long something. So that’s why that big long building. Tom talked to me about — I think he was able to talk to everybody, so he had a meeting with all the contestants and told us what he was dreaming of and thinking about. In my case I think they were different. He tailored it to what he thought each person was doing. In my case he said that if I want the galleries to be more sculptural, less rectilinear and traditional, that he would support that for living artists. He said, for the artists who are no longer with us, “I would like you to think of a more traditional gallery. But they don’t have to look like everyone else. You can turn them into something that you can do with them.” So that’s the plan of it. I brought to it the inclusiveness with the city so that as you walk from gallery to gallery, you’re always looking out at the city. And when you get to the center, you’re like in a space that’s part of the city. And that’s because of going to the Met so many times and being sort of claustrophobic and spending four hours going from gallery to gallery with no relief. The work was incredible. I came out drenched. I didn’t want to go to sleep. It was hard to. So I felt like in Bilbao that there is some visual virtue in the city, the hills around the bridge, and I assumed that they would clean it all up eventually, which they did. And it would be a big asset for the viewing of art. So that’s what led to the building.

People talk about the Bilbao effect. The name of Bilbao is now synonymous with your building.

Frank Gehry: They asked for that.

I had my first official meeting with the city when we were selected. They asked me if I could do the equivalent of the Sydney Opera House because they said — this was the Minister of Commerce, Jon Azúa, who’s still there — they needed this to be a generator, a commercial generator to bring people. What do you say to that? You say, “I’ll do my best, but it’s not a slam dunk. I don’t know if I can do it. I haven’t done it before but maybe.” When the building was being built, the city was skeptical, and there was one article in the paper, “Kill the American Architect.” That made me nervous. The separatist thing was going on and they didn’t like the idea of somebody coming in from Mars, and they didn’t understand what I was doing. This jumble of metal — ick! “What are you doing?” It’s only after they saw it, then everything clicked. I could live there for the rest of my life for free. If anybody sees me — I was in India somewhere in a plaza and some lady saw me. There was a group of tourists from Bilbao. I didn’t know they were over there. And she saw me, and she said, “Gehry, Gehry!” And they all came running and I was like the Pied Piper. I think it — obviously it worked. And I’m happy it worked. I don’t know why it worked. It’s a magic trick, I think. I did my best and that’s what came out. Since it’s opened, it’s earned close to four billion euros for a city, which changed the politics, it changed — there’s no more separatist. Whatever is left is very insignificant now. There’s a big smile on the community. The building brings in people.

The shows are uneven, but they’ve gotten better. Tom is no longer director. So Juan Ignacio kind of took over and he’s not an art guy, but he’s a quick learner and he’s very respectful of me and the art. So they’re all family now. On my 85th birthday Berta, my wife, wanted to do something for me. I said, “You know, I’d love to go to Bilbao and spend three or four days with the half a dozen friends that we’re close to and just hang out with them.” So I called Juan Ignacio. I said, “Do you think we could do something really quiet?” “Oh, yes. Don’t worry about it.” Guess what he did. A 250 sit-down dinner! Daniel Barenboim came from Berlin and played the piano for me, and they had people on television like Norman Foster and Herzog and Claes Oldenburg. So I feel loved there.

There’s been kind of a Bilbao effect in downtown Los Angeles with Disney Hall that I don’t think anyone could have anticipated. Weren’t there years when you didn’t think it would ever be built?

When you do a public building that has a board and people on it, there’s always somebody on the board that’s a builder that knows how to do everything better than the architect. So you have to go through all of that. I mean when I first showed the model, they brought a contractor who was the biggest contractor in L.A., and I finished my presentation and the board clapped. They loved the drawings and everything. They turned to him and said, “What do you think?” And he said, in my office with me present, “It’s beautiful but it can’t be built.” Well, it’s there and he’s not.

I think you got to come with reality. You know, when you’re thinking like this, when you’re having — you got to make sure it’s right and it can be built. You got to make sure it’s budget conscious. I mean nobody knows this about Disney Hall, it cost $207 million. Period. That was the budget and we made it. When they talk about it, they add all the other costs that they screwed up in there over the years that it was mismanaged by people that the Philharmonic trusted. So, but the real budget was 207. And so I’m very budget conscious. That means a lot to me, to be able to look a client straight in the face and say, “Here’s what you asked me for. Here’s the money you told me you had. And here’s what it looks like.” Now in the period of design, they can add to it, I mean, or subtract and say, “No, I want it higher,” and that costs 20 million more, and you say, “Okay. Are you willing to do that?” That’s what happened in Australia. The building had X budget. I think it was $80 million. And it was a box. And I was getting excited about making it, and they said they needed a height, a high rater, and blah, blah, blah. And so that was a 20 million extra. We made models, showed it. They showed it to a donor. He gave them 30 million extra to build it that way and it’s built. That satisfied the needs of the client, but at least it was done respectfully in the process, and I really rely on that process so that we go through it, come out the other end and we’re still friends. And 98 percent of my clients and I are still friends. We talk to each other and trust each other. And so Bilbao was right on budget.

You can do it. It can be done if the budgets are real, and the expectations are set, real, and they’re explained along the way, that if you want a marble kitchen top, that costs $50 more. Well, okay, it’s your choice, but you don’t have to do it. I don’t have a gun at your back to say you got to have that marble. I don’t know how many architects practice like I do. I’ve always assumed they did, but the clients tell me they don’t, that we’re kind of unique that way.